Abstract

In this paper, I argue that the extended projection of N (xNP) is a phase that does not permit successive-cyclic movement via an edge position (cf. Bach and Horn 1976; Bosque and Gallego 2014). As has been observed previously, languages in which AP and xNP can be extracted from xNP typically involve an overt agreement relation between the extractee and the ‘host.’ I argue that the agreeing morpheme is itself theta-marked by the host N, and that this morpheme also establishes an interpretable Agree relation with the extractee. Given well-motivated assumptions about adjunction and Agree, this enables the extractee to be base-generated outside the host’s extended projection, and hence to be extracted without violating the Phase Impenetrability Condition. As well as accounting for the robust cross-linguistic correlation between overt agreement and extraction, not accounted for under successive-cyclic analyses, the proposed analysis accounts for the peripherality restriction on extraction, the possibility of deep extraction, and exceptions to these. Finally, I examine an apparent exception to the agreement/extraction generalisation, the mobility of PP and inherent-case dependents of N, arguing that this can be captured in terms of an Agree relation between the preposition and the head N.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

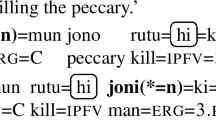

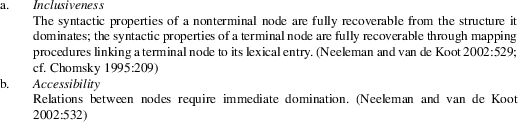

As explained in more detail in Sect. 2, this is based on Neeleman and Van de Koot’s (2002) proposal that syntactic dependencies are established by a ‘selectional function’ (here, simply a ‘selector’) introduced by the dependent element and satisfied through immediate domination of the antecedent. Here, the agreeing affix is the dependent in the Agree relation, and introduces an ‘Agree selector’ (marked [Agr:] on the agreeing affix) that percolates to a node dominating the agreement controler, where it is satisfied (as indicated here by [Agr:#]).

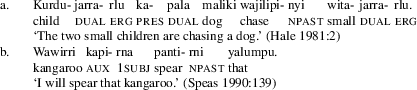

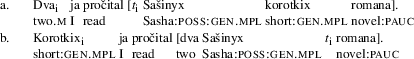

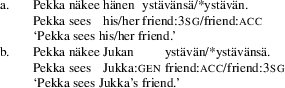

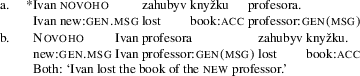

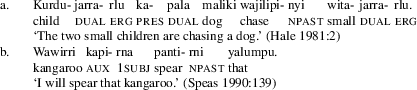

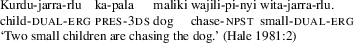

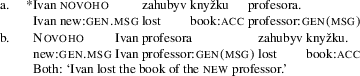

I will not have anything to say about other types of LBE, such as was für and combien splits (e.g., Grosu 1974; Corver 1990), beyond speculating that the presence of a preposition (für, de) may be crucial to permitting extraction in these cases (cf. Sect. 4). I will also not address the topic of ‘inverse splits’ in German, Slavic and other discourse-configurational languages, which may be amenable to an ellipsis analysis (e.g., Fanselow and Ćavar 2002). For example, Warlpiri seems to exhibit an agreement restriction in ‘standard’ splits such as (ia) (Hale 1981), but not in inverse splits such as (ib), in which a sentence-final demonstrative is construed with a sentence-initial object:

-

(i)

-

(i)

Bošković accounts for the impossibility of PP adjunct extraction (cf. Culicover and Rochemont 1992) in a similar manner.

This argument would lose its force if there were some independent reason why the possessor must be generated in the same DP as pro. Yet, under Den Dikken’s analysis, there is no direct connection between the generation of pro within DP (licensed by possessor agreement) and the generation of the dative within DP, so there does not seem to be an intrinsic requirement for the two to be licensed by the same DP. Furthermore, given the dialectal variation in anti-agreement discussed by Den Dikken, at least some cases of possessor-extraction must be derived by movement of the possessor out of DP, even under his analysis. Specifically, pro is only permitted if licensed by overt agreement; thus, the fact that some speakers allow dislocated possessors in the context of anti-agreement means that they allow movement. It is important to note that I am making a weaker claim than Den Dikken about the relevance of agreement, namely that the Agree relation on which possessor-extraction depends is licensed if the language shows at least some evidence of overt agreement between the two positions. That is, the presence of Agree in a particular case does not necessarily require overt agreement in that case (cf. note 7). Thus, provided that Den Dikken’s ‘liberal’ speakers have possessor agreement in at least some cases, the fact that they allow extraction in the context of anti-agreement is consistent with the present proposal.

Authors that have noted the potential relevance of overt inflection include Ross (1967), Horn (1983), Tappe (1989), Zlatić (1997), Gavruseva (2000), Rappaport (2000), Duguine (2008) and Bošković (2013a). Rackowski and Richards (2005) also argue for a connection between Agree (reflected in overt agreement) and extraction, but in a somewhat different sense from the present proposal: Agree must hold between the phase to be extracted from (CP) and the next phase head up (v), rather than between the phase to be extracted from and the extractee. I hope to pursue the connection between the two types of agreement/extraction phenomena in future work.

As has been detailed in a number of publications (e.g., den Dikken 1999; Bartos 2000; É. Kiss 2014), the possessive affix in Hungarian does not always show full agreement with the possessor. Specifically, for the majority of speakers, the possessive affix does not show number agreement with (unextracted) non-pronominal possessors (‘anti-agreement’), either nominative or dative. Bartos (2000) argues, based on coordination data, that there is no zero third person singular agreement morpheme in this case. If this is correct, then it is not possible to argue that possessor extraction always relies on the presence of overt agreement. The claim I make here is somewhat weaker: the presence of overt agreement on some member(s) of the paradigm to which the possessive affix belongs is sufficient for the language learner to posit an Agree relation relating the affix to the possessor for the paradigm as a whole. Note, furthermore, that the implementation of Agree here in terms of selection for a D element by a D element makes it possible to separate the establishment of the relation from the realisation of that relation in terms of agreement. Thus, it may be that, given the cross-linguistic rarity of overt agreement with dative DPs in general, it is possible to establish a selectional relation between a possessive affix and a dative non-pronominal possessor in Hungarian, but not possible for the selector to access the phi-features (or, at least, the number feature) of the dative DP, hence the lack of actual agreement.

On the other hand, there are some cases even within Hungarian that appear to involve extraction being licensed specifically by overt agreement. As den Dikken (1999) observes, speakers of what he calls the ‘majority’ dialect do allow full agreement with non-pronominal dative possessors that have been extracted, while some stricter speakers even require full agreement in this case. One possibility is that agreement here arises from clitic-doubling, rather than from Agree, as clitic-doubling with dative DPs is quite common (being found, e.g., in Basque, Greek and Spanish). Preminger (2009) argues that when an Agree relation cannot be established (‘fails’), either ungrammaticality or default third person singular agreement results, whereas when a clitic-doubling relation cannot be established, this does not give rise to ungrammaticality, but simply entails the absence of a clitic. If ‘full agreement’ with dative DPs is an instance of clitic-doubling, we can account for the fact that the possessor-possessum relation is island-sensitive with either full agreement or anti-agreement, given that both Agree and clitic-doubling are subject to locality restrictions.

I do not have an account of the fact, noted in Grosu (1974), that relative pronouns, which agree with the ‘head’ of the relative, may not be extracted out of NP, but I would speculate that this has to do with information-structural restrictions on ‘split scrambling’ (e.g., Sekerina 1997; Fanselow and Ćavar 2002; Pereltsvaig 2008b).

