Abstract

Malagasy clauses have a bipartite structure, consisting of a predicate plus a topic-like constituent, the trigger, which specifies the argument of predication. Normally the predicate precedes the trigger. The question arises as to whether the trigger originates to the right of the predicate, or whether predicate-trigger order is derived through predicate fronting. I argue in favor of predicate fronting based on evidence from clausal complements in sentences denoting direct perception of an event. These complements closely resemble matrix clauses, but exhibit an order where the trigger precedes the predicate. I show that these complements are single constituents which pattern as tensed clauses with regard to binding and other tests. I also present evidence that the trigger in perception verb complements occupies the same position as triggers of predicate-initial clauses. It follows that the word order difference between perception verb complements and predicate-initial clauses reflects a difference in the surface position of the predicate. I propose that predicate-initial clauses include a finiteness (Fin) head in their left periphery which attracts the predicate (=TP) to check tense and EPP features, causing the predicate to raise over the trigger. In perception verb complements, which denote events rather than propositions, the Fin head is absent, and so predicate fronting fails to occur.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

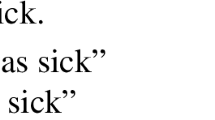

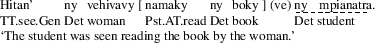

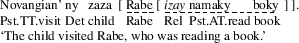

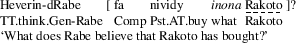

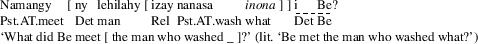

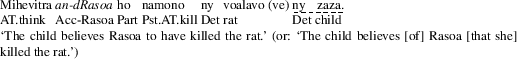

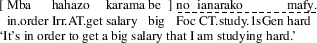

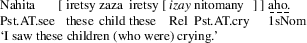

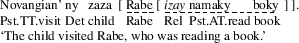

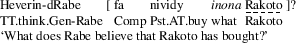

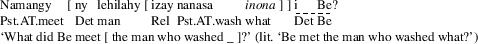

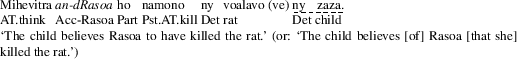

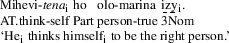

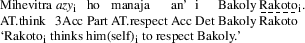

All data in this paper comes from the Merina dialect, which forms the basis for the standard variety of Malagasy. The following abbreviations are used in the glosses: 1ex: 1st person exclusive, 1in: 1st person inclusive, 1s: 1st person singular, 2s: 2nd person singular, 2p: 2nd person plural, 3: 3rd person (singular/plural), Abs: absolutive, Acc: accusative, AT: actor-topic voice, Comp: complementizer, CT: circumstantial-topic voice, Dat: dative, Det: determiner, Erg: ergative, Foc: focus particle, Gen: genitive, Imp: imperative, Irr: irrealis/future, Neg: negative marker, Nom: nominative, Nzn: nominalization, Obl: oblique marker, Part: particle, Pres: present, Prt: participle, Pst: past, Rel: relative marker, Top: topic particle, TT: theme-topic voice.

Another possibility is that the embedded clause is extraposed in (8b), just as in (8a), and the syntactic trigger position is filled by a null expletive, as suggested by an anonymous reviewer. Either way, the embedded clause in (8b) functions as the matrix trigger in the broad sense that its syntactic role (complement of ‘think’) is what determines the voice of the matrix verb.

Nominal and adjectival predicates in Malagasy are not marked for tense (Malagasy is a zero copula language). Nevertheless I assume that nominal and adjectival predicates include a T head and belong to category TP, since their distribution is essentially the same as that of verbal predicates. (Note that in irrealis/future clauses, nominal and adjectival predicates are preceded by the particle ho. I assume that this particle spells out the irrealis/future feature on the T head.) In Sect. 3.2 I suggest that the presence of overt tense inflection is neither necessary nor sufficient for a Malagasy predicate to pattern as finite.

Travis (2006) also argues that the Malagasy trigger is a dislocated topic-like element which originates in a non-argument position and binds an empty category within the predicate phrase, although she identifies that category as pro rather than OP. In support of this analysis, Travis points out a number of structural parallels between the Malagasy trigger-predicate structure and clitic left dislocation structures in Romance.

Orthographic d in an-dRasoa, vangian-dRasoa, etc., reflects a morpho-phonological change whereby n and r merge across a morpheme boundary to become a prenasalized apico-alveolar affricate, written ndr.

In Pearson (2005a) I suggest that genitive and nominative are not in fact distinct m-cases, but rather phonologically bound and free realizations of a single m-case. I set aside this possibility here.

