Abstract

We argue that the unusual morphological template in the noun phrase of Meadow Mari should be derived on the basis of a simple, semantically transparent syntax. In accordance with the Mirror Principle, the analysis we propose derives the actual surface order of morphemes in Mari by means of two postsyntactic reordering operations: A lowering operation and a metathesis operation. Evidence for this account comes from a process called Suspended Affixation. This process is known to delete the right edges of non-final conjuncts under recoverability. We show however, that Suspended Affixation in Mari does not apply to the right edges of surface orders. Rather, the right edges of an intermediate postsyntactic representation are relevant. Suspended Affixation applies after some but not all postsyntactic operations have applied. Thus, the account we present makes a strong argument for a stepwise derivation of the actual surface forms and thus for a strongly derivational architecture of the postsyntactic module.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While the Mirror Principle was originally conceived of as applying only to syntactic operations such as passivization, it has often been generalized to include all affixes to reflect the order of syntactic heads (see e.g. Brody 2000 et seq.’s notion of what he calls the ‘Mirror Generalization’). Given a modern Chomskyan architecture of syntax with merge as the only syntactic operation available, the original Mirror Principle and the generalized version are to be seen as equivalent.

The abbreviations in the second column are: Num is the number morpheme, D is the location of the possessive affix, K1 is the host of the local case features and K2 is the host of the structural case features.

Throughout this paper, affixes that take scope over both conjuncts are given in bold.

For definition and extensive discussion of clitics, see Zwicky (1985), Miller (1992), Halpern (1995). In all of these works, clitics are defined in such a way that the suppletion data in (14) rule out an analysis of SA as cliticization. Halpern (1995) for example explicitly states that elements he derives in terms of the Edge Feature Principle are predicted to show no signs of lexical interactions with the base they attach to. Only postlexical rules can affect clitics. In this system, however, triggering suppletion is clearly not a postlexical rule. See Erschler (2012), Weisser (2017a,b) for further arguments that support the claim that SA is a deletion operation.

A similar argument for SA being an instance of actual deletion can be made on the basis of Turkish where Kornfilt (2012) has shown that phonological rules such as vowel harmony can bleed the application of SA as they change the form of the affix (see discussion of these facts in Sect. 6.3). It is implausible to assume that the possibility to cliticize to the conjunction phrase depends on the phonological properties of the first (i.e. the non-adjacent) conjunct.

With respect to the example in (25), it seems that there is a certain variation among speakers of Turkish. For some speakers, examples in which the possessive affix is deleted but the plural marker is not are degraded (see e.g. judgments in Orgun (1996) and Kornfilt (1996, 2012). Kabak (2007) claims that at least some of these examples are well-formed. This speaker variation does not affect our argument here. As we will see, there are affix-specific restrictions in Turkish on the availability of SA. Crucially, the Right-Edge condition still holds even if examples such as (25b) are degraded for some speakers.

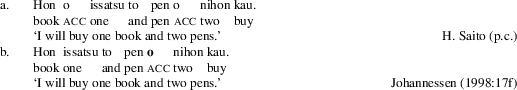

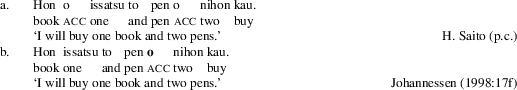

An anonymous reviewer also expresses her/his surprise about the fact that the Right-Edge condition can be violated in Mari (at least on the surface) and asks whether we know of other cases like the one at hand. In fact, we are aware of one other case where an affix can be deleted by SA even though it is not at the right edge. The crucial examples are found in the nominal domain in Japanese and Korean. These languages allow for DP-internal extraposition of the numeral-classifier complex to a position after the case marker. The case marker can however still undergo SA. In (ia), which is also a possible option, no SA applies which allows us to see the position of the case marker. In (ib), SA applies.

-

(i)

Without going too much into detail, it seems that for these data, a similar explanation can be provided as the one we will put forward for Mari. This kind of numeral-classifier extraposition has been identified as an instance of quantifier floating. As this kind of quantifier floating has been argued to be an adjunction operation (see e.g. Bobaljik (1998)) and adjuncts are often argued to be inserted late into the structure, we can entertain a possible analysis in which SA precedes this kind of adjunction. If this analysis is feasible, then the violation of the Right-Edge condition in Japanese (and Korean) is also only apparent.

-

(i)

Modulo vowel harmony. However, unlike in Turkish, vowel harmony does not have an effect on SA (see Sect. 6.2 for the Turkish examples).

