Abstract

This paper argues that semelfactive and degree achievement verbs are morphosyntactically distinct, despite the fact that the morphemes they are made of are often syncretic even in languages with synthetic verb morphology like Czech or Polish. We use the mechanisms of Nanosyntax, a theory of the architecture of grammar in which the lexicon stores entire syntactic subtrees, to show that there is a structural containment between semelfactives and degree achievements such that semelfactives include more syntactic structure than degree achievements. In this respect, the relative structure of these two verb classes contributes to Bobaljik’s (2012) general claim that syncretism anchors structural containment as well as to the ongoing discussion about the form of spell out in syntax. The resulting picture supports the view whereby the semantics of lexical items is determined by their fine-grained internal syntax.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction and synopsis

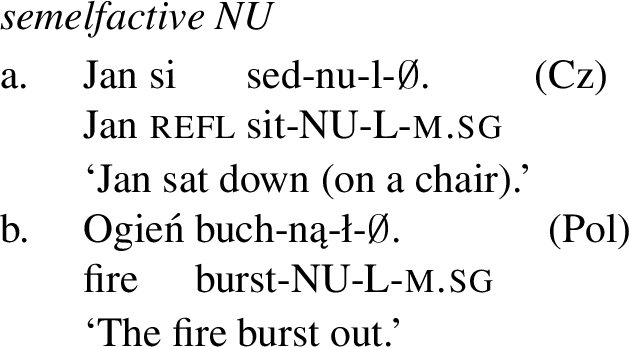

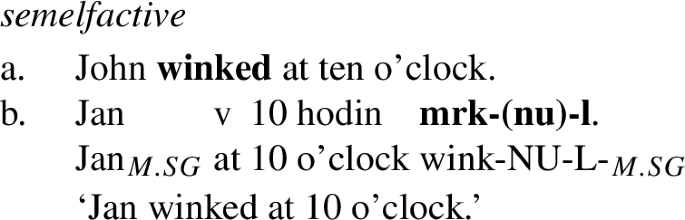

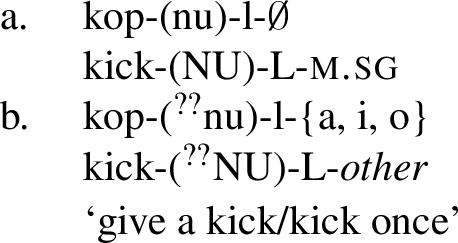

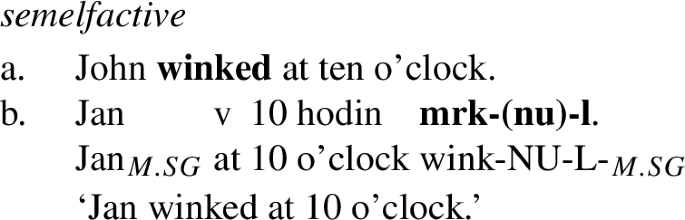

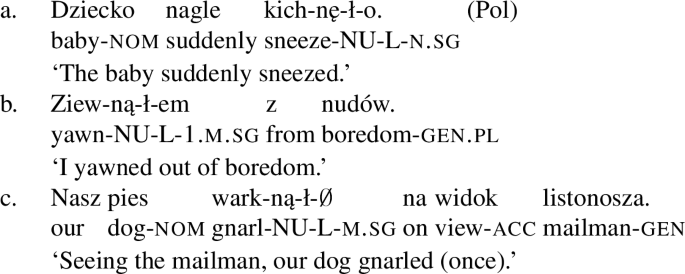

Languages like English do not exhibit a morphological distinction between verb stems that belong to different structural or aspectual classes. That is, a stative transitive verb love and an activity intransitive verb walk both have monomorphemic stems and their argument structure properties cannot be predicted on the basis of their morphology. Moreover, verbs of different aspectual classes are sometimes homonymous with each other, for example, a semelfactive wink denotes a single-stage event in a sentence John winked at ten o’clock and is homonymous with an activity as in John winked furiously for several minutes till he got our attention. On the other hand, languages which exhibit a considerable degree of morphological compositionality in the formation of verb stems, like for instance Slavic languages, may not show a morphological distinction between two or more aspectual verb classes, either. This is the case with the Czech suffix NU, as well as its equivalent in Polish and some other Slavic languages, which creates either semelfactives in (1) or degree achievements in (2).

-

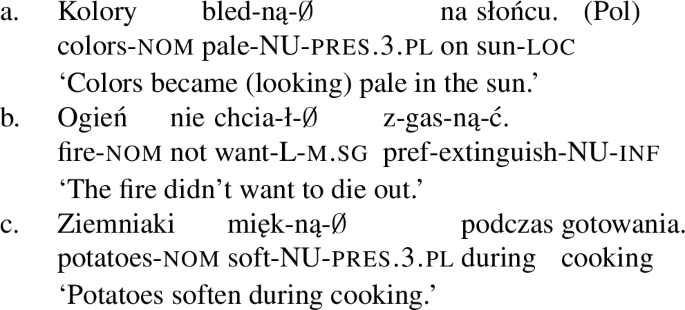

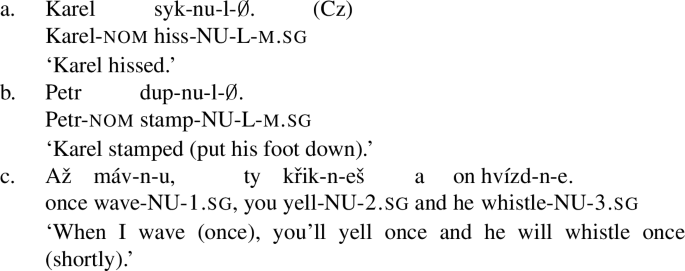

(1)

-

(2)

Despite the fact that semelfactives and degree achievements are morphologically indistinguishable, we argue that they are structurally different. Namely, there is a syntactic containment relation between these two types of stems such that semelfactives are structurally bigger than degree achievements.

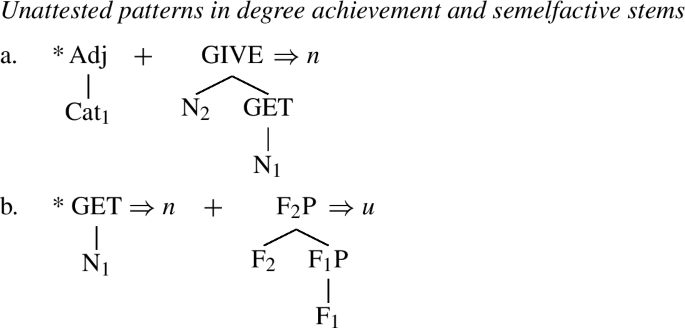

We argue for the existence of structural inclusion of degree achievement structure inside the semelfactive syntactic structure on the basis of four new empirical discoveries about the NU-stems together with three motivated assumptions about syntactic containment.

-

(3)

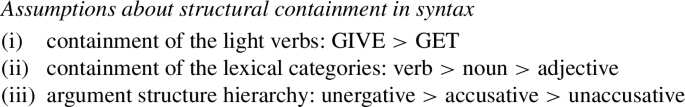

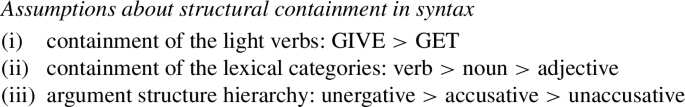

These empirical findings are going to be coupled with the following assumptions about the following containment relations in syntax (where > stands for inclusion based on dominance):

-

(4)

The paper proceeds as follows. Before we discuss the properties of the Slavic NU morpheme and the way it provides the insight into the syntactic structure of semelfactives and degree achievements, we outline the mechanisms of Nanosyntax in Sect. 2. Nanosyntax is a theory of the syntax-lexicon interface whose major premise is that the lexicon stores entire syntactic subtrees and that spell out targets subconstituents of fine-grained syntactic representations rather than terminal nodes. The way Nanosyntax explains syncretic morphology is going to be essential in the analysis of NU.

In Sect. 3 we discuss the properties of NU in the context of other Slavic theme vowels. We show that degree achievement stems result from the merger of NU with adjectival roots and semelfactive stems result from the merger of NU with nominal roots. We also identify challenges in treating the NU sequence as a theme vowel and, instead, we propose that NU is not a singleton morpheme but two separate morphemes of which only U is a thematic suffix and N spells out the light verb.

Section 4 puts forward the light verb theory of the N morpheme, where it is argued that N incorporates the sequence ‘GIVE > GET’. We then use the containment theory of lexical categories, whereby nouns and verbs are bigger than adjectives to observe that semelfactive stems are syntactically bigger than degree achievement stems in two ways: they include bigger roots and the light verb GIVE present in the structure of semelfactives is bigger than the light verb GET in degree achievements.

In Sect. 5, we discuss the other morpheme of the split NU sequence, the thematic suffix U, which is responsible for the argument structure properties of verb stems. The discussion of the properties of the U-theme allows us to observe a third difference between the two aspectual classes of the NU-stems: semelfactive stems spell out the argument structure of a larger size than degree achievements do. This explains why Czech and Polish degree achievement verbs based on NU-stems are exclusively unaccusative, while semelfactive verbs are either transitive/accusative or unergative.

In Sect. 6 we show how the selectional restrictions between lexical categories of roots, the size of the light verb N, and the size of the U-theme become spelled out together into an attested morpheme order.

A brief Sect. 7 depicts the relations between the three zones of functional sequence discussed in the previous sections.

Section 8 is a short excursus on a thematic suffix EJ, which can also form degree achievement, but not semelfactive, verb stems.

Before we proceed to discuss the syntax of NU—a morpheme which builds both semelfactive and degree achievement stems in Czech and Polish—in a greater detail, consider first how syncretism has been used to explain the morpheme–phrasal syntax connection in Nanosyntax and its consequences to structure and interpretation of grammatical representations.

2 Nanosyntax: What syncretism teaches us about representation and lexicalization of syntactic structures

Nanosyntax is a new and developing theory of the syntax–lexicon interface, whereby the lexicon stores entire syntactic subtrees. The major tenet of Nanosyntax stems from the observation that terminal nodes of syntactic representations are smaller than morphemes, that is, syntactic structures can be submorphemic (Starke 2006, 2009, 2014). A scenario in which morphemes often relate to more than one, and often several, syntactic projections emerges from the expanding work on the structuralization of lexical semantics (see especially Ramchand 2008, among many others) and is consonant with what has often been called the strong cartographic thesis, namely that each grammatical feature heads its own syntactic projection (see, for instance, Cinque and Rizzi 2008:50).

The major advantage of Nanosyntax is the way it explains syncretism and morphosyntactic derivation of syncretic forms. The explanation based on mechanisms of spell out offered by this approach leads to the view that syncretism anchors the structural containment of grammatical representations, the conclusion reached also in Bobaljik (2012) on independent grounds.Footnote 1

2.1 Linear contiguity as structural containment

On the basis of a wide cross-linguistic study into suppletive forms of adjectival comparative and superlative morphology, Bobaljik (2012) argues that adjectival root forms are morphosyntactically contained in the structure of comparative forms, which are in turn contained in the structure of superlative forms, as in (5).

-

(5)

[[[ root ] comparative ] superlative ]

This claim is based on the observation that in nested structures (paradigms), a more complex structure and a less complex structure are not spelled out as an exponent A, if structures that are in between them in terms of complexity are spelled out as an exponent B (‘the *ABA’). In the domain of comparative and superlative suppletive morphology, this constraint can be illustrated by the following patterns.

-

(6)

root

comp

superl

pattern

English

smart

smart-er

smart-est

AAA

English

good

bett-er

be-st

ABB

Polish

dobry

lep-szy

naj-lep-szy

ABB

Latin

bon-us

mel-ior

opt-imus

ABC

Welsh

da

gwell

gor-au

ABC

unattested

*ABA

Bobaljik’s conclusion that superlatives morphologically include comparatives entails a bigger picture: elements that form a paradigm are in a containment relation.