Although every speaker I consulted showed a strong preference for tense matching, one speaker also allowed irrealis marking on the IPVC as a marked option (hence the ?? on (28c) and (29c)). Note that the tense matching pattern found here is not unique to the IPVC construction. Malagasy also has control complements whose tense marking is dependent on the tense of the superordinate clause. Some control verbs (e.g., manaiky ‘agree’) select an embedded clause in the irrealis form, but for other control verbs (e.g., manandrana ‘try’, manomboka ‘begin’) the tense of the embedded clause matches the tense of the control verb. See Paul and Ranaivoson (1998) for an overview of clausal complementation in Malagasy, and Polinsky and Potsdam (2004); Potsdam (2009) for recent discussion of Malagasy control constructions.

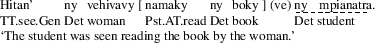

Incidentally, (28a) is grammatical under an irrelevant interpretation where the sentence denotes perception of an individual (‘The woman sees the student who was reading a book’) rather than perception of an event. Under this interpretation, the bracketed constituent is not a clause, but rather a DP within which namaky boky functions as a relative clause modifying mpianatra. The same holds for (28c) and (29b,c). See Sect. 4.2 below for detailed discussion.

Rizzi (1997), from whom I borrow the Fin category, locates FinP below TopP rather than above it. For Rizzi, SpecTopP is the position of left-dislocated topics in Italian, which precede non-finite complementizers (located in Fin) in embedded contexts. However, although I analyze triggers in Malagasy as dislocated topics, I do not assume that they have the same structural status as dislocated topics in Italian; thus the projection I label TopP is presumably not the same as Rizzi’s TopP. Italian topics are optional and stackable, and can be of various categories, whereas in Malagasy every clause includes one and only one trigger, which must be a DP or embedded clause (suggesting that the Malagasy Top head includes an EPP feature and a [D] feature). In addition, dislocated topics in Italian have a contrastive or scene-setting function, whereas the Malagasy trigger is interpreted as the theme in a theme-rheme structure.

Possible cross-linguistic evidence for an Agree relation between Fin and T comes from languages like Irish, where finite complementizers inflect for tense in agreement with the tense on the verb (McCloskey 1996). Assuming the hierarchy of projections in (30), inflected complementizers might result from raising of the Fin head to merge with C.

In Pearson (2001) I suggest that TP-raising in Malagasy is essentially the phrasal movement analog of finite V-raising into the left periphery in languages like Icelandic, which exhibits (both root and embedded) verb-second order. Under the analysis espoused here, TP-raising and finite V-raising would be different reflexes of the same probe-goal relation between the T head and the Fin head. See Pearson (2001) and Travis (2006) for different accounts of why Malagasy exhibits phrasal movement into the C-domain where other languages have head movement.

From this perspective, the contrast between semantically finite clauses (with TP raising) and semantically non-finite clauses (with no TP raising) is reminiscent of what we find in many V-movement languages, where the verb surfaces in a lower head position in non-finite clauses than in finite clauses. For instance, Pollock (1989) shows that infinitives in French are spelled out below negation while finite verbs raise to a position above negation. Likewise in Irish, root clauses and finite embedded clauses have VSO order, while non-finite embedded clauses exhibit SOV or SVO order (depending on dialect) due to the lower position of the verb (Bobaljik and Carnie 1996).

It is likely that a structure like (40b), where ny mpianatra is the thematic object of the perception verb while namaky ny boky functions as a depictive modifier, is also available. Consider (i) below, which shows that ny mpianatra can act as the matrix trigger of a TT clause while namaky ny boky remains inside the predicate phrase (as indicated by the position of the question particle ve). Crucially, (i) and sentences like it express perception of an individual and lack an event perception reading.

-

(i)

The construction in (i) does not provide evidence for or against the existence of trigger-initial clauses, and therefore has no bearing on the question of whether predicate-initial order is derived by predicate raising. For reasons of space, I will set this construction aside and focus on cases where strings like ny mpianatra namaky ny boky can be shown to behave as constituents.

-

(i)

Paul (2000:105) notes that subject and complement clauses headed by fa cannot be pseudo-clefted. It is unclear why this should be. However, pseudo-clefting is possible for other kinds of embedded clauses. Paul (2000:106) gives the following example featuring a pseudo-clefted purpose clause (being an adjunct, it triggers CT voice on the verb in the no-phrase):

-

(i)

-

(i)

This is difficult to verify conclusively, given that there are no agreed-upon tests for VP or vP (remnant) constituents in Malagasy. We might note that while either internal argument of a ditransitive verb can be pseudo-clefted, it is not possible to pseudo-cleft a string consisting of both internal arguments. Likewise either internal argument can act as the trigger of the clause (if it is a DP), but the trigger cannot be a string comprised of both arguments. Such a string would plausibly constitute a VP or vP remnant, assuming a structure for ditransitive predicates along the lines of Larson (1988).