Apart from McFadden (2004), there are, of course, many predecessors to the underlying structure we assume. The general architecture of DPs with a D-head taking an NP as its complement goes back to Abney (1987) and was adopted by most accounts in the field. The intermediate number head was introduced by Ritter (1992) and argued for by a number of papers, i.a. Alexiadou and Wilder (1998), Harley and Ritter (2002). Introducing a K-head heading the whole structure was proposed i.a. by Travis (1986), Travis and Lamontagne (1992), Bittner and Hale (1996), Bayer et al. (2001). And, as for the position of K, it is very plausible to assume that K modifies the whole DP rather than just a constituent of it. This insight goes back to a whole number of accounts which stress the similarities of case and adpositions. (see e.g. Kayne 1984; Emonds 1985)

I follow McFadden (2004) who gives an argument for this process applying on the basis of hierarchical structure. The argument itself is based on allomorphy patterns in Mordvin, another Eastern Uralic language. Thus, while this assumption may lack concrete support within Meadow Mari, it combines nicely with the rest of the analysis and the general order of operations discussed below.

As pointed out in Sect. 3, non-application of sa may actually not result in strong ungrammaticality but rather in degradedness of some sort.

In case the reader might consider this reference to a certain feature as overly unrestricted, we want to propose an alternative account that introduces an additional postsyntactic operation called K-fission (k-f). k-f splits up the features on K into two distinct heads K1 and K2, the former containing all local case features and the latter containing structural case features. As a result, one could reformulate D-Metath to the extent that it merely refers to K1. This may have the additional benefit of being able to explain cases as the Udmurt example (3) in Sect. 2, in which actual stacking of a local and a structural case occurs.

A quick note is in order about the cases where metathesis seems to be optional, i.e. dative and comparative case. In order to derive the variable placement of these cases, we stipulate that, with these cases, the local case feature is optionally present on the K-head. As a consequence, metathesis is optional and the variable placement is derived. Depending on whether metathesis applies, the dative and the comparative either behave like a local or like a structural case.

For the sake of completeness, it should be noted that our theory also predicts the reverse pattern to hold. The possessive affixes should be able to undergo SA only when they are at the right edge. Here, the pattern is not that clear. Apparently, while the non-elliptical reading in examples like (i) is strongly favored, the elliptical reading seems to be marginally possible if it is pushed by the context. This is somewhat unexpected given our analysis and we cannot provide an explanation for these cases at this point. However, we want to note that the two readings are not that different and it may be the case that there are pragmatic processes at play that allow speakers to induce a certain reading from context rather than from the underlying semantics.

-

(i)

sad-vlak den pasu-na-vlak

garden-pl and field-1pl-pl

‘Gardens and our fields’

? ‘Our gardens and fields’

-

(i)

As it does not affect our main point here, we leave aside the question whether this free variation can be derived more satisfyingly (e.g. by saying that, for some speakers, even unvalued (i.e. phonologically empty) D is enough to trigger the form -eške.) To substantiate such claims, more data from a variety of different speakers would be necessary.

The suppletive form of the first person plural pronoun in these cases derives from a stem /mem/ plus the affix /na/ which is the possessive marking for first person plural. The fact that pronouns bear possessive marking is a widespread phenomenon in Finno-Ugric (see e.g. Spencer and Stump 2013 on Hungarian). Historically, it is due to the fact that case markers once were nouns which could themselves bear possessive affixes. In Hungarian, for example, this pattern seems to be productive but in Mari, these forms are lexicalized and simply treated as suppletive stems.

Pronouns do normally not inflect for local cases. Instead either postpositional constructions or periphrastic constructions (‘someone like me’) are used.

Another fact that puts emphasis on the derivational model that underlies the analysis is the violation of the Obligatory Precedence Principle, which states that obligatory rules must precede optional rules (Ringen 1972; also cf. Perlmutter and Soames 1979; Georgi 2014). As we have seen, D-Lower is optional and precedes several obligatory operations such as D-Metath. However, as was made clear in the discussion above, the order of these operations must be the way we presented it.

But given that both rules apply on different kinds of structures (D-Lower applies on the basis of hierarchical structures and D-Metath applies on the basis of linear order) it becomes clear that they cannot compete. In Arregi and Nevins’ (2008, 2012) terminology, they apply in different components within the postsyntactic module. D-Lower applies in what the call the Exponence Conversion component whereas D-Metath is part of the Linear Operations component. Thus, while it still may be the case that something like the Obligatory Precedence Principle applies within one component, it cannot be the case that it applies across components overall.