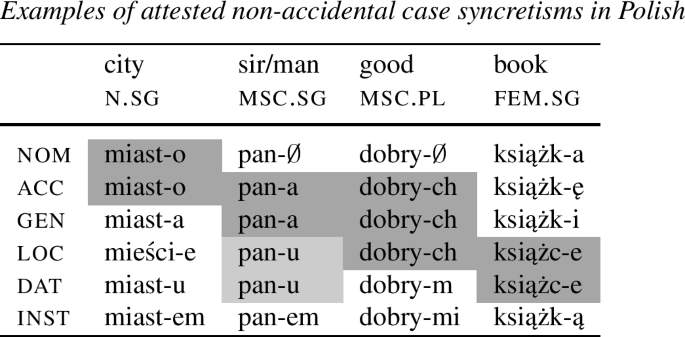

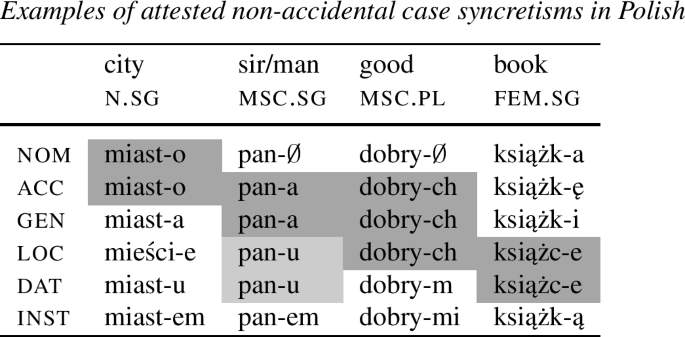

The same view emerges from what we observe in the domain of case in Caha’s (2009, 2013) work, which shows that case involves a containment of universally ordered privative features Kn merged on top of the NP, as in (7), and individual cases such as ‘accusative’ or ‘dative’ result as a spell out of cumulatively ordered features Kn, as in (8).Footnote 2

-

(7)

-

(8)

nom ⇔ [ K1]

gen ⇔ [ K3 [ K2 [ K1]]]

loc ⇔ [ K4 [ K3 [ K2 [ K1]]]]

dat ⇔ [ K5 [ K4 [ K3 [ K2 [ K1]]]]]

inst ⇔ [ K6 [ K5 [ K4 [ K3 [ K2 [ K1]]]]]]

Such a representation explains the *ABA found in case paradigms, with the difference that they comprise more paradigmatic cells than comparative morphology, as in the examples from Polish, which morphologically distinguishes 6 cases.

-

(9)

Adopting the containment theory of case, the *ABA can be explained structurally in the following way: syncretic spans are restricted only to contiguous regions of (7).Footnote 3

2.2 Spell-out

The restriction of syncretic spans to adjacent cells follows from the two major claims of Nanosyntax, namely that (i) lexical insertion targets phrasal nodes and (ii) it is regulated by the Superset Principle.

-

(10)

The Superset Principle

A phonological exponent of a lexical item is inserted into a syntactic node if its lexical entry has a (sub-)constituent which matches that node. Where several items meet the conditions for insertion, the item containing fewer features unspecified in the node must be chosen (Starke 2009).

This principle can be broken into two ingredients: the Superset clause and the Elsewhere Condition. The Superset clause explains the one-to-many relation between exponence and meaning, since it allows an exponent of a single lexical item to realize more than one syntactic representation. The Elsewhere Condition makes sure that if there is more than one possible lexical item to match a syntactic representation, it is the most specific item which wins the competition for insertion.

For example, there is a lexical item made of three features A, B, C, whose phonological exponent is α as in (11).

-

(11)

Lexical entry:

-

(12)

Syntactic representations:

-

a.

-

b.

-

c.

-

a.

According to the Superset statement of (10), the representations in (12a) and (12b) are both spelled out as α since they constitute a superset, in (12b), and proper subset, in (12a), of α. In other words, the syntactic structure in (12a) is spelled out as α just like (12b) is, due to the fact that it is contained in the lexical entry of α.

In contrast, α is not inserted into (12c). This structure does not match the lexical entry of (11). As a result, only (12a) and (12b) come out as syncretic. (12c) can only become lexicalized if there is another lexical item β, such that it includes also (at least) feature D in its specification, like in (13).

-

(13)

Lexical entry:

While the presence of a lexical item β in a language allows all the syntactic representations listed in (12) to be spelled out, we now face a problem of competition for lexical insertion: (12b) can spell out both as (a perfect constituent of) α and as (a proper subconstituent of) β. This competition is resolved by the Elsewhere clause of (10), a condition well-established in the work on morpho-phonology since at least Kiparsky (1973). The Elsewhere Condition makes sure that (12b) spells out as α, which is a more specific match than β.Footnote 4

Note that once feature D is merged with the existing structure CBA, the previous spell out of CBA as α is superseded by β, which lexicalizes the bigger tree.

-

(14)

This principle is called Cyclic Override, as an attempt to spell out takes place after each merge. The result is that a lexical entry matching a bigger tree will always override the smaller matches.

With these basic lexicalization principles in place, let us consider how a case paradigm of pan ‘man, sir’ in (9) with two syncretic pairs, acc=gen-a and loc=dat-u, becomes spelled out. Given (7), the complete set of the case entires is as follows.

-

(15)

Lexical entries for cases for pan ‘man, sir’(msc.sg)

-

a.

/∅/ ⇔ [ K1]

-

b.

/a/ ⇔ [ K3 [ K2 [ K1]]]

-

c.

/u/ ⇔ [ K5 [ K4 [ K3 [ K2 [ K1]]]]]

-

d.

/em/ ⇔ [ K6 [ K5 [ K4 [ K3 [ K2 [ K1]]]]]]

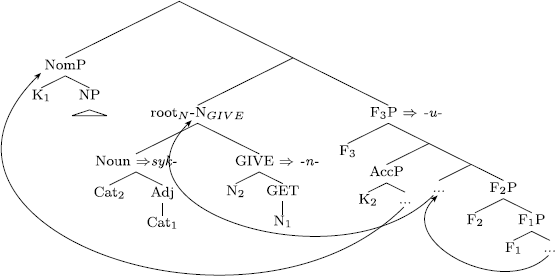

While the sets of features to the right of the exponents above correspond to the cases in the paradigm of pan, these sets do not form constituents of the case fseq in (7) and, hence, cannot be spelled out. In order to facilitate spell out, (7) must be changed into a representation with the relevant K-features in lexicalizable constituents.Footnote 5 This is achieved by the so-called spell out driven movement, which takes the form of successive-cyclic movement of the NP in (16), to the effect that phrasal constituents such as NomP, AccP, etc. come out as suffixes on the NP.

-

(16)

Spell-out driven NP-movement

Two final observations are to be made about this derivation. The first is that we have naturally achieved a scenario in which the entire phrasal constituents rather than terminal nodes get spelled out.Footnote 6 In such a system, each application of Merge is followed by lexical access from PF, which consists of exponents available to insertion at a given syntactic node, which we see in (16) where the size of the case suffix gets bigger and bigger with each merger of the NP upward in the case fseq.Footnote 7

The second is that what moves in a spell-out driven movement in the case fseq is only (and always) a constituent which contains the head noun, which is in concert with the restrictive theory of NP-internal movements of Cinque (2005).

2.3 Peeling

Apart from a successive-cyclic (spec-to-spec) movement in (16), movement can involve stranding, in which case only the bottom layers of an fseq are extracted, as in the so-called peeling derivation outlined in (17).

-

(17)

It is important to consider peeling from the perspective of the fate of the fseq layers stranded by extraction. That is, if the syntactic tree (18a) with A at the bottom is lexicalized as α (as it matches the entry (11)), then the constituent in (18b) with C at the bottom derived by extraction clearly is not (as it does not constitute a proper subconstituent of (11)).

-

(18)

Such a derivational scenario is not abstract—Caha (2009)/(2013) argues that in the domain of case, peeling movement changes structurally bigger cases into smaller cases, e.g. K2P into K1P. This is exhibited by the fact that the higher the position of the NP in the clause is, the smaller the case in the hierarchy in (7) this NP bears.Footnote 8 For example, in (19), the NP base-generated together with case projections on top is attracted by a licensing head in the NP-external domain.

-

(19)

The movement of K2P is triggered by checking its features against the head Y. In turn, the movement of K1P is triggered by checking its features against the higher head X, which is subextracted from K2P.Footnote 9

The aspect of peeling that is going to be most relevant in the discussion of semelfactives and degree achievements is what happens to case layers stranded by extraction. That is, if (20a) with K1 at the bottom spells out as accusative case morphology, then what does (20b) spell out as?

-

(20)

In Caha (2009) and Taraldsen Medová and Wiland (2018), case peels are argued to constitute parts of lexical entires of other morphemes. In what follows, we will extend this reasoning to argue specifically that peels stranded by NomP-extraction as in (20b) are spelled out as part of unergative verb stems in Czech and Polish. What is even more essential, however, is that peeling is a general property of Nanosyntax and is not limited to the domain of case. We will argue that it also applies in the domain of verbs.

Since Czech and Polish semelfactive and degree achievement stems are derived by the syncretic morpheme NU, we will apply the same logic and methodology as just outlined in the analysis of their syntactic structure. The resulting picture is going to be consonant with the view that syncretism anchors structural containment of morphosyntactic representations.

3 Slavic themes and the problem of the NU morpheme

Most Slavic verbs have a clear morphological make-up. Verbs with the NU morpheme stand out in two ways: they form two different aspectual classes (semelfactives and degree achievements) and they differ morpho-phonologically from the rest of the verbs. Before we discuss the properties of the verbs with the NU morpheme and observe what they indicate, let us first review the structure of the Slavic verb.

3.1 Verbs and theme vowels

3.1.1 Verb morphology

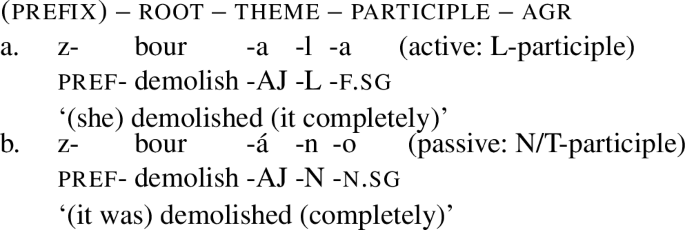

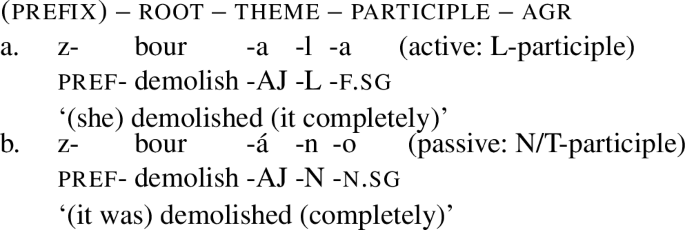

The format of a Slavic verb is to a considerable degree templatic (cf. Jakobson 1948; Laskowski 1975; Townsend and Janda 1996), as shown in the example from Czech in (21).Footnote 10

-

(21)

The root is optionally preceded by a prefix that introduces various aspectual and aktionsart properties, it is followed by a thematic suffix (the so-called theme vowel), which contributes to the argument structure properties of the verb stem, as we illustrate it below.

The theme is followed by a participial suffix: either active (non-present) L or passive N/T, as in (21a) and (21b), respectively. The ending (marked as ‘AGR’ in (21)) indicates subject agreement in gender and number. Neither the form of the participle nor the AGR suffix contribute to the aspectual properties of verb stems (i.e., a semelfactive verb stem remains semelfactive irrespective of whether it is suffixed with an active or passive participle). By and large, we are not concerned with prefixes, participles or agreement in this work and we concentrate exclusively on the verb stem, that is a combination of the root with the thematic suffix.

There are six themes in Czech and Polish: E, AJ, OVA, I, EJ, and NU. There is a long tradition in Slavic phonology of analyzing theme vowels as cyclic morphemes, that is, morphemes subject to phonological rules sensitive to morpheme boundary. In other words, there is abundant evidence from the work on Slavic phonology for the existence of a morphological boundary before and after a theme vowel, as indicated in (21) (see Rubach 1984, among many others).

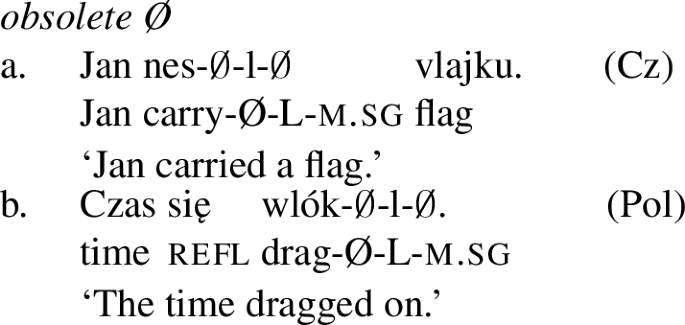

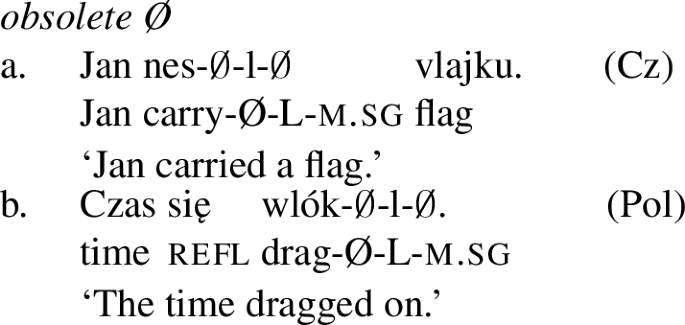

The morphemes whose phonological exponents are theme vowels encode the verbal argument structure together with the root they merge with. This picture, however, is not fully clear since the root–theme combination has been a location for various phonological changes throughout the historical development of Slavic languages, an example of which is the existence of an obscure theme vowel whose phonetic exponent is Ø,Footnote 11 as in (22).

