Abstract

We argue that head movement, as an operation that builds head-adjunction structures in the syntax, has been used to model two empirically distinct classes of phenomena. One class has to do with displacement of heads (fully formed morphological words) to higher syntactic positions, and includes phenomena like verb second and verb initiality. The other class has to do with the construction of complex morphological words and is involved in various types of word formation. Based on the very different clusters of properties associated with these two classes of phenomena, we argue that they each should be accounted for by distinct grammatical operations, applying in distinct modules of the grammar, rather than by the one traditional syntactic head movement operation. We propose that the operation responsible for upward displacement of heads is genuine syntactic movement (Internal Merge) and has the properties of syntactic phrasal movement, including the ability to affect word order, the potential to give rise to interpretive effects, and the locality associated with Internal Merge. On the other hand, word formation is the result of postsyntactic amalgamation, realized as either Lowering (Embick and Noyer 2001) or its upward counterpart, Raising. This operation, we argue, has properties that are not associated with narrow syntax: it is morphologically driven, it results in word formation, it does not exhibit interpretive effects, and it has stricter locality conditions (the Head Movement Constraint). The result is a view of head movement that not only accounts for the empirical differences between the two classes of head movement phenomena, but also lays to rest numerous perennial theoretical problems that have heretofore been associated with the syntactic head adjunction view of head movement. In addition, the framework developed here yields interesting new predictions with respect to the expected typology of head movement patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although Matushansky (2006) presents arguments for the separability of the two operations (m-merger without syntactic movement and syntactic movement without m-merger), the cases in which this holds do not align with the distinction we advocate here—namely, the separation between head displacement and word formation, each with its own set of characteristic properties.

This can be viewed as a violation of the No Tampering Condition (Chomsky 2008), according to which Merge cannot change the objects it applies to, neither breaking them up nor adding features to them.

We refer here to the PF branch of the Y-model, which in Distributed Morphology (Embick and Noyer 2001) involves a number of possible postsyntactic operations, the application of which ultimately leads to a phonological output. In this way of understanding the interface between syntactic structure and phonological form, the part of the PF branch where most of the action occurs in our proposal is between the output of syntax and the insertion of phonological exponents (Vocabulary Insertion).

As discussed in Sect. 1, our primary goal is to provide empirical and theoretical arguments for a separation of the two head movement types. We make the choice here to implement these two types in terms of syntactic movement and postsyntactic amalgamation within a Distributed Morphology model of the PF interface. It should be noted, however, that the broader arguments are in principle consistent with an alternative view in which the two types of head movement involve, for example, composition in a generative lexicon and syntactic movement. We leave it to future work to tease out any differing predictions made by such alternative implementations. Thanks to David Pesetsky and Paul Kiparsky for discussion of this point.

Our use of the terms raising and lowering at this stage in the discussion is descriptive: raising or lowering of X means the pronunciation of X in a higher or lower position than X’s base position in the syntax.

In the case of Danish, although the evidence indicates that the locus of pronunciation is below T, there is some question as to whether v or V is the target. As Gribanova and Mikkelsen (2018) point out, making the locus v will make the correct predictions with respect to word order in double object constructions, assuming that both objects are introduced inside VP. Here, we maintain, primarily for expository purposes, that the locus of pronunciation is V. If, however, it turns out that there is strong evidence for it being v, this does not affect our overall proposal. What we expect is that there should exist languages in which V is indeed the lowest point of pronunciation; it is possible that Kiowa or one of the other languages in our short list will make a good candidate.

It is important to point out that neither genuine syntactic head movement nor postsyntatic amalgamation are linked to particular domains in an extended projection. The aforementioned Irish case is an example of morphological amalgamation in the C domain, while participle fronting in Bulgarian, discussed in Sect. 2.3, is an example of genuinely syntactic head movement that targets the T domain (see Harizanov 2016 for relevant arguments). We thank a reviewer for raising the important issue of proper double dissociation between the type of head movement observed and its locus of realization.

Negation is written as a separate word orthographically but is proclitic on the verb.

The negation test is irrelevant for Russian, since negation is always proclitic on the tensed auxiliary or verb.

Bailyn (1995a, 1995b) takes the coordination to be at the VP level, but this is because that paper predates the adoption of vP in the functional layer of the clause. Following Svenonius 2004, we assume that v hosts the verb’s theme vowel, which determines numerous properties of the verb (among them argument structure, allomorphic selection, etc.). If this is the case, then coordination here takes place by hypothesis at the vP level.

A good portion of the material in this section grew out of discussions with Jim McCloskey. See McCloskey 2016 for further discussion and elaboration.

It is, however, telling that in all of the cases just mentioned above, the movement in question does not involve morphological amalgamation, but rather effects on word order. This is consistent with our hypothesis, in that, if a movement is syntactic, it is natural for it to be triggered by a featurally encoded head; this encoding may, in some cases, include discourse or illocutionary force features.

As a reviewer points out, the difference in interpretation could, in principle, be instead the result of the subject raising in (19a) but not (19b), with the verb begin staying put in both examples. If this is the right analysis, it would cast doubt on the overall claim that the verb movement is doing the semantic work here and the Shupamem examples would not be an instance of semantically active head movement. For discussion of this alternative approach, see Szabolcsi 2011, Sect. 3.2.1.

This requires Heim’s (1997) ban on meaningless co-indexation, which ensures that the free variable in the antecedent and elided constituent are not accidentally co-indexed.

There is evidence that the verb clustering long passives result in the elimination of an intonational break that would otherwise be there (Wurmbrand 2001:295ff). This, however, is not the same as being part of the same morphological word. See Harizanov 2018 for discussion of morphological vs. phonological wordhood.

See Sect. 3 for a slight modification of this definition, which nevertheless retains the restriction that results in hmc effects.

It is possible that verb-second clauses in other Germanic languages also involve genuinely syntactic head movement, but that it has the appearance of a more local, hmc-obeying movement. For example, T-to-C movement in English questions appears to obey the hmc, but that might be because C happens to attract T, which is the head of C’s complement. Thus, it is possible to maintain that T-to-C in English is of the genuinely syntactic type of head movement and that it is accidental that the interacting heads are in the local relation prescribed by the hmc. A similar question arises for Danish (discussed below and in Sect. 4.1.2), where it is the highest verbal element that undergoes movement to the C domain in root clauses. As a reviewer points out, in traditional approaches to head movement, this is accounted for by the hmc. Within the present approach, such cases must be the result of a relativized minimality constraint on the movement of the verbal element that is highest in the clausal structure in terms of c-command (this issue is further discussed in Sect. 4.1.2). This is accommodated by our proposal, which allows but does not require syntactic head movement to skip heads.

As mentioned in fn. 7, it may be the case that the locus of pronunciation in Danish is v, not V. Nothing in our proposal hinges on this being the case; to adopt this alternative analysis, the system we propose will require postsyntactic lowering of T into v, postsyntactic raising of V into v, and syntactic movement of v to C in V2 environments.

We leave to future work the possibility that this state of affairs could be streamlined further—i.e., that there is a single operation, Amalgamate, which does all of the relevant work. Existing implementations of this general idea include Brody’s (2000) Mirror Theory, and Svenonius’ recent application thereof in combination with the concept of spans (Svenonius 2016, 2018).

Similar ideas can be found in Roberts 2010 and Rizzi and Roberts 1989, though implementations differ. We leave it to future work to sort out differences between our implementation and those of others, which may potentially have similar empirical coverage (Hale and Keyser 2002; Brody 2000; Adger 2013; Hall 2015; Svenonius 2016, among others). The crucial point we make here, which is not shared by many of these approaches (except potentially Adger 2016), is that there exists a principled distinction between the mechanism responsible for morphological unification (amalgamation, or “roll-up” head movement) and the mechanism responsible for displacement in the syntax (Internal Merge). There are other differences too, however. For example, unlike amalgamation, Hale and Keyser’s (2002) “conflation” operation manipulates phonological features rather than morphosyntactic terminals and, in turn, predicts that the units formed by conflation do not have complex internal morphosyntactic structure. To the extent that there is robust evidence for word-internal morphosyntactic structure, this appears to be an undesirable prediction.