Boeckx (2003) goes as far as to argue that it is lack of agreement that correlates with extractability, specifically citing the case of Hungarian possessors. He assumes that nominative possessors represent the agreeing case, while dative possessors represent the non-agreeing case, despite the fact that both nominative and dative (both moved and non-moved) possessors may trigger agreement, and in the face of the massive empirical evidence linking agreement to extractability. It is therefore difficult to see how his analysis can be maintained.

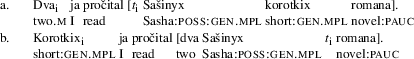

In the appendix to Bošković (2005), he proposes a potential alternative to the idea that the possibility of LBE is related to the absence of DP. He suggests that a link might be established between LBE and the possibility of scrambling, with scrambling languages allowing LBE and non-scrambling languages disallowing it. He further suggests that, if Bošković and Takahashi’s (1998) base-generation approach to scrambling is adopted, the relevance of agreement might be captured if the scrambled XP must enter an Agree relation with its ‘host,’ and that this Agree relation could be the trigger for the LF-lowering of the scrambled XP that Bošković and Takahashi posit. As evidence, Bošković cites the fact that scrambled APs in Warlpiri must agree overtly with their NPs, whereas agreement is optional if the AP is not scrambled. The main problem with this proposal, it seems to me, is that Bošković’s definition of scrambling as “extreme freedom of word order” (2005:37, fn. 54) is too vague to make clear predictions. A language such as (Colloquial) Finnish is a discourse-configurational language, like Hungarian and Russian, yet lacks LBE. It would thus seem to constitute the example of a DP language with scrambling but without LBE that Bošković claims would be an appropriate counterexample to this alternative analysis, but in the absence of a more precise definition of scrambling, this is not clear. In addition, the analysis has nothing to say about the difference between (extractable) dative possessors and (non-extractable) APs in Hungarian.

Bošković (2013a, 2013b) also acknowledges the importance of overt agreement, and proposes an analysis to capture it, but his remit is restricted to a small class of non-agreeing APs in Serbo-Croatian that cannot be extracted from NP. He proposes a solution based on the idea that non-agreeing A must incorporate into N. While this may work for the data in his paper, it does not extend to most of the cases discussed here.

A reviewer suggests that a link between agreement and anti-locality could be established by positing an agreement projection that intervenes between D and NP in languages with overt possessor agreement. Under the assumption that extraction via SpecDP is possible provided anti-locality is respected, an argument of N should be extractable in a DP language with agreement. I agree that this does offer a potential analysis of possessor extraction in DP languages. What would not be not clear under this account is why only agreement of the head N with the possessor should obviate anti-locality, while agreement between AP and the head noun does not. Furthermore, it is not clear how such an analysis would handle the dependence of extraction on agreement in NP languages, as anti-locality is presumably irrelevant in this case.

It is true, as a reviewer points out, that this criticism only applies to the analyses of Duguine, Gavruseva and Rappoport to the extent that they rely on LF-deletion of uninterpretable features. On the other hand, it is difficult to see how the connection between agreement and extraction could be maintained in a principled way under these analyses if the assumption of LF-deletion were dropped. What the present analysis claims is that Agree has interpretative import, and that this explains the greater freedom of extraction in possessor-agreement languages. By contrast, if agreement has no import for the LF interface at all, it is not clear why the presence of agreement (under this alternative a purely morphophonological phenomenon) should facilitate movement out of an otherwise impenetrable domain; in particular, why it should facilitate movement to the escape hatch SpecDP.

Duguine does not make it clear why there should be a causal link between structural case and extraction. See also Baker (2015) for arguments that structural case is not always dependent on agreement.

Zlatić’s (1997) HPSG analysis does not share this assumption, but seems to amount to a stipulation that an extracted left-branch constituent must share the CONCORD feature of the host xNP. Furthermore, the analysis would not extend to agreeing-possessum languages without an additional stipulation.

Almost the converse problem holds of proposals such as Hale (1981) and Nash (1986), if generalised beyond the Warlpiri data for which they were designed, such as (i):

-

(i)

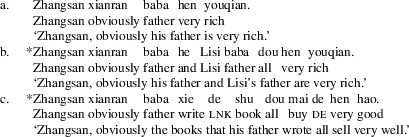

The gist of their proposals is that the two parts of the NP are generated separately and ‘merged’ at the level of ‘logical form’ or ‘semantic interpretation.’ This merger relies on the overt morphology present on both parts of the NP (which is optional on the modifier if the modifier appears adjacent to the noun). This analysis, however, predicts that ‘extraction’ requires identical overt morphology on both parts of the xNP, which is of course not the case for Hungarian-style possessor agreement, nor for languages such as Hindi, in which, in some cases, only the possessor overtly represents the relevant features (e.g., (29a), where the noun kitaab bears no overt morphology representing feminine singular).

-

(i)

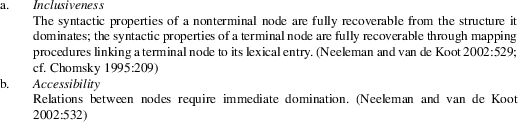

The alternative—and more standard—‘multiple segments’ treatment (e.g., May 1985; Chomsky 1986; Kayne 1994) seems to be motivated only by the assumption that selection takes place only under sisterhood, which is far from obvious (e.g., Collins 2002). Furthermore, the idea that categorial projection is optional in adjunction structures provides a straightforward way of capturing the optionality of stranding adjuncts in VP-fronting contexts; fronting can simply be assumed to apply to the highest node in the V-projection:

-

(i)

-

a.

* I said I would read some long book, and readi I did \(t _{\mathrm{i}}\)LSLT.

-

b.

I said I would read LSLT, and [read LSLT]i I did \(t _{\mathrm{i}}\) quite happily.

-

c.

I said I would read LSLT quite happily, and [read LSLT quite happily]i I did \(t _{\mathrm{i}}\).

-

a.

That said, nothing empirical in this paper appears to hinge on the distinction between the two treatments of adjunction, and the primary advantage of the ‘unlabelled node’ treatment for the purposes of the paper is perspicuity.

-

(i)

The evidence that the prenominal possessor forms a constituent with the possessum is straightforward: the two together may undergo operations that target a single constituent, such as focus-movement in Hungarian (Szabolcsi 1994) or clefting in English.

For concreteness, I assume the following formulation of the PIC, based on Chomsky (2001:13):

-

(i)

Movement of a category X from a position dominated by a phasal node P to a position not dominated by P is impossible. (Category-specific parameter: unless X is a specifier/adjunct of P.)

Under the present proposal, then, the difference between the extended projections of V and N is that the ‘parameter’ in (i) is set to ‘yes’ for V but ‘no’ for N (in Chomsky’s terms, the extended projection of N has no ‘edge’). As a reviewer points out, this difference could not plausibly be derived in terms of a difference in the ability to host ‘edge features’ attracting elements to the phase edge, because I do make use of features (selectors) that attract phrases to the specifier of D (see the discussion of (9b) below). While I admit that the ‘parameter’ in (i) is a stipulation, and I make no attempt to derive it here, it seems to me that the notion of ‘edge feature’ is also a stipulation, as there is no independent evidence supporting the existence of such features. Finally, I assume (following Bošković 2014a) that only the highest projection of an extended projection is phasal. This means that in a DP language, DP is phasal while NP is not, while in an NP language, NP is phasal.

-

(i)

A similar analysis is proposed by Kariaeva (2009), who argues that split NPs in Ukrainian are base-generated as discontinuous and linked via Agree. The main differences between her analysis and the present analysis are that she does not explicitly make the Agree operation dependent on the presence of overt morphology, and she assumes that Agree only operates downwards, which would mean that the analysis could not as it stands be extended to cases where the agreeing element appears on the lower member of the split, as in Hungarian. As a reviewer suggests, however, Kariaeva’s analysis otherwise seems to be consistent with the present analysis.