-

(22)

We tend to find the Ø-theme in verb stems belonging to different verb classes; there are activity verbs as in (22a), reflexive anticausative verbs like in (22b) and also some unaccusatives, e.g. Polish umrzeć ‘die’ or paść ‘fall’.

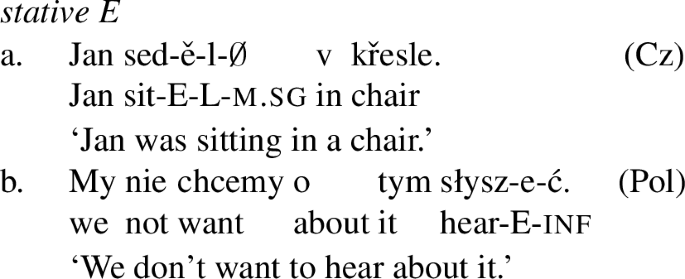

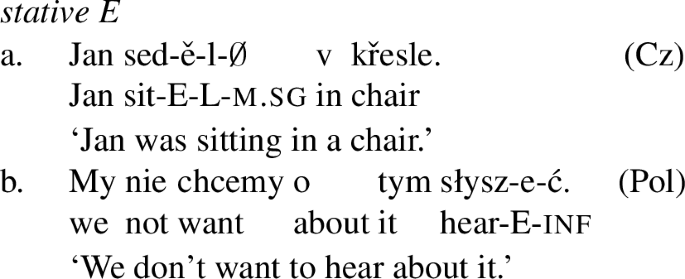

Furthermore, there are relatively infrequent verbs with the theme E. This theme builds stative verbs and a group of verbs related to perception or production of sounds (e.g. Polish jęcz-e-ć ‘moan’):

-

(23)

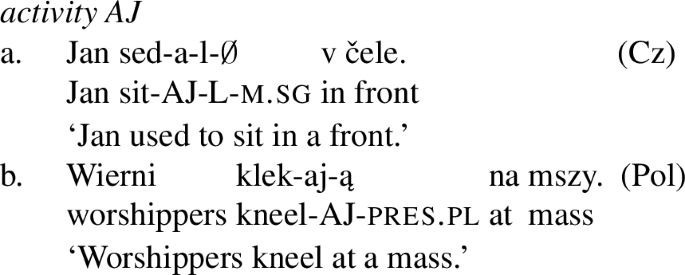

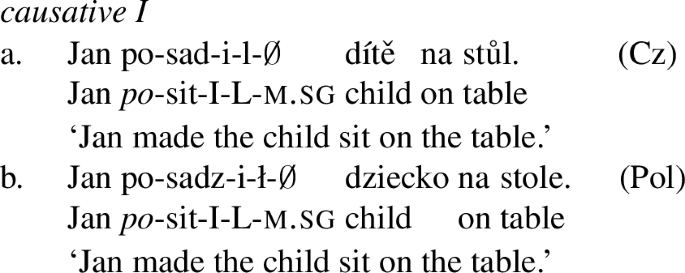

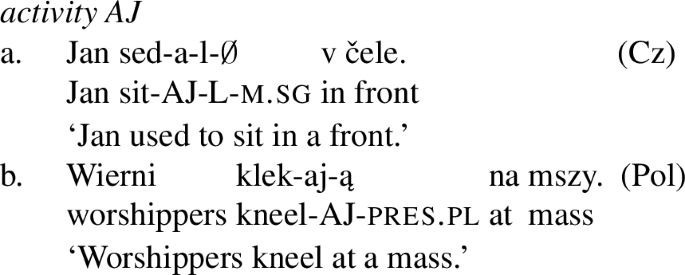

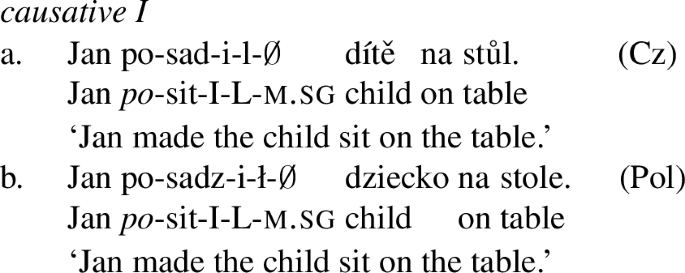

In turn, AJ, OVA and I themes derive activity verbs. In this group, the I theme is a typical ingredient of causative verbs (cf. ‘make X do Y’).Footnote 12

-

(24)

-

(25)

-

(26)

With an exception of EJ-stems, which we go back to later, we leave other verb stems out in our discussion and instead we focus on degree achievement and semelfactive stems.

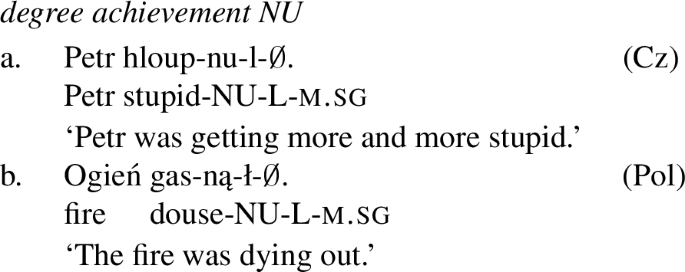

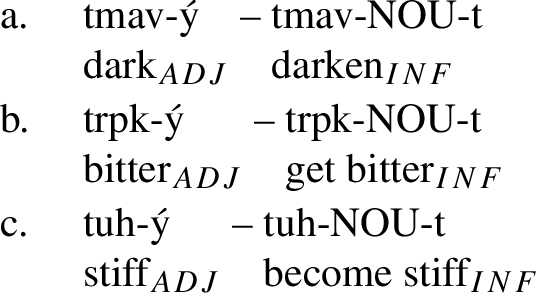

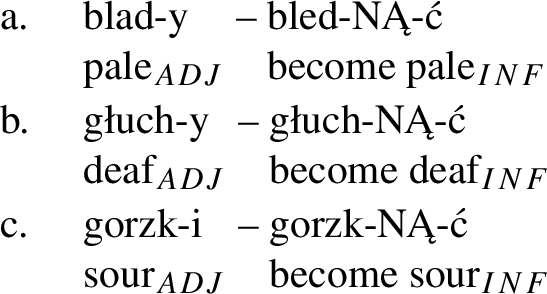

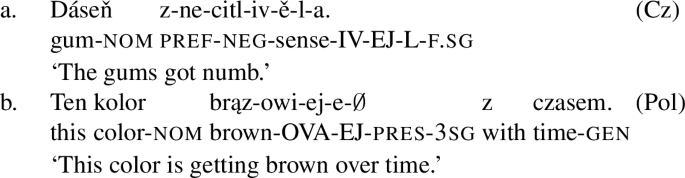

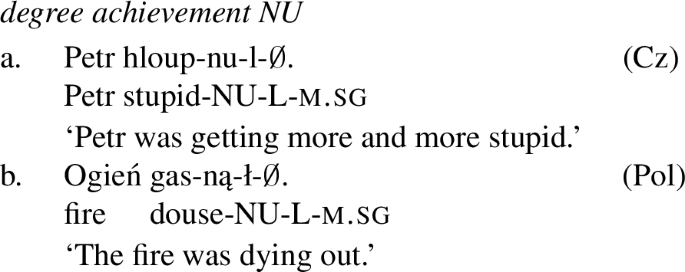

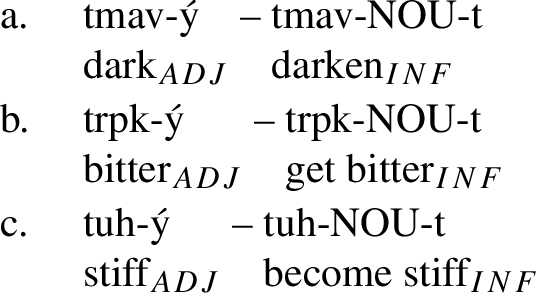

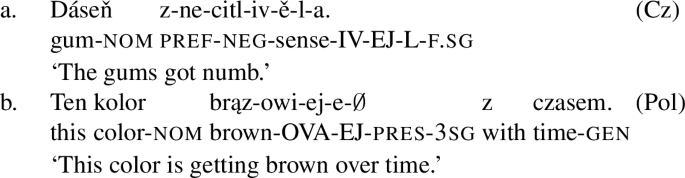

Degree achievement stems are derived in Czech and Polish either by the theme EJ, as in (27),Footnote 13 or NU, as in (28). The term ‘degree achievement’ comes from Dowty (1979) and like Hay et al. (1999) and many others, we will keep using it for expository purposes (despite the fact that we, just like many others, do not share the intuition that such verbs actually denote achievements).

-

(27)

-

(28)

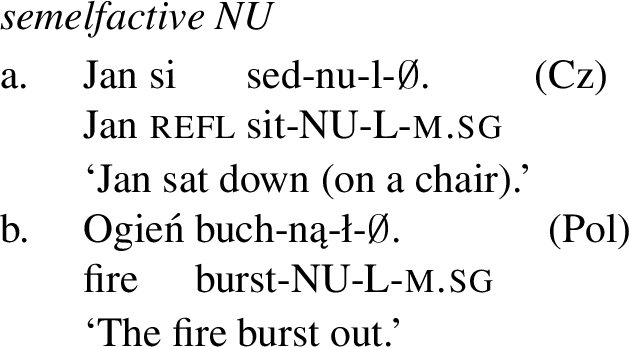

The Czech and Polish degree achievements are best rendered by the English gloss ‘get’ or ‘become,’ cf. ‘get/become grey, rusty, stupid,’ to indicate the meaning of examples (27) and (28). Whether a verb selects the theme EJ or NU is a question we leave unanswered for the most part of what follows. Nevertheless, quite clearly, in contemporary Czech and Polish, the choice is lexicalized. In other words, the degree achievement stems are formed by either NU or EJ, never both.Footnote 14 The theme NU can also—when merged with roots other than those which form degree achievements—create semelfactives, roughly defined as one-time events. In the case of these Slavic verbs, the native speakers instinctively also add that they denote events very short in duration.

-

(29)

In the rest of this section, we show that the theme NU is rather specific among the Slavic themes: not only does it create two aspectually distinct types of verbs, it is also the only Slavic theme that has a consonant in the onset. Before we go on to focus on the morphosyntax and semantics of NU, let us first briefly mention a phonological rule of Glide Truncation, which explains why certain theme vowels in inflected verb forms are sometimes difficult to recognize.

3.1.2 Verb phonology: Glide Truncation

The themes AJ and EJ surface as /a/ and /e/, respectively, whenever they are followed by a non-present active L- or passive N- or T-participle suffix, exactly as we observe it in (21). The glide becomes deleted by a phonological rule of Glide Truncation, whereby glides are deleted before a consonant in Slavic (Jakobson 1948):

-

(30)

j, w ⇒ ∅ / _ C0

This cyclic rule deletes morpheme final glides in AJ and EJ themes also in other contexts, including a boundary with the infinitival suffix -t in Czech or -ć in Polish. This is observed in infinitives like, for instance, in Polish łysi-e-ć ‘lose hair’ (not *łysi-ej-ć). The underlying shape of the theme vowel is preserved in surface forms of non-past tense inflection, for instance 1.plłysi-ej-e-my or in the imperative łysi-ej. The truncation rule operates on cyclic morphemes (by and large, the suffixes) and does not apply to non-cyclic domains, which results in glides being preserved at the prefix-stem boundaries, as in the Polish adjective naj-większy ‘biggest’ (not *na-większy).