The table in (73) is slightly simplified as it does not illustrate all possible candidates. Candidates with a non-initial root as well as a K-head immediately following the root are not shown for ease of exposition. These candidates do not play a role here as they can easily be excluded by high ranked constraints. Also, we have translated Ryan’s somewhat unusual constraint system into one which makes use of more standard markedness constraints. Although there are cases in Ryan’s paper where this difference is of importance, it does, as far as we can see, not make a substantial difference in the discussion here.

He alludes to Kroch’s (2000) ‘Grammars in competition’-account and states that Western Hill Mari does not have lowering of D to Num. In this account, Meadow Mari speakers have access to both the Hill Mari and the Eastern Mari grammars.

It should be noted though that, for now, we cannot provide an answer as to why certain conjunctions seem to prohibit SA whereas others allow it. We treat this fact as a more or less arbitrary lexical property that certain conjunctions in some languages have or do not have.

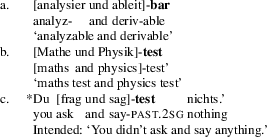

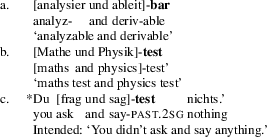

Interestingly, we find the exact reverse situation in German or Dutch where inflectional affixes cannot be deleted whereas derivational affixes and parts of compounds can.

-

(i)

It has been argued, however that this is a purely phonological process that does not make reference to anything else but phonological wordhood (see Booij 1985 and Wiese 1996). We leave the question open for now whether SA in Turkish and Mari is the same underlying process we see in German.

-

(i)

As an anonymous reviewer points out that the ungrammaticality of (83b) is not necessarily tied to the cases of vowel harmony. SA of pronouns seems to be problematic in many cases on independent grounds (see also Erschler 2012).

An anonymous reviewer asks the question what the parameter is that governs the application of SA at a certain point of the (PF-)derivation and whether we expect further variation along these lines. While we acknowledge that this is the right question to ask, at this point, we cannot provide an answer to it. For now, we confine ourselves to showing that the facts can be derived using our system. However, given that SA in languages like Turkish can, for some speakers, be sensitive to phonological operations such as vowel harmony, it strikes us as plausible that there can be cross-linguistic variation as to which module SA applies in. It is of course a very interesting question for future research to see at which points of the derivation SA can apply and how it interacts with morphophonological processes.

References

Abney, Steven. 1987. The English noun phrase in its sentential aspect. PhD diss., MIT.

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Chris Wilder. 1998. Possessors, predicates and movement in the determiner phrase. Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Alhoniemi, Alho. 1993. Grammatik des Tscheremissischen (Mari): Mit Texten und Glossar. Hamburg: Buske.

Anderson, Stephen. 1974. The organization of phonology. New York: Academic Pres.

Arregi, Karlos, and Andre Nevins. 2008. A principled order to postsyntactic operations. Available at lingbuzz/000646. Accessed 30 January 2018.

Arregi, Karlos, and Andrew Nevins. 2012. Morphotactics: Basque auxiliaries and the structure of spellout. Dordrecht: Springer.

Assmann, Anke, Svetlana Edygarova, Doreen Georgi, Timo Klein, and Philipp Weisser. 2014. Case stacking below the surface: On the possessor case alternation in Udmurt. The Linguistic Review 31 (3–4): 447–485.

Baker, Mark. 1985. The Mirror Principle and morphosyntactic explanation. Linguistic Inquiry 16 (3): 373–415.

Baković, Eric. 2011. Opacity and ordering. In The handbook of phonological theory, 2nd edn., eds. John A. Goldsmith, Jason Riggle, and Alan C. L. Yu, 40–67. Hoboken: Wiley.

Bayer, Josef, Markus Bader, and Michael Meng. 2001. Morphological underspecification meets oblique case: Syntactic and processing effects in German. Lingua 111: 465–514.

Bittner, Maria, and Ken Hale. 1996. The structural determination of case and agreement. Linguistic Inquiry 27 (1): 1–68.

Bobaljik, Jonathan. 1998. Floating quantifiers: Handle with care [State of the article]. Glot International 3 (6): 3–10.

Booij, Gert. 1985. Coordination reduction in complex words: A case for prosodic phonology. In Advances in nonlinear phonology, eds. Harry van der Hulst and Norval Smith. Dordrecht: Foris.

