Abstract

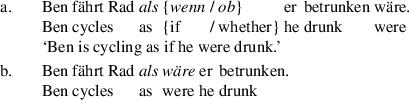

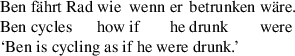

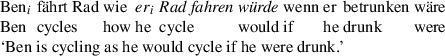

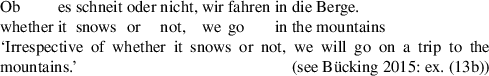

This paper addresses the compositional semantics of hypothetical comparison clauses (= HCCs) in German. HCCs are introduced by either wie (‘how’) or als (‘as’); for example, Ben fährt Rad, {wie wenn er betrunken wäre / als wenn er betrunken wäre / als ob er betrunken wäre / als wäre er betrunken} (‘Ben is cycling as if he were drunk’). I argue for the following hypotheses: (i) Based on an explicit conditional antecedent, HCCs license the interpolation of hypothetical scenarios that give rise to an equivalence relation between entities provided by these scenarios and the given explicit matrix information. (ii) The equivalence relation may hold either between particularized properties (e.g., manners) of hypothetical events and the given matrix event (= V-HCCs), or between hypothetical topic situations and the matrix situation against which the given matrix clause as a whole is evaluated (= S-HCCs). The proposed semantic distinction is traced back to a structural contrast and, thus, is compositionally motivated: V-HCCs relate to the verbal head of the matrix clause, while S-HCCs are non-integrated CP-adjuncts. (iii) Both wie and als lexically encode the relevant mediating equivalence relation; while HCCs with wie allow a regular compositional interpretation in terms of by and large ordinary free relative clauses, als projects rather idiosyncratic semantic (and syntactic) properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

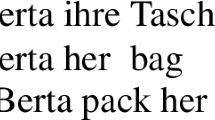

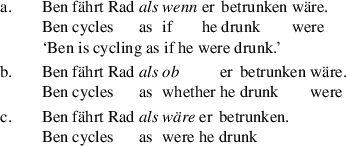

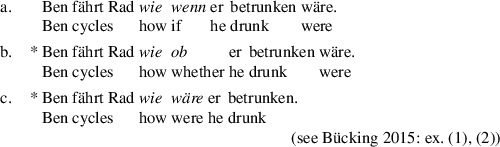

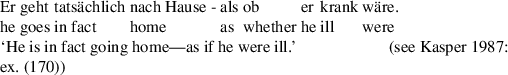

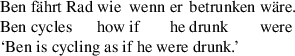

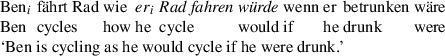

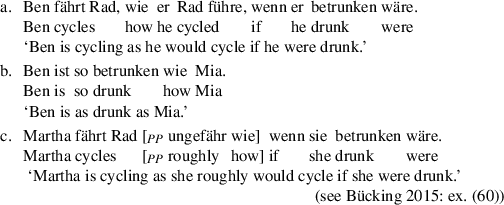

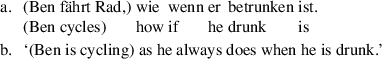

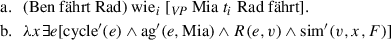

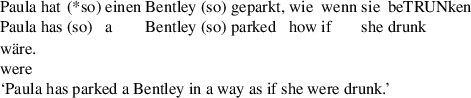

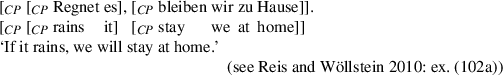

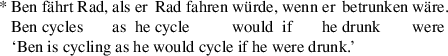

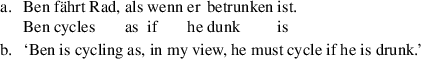

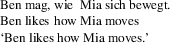

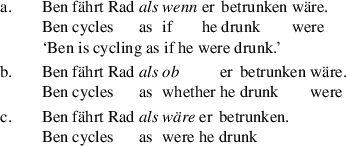

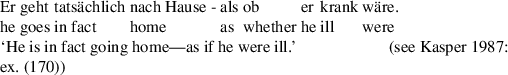

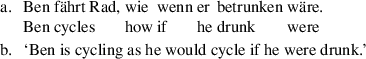

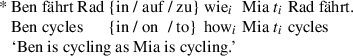

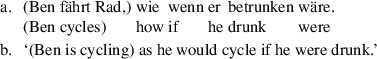

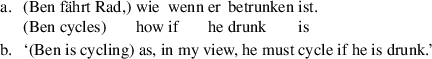

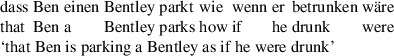

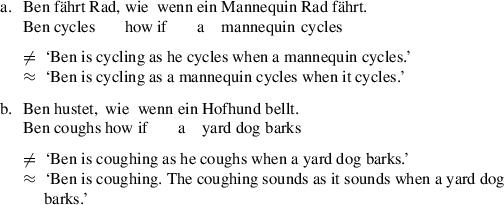

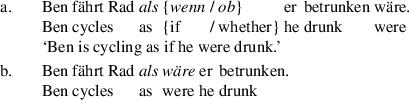

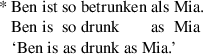

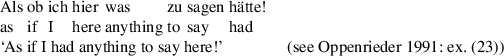

This paper is concerned with the semantics of hypothetical comparison clauses (= HCCs) in German. HCCs appear in four canonical forms: als (‘as’) may be combined with wenn (‘if’), ob (‘whether’), or verb first, as in (1); wie (‘how’) only allows wenn, as in (2).Footnote 1

-

(1)

-

(2)

In recent decades, the syntactic properties of HCCs in their varying forms, their distribution, and their historical development have received much attention (see Kaufmann 1973; Oppenrieder 1991; Hahnemann 1999; Jäger 2010; Pauly 2013; Demske 2014; Bücking 2015). Although their interpretation is not fully ignored (see Kasper 1987 and Eggs 2006 for a corresponding focus), the semantic properties of HCCs have not been discussed in detail. Thus, explicit semantic representations, let alone attempts at deriving them from independently motivated structural components, are still missing. This paper aims at closing this gap and, thereby, providing a considerably refined look at HCCs’ key grammatical and pragmatic traits.

A semantic analysis of HCCs faces the following challenges. For a start, one would like to find out how the conditional antecedent—which is transparent at least in the examples with wie wenn—and the introductory als or wie conspire to produce the peculiar interpretation HCCs have; note, in particular, that HCCs seem to lack a proper consequent. The HCCs in (1) and (2) suggest that Ben is cycling in wiggly lines; they receive a manner interpretation. A first approximation of this reading is given by the rough paraphrase in (3).

-

(3)

Ben is cycling in a way that holds true of his cycling if he is drunk.

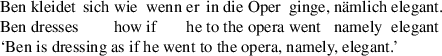

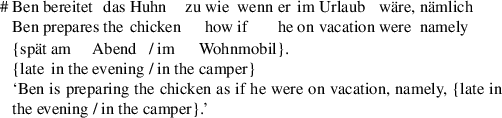

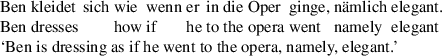

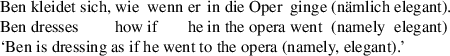

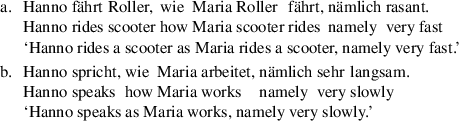

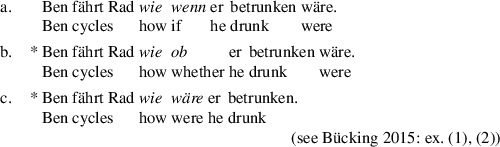

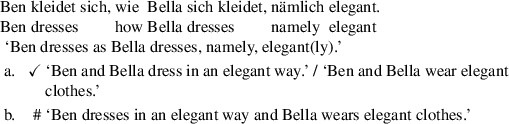

Hence, the analysis of such HCCs ties in with the more general question of what manner modifiers are and how they are compositionally derived. One complication arises from the observation that HCCs also allow what I will call a predicative reading, as, for instance, in (4). The afterthought introduced by nämlich (‘namely’) indicates that the property that is to be inferred from the HCC does not apply to the manner of the dressing, but to the resultant property of the agent’s clothing.Footnote 2

-

(4)

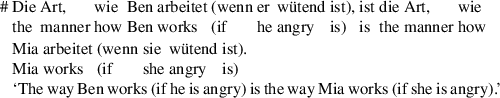

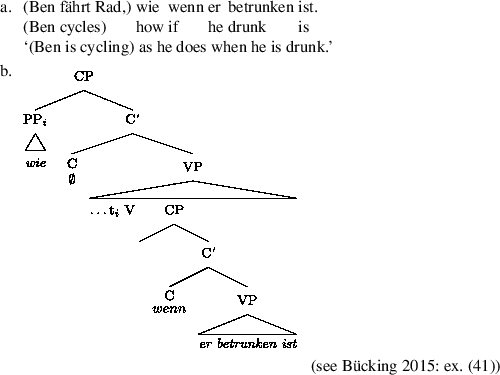

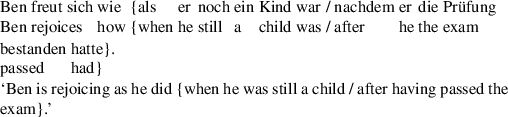

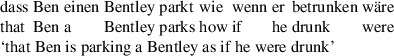

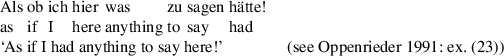

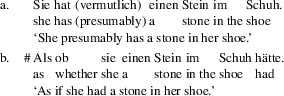

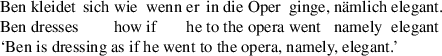

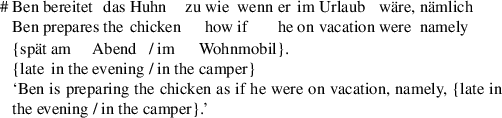

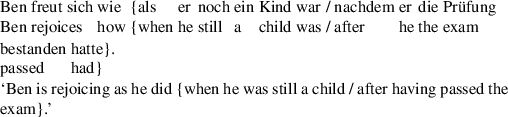

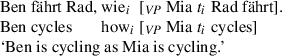

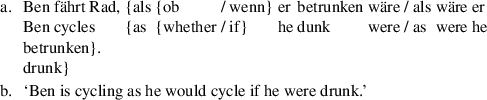

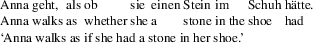

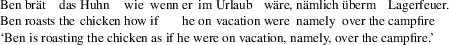

A further desideratum results from the fact that HCCs may relate not only to the verbal projection (= V-HCCs), but also to full sentences, as in (5).