The observation that the complex head is pronounced at variable points in the extended projection is also incorporated in the accounts of Brody (2000) and Svenonius (2016, 2018), who specify the locus of pronunciation via features on heads, as we do. We leave to future work the question of whether implementational differences among these accounts will lead to distinct empirical predictions.

We consider it likely that amalgamation is also subject to an absolute locality constraint to the effect that amalgamation cannot apply to heads across the boundary of an extended projection. See Sect. 4.2 for discussion.

We take it that Lowering and Raising into structurally complex specifiers and adjuncts is prohibited by the island status of specifiers and adjuncts.

We assume this for completeness, but leave open the possibility that certain last-resort mechanisms may come into effect in such circumstances, subject to crosslinguistic parameterization.

It might be tempting to analyze the interaction between T and V in English, whereby a bound tense affix appears to lower to the main verb (i.e., “Affix Hopping”), as an instance of amalgamation. In particular, T can be viewed as Lowering into the head of its VP complement:

-

(i)

They enter+ed the room.

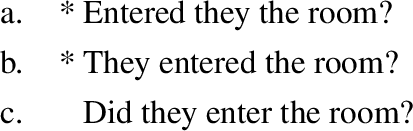

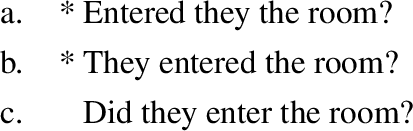

There appears to be evidence against an amalgamation analysis of Affix Hopping, however. Affix Hopping and amalgamation are subject to distinct locality constraints: Affix Hopping is known to be sensitive to the presence of overt specifiers, while amalgamation is not. For example, Affix Hopping fails to unify a main verb and a T that has undergone movement to C (in which case ‘do’-support emerges), as demonstrated in (ii). In (iic), the subject intervenes between T (which occupies a derived position higher than the subject) and V, but there is no intervening head.

-

(ii)

Amalgamation, on the other hand, is only sensitive to intervening heads but not any intervening specifiers (or adjuncts). This suggests that whatever mechanism is responsible for unifying T and main verbs in English (e.g., Merger Under Adjacency; see Bobaljik 2002 and Harley 2013b) is distinct from amalgamation.

-

(i)

As discussed in the main text above, the distribution of the values of the [m] feature is a matter of lexical specification and is, thus, language-specific. In other words, a lexical item can be specified as either containing [m] with a particular value or not. It follows from this that only specifications that lead to convergence would be actually attested.

We leave for future work the possibility of deriving this part of the definition of Raising and Lowering and, thus, the relative locality constraint that amalgamation is subject to, from some deeper property of the PF component of grammar. See also fn. 26.

As a reviewer points out, the proposal that syntactic movement of a head can target a specifier position is incompatible with Chain Uniformity: “A chain is uniform with regard to phrase structure status” (Chomsky 1995b:253). For further discussion, see Fukui and Takano 1998, Toyoshima 2001, Matushansky 2006, Vicente 2007, Harizanov 2016. We take it that removing the Chain Uniformity stipulation is, in general, desirable but recognize that the empirical effects that necessitated it in the first place need to be explained in different and hopefully more basic and principled ways.

Harizanov (2017) explores and empirically motivates an approach to syntactic head movement whereby both options—head movement to a specifier position and reprojective head movement—are instantiated.

Further questions arise about the triggering mechanisms involved in reprojective head movement, which are discussed in detail in the rich literature on reprojection (e.g., Koeneman 2000; Fanselow 2003, 2009; Surányi 2005; Donati 2006; Donati and Cecchetto 2011). We thank a reviewer for raising these important questions about the triggering mechanisms involved in syntactic movement.

Since this scenario involves attraction of a head by a probe, it only concerns head movement to a specifier position rather than reprojective head movement.

We limit the discussion here to one-step movements (i.e., movement chains with two links only). Everything that we say can be extended trivially to multi-step movement and movement chains composed of more than one link. We also represent distinct occurrences of a single syntactic object in the structure using multidominance. This is an expository choice that emphasizes the fact that we are dealing with a single syntactic object occupying distinct structural positions, but other implementations are possible as well. Finally, we remain agnostic here as to whether the movement of Y is an instance of movement to a specifier position or reprojective movement (see the main text above for discussion).

Not all postsyntactic operations need behave in the same way as amalgamation. For example, a reviewer points out that Van Urk’s (2015, 2018) treatment of DP doubling by a pronoun in Dinka is the result of partial deletion of one occurrence of a DP accompanied by nondeletion of another occurrence of the same DP. This is then a case where Chain Reduction, which is responsible for deletion of occurrences to varying degrees, must not affect all occurrences equally and/or in the same way. This state of affairs is consistent with a view of the PF branch of grammar where some operations (such as amalgamation) manipulate the syntactic object associated with multiple structural positions directly, while others (such as linearization and Chain Reduction) manipulate the actual positions that a particular syntactic object is associated with or the phonological content associated with those positions. It is conceivable that the former type of operation applies at an earlier stage of PF than the latter type of operation, but we leave this and other intriguing related questions open at this point.

Note that Lowering and Raising must derivationally precede Chain Reduction. There is independent evidence on the basis of verb doubling in Russian that this is the relative timing of amalgamation and Chain Reduction (Harizanov and Gribanova 2017).

Under the circumstances described above, what we expect is that multiple occurrences should be identical as far as the part of PF between the output of syntax and Vocabulary Insertion is concerned. This is separate from the mechanisms that govern how those occurrences will be realized phonologically, if there is doubling. There is ample evidence that phrasal movement may yield pronunciation of more than one copy, and it is well known that copies under these circumstances may or may not be segmentally identical. Given this, all we are committed to here is that the processes governing spellout of multiple copies in the case of phrasal movement should be in force in the cases we are interested in here. As we elaborate here and in Sect. 4.1.4, however, the relevant kinds of configurations do not arise either in Russian or Modern Hebrew predicate clefting.

A reviewer suggests an alternative treatment of head movement that does not rely on Raising/Lowering, according to which head movement is uniformly syntactic. The idea is that head movement applies in the traditional way, involving head-to-head adjunction and obeying hmc, and that it creates multiple copies of the moved head(s). Given this much, different copies can be prioritized for interpretation at each of the interfaces, PF and LF. For example, it is possible that a high occurrence is interpreted at PF (i.e., pronounced) while a low occurrence is interpreted at LF and, in fact, such a derivation yields head movement with no interpretive effects. However, we think that this alternative approach misses a generalization, since it does not necessitate a connection between locality and the absence of interpretive effects—namely, why should the hmc-compliant head movement (for us, word formation) consistently lack interpretive effects while long distance head movement can have interpretive effects?

Two reviewers ask the very interesting question of how our theory can account for the oft observed complementary distribution between verb movement to the C domain and the presence of an overt complementizer. The nature of the account crucially depends on the proper treatment of the genuinely syntactic head movement in the present theoretical context. As suggested in the introduction to Sect. 4, two possibilities—which may in fact coexist—are head movement to a specifier position and reprojective head movement. If V (or T) movement to the C domain is an instance of head movement to a specifier position, no immediate explanation is available of the complementarity between V (or T) movement and the presence of an overt C. On the other hand, a treatment of V (or T) movement to the C domain as reprojective head movement allows for an understanding of this complementarity: in the derivation of a clause in which V (or T) moves and reprojects, there is no independent C head that is ever merged (Fanselow 2003, 2009; Müller 2011). Note, finally, that under the canonical syntactic head adjunction approach, these facts find no explanation, since there is no inherent reason that head movement should be triggered only by a null C but not by an overt one.