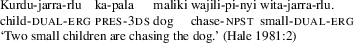

The full definitions are as follows:

-

(i)

-

(i)

Henceforth, for convenience I use referential indices to make clear which element satisfies a given selector, despite the fact that Inclusiveness would ban such indices (see esp. Chomsky 1995:209). I also use abbreviations of pre-theoretical theta-role names (e.g., Ag for Agent, Poss for Possessor), in contrast to Neeleman and Van de Koot’s use of undifferentiated labels for theta-roles in the syntax (e.g., Grimshaw 1990).

The reader is referred to Neeleman and van de Koot (2010) for details of how they derive the requirement for categorial projection and the consequent distinction between internal and external dependencies. Note also that they treat the relation between the verb and its external argument as an external dependency, which means that external argument subjects are base-generated in SpecTP (see esp. Neeleman and van de Koot 2010:341–343).

For simplicity of presentation, I indicate movement here in the standard fashion, rather than in terms of a selector.

The main problem that the reduction of structural case to c-selection appears to face concerns ECM constructions, in which a DP is licensed by a verbal element that does not c-select it. I would suggest the following tentative analysis. Suppose, as seems reasonable, that an ECM verb bears a c-selector (for D) and a theta-selector. Suppose further that the topmost node of its TP complement remains unlabelled (e.g., Chomsky 2013; Rizzi 2015). In that case, the ECM subject and the TP proper (its sister) are equidistant from the V-projection that dominates them. The ECM subject might then plausibly satisfy the verb’s c-selector (which would require satisfaction to be under ‘closest domination,’ rather than ‘immediate domination’ as in Neeleman and Van de Koot), while the TP would satisfy its theta-selector. Where the ECM verb selects a finite clause instead, the two features could both be satisfied by CP, under the assumption that complementisers such as that bear a nominal feature (cf. Rosenbaum 1967; Kayne 1984; see also the related suggestion of Bošković 2007 that C bears phi-features in languages without long-distance agreement into CPs).

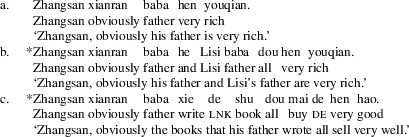

The possessor must surface to the left of the possessum in Mandarin, as in (2b); I assume that this is due to movement forced by the need for the linker de to be adjacent to the head noun (Philip 2012:ch. 3). I assume, following Franco et al. (2015), that linkers in languages such as Mandarin are D elements. Note, though, that Mandarin is still an NP language, as D is not an obligatory component of xNP in this language (see fn. 45). Finally, certain adjectives in Mandarin do not need to bear the linker de, as illustrated in (2b), but this is only possible when a certain semantic relationship holds between the head noun and the adjective, and when the adjective is non-phrasal (Paul 2015:147, 156ff.). One possibility here is that A projects and selects for N (Abney 1987). Again, extraction of A alone would be prevented, either by the PIC or by the Head Movement Constraint.

On this view, (5) is a kind of nominal counterpart of Jelinek’s (1984) ‘pronominal argument’ proposal for languages such as Warlpiri. According to Jelinek, it is the agreement affixes in such languages that function as ‘true’ arguments of a verb, while the lexical NPs whose features they index are syntactically adjuncts. Although the latter aspect of Jelinek’s proposal seems to have become widely accepted in the literature, it has often been argued or assumed that it is not the agreement morphemes themselves that are theta-marked, but instances of pro that are themselves licensed by the agreement morphemes (e.g., Baker 1996; Adger et al. 2009). The main reason for this position seems to be that these languages show the same kinds of subject-object asymmetries (e.g., with respect to binding and weak crossover) as ‘configurational’ languages. Baker’s main argument against expressing these generalisations over morphological structure rather than over syntactic structure in Mohawk is that “there are no clear conceptual advantages to doing so. There would be a decrease in the abstractness of the syntactic representation, but there would be a corresponding increase in the abstractness of the conditions that are defined over syntactic representations. I do not know of anything that would be gained by doing this” (1996:16). As far as I can see, this implies that the choice between the two is empirical, pending further understanding of how we can compare the abstractness of structure and conditions on structure. I believe that the findings in this paper can be taken as empirical evidence that something would be gained by adopting the idea of morphological theta-marking. See also Ackema and Neeleman (2004:85ff.) and Jelinek (2006) for more recent defences of the non-pro-drop analysis of pronominal argument languages.

A reviewer asks why the Agr selector could not be satisfied by the possessum’s D, given the reasonable expectation that a selector should be satisfied by the closest appropriate c-commanding element. I simply assume here that, because Agree in general establishes an external dependency (i.e. one that must be satisfied outside the projection of the category that introduces it), the Agr selector is added to the left of selectors that establish internal dependencies, such as the possessive theta-selector in NP and the R-role in DP. This means that it will be last to be satisfied. Given Neeleman and Van de Koot’s Exclusivity condition (2002:549), which ensures that a given node may only satisfy a single (licensing) function in the immediately dominating node, this will entail that Agr cannot be satisfied by either N (which satisfies Poss) or D (which satisfies R).

That is, I am assuming that there is no such thing as ‘abstract agreement’ in the sense that languages that never realise agreement nevertheless have Agree (cf. Preminger 2017). A reviewer suggests that the presence of possessor extraction in the primary linguistic data might serve as a cue for the language learner to posit Agree, even where there is no overt agreement. I would simply respond that, if syntactic categories and relations are only postulated on the basis of overt evidence in a given language, such examples should not occur in the PLD of a language without agreement in the first place. Furthermore, the case of null operator constructions, mentioned by the reviewer as a case where I would have to posit abstract agreement, should not be problematic given that English does have overtly agreeing operators (who and which, which also participate in number agreement within their clause). That is, the learner would posit that operators in general introduce Agree on the basis that some of them overtly do so. Another reviewer comments that the connection between overt agreement and Agree is just a stipulation, and structures such as (11) “a mere theoretical restatement of the empirical facts.” In a sense, I think the reviewer is correct: the overtness condition is stipulated. This does not, however, seem to me to be a serious problem—it simply goes back to the idea of Borer (1984) that parametric variation should be reduced to morphological variation, the difference here being that variation affects LF-interpretable aspects of structure as well as PF-interpretable aspects. It does not seem to me to be any more questionable theoretically to link overtness with the presence of the relation (i.e., the relation being variable) than to assume that the presence of the relation is universal and its realisation is variable.

This discussion neglects the question of how the dative case on the possessor is licensed. Unfortunately, there is far from a consensus on the nature of dative case in Hungarian. Szabolcsi (1994) argues that it is not a case, but an operator affix, Rákosi (2006) assumes that it is an inherent case and Ürögdi (2006) describes it as a ‘structural case’ but proposes a negative licensing environment for it (it occurs when the DP does not occur locally to T). I will not attempt to enter into this debate, but I will merely note that the range of extractable possessors covers both morphologically case-marked and non-case-marked DPs (Tzotzil and other Mayan languages are good examples of the latter), and that it seems to be agreement which is the unifying factor, which suggests that it has a primary licensing role in these cases. On the other hand, it is undoubtedly the case that inherent case facilitates (apparent) extraction from xNP even in the absence of agreement. I return to this observation in Sect. 4.

Duguine cites Finnish, Mohawk and Palauan as potential counterexamples (cf. Baker 1991:553), but does not discuss the issue further, referring to her own unpublished work. However, it is not clear that any of these are real counterexamples: Mohawk (e.g., Baker 1991:555, 1996:136, fn. 19) and Palauan both show agreement and allow possessor-extraction (Georgopoulos 1991) and Colloquial Finnish both lacks LBE and lacks agreement.