-

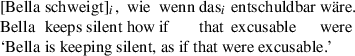

(5)

Such sentential HCCs (= S-HCCs) do not receive a manner or predicative interpretation. Kasper (1987) considers them comments on facts. This characterization calls for an adequate specification; most importantly, it must be clarified to what extent both V-HCCs and S-HCCs share a common core, and which systematic factors may explain the distinctive effects on interpretation.

As will be shown in the upcoming discussion, HCCs introduced by wie are more regular than HCCs introduced by als. I will therefore focus on the composition of wie-HCCs here; a brief outlook on als-HCCs will be given at the end of the paper. In a nutshell, I will argue that the conditional antecedent within wie-HCCs licenses the interpolation of hypothetical scenarios; these, in turn, serve as the basis of a comparison that is mediated by the introductory wie: in V-HCCs, the given matrix event and hypothetical implicit events share equivalent event-internal particularized properties (such as manners or resultant properties); in S-HCCs, the proposed equivalence relation is argued to hold between the matrix topic situation and hypothetical ones. In order to flesh out the composition, I will bring together various independently motivated components—the perspective on modality and conditionals as proposed by Kratzer (1991a,b), an ontology that has events, particularized properties of events and situations at its disposal (see Piñón 2008; Schäfer 2013; Kratzer 2010), and a conception of equivalence in terms of equivalence relative to selected attributes (see Umbach and Gust 2014). The semantic contrast between V-HCCs and S-HCCs will be traced back to different syntactic landing sites as fed by different types of clausal linkage.

While the present paper focuses on specific structures in German, the results have more general implications: for one, the proposal for HCCs might be inspiring for detailed analyses of similar constructions in other languages (obviously, as if in English also introduces hypothetical comparisons). Furthermore, while different types of clausal linkage figure prominently in syntactic research on adverbial clauses, their compositional effects are rarely spelled out in substantial depth. This is particularly true for adverbial clauses that relate to the (lower) verbal domain. Finally, in view of their structural variants, HCCs in German are a challenging test case for the question of how to properly deal with the effects of both ‘constructional’ idiosyncrasies and regular composition at the syntax-semantics interface. The stepwise composition of HCCs with wie will reveal regularities that a ‘constructional’ view on such complex adverbials would miss. HCCs with als, by contrast, will be argued to comply with compositional principles only at the cost of hard-coding their syntactic and semantic idiosyncrasies within the lexicon.

The paper is structured as follows: in Sects. 2 and 3, I will overview the core characteristics of V-HCCs and S-HCCs introduced by wie wenn (‘how if’). In Sects. 4 and 5, the respective composition of V-HCCs and S-HCCs will be spelled out in detail. In Sect. 6, the less regular form types with als (‘as’) will be briefly discussed. Sect. 7 offers a conclusion.

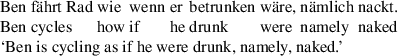

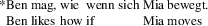

2 V-HCCs with wie

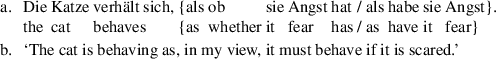

Most scholars agree that V-HCCs typically receive a manner interpretation.Footnote 3 Following Kasper (1987), the conditional antecedent serves to select possible worlds. So the example in (6) (repeating (2a) from above) can be said to be true iff the manner of Ben’s actual cycling “corresponds” (Kasper 1987: 136) to the manner of cycling in the selected possible worlds.

-

(6)

While this approach is intuitively correct, its consequences are barely discussed in more detail. In order to give a refined picture of what is to be captured, I will elaborate on the relevant ontological underpinnings and the role of both the explicit matrix VP and the conditional’s antecedent in the following sections.

2.1 The denotation of V-HCCs from an ontological perspective

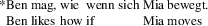

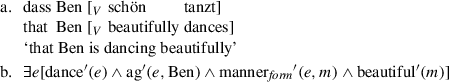

Let us start with a working hypothesis on manner modification in general. A widely accepted intuition is that manner modifiers describe some internal aspect of their target events. One way of specifying this intuition is to conceive of manners as first-order entities, namely, as particularized properties of events; see Dik (1975), Piñón (2008) and Schäfer (2013). The adverbials beautifully and quickly in (7) then describe the form and the speed manner of Ben’s dancing.

-

(7)

Ben is dancing {beautifully / quickly}.

In the following, I will survey the consequences of adopting this perspective for V-HCCs and thereby unfold properties of V-HCCs that have gone largely unnoticed so far.

First, it suggests that V-HCCs and their matrix hosts are not related by comparing eventualities as such, but by comparing their individual manners. This is fully in line with Kasper’s characterization of V-HCCs used above. The example in (6) could convey that the form of Ben’s actual cycling corresponds to the form of his cycling in situations when drunk (for instance, in wiggly lines); alternatively, their speeds could correspond (for instance, very slowly).

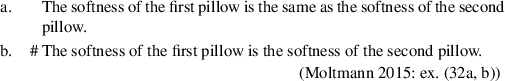

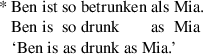

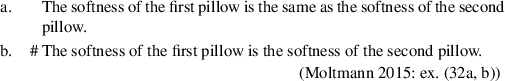

Second, particularized properties are bound to the entities they are properties of. Therefore, an individual’s property cannot be referentially identical to the property of another individual, while it may be equivalent to it; compare the contrast in (8) from Moltmann (2015).

-

(8)

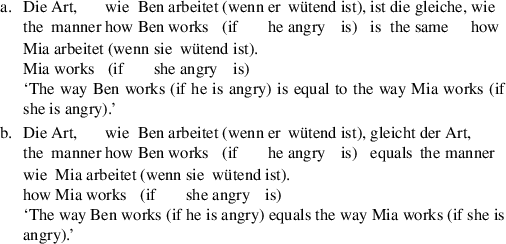

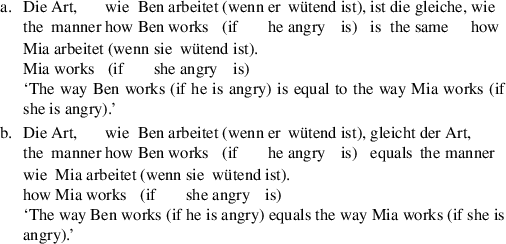

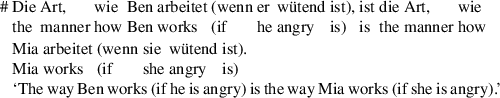

The same holds for manners. Nominal expressions for manners may be said to be equivalent, as suggested by the predicates gleich (‘same’) or gleichen (‘to equal’) in (9), but they may not be said to be referentially identical, as suggested by the identity assertion in (10).

-

(9)

-

(10)

There is a clear consequence for V-HCCs. The manners of the eventualities that are associated with the worlds selected by the conditional antecedent should also be compared to the manner introduced at the matrix level in terms of equivalence.

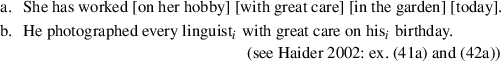

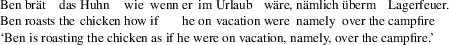

Third, adverbials that locate events as wholes in space and time do not contribute to the internal make-up of an event and, thus, do not specify particularized properties of events. As shown by the deviant afterthoughts in (11), V-HCCs cannot receive corresponding temporal or locative readings.

-

(11)

This supports the assumption that V-HCCs do not compare events as wholes, but specify event-internal properties.Footnote 4 Notably, this constraint is not due to a general conceptual restriction; for instance, one could assert that Ben’s cooking is taking place where it usually takes place during his vacation. So, the limited range of readings for V-HCCs should follow from their semantic composition.

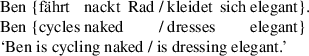

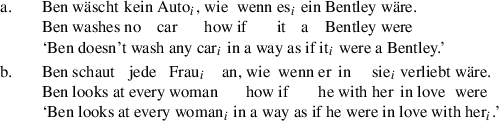

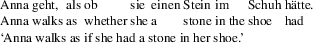

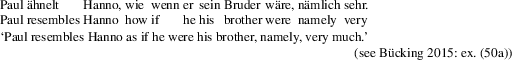

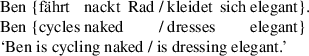

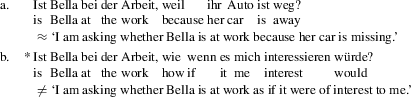

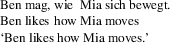

Fourth, as is well known, adjectives in German support depictive and resultative readings, as in (12) (see, for instance, Dölling 2003 and Schäfer 2013).

-

(12)

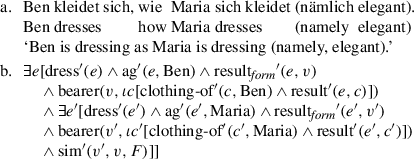

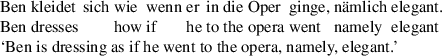

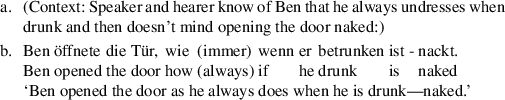

Crucially, the bearers of the relevant particularized properties are not the events as such, but (entities related to) their participants such as Ben himself or his clothing. On the one hand, the adjectives thus do not contribute true manner modifiers, but secondary predications. On the other hand, these predications are not independent from, but entwined with their host events. Accordingly, the depictive naked still describes a mode of cycling, although the property does not arise with the event itself, but its participant. Similarly, the resultative elegant conveys that Ben’s dressing unfolds in such a way—or, ‘mode’—that Ben’s clothing receives the property elegant. Therefore, these depictives and resultatives do not contribute random concomitant, or, resulting states of their host events as wholes, but introduce properties that are made accessible via the event-internal structure. This predicts V-HCCs to also obtain corresponding readings, as borne out by the examples in (13) and (14) (= (4)).

-

(13)

-

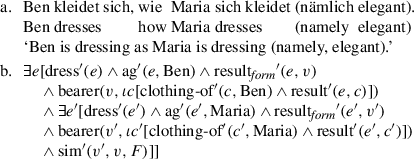

(14)

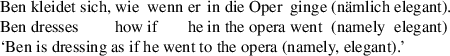

The continuations suggest interpretations on a par with (12) above: example (13) says that Ben’s appearance is equivalent to his hypothetical appearance in situations where he is cycling drunk, and example (14) says that Ben’s resulting clothing is equivalent to his clothing in opera situations.

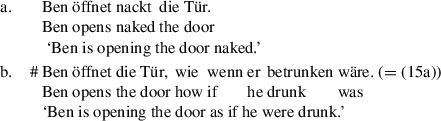

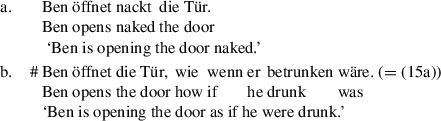

Depictives may also contribute states that accompany the host event in a purely temporal sense and, thus, lack a mode interpretation. Claudia Maienborn (p. c., supported by an anonymous reviewer) pointed out that V-HCCs prohibit this type of interpretation, as shown by (15). This is as expected, given the assumption that V-HCCs specify particularized event-internal properties. Correspondingly, if contextual information supports a mode-oriented interpretation, the V-HCC gets considerably better, as shown by (16).