If it is T that Lowers to V in German, it must be V that is targeted by the movement to the C domain, as in Danish (see Sect. 4.1.2).

A reviewer suggests that such an account arguably amounts to a conspiracy. Be that as it may, it is worth pointing out in this connection that the traditional account in which V-to-T movement involves movement of V to v and then of v to T, likewise appears to involve a conspiracy. Specifically, as pointed out by Müller (2011) in a slightly different context, according to this account T attracts v (not V) and only v attracts V, so that the existence of full V-to-T movement emerges as a “fortunate coincidence” (ibid.).

If the clause contains multiple verbal elements, such as auxiliaries, in addition to the main verb, it is the highest verbal element that undergoes syntactic movement to the V2 position in Danish. If this movement is of the reprojective kind, as suggested in fn. 44 and by Fanselow (2003, 2009) and Müller (2011), among others, the fact that the highest verbal element moves can be derived as follows. Assume with Müller (2011) that a verb can be optionally endowed with the feature that triggers reprojective movement and that, in this case, this feature triggers Internal Merge of a verb with TP. Given this, it is the closest verb to TP in terms of c-command (i.e., the highest one) that gets to undergo this movement. If the lower of two verbs is specified for the relevant feature but the higher one is not, the higher verb still acts as a defective intervener in that it blocks the movement of the lower verb but it cannot itself move, resulting in a crash (since the movement triggering feature on the lower verb cannot be satisfied in such a configuration).

The evidence in favor of this claim may be quite subtle, and we do not elaborate on the distinction here. If the distinction between German and Danish non-V2 clauses collapses empirically, then both languages should receive roughly the same analysis, namely the one we present here for Danish.

The unstressed, clause-initial da particle is a discourse particle, orthographically identical to (but semantically distinct from) the stressed particle that means “yes”.

Evidence that the movement is, indeed, syntactic, comes from the observation that this movement step triggers MaxElide effects in Russian verb-stranding ellipsis (Gribanova 2017a).

There is a some variability across languages with respect to the degree to which the two verbal elements in a predicate cleft pattern must match. Harbour (1999) makes clear that the analogous pattern in Classical Hebrew makes possible a greater degree of mismatch than Modern Hebrew; this includes mismatches in the derivational (voice) morphology. Classical Hebrew is of further relevance to us for the way in which it apparently involves a nontrivial interaction between what appears to be syntactic and postsyntactic head movement (Harbour 2007). A proper investigation of these very important patterns will have to be left for another time.

Alternatively, Landau (2006) proposes that the occurrence of V in Spec,TopP is pronounced because it “is associated with a phonological requirement imposed by Top0, namely, the characteristic intonation of fronted VPs.”

As pointed out to us by Daniel Harbour (p.c.), this same explanation cannot hold of predicate cleft patterns in Classical Hebrew, where present tense participles bear no tense morphology, but are nevertheless doubled (Harbour 2007). We leave the very interesting question of what motivates doubling in this case for a separate investigation.

2 and 3 above are language-specific parameters having to do with the featural content of particular lexical items (as far as amalgamation is concerned) and particular facts about how Chain Reduction operates in any given language. 1, on the other hand, simply concerns the particular derivation and how many movements have taken place. The four options above result in 2×2×\(n^{2}\) derivations involving just 2 heads, one of which is the syntactically moved head. If there are multiple (i.e., >1) heads that amalgamate with the syntactically moved one, there will be additional possible outcomes. The particular formulation of amalgamation in Sect. 3 predicts only a subset of all imaginable outcomes to be possible—see below for further discussion.

Given that there are instances of amalgamation in Danish and Russian which appear to cross the vP boundary and that vP has been argued to be a phase at least in some languages, the question arises as to how to understand the relevant facts in Danish and Russian. One possibility, which is in principle empirically distinguishable from the alternative, is that vP is not a phase in these languages and that is why amalgamation is able to apply across the vP boundary. In fact, we know of no positive evidence to the contrary. If, on the other hand, vP is a phase in Danish and Russian, that might indicate that the relevant locality domain for amalgamation is the extended projection, rather than the phase. In turn, this would mean that amalgamation cannot cross DP and CP boundaries, as required by the empirical facts.

Incidentally, there are many putatively syntactic movements (e.g., most A-movements) that are clause-bounded (i.e., they cannot cross finite clause boundaries). Therefore, the clause-boundedness of some instance of displacement cannot by itself lead to the conclusion that this displacement is not syntactic. As expected, then, some syntactic head movements (e.g., Danish V-to-C) are clause-bounded while others (Bulgarian and Hebrew long head movement) are unbounded.

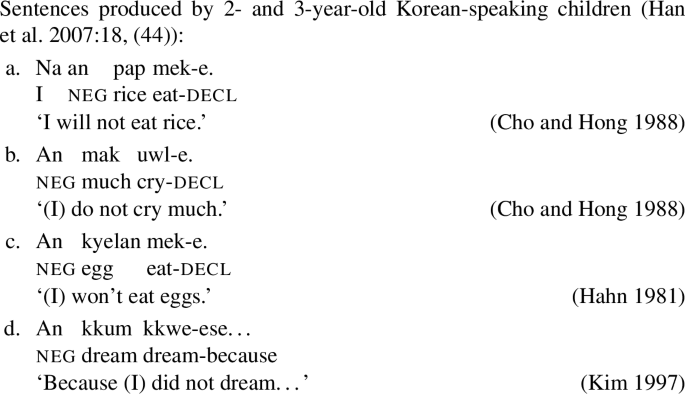

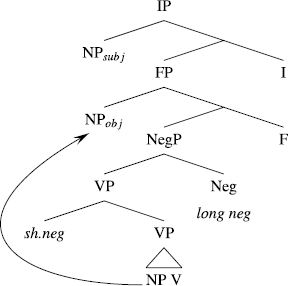

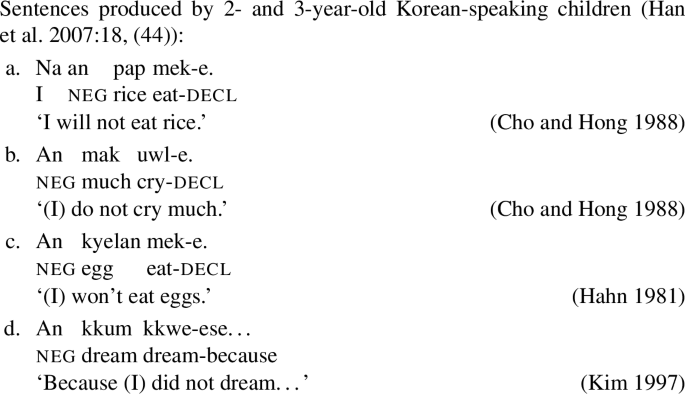

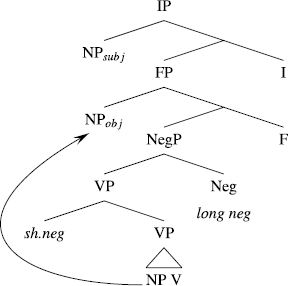

It is well known that Korean also has a type of negation called long negation, and the two forms may co-occur. Han et al. (2007) further make the case that short negation is most likely an adjunct, or (less likely) it is the head of a lower Neg projection (where long negation is housed in a higher Neg projection).

We put aside, for the moment, the difficulty that short negation is hosted in an adjunct position, and the traditional understanding of head movement will not permit movement through an adjunct position.

As with English, there is an open question as to how the negation can scope over the object since, with a head-adjunction approach, it will be too deeply embedded in the complex head. See the latter part of this section for discussion of this issue.