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for providing the examples in (50b,c).

Some speakers I consulted allow (51b) if intsony is preceded and followed by a pause, in which case it presumably acts as a parenthetical element. Absent this intonation, speakers agreed that (51b) is noticeably worse than (51a) or (51c).

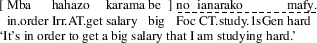

The facts regarding the distribution of izay are not entirely straightforward, however. In apparent contradiction to the judgments in (73), two of the speakers I consulted found sentence (i) below to be fully acceptable. Crucially, though, this sentence does not seem to express direct perception of an event: one speaker who accepted (i) asserted that the children were not necessarily crying when the speaker saw them. I therefore assume that iretsy zaza iretsy izay nitomany is a DP and not an IPVC.

-

(i)

Substantive work remains to be done on the differences between izay relatives and bare relatives. But as far as I have been able to determine, izay relatives can function either as restrictive modifiers, which delimit the referent of the noun, or as appositive modifiers, which merely provide additional information about that referent. Relatives without izay, by contrast, always seem to be restrictive. It is plausible that appositive relatives in Malagasy merge higher than restrictive relatives—e.g., adjoined to DP rather than inside the complement of D—and that (i) contains an example of an appositive relative. Interestingly, whereas proper names in Malagasy cannot be modified by a bare relative (see (59b) above), they can take an izay relative modifier (ii). The contrast between (59b) and (ii) parallels what we find in English and other languages, where proper names can be modified by an appositive relative but not a restrictive relative.

-

(ii)

-

(i)

Thanks to Eric Potsdam for suggesting this test to me, and for providing the data in (80).

An anonymous reviewer speculates that (80a,b) might be ungrammatical not because the wh-phrase occupies a trigger position, but because it is inside an island. Perhaps the wh-phrase must undergo LF-movement to a scopal position in the matrix C-domain but is blocked from doing so because the IPVC that contains it is opaque for A′-extraction. While this is a plausible suggestion, the evidence weighs against such an account. The example in (i) below, from Sabel (2003:233), shows that a wh-phrase with matrix scope can surface inside an embedded clause (provided it occupies a non-trigger position within that clause). Paul and Potsdam (2008) explicitly claim that in-situ wh-phrases in Malagasy do not undergo covert movement and may occur inside islands. In support of this they cite the example in (ii), which is grammatical and receives a matrix question interpretation despite the fact that the wh-phrase is inside a relative clause.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(i)

Here I use reconstruction as a term of convenience. I do not assume that the trigger in (81b) lowers into the scopal domain of the non-trigger subject at LF. A lowering operation of this type is not needed under a derivational approach to binding such as the one I adopt in Sect. 5.1.2 below, where binding relations are established at the point where the antecedent first merges with the term containing the bound DP.

In (82) the IPVC-predicate is introduced by the adverbial samy ‘each’ (constituency tests confirm that samy is part of the predicate and not the IPVC-trigger). Samy often co-occurs with a universal quantifier like tsirairay to enforce a distributive reading.

The definition in (85a) is worded in such a way that if α occupies an A-position at the edge of an XP phase (e.g., the specifier of XP) it can be locally bound by a DP in the next-higher phase, as when the subject of a vP small clause complement is bound by the subject of the higher clause. This is allowed because, in Chomsky’s (2001, 2008) model, the edge of a phase is not spelled out until the next-higher phase has been created.

The matrix subject subsequently raises out of the vP to the specifier of TP to satisfy the EPP feature on T. We must therefore interpret the binding principles such that a pronoun/anaphor α is locally bound by β if (a) α is bound by β, and (b) β is base-merged within the BD for α. This entails that β enters into a binding relation with α as soon as β merges with a term containing α, which happens prior to the point in the derivation where the YP containing α is spelled out (YP is not spelled out until the maximal XP has been created).

If izy in (87a) is instead interpreted in its spell-out position, then izy binds Rakoto and the sentence violates Principle C.

Cf. Kratzer and Selkirk (2007), who argue that the TopP projection in German (which they locate between CP and TP, following Jäger 2001) is a phase. Kratzer and Selkirk suggest that the defining property of phase categories might be that they can “introduce (‘externally merge’) new material to their specifier positions,” rather than simply providing landing sites for movement (2007:114). If the Malagasy trigger is base-merged in the specifier of TopP, as I assume here, then TopP in Malagasy would count as a phase by this definition.