-

(15)

-

(16)

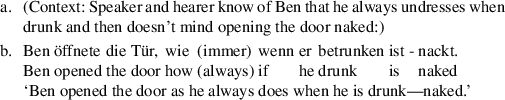

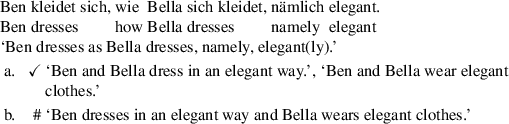

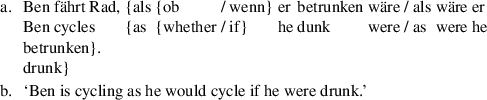

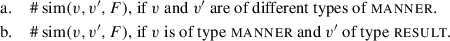

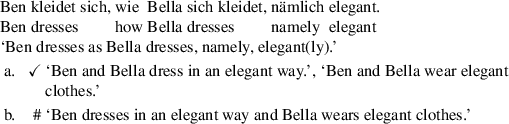

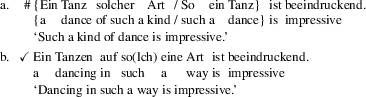

Let me finally note that clausal modifiers such as V-HCCs and their cognate free relatives involve an additional complication. The equivalence analysis argued for above allots separate modifying relations to both the embedded sentence and its matrix host. However, their type of interpretation is not allowed to differ, as shown by (17). (This issue does not arise with adjectives and adverbs, as they only involve one modifying relation.)

-

(17)

Both relations may be resolved uniformly either to a manner or a predicative reading, as in the paraphrases in (17a), while hybrid options are out, as in (17b). Any analysis should capture this principled constraint, underspecification notwithstanding.Footnote 5

2.2 The role of the matrix clause VP

Typically, the matrix VP provides the description of the hypothetical eventuality that hosts the inferred manner. Consider the paraphrase in (18) for (2a) from the introduction, where the conditional’s implicit consequent is made explicit by resorting to the linguistic material given at the matrix level.

-

(18)

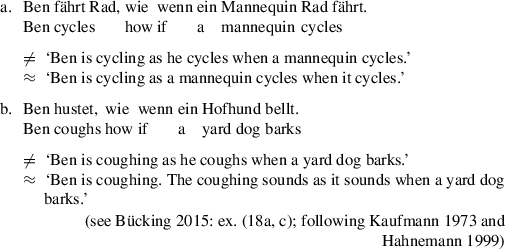

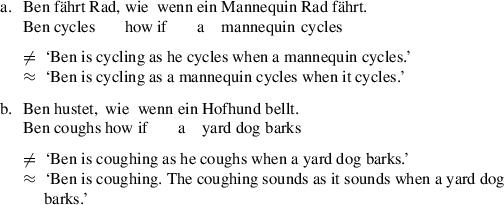

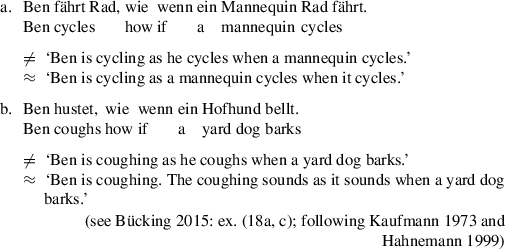

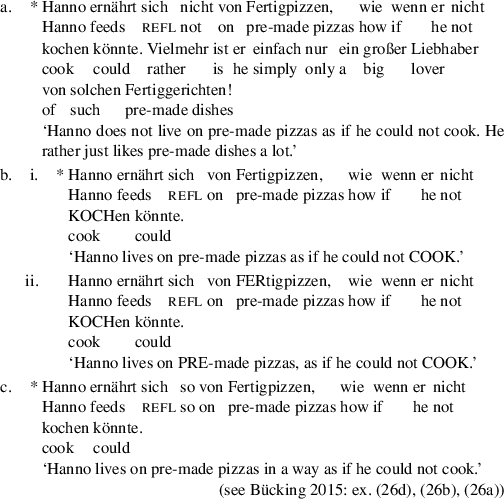

Yet, as shown by Kaufmann (1973), Hahnemann (1999), and Bücking (2015) amongst others, the implicit consequent of V-HCCs does not always correspond to the matrix VP. For instance, in (19a), the implicit and the explicit eventuality involve distinct participants; in (19b), the mediating event description does not surface at all.

-

(19)

The aforementioned scholars exploit these facts to argue against syntactic analyses of V-HCCs in terms of ellipsis. Likewise, the envisaged semantic analysis should not rigidly determine the hypothetical eventualities that host the relevant manner or participant. Instead, the specification should be flexible enough to also be sensitive to context and world knowledge. Notably, the given variability provides another strong argument for the assumption that V-HCCs do not equate events with each other, but rather compare their internal properties.

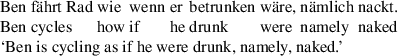

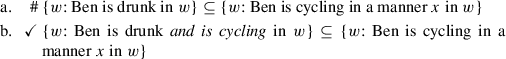

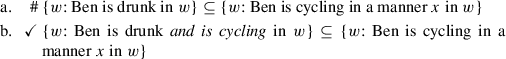

Let me add a further detail that is not explicitly discussed in the literature, but corroborates the distinction between the hosting event descriptions and their internal properties. The introductory example (2a) seems to just say that Ben’s cycling in a specific manner obtains in all worlds in which Ben is drunk; compare the rough approximation in (20). (For ease of presentation, I here assume that the host eventuality is a cycling.)

-

(20)

{w: Ben is drunk in w} ⊆ {w: Ben is cycling in a manner x in w}

However, this is clearly too strong. Intuitively, the specification of a relevant manner should only hold for those worlds where Ben is drunk and is cycling (at the same time), as in (21).

-

(21)

{w: Ben is drunk and is cycling in w} ⊆ {w: Ben is cycling in a manner x in w}

In other words, the semantic set-up should ensure that the host eventuality of the inferred manner is accommodated within the conditional’s restrictor. More details on the role of the conditional will be given in the next section.

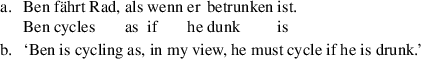

2.3 The role of the embedded conditional antecedent

V-HCCs allow different readings depending on the interpretation of the conditional structure. The following survey provides a systematic approach to this variety in terms of accessibility relations, which, as far as I know, is a new perspective. To foreshadow the analysis, let me note that this variety will be captured in terms of conversational backgrounds as standardly used in modal semantics (see Kratzer 1991a,b). This will render the choice of a particular reading highly context-dependent and comply with the fact that many V-HCCs are formally not bound to one reading. At the same time, factors such as verbal mood, the use of certain adverbials, or the type of V-HCC (see Sect. 6) can be said to systematically constrain the range of potential interpretations.

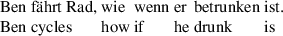

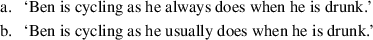

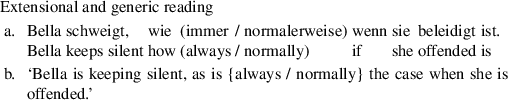

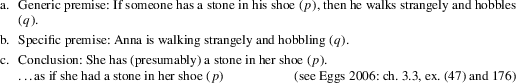

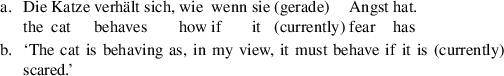

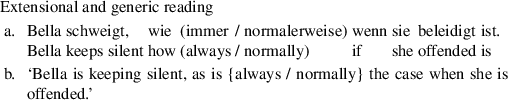

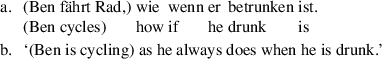

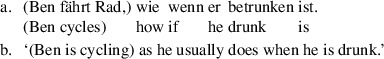

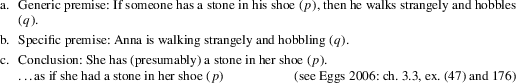

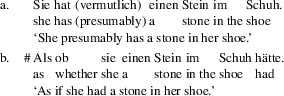

Extensional and generic reading

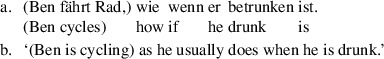

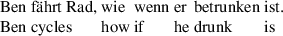

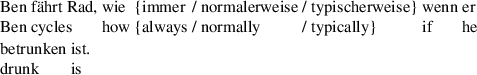

The example in (22) can be paraphrased as in (23a) or as in (23b).

-

(22)

-

(23)

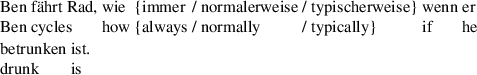

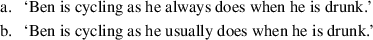

The reading in (23a) is extensional in the sense that it involves universal quantification over situations of Ben’s being drunk and cycling in the actual world; alternative worlds are not made accessible. By contrast, the reading in (23b) is generic in the sense that the universal quantification does not pertain to the actual world, but to normal or stereotypical worlds. That is, those worlds that involve situations, eventualities, and individuals that are normal or stereotypical from the perspective of the actual world are accessible.Footnote 6 Both readings are possible with wie-V-HCCs in the indicative. They can be made explicit by adverbials such as immer (‘always’) for the extensional reading and normalerweise (‘normally’) or typischerweise (‘typically’) for the generic one:

-

(24)

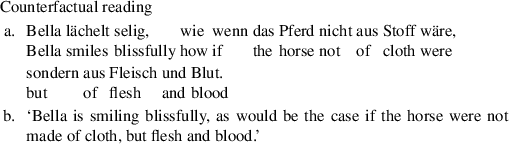

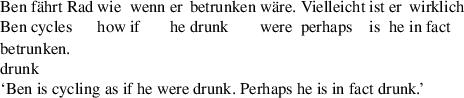

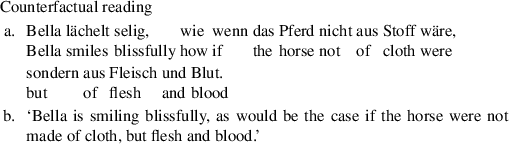

Counterfactual reading

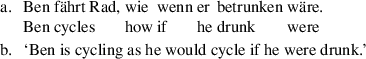

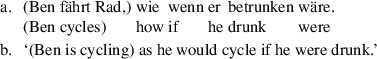

The example in (25a) and its paraphrase in (25b) exemplifies the counterfactual reading.