A reviewer expresses the concern that making available variable positions for negation across languages may invalidate numerous other arguments with respect to verb movement and the relative position of verbs with negation. The language-specific situation in Korean, though, speaks to the necessity of such a move: there are already two ways to expone different types of negation, long and short; Han et al.’s (2007) structure has short negation as an adjunct, making it more likely, at least in principle, that there might be different adjunction sites in the structure. The idea that all languages project negation in the same position in the extended projection is an interesting theoretical stance, but it seems to us that the jury is out about the degree to which it is consistent with existing typological surveys. What is important is that acquirers (in the default case) get quite a bit of convergent evidence about the position of negation in their language. The hypothesis we put forth here about Korean—that speakers may make different conclusions about the relative height of negation—is possible because Korean is a right-headed language with a short negation that is projected on the left, leaving little overt evidence for its position. The data from earlier stages of acquisition seems to confirm this. In essence, we are making the point that Han et al.’s argument about the absence of strong evidence with respect to the position of the verb may apply equally well to the position of short negation. The ambiguity is far less likely to arise in left-headed languages, i.e., French.

There is an additional question as to how the negation comes to be a part of the rest of the complex. Han et al. (2007) indicate that the composition is via head movement, at least in the case of short negation—but this will only work if short negation is the exponent of a head in the clausal spine, not an adjunct. Since the question does not bear directly on the two alternatives outlined here, in that regardless of what the relevant process is, it should not affect scope, we will leave this as an open question for the moment.

If T to C is an instance of syntactic head movement as reprojection, as we suggest in Sect. 4, then the T with negative features will also c-command the NPI directly from its raised position. This is an improvement over the standard head movement qua head adjunction account, since in that account—as pointed out by Hall (2015)—the head-moved negation will be too deeply embedded to c-command the NPI it is supposed to license.

A reviewer points out that another argument for the semantic potency of T-to-C movement with contracted negation comes from Romero and Han 2004 and Romero 2005, who argue that the raising of negation to a higher position is what affects the interpretation of polar questions in English, yielding Ladd’s ambiguity (Ladd 1981).

References

Abels, Klaus. 2003a. Auxiliary adverb word order revisited. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 9 (1).

Abels, Klaus. 2003b. Successive cyclicity, anti-locality, and adposition stranding. PhD diss., University of Connecticut.

Adger, David. 2013. A syntax of substance. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Adger, David. 2016. Baggett Lecture 1: A Menagerie of Merges. Talk presented at the University of Maryland, February 2016.

Adger, David, Daniel Harbour, and Laurel Watkins. 2009. Mirrors and microparameters: Phrase structure beyond free word order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ahn, Byron. 2015. Giving reflexivity a voice: Twin reflexives in English. PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Aissen, Judith. 1974. Verb raising. Linguistic Inquiry 5 (3): 325–366.

Arregi, Karlos, and Asia Pietraszko. 2018. Generalized head movement. Proceedings of the Linguistics Society of America Annual Meeting 3 (4): 1–15.

Bailyn, John Frederick. 1995a. A configurational approach to Russian ‘free’ word order. PhD diss., Cornell University.

Bailyn, John Frederick. 1995b. Underlying phrase structure and ‘short’ verb movement in Russian. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 3 (1): 13–58.

Baker, Mark. 1985. The mirror principle and morphosyntactic explanation. Linguistic Inquiry 16: 373–415.

Baker, Mark C. 1988. Incorporation: A theory of grammatical function changing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Benedicto, Elena. 1998. Verb movement and its effects on determinerless plural subjects. In Romance linguistics: Theoretical perspectives, eds. Armin Schwegler, Bernard Tranel, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria, 25–40. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bennett, Ryan, Emily Elfner, and James McCloskey. To appear. Prosody, focus and ellipsis in Irish. Language.

Biberauer, Theresa, and Ian Roberts. 2010. Subjects, tense and verb-movement in Germanic and Romance. In Parametric variation: Null subjects in minimalist theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2002. A-chains at the PF-interface: Copies and ‘covert’ movement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 20 (2): 197–267.

Borsley, Robert D., and Andreas Kathol. 2000. Breton as a V2 language. Linguistics 38 (4): 665–710.

Bowers, John. 1993. The syntax of predication. Linguistic Inquiry 24 (4): 591–656.

Brody, Michael. 2000. Mirror theory: Syntactic representation in perfect syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 31 (1): 29–56.

Broekhuis, Hans, and Krzysztof Migdalski. 2003. Participle fronting in Bulgarian. Linguistics in the Netherlands 20: 1–12.

Cable, Seth. 2012. Pied-piping: Introducing two recent approaches. Language and Linguistics Compass 6 (12): 816–832.

Cho, Young-Mee Yu, and Ki-Sun Hong. 1988. Evidence for the VP constituent from child Korean. In Papers and reports on child language development 27, 31–38. Stanford: Stanford University Department of Linguistics.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995a. Bare phrase structure. In Government and binding theory and the minimalist program, ed. Gert Webelhuth, 383–439. Cambridge: Blackwell Sci.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995b. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta. Cambridge: MIT Press.

den Besten, Hans. 1983. On the interaction of root transformations and lexical deletive rules. In On the formal syntax of the Westgermania, ed. Werner Abraham, 47–131. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Donati, Caterina. 2006. On wh-head movement. In Wh-movement: Moving on, eds. Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng and Norbert Corver, 21–46. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Donati, Caterina, and Carlo Cecchetto. 2011. Relabeling heads: A unified account for relativization structures. Linguistic Inquiry 42 (4): 519–560.

Duffield, Nigel. 1993. On case-checking and NPI licensing in Hiberno-English. Rivista Di Linguistica 7: 215–244.

Embick, David, and Roumyana Izvorski. 1997. Participle-auxiliary word orders in Slavic. In Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL): The Cornell Meeting 1995, eds. Natasha Kondrashova, Wayles Browne, Ewa Dornisch, and Draga Zec, Vol. 4, 210–239. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Embick, David, and Rolf Noyer. 2001. Movement operations after syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 32: 555–595.

Fanselow, Gisbert. 2003. Münchhausen-style head movement and the analysis of verb second. UCLA Working Papers in Linguistics 13: 40–76.

Fanselow, Gisbert. 2009. Bootstrapping verb movement and the causal architecture of German (and other languages). In Advances in comparative Germanic syntax, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Jorge Hankamer, Thomas McFadden, and Justin Nuger, 85–118. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Fauconnier, Gilles. 1975. Pragmatic scales and logical structure. Linguistic Inquiry 6: 353–376.

Fauconnier, Gilles. 1979. Implication reversal in a natural language. In Formal semantics and pragmatics for natural languages, eds. Franz Guenther and Siegfried Schmidt, 289–301. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Filppula, Markku. 1986. Some aspects of Hiberno-English in a Functional Sentence Perspective. University of Joensuu Publications in the Humanities 7.

Filppula, Markku. 1991. From Anglo-Irish to Hiberno-English: divergence and convergence in the Irish dialects of English. In International Congress of Dialectologists, Bamberg, ed. Wolfgang Vierick. Wiesbaden: Frank Steiner Verlag.

Franks, Steven. 2008. Clitic placement, prosody, and the Bulgarian verbal complex. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 16 (1): 91–137.

Fukui, Naoki, and Yuji Takano. 1998. Symmetry in syntax: Merge and demerge. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 7 (1): 27–86.

Georgi, Doreen, and Gereon Müller. 2010. Noun-phrase structure by Re-Projection. Syntax 13 (1): 1–36.

Gribanova, Vera. 2013. Verb-stranding verb phrase ellipsis and the structure of the Russian verbal complex. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31 (1): 91–136.

Gribanova, Vera. 2017a. Head movement and ellipsis in the expression of Russian polarity focus. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 35 (4): 1079–1121.

Gribanova, Vera. 2017b. Head movement, ellipsis, and identity. Ms., Stanford University.

Gribanova, Vera, and Line Mikkelsen. 2018. In A Reasonable Way to Proceed: Essays in Honor of Jim McCloskey, eds. Jason Merchant, Line Mikkelsen, Deniz Rudin, and Kelsey Sasaki, 105–124. UC eScholarship Repository.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1991. Extended projection. Ms., Brandeis University.