As Boumaa Fijian and Chamorro are article languages (Chung 1991; Dixon 1988:114–116), they can be assumed to be DP languages. Therefore, the impossibility of possessor-extraction in (13a) and its Boumaa Fijian equivalent can be accounted for in the same terms as the failure of linker phrase extraction in DP languages generally, as discussed in 3.2 below.

Huallaga Quechua appears to make use of agreement in both directions in possessor-extraction (Assmann 2014). Possessors trigger number agreement on the possessum, and in addition undergo ‘case-stacking’ when (and only when) extracted. It is not clear to me why both types of agreement should be able to occur in a single language, but it may be that case-stacking is the type of agreement licensing possessor-extraction in this language, while agreement on the possessor has no interpretative import here; cf. fn. 54 on Finnish.

The potentially problematic case here is Bangla, in which nouns do not bear suffixes encoding gender or number. Instead, the singular/plural distinction is encoded in terms of ‘classifiers’ that have been argued to be functional heads in xNP rather than affixes on N (e.g., Bhattacharya 1998). I must leave this as an open question.

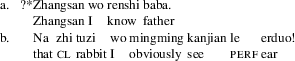

Some of these languages (e.g., Irish) do allow apparent possessor-extraction with the use of a resumptive pronoun in the possessum, but these are normally taken to involve base-generation rather than true extraction (e.g., McCloskey 1990; Duffield 1995). Mandarin Chinese, too, has apparent cases of possessor-extraction, but these are also arguably base-generated (see, e.g., Huang et al. 2009:142). Although Hsu (2009) claims that Mandarin has genuine possessor-extraction, qua movement, the arguments given seem inconclusive. Examples such as (ia), with apparent violation of a subject island, are possible. Yet Hsu uses examples such as (ib–c) as evidence for movement, treating them as violations of the Coordinate Structure Constraint and the Complex NP Constraint respectively (examples from Hsu 2009:96–97):

-

(i)

Such a pattern suggests that this may be a true ‘external possession’ structure that is base-generated (see the discussion in the main text below, and also Vermeulen 2005:71–72, where the same problem is noted for Japanese). As for why possessor ‘extraction’ from objects also shows sensitivity to the CSC and the CNPC, one possibility is that this is because they violate Huang’s (1989) Generalised Control Rule—see especially Li (2014), who argues that subject pro is subject to the GCR (requiring it to take the closest c-commanding nominal as its antecedent), but object pro is not. If possessive pro is more like subject pro, this would account for most of Hsu’s ‘island-violation’ cases. The exception is (iib), to be contrasted with the acceptable (iia) (Hsu 2009:95):

-

(ii)

Hsu attributes the difference to an information-structural restriction, but another possibility is that (iia) represents a pro-possessor structure violating the GCR, while (iib) simply involves an ‘inferential’ relation between a base-generated topic and an NP. Note in this connection that English shows a similar kind of contrast between the following examples:

-

(iii)

-

a.

* As for John, I saw the father.

-

b.

As for the rabbit, I saw the ears!

-

a.

More research is needed, however, to determine whether this analysis can be maintained.

-

(i)

For example, Payne and Barshi (1999:3) use the term ‘external possession’ to describe “[c]onstructions in which a semantic possessor-possessum relation is expressed by coding the possessor as a core grammatical relation of the verb and in a constituent separate from that which contains the possessum,” and Deal (2017) describes external possession as “a phenomenon where a nominal is syntactically encoded as a verbal dependent but semantically understood as the possessor of one of its co-arguments.”

Raising analyses of external possession include Aissen (1979), Munro (1984), Davies (1986), Keach and Rochemont (1994), Landau (1999), Lee-Schoenfeld (2006), Rodrigues (2010) and Deal (2013). Base-generation analyses include Guéron (1985), Hole (2005), Vermeulen (2005), Shklovsky (2012) and É. Kiss (2014).

There is one apparent problem for this analysis: that dative possessors in Hebrew can apparently be related to a DP inside an (argument) PP (Landau 1999). As Pylkkänen notes, though, it is not obvious that these really involve external possession.

What is not immediately obvious under the suggested analysis is how to account for cross-linguistic variation in whether external possessors must be interpreted as ‘affected’ (in particular, whether they must be positively or negatively mentally affected by the matrix event; Haspelmath 1999). Deal notes, following Haspelmath, that the majority of external possession languages studied require external possessors to be ‘affected,’ but that there exist some languages that do not, including Nez Perce, Tzotzil (Aissen 1979), Sierra Popoluca (Marlett 1986), Choctaw (Munro 1984; Davies 1986:ch. 3) and Chickasaw (Munro 1984). (Deal also mentions Malagasy as a potential case, citing Keenan and Ralalaoherivony 2001, but these authors claim that the external possessor must be affected in Malagasy.) Interestingly, in all of these languages, the external possessor triggers agreement on the matrix predicate. It is not clear to me at the moment how to account for this correlation, if it proves to be empirically robust. (Note, though, that the reverse implication does not seem to hold: Swahili is a language in which external possessors trigger matrix agreement, but are subject to an affectedness requirement; Deal 2017.)

The German examples in (23b) and (24b) are due to an anonymous reviewer of this paper.

I assume that, in the absence of a ‘full’ possessor, it is pro that merges with N.

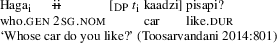

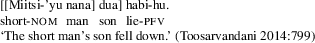

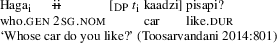

Another potentially more difficult case comes from the Uto-Aztecan language Northern Paiute. Toosarvandani (2014) observes that genitive possessors can be extracted in this language, giving the example in (i):

-

(i)

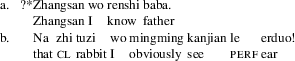

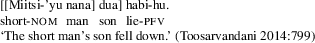

Notably, there is no overt agreement between the possessor and possessum in this case. One possibility that could be considered is that (i) involves a possessor of the Russian type, but with covert agreement. (This is consistent with the fact that Northern Paiute appears to lack true articles, which would make it an NP-language, potentially allowing extraction of agreeing possessors.) As Toosarvandani also notes, there is a kind of agreement between A and N in Northern Paiute, such that A bears the case suffix that might be expected to appear on N (here, nominative, as the possessive functions as a subject):

-

(ii)

One possibility, then, is that possessors are also subject to this kind of ‘case agreement,’ but that Northern Paiute only allows one of the two case suffixes to be overtly expressed. Of course, more research is needed to check whether this is a viable analysis.

-

(i)

I am following Szabolcsi (1983/1984; 1994) in taking the possessor in (26a) to be nominative, as it generally appears in the same form as subjects of clauses. There are alternative views in the literature—for example, Chisarik and Payne (2003) argue that these possessors bear a ‘new genitive’ case, and Dékány (2011) argues that they are caseless—but the question of which is correct does not affect the argumentation here.

I have not been able to check the prediction about possessor-extraction for Macedonian. Note that the proposal specifically refers to extraction of xNP and xAP (leaving aside xPP for the time being). For example, extraction of PP possessors is possible in Bulgarian (e.g., Dimitrova-Vulchanova and Giusti 1998). For more discussion of PP-extraction from xNP, see Sect. 4.

Note that Pashto and Hindi are classified as NP languages even though linkers are Ds (cf. the discussion of demonstratives in Russian in Sect. 3.3). A ‘DP language,’ then, is one in which every extended projection of N contains D. (See also fn. 25.)

This, of course, raises the question of how agreement arises on the linker if it is never attached to the possessum. The most plausible reason is that a linker phrase such as të Benit can involve an elliptical possessor, as such phrases can stand alone without an overt possessor (Dalina Kallulli, p.c.).