3.2 Properties of NU

The combination of a root and the NU-theme builds either semelfactive (in (31)) or degree achievement (in (32)) stems, never both, in the sense that it is never ambiguous between degree achievement and semelfactive.Footnote 15’Footnote 16

-

(31)

semelfactive stems

-

a.

kop-nou-t ‘kick once’ (Cz) kous-nou-t ‘bite exactly once’

couv-nou-t ‘go back one step’

-

b.

kop-ną-ć ‘kick once’ (Pol)

umk-ną-ć ‘escape once’

dotk-ną-ć ‘touch once’

-

a.

-

(32)

degree achievement stems

-

a.

mrz-nou-t ‘become frozen’Footnote 17 (Cz)

slep-nou-t ‘become blind’

bled-nou-t ‘become pale’

-

b.

marz-ną-ć ‘become frozen’ (Pol)

sch-ną-ć ‘become dry’

chud-ną-ć ‘become slim’

-

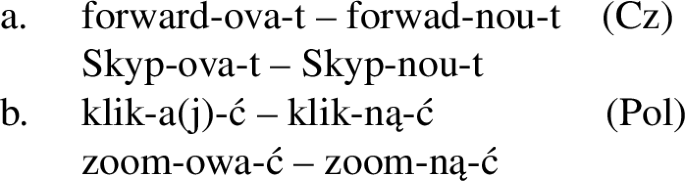

a.

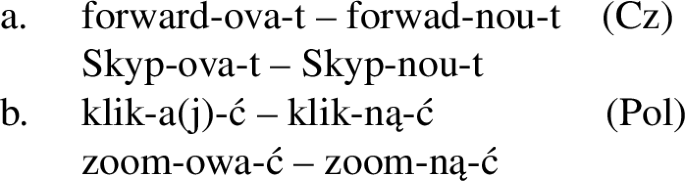

While the two readings are exclusive in both Czech and Polish, NU is productive only for semelfactives, not for degree achievement, which we see on the examples of borrowings:

-

(33)

In Czech, NU-based degree achievements and semelfactives have exactly the same morphological behavior: the allomorphs of the NU morpheme, -nou-, -nu-, and -n-, appear in exactly the same environments, like imperative forms of degree achievement bled-nou-t – bled-n-i! ‘get pale’ or semelfactive kop-nou-t – kop-n-i! ‘give a kick’ or, in the case of the -nu- allomorph, in past masculine gerunds forms like vy-bled-nu-v ‘having gotten pale’ or vy-kop-nu-v ‘having kicked’. It is perhaps worth mentioning that according to Caha and Scheer (2008), the infinitival allomorph -nou- surfaces as a result of templatic lengthening, a phonological process dependent on the morphosyntactic structure of Czech infinitives.

The phonological shape of the Polish equivalent of the Czech -nu- is - -. This exponent has been claimed to be either an underlying -non-, which undergoes the nasalization process involving a vowel followed by a nasal consonant in a coda (Gussmann 1980; Rubach 1984), or alternatively, a nasal diphthong consisting of a vowel and a nasal glide (Czaykowska-Higgins 1988). Throughout the paper, we refer to the thematic suffix which builds degree achievements and semelfactives as NU both for Czech and Polish.

-. This exponent has been claimed to be either an underlying -non-, which undergoes the nasalization process involving a vowel followed by a nasal consonant in a coda (Gussmann 1980; Rubach 1984), or alternatively, a nasal diphthong consisting of a vowel and a nasal glide (Czaykowska-Higgins 1988). Throughout the paper, we refer to the thematic suffix which builds degree achievements and semelfactives as NU both for Czech and Polish.

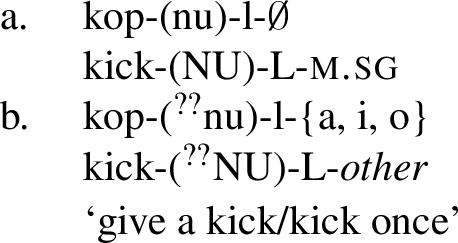

Another property of NU in both degree achievements and semelfactives is that it disappears in certain forms of participles (both in Czech and Polish). In L-participles (cf. (21a)), the NU tends to appear only in the masculine singular form, but in other singular and plural forms, it tends to disappear. There is a certain degree of variation among speakers of Czech and Polish with respect to which inflected forms retain or delete NU, as for instance in the following examples from Czech.

-

(34)

-

(35)

3.3 Degree achievement vs. semelfactive stems

The most telling difference between degree achievement and semelfactive stems with the NU-theme in both Czech and Polish is that degree achievement stems have adjectival roots while semelfactive stems have nominal roots.

3.3.1 Degree achievement roots are adjectival

Some examples of adjectival roots (which form adjectives when suffixed with an adjectival inflection -ý in Czech, as in (36), and -y/-i in Polish, as in (37)) in degree achievement stems are as follows:

-

(36)

-

(37)

The format of a degree achievement stem is, thus, ‘an adjectival root + NU.’Footnote 18

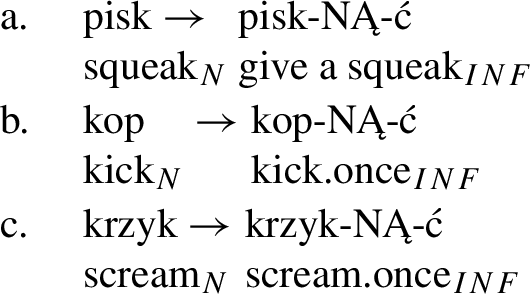

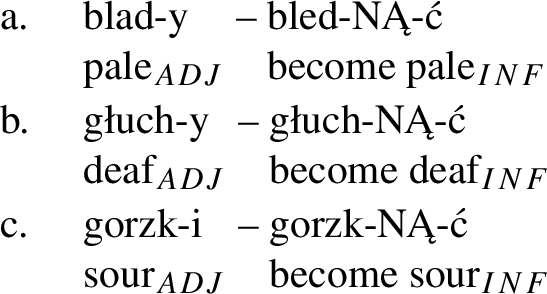

3.3.2 Semelfactive roots are nominal

The roots of semelfactive stems are nominal in both Czech and Polish (as in (38)–(39), respectively), rendering the format of a semelfactive stems as ‘a nominal root + NU’.

-

(38)

-

(39)

The picture of semelfactive stems comprising a nominal root and NU is rather clear except, perhaps, two observations.Footnote 19

First, the directionality of the noun—semelfactive stem relation is not always crystal clear, as nominal roots can also merge with certain other themes, as in (40) for instance (we return to this fact later).

-

(40)

Second, there are a few NU-stems that are clearly not semelfactives, but activities. Importantly, all these activity stems have verbal rather than nominal roots (in both Czech and Polish).

-

(41)

-

a.

ply-nou-t ‘flow, follow’ (Cz)

-

b.

vi-nou-t ‘wind, wrap’

-

c.

ž-nou-t ‘mow, cut’

-

d.

tisk-nou-t ‘print once/print’

-

a.

-

(42)

-

a.

ciąg-ną-ć ‘pull, drag’ (Pol)

-

b.

pło-ną-ć ‘burn’

-

c.

pach-ną-ć ‘smell nice’

-

d.

pły-ną-ć ‘swim’

-

a.

It is significant to note that the roots in (41)–(42) form verb stems only, that is, these roots will not form adjectival or nominal stems (except for nominalizations and deverbal nouns, the forms which are derived from the entire verb stem, not the bare root, as they contain the N part of the theme vowel, as in Polish ciąg-n-ik ‘tractor’ or s-pło-n-ka ‘combustible detonator’). This is also manifested by the fact that they merge with typically verbal prefixes such as za-, as in za-vinout ‘swaddle’, za-ciągnąć ‘pull onto’, or prze-płynąć lit. ‘manage to complete a certain distance swimming’, where an excessive prefix prze- can be added only to stems based on verbs. The situation in which the property of a stem is determined by the combination of a particular category of root and a morpheme it directly merges with is a scenario which challenges an often adopted hypothesis that roots are acategorial. We observe such a situation in (41)–(42), where a rather exceptional merger of typically verbal roots and NU results with the formation of activity stems. This adds up to the pattern in which the merger of NU with an adjectival root produces a degree achievement stem and its merger with a nominal root produces a semelfactive stem.Footnote 20

It is important to note at this point that there are also a few verbs with the NU theme that are neither degree achievement nor semelfactive—and which are still different from those listed in (41)–(42). Historically, these verbs belong to the NU conjugation because their roots end in n (or m, as for instance in vez-m-u ‘take.1.sg’). These verbs share the conjugation type with degree achievements and semelfactives but without having the degree achievement or semelfactive semantics. According to Šmilauer (1972:241), in contemporary Czech there is a rather odd-looking group of 7 roots (sometimes referred to as the začít ‘start’ type in traditional Czech grammatical description) whose present-stem forms look exactly as any NU-verb (e.g. za-č-n-u ‘start-1.sg’ is exactly as za-kop-n-u ‘stumble-1.sg’) whereas their past-stem forms lack the N-morpheme completely but in a way different from the disappearing NU in the past forms discussed in (34)–(35), namely za-č-a-l ‘start-m.sg’ vs.za-kop-(nu)-l ‘stumble-m.sg.’ Three of these verbs even have roots that end in m and even they were attracted to the black hole of the N-based conjugation introduced in Late Common Slavic (e.g. vez-m-u ‘take.1.sg.pres’ – vz-a-l ‘took-m.sg.past’ – vzí-t ‘take.inf’). The NU-lization of these verbs is still in progress, as shown by the colloquial version of the infinitive: instead of the expected začít ‘start-inf’ a new NU-based infinitive form zač-nou-t is occasionally used. Thus, it appears that the root ending in n is a reason for verbs that are not semantically degree achievement or semelfactive to still follow the NU conjugation paradigm.Footnote 21

3.4 NU is inexplicable as a theme vowel

We have seen that Czech and Polish theme ‘vowels’ include Ø, E, EJ, NU, AJ, OVA, and I. Given that Slavic roots are typically CVC-clusters, themes make sense as vowels which complement the CVCV pattern typical for Slavic phonology. In this respect, NU stands out as odd with a consonant in the onset (not to mention the fact that it is hard to call NU a ‘vowel,’ similarly to OVA).

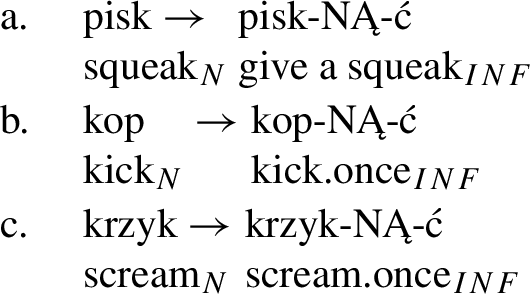

There are, however, morpho-semantic reasons which indicate that both Czech NU and its Polish equivalent NĄ are not themes but rather constitute sequences of two morphemes, whose exponents are /n/ and /u/ in Czech and /õ/ (spelled as -ą-) in Polish. The latter are the real theme vowels and N is a morpheme that lexicalizes the light verb which comprises the sequence ‘GIVE > GET’. In particular, we submit that the morpheme N in semelfactive stems spells out the GIVE layer, while in degree achievement stems N spells out the GET layer of the light verb. This is mirrored by the fact that semelfactives have GIVE-readings, as in (43), while degree achievements have GET-readings, as in (44):

-

(43)

-

a.

kop ‘a kick’ – kop-nou-t ‘give a kick’ (Cz)

-

b.

dotyk ‘a touch’ – dotk-ną-ć ‘give a touch’ (Pol)

-

c.

krzyk ‘a shout’ – krzyk-ną-ć ‘give a shout’ (Pol)

-

a.

-

(44)

-

a.

bledý ‘pale’ – bled-nou-t ‘get pale’ (Cz)

-

b.

slepý ‘blind’ – slep-nou-t ‘get blind’ (Cz)

-

c.

chudy ‘slim’ – chud-ną-ć ‘get slim’ (Pol)

-

a.

An argument for breaking the NU sequence into two separate morphemes comes also from the fact that the N appears without the U in environments other than semelfactive and degree achievement verbs. For example, we find the N morpheme with other theme vowels than U in passive participles in Polish (e.g. kop-N-ię-T-y ‘kicked’) and in nominalizations (e.g. kup-owa-N-ie ‘buying’, kop-a-N-ie ‘kicking’, Pol.).Footnote 22 Another context where we find the N morpheme without the U-theme is the Czech imperative, e.g. bled-n-ěte! ‘become pale!’.

4 N as a light verb

Before we discuss the light verb property of N in semelfactives and degree achievements, let us first point out the fact that both these categories have been occasionally argued to include the ingredient of the same semantic type. Notably, Rothstein (2004) proposed that the semantic element common for them is a natural atomic function. While from this perspective, the N morpheme can be hypothesized to spell out the natural atomic function, there are reasons to reject such a view in favor of the light verb theory of N. Consider the following.