-

(25)

In terms of the analysis of counterfactuals given in Stalnaker (1968), Lewis (1973), and subsequent work (see for surveys Portner 2009: 247–257 and von Fintel 2011), the universal quantification takes into account only those worlds that are as similar as possible to the actual world, given that the conditional’s antecedent is true. It is licensed by verb forms in the counterfactual subjunctive.

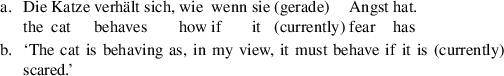

It is fairly controversial what the exact semantic or pragmatic contribution by counterfactual conditionals (as opposed to indicative ones) is and how it arises. However, it is widely agreed that counterfactuals do not semantically entail that their antecedent is false; instead, the corresponding impression is due to a pragmatic implicature. This observation carries over to V-HCCs, as shown by (26), where the relevant implicature is canceled by the context.

-

(26)

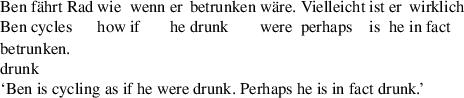

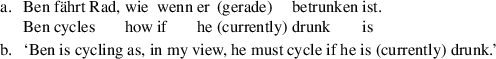

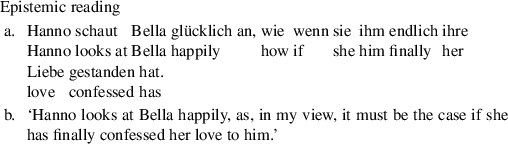

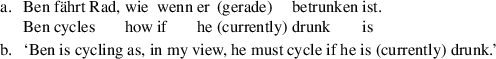

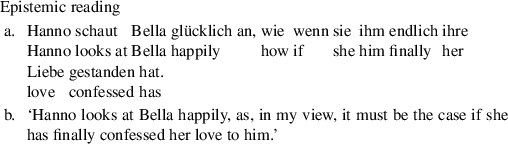

Epistemic reading

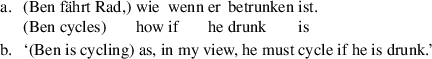

The examples and their paraphrases in (27), (28), and (29) illustrate the epistemic reading. Here, only worlds that are compatible with the speaker’s knowledge and belief are accessible; the finite verb is in the indicative.Footnote 7

-

(27)

-

(28)

-

(29)

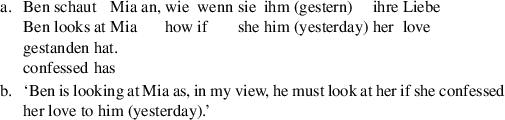

This reading differs from the generic and the extensional ones by not involving regularities of someone’s behavior, but the speaker’s belief given a certain fact in a particular situation. The use of positional temporal adverbials such as gerade (‘currently’) or gestern (‘yesterday’) in the conditional antecedent supports this interpretation.

2.4 Taking stock

I have argued for the following key traits of V-HCCs introduced by wie: (i) V-HCCs do not contribute an identity relation, but a comparison between event-internal particularized properties via equivalence; the relevant eventive anchors are the explicit matrix event and implicit hypothetical events that are constrained by the given conditional antecedent. (ii) The event-internal particularized property can be either borne by the event itself, which yields the canonical manner interpretation, or by (entities related to) the event’s participants, which yields predicative readings. Notably, no crossing of a predicative and a manner interpretation is allowed. (iii) The implicit hypothetical events should invariably feed the restrictor licensed by the given conditional antecedent. They are typically, but not obligatorily, of the same type as the explicit matrix event. (iv) The quantification over hypothetical scenarios is constrained by different kinds of accessibility relations, giving rise to extensional, generic, counterfactual, and epistemic readings.

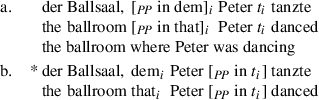

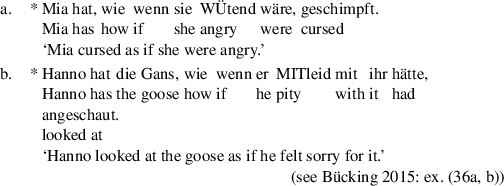

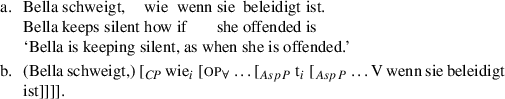

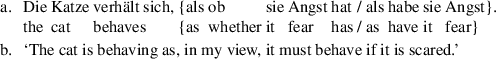

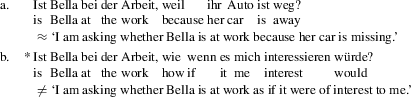

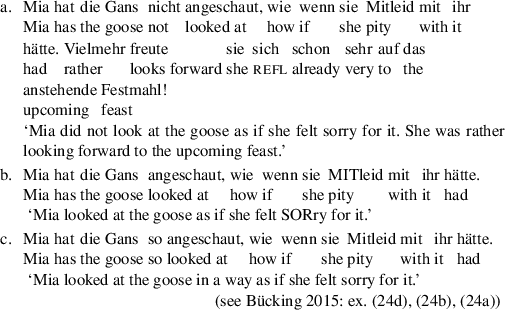

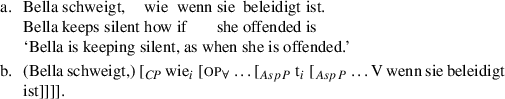

3 S-HCCs with wie

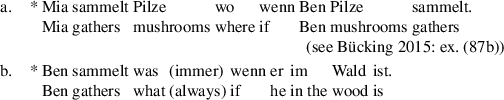

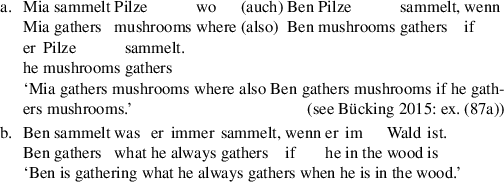

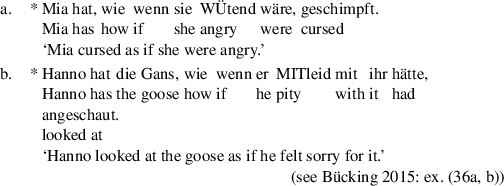

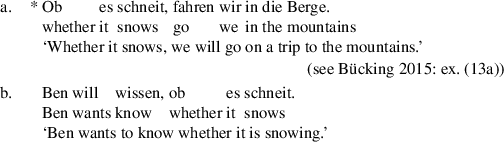

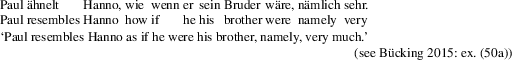

Many scholars distinguish between adverbal hypothetical comparison clauses, that is, V-HCCs as discussed above, and corresponding sentence adverbials, S-HCCs in the following (see Kasper 1987; Hahnemann 1999; Pasch et al. 2003; Fabricius-Hansen 2007; Pauly 2013; Demske 2014; Bücking 2015). The authors, however, only scratch the surface of the semantic underpinnings of the distinction. Pauly, Demske, and Bücking focus on syntactic issues; see below. Hahnemann (1999: 216) states that S-HCCs pattern with ‘sentence comparisons’; Pasch et al. (2003: 622) and, similarly, Kasper (1987: 135, 137) argue that S-HCCs involve the ‘equalization’ or ‘identification of states of affairs.’ But since explicit semantic descriptions are missing, the exact status of such a sentence-based equality or identity remains unclear; for instance, as will become apparent shortly, a naive identity relation between states of affairs falls short of the relevant facts.

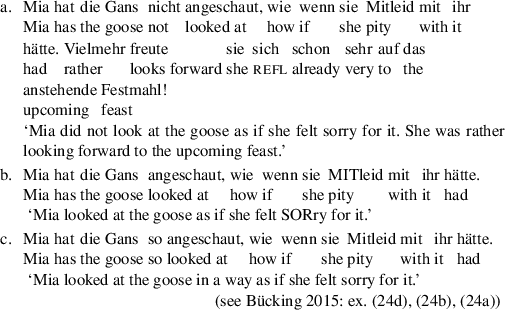

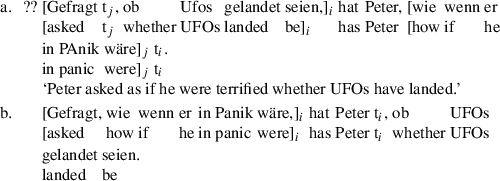

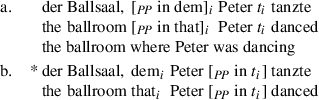

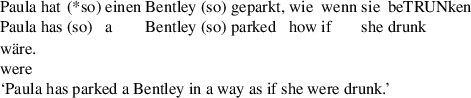

First, any adequate analysis should address structural reasons for the semantic distinction between S-HCCs and V-HCCs. A correlation between form and interpretation is highly likely given that V-HCCs and S-HCCs are linked to their matrix hosts in fairly different ways. Various diagnostics show that V-HCCs occupy integral structural slots of their host sentences while S-HCCs are dependent, but syntactically unintegrated clauses; see Pauly (2013), Demske (2014), and Bücking (2015) for a discussion of HCCs and Reich and Reis (2013) for a general survey of clausal (non-)integration. For instance, S-HCCs cannot be within the scope of sentence negation, have a separate focus-background structure, and prohibit the correlate so in the middlefield of the host clause, as in (30). By contrast, V-HCCs are affected by sentence negation, do not have a separate focus-background structure, and allow so, as in (31).

-

(30)

-

(31)

Hence, while the semantics of V-HCCs should follow from their adjunction to the verbal layer, the semantic contribution of S-HCCs should be linked to their having scope over the matrix proposition as a whole.Footnote 8

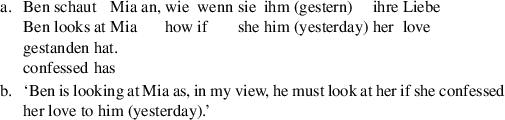

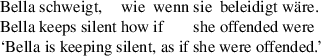

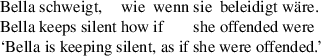

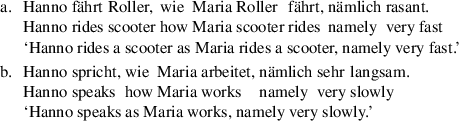

Second, S-HCCs are sensitive to the same accessibility relations as V-HCCs are; compare (32)–(34) for illustration.