Note that if TopP is a phase, it follows that the TP complement of Top (i.e., the predicate phrase) is spelled out as soon as TopP is created. We might therefore wonder how it is that TP is able to raise subsequently to the specifier of FinP, as required by the predicate-raising analysis adopted here. To allow for this, I will assume that the Phase Impenetrability Condition prohibits sub-extraction from a spell-out domain but does not prohibit the spell-out domain itself from re-merging at a later step in the derivation. Cf. the version of cyclic spell-out proposed by Fox and Pesetsky (2005), where spelling out a YP imposes a linear order on the terminals of YP but does not remove YP from the derivation. Under an approach of this type, there is nothing to prevent YP from undergoing further movement as long as its terminals are not reordered.

An anonymous reviewer points out that if the predicate-raising analysis is correct, the anaphor is not c-commanded by aho in its spell-out position. However, if the structure in (88) is on the right track, then the anaphor is c-commanded by the null operator in SpecTP with which aho is co-indexed. Even if there is no operator, sentences like (90a,b) are unproblematic under the derivational binding theory summarized in (85), according to which the binding relation between the anaphor and its antecedent is established when the antecedent base-merges with the constituent containing the anaphor, before predicate raising takes place.

It is interesting to compare binding in the IPVC construction with binding in the so-called raising to object (RTO) construction, mentioned in Sect. 4.1, where a thematic argument of an embedded clause appears to act as the derived object of the higher verb, separated from the embedded predicate by the particle ho (Keenan 1976; Paul and Rabaovololona 1998). Example (48a) is repeated in (i) below with the derived object italicized. The RTO construction resembles the IPVC construction in terms of word order, though in Sect. 4.1 I noted that they pattern differently with regard to constituency tests. Note also that the embedded verb in an RTO construction is not subject to a tense-matching requirement, but is instead independent of the tense of the higher verb (i.e., the embedded predicate is ‘semantically finite’).

-

(i)

Despite the label raising to object, it is not clear that the ‘derived object’ has undergone A-movement from the embedded clause into the higher clause. In Pearson (2005a) I argue against a raising analysis. Following Paul and Rabaovololona (1998), I suggest that ho realizes the predication head Pr proposed by Bowers (1993), and that Pr projects a PrP small clause selected by the higher verb. The ‘derived object’ base-merges as the specifier of PrP, while the embedded predicate merges as the complement of Pr. This structure is shown in (ii), where the embedded predicate is analyzed as a TP with a null operator in its specifier. To derive the correct interpretation for the sentence, I assume that the DP in SpecPrP binds the null operator.

-

(ii)

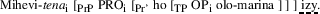

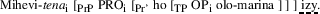

Mihevitra [PrP \(\mathit{an}\mbox{-}\mathit{dRasoa}_{\mathrm{i}}\) [Pr’ ho [TP OPi namono ny voalavo ] ] ] ny zaza.

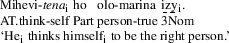

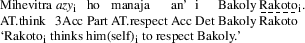

The RTO construction shows apparently contradictory behavior when it comes to binding. The ‘derived object’ can be a simple reflexive bound by the matrix trigger (iii), suggesting that it takes the larger clause as its binding domain. In this respect the RTO construction contrasts sharply with the IPVC construction (cf. (91a)). Paradoxically, however, the ‘derived object’ can also take the form of a pronoun bound by the matrix trigger (iv), implying that its binding domain is the embedded clause. In the latter case the ‘derived object’ seems to pattern with IPVC-triggers. (Examples (iii) and (iv) are taken from Paul and Rabaovololona (1998); note mihevitra + tena becomes mihevi-tena due to a process of pseudo-incorporation where the verb combines with a following bare NP to form a phonological unit.)

-

(iii)

-

(iv)

The binding pattern in (iv) can be accounted for in terms of the structure in (ii) if we assume that PrP complements, like TopP complements, are phases (note that the PrP constituent satisfies the criteria for phasehood proposed by Kratzer and Selkirk 2007; cf. fn. 25). Perhaps the ‘derived object’ receives its semantic role (and is Case-licensed) by forming a chain with the null operator. If so, this would make the specifier of PrP an A′-position. As an A′-element base-merged at a phase edge, the ‘derived object’ would be expected to pattern with embedded triggers with respect to binding (as well as m-case assignment; see Sect. 6.1).