4.1 Semelfactives and degree achievements in Rothstein (2004)

4.1.1 Natural subevents are necessary for semelfactives

There is an essential morphological difference between activity and semelfactive verbs that are created from the same roots in languages like English and Czech or Polish such that while English verb stems are structurally ambiguous between activity and semelfactivity, Czech or Polish verb stems are each created by a different theme: activity verbs include AJ, semelfactives NU. Consider the following examples with English wink and its Czech equivalent mrk-a-t.Footnote 23

-

(45)

-

(46)

Semantically speaking, the difference between activities like walk and semelfactives like wink concerns their natural subevents. Essentially, even if semelfactive verbs are used as activities as in (45a), there are easily identifiable single occurrences of subevents of wink while there are no such single occurrences of walk. In Dowty’s (1979) terms, these single occurrences are themselves the smallest events of the predicate P to the effect that an activity event has minimal parts (\(=P_{min}\)), which are the smallest events in P which count as events of P. Thus, events like winking comprise natural minimal events (single winks) but events like walking do not comprise such minimal events.

Assuming Dowty’s analysis, Rothstein (2004, 2008) distinguishes between semelfactives and activities on the basis of natural atomicity. A naturally atomic entity is the one which comes with a perceptually salient unit structure (marked by natural beginning and end points) given by the world (this includes the denotation of countable nominals like wink, kick, or jump) and the natural atomic function (NAF) is the function which picks out the set of minimal parts \(P_{min}\) of the predicate P, as defined in (47).

-

(47)

Natural Atomic Function (NAF)

“An activity predicate P will denote a set of events P, and will contain a subset \(P_{min}\), which is the set of minimal events in its denotation. If a predicate has a semelfactive use, then there will be a natural atomic function which picks out the set \(P_{min}\), and \(P_{min}\) will be an atomic set” (Rothstein 2004:186).

In other words, Rothstein submits that naturally atomic subevents are recognizable and referrable for semelfactives, but not for activities. The former ones denote events with natural beginning and end points, while the latter do not.

4.1.2 Scale is necessary for degree achievements

Rothstein observes that while natural subevents are necessary for semelfactives, degree achievements must comprise a scale.

We have observed in Sect. 3.3 that Czech and Polish degree achievement are derived from adjectival roots. Since the denotation of adjectives makes reference to scales, understood as ordered sets of degrees, the scalar structure is present in the denotation of degree achievements, as specifically argued for in Hay et al. (1999).

Consider the following examples with degree achievements in English from Rothstein (2004).

-

(48)

-

a.

The soup cooled for some hours.

-

b.

The sky darkened between 2 pm and 4 pm.

-

a.

Despite the fact that cool and darken have properties that make them similar to activities, for these sentences to be true, there must have existed intervals during which the single occurrences of cooling and darkening took place. In particular, Rothstein (2004:189) argues that the sky darkened does not denote a change from the state ‘not being dark’ to the state ‘being dark,’ rather, the darkening denotes changes of degrees on a scale of darkness such that the endpoint of one change is the starting point of the next change. A similar series of changes of a degree of coolness is a part of denotation of the soup cooled.

Assuming the denotation depends on changes of a degree along a scale, Rothstein draws a parallel between degree achievements and semelfactives based on natural atomicity. While NAF defines minimal parts of a predicate which have a beginning and an endpoint in semelfactives, in the case of scales, NAF defines the minimal degree of a change on that scale. This is in essence what seems to be a common ingredient in Czech and Polish semelfactive stems, which are all based on nominal roots, and degree achievement stems, which are all based on adjectival roots.

4.1.3 Challenges to the NAF analysis of N

Since semelfactive and degree achievement stems include different roots but stems of both categories include the morpheme N, it is tempting to suggest that N simply spells out NAF. Such a hypothesis would quite naturally hold that in the structure of semelfactive stems the morpheme N picks out the atomic event from the denotation of a nominal root, e.g. kop- ‘kick’, which is the single occurrence of the event \(P_{min}\). In the case of degree achievements, it could be hypothesized that the denotation of a minimal degree of a change on a scale is conditioned by the presence of the N morpheme in combination with the adjectival root.

Such an approach, however, is not free from problems. First, it remains unclear if the natural atomicity is really a grammatical feature lexicalized by the N morpheme (that is, NAF is part of the morphosyntactic representation) or the function in the denotation of the entire stem (as it is in the case of English semelfactives and degree achievements). Second, if N is supposed to spell out NAF, it is unclear what NAF picks out from typically verbal roots that also merge with N in examples listed in (41)–(42). The existence of such forms in fact rules out the NAF hypothesis of N, as the resulting stems in these two examples are clearly activities. If Rothstein’s natural atomicity remains the function in the denotation of the entire category rather than part of the morphosyntactic representation, the problem of what N spells out remains.

4.2 The light verb theory of N

Instead, we argue below that N is a light verb, whose grammatical ingredients are responsible for GIVE and GET readings of semelfactive and degree achievement stems, respectively.

4.2.1 Layers of the light verb structure

We submit that N is a light verb which includes abstract GET and GIVE such that GET is contained in the structure of GIVE, as in the following:Footnote 24

-

(49)

The light verb structure of the N morpheme in Czech and Polish is genuinely similar to the decomposition of the light GIVE in English into ‘GIVE > GET > possessive HAVE’, which is manifested in the fact that both lexical get and give integrate a possessive functor, which is indicated in English by the restatements with have:

-

(50)

-

a.

John gave Mary the book. → John caused Mary to have the book.

-

b.

Mary got the book. → Mary came to have the book.

-

a.

A frequently cited argument (e.g. Ross 1976; Dowty 1979; Beavers et al. 2009) in favor of an underlying possessive HAVE state in lexical give and get in English is that it can be modified by durative for-adverbials:

-

(51)

-

a.

John gave Mary the book for two weeks. → have the book for two weeks.

-

b.

Mary got the book for two weeks. → have the book for two weeks

-

a.

A particularly interesting argument in favor of the decomposition of the lexical give as comprising both light GET and possessive HAVE comes from Richards (2001), who shows that there are idioms which consist of an object and a part of a lexical verb give in which case it has the GET-reading.Footnote 25 Richards (2001) adopts Harley’s (1997, 2003) structure of the lexical verb give as in (52), which incorporates HAVE.

-

(52)

[x CAUSE y [HAVE DP]]

-

a.

John gave Mary the book.

-

b.

John CAUSE Mary [HAVE the book].

-

a.

In Harley’s analysis, sentences like in (52a) differ from to-dative sentences like John gave the book to Mary in that the latter do not incorporate the possessive HAVE.Footnote 26 On this basis, Richards (2001) observes that there is a class of give idioms which obligatorily involve the structure in (52), as the idiom is broken when the double object form is not used:

-

(53)

-

a.

The Count gives Mary the creeps.

-

b.

*The Count gives the creeps to Mary.

-

a.

-

(54)

-

a.

Mary gave John the sack.

-

b.

*Mary gave the sack to John.

-

a.

-

(55)

-

a.

Mary gave Susan the boot.

-

b.

*Mary gave the boot to Susan.

-

a.

This contrast signals that double object sentences do not inevitably involve a separate predicate HAVE but rather the meaning of a possessive HAVE is part of a ditransitive predicate. Importantly, Richards points out that the idiomatic part is smaller than give DP, since it is preserved with get:

-

(56)

-

a.

Mary got the creeps.

-

b.

John got the sack.

-

c.

Susan got the boot.

-

a.

This leads Richards to conclude that the idiomatic part is only [HAVE DP] which is lexicalized as part of a monotransitive get DP or a ditransitive give DP in English. Since the GET-reading is part of the GIVE-reading there exists a containment relation between GIVE and GET and GET and possessive HAVE.

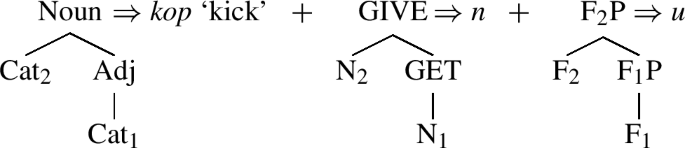

As indicated in (43)–(44), the merger of N+U with the root produces a stem which has a GIVE-reading or a GET-reading. Since the theme vowel U turns the structure into a verb stem—just like all the other themes do—and together with the root it merges with is responsible for the argument structure properties of the stem (including its case), it is the morpheme N that appears to be the locus of the light GIVE and GET readings. The fact that degree achievements stems have GET-readings suggests that their adjectival roots merge with the light verb of the following size, a subset of (49):

-

(57)

In turn, the fact that semelfactive stems have GIVE-readings, suggests that their nominal roots merge with a light verb with an additional layer of structure, a superset of (49). Under such an analysis of the N morpheme, its lexical entry is as follows:

-

(58)

N: /n/ ⇔ [\(_{GIVE}\) N2 [\(_{GET}\) N1]]

Recall that due to the Superset Principle in (10), both representations in (49) and (57) are spelled out as N. We have, thus, identified the first contrast in the sizes of morphemes forming degree achievement and semelfactive verb stems: the lexical entry for the light N morpheme in a degree achievement stem includes a subset of the syntactic structure of the lexical entry for the light N in a semelfactive stem.

It must be noted that the fact that the English light “give DP” (give a kick) and “get Adj” (darken, get dumber) have the form of “nominal root + N” (kop-N-ou-t) and “Adj + N” (hloup-N-ou-t) in Czech and Polish is not by itself the argument for the existence of the light verb N. The argument is the valency identity between these forms. That is, while English “give DP” is causative, so is the Czech and Polish “nominal root + N”. This is well visible below, where a nominal root with the light N in (60) corresponds to a direct object of the lexical dać ‘give’ in the Polish example (59).

-

(59)

-

(60)

The same is true about light verbs like darken or periphrastic get dumber and “Adj + N” mergers in Czech and Polish: both are exclusively unaccusative, which we return to shortly.

4.2.2 Light GIVE and GET in Persian

An argument supporting the analysis of the facts discovered to hold inside Czech and Polish NU-stems comes from Persian, where a formation of a semelfactive stem involves a merger of a nominal preverb with a light verb dadæn ‘give’.Footnote 27

In Persian, the majority of verbal predicates are built by merging a non-verbal part, the so-called preverb, with a light verb (which includes verbs like kærdæn ‘do’, shodæn ‘become/get’, amædæn ‘come’). The preverbs can belong to different categories: nouns, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, or PPs. However, a few light verbs merge with preverbs of only a particular lexical category. Such a category restriction holds in the case of the light verb dadæn ‘give’, which builds semelfactives and accomplishments, and which merges only with nominal preverbs and occasionally with prepositions (cf. Folli et al. 2005; Pantcheva 2009). Whether a semelfactive or an accomplishment verb is produced depends on the type of noun dadæn merges with. For instance, in the examples from Family (2014:109), three nouns denoting rotation—twist, turn, and roll, produce semelfactives when merged with dadæn:

-

(61)

Here, again, just like in Slavic NU-stems or English semelfactives of the form ‘give a kick’, the semelfactive involving dadæn ‘give’ is always causative, as in:

-

(62)

There are two non-causative variants of dadæn ‘give’: light verbs gereftæn ‘get’ and shodæn, literally ‘become/get’ (Pantcheva (2009) classifies them as resultative versions of dadæn ‘give’, which both lack an initiator of an event in Ramchand’s (2008) decomposition of the event structure). While gereftæn ‘get’ corresponds to English change-of-possession get, as in (63) below, it is shodæn ‘become/get’ which corresponds to a change-of-state get in degree achievements like get dumber, or Czech hloup-N-ou-t.

-

(63)

Unlike dadæn ‘give’, it can merge with adjectival preverbs, as in (64) (where the possibility to modify the “gradable adjective + shodæn” complex by both for- and in-adverbials indicates that it forms a degree achievement, given the claim in Ramchand (2008) about the telic/atelic status of such stems):

-

(64)

This is exactly the scenario that we find to hold inside the semelfactive stems in Czech and Polish.

4.2.3 Change-of-possession and change-of-state light GET

Putting the Persian facts aside, it could be hypothesized that in English, the ‘GIVE > GET’ inclusion is restricted only to the change-of-possession relation and does not show up in the change-of-state GET. Such a supposition, however, must be rejected. Richards’ (2001) observation about English idioms which consist of an object and a part of a lexical give, in which case it has the GET-reading, quite clearly reveals that both change-of-state and change-of-possession GETs are related by comprising a possessive HAVE. This is illustrated by a subset of change-of-possession GIVE/GET idioms that are retained with a change-of-state GET, e.g.:

-

(65)

-

a.