-

(32)

-

(33)

-

(34)

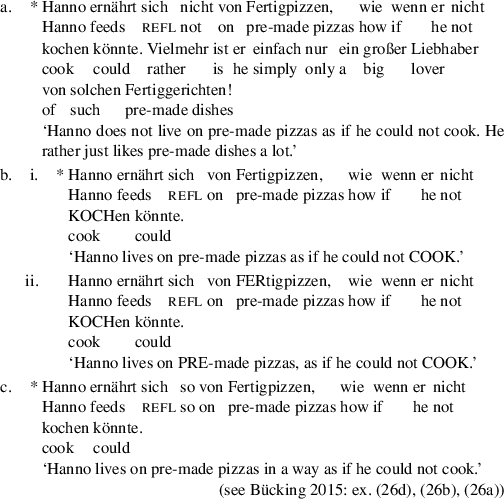

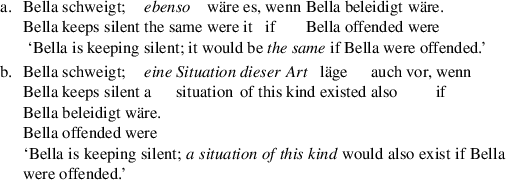

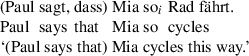

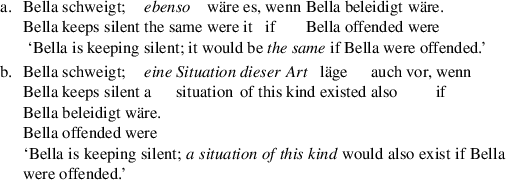

Third, the relationship between the matrix proposition and the S-HCC’s silent consequent is not identity, but equivalence. The counterfactual variant of (32) in (35) and the paraphrases that make its meaning explicit in (36a) and (36b) provide evidence.

-

(35)

-

(36)

Both descriptions show that wie has a bearing on the semantics of S-HCCs that goes beyond identification. Namely, they build on the adverb ebenso (‘the same’) and the nominal predicate eine Situation dieser Art (‘a situation of this kind’), respectively. Both options explicitly point to comparison situations; this is clear evidence for the claim that the situations involved in S-HCCs are not referentially identical to those given at the matrix level, but are equivalent to them in some relevant way. From a compositional perspective, this is a welcome result since the equivalence function associated with wie in V-HCCs is thereby found in S-HCCs as well. Notably, an identifying anaphoric link to propositions or facts is usually established by pro-forms such as das (‘this’/‘that’) or was (‘which’). In fact, S-HCCs allow an additional anaphoric link to the matrix proposition via das, as in (37). This lends further support to the proposed distinction between identification and equivalence.

-

(37)

Taking stock, an appropriate analysis of S-HCCs with wie should capture the following key characteristics: (i) S-HCCs share with V-HCCs both the contribution of an equivalence relation instead of an identity function and the sensitivity to various kinds of accessibility relations. (ii) S-HCCs differ from V-HCCs in not comparing events, but broader situational settings. This difference is rooted in a structural difference: while V-HCCs are integrated into their matrix hosts, S-HCCs are not.

4 Analysis: V-HCCs with wie

In order to flesh out the interpretation of wie-V-HCCs, I will capitalize on the following independently motivated assumptions.

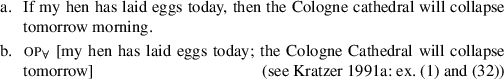

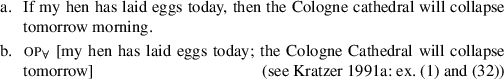

First, the analysis follows the treatment of modals and conditionals in terms of doubly relative modality, as in Kratzer (1991a,b); more recent critical appraisals are provided by Portner (2009) and Hacquard (2011). Kratzer (1991a) interprets modals in relation to two interacting conversational backgrounds that are conceived of as functions from worlds to propositions: the modal base f renders those worlds accessible from a world w that are compatible with certain facts in w. The ordering source g assigns ideals to a world w relative to which the accessible worlds are ordered. Kratzer’s perspective on modality is closely related to her analysis of conditionals in Kratzer (1991b). Crucially, the conditional’s antecedent is said to restrict a modal operator. The antecedent contributes a fact to the modal base and thereby restricts the set of accessible worlds. If the consequent lacks an explicit operator, a silent universal modal (\(=\text{\textsc{op}}_{\forall}\) in the following) is licensed; see (38), which exemplifies an epistemic reading.

-

(38)

Second, the semantic representations will be spelled out according to situation semantics in the sense of Kratzer (1989, 2010); see Portner (2009: 214–220) for the following recapitulation: situations are considered basic entities that can have parts; \(s' \leq s\) stands for ‘\(s'\) is a part of s’. Different types of situations are distinguished: “maximal situations,” not being part of any other situation, are worlds. The example in (39) can be used to introduce further types of situations.

-

(39)

Josephine flew an airplane. (Portner 2009: ex. (268))

For the case at hand, “minimal situations” are the smallest possible situations that contain a flying of an airplane by Josephine. “Exemplifying situations” are possible combinations of minimal situations, be they spatio-temporally connected or not; “counting situations” are maximal spatio-temporally linked exemplifying situations. If Josephine flew an airplane for two hours exactly twice, there are two counting situations. Intuitively, this corresponds to quantification over events in the sense of Davidson (1967) (given some adequate counting criterion). In fact, following Kratzer (2010), I will use event predications such as ‘∃e[fly′(e,x,y)]’ as a handy way of saying that there is a maximal spatio-temporally linked event of flying y by x.

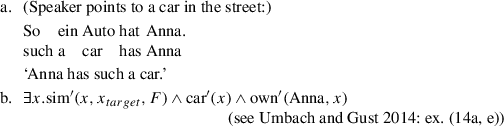

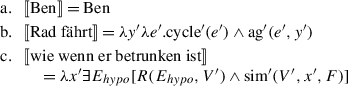

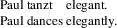

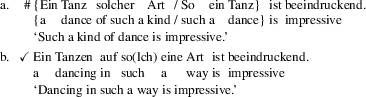

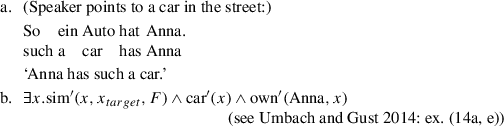

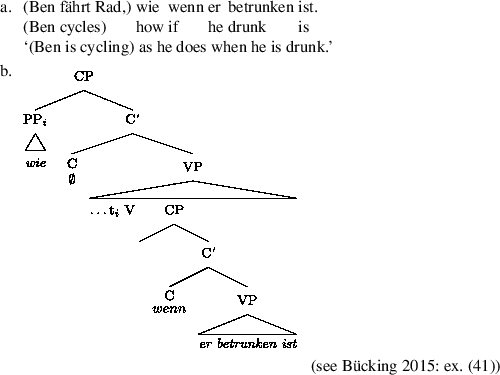

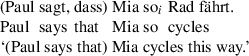

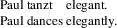

Third, in order to model equivalence relations, the proposal builds upon the analysis of similarity in Umbach and Gust (2014), where similarity is conceived of as equivalence relative to attribute spaces. Umbach and Gust are concerned with the demonstrative so (‘so’ / ‘such’) in examples such as (40a). Its meaning is represented as in (40b).

-

(40)

Their analysis captures that the so-phrase simultaneously functions as a deictic and a modifying expression: the target of the pointing gesture and the relevant DP-referent are not said to be identical, but similar to each other. Furthermore, similarity is relativized to so-called attribute spaces F; this renders similarity sensitive to conceptually based constraints. With regard to adnominal so, for instance, Umbach and Gust argue that only conceptual dimensions that may identify subkinds of the given head noun (that is, fuel type, door number, etc. in the case of car) are relevant. Finally, Umbach and Gust provide a definition of similarity in terms of equivalence relative to attribute spaces F; these attribute spaces are made accessible for truth-conditions via so-called classifying functions \(p^{*}\). Compare the definition in (41).

-

(41)

sim′(x,y,F) iff \(\forall p^{*} \in C(F)\):\(p^{*}(\mu_{F}(x)) = p^{*}(\mu_{F}(y))\)

(see Umbach and Gust 2014: ex. (37))

According to (41), generalized measure functions \(\mu_{F}\) map entities to values in attribute spaces.Footnote 9 Let, for instance, \(\mu_{\text{\textsc{fuel-type}}}\) map x to diesel and y to gasoline. Two entities are similar relative to F iff the application of every classifying function \(p^{*}\) from the set of classifying functions C(F) to the relevant values in the attribute spaces yields the same truth-value. In the given scenario, x and y are not similar relative to the fuel-type attribute space because the classifying functions diesel∗ and gasoline∗ yield different truth-values for them (for instance, \(\mbox{diesel}^{*}(\mu_{\text{\textsc{fuel-type}}}(x)) = \mbox{diesel}^{*}(\text{\textsc{diesel}}) = 1\), whereas \(\mbox{diesel}^{*}(\mu_{\text{\textsc{fuel-type}}}(y)) = \mbox{diesel}^{*}(\text{\textsc{gasoline}}) = 0\)). Notably, this system allows for a flexible specification of the relevant level of granularity: if C(F) contains only combustion engine∗ and, thus, yields a more coarse-grained grid on the attribute space, x and y would count as similar in the given scenario.

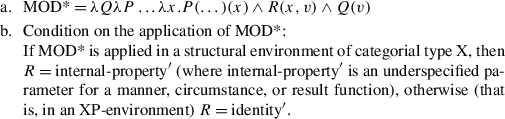

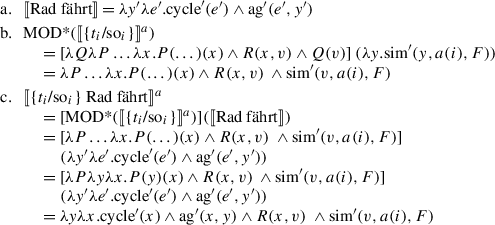

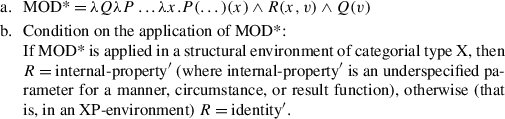

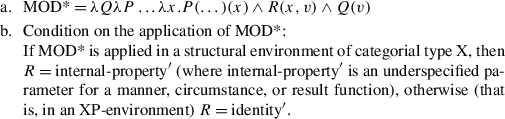

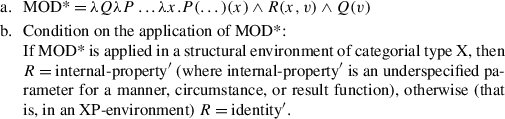

Fourth, and finally, I take the interpretation of modifiers to be sensitive to whether the modifier attaches at the head or the phrasal level. The general idea is that head-adjacent modifiers have access to the internal structure of their targets and, thus, license mediation by conceptual knowledge, while modifiers at the phrasal level relate to their targets holistically; see Maienborn (2001, 2003b), Maienborn et al. (2016), and Schäfer (2013) for different types of modifiers in the verbal domain, and Bücking (2012) for the nominal domain. The aforementioned authors capture this sensitivity in terms of (different versions of) a structure-sensitive modification template. Here, I will rely on MOD* as given in (42).Footnote 10

-

(42)

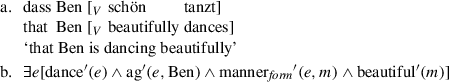

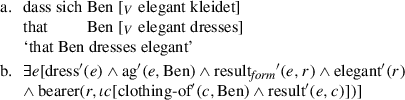

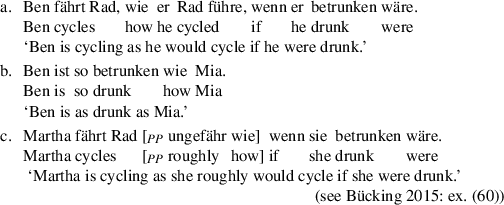

The example in (43a) and its representation in (43b) (adapted from Piñón 2008: ex. (14) and Schäfer 2013: ch. 7, ex. (5, 6)), exemplify the derivation of a manner interpretation via MOD*: a function for form manners maps the dancing to an individual form manner, which, in turn, is described as beautiful.