It is less clear how to account for (iii), where the ‘derived object’ appears to be locally bound by the matrix trigger. One possibility is that the ‘derived object’ is optionally introduced as an argument of the higher verb (mihevitra) which controls a null pronominal in SpecPrP:

-

(v)

Clearly more work needs to be done on the structure of RTO clauses before we can determine whether they pose a problem for the theory of cross-clausal A-binding presented here. I leave this as a task for future research.

-

(i)

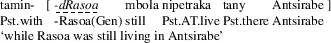

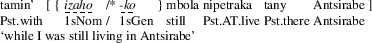

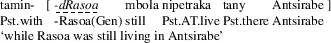

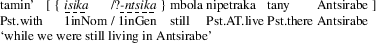

The generalization in (104) may well extend beyond the IPVC construction. Recall from Sect. 3.2 that the preposition amin- ‘with/at’ (tamin- in the past tense) can combine with a trigger-initial clause to form a temporal adjunct (cf. example (33a)). Extending my analysis of IPVCs to this construction, I assume that amin- takes an event-denoting TopP clause as its complement. As discussed in Sect. 2.2, a proper name like Rasoa appears in the genitive (bound) form when selected as a DP complement of amin-: amin-dRasoa ‘with Rasoa’. It turns out that when amin- selects a TopP clause whose trigger is a proper name, that trigger occurs in this same bound form, as shown in (i) below. It thus appears that in the temporal clause construction, as in the IPVC construction, the position of a TopP clause determines the m-case of its trigger, in accordance with (104).

-

(i)

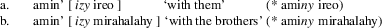

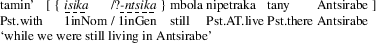

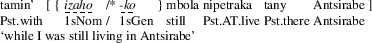

When the trigger of the complement clause is a pronoun, however, the facts are more complex. If the trigger is the first person singular pronoun or the third person pronoun, the genitive forms (-ko and -ny, respectively) are disallowed; instead, the default nominative forms izaho and izy must be used (recall from Sect. 5.2 that the first person pronoun takes the form izaho rather than aho in contexts that call for default m-case):

-

(ii)

I assume that genitive -ko and -ny are disallowed here because they are unstressed enclitics. Note that when amin- selects a first person singular or third person pronoun as its DP complement, the latter will normally take the form of a genitive clitic (amiko/*amin’izaho ‘with me’, aminy/*amin’izy, ‘with him/her’). However, as noted in Sect. 2.2, these pronouns can combine with a modifier to form a larger constituent, in which case the clitic form is disallowed and the pronoun instead appears in the nominative (iii). Plausibly, the clitic forms -ko and -ny are licensed only when the pronoun is sister to the P head. If so, then default nominative overrides genitive in (ii) and (iii) because the P head merges with a larger XP complement which properly contains the pronoun, meaning that the P head and the pronoun do not form a constituent: amin’ [XP izy/izaho … ].

-

(iii)

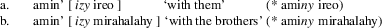

In the case of other pronouns, the genitive form attaches phonologically to the preceding word, but nevertheless behaves as a stress-bearing element (e.g., first person inclusive -ntsika combines with amin- to form àmintsíka ‘with us’). When one of these pronouns acts as the trigger of the complement clause selected by amin-, it appears that either the nominative or the genitive form may occur (iv). Speakers I consulted gave genitive forms, but an anonymous reviewer points out that other speakers strongly prefer the nominative in such examples, and internet searches suggest that the nominative forms occur more often in spontaneous usage. For speakers who require isika in (iv), it could be that the restriction against -ko and -ny extends to all bound pronouns: hence -ntsika is blocked from attaching to amin- by the intervening TopP clause boundary, triggering use of default nominative. For speakers who allow the genitive form in (iv), perhaps bound stressed pronouns (and bound proper names) combine with their hosts post-syntactically, such that tamin- and -ntsika need not form a constituent but must simply be linearly adjacent.

-

(iv)

In the discussion in Sect. 6.1.1, I will leave this issue open and concentrate on the distribution of nominative vs. accusative m-case. If it turns out that a P head can license genitive m-case on a following clause-initial trigger, my account of accusative IPVC-triggers can easily be extended to cover genitive triggers in temporal clauses.

-

(i)

McFadden (2004) and others have taken this idea further by proposing that abstract Case should be eliminated from the theory completely, with the syntactic distribution of DPs captured by appealing to EPP features and other mechanisms. Since my analysis of Malagasy m-case does not bear directly on this question, I will continue to characterize DP licensing in the syntax in terms of the need to check a [uCase] feature.