John gave Mary a sack.

-

b.

Mary got a sack.

-

c.

Mary got sacked.

-

a.

-

(66)

-

a.

Susan gave Mary a boot.

-

b.

Mary got a boot.

-

c.

Mary got booted.

-

a.

-

(67)

-

a.

John gave Mary an evil eye.

-

b.

Mary got an evil eye (from John).

-

c.

Mary got evil eyed (by John).

-

a.

It is, thus, quite clear that the core of the GET-reading is the change itself, namely

-

(i)

change-of-possession as part of the lexical get or give, and

-

(ii)

change-of-state as part of only the lexical get, not give.

In degree achievements, we never have a change-of-possession, only the change-of-state reading of GET (based on the adjectival root) in the following format:

-

(68)

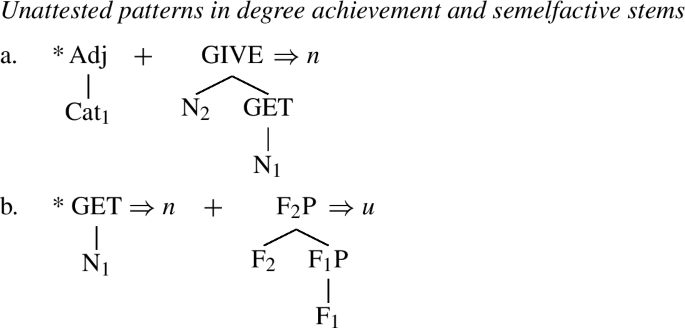

Semelfactive stems in Czech and Polish have a clear GIVE-reading (i.e., GET plus more). But in this case, this GET requires a possession, not a state. So, starting with a possessed object like kop- ‘a kick-’, it is not enough to merge it with the light GET only, as such a structure does not correspond to any attested stem:

-

(69)

Instead, in the case of semelfactives, the light verb structure must be bigger and it has to grow all the way to GIVE-layer, that is the bigger N-suffix of (49).

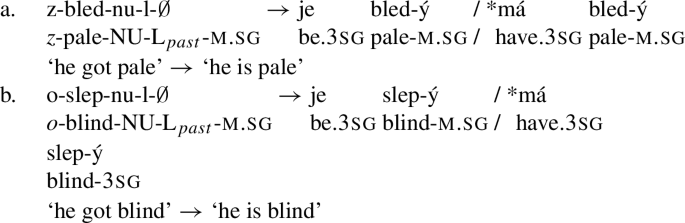

4.3 Slavic ‘GIVE > GET’ without HAVE

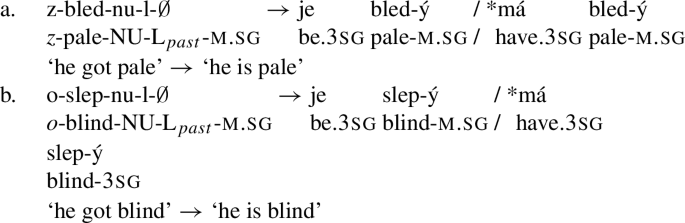

In Czech and Polish, nothing suggests that there is HAVE lower than GET. Instead, the ‘resultant state’ of degree achievements is expressed with an adjective with a separate auxiliary verb BE, not HAVE, as illustrated on the example of Czech in:Footnote 28

-

(70)

The light N in degree achievement does not have the HAVE-reading, not even in the exceptional degree achievement stem mrzout ‘get cold’ (discussed in fn. 17), which can get a stative reading, as shown in (71).

-

(71)

For the purposes of describing the light verb properties of the N morpheme, it is sufficient to observe that it has GIVE- and GET-readings, while it lacks possessive HAVE-readings. For this reason, the HAVE-layer is absent from the structural representation of the N-morpheme in (49).Footnote 29

4.4 Light GIVE, GET, and root selection

The situation in which the GIVE-readings and the GET-readings of N-stems are restricted by the category of the root indicates that the merger of the N morpheme with the root is regulated by selection whereby a bigger N\(_{GIVE}\) merges with nominal roots and a smaller N\(_{GET}\) merges with adjectival roots. It, thus, appears that the size of the morpheme N—in particular, the presence of the top GIVE layer in the structure of the light verb—depends on the category of the root it merges with. It must be observed that the relation between the size of the N morpheme and the category of the root can be reduced to a general size-to-size selectional relation under a containment theory of lexical categories put forward in Starke (2009).

According to the containment theory, detailed in Lundquist’s (2008) analysis of the structure of Swedish participles, lexical categories are not primitive but structurally complex such that adjectives are smaller than nouns which are, in turn, smaller than verbs, as simplified in (72).Footnote 30

-

(72)

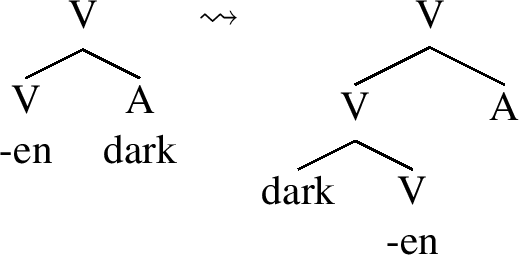

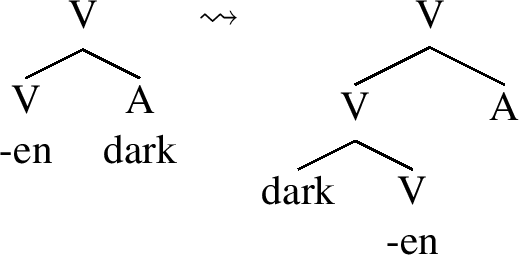

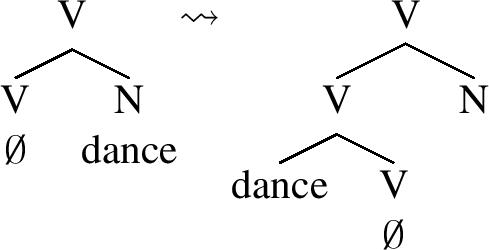

As discussed at length in Lundquist (2008), the idea that verbs structurally contain nouns and adjectives is not new and has been based on an observation that the more functional structure that participles and nominalizations contain, the more verbal syntactic properties they exhibit. Likewise, participles and nominalizations behave like non-derived adjectives and nouns if they contain a smaller functional structure. This general observation constitutes the basis of Hale and Keyser’s (2002) theory of the formation of deadjectival (e.g. darken) and denominal (e.g. dance) verbs. These classes of verbs are argued to be derived by conflation, that is, the merger of an adjectival or a nominal root with a verbal head in the lexical representation, as outlined below:Footnote 31

-

(73)

-

(74)

Similarly, verbs are analyzed as categories bigger than adjectives in Baker (2003). Apart from analyzing verbs as categories composed of adjectives merged with the Predication head in syntax, Baker also observes that the internal argument of verbs usually corresponds to the external argument of adjectives:

-

(75)

-

a.

John hungers.

-

b.

John is hungry.

-

a.

-

(76)

-

a.

John likes mushrooms.

-

b.

John is fond of mushrooms.

-

a.

Assuming the Universal Thematic Hierarchy (UTAH), Baker concludes that this fact makes the argument structure of a verb derived from a smaller argument structure of an adjective.

The idea that verbs are bigger than nouns and adjectives has been supported more substantially than the idea that nouns are bigger than adjectives. Though, apart from Lundquist (2008), Baker’s (2005) theory of lexical categories lists adjectives as the most basic category devoid of both nominal structure (“the referential index”) and the verbal structure (“a specifier”).

If the avenue of the lexical containment between nouns and adjectives as in (72) is on the right track, then we must state that the syntactic structure of the root in degree achievements is a subset of the syntactic structure of the root in semelfactives. This constitutes the second difference in syntactic sizes of morphemes in these stems after the contrast in the size of the light N morpheme giving the emerging picture as follows: semelfactives are formed by a nominal root and the light N\(_{GIVE}\), while degree achievements are formed by their subsets, the adjectival root and the light N\(_{GET}\).

The merger between the varying sizes of the light N morpheme and different lexical categories of roots does not appear to be accidental but rather an instance of a size-relative selection. We have observed that a smaller N\(_{GET}\) selects for adjectival roots, while a bigger N\(_{GIVE}\) selects only for nominal roots, which are bigger than adjectives in the lexical containment theory, as outlined in (77). (Since the spans of syntactic projections indicated in the diagrams below do not constitute morphemes at this early derivational stage when selection takes place, we are referring to them simply as ‘zones’ rather than ‘morphemes’).

-

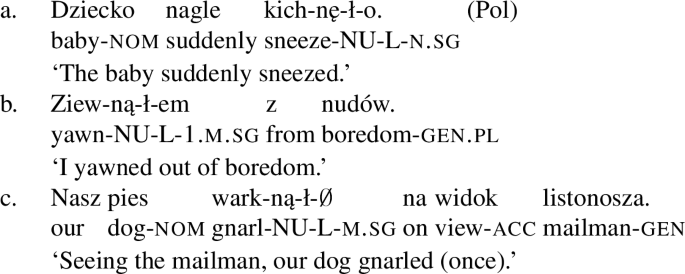

(77)

We will observe another instance of the size-to-size selectional restriction taking place in the Slavic verb stem in Sect. 5.2 when we discuss the properties of the thematic suffix U, which completes the morphological make up of NU-stems.

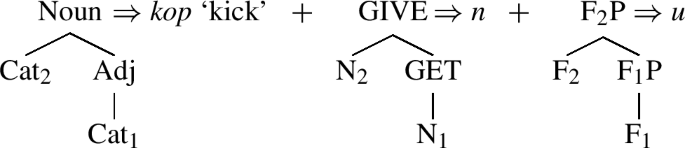

4.5 Spelling out the light N zone

In the model of phrasal spell out, the insertion of a lexical material at a phrasal node requires that the representation to be lexicalized forms a constituent. The representations in (77) do not match the lexical entry in (58). The lexicalization of these structures is obtained by spell out driven movement of the root zone, in the same way the lexicalization of the case fseq is obtained by the movement of the NP outlined in Sect. 2.2.

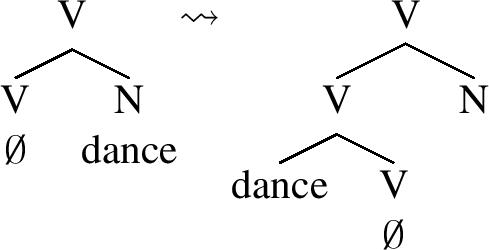

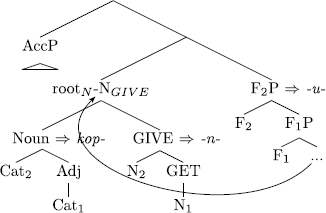

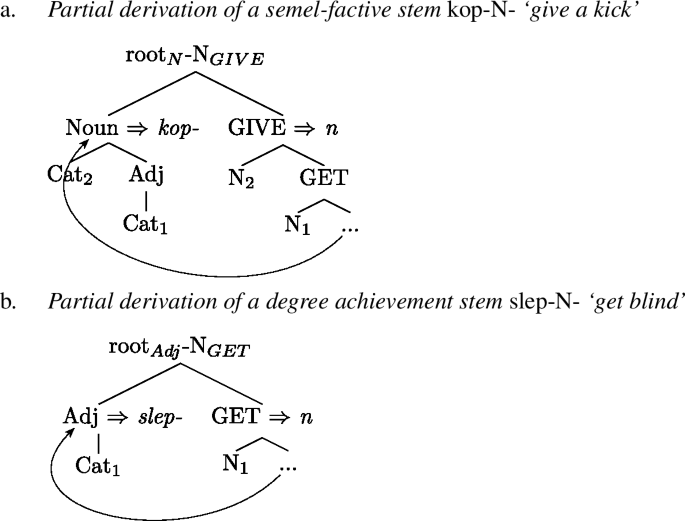

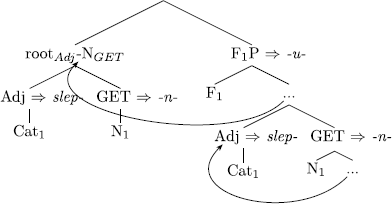

Following the logic in Starke (2009) and Caha (2011b), it is the shape of a lexical entry that triggers movement. In particular, in a model in which each application of external merge is followed by lexical access, it is the lexical access that determines the way the syntactic derivation proceeds. Consider the partial derivations of a Czech and Polish noun-based stem kop-N- as in a semelfactive kopnout ‘give a kick’ and an adjective-based stem slep-N- as in a degree achievement slepnout ‘get blind’ at a stage before the thematic morpheme U is merged.