Grohmann, Kleanthes K. 2003. Prolific domains: On the anti-locality of movement dependencies. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Hagstrom, Paul. 2000. Phrasal movement in Korean negation. In Student Conference in Linguistics (SCIL) 9, eds. Ljuba Veselinova, Susan Robinson, and Lamont Antieau, 127–142. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Hagstrom, Paul. 2002. Implications of child error for the syntax of negation in Korean. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 11: 211–242.

Hahn, Kyung-Ja Park. 1981. The development of negation in one Korean child. PhD diss., University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Haider, Hubert. 2010. The syntax of German. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hale, Ken, and Samuel Jay Keyser. 2002. Prolegomenon to a theory of argument structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hall, David. 2015. Spelling out the noun phrase: Interpretation, word order, and the problem of ‘meaningless movement’. PhD diss., Queen Mary University of London.

Han, Chung-hye, and Laural Siegel. 1997. Syntactic and semantic conditions on NPI licensing in questions. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 15, eds. Brian Agbayani and Sze-Wing Tang. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Han, Chung-hye, Jeffrey Lidz, and Julien Musolino. 2007. V-raising and grammar competition in Korean: Evidence from negation and quantifier scope. Linguistic Inquiry 38 (1): 1–47.

Han, Chung-hye, Jeffrey Lidz, and Julien Musolino. 2016. Endogenous sources of variation in language acquisition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113 (4): 942–947.

Harbour, Daniel. 1999. The two types of predicate clefts: Classical Hebrew and beyond. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Harbour, Daniel. 2007. Beyond PersonP. Syntax 3 (10): 223–242.

Harizanov, Boris. 2014. Clitic doubling at the syntax-morphophonology interface: A-movement and morphological merger in Bulgarian. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 4 (32): 1033–1088.

Harizanov, Boris. 2016. Head movement to specifier positions in Bulgarian participle fronting. Presented at Linguistic Society of America (LSA 90). Available at https://stanford.edu/~bharizan/pdfs/Harizanov_2016_LSA_handout.pdf. Accessed 16 June 2018.

Harizanov, Boris. 2017. On the nature of syntactic head movement. Colloquium, Department of Linguistics. McGill University, Montréal, Québec.

Harizanov, Boris. 2018. Word formation at the syntax-morphology interface: Denominal adjectives in Bulgarian. Linguistic Inquiry 49 (2): 283–333.

Harizanov, Boris, and Vera Gribanova. 2017. Post-syntactic head movement in Russian predicate fronting. Presented at the Linguistic Society of America (LSA) 91.

Harley, Heidi. 2013a. Diagnosing head movement. In Diagnosing syntax, eds. Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng and Norbert Corver, 112–119. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harley, Heidi. 2013b. Getting morphemes in order: Merger, affixation and head movement. In Diagnosing syntax, eds. Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng and Norbert Corver. London: Oxford University Press.

Harris, John. 1984. Syntactic variation and dialect divergence. Journal of Linguistics 20: 307–327.

Hartman, Jeremy. 2011. The semantic uniformity of traces: Evidence from ellipsis parallelism. Linguistic Inquiry 42 (3): 367–388.

Harves, Stephanie. 2002. Genitive of negation and the syntax of scope. In ConSOLE 9, eds. Marjo van Koppen, Erica Thrift, Eric J. van der Torre, and Malte Zimmerman, 96–110.

Heck, Fabian. 2008. A theory of pied-piping. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Heck, Fabian. 2009. On certain properties of Pied-Piping. Linguistic Inquiry 40 (1): 75–111.

Heim, Irene. 1997. Predicates or formulas? Evidence from ellipsis. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 7, ed. Aaron Lawson, 197–221. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Holmberg, Anders. 1986. Word order and syntactic features in the Scandinavian languages and English. PhD diss., University of Stockholm.

Iatridou, Sabine, and Ivy Sichel. 2011. Negative DPs, A-movement, and scope diminishment. Linguistic Inquiry 42 (2): 595–629.

Iatridou, Sabine, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Roumyana Izvorski. 2001. Some observations about the form and meaning of the perfect. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Izvorski, Roumyana. 2000. Free relatives and related matters. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

Jenks, Peter. 2013. Head movement in Moro DPs: Evidence for a unified theory of movement. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 31, ed. Robert E. Santana-LaBarge, 248–257. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Julien, Marit. 2002. Syntactic heads and word formation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kayne, Richard S. 1991. Romance clitics, Verb movement, and PRO. Linguistic Inquiry 22 (4): 647–686.

Keine, Stefan, and Rajesh Bhatt. 2016. Interpreting verb clusters. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 34 (4): 1445–1492.

Kim, Young-Joo. 1997. The acquisition of Korean. In The crosslinguistic study of language acquisition, vol. 4, ed. Dan I. Slobin, 334–443. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

King, Tracy Holloway. 1995. Configuring topic and focus in Russian. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Koeneman, Olaf. 2000. The flexible nature of verb movement. Utrecht: LOT.

Koopman, Hilda. 1984. The syntax of verbs: From verb-movement rules in the Kru languages to universal grammar. Dordrecht: Foris.

Koopman, Hilda, and Anna Szabolcsi. 2000. Verbal complexes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

LaCara, Nicholas. 2016a. A Germanic verb movement paradox. Presented at the Stanford Workshop on Head Movement, Stanford University.

LaCara, Nicholas. 2016b. Verb phrase movement as a window into head movement. Linguistic Society of America (LSA).

Ladd, Robert D. 1981. A first look at the semantics and pragmatics of negative questions and tag questions. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS 17), 164–171. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Ladusaw, William. 1979. Polarity sensitivity as inherent scope relations. PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin. Published in the Distinguished Dissertations in Linguistics Series, Garland Press.

Ladusaw, William. 1980. On the notion ‘affective’ in the analysis of negative-polarity items. Journal of Linguistic Research 1: 1–16.

Laka, Itziar. 1990. Negation in syntax: On the nature of functional projections in syntax. PhD diss., MIT.

Lambova, Mariana. 2004. On triggers of movement and effects at the interfaces. In Studies in generative grammar, 75: Triggers, eds. Anne Breibarth and Henk C. van Reimsdijk, 231–258. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Landau, Idan. 2002. (Un)interpretable Neg in Comp. Linguistic Inquiry 33: 465–492.

Landau, Idan. 2006. Chain resolution in Hebrew (V)P-fronting. Syntax 9 (1): 32–66.

Larson, Richard. 1988. On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19 (3): 335–391.

Lasnik, Howard. 2001. When can you save a structure by destroying it? In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 31, eds. Min-Joo Kim and Uri Strauss, 301–320. Amherst: GLSA.

Lechner, Winifred. 2007. Interpretive effects of head movement. Ms., University of Athens. Available at http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/000178. Accessed 18 June 2018.

Lema, José, and María Luisa Rivero. 1990. Long head movement: HMC vs. ECP. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 20, ed. Juli A. Carter, 337–347. Amherst: GLSA.

Lightfoot, David. 1991. How to set parameters: Arguments from language change. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lightfoot, David. 1993. Why UG needs a learning theory: Triggering verb movement. In Historical linguistics: Problems and perspectives, ed. Charles Jones, 190–214. London: Longmans.

Linebarger, Marcia C. 1980. The grammar of negative polarity. PhD diss., MIT.

Lipták, Anikó, and Andrés Saab. 2014. No N-raising out of NPs in Spanish: Ellipsis as a diagnostic of head movement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32: 1247–1271.

Matushansky, Ora. 2006. Head movement in linguistic theory. Linguistic Inquiry 1: 69–109.

McCloskey, James. 1996. On the scope of verb raising in Irish. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 14: 47–104.