-

(43)

The resultative reading in (44a) follows form using a result function that maps the dancing to an individual form result, as in (44b). The predication is secondary, as the resultative particularized property is borne by (an entity related to) an event-participant, here, Ben’s clothing as it results from the dressing.

-

(44)

I will now show step by step how to derive the interpretation of V-HCCs from these ingredients. Sect. 4.1 details the internal semantics of V-HCCs, while Sect. 4.2 is concerned with the external link to their matrix clauses.

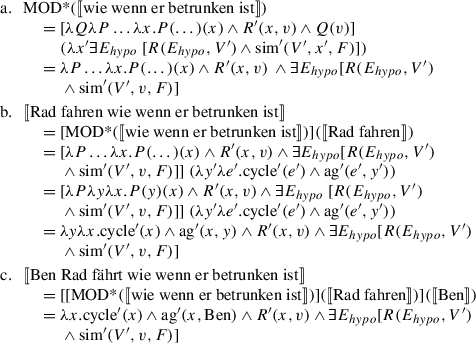

4.1 The internal semantics of V-HCCs: Interpreting wie and the embedded conditional

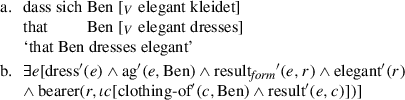

4.1.1 V-HCCs with wie as free relatives

Before putting the compositional machinery to work, a plausible structural basis for interpreting V-HCCs must be determined. Bücking (2015) argues for treating wie-V-HCCs as integrated free relatives. A greatly simplified structure for the wie wenn-clause in (45a) is given in (45b).Footnote 11

-

(45)

Two aspects of this analysis are crucial for deriving the meaning of wie-V-HCCs: first, wie is treated as a moved wh-constituent accompanied by semantic information, analogously to ordinary free relatives. While, for instance, wo (‘where’) bears a spatial meaning, wie can thus be considered the compositional anchor for comparison; see below for details. Second, wie’s VP basis is special: it is (phonologically) empty except for the wenn-clause. This wenn-clause is an integrated postfield constituent that must be licensed by a silent V head; in other words, the explicit wenn-antecedent gives reason to assume a silent consequent. As a consequence, the VP is not lexically given and, thus, to be specified by pragmatic means. Its identification with the given matrix event description (that is, Ben’s cycling in (45)) is certainly a highly plausible option; crucially, however, the structure does not require it.

The following observations (mostly drawn from Bücking 2015) provide independent evidence for the given structure: first, the presumed VP can be made explicit as in (46a); recall as well the examples in (24), where adverbials such as immer (‘always’) are indicative of a silent consequent. Second, as equatives such as (46b) show, the equivalence relation brought in by V-HCCs is not an effect of the structure as a whole, but given by wie in a semantically transparent way. Third, wie can be extended by modifications such as ungefähr (‘roughly’), as in (46c), which supports its phrasal analysis.

-

(46)

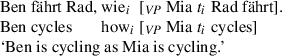

The fourth argument is a bit more intricate: peculiarly, wie-HCCs do not allow verb-first conditional antecedents (recall (2c) from the introduction). At first glance, this comes as a surprise because verb-first antecedents are semantically fairly transparent in contemporary German. However, as argued for by Reis and Wöllstein (2010), they are obligatorily non-integrated and, thus, not related to the matrix VP. Bücking conjectures that verb-first conditionals cannot help identify the silent VP and are, thus, ruled out in HCCs with wie. Notably, this principled explanation for the striking distributional pattern is based on a structure that enforces the identification of a silent verbal head, as in (45b). Conversely, wie can be combined with other adverbial clauses that are potential licensers of a silent VP, such as the temporal ones in (47). While a discussion of their semantics is beyond the scope of this paper, their being possible provides further evidence for a largely regular combinatorics of wie.

-

(47)

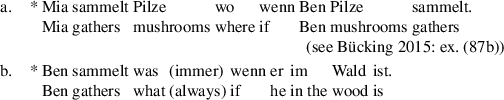

One significant puzzle remains. As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer and also briefly mentioned in Bücking (2015: 303), there are no HCCs introduced by wh-words different from wie, as shown by (48). This is surprising, given that their explicit counterparts in (49) are grammatical.

-

(48)

-

(49)

I suggest the following tentative answer to this challenge: as argued for in Sect. 2.1, wie relates to event-internal particularized properties that do not exist independently from their host events. This intimate relation is a plausible reason for why wie indicates the existence of an event and, thus, can identify a corresponding head. By contrast, wh-words such as wo (‘where’) or was (‘what’) relate to entities that exist independently from the events they contribute to. This independence is a plausible reason for why they cannot license a silent eventive head. I leave a full-fledged account of the relevant constraints to further research. For the time being, the upshot is that only the interplay of an integrated adverbial on the one hand and wie as a marker for particularized properties on the other supports the structure in (45b).Footnote 12

4.1.2 The compositional derivation of the internal semantics of V-HCCs

Given the assumptions made above, the interpretation of the wenn-clause within its matrix consequent is now straightforward; compare (50). The silent VP lacks an explicit operator. Therefore, the antecedent contributes a fact to the modal base of a silent universal modal quantifier. The particular formulation in the spirit of situation semantics builds upon the analysis of quantificational modals in Portner (2009: 274); see Menéndez-Benito (2013) as well.Footnote 13

-

(50)

\([\!\![\mbox{\textsc{op}}_{\forall} \dots \text{V wenn er betrunken ist}]\!\!]^{w,f,g}\)

=1 iff \(\forall w'\)

\(\qquad [ w' \in \mathit{Best}_{g(w)} (\bigcap(f(w) \cup \{\{w'': \exists e'' [ e'' \leq w'' \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e'', \mbox{Ben})]\}\})); \forall e [ e \leq w' \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e, \mbox{Ben}); \exists s \exists e' [e \leq s \wedge e' \leq s \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e')]]]\)

In prose: the fragment in (50) is true in w relative to f and g iff the following holds for all g-best worlds \(w'\) in the set of f-accessible worlds that contain an event of Ben’s being drunk: all events e that are part of \(w'\) and are an event of Ben’s being drunk can be extended to a situation s that contains a V-event.

Notably, the analysis makes a first welcome prediction. As assumed for conditionals based on an implicit operator, a necessity modal is introduced. This is in line with the fact that the various readings V-HCCs give rise to involve universal quantification; see Sect. 2.3 and the following discussion.

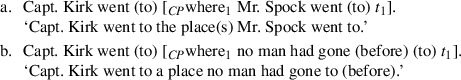

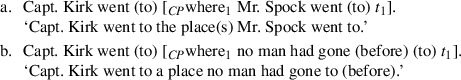

The next step concerns wie’s semantic role. The given structure suggests a composition that follows the interpretation of ordinary free relative clauses. Their semantics is a complicated topic in its own right; see, for instance, Caponigro (2004) or Hinterwimmer (2013). While the discussion in the literature is mostly concerned with DP-like free relatives (which are introduced by, for instance, wer (‘who’) or was (‘what’)), Caponigro also sketches an analysis of PP-like adverbial free relatives such as the ones in (51).

-

(51)

-

(52)

\(\lambda x_{1}\):\(\mbox{place}'(x_{1}). \mbox{went}' (\mbox{to}'(x_{1}))(\mbox{spock})\)

(see Caponigro 2004: ex. (29), (31))

According to the denotation in (52), the free relative CPs in (51) basically denote sets of places where Mr. Spock went. This follows from standard λ-abstraction over the internal variable associated with the trace (motivated by the movement of where, in spirit similar to predicate abstraction as in Heim and Kratzer 1998), and from a presupposition to the effect that \(x_{1}\) must be a place (motivated by the content of where). By using one of two type-shifting rules—namely, “iota” or “existential closure”—this set is mapped either to the maximal place Mr. Spock went to (giving rise to singular or plural definite readings, as in (51a)) or to a non-maximal one (giving rise to an existential reading, as in (51b)).Footnote 14 Caponigro suggests an analogous treatment of free relative clauses with how using manners instead of places; however, this suggestion is not spelled out in detail. I see the following obstacles for an all too simple transfer. First, as argued for in Sect. 2.1, the manner of the matrix event and the manner of the embedded event must not be identical; this, however, would follow from abstracting over a manner variable, analogously to (52) (where it is correct, since, in (51), both the matrix clauses and the free relative clauses involve the very same places). Second, as also argued for in Sect. 2.1, wie-clauses should, besides manner interpretations, license predicative readings, which casts doubt on lexically associating how and wie with manners. Third, Caponigro’s analysis does not pay attention to the verb-adjacency of manner modifiers; it would be desirable to make use of this peculiarity at the syntax-semantics interface. Finally, the proposal involves two silent prepositions—one on top of the base position of where within the free relative clause, another one on top of the free relative as a whole—one argument being that these implicit prepositions can be made explicit (see Caponigro and Pearl 2009 for further discussion). However, (at least) wie in German strictly forbids any explicit preposition. For instance, (53) with a preposition on top of the free relative clause is clearly ungrammatical.

-

(53)

This observation speaks against an application of Caponigro’s syntactic structure to German wie and argues in favor of an approach with an inherently prepositional wh-pronoun (as assumed for wie in the parsimonious structure given in (45b)).

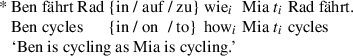

What could an alternative analysis for examples such as (54) look like?

-

(54)

I consider wie a plausible lexical anchor for equivalence. Accordingly, I assume that wie, in its base position, introduces a predicate of equivalence as in (55), which denotes the set of y that are equivalent to some assignment-dependent entity a(i). Note that the same analysis can plausibly be given for wie’s deictic counterpart in (56).

-

(55)

\([\!\![\mbox{wie}_{i} / \mbox{so}_{i}]\!\!]^{a} = \lambda y. \mbox{sim}'(y, a(i),F)\)

-

(56)

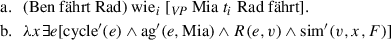

This captures without further ado the PP-like predicate interpretation of wie’s base and so, and enables the regular application of MOD*, as shown by (58) for (57). Since wie and so are projected in a V-adjacent position, MOD* licenses the introduction of a free variable v that is linked to the V-event via R. The integration of the subject and the existential binding of the event argument (including its substitution by the more transparent variable e) yield (59).