Note that interrogative possessors in Romanian surface to the left of the possessum. I assume that the structure of such possessives is similar to that of English Saxon genitives, with movement of the possessor to SpecDP of the possessum—see (9) above.

The examples in (34) and (35), and in fn. 49, are due to Elena Titov (p.c.).

As predicted, the numeral or the AP can be extracted too:

-

(i)

-

(i)

I choose Serbo-Croatian here as an exemplar of Slavic NP languages, as, although its extraction profile is otherwise very similar to that of Russian, Russian does not seem to allow recursive possessives of the type in (38b), preferring to use post-nominal genitives instead (Elena Titov, p.c.).

I assume, in response to a reviewer’s query, that the Adjunct Condition does not block extraction of DP3/NP3, as this phrase is not contained in the projection of the adjunct itself, but it is difficult to give empirical support for this assumption as compared with the alternative that adjunction itself produces a structure that cannot be extracted from.

Other languages in which structural genitives cannot be extracted from xNP include Basque (Artiagoitia 2012) and German (e.g., Gavruseva 2000; Klaus Abels, p.c.). In addition, Corver (1990) and Kariaeva (2009:243) show that Czech and Ukrainian respectively disallow both extraction of adnominal genitives and extraction out of them.

Literary Finnish, which lacks articles and hence can be classified as an NP language, allows AP-extraction from NP (Franks 2007). Because possessives contrast with APs in not exhibiting a true agreement paradigm, the present proposal would predict that possessor extraction should be impossible even in Literary Finnish. I have not been able to test this prediction.

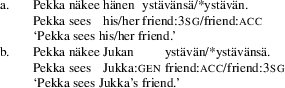

Although Finnish does have a set of possessive affixes for all person and number combinations, they are obligatory only with pronominal (including pro) possessors, as shown in (ia). Full DP possessors, on the other hand, must occur without a possessive marker, as shown in (ib) (examples from Toivonen 2000:581–583):

-

(i)

It is this that differentiates Finnish from Hungarian, which requires a possessive marker (although not necessarily a fully agreeing one) with both pronominal and full DP possessors. This contrast might suggest that the possessive marker in Hungarian is crucially implicated in mediating the possession relation, while that in Finnish is not. Furthermore, the fact that pronominal possessors also cannot be extracted in Finnish, despite obligatory agreement, suggests that it is not strictly speaking the presence of an agreeing element that licenses extraction, but the presence of an agreeing element that is crucially implicated in mediating the possession relation (i.e., obligatory in all cases).

-

(i)

Kariaeva (2009) observes that genitive complements of N can be extracted in Ukrainian as well. Assuming that these also have inherent-case status, this is accounted for. However, another observation of Kariaeva’s presents a puzzle for the analysis of inherent-case complements as PPs proposed below. Although LBE from an in situ inherent-case complement of N is not possible, LBE from an extracted inherent-case complement of N is possible (see also Fanselow and Ćavar 2002):

-

(i)

-

(i)

Grimshaw (1990) divides PP dependents of N into true adjuncts, a(rgument)-adjuncts and true arguments (see also, e.g., Zubizarreta 1985; Szabolcsi 1992; Samek-Lodovici 2003). While true adjuncts such as the by-phrase in (ia) merely modify the R-role of the head N, a-adjuncts such as the by-phrase in (ib) modify a thematic role belonging to N’s LCS. The treatment of both of these as syntactic adjuncts is supported by the fact that they are optional (Grimshaw 1990:109). By contrast, complex event nominals take true arguments (complements), such as the of-phrase in (ib), as reflected by the fact that these are obligatory (the adjective constant here forces the complex event interpretation):

-

(i)

-

a.

a book (by Chomsky)

-

b.

the constant assignment *(of unsolvable problems) (by the teacher)

-

a.

If this basic division in syntactic adjuncts and complements is correct, the analysis in the main text predicts that true arguments of complex event nominals should not be extractable, as this should violate the PIC. Unfortunately, because complex event nominals must occur with a definite determiner (or a definite possessor), it is difficult to control for the possibility that (ii) is relatively bad because of a ‘definiteness island’ effect:

-

(ii)

?*Of what kind of problems did you witness the constant assignment by the teacher?

-

(i)

In a previous draft, I suggested that PPs might universally lack an escape hatch. As two reviewers point out, this raises the question of how to account for P-stranding. One reviewer notes that, if PPs generally lack an escape hatch, P-stranding must involve adjunction of xNP to PP under the present analysis. The reviewer notes that this analysis might account for why P-stranding is easier with prepositions that are more functional in nature, as these are less likely to assign a theta-role and thus to require an Agree relation between P and the xNP. The reviewer further notes that this might also help to account for the fact that P-stranding in English goes hand-in-hand with loss of case morphology, if (as seems plausible) case cannot be assigned across an adjunction structure. Furthermore, pied-piping tends to prefer preservation of case in examples such as With who(m) did you go out?. From a cross-linguistic perspective, too, this analysis is consonant with the fact that the P-stranding Germanic languages have much less case morphology than the non-P-stranding ones. On the other hand, given that xNPs are standardly assumed to bear abstract Case features whether or not they are realised morphologically, together with the fact that the Germanic P-stranding languages do not lack morphological case altogether, I leave this as an unresolved issue, assuming in the main text that languages are parameterised with respect to whether PP is an escape hatch.

See also Kariaeva (2009:243), which provides similar ungrammatical examples from Ukrainian.

References

Abels, Klaus. 2012. Phases: An essay on cyclicity in syntax. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Abney, Steven. 1987. The English noun phrase in its sentential aspect. PhD diss., MIT.

Ackema, Peter, and Ad Neeleman. 2004. Beyond morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ackema, Peter, and Ad Neeleman. 2017. Features of person. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Adger, David, Daniel Harbour, and Laurel Watkins. 2009. Mirrors and microparameters: Phrase structure beyond free word order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Aissen, Judith. 1979. Possessor ascension in Tzotzil. In Papers in Mayan linguistics, ed. Laura Martin. Columbia: Lucas Brothers.

Aissen, Judith. 1996. Pied-piping, abstract agreement, and functional projections in Tzotzil. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 14: 447–491.

Aissen, Judith. 1999. External possessor and logical subject in Tz’utujil. In External possession, eds. Doris L. Payne and Immanuel Barshi, 167–193. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Liliane Haegeman, and Melita Stavrou. 2007. Noun phrase in the generative perspective. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003. The syntax of ditransitives: Evidence from clitics. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Aoun, Joseph, and Yen-hui Audrey Li. 2003. Essays on the representational and derivational nature of grammar: The diversity of wh-constructions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Artiagoitia, Xabier. 2012. The DP hypothesis in the grammar of Basque. In Noun phrases and nominalization in Basque: Syntax and semantics, eds. Urtzi Etxeberria, Ricardo Etxepare, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria, 21–77. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Asbury, Anna. 2008. The morphosyntax of case and adpositions. PhD diss., Utrecht University.

Assmann, Anke. 2014. Case stacking in nanosyntax. In Topics at infl, eds. Anke Assmann et al., 153–196. Leipzig: Institut für Linguistik, Universität Leipzig.

Assmann, Anke, Svetlana Edygarova, Doreen Georgi, Timo Klein, and Philipp Weisser. 2014. Case stacking below the surface: On the possessor case alternation in Udmurt. The Linguistic Review 31: 447–485.

Bach, Emmon, and George M. Horn. 1976. Remarks on ‘Conditions on transformations’. Linguistic Inquiry 7: 265–361.

Baker, Mark. 1991. On some subject/object non-asymmetries in Mohawk. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 9: 537–576.