McCloskey, James. 2012. Polarity, ellipsis and the limits of identity in Irish. Presented at the workshop on Ellipsis, Nanzan University. Available at http://ohlone.ucsc.edu/~jim/PDF/nanzan-handout.pdf. Accessed 16 June 2018.

McCloskey, James. 2016. Interpretation and the typology of head-movement: A re-assessment. Talk presented at the workshop on the status of head movement in linguistic theory, Stanford University.

McCloskey, James. 2017. Ellipsis, polarity and the cartography of verb-initial orders in Irish. In Elements of comparative syntax: Theory and description, eds. Enoch Aboh, Eric Haeberli, Genoveva Puskás, and Manuela Schönenberger, 99–151. Berlin: De Gruyter.

McPherson, Laura. 2014. Replacive grammatical tone in the Dogon languages. PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Merchant, Jason. 2008. Variable island repair under ellipsis. In Topics in ellipsis, ed. Kyle Johnson, 132–153. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Messick, Troy, and Gary Thoms. 2016. Ellipsis, economy and the (non)uniformity of traces. Linguistic Inquiry 47 (2): 306–332.

Mikkelsen, Line. 2015. VP anaphora and verb-second order in Danish. Journal of Linguistics 51 (3): 595–643.

Müller, Gereon. 2011. Constraints on displacement: A phase-based approach. Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Nicolae, Andreea C. 2013. Any questions? Polarity as a window into the structure of questions. PhD diss., Harvard University.

Nicolae, Andreea C. 2015. Questions with NPIs. Natural Language Semantics 23: 21–76.

Ostrove, Jason. 2015. Allomorphy and the Irish verbal complex. UC Santa Cruz. Available at https://people.ucsc.edu/~jostrove/QP1.pdf. Accessed 16 June 2018.

Ostrove, Jason. 2016. Mixtec syntax and morphology. Ms., UC Santa Cruz.

Penka, Doris. 2002. Zur Semantik der negativen Indefinita im Deutschen. Universität Tübingen: Tübingen-Linguistik-Report Nr. 1.

Penka, Doris, and Arnim von Stechow. 2001. Negative indefinita unter Modalverben. In Modalität und Modalverben im Deutschen, eds. Reimar Müller and Marga Reis, 263–286. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

Pesetsky, David, and Esther Torrego. 2001. T-to-C movement: Causes and consequences. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 355–426. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Pietraszko, Asia. To appear. Relative clauses and CP nominalization in Ndebele. Syntax.

Platzack, Christer. 2013. Head movement as a phonological operation. In Diagnosing syntax, eds. Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng and Norbert Corver, 21–43. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1989. Verb movement, universal grammar, and the structure of IP. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 365–424.

Preminger, Omer. To appear. What the PCC tells us about “abstract” agreement, head movement, and locality. Glossa.

Progovac, Ljiljana. 1993. Negative polarity: Entailment and binding. Linguistics and Philosophy 16: 149–180.

Richards, Norvin. 1998. The principle of minimal compliance. Linguistic Inquiry 29 (4): 599–629.

Rivero, Maria-Luisa. 1991. Long head movement and negation: Serbo-Croatian vs. Slovak and Czech. The Linguistic Review 8: 319–351.

Rivero, María Luisa. 1992. Patterns of V0-raising in long head movement and negation: Serbo-Croatian vs. Slovak. In Syntactic theory and Basque syntax, eds. Joseba Andoni Lakarra and Jon Ortiz de Urbina, 365–386. Gipuzkoa: Gipuzkoako Foru Aldundia.

Rivero, Maria-Luisa. 1994. Clause structure and V-movement in the languages of the Balkans. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 12: 62–120.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1990. Relativized minimality. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rizzi, Luigi, and Ian Roberts. 1989. Complex inversion in French. Probus 1 (1): 1–30.

Roberts, Ian. 1991a. Excorporation and minimality. Linguistic Inquiry 22 (1): 209–218.

Roberts, Ian. 1991b. Head-government and the local nature of head-movement. Glow Newsletter 26.

Roberts, Ian. 1994. Two types of head movement in Romance. In Verb movement, eds. David Lightfoot and Norbert Hornstein, 207–242. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, Ian. 2010. Agreement and head movement: Clitics, incorporation, and defective goals. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rohrbacher, Bernhard. 1994. The Germanic VO languages and the full paradigm: A theory of V to I raising. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Romero, Maribel. 2005. Two approaches to biased yes/no questions. In Proceedings of the 24th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, 352–360. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Romero, Maribel, and Chung-Hye Han. 2004. On negative yes/no questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 27 (27): 609–658.

Schafer, Robin. 1995. Negation and verb second in Breton. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 13 (1): 135–172.

Schoorlemmer, Erik, and Tanja Temmerman. 2012. Head movement as a PF-phenomenon: evidence from identity under ellipsis. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 29, eds. Jaehoon Choi, E. Alan Hogue, Jeffrey Punske, Deniz Tat, Jessamyn Schertz, and Alex Trueman, 232–240. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1995. Sentence prosody: Intonation, stress and phrasing. In The handbook of phonological theory, ed. John A. Goldsmith. London: Blackwell Sci.

Surányi, Balázs. 2005. Head movement and reprojection. Annales Universitatis Scientiarum Budapestinensis de Rolando Eötvös Nominatae. Sectio Linguistica. ELTE Tomus 26: 313–342.

Svenonius, Peter. 2004. Slavic prefixes and morphology: An introduction to the Nordlyd volume. Nordlyd 32 (2): 177–204.

Svenonius, Peter. 2016. Spans and words. In Morphological metatheory, eds. Daniel Siddiqi and Heidi Harley, 201–222. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Svenonius, Peter. 2018. Delimiting the syntactic word. Presented at Linguistics at Santa Cruz.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 2011. Certain verbs are syntactically explicit quantifiers. In Formal semantics and pragmatics: Discourse, context, and models. Vol. 6 of The Baltic international yearbook of cognition, logic and communication.

Takahashi, Shoichi, and Danny Fox. 2005. MaxElide and the re-binding problem. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 15, eds. Effi Georgala and Jonathan Howell, 223–240. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Toyoshima, Takashi. 2001. Head-to-spec movement. In The minimalist parameter, eds. Galina M. Alexandrova and Olga Arnaudova, 115–136. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Travis, Lisa. 1984. Parameters and effects of word order variation. PhD diss., MIT.

van Urk, Coppe. 2015. A uniform syntax for phrasal movement: A Dinka Bor case study. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

van Urk, Coppe. 2018. Pronoun copying in Dinka and the Copy Theory of Movement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory.

Vicente, Luis. 2007. The syntax of heads and phrases: A study of verb (phrase) fronting. PhD diss., Leiden University.

Vikner, Sten. 1995. Verb movement and expletive subjects in the Germanic languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

von Stechow, Arnim. 1993. Die Aufgaben der Syntax. In Ein internationales Hadbuch zeitgenossischer Forschung, eds. Arnim von Stechow and Theo Vennemann, 1–88. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Wechsler, Stephen. 1991. Verb second and illocutionary force. In Views on phrase structure, eds. Katherine Leffel and Denis Bouchard, 177–191. The Netherlands: Springer.

Wiklund, Anna-Lena. 2010. In search of the force of dependent verb second. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 33 (1): 81–91.

Wilder, Chris, and Damir Cavar. 1994. Word order variation, verb movement, and economy principles. Studia Linguistica 48: 46–86.