See McFadden (2004) for a similar view of m-case in German. McFadden argues that marked m-case (accusative, dative, genitive) overrides default nominative just in case the DP receiving m-case appears in the relevant structural configuration(s).

m-case realization is not entirely divorced from [uCase] checking, however. Pesetsky assumes that a categorial feature may be copied onto a DP only in the position where that DP is Case-licensed (2013:73). This ensures that if a DP undergoes EPP-driven movement, its m-case realization will be determined by its derived position rather than its base position. For instance, the subject of an English passive or unaccusative predicate will not be realized as accusative by virtue of being selected by a V head, because its [uCase] feature is not checked until it raises out of the complement of V to a higher position. As for the Malagasy trigger, its [uCase] feature is checked when it base-merges with Top’ to form TopP, as discussed above. We therefore expect that SpecTopP is the position in which the trigger’s m-case realization is determined, which is what I assume here.

In differentiating phases from spell-out domains, I am following the model of cyclic spell-out in Chomsky (2001). Pesetsky (2013) adopts a slightly different approach: he assumes that the entire XP phase (rather than the complement of the phase head X) is a spell-out domain, and that XP is spelled out immediately after the point in the derivation where it merges with a head and feature copying takes place.

The wording in (114a) is modeled closely on Pesetsky (2013:88). I have simplified the formulation by omitting certain technical details which Pesetsky introduces to handle morphological complexities in Russian that have no counterpart in Malagasy. Another difference is that Pesetsky treats that condition in (114b.i) as a restriction on feature copying, rather than incorporating it into the definition of accessibility. Note also that the statement in (114c) is incomplete, since it fails to mention genitive m-case. As discussed in Sect. 2.2, possessors, complements of prepositions, and non-trigger subjects normally take the genitive form, suggesting that genitive realizes the categorial feature of various heads—e.g., the P head, or the T head in the case of a subject sitting in SpecAspP (cf. the bracketed structure in (108b)).

Cf. Bruening (2001) on a similar long-distance agreement construction in the Algonquian language Passamaquoddy. Polinsky and Potsdam cite additional examples of cross-clausal agreement in a number of genetically unrelated languages, including Hindi/Urdu, Chukchi, and Hungarian (though they do not assume that a single analysis will necessarily apply to all these constructions).

In sentences like (122b) and (123), topic movement is covert—that is, the embedded topic magalu(-gon) is spelled out in the canonical object position, within TP, rather than in SpecTopP. However, given cyclic spell-out, I must assume that the embedded topic DP is in the same spell-out domain as the higher verb in order for the φ-features of DP to be realized on that verb. I must therefore assume that an unpronounced copy of the embedded topic merges in the specifier of TopP before the TP is spelled out, and it is this unpronounced copy whose φ-features are copied onto the verb when V subsequently merges with TopP.

I have updated this structure slightly: Guasti assumes that subject agreement is located in an AgrS head, and thus labels the complement of che AgrSP rather than TP.

References

Aldridge, Edith. 2004. Ergativity and word order in Austronesian languages. PhD diss., Cornell University.

Bobaljik, Jonathan, and Andrew Carnie. 1996. A minimalist approach to some problems of Irish word order. In The syntax of the Celtic languages, eds. Robert D. Borsley and Ian Roberts, 223–240. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bowers, John. 1993. The syntax of predication. Linguistic Inquiry 24: 591–656.

Brody, Michael. 2000. Mirror theory: Syntactic representations in perfect syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 31: 29–56.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2001. Syntax at the edge: Cross-clausal phenomena and the syntax of Passamaquoddy. PhD diss., MIT.

Canac-Marquis, Réjean. 2005. Phases and binding of reflexives and pronouns in English, In Conference on Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG05) 12, ed. Stefan Müller, 482–502. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays in minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–155. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta, 133–166. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chung, Sandra. 1998. The design of agreement: Evidence from Chamorro. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1995. The pseudo-relative and ACC-ing constructions after verbs of perception. In Italian syntax and universal grammar, ed. Guglielmo Cinque, 244–276. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cole, Peter, and Gabriella Hermon. 2008. VP raising in a VOS language. Syntax 11: 144–197.

Coon, Jessica. 2010. VOS as predicate fronting in Chol Mayan. Lingua 120: 345–378.

Dahl, Otto C. 1996. Predicate, subject, and topic in Malagasy. Oceanic Linguistics 35: 167–179.

Declerck, Renaat. 1982. The triple origin of participial perception verb complements. Linguistic Analysis 10: 1–26.

Dik, Simon C., and Kees Hengeveld. 1991. The hierarchical structure of the clause and the typology of perception-verb complements. Linguistics 29: 231–259.