-

(57)

[ VP Mia {\(t_{i}\)/so i } Rad fährt]

-

(58)

-

(59)

∃e[cycle′(e)∧ag′(e,Mia)∧R(e,v)∧sim′(v,a(i),F)]

In the deictic variant, the assignment-dependent entity a(i)—that is, the entity of comparison—cannot be subject to local binding, but must be taken from the extra-linguistic context. For instance, v could be said to be equivalent to the manner of an event the speaker is pointing to. With the free relative clause, however, the assignment-dependent entity is sensitive to the λ-abstraction that is triggered by the moved binding relative pronoun; namely, the assignment-dependent entity must be identified with the λ-abstracted variable (see the Predicate Abstraction Rule in Heim and Kratzer 1998: 186). As a result, the whole free relative in (60a) receives the denotation in (60b).

-

(60)

Notably, the syntactic movement pertains to wie as a whole while the semantically relevant abstraction affects only one part of its meaning, namely, the entity of comparison; correspondingly, the equivalence predication is interpreted in situ. I consider this dissociation not particularly surprising, given that pronominal prepositional phrases are quite generally subject to ‘pied-piping’ in German; see, for instance, (61a) where movement includes the preposition although the semantics would need its interpretation in situ, as in the ungrammatical counterpart in (61b).

-

(61)

For reasons of space, I will not be able to discuss the syntax-semantics interface of pied-piping in German; see Sternefeld (2006: 395–408) for its structural analysis within a feature-driven framework. I will not venture either upon an appropriate semantic and/or syntactic decomposition of wie into a component for the equivalence relation and a component for the entity of comparison (this is needed for a parallel analysis to (61a), where the locative relation and the location are decomposed into a preposition and a determiner phrase). However, the analogy should suffice to indicate that the proposed semantic composition is not ad hoc.

The analysis avoids the problems of Caponigro’s suggestion: Since v is related to the given event via R, the resulting logical form does not unequivocally settle a manner interpretation (see the next section for the specification of R). Moreover, the compositional anchor x for linking the free relative clause to the matrix VP is not said to be identical to v, but only equivalent to it. Note as well that the resulting predicate denotation is straightforwardly amenable to a second use of MOD* at the matrix level (this will be spelled out in more detail in the next section).Footnote 15

The analysis of V-HCCs with wie is now straightforward. Since the structure of V-HCCs given in (45b) is analogous to that of ordinary free relatives, their semantics may unfold in the same way; compare (62): wie’s base is associated with a predicate of equivalence, introducing the relation sim. While the head-adjacent base position triggers integration via MOD*—that is, the introduction of a free variable v that is linked to the silent V-event via R—the wh-movement licenses λ-abstraction over sim’s second argument x. There is only one additional complication: as argued for above, V-HCCs come with a quantificational structure triggered by the conditional antecedent; therefore, one has to decide which part of the VP goes to the restrictor and which part goes to the nuclear scope. I assume that moving wie warrants that the whole silent VP, except for the contribution made by the modifying equivalence relation, is background information; this licenses its accommodation within the restrictor of the modal and yields the copies of 〚…V〛 in the restricting parts. The corresponding events then join the respective antecedent event by sum formation.

-

(62)

\([\!\![\mbox{wie}_{i}\ \text{\textsc{op}}_{\forall} \dots \text{t}_{i}\ \text{V wenn er betrunken ist}]\!\!]^{w,f,g}\)

\(\quad {}=\lambda x. \forall w' [ w' \in \mathit{Best}_{g(w)} (\bigcap(f(w) \cup\{\{w'': \exists e'' \oplus e''' [ e'' \oplus e''' \leq w'' \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e'', \mbox{Ben}) \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e''')]\}\})); \, \forall e \oplus e' [ e \oplus e' \leq w' \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e, \mbox{Ben}) \wedge [\!\![\dots \mbox{V} ]\!\!](e'); \exists s \exists e'''' [ e \oplus e' \leq s \wedge e' = e'''' \wedge [\!\![\dots \mbox{V} ]\!\!](e'''') \wedge R(e'''',v)\wedge \mbox{sim}' (v,x,F)]]]\)

In prose: the V-HCC in (45a) denotes—relative to w, f, and g—the set of x so that the following holds for all g-best worlds \(w'\) in the set of f-accessible worlds that contain an event of Ben’s being drunk plus a V-event: all events \(e \oplus e'\) that are part of \(w'\) and are an event of Ben’s being drunk plus the V-event can be extended to a situation s where x is equivalent to some v that is linked to this very V-event via R.

The resulting logical form has two crucial positive ramifications: it predicts that the underspecified V-event forms a part of the operator’s restriction. This is as desired; recall (with a specification of x to a manner) the greatly simplified contrast in (63), repeated from (20) and (21) above:

-

(63)

What is even more important, the logical set-up facilitates an easy account of the various readings of V-HCCs: they simply follow from different assignments to the conversational backgrounds g and f.

The extensional reading is repeated in (64):

-

(64)

It is characterized by the fact that no alternative worlds are involved. This can be captured by letting f be a totally realistic conversational background, that is, a background that pairs every world with exactly those facts that describe the respective world completely. Accordingly, ⋂f(w)={w}, which renders the actual world w the only accessible one; trivially, then, w is also the g-best world. The logical form in (62) thereby boils down to (65), which provides an adequate description of the extensional reading.

-

(65)

\([\!\![\mbox{wie}_{i} \text{\textsc{op}}_{\forall} \dots \mathrm{t}_{i}\ \text{V wenn er betrunken ist}]\!\!]^{w}\)

\(\null\quad =\lambda x.\forall e \oplus e' [ e \oplus e' \leq w \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e, \mbox{Ben}) \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e'); \exists s \exists e'''' [ e \oplus e' \leq s \wedge e' = e'''' \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e'''') \wedge R(e'''',v)\wedge \mbox{sim}' (v,x,F)]]\)

In prose, the V-HCC in (64) denotes—relative to w—the set of x so that the following holds for w: all events \(e \oplus e'\) that are part of w and are an event of Ben’s being drunk plus a V-event can be extended to a situation s where x is equivalent to some v that is linked to this very V-event via R.Footnote 16

The generic reading, repeated in (66), involves a relativization to normal worlds with normal entities.

-

(66)

This can be modeled by combining an empty modal base with a stereotypical ordering source. Such a \(g_{\mathit{stereotype}}\) prefers worlds with situations and entities that are as normal as possible from the perspective of the actual world. The corresponding V-HCC then receives the representation in (67).

-

(67)

\([\!\![\mbox{wie}_{i}\ \text{\textsc{op}}_{\forall} \dots \text{t}_{i}\ \text{V wenn er betrunken ist}]\!\!]^{w,g_{\mathit{stereotype}}}\)

\(\null\quad {}=\lambda x. \forall w' [ w' \in \mathit{Best}_{g_{\mathit{stereotype}}(w)} (\bigcap(\{\{w''\,\, {:}\, \exists e'' \oplus e''' [ e'' \oplus e''' \leq w'' \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e'', \mbox{Ben}) \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e''')]\}\})); \forall e \oplus e' [ e \oplus e' \leq w' \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e, \mbox{Ben}) \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e'); \exists s \exists e'''' [ e \oplus e' \leq s \wedge e' = e'''' \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e'''') \wedge R(e'''',v)\wedge \mbox{sim}' (v,x,F)]]]\)

In prose, the V-HCC in (66) denotes—relative to w and \(g_{\mathit{stereotype}}\)—the set of x so that the following holds for all worlds \(w'\) in the set of worlds that contain an event of Ben’s being drunk plus a V-event so that \(w'\) is most normal from the perspective of w: all events \(e \oplus e'\) that are part of \(w'\) and are an event of Ben’s being drunk plus the V-event can be extended to a situation s where x is equivalent to some v that is linked to this very V-event via R.

In (68), the counterfactual reading is reproduced.

-

(68)

As said above, I follow the Stalnaker-Lewis viewpoint that counterfactuals render accessible only those worlds that are as similar as possible to the actual world given that the antecedent is true. Within Kratzer’s (1991b) framework, such a reading follows from an empty modal base f and a totally realistic ordering source g. For the case at hand, this yields the interpretation in (69). As desired, only worlds are considered that are maximally similar to the actual world while entailing the antecedent plus its accommodated V-event.

-

(69)

\([\!\![\mbox{wie}_{i}\ \text{\textsc{op}}_{\forall} \dots \text{t}_{i}\ \text{V wenn er betrunken w\"{a}re}]\!\!]^{w,g_{\mathit{totally}\text{-}\mathit{realistic}}}\)

\(\null\quad {}=\lambda x. \forall w' [ w' \in Best_{g_{totally\text{-}realistic}(w)} (\bigcap(\{\{w'': \exists e'' \oplus e''' [ e'' \oplus e''' \leq w'' \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e'', \mbox{Ben}) \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e''')]\}\})); \forall e \oplus e' [ e \oplus e' \leq w' \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e, \mbox{Ben}) \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e'); \exists s \exists e'''' [ e \oplus e' \leq s \wedge e' = e'''' \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e'''') \wedge R(e'''',v)\wedge \mbox{sim}' (v,x,F)]]]\)

In prose, the V-HCC in (68) denotes—relative to w and \(g_{totally\text{-}realistic}\)—the set of x so that the following holds for all worlds \(w'\) in the set of worlds that contain an event of Ben’s being drunk plus a V-event so that \(w'\) is most similar to w: all events \(e \oplus e'\) that are part of \(w'\) and are an event of Ben’s being drunk plus the V-event can be extended to a situation s where x is equivalent to some v that is linked to this very V-event via R.

Notably, the fact that the counterfactual reading of V-HCCs depends on verb forms in the counterfactual subjunctive follows from an independent assumption: the explicit antecedent with a verb form in the counterfactual subjunctive correlates systematically with a silent operator that corresponds to would and, thus, triggers the conversational backgrounds characteristic of the counterfactual reading.

The epistemic reading is repeated in (70).

-

(70)

The crucial dependence on the speaker’s knowledge and belief follows from assuming an epistemic modal base and a doxastic ordering source. This is exemplified in (71).