Wurmbrand, Susi. 2001. Infinitives: Restructuring and clause structure. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Zwicky, Arnold, and Geoff Pullum. 1983. Cliticisation vs. inflection: English n’t. Language 59: 502–513.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following colleagues for helpful comments and feedback on this work: Klaus Abels, David Adger, Karlos Arregi, Rajesh Bhatt, Lauren Eby Clemens, Sandra Chung, Güliz Güneş, Heidi Harley, Peter Jenks, Paul Kiparsky, Nicholas LaCara, Beth Levin, Line Mikkelsen, Paul Kiparsky, Anikó Lipták, David Pesetsky, Omer Preminger, Ian Roberts, Peter Svenonius, Lisa Travis, and audiences at FDSL 12, Leiden University, the McGill Word Structure research group, and the 91st annual LSA meeting in Austin, TX. Conversations with Jim McCloskey over the course of about two years have been crucial to this paper’s development. We thank him especially for all of these exchanges, and for letting us steal the paper’s title from an old handout of his. Finally, we are grateful to Daniel Harbour and three NLLT reviewers for detailed comments and constructive criticism. All errors are the authors’ responsibility alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Harizanov and Gribanova are co-first authors of this paper.

Only syntactic head movement yields interpretive effects

Only syntactic head movement yields interpretive effects

In Sect. 2.2, we demonstrated that for the available case studies on any potential interpretive effects of head movement, the movement in question is the kind which our proposal would take to be syntactic. We know of three putative exceptions to this pattern: head movement in Korean (Han et al. 2007), English NPI licensing by head-moved negation (Ladusaw 1979, 1980; McCloskey 1996), and DP interpretation relative to verb position in Spanish (Benedicto 1998). All three are putative exceptions to our generalization in Sect. 2.2, because the head movement in all three cases appears to be the inflection-driven type, and it results in the building of a morphophonological complex. This is the type of head movement that we propose is postsyntactic in nature, and therefore we predict that interpretive effects related to this kind of head movement should not exist. We cover the Korean and English cases in detail below, arguing that there is an alternative explanation for the attested patterns. Space considerations prevent us from implementing a detailed discussion of Benedicto’s proposal here; fortunately, we can refer to Hall 2015:106–117 for a summary of Benedicto’s arguments and an in-depth counter-argument.

1.1 A.1 Korean verb raising and the scope of negation

The first case we consider in detail is Han et al.’s (2007) of Korean verb raising, in which it is demonstrated experimentally that within the population of Korean speakers there are actually two distinct grammars—one in which the verb is raised, and one in which it is not. The group that interests us is the one whose grammar makes use of verb raising; this is because the primary evidence for this raising comes from the scope interactions between negation (attached to the verb) and a quantified DP in its surface position (Korean is a surface scope language). If head movement of the so-called short negation particle (along with the rest of the verbal complex) results in a difference in scope-taking possibilities with respect to a quantified object, then this is an interpretive consequence that is associated with amalgamation-type head movement—a result our theory predicts should not exist.

The argument consists of several components. First, the authors take the stance, along with Hagstrom (2000, 2002), that objects move from their base positions into a higher position, outside of VP. They also assume that short negation (the type of negation that is of interest to us here) is adjoined to VP, so that the surface position of the object is higher than the initial position of the negative particle.Footnote 57

-

(69)

Given this kind of a structure, the reasoning is that if a verb moves up the tree to a position higher than the position that hosts object shift, the negation (which is pied-piped along) will be able to scope above the quantified object.Footnote 58 What Han et al. demonstrate is that a portion of the population they tested does indeed get the reading in which the negation scopes higher than the quantified object—this, for them, leads to the conclusion that the verb has undergone movement, pied-piping negation along, to a high position.Footnote 59

There are, however, at least two entirely different analyses which Han et al. do not consider, but which require no verb movement and still account for the relevant facts. On one of these analyses, the population for which negation can scope over the quantified object speaks a variant of Korean in which the negation itself may adjoin higher in the structure. The fact that children’s Korean often involves a stage in which the short negation is pronounced separately from the verb seems to support this analysis: in such cases, the negation appears pre-verbally, suggesting that it is merged higher in the structure than the shifted object.

-

(70)

That such a syntactic configuration is possible in a stage of acquisition supports the idea that the scope of negation with respect to the quantified objects may be a consequence of different possibilities with respect to the height of attachment of negation.Footnote 60 If this is the case, we have an alternative understanding of why there may be two grammars among Korean speakers: one subset of the population adjoins the negation lower than the surface position of the object; one subset of the population adjoins it higher than the surface position of the object. If this kind of explanation is viable, the result is that the empirical picture sketched by Han et al. 2007 does not necessitate the conclusion that there is scope-expanding head movement that is of the amalgamation type.

A second alternative, suggested by David Adger (via an anonymous reviewer), is that the object in such configurations may reconstruct to the lower position for some speakers of Korean, yielding a different grammar and therefore a different interpretation for some subset of the population. Scope freezing is shown in Han et al. 2007 between subjects and objects; this means that subject reconstruction must be impossible across the board. But object reconstruction is still consistent with the scope freezing between subjects and objects, and therefore could in theory obtain. This approach has the advantage that it predicts a result from a follow-up study in Han et al. 2016, where the authors demonstrate that speakers treat long and short negation similarly: if they get short negation out-scoping the object, they also get long negation out-scoping the object. This follows from a structure like (71), where short and long negation co-occur as Han et al. (2007) would have them.

-

(71)

The two instances of negation in (71) are quite close to one another, with the result that if the object reconstructs for speakers with one of the possible grammars, it will reconstruct to a position that is beneath both instances of negation.Footnote 61

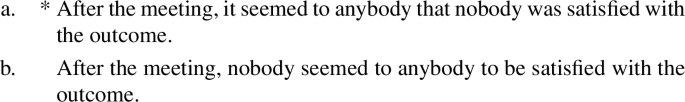

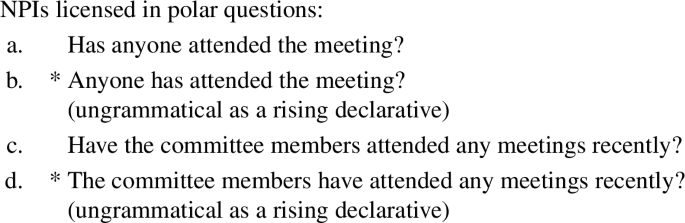

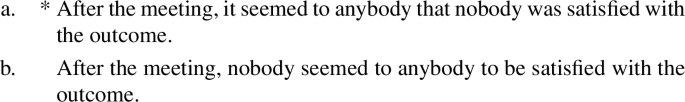

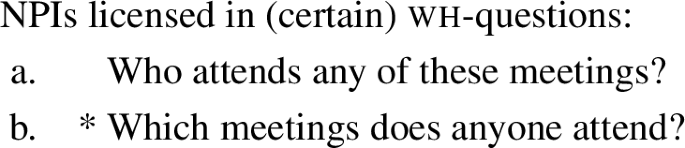

1.2 A.2 English NPI licensing

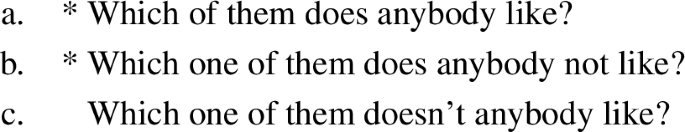

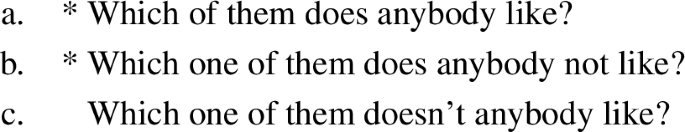

The second paradigm we consider here comes from English, and is an oft-cited case in which it appears that head movement of T to C, pied-piping clitic negation, licenses an otherwise unlicensed negative polarity item (NPI). We start with the basic facts, namely that one way of licensing an NPI in English is to position it so that it is c-commanded by something negative (McCloskey 1996). We see this in the phrasal context in (72), where the NPI anybody is licensed only when nobody undergoes raising and c-commands it from the raised position.