Broadwell, George Aaron. 2008. Turkish suspended affixation is lexical sharing. In Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG08) Conference, eds. Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King. Stanford: CSLI.

Brody, Michael. 2000. Mirror theory: Syntactic representation in perfect syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 31 (1): 29–56.

Bybee, Joan. 1985. Morphology: A study of relation between form and meaning. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Chomsky, Noam, and Morris Halle. 1968. The sound pattern of English. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Crysmann, Berthold, and Olivier Bonami. 2016. Variable morphotactics in information-based morphology. Journal of Linguistics 52 (2): 311–374.

Embick, David, and Rolf Noyer. 2001. Movement operations after syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 32: 555–595.

Emonds, John. 1985. A unified theory of syntactic categories. Dordrecht: Foris.

Erschler, David. 2012. Suspended affixation and the structure of syntax-morphology interface. Studia Linguistica Hungarica 59: 153–175.

Georgi, Doreen. 2014. Opaque interactions of merge and agree: On the nature and order of elementary operations. PhD diss., Leipzig University.

Givón, Talmy. 1971. Historical syntax and synchronic morphology: An archeologist’s field trip. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 7, 394–415.

Göksel, Aslı, and Cecilia Kerslake. 2005. Turkish: A comprehensive grammar. London: Routledge.

Good, Jeff, and Alan Yu. 2005. Morphosyntax of two Turkish subject pronominal paradigms. In Clitic and affix combinations: Theoretical perspectives, eds. Lorie Heggie and Francisco Ordonez, 315–341. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Gruzdeva, Ekaterina. 1998. Nivkh. Munich: Lincom Europa.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1997. Distributed morphology: Impoverishment and fission. In MITWPL 30: Papers at the interfaces, eds. Benjamin Bruening, Yoonjung Kang, and Martha McGinnis, 425–449. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Halpern, Aaron. 1995. On the morphology and the placement of clitics. Stanford: CSLI.

Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002. Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language 78: 482–526.

Harris, James, and Morris Halle. 2005. Unexpected plural inflections in Spanish: Reduplication and metathesis. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 196–222.

Heck, Fabian, and Gereon Müller. 2007. Extremely local optimization. In Western Conference on Linguistics (WECOL) 26, eds. Erin Brainbridge and Brian Agbayani, 170–183. Fresno: California State University Fresno.

Johannessen, Janne Bondi. 1998. Coordination. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kabak, Barış. 2007. Turkish Suspended Affixation. Linguistics 45 (2): 311–347.

Kayne, Richard. 1984. Connectedness and binary branching. Dordrecht: Foris.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1973. Abstractness, opacity and global rules. In Three dimensions in linguistic theory, ed. Osamu Fujimura, 57–86. Tokyo: TEC.

Kiparsky, Paul. 2000. Opacity and Cyclicity. The Linguistic Review 17: 351–365.

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 1996. On some copular clitics in Turkish. ZAS Papers in Linguistics 6: 96–114.

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 2012. Revisiting “suspended affixation” and other coordinate mysteries. In Functional heads: The cartography of syntactic structures, eds. Laura Brugé, Anna Cardinaletti, Giuliana Giusti, Nicola Munaro, and Cecilia Poletto, Vol. 7. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kroch, Anthony. 2000. Syntactic change. In The handbook of contemporary syntactic theory, eds. Mark Baltin and Chris Collins. Hoboken: Blackwell.

Luutonen, Jorna. 1997. The variation of morpheme order in Mari declesion. Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seuran Toimituksia [Publications of the Finno-Ugrian Society] 226.

McCarthy, John. 1999. Sympathy and phonological opacity. Phonology 16: 331–399.

McCarthy, John. 2000. Harmonic serialism and parallelism. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 30, eds. Masako Hirotani, Andries Coetzee, Nancy Hall, and Ji-Yung Kim. Amherst: GLSA.

McCarthy, John. 2007. Hidden generalizations: Phonological opacity in Optimality Theory. London: Equinox.

McFadden, Thomas. 2004. The position of morphological case in the derivation: A study on the syntax-morphology interface. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands and the theory of ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, Philip. 1992. Clitics and constituents in phrase structure grammar. PhD diss., University of Utrecht.

Moravcsik, Edith. 2003. Inflectional morphology in the Hungarian noun phrase: A typological assessment. In Noun phrase structure in the languages of Europe, ed. Frans Plank. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Murphy, Andrew. 2016. Subset relations in ellipsis licensing. Glossa: A journal of general linguistics 1 (1): 44.