-

(78)

The evacuation movement that targets a sister to node N1 in (78a) derives a constituent that matches the lexical entry for /n/ in (58). The height of the evacuation movement in (78b) is delimited by the node GET, which results in the formation of a constituent like in (57). Due to the Superset Principle, this constituent also spells out as /n/. In principle, there is nothing that prohibits the moved constituent to include other layers of structure than the ones in (78). However, the lexical entry for /n/ has N1 at the bottom, so any movement that does not create a constituent with N1 at the foot will not spell out as /n/.Footnote 32

Once an evacuation movement of the root zone takes place and a constituent that matches a lexical entry is formed, the structures become input to further external merge. In the case at hand, the fseq that forms the theme U zone, the other part of the split N+U sequence, becomes merged. We discuss the U theme in the next section.

To sum up, the partial structure of both types of stems discussed so far looks, thus, as follows:

-

(79)

-

a.

semelfactive: [[ N-root] \(\mathrm{N}_{\mathit{GIVE}>\mathit{GET}}\)]

-

b.

degree achievement: [[ Adj-root] \(\mathrm{N}_{\mathit{GET}}\)]

-

a.

In what follows, we show that both these types of stems have different syntactic properties, which reflects the different amounts of syntactic structure spelled out by the theme vowel U.

5 U theme and argument structure properties of NU-stems

Splitting the NU part of the stem into separate morphemes N and U makes it possible to link the internal syntax of semelfactive and degree achievement stems with their argument structure properties. The major observation behind this premise is that while both semelfactive and degree achievement stems have the same morphological makeup comprising the root, the N morpheme and the theme vowel U, they display different argument structure properties. Since, as argued above, the N morpheme has the properties of a light verb, the morpheme which determines, though indirectly, the argument structure properties of NU-stems is the thematic suffix U. In other words, the theme U is responsible for argument structure properties just like the other themes are.

5.1 Unaccusative degree achievements, accusative or unergative semelfactives

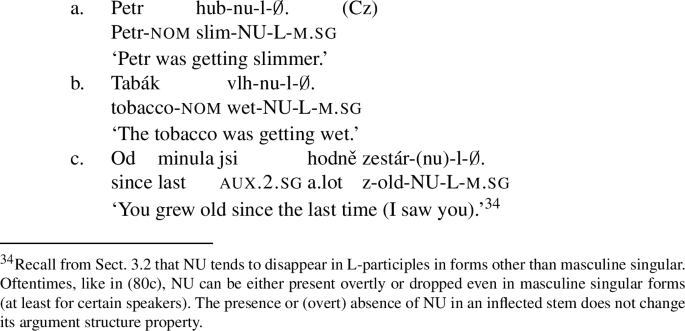

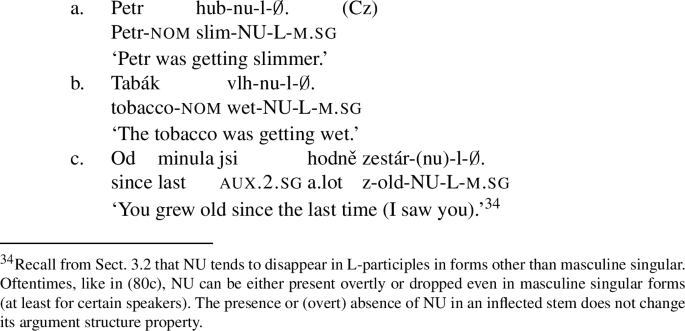

The corpus analysis of Czech and Polish semelfactive and degree achievement verbs based on NU-stems leads to the generalization that while degree achievement stems are all unaccusative, semelfactive stems are either transitive/accusative or unergative.Footnote 33 Some examples of Czech and Polish unaccusative degree achievements are given in (80)–(81).

-

(80)

-

(81)

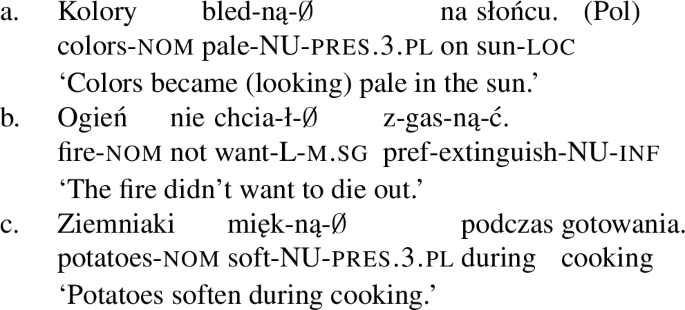

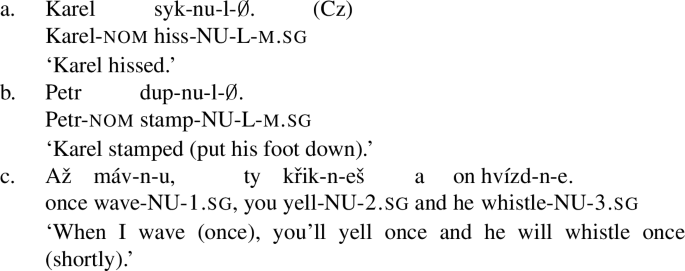

Unlike degree achievements, semelfactive NU-verbs are either transitive/accusative or unergative. Examples of transitive/accusative semelfactives are given in (82)–(83).

-

(82)

-

(83)

Finally, examples of unergative semelfactives are given in (84)–(85).Footnote 34

-

(84)

-

(85)

5.2 Theme vowel U

Descriptively speaking, theme vowels are verbalizing morphemes, which participate in encoding the argument structure properties of verb stems. This is perhaps best illustrated by those themes which can merge with a single root, in which case we observe the causative-inchoative alternations as in (86).

-

(86)

Examples of causative-inchoative alternations

unaccusative N+U

accusative I

marz-ną-ć

‘get cold’

mroz-i-ć

‘freeze (something)’

(Pol)

mięk-ną-ć

‘get soft’

mięk-cz-y-ć

‘make (something) soft’

(Pol)

mok-nou-t

‘get wet’

moč-i-t

‘soak (something)’

(Cz)

chlad-nou-t

‘get cold’

chlad-i-t

‘make (something) cold’

(Cz)

For instance, a root marz- ‘cold’ builds an unaccusative (degree achievement) stem by merging with N+U, as in Wszyscy marz-ną ‘Everybody is getting cold’, but when merged with a causative theme vowel I, it builds an accusative stem, as in Jan mroz-i piwo ‘Jan is cooling the beer’. Essentially, the causative I-stem is always accusative and the NU∼I alternation is rather common in both languages.Footnote 35

The syntactic properties of Polish thematic suffixes have been detailed in Jabłońska (2007), where it is argued convincingly that they spell out layers of a fine-grained vP/VP structure.Footnote 36 The thematic structure properties of the thematic suffixes in contemporary Czech and Polish are summed up in the following table. Starting at the bottom, there are two rather exceptional classes: the Ø thematic suffix (a result of historical changes in morphophonology) and the theme -OVA- (apart from N+U, the only thematic suffix productive in contemporary Czech and Polish).Footnote 37

-

(87)

Summary of argument structure properties of Czech and Polish themes

semantic class

theme vowel

argument structure

verb class

example

gloss

causative

I

Ag+Th

acc

top-i-t

‘drown sb’

iterative/habit.

AJ

Ag+Th

acc

klek-a-t

‘kneel (iter.)’

semel#1

(N-)U

Ag(+Th)

unerg

klek-nou-t

‘kneel’

semel#2

(N-)U

Ag+Th

acc

kop-nou-t

‘kick sb’

become#1

(N-)U

Th

unacc

bled-ną-ć

‘get pale’

become#2

EJ

Th

unacc

plan-ej-t

‘get wild’

stative

E

Th/Exp

unacc

kleč-e-t

‘kneel’ (stative)

causative/all

OVA

Ag+Th

acc

stud-ova-t

‘study’

causative/all

Ø

Ag+Th

acc

nés-Ø-t

‘carry’

While the general approach to thematic suffixes in what follows and in Jabłońska’s work is similar, for space reasons, we are restricting the discussion of argument structure properties of Slavic theme vowels to a minimum necessary to understand the general similarity of the U theme with other themes like I or AJ, which are clearly responsible for the syntactic properties of the verb stems they build.

Suffice it to say, Czech and Polish themes do not simply encode bare argument structure but rather the structural properties that are a part of the aspectual event structure. That is, while the theme vowel I is an exponent of a suffix that builds causative stems, another theme vowel AJ builds activity stems (iteratives and habituals), which are both unergative and/or transitive, just like semelfactive NU-stems. Many roots which build either unergative or accusative NU-semelfactive stems can instead merge with the AJ-theme, as in (88). Such a combination creates an activity stem with unergative syntax. Also this alternation is common in both Polish and Czech.

-

(88)

Examples of semelfactives and activities alternations

unergative or accusative N+U

unergative AJ

liz-ną-ć

‘lick once’

liz-a-ć

‘lick’

(Pol)

kop-ną-ć

‘give a kick’

kop-a-ć

‘keep kicking’

(Pol)

štěk-nou-t

‘give a short bark’

štěk-a-t

‘bark’

(Cz)

klik-nou-t

‘click once’

klik-a-t

‘keep clicking’

(Cz)

On the proviso that a separate morpheme N spells out the structure responsible for GIVE/GET readings, the morpheme which lexicalizes the syntactic structure that comes out unaccusative, accusative, and unergative in NU-stems is the theme U. In a system in which spell out targets subconstituents rather than terminal nodes, this indicates that the syntactic representation of the U theme spans across several layers of the syntactic event (or “VP”) structure. While the ongoing work on the VP structure, usually couched within the variants of the “accusative little vP” > “unaccusative VP” split approach based on Hale and Keyser (2002) and Kratzer (1996), differs with respect to what heads the articulate VP is made of, it has been established that an unaccusative VP is structurally smaller than an accusative VP (at the very least in the way that it includes a layer of structure that contains an accusative object).

In turn, the fact that external arguments are merged higher than accusative objects indicates that they are introduced by another higher head in the eventive verbal structure. For this reason, unergatives have been argued to be structurally similar to accusatives rather than unaccusatives (see for instance Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995) or Ramchand (2008), who argue that both unergatives and accusatives differ from unaccusatives in that they include the layer of structure with event initiators as arguments). An often reported structural proximity between unergatives and accusatives is also manifested by the fact that certain NU semelfactives are either unergative or accusative. Oftentimes, such an alternating verb will receive a non-literal reading as in (89), where the unergative semelfactive ‘whistle’ in (89a) has a non-literal meaning ‘steal’ if it is an accusative semelfactive, as in (89b).

-

(89)

The situation in which a singleton morpheme U lexicalizes a syntactic representation which includes projections bigger than unaccusative constitutes an argument in favor of the phrasal spell out of a (part of) the eventive verb structure in the same way as a single case morpheme lexicalizing representation that contains other cases does. For the case at hand, the theme U spells out the lowest unaccusative projection as part of degree achievement stems and bigger accusative and unergative projections as part of semelfactive stems as in the following representation in (90), which captures the ‘unergative > accusative > unaccusative’ distinction:Footnote 38

-

(90)

The lexical span of U stretches further up to at least one layer, F3P in (90), atop the accusative structure and excludes higher layers of the unergative structure. This correctly captures the observation that not only does U spell out as unaccusative, accusative and unergative but also that there is (at least) one other morpheme which spells out as unergative, namely the AJ theme, which builds activity stems (cf. (88)). In other words, U is syncretic for unaccusatives, accusatives and (lower) unergatives and the lexical entry for the unergative AJ theme is bigger than the lexical entry for U.

Note that the fact that U spells out unaccusative, accusative, and unergative while AJ spells out only unergative structure is in concert with the *ABA constraint. Recall from Sect. 2.1 that the *ABA states that in nested structures, a more complex structure and a less complex structure are not spelled out as an exponent A, if structures that are in between them in terms of complexity are spelled out as an exponent B. Thus, the hypothetical *ABA scenario for the ‘unergative > accusative > unaccusative’ hierarchy of structural complexity would be that the AJ theme spells out accusatives and the U theme spells out unergatives and unaccusatives, counter fact. The representation of the argument structure hierarchy as the syntactic tree allows us to explain why such a scenario is unattested, namely the syncretic span of the U theme is restricted only to a contiguous region of (90).

The lexical entry for the thematic morpheme U, whose exponent is /u/ in Czech and /ą/ in Polish, is given in (91), and the syntactic constituents which on the strength of the Superset Principle can spell out as U in (92).