Baker, Mark. 1996. The polysynthesis parameter. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baker, Mark. 2008. The syntax of agreement and concord. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark. 2015. Case: Its principles and its parameters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bartos, Huba. 2000. Az inflexiós jelenségek szintaktikai háttere. In Strukturalis magyar nyelvtan 3: Morfologia, ed. Ferenc Kiefer, 653–762. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Bhattacharya, Tanmoy. 1998. Specificity in the Bangla DP. In Yearbook of South Asian languages and linguistics, ed. Rajendra Singh. Vol. 2, 71–99. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Bittner, Maria, and Ken Hale. 1996. The structural determination of case and agreement. Linguistic Inquiry 27: 1–68.

Boeckx, Cedric. 2003. Islands and chains: Resumption as stranding. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Borer, Hagit. 1984. Parametric syntax: Case studies in Semitic and Romance languages. Dordrecht: Foris.

Borer, Hagit. 1988. On the morphological parallelism between compounds and constructs. In Yearbook of morphology, eds. Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle, 45–65. Dordrecht: Foris.

Borsley, Robert D., and Ewa Jaworska. 1988. A note on prepositions and case marking in Polish. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 685–691.

Borsley, Robert D., Maggie Tallerman, and David Willis. 2007. The syntax of Welsh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bošković, Željko. 2005. On the locality of left branch extraction and the structure of NP. Studia Linguistica 59: 1–45.

Bošković, Željko. 2007. On the locality and motivation of move and agree: An even more minimal theory. Linguistic Inquiry 38: 589–644.

Bošković, Željko. 2008. What will you have, DP or NP? In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 37, eds. Emily Elfner and Martin Walkow, 101–114. Amherst: GLSA.

Bošković, Željko. 2009. More on the no-DP analysis of article-less languages. Studia Linguistica 63: 187–203.

Bošković, Željko. 2012. On NPs and clauses. In Discourse and grammar: From sentence types to lexical categories, eds. Günther Grewendorf and Thomas Ede Zimmermann, 179–242. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Bošković, Željko. 2013a. Adjectival escapades. In Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL) 21, eds. Steven Franks et al., 1–25. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Bošković, Željko. 2013b. Traces do not head islands: What can PF deletion rescue? In Deep insights, broad perspectives: Essays in honor of Mamoru Saito, eds. Yoichi Miyamoto, Daiko Takahashi, Hideki Maki, Masao Ochi, Koji Sugisaki, and Asako Uchibori, 56–93. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

Bošković, Željko. 2014a. Now I’m a phase, now I’m not a phase: On the variability of phases with extraction and ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 45: 27–89.

Bošković, Željko. 2014b. Phases beyond clauses. In The nominal structure in Slavic and beyond, eds. Lilia Schürcks, Anastasia Giannakidou, and Urtzi Etxeberria, 75–127. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Bošković, Željko, and Serkan Şener. 2014. The Turkish NP. In Crosslinguistic studies on nominal reference: With and without articles, eds. Patricia Cabredo Hofherr and Anne Zribi-Hertz, 102–140. Leiden: Brill.

Bošković, Željko, and Daiko Takahashi. 1998. Scrambling and last resort. Linguistic Inquiry 29: 347–366.

Bosque, Ignacio, and Ángel J. Gallego. 2014. Reconsidering subextraction: Evidence from Spanish. Borealis 3(2): 223–258.

Bowers, John. 1987. Extended X-bar theory, the ECP, and the Left Branch Condition. West Coast Conference on Linguistics (WCCFL) 6: 47–62.

Brattico, Pauli, and Alina Leinonen. 2009. Case distribution and nominalization: Evidence from Finnish. Syntax 12: 1–31.

Brody, Michael. 1993. Θ-theory and arguments. Linguistic Inquiry 24: 1–23.

Brody, Michael. 1997. Perfect chains. In Elements of grammar: Handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 139–167. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Browning, Marguerite. 1987. Null operator constructions. PhD diss., MIT Press.

Campos, Héctor. 2009. Some notes on adjectival articles in Albanian. Lingua 119: 1009–1034.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Reference to kinds across languages. Natural Language Semantics 6: 339–405.

Chisarik, Erika, and John Payne. 2003. Modelling possessor constructions in LFG: English and Hungarian. In Studies in constraint-based lexicalism, eds. Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King, 181–199. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Chomsky, Noam. 1970. Remarks on nominalization. In Readings in transformational grammar, eds. Roderick Jacobs and Peter Rosenbaum, 184–221. Waltham: Ginn.

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Barriers. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–155. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero, and Maria-Luisa Zubizarreta, 133–166. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2013. Problems of projection. Lingua 130: 33–49.

Chung, Sandra. 1991. Functional heads and proper government in Chamorro. Lingua 85: 85–134.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1980. On extraction from NP in Italian. Journal of Italian Linguistics 5: 47–99.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2014. Extraction from DP in Italian revisited. In Locality, eds. Enoch Oladé Aboh, Maria Teresa Guasti, and Ian Roberts, 86–103. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cole, Peter. 1985. Imbabura Quechua. London: Croom Helm.

Collins, Chris. 2002. Eliminating labels. In Derivation and explanation in the minimalist program, eds. Samuel David Epstein and T. Daniel Seely, 42–64. Oxford: Blackwell.

Corbett, Greville G. 1993. The head of Russian numeral expressions. In Heads in grammatical theory, eds. Greville G. Corbett, Norman M. Fraser, and Scott McGlashan, 11–35. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Corver, Norbert. 1990. The syntax of left branch extractions. PhD diss., Tilburg University.

Culicover, Peter W., and Michael S. Rochemont. 1992. Adjunct extraction from NP and the ECP. Linguistic Inquiry 23: 496–501.

Davies, William D. 1986. Choctaw verb agreement and Universal Grammar. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Deal, Amy Rose. 2013. Possessor raising. Linguistic Inquiry 44: 391–432.

Deal, Amy Rose. 2017. External possession and possessor raising. In The Wiley Blackwell companion to syntax, 2nd edn., eds. Martin Everaert, and Henk van Riemsdijk. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118358733.wbsyncom047.

Dékány, Éva. 2011. A profile of the Hungarian DP: The interaction of lexicalization, agreement and linearization with the functional sequence. PhD diss., University of Tromsø.

Despić, Miloje. 2013. Binding and the structure of NP in Serbo-Croatian. Linguistic Inquiry 44: 239–270.

den Dikken, Marcel. 1999. On the structural representation of possession and agreement: The case of (anti)-agreement in Hungarian possessed nominal phrases. In Crossing boundaries: Advances in the theory of Central and Eastern European languages, ed. István Kenesei, 137–178. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Dimitrova-Vulchanova, Mila, and Giuliana Giusti. 1998. Fragments of Balkan nominal structure. In Studies on the determiner phrase, eds. Artemis Alexiadou and Chris Wilder, 333–360. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1988. A grammar of Boumaa Fijian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Duffield, Nigel. 1995. Particles and projections in Irish syntax. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Duguine, Maia. 2008. Structural case and the typology of possessive constructions. In Annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (BLS) 34, eds. Sarah Berson et al., 97–108. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2014. Ways of licensing Hungarian external possessors. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 61: 45–68.

Emonds, Joseph P. 1987. The invisible category principle. Linguistic Inquiry 18: 613–632.

Fanselow, Gisbert, and Damir Ćavar. 2002. Distributed deletion. In Theoretical approaches to universals, ed. Arrtemis Alexiadou, 65–107. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Fanselow, Gisbert, and Caroline Féry. 2013. A comparative perspective on intervention effects on left branch extractions in Slavic. In Non progredi est regredi: Festschrift für Alla Paslawska, eds. Wolodymyr Sulym, Mychajlo Smolij, and Chrystyna Djakiw, 266–295. Lviv: Pais.