Myler, Neil. 2013. Linearization and post-syntactic operations in the Quechua DP. In Challenges to linearization, eds. Theresa Biberauer and Ian Roberts, 171–210. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Nishiyama, Kunio. 2012. Japanese verbal morphology in coordination. Handout for the Workshop on Suspended Affixation, Cornell University.

Orgun, Orhan. 1996. Suspended Affixation: A new look at the phonology-morphology Interface. In Interfaces in phonology: Studia grammatica 41, ed. Ursula Kleinhenz, 251–261. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Perlmutter, David, and Scott Soames. 1979. Syntactic argumentation and the structure of English. Berkeley: The University of California Press.

Pullum, Geoffrey. 1976. The Duke of York gambit. Journal of Linguistics 12 (1): 83–102.

Pullum, Geoffrey. 1979. Rule organization and the interaction of a grammar. New York: Garland.

Rice, Keren. 2000. Morpheme order and semantic scope. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ringen, Catherine. 1972. On arguments for rule ordering. Foundations of Language 8: 266–273.

Ritter, Elizabeth. 1992. Cross-linguistic evidence for number phrase. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 37: 197–218.

Ryan, Kevin. 2010. Variable affix order: Grammar and learning. Language 86 (4): 758–791.

Salzmann, Martin. 2013. Rule ordering in verb cluster formation: On the extraposition paradox and the placement of the infinitival particle te/zu. In Rule interaction in grammar, eds. Anke Assmann and Fabian Heck. Vol. 90 of Linguistische Arbeitsberichte.

Spencer, Andrew. 2003. Putting some order into morphology: Reflections on Rice (2000) and Stump (2001). Journal of Linguistics 39 (3): 621–646.

Spencer, Andrew. 2008. Does Hungarian have a case system? In Case and grammatical relations, eds. Greville Corbett and Michael Noonan, 35–56. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Spencer, Andrew, and Gregory Stump. 2013. Hungarian pronominal case and the ordering of content and form in inflectional morphology. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31: 1207–1248.

Stump, Gregory. 2001. Inflectional morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Travis, Lisa. 1986. The case filter and the ecp. McGill Working Papers in Linguistics 3 (2): 51–75.

Travis, Lisa, and Gregory Lamontagne. 1992. The Case Filter and the licensing of empty K. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 37: 157–174.

Trommer, Jochen. 2008. “Case suffixes”, postpositions and the phonological word in Hungarian. Linguistics 46: 403–437.

van Oostendorp, Marc. 2007. Derived environment effects and consistency of exponence. In Freedom of analysis?, eds. Sylvia Blaho, Patrik Bye, and Martin Krämer, 123–148. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Weisser, Philipp. 2016. Three types of Coordination in Udmurt. Ms., Universität Leipzig.

Weisser, Philipp. 2017a. On the symmetry of case in conjunction. Ms., Universität Leipzig.

Weisser, Philipp. 2017b. Why there is no such thing a Closest Conjunct Case. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 47, eds. Andrew Lamont and Katerina Tetzloff, 219–232.

Wiese, Richard. 1996. The phonology of German. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yoon, James Hye Suk. 2012. Lexical integrity and suspended affixation in two types of denominal predicates in Korean. Talk given at Workshop on Suspended Affixation, Cornell University.

Yoon, James Hye Suk, and Wooseung Lee. 2005. Conjunction Reduction and Its Consequences for Noun Phrase Morphosyntax in Korean. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 24, eds. John Alderete, Chung hye Han, and Alexei Kochetov, 379–387.

Zwicky, Arnold. 1985. Clitics and particles. Language 61 (2): 283–305.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for numerous comments on various versions of this paper. We are particularly indebted to Jonathan Bobaljik, Doreen Georgi, Kadir Gökgöz, Laura Kalin, Gereon Müller, Andrew Murphy, Andrew Nevins, Susi Wurmbrand as well as the audiences of the UConn Linglunch; PLC 40 at UPenn and GLOW 39 at Göttingen. We furthermore want to thank three anonymous reviewers who helped improve the paper significantly. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Research Grant Number BCS-1451098, PI: Bobaljik) as well as the Feodor-Lynen Program of the Alexander-von-Humboldt Foundation (Projects: ‘Case and Coordination’ and ‘Consequences of the SOCIC Generalization’).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guseva, E., Weisser, P. Postsyntactic reordering in the Mari nominal domain. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 36, 1089–1127 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9403-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9403-6