-

(91)

Lexical entry for U

U: /u/ (Cz), /ą/ (Pol) ⇔ [ F3[ AccP peel [ F2[ F1]]]]]

-

(92)

Constituents spelled out as the thematic suffix U in Czech and Polish

-

a.

U: /u/ (Cz), /ą/ (Pol) ⇔ [ F3[ AccP peel [ F2[ F1]]]]]

-

b.

U: /u/ (Cz), /ą/ (Pol) ⇔ [ F2 [ F1]]

-

c.

U: /u/ (Cz), /ą/ (Pol) ⇔ [ F1]

-

a.

The lexical entry for U in (91) includes an AccP peel, that is the AccP stranded by the extraction of a lower NomP, a scenario discussed in Sect. 2.3. The extraction of the NomP subconstituent strands the AccP layer of the case fseq as part of the tree representation which is spelled out as the thematic suffix U, the issue we return to shortly. The subconstituents in (92b) and (92c) are also spelled out as U due to the Superset Principle in (10).Footnote 39

Despite the fact that the theme vowel U spells out part of the fseq of the eventive verbal structure, it is imprecise to state that it is solely responsible for the argument structure properties of NU-stems. Otherwise, we would expect any kind of a NU-stem, that is both degree achievements or semelfactives, to come out as unaccusative, accusative or unergative, contrary to fact. Instead, the relation between how much argument structure U spells out is dependent on the syntactic size of the root and the light N morpheme. Namely, a small root zone (descriptively speaking, an adjectival root) and a small N zone (the light GET) as in (77b) merge with a small thematic U zone, while a bigger root zone (a nominal root) and a bigger N zone (the light GIVE) as in (77a) merge with bigger U zones. Assuming the hierarchical ‘unergative > accusative > unaccusative’ VP structure, we observe a size-relative selection between the U theme and the root+N constituent, the type of selection which we earlier observed to hold between the light N and the root, a situation which we will return to shortly.

To sum up, together with the U-theme, the structure of both types of semelfactive (unergative and accusative) and unaccusative degree achievement stems look as follows:

-

(93)

-

a.

semelfactive #1: [[[ N-root] \(\mathrm{N}_{\mathit{GIVE}>\mathit{GET}}\)] \(\mathrm{U}_{\mathit{unerg}>\mathit{acc}>\mathit{unacc}}\) ]

-

b.

semelfactive #2: [[[ N-root] \(\mathrm{N}_{\mathit{GIVE}>\mathit{GET}}\)] \(\mathrm{U}_{\mathit{acc}>\mathit{unacc}}\) ]

-

c.

degree achievement: [[[ Adj-root] \(\mathrm{N}_{\mathit{GET}}\)] \(\mathrm{U}_{\mathit{unacc}}\) ]

-

a.

6 Spelling out NU-stems

With the selectional restriction and the shape of the lexical entry for the U-theme in (91) in place, it remains to be explained how the attested morpheme order and argument structure properties of degree achievement and semelfactive stems become derived. Let us first work with the smallest stem, the unaccusative degree achievement, before we move on to bigger semelfactive stems.

6.1 Unaccusative degree achievements

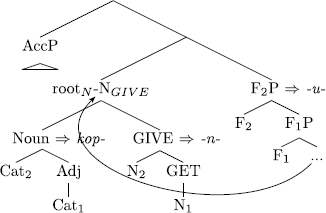

The smallest part of the syntactic structure that spells out as U comprises only the bottom projection of the U-zone, that is F1P of (90)/(92c). Its merger with an adjectival root and a small light N\(_{GET}\) as in (78b) derives a sequence of projections as in (94) (with the root and the light N zones already forming constituents that spell out slep-N- in a degree achievement stem ‘get blind’).

-

(94)

Lexicalization of an unaccusative degree achievement stem

e.g. Karel slep-n-u-l. ‘Karel was getting blind.’ (Cz)

While (78b) matches the lexical entries, the sequence with F1P merged on top of it does not match any. Since each merge is followed by an immediate lexical access, the slep-N- constituent moves up and remerges as the sister to the node where the lexical entry which triggers its evacuation is to be inserted. The derived constituent F1P is spelled out as /u/ in Czech (as in Karel slep-n-u-l, ‘Karel was getting blind’) or as /ą/ in Polish (as in Karol ślep-n-ą-ł), in concert with (92). Since only the smallest layer of the fseq making up the theme U zone is projected on top of a small light N\(_{GET}\), /u/ in degree achievement stems comes out as unaccusative.

6.2 Accusative semelfactives

In line with the observation that there is a size-relative selectional restriction, the U zone of a size comprising (at least) one more layer of its fseq, that is F2P on top of F1P, merges with a bigger nominal root and a bigger light N\(_{GIVE}\) as in (78a), as for instance kop-N- in a semelfactive stem ‘give a kick’ in (95). Such a representation with F2P on top and the root at the bottom, again, does not match any lexical entry and a spell out driven movement of an already spelled out constituent takes place. The evacuated constituent remerges as the sister to the node where the lexical entry which triggers its movement is to be inserted.

-

(95)

Lexicalization of an accusative semelfactive stem e.g. Petr kop-n-u-l psa. ‘Petr kicked the dog (once).’ (Cz)

Since every application of merge is followed by lexical access, the derived constituent [ F2[ F1]] becomes spelled out as /u/ in line with (92b). This bigger span of the U-theme zone comes out as accusative. According to Caha’s theory of case, the presence of an accusative NP as part of a syntactic structure of a certain size indicates that a selection of an AccP takes place at that level. In line with case representation outlined in Sect. 2, the AccP is an internally complex phrase which dominates NomP on top of the NP.Footnote 40

Perhaps the most robust prediction of the relation between the syntactic size of the thematic U morpheme and the size of the N morpheme is that NU-stems with GET-readings are only unaccusative, while NU-stems with GIVE-readings are either accusative or unergative. We have not found an exception to this generalization in Czech or Polish.

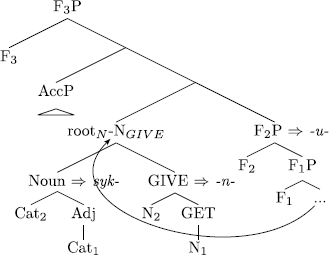

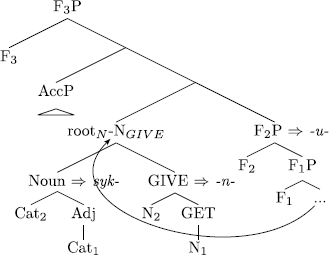

6.3 Unergative semelfactives

The derivation of the unergative semelfactive proceeds exactly like in (95) but it is then further extended by the merger of another layer of the thematic structure, F3P as for instance in Czech syk-N- in a semelfactive stem ‘hiss (once)’ in (96).

-

(96)

The merger of F 3 P layer on top of an accusative stem

e.g. Karel syk-n-u-l. ‘Karel hissed (once).’ (Cz)

The newly added feature F3P is followed by lexical access but, again, the tree as in (96) does not match any existing lexical entry.

In order to spell F3 out, two evacuation movements must take place: the second movement of syk-N- to a sister position of F3P (i.e. a node which triggers this evacuation movement) and the subextraction of the NomP from the AccP, as shown below:

-

(97)

Lexicalization of an unergative semelfactive stem

e.g. Karel syk-n-u-l. ‘Karel hissed (once).’ (Cz)

The subextraction of the NomP leaves the AccP-layer in its base position, in which it becomes spelled out as part of the lexical entry for the U theme in (91).Footnote 41

Note that the shape of the lexical entry for the U-theme which includes the peel of the accusative case-shell directly implies that the NP-argument of an unergative predicate starts low as an internal argument and is remerged as an external argument only later in the derivation. Such an analysis of unergatives is advanced in Taraldsen (2010b), who observes that Norwegian sentences with unergative participles have agentive get-passive readings. For space reasons, we leave this issue at this point.Footnote 42

6.4 Argument realization in an unergative superstructure

Let us bring up the issue of the relation between the unergative superstructure in the hierarchy in (90) and argument realization. More specifically, we need to address the following question: if, by our assumption, the unergative structure contains both the unaccusative and accusative structures, how does the accusative argument ‘go away’ in the unergative structure?

A possibility that comes up naturally in the domain we are looking at is that an argument which is a part of the unaccusative structure does not ‘go away’ at all but is preserved in the form of the nominal root of the unergative verb—in the way predicted by Hale and Keyser’s (2002) analysis of English unergatives.

Let us recall one more time that the roots of both accusative and unergative semelfactive verbs are nominal. As outlined earlier in (74), Hale and Keyser’s (2002) theory of the formation of unergative verbs submits that nouns like dance, run, talk first merge with and then undergo conflation with an abstract transitive V-head to form verbal predicates dance, run, talk. This effectively yields unergative structures which comprise a transitive V and a nominal root, a constituent that is further (minimally) extended by an external argument.Footnote 43

The view that unergative VPs include a transitive V-head and its nominal complement is particularly transparent in those Slavic semelfactives which alternate between unergative N+U stems and periphrastic monotransitive ‘give NP’ structures, as shown below (where dać is a lexical verb ‘give’):

-

(98)

-

(99)

In (98), we see a semelfactive verb stem which comprises a nominal root sus ‘leap’, the light GIVE suffix N, and the unergative theme vowel U. In (99), which can be described as a periphrastic semelfactive construction, we see the same root with the accusative case suffix sus-a ‘leap-acc’ appearing as the object of the lexical transitive verb dać ‘give’. In other words, such unergative–accusative pairs inform us about the relation between the argument of an accusative semelfactive and the unergative semelfactive verb in a similar way as the valency identity between a double transitive verb ‘give’ and its accusative argument kop ‘kick’ as in (100) informs us about the presence of the light GIVE applied to kop ‘kick’ in (101):

-

(100)

-

(101)

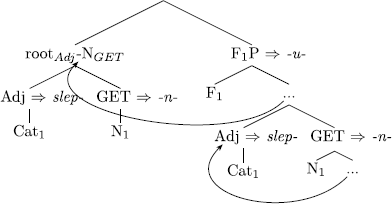

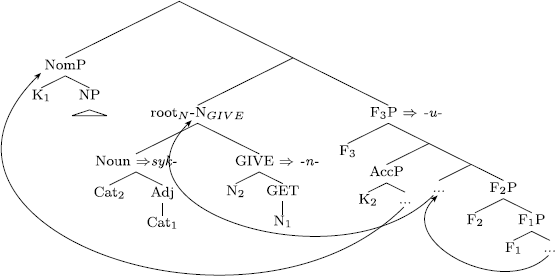

7 Selectional restrictions between the three fseq zones

Let us return to the observation that there is a size-to-size selectional restriction which holds (i) between the light N zone and the root zone and (ii) between the theme zone and the light N zone.

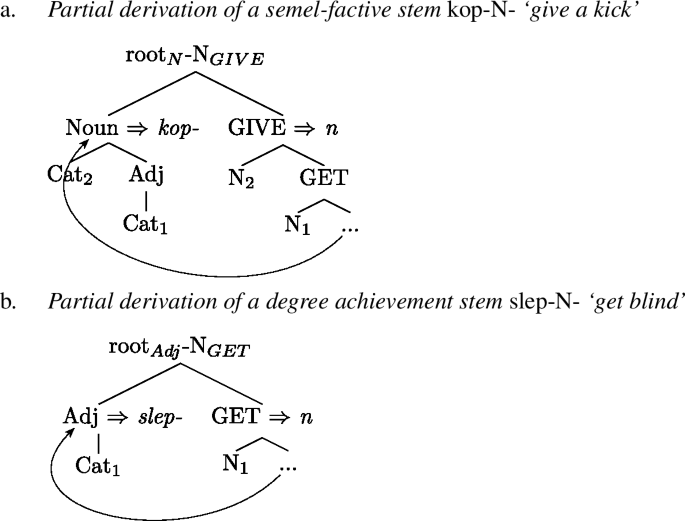

We have seen that degree achievement stems comprise the smallest subsets of all three fseqs of the morphemes they are made of: the adjectival root, the light GET, and the unaccusative U-theme, as in the Czech (uninflected) stem slep-n-u- ‘get blind’:

-

(102)

In turn, we have seen that semelfactive stems comprise the supersets of the morphemes they are made of: the nominal root and the light GIVE and either the bigger subset of the accusative U-theme, as in the Czech (uninflected) stem kop-n-u- ‘give a kick’ and synk-n-u- ‘hiss once’, respectively:

-

(103)

-

(104)

7.1 Chinese menu