Franco, Ludovico, M. Rita Manzini, and Leonardo M. Savoia. 2015. Linkers and agreement. The Linguistic Review 32: 277–332.

Franks, Steven. 1994. Parametric properties of numeral phrases in Slavic. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 12: 597–674.

Franks, Steven. 2007. Deriving discontinuity. In Studies in formal Slavic linguistics, eds. Franc Marušič and Rok Žaucer, 103–120. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Franks, Steven, and Ljiljana Progovac. 1994. On the placement of Serbo-Croatian clitics. Indiana Linguistic Studies 7: 69–78.

Gavruseva, Elena. 2000. On the syntax of possessor-extraction. Lingua 110: 743–772.

Georgopoulos, Carol. 1991. Syntactic variables: Resumptive pronouns and A′ binding in Palauan. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Giorgi, Alessandra, and Giuseppe Longobardi. 1991. The syntax of noun phrases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giurgea, Ion, and Carmen Dobrovie-Sorin. 2013. Nominal and pronominal possessors in Romanian. In The genitive, eds. Anne Carlier and Jean-Christophe Verstraete, 105–139. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1990. Argument structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Grosu, Alexander. 1974. On the nature of the Left Branch Condition. Linguistic Inquiry 5: 308–319.

Guéron, Jacqueline. 1985. Inalienable possession, PRO-inclusion and lexical chains. In Grammatical representation, eds. Jacqueline Guéron, Hans-Georg Obenauer, and Jean-Yves Pollock, 43–86. Dordrecht: Foris.

Haegeman, Liliane. 2004. DP-periphery and clausal periphery: Possessor doubling in West Flemish. In Peripheries, eds. David Adger, Cécile de Cat, and George Tsoulas, 211–240. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hale, Ken. 1981. On the position of Warlbiri in a typology of the base. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Haspelmath, Martin. 1999. External possession in a European areal perspective. In External possession, eds. Doris L. Payne and Immanuel Barshi, 109–135. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Heck, Fabian. 2009. On certain properties of pied-piping. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 75–111.

Hicks, Glyn. 2009. Tough-constructions and their derivation. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 535–566.

Higginbotham, James. 1985. On semantics. Linguistic Inquiry 16: 547–593.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2005. Dimensions of symmetry in syntax: Agreement and clausal architecture. PhD diss., MIT.

Hole, Daniel. 2005. Reconciling ‘possessor’ datives and ‘beneficiary’ datives: Towards a unified voice account of dative binding in German. In Event arguments: Foundations and applications, eds. Claudia Maienborn and Angelika Wöllstein, 213–242. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Holmberg, Anders, and Christer Platzack. 1995. The role of inflection in Scandinavian syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horn, George M. 1983. Lexical-functional grammar. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Hornstein, Norbert. 2001. Move! A minimalist theory of construal. Malden: Blackwell.

Hornstein, Norbert, and Jairo Nunes. 2008. Adjunction, labeling, and bare phrase structure. Biolinguistics 2: 57–86.

Horrocks, Geoffrey, and Melita Stavrou. 1987. Bounding theory and Greek syntax: Evidence for wh-movement in NP. Journal of Linguistics 23: 79–108.

Hoyt, Frederick M. 2010. Negative concord in Levantine Arabic. PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin.

Hsu, Yu-Yin. 2009. Possessor extraction in Mandarin Chinese. In University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 15: 95–104.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. PhD diss., MIT.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1989. Pro-drop in Chinese: A generalized control theory. In The null subject parameter, eds. Osvaldo Jaeggli and Ken Safir, 185–214. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Huang C.-T. James, Yen-hui Audrey Li, and Yafei Li. 2009. The syntax of Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jelinek, Eloise. 1984. Empty categories, case, and configurationality. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 2: 39–76.

Jelinek, Eloise. 2006. The pronominal argument parameter. In Arguments and agreement, eds. Peter Ackema, Patrick Brandt, Maaike Schoorlemmer, and Fred Weerman, 261–288. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kachru, Yamuna. 2006. Hindi. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Kariaeva, Natalia. 2009. Radical discontinuity: Syntax at the interface. PhD diss., Rutgers University.

Kayne, Richard S. 1984. Connectedness and binary branching. Dordrecht: Foris.

Kayne, Richard S. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Keach, Camillia N., and Michael Rochemont. 1994. On the syntax of possessor raising in Swahili. Studies in African Linguistics 23: 81–106.

Keenan, Edward L., and Baholisoa Ralalaoherivony. 2001. Raising from NP in Malagasy. Lingvisticae Investigationes 23: 1–44.

Koster Jan. 1987. Domains and dynasties: The radical autonomy of syntax. Dordrecht: Foris.

Landau, Idan. 1999. Possessor raising and the structure of VP. Lingua 107: 1–37.

Lee-Schoenfeld, Vera. 2006. German possessors: Raised and affected. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 9: 101–142.

Li Yen-Hui Audrey. 2014. Born empty. Lingua 151: 43–68.

Mahajan, Anoop. 1992. The specificity condition and the CED. Linguistic Inquiry 23: 510–516.

Marlett, Stephen A. 1986. Syntactic levels and multiattachment in Sierra Popoluca. International Journal of American Linguistics 52: 359–387.

Mathieu, Eric, and Ioanna Sitaridou. 2002. Split wh-constructions in Classical and Modern Greek. In Linguistics in Potsdam 19, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Susann Fischer, and Melita Stavrou, 143–182.

May, Robert. 1985. Logical form: Its structure and derivation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

McCloskey, James. 1990. Resumptive pronouns, A′-binding and levels of representation in Irish. In Syntax and semantics 23: The syntax of the modern Celtic languages, ed. Randall Hendrick, 199–256. New York: Academic Press.

Mchombo, Sam. 2004. The syntax of Chichewa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morimoto, Yukiko, and Sam Mchombo. 2004. Configuring topic in the left periphery: A case of Chichewa split-NPs. ZAS Papers in Linguistics 35: 347–373.

Munro, Pamela. 1984. The syntactic status of object possessor raising in Western Muskogean. In Annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (BLS), Vol. 10.

Munro, Pamela. 1999. Chickasaw subjecthood. In External possession, eds. Doris L. Payne and Immanuel Barshi, 251–289. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Nash, David G. 1986. Topics in Warlpiri grammar. New York: Garland.

Neeleman, Ad, and Hans van de Koot. 2002. The configurational matrix. Linguistic Inquiry 33: 529–574.

Neeleman, Ad, and Hans van de Koot. 2010. A local encoding of syntactic dependencies and its consequences for the theory of movement. Syntax 13: 331–372.

Nichols, Johanna. 1986. Head-marking and dependent-marking grammar. Language 62: 56–119.

Nikolaeva, Irina. 2002. The Hungarian external possessor in European perspective. In Finno-Ugrians and Indo-Europeans: Linguistic and literary contacts, eds. Cornelius Hasselblatt and Rogier Blokland, 272–285. Maastricht: Shaker.

Nissenbaum, Jon. 2000. Explorations in covert phrase movement. PhD diss., MIT Press.

Nunes, Jairo. 2004. Linearization of chains and sideward movement. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Partee, Barbara H., and Vladimir Borschev. 2003. Genitives, relational nouns, and argument-modifier ambiguity. In Modifying adjuncts, eds. Ewald Lang, Claudia Maienborn, and Cathrine Fabricius Hansen, 67–112. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Paul, Waltraud. 2015. New perspectives on Chinese syntax. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Payne, Doris L., and Immanuel Barshi. 1999. External possession: What, where, how, and why. In External possession, eds. Doris L. Payne and Immanuel Barshi, 3–29. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Pereltsvaig, Asya. 2007. The universality of DP: A view from Russian. Studia Linguistica 61: 59–94.