Felser, Claudia. 1999. Verbal complement clauses: A minimalist study of direct perception constructions. Vol. 25 of Linguistik Aktuell [Linguistics Today]. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Fox, Danny, and David Pesetsky. 2005. Cyclic linearization of syntactic structure. Theoretical Linguistics 31: 1–46.

Fugier, Huguette. 1999. Syntaxe malgache. Louvain-la-Neuve: Peeters.

Guasti, Maria Teresa. 1993. Causative and perception verbs: A comparative study. Torino: Rosenberg and Sellier.

Guilfoyle, Eithne, Henrietta Hung, and Lisa Travis. 1992. Spec of IP and Spec of VP: Two subjects in Austronesian languages. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 10: 375–414.

Harley, Heidi. 1995. Abstracting away from abstract case. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 25, Vol. 1, 207–221. Amherst: GLSA.

Jäger, Gerhard. 2001. Topic-Comment structure and the contrast between stage-level and individual-level predicates. Journal of Semantics 18: 83–126.

Johannessen, Janne B. 1998. Coordination. New York: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, Kyle. 1991. Object positions. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 9: 577–636.

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Keenan, Edward L. 1976. Remarkable subjects in Malagasy. In Subject and topic, ed. Charles Li, 249–301. New York: Academic Press.

Keenan, Edward L. 1995. Predicate-argument structure in Malagasy. In Grammatical relations: Theoretical approaches to empirical questions, eds. Clifford Burgess, Katarzyna Dziwirek, and Donna Gerdts, 171–216. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Keenan, Edward L. 2000. Morphology is structure: A Malagasy test case. In Formal issues in Austronesian linguistics, eds. Ileana Paul, Vivianne Phillips, and Lisa Travis, 27–48. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Keenan, Edward L. 2008. The definiteness of subjects and objects in Malagasy. In Case and grammatical relations, eds. Greville Corbett and Michael Noonan, 241–261. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Keenan, Edward L., and Maria Polinsky. 1998. Malagasy morphology. In Handbook of morphology, 1st edn., eds. Andrew Spencer and Arnold M. Zwicky, 563–623. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kratzer, Angelika, and Lisa Selkirk. 2007. Phase theory and prosodic spellout: The case of verbs. The Linguistic Review 24: 93–135.

Larson, Richard. 1988. On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 335–391.

Lasnik, Howard, and Mamoru Saito. 1991. On the subject of infinitives. Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 27: 324–343.

Lee, Felicia. 2000. VP remnant movement and VSO in Quiaviní Zapotec. In The syntax of verb initial languages, eds. Andrew Carnie and Eithne Guilfoyle, 143–162. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lee-Schoenfeld, Vera. 2008. Binding, phases, and locality. Syntax 11: 281–298.

Marantz, Alec. 2000. Case and licensing. In Arguments and case: Explaining Burzio’s Generalization, ed. Eric Reuland, 11–30. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Massam, Diane. 1985. Case theory and the projection principle. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Massam, Diane. 2000. VSO and VOS: Aspects of Niuean word order. In The syntax of verb initial languages, eds. Andrew Carnie and Eithne Guilfoyle, 97–116. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Massam, Diane. 2001. Pseudo noun incorporation in Niuean. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19: 153–197.

McCloskey, James. 1996. On the scope of verb movement in Irish. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 14: 47–104.

McFadden, Thomas. 2004. The position of morphological case in the derivation: A study on the syntax-morphology interface. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

Milsark, Gary L. 1977. Toward an explanation of certain peculiarities of the existential construction in English. Linguistic Analysis 3: 1–29.

Paul, Ileana. 1996. The Malagasy genitive, In The structure of Malagasy, vol. 1, eds. Matt Pearson and Ileana Paul. Vol. 17 of UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics, 76–91. Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Linguistics.

Paul, Ileana, ed. 1998. The structure of Malagasy, vol. 2. Vol. 20 of UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics. Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Linguistics.

Paul, Ileana. 2000. Malagasy clause structure. PhD diss., McGill University.

Paul, Ileana. 2001. Concealed pseudo-clefts. Lingua 111: 707–727.

Paul, Ileana. 2004. NP versus DP reflexives: Evidence from Malagasy. Oceanic Linguistics 43: 32–48.

Paul, Ileana. 2009. On the presence versus absence of determiners in Malagasy. In Determiners: Universals and variation, eds. Jila Ghomeshi, Ileana Paul, and Martina Wiltschko, 215–242. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Paul, Ileana. 2017. Reduced structure in Malagasy headlines. Linguistic Variation 17(2).

Paul, Ileana, and Eric Potsdam. 2008. How to sluice in the wh-in-situ language Malagasy. In Chicago Linguistics Society (CLS) 40, eds. Nikki Adams, Adam Cooper, Fey Parrill, and Thomas Weir. Vol. 1, 305–319. Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.