-

(72)

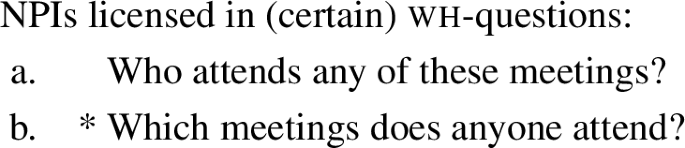

Important for our discussion is that this pattern seems to extend to head movement of negation to a position above the NPI:

-

(73)

(73) demonstrates that negation must be present to license a subject NPI in English (73a), but merely its presence in the clause is not enough (73b); the negation must be raised—via head movement on the traditional analysis—to a position that is higher in the clause than the NPI (73c). To understand why this paradigm bears on our overall argument, let us first consider one way in which the theory proposed here might be made to account for it. On our view, the head movement involved will be of two different types: the movement of T to C will be syntactic, as it involves no word formation; but the unification of the auxiliary or modal in T with negation does result in word formation, and may therefore, at least in theory, be construed as an instance of postsyntactic amalgamation.

Below, we will argue against such an approach; in order to do this, we first sketch how the account would work. As discussed in Sect. 4, the postsyntactic and syntactic types of head movement may interact; in this case, the syntactic component will involve movement of T to C; PF will amalgamate Neg into T, yielding a complex head containing T and Neg. This complex head will be realized in C, in accordance with the English tendency to realize the highest occurrence in a syntactic movement chain.

-

(74)

If what is crucial for the scope effect described just above is the presence of negation in the higher position that licenses the NPI, and if it is postsyntactic amalgamation of Neg into T that is partially responsible for the presence of Neg in the higher position, this instance of amalgamation would have interpretive effects. If this is the correct interpretation of what is going on in (73), then (73) is a counterexample, involving poststynactic amalgamation that—counter to our expectations—feeds the LF interface.

We propose here that there is an alternative explanation for the English NPI licensing paradigm that involves no postsyntactic amalgamation. We think that this alternative is empirically superior, and adopting it will have the consequence that the only head movement yielding an interpretive effect is the movement of T to C—a head movement we would designate as taking place on the syntax. The alternative we wish to put forward here is that what matters for NPI licensing in (73) is the presence of a C head, valued with negative polarity features and c-commanding the relevant NPI. Head movement of T to C (or of Neg to T) is therefore orthogonal to this, and an indirect reflex of the fact that in Standard American English, the C that comes with unvalued polarity features is also the C that triggers T to C.

There are two ways to implement the idea that a C head with negative features is what licenses the subject NPI. One is to claim, with Biberauer and Roberts (2010), that English has both positive and negative auxiliaries, the latter a result of a T that comes with valued negative polarity features, as has been claimed for the Uralic languages, Latin, Old English, and Afrikaans. Evidence for this comes, among other things, from Zwicky and Pullum’s (1983) observation that n’t triggers stem allomorphy (e.g., *will’nt/won’t). On such an approach, the negative auxiliary in T will be raised to C, possibly in conjunction with an agree relation that values unvalued polarity features on C, licensing the NPI directly.Footnote 62 If this is the case, the only head movement involved is T to C, and to the extent that it is even responsible for the NPI licensing, the head movement is not of the kind that leads to word formation—as our proposal would predict.Footnote 63 A second possibility is the one proposed in Roberts 2010 and summarized in Hall 2015, in which both C and T are encoded with unvalued polarity features, while Neg has them valued. T agrees with Neg, and C subsequently agrees with T. Polarity feature valuation or sharing among the C-Pol-T complex receives quite a bit of support crosslinguistically; for analogous proposals, see McCloskey 2017 for Irish; Landau 2002 for Hebrew; and Gribanova 2017a for Russian. As Hall (2015) points out, it is then the presence of a C valued with negative polarity features that is responsible for the NPI licensing; head movement becomes orthogonal to the discussion.

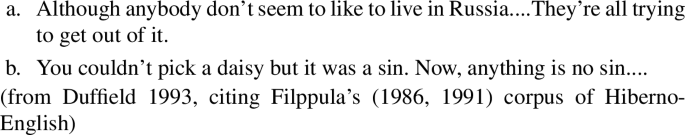

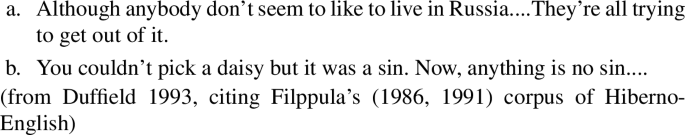

Either approach described above seems empirically superior to an account that relies on head movement of Neg, insofar as it can unify the licensing of subject NPIs in a broader range of environments than can an account in which head movement of Neg is the key. If the unifying observation is that a negatively-valued C is what matters, then we have a way of understanding not just (73), but also two further observations. The first comes from Hiberno-English (Harris 1984; Duffield 1993), in which lower negation also seems to license subject NPIs in declaratives.

-

(75)

If we take the NPI licensing in Hiberno-English to be the result of valuation of C’s unvalued polarity features by a lower negation, the pieces fall into place. The difference between Standard American English and Hiberno-English on this account is whether this kind of C triggers T to C movement. The valuation of C’s polarity features remains the common link between them, and it is the availability of this negative C that licensed the subject NPI in both varieties, not the head movement.

The second empirical argument, originating in Ladusaw 1979, is the observation that NPIs can be licensed in the complement of certain inherently negative predicates, such as unlikely.

-

(76)

It is unlikely that anyone will be appointed.

-

(77)

That anyone will be appointed is unlikely.

Laka (1990) accounts for this observation by proposing that certain predicates select for inherently negative complementizers, which in turn license NPIs inside their complement, even if it is moved.

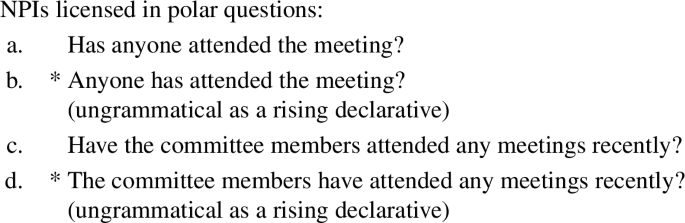

To the extent that a negatively valued C is the common thread among these disparate environments in which NPIs are licensed, it seems that attributing the licensing of subject NPIs to head movement in (73) is too narrow an approach. This is broadly consistent with the vast literature on the licensing of NPIs in English and crosslinguistically, going back to Ladusaw 1979, 1980, McCloskey 1996, Linebarger 1980, Han and Siegel 1997 among others, which makes quite clear that the scope of negation is only one context where licensing may occur. Ladusaw’s (1979) and Fauconnier’s (1975, 1979) major contribution was the observation that NPIs are licensing in downward entailing environments, but a focal point of more recent discussion has been the observation that NPIs are also licensed in interrogative contexts that cannot, on the canonical view, be considered downward entailing (Han and Siegel 1997; Progovac 1993; Nicolae 2013, 2015).

-

(78)

-

(79)

What these examples make clear is that the paradigm in (73) is exceptional, in the sense that NPIs are generally licensed in both polar and wh-interrogatives. The subject-object asymmetry observed in (79) is apparently linked to the observation (Han and Siegel 1997) that the NPI must be c-commanded by the wh-phrase when both are in their base positions; see Nicolae 2013, 2015 for a proposed semantics for questions that relates them back to the idea of a downward entailing context being the key licensing factor, yielding the contrast in (79) as a direct consequence. Whatever the correct unifying analysis, our point here is simply that there is no necessity to appeal to the head movement of negation to a high position as the direct cause of the NPI licensing. It is equally possible that the appearance of negation in a high position and the NPI licensing are both reflexes of a deeper property (e.g., compatibility with some kind of unifying semantic operator).

We conclude that the paradigm under discussion receives a better account without any appeal to head movement. This also has the consequence that this paradigm is no longer a threat to the predictions made by the overall proposal under discussion here.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harizanov, B., Gribanova, V. Whither head movement?. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 37, 461–522 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9420-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9420-5