Pereltsvaig, Asya. 2008a. Copular sentences in Russian. Berlin: Springer.

Pereltsvaig, Asya. 2008b. Split phrases in Colloquial Russian. Studia Linguistica 62: 5–38.

Pesetsky, David. 2013. Russian case morphology and the syntactic categories. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Pesetsky, David, and Esther Torrego. 2001. T-to-C movement: Causes and consequences. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 355–426. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Pesetsky, David, and Esther Torrego. 2007. The syntax of valuation and the interpretability of features. In Phrasal and clausal architecture, eds. Simin Karimi, Vida Samiian, and Wendy K. Wilkins, 262–294. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Philip Joy Naomi. 2012. Subordinating and coordinating linkers. PhD diss., UCL.

Preminger, Omer. 2009. Breaking agreements: Distinguishing agreement and clitic-doubling by their failures. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 619–666.

Preminger, Omer. 2017. What the PCC tells us about ‘abstract’ agreement, head movement, and locality. Ms., University of Maryland.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2008. Introducing arguments. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rackowski, Andrea, and Norvin Richards. 2005. Phase edge and extraction: A Tagalog case study. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 565–599.

Radford, Andrew. 2000. NP-shells. Essex Research Reports in Linguistics 33: 2–20.

Rákosi, György. 2006. Dative experiencer predicates in Hungarian. PhD diss., Utrecht University.

Rappaport, Gilbert C. 2000. Extraction from nominal phrases in Polish and the theory of determiners. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 8: 159–198.

Rappaport, Gilbert C. 2002. Numeral phrases in Russian: A minimalist approach. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 10: 329–342.

Reeve, Matthew. 2011. The syntactic structure of English clefts. Lingua 131: 142–171.

Reeve, Matthew. 2012. Clefts and their relatives. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

van Riemsdijk, Henk. 1978. A case study in syntactic markedness: The binding nature of prepositional phrases. Lisse: Peter de Ridder.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2015. Notes on labeling and subject positions. In Structures, strategies and beyond: Studies in honour of Adriana Belletti, eds. Elisa Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamann, and Simona Matteini, 17–46. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Roberts, Taylor. 2000. Clitics and agreement. PhD diss., MIT Press.

Rodrigues, Cilene. 2010. Possessor raising through thematic positions. In Movement theory of control, eds. Norbert Hornstein and Maria Polinsky, 119–142. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Rosenbaum, Peter S. 1967. The grammar of English predicate complement constructions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ross, John R. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. PhD diss., MIT.

Saito, Mamoru, and Keiko Murasugi. 1999. Subject predication within IP and DP. In Beyond principles and parameters: Essays in memory of Osvaldo Jaeggli, eds. Kyle Johnson and Ian Roberts, 167–188. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Samek-Lodovici, Vieri. 2003. The internal structure of arguments and its role in complex predicate formation. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21: 835–881.

Samvelian, Pollet. 2006. When morphology does better than syntax: The ezafe construction in Persian. Ms., Université de Paris 3.

Sánchez, Liliana. 1996. Why does Southern Quechua agree in person nominally? Ms., Carnegie Mellon University.

Sekerina, Irina. 1997. The syntax and processing of scrambling constructions in Russian. PhD diss., CUNY.

Shackle, Christopher. 2003. Panjabi. In The Indo-Aryan languages, eds. George Cardona and Dhanesh Jain, 581–621. London: Routledge.

Shklovsky, Kirill. 2012. Tseltal clause structure. PhD diss., MIT.

Speas, Margaret. 1990. Phrase structure in natural language. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Starke, Michal. 2001. Move dissolves into Merge: A theory of locality. PhD diss., University of Geneva.

Stjepanović, Sandra. 2010. Left branch extraction in multiple wh-questions: A surprise for question interpretation. Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL) 18: 502–517.

Stjepanović, Sandra. 2012. Differential object marking in Serbo-Croatian: Evidence from left branch extraction in negative concord constructions. Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL) 19: 99–115.

Svenonius, Peter. 2004. On the edge. In Peripheries: Syntactic edges and their effects, eds. David Adger, Cécile de Cat, and George Tsoulas, 259–287. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1983/1984. The possessor that ran away from home. The Linguistic Review 3: 89–102.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1992. Subject suppression or lexical PRO? The case of derived nominals in Hungarian. Lingua 86: 149–176.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1994. The noun phrase. In Syntax and semantics, vol. 27: The syntactic structure of Hungarian, eds. Ferenc Kiefer and Katalin É. Kiss, 179–274. New York: Academic Press.

Talić, Aida. 2013. Extraordinary complement extraction: PP-complements and inherently case-marked nominal complements. Studies in Polish Linguistics 8: 127–150.

Tappe, Hans-Thilo. 1989. A note on split topicalization in German. In Syntactic phrase structure phenomena in noun phrases and sentences, eds. Christa Bhatt, Elisabeth Löbel, and Claudia Schmidt, 159–179. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Ticio, Emma. 2005. Locality and anti-locality in Spanish DPs. Syntax 8: 229–286.

Toivonen, Ida. 2000. The morphosyntax of Finnish possessives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 18: 579–609.

Toosarvandani, Maziar. 2014. Two types of deverbal nominalization in Northern Paiute. Language 90: 786–833.

Uriagereka, Juan. 1988. On government. PhD diss., University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Ürögdi, Barbara. 2006. Predicate fronting and dative case in Hungarian. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 53, 291–332.

Vainikka, Anne. 1989. Deriving syntactic representations in Finnish. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Vainikka, Anne. 1993. Three structural cases in Finnish. In Case and other topics in Finnish syntax, eds. Anders Holmberg, and Urpo Nikanne, 129–159. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Vermeulen, Reiko. 2005. External possession: Its basis in theta-theory. PhD diss., University College London.

Webelhuth, Gert. 1992. Principles and parameters of syntactic saturation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wei, Ting-Chi. 2011. Island repair effects of the Left Branch Condition in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 20: 255–289.

Williams, Edwin. 1981. Argument structure and morphology. The Linguistic Review 1: 81–114.

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2008. On the syntactic flexibility of formal features. In The limits of syntactic variation, ed. Theresa Biberauer, 143–174. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2012. There is only one way to agree. The Linguistic Review 29: 491–539.

Zlatić, Larisa. 1994. An asymmetry in extraction from noun phrases in Serbian. In 9th Biennial Conference on Balkan and South Slavic Linguistics, Literature, and Folklore, 207–216. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistic Club.

Zlatić, Larisa. 1997. The structure of the Serbian Noun Phrase. PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin.

Zubizarreta, Maria Luisa. 1985. The relation between morphophonology and morphosyntax: The case of Romance causatives. Linguistic Inquiry 16: 247–289.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people for judgements and related discussion: Klaus Abels, Priyanka Biswas, Margarita Dimitrovna, Ion Giurgea, Güliz Güneş, Atakan İnce, Dalina Kallulli, Gergely Kantor, Yadgar Karimi, Rajvir Kaur, Anikó Lipták, Anoop Mahajan, Mihaela Marchis Moreno, Radovan Miletić, Otto Nuoranne, Kriszta Szendrői, Elena Titov and Jana Willer-Gold. I am especially grateful to Ludovico Franco and Mihaela Marchis Moreno, who read and commented on a previous draft of the paper, and to the three anonymous reviewers of this paper, for extremely helpful comments. The usual disclaimers apply. This work was largely carried out while I was a postdoctoral researcher on Ludovico Franco’s project ‘The Case of Agreement’ at the Centro de Linguística, Universidade Nova de Lisboa (CLUNL), and I am grateful to the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), who funded the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reeve, M. An agreement-based analysis of extraction from nominals. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 37, 263–314 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9406-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9406-3