Paul, Ileana, and Lucie Rabaovololona. 1998. Raising to object in Malagasy. In The structure of Malagasy, vol. 2, ed. Ileana Paul. Vol. 20 of UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics, 50–64. Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Linguistics.

Paul, Ileana, and Jeannot Fils Ranaivoson. 1998. Complex verbal constructions in Malagasy. In The structure of Malagasy, vol. 2, ed. Ileana Paul. Vol. 20 of UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics, 111–125. Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Linguistics.

Pearson, Matthew. 1998. Predicate raising and ‘VOS’ order in Malagasy. In The structure of Malagasy, vol. 2, ed. Ileana Paul. Vol. 20 of UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics, 94–110. Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Linguistics.

Pearson, Matthew. 2001. The clause structure of Malagasy: A minimalist approach. Los Angeles: UCLA Dissertations in Linguistics 21.

Pearson, Matthew. 2005a. The Malagasy subject/topic as an A′-element. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 23: 381–457.

Pearson, Matthew. 2005b. Voice morphology, case, and argument structure in Malagasy. In Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA 11), ed. Paul Law, 229–243. Berlin: ZAS Papers in Linguistics.

Pearson, Matthew, and Ileana Paul, eds. 1996. The structure of Malagasy, vol. 1. Vol. 17 of UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics. Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Linguistics.

Pesetsky, David. 2013. Russian case morphology and the syntactic categories. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Polinsky, Maria, and Eric Potsdam. 2001. Long-distance agreement and topic in Tsez. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19: 583–646.

Polinsky, Maria, and Eric Potsdam. 2004. Malagasy control and its theoretical implications. Berkeley Linguistics Society (BLS) 30: 365–376.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1989. Verb movement, Universal Grammar, and the structure of IP. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 365–424.

Postal, Paul. 1974. On raising. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Potsdam, Eric. 2006. More concealed pseudo-clefts in Malagasy and the clausal typing hypothesis. Lingua 116: 2154–2182.

Potsdam, Eric. 2009. Malagasy backward object control. Language 85: 754–784.

Quicoli, A. Carlos. 2008. Anaphora by phase. Syntax 11: 299–329.

Rabenilaina, Roger-Bruno. 1998. Voice and diathesis in Malagasy: An overview. In The structure of Malagasy, vol. 2, ed. Ileana Paul. Vol. 20 of UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics, 2–10. Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Linguistics.

Rackowski, Andrea, and Lisa Travis. 2000. V-initial languages: X or XP movement and adverbial placement. In The syntax of verb initial languages, eds. Andrew Carnie and Eithne Guilfoyle, 117–141. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rasoloson, Janie, and Carl Rubino. 2005. Malagasy. In The Austronesian languages of Asia and Madagascar, eds. Alexander Adelaar and Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, 456–488. London: Routledge.

Ravololomanga, Bodo. 1996. Le lac bleu et autres contes de Madagascar: Contes bilingues malgache-français. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar: Handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Runner, Jeffrey T. 1998. Noun phrase licensing. New York: Garland Publishing.

Sabel, Joachim. 2003. Malagasy as an optional multiple wh-fronting language. In Multiple wh-fronting, eds. Cedric Boeckx and Kleanthes Grohmann, 229–254. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Safir, Kenneth. 1993. Perception, selection, and structural economy. Natural Language Semantics 2: 47–70.

Schütze, Carson. 2001. On the nature of default case. Syntax 4: 205–238.

Travis, Lisa. 2006. Voice morphology in Malagasy as clitic left dislocation, or through the looking glass: Malagasy in Wonderland. In Clause structure and adjuncts in Austronesian languages, eds. Hans-Martin Gärtner, Paul Law, and Joachim Sabel, 281–318. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Zribi-Hertz, Anne, and Liliane Mbolatianavalona. 1999. Towards a modular theory of linguistic deficiency: Evidence from Malagasy personal pronouns. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 17: 161–218.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to several anonymous reviewers, and to Eric Potsdam, Ileana Paul, and audiences at the University of Toronto, BLS 42, and the 15th and 19th meetings of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association, for comments on this research. A special thanks to the following speakers for providing data: Hantavololona Rakotoarivony, Noro Ramahatafandry, Raharisoa Ramanarivo, Vola Hanta Randrianarijaona, and Vololona Rasolofoson. Misaotra betsaka tompoko! Any errors of fact and interpretation are solely my responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pearson, M. Predicate raising and perception verb complements in Malagasy. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 36, 781–849 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9388-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9388-6