-

(71)

\([\!\![\mbox{wie}_{i}\ \text{\textsc{op}}_{\forall} \dots \text{t}_{i}\ \text{V wenn er betrunken ist}]\!\!]^{w,f_{epistemic},g_{doxastic}}\)

\(\null\quad {}=\lambda x. \forall w' [ w' \in \mathit{Best}_{g_{doxastic}(w)} (\bigcap(f_{epistemic}(w) \cup \{\{w'': \exists e'' \oplus e''' [ e'' \oplus e''' \leq w'' \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e'', \mbox{Ben}) \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e''')]\}\})); \forall e \oplus e' [ e \oplus e' \leq w' \wedge \mbox{drunk}'(e, \mbox{Ben}) \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e'); \exists s \exists e'''' [ e \oplus e' \leq s \wedge e' =\, e'''' \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e'''') \wedge R(e'''',v)\wedge \mbox{sim}' (v,x,F)]]]\)

In prose, the V-HCC in (70) denotes—relative to w, \(f_{epistemic}\), and \(g_{doxastic}\)—the set of x so that the following holds for all worlds \(w'\) so that \(w'\) is closest to the beliefs of the speaker in w, given that \(w'\) is in the set of worlds that contain an event of Ben’s being drunk plus a V-event and are compatible with the knowledge of the speaker in w: all events \(e \oplus e'\) that are part of \(w'\) and are an event of Ben’s being drunk plus the V-event can be extended to a situation s where x is equivalent to some v that is linked to this very V-event via R.

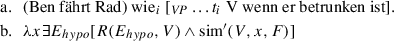

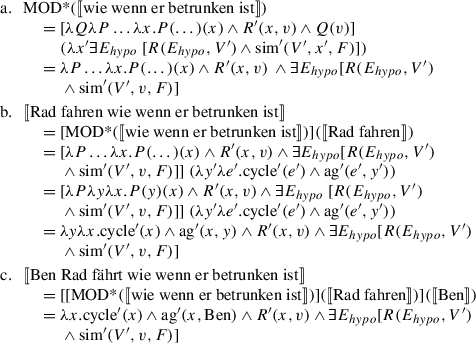

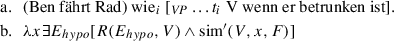

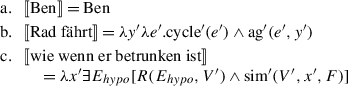

This section has shown that the internal semantics of V-HCCs can be derived in a fairly regular way. The derivation takes seriously the equivalence relation contributed by the wh-pronoun wie and the effects that result from moving it out of a silent consequent. Furthermore, the explicit conditional antecedent licenses a universal operator that renders V-HCCs sensitive to conversational backgrounds and thereby accounts for their different readings in a systematic fashion. For ease of presentation, I simplify this interim result; see the representation in (72b) for (72a). Essentially, \(E_{\mathit{hypo}}\) abbreviates the contribution made by the conditional structure (including the explicit antecedent) and its implicit modalization. So, (72b) says in prose that the V-HCC denotes a set of x so that x is equivalent to all variables V that are linked to hypothetical events \(E_{hypo}\).Footnote 17

-

(72)

As desired, the representation is fully analogous to the one for ordinary free relative clauses except for not yet specifying the relevant events \(E_{hypo}\); compare (72) to (73a) and its representation in (73b) (repeated from (60) above).

-

(73)

The next derivational step comprises the integration of V-HCCs within their matrix hosts.

4.2 The external semantics of V-HCCs: Linking V-HCCs to the matrix clause

4.2.1 On the syntactic backbone for compositionally integrating V-HCCs

While previous research on HCCs widely agrees upon the fact that V-HCCs are integrated within their matrix hosts (see the contrast between S-HCCs and V-HCCs discussed in Sect. 3 above), their exact integration site is not determined in detail. From a compositional perspective, however, such details are important. Crucially, manner and predicative readings of modifiers depend on a free variable that mediates between the modifier and the verbal event; according to MOD*, such a mediation is licensed only if the modifier targets the verbal head. Therefore, V-HCCs should not relate to some higher level of the (extended) verbal projection of the matrix clause, but to the verbal head itself, as in (75) for (74).

-

(74)

-

(75)

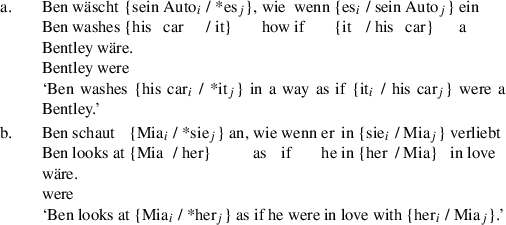

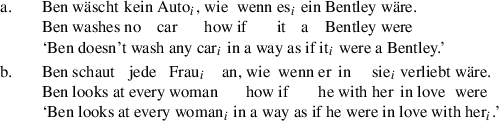

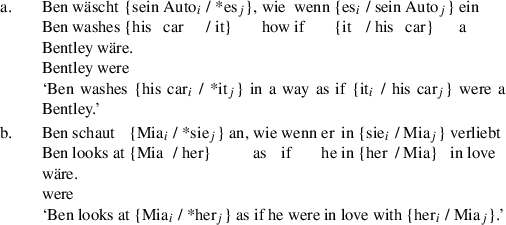

In fact, there is good independent evidence for such a configuration (see, for instance, Frey and Pittner 1998, Maienborn 2001, or Frey 2003 for a general introduction to base positions of adverbials in German and to syntactic tests to identify them). For one, both variable binding, as in (76), and principle-C effects, as in (77), indicate that V-HCCs project below the object. The quantifiers kein Auto (‘no car’) and jede Frau (‘every woman’) can bind a variable in V-HCCs, which requires that they c-command the respective V-HCC. In turn, independently referring terms such as sein Auto (‘his car’) and Mia are not allowed to be c-commanded by co-referential expressions according to binding principle C.

-

(76)

-

(77)

Moreover, if V-HCCs are accompanied by a correlative pronoun in the middlefield, this pronoun must be closer to the verb than the object, as in (78).

-

(78)

Examples with (remnant) topicalization such as (79) suggest as well that V-HCCs are adjacent to the verbal head. Accordingly, (79a) is deviant because the topicalization yields an unbound trace whereas (79b) is fine because it does not involve a binding violation.Footnote 18

-

(79)

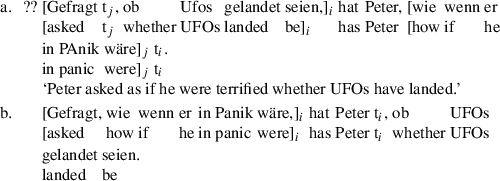

In evaluating these sentences, one has to keep in mind that the relevant HCCs should be manner adverbials here; this correlates with the whole sentences having only one focus-background structure and, thus, only one main accent. If, by contrast, the HCCs were treated as separate non-integrated S-HCCs, the complex sentences would receive two main accents and become grammatical; of course, no binding violation may arise here. Compare the S-HCC variant of (79a) in (80) for illustration: it does not contribute a manner description, but roughly says that asking about UFOs is reasonable for Peter in situations where he is panicking.

-

(80)

[Gefragt, ob UFOs gelandet seien,] i hat Peter t i , [wie wenn er in PAnik wäre].

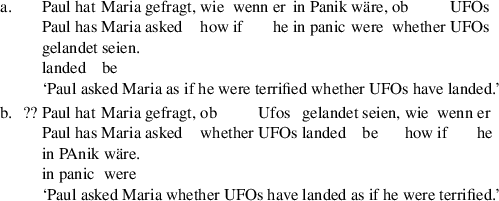

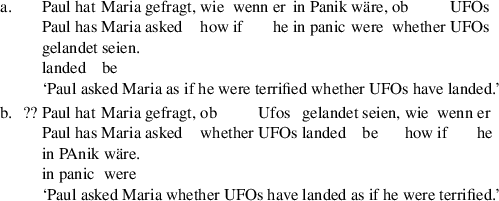

Finally, with both an object clause and a V-HCC in the postfield, the linearization ‘V-HCC > object’ is preferred over ‘object > V-HCC’; see (81a) as opposed to (81b). (Again, the integrated manner interpretation of the V-HCC must be assumed; as a S-HCC, (81b) would be fine.) The linearization preference is also reflected by the fact that event-elaborating indem-clauses—which semantically scope at the level above objects (see Bücking 2014 for their semantics)—must follow V-HCCs; see the contrast in (82). (The contrast emerges only if the subordinate clauses are not read as parentheticals, but rather integrated in just one focus-background structure for the whole complex sentences.)

-

(81)

-

(82)

In sum, the submitted evidence supports the structure in (75), where the compositional integration of the V-HCC precedes the one for objects, subjects, or other higher-level adverbials; see below for the corresponding derivation.

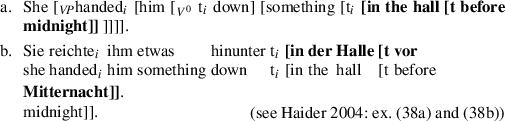

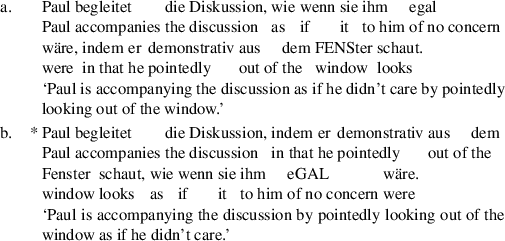

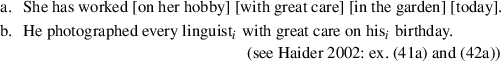

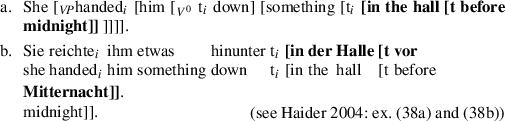

Let me conclude this subsection by relating the given result to the more general question of how to account for (adverbial) adjuncts at the right periphery of a head. The corresponding debates have mainly focused on adverbials that follow the English VP; see, for instance, Pesetsky (1995), Ernst (2002), Frey (2003), Haider (2002, 2004), and Cinque (2004). Further domains touched upon are the postfield in German sentences and adnominal modifiers; see, again, Haider’s work and Bücking (2012). From a descriptive point of view, there is wide agreement on the following rather puzzling pattern: on the one hand, subdomains precede superdomains, suggesting some kind of upward adjunction; on the other hand, binding facts favor an analysis with the right-hand constituents being deeply embedded. The following examples from Haider (2002) serve as an illustration:

-

(83)

In order to solve this major challenge, Haider (2004) argues for treating (certain) right-peripheral adverbials as base-generated extraposed constituents.Footnote 19 The relevant extraposition domain is a strictly right-branching structure licensed by a purely structural head which is not able to identify positions lexically; the guiding intuition here is that a head’s lexical projection, namely its argument structure, is already closed at the right edge. While binding relations are sensitive to the structural embedding, the lack of properly identifying right-peripheral adverbials precludes their usual compositional integration and thereby triggers an incremental interpretation where subdomains must precede superdomains. Example (84) provides an illustration with extraposed elements in bold; the lack of an index on t symbolizes the head’s purely structural role. Notably, for German, the extraposition domain is usually considered readily identifiable because it follows the base position of verbs at the right-hand side (but see below); in (84b), this position is marked by the verbal particle hinunter.

-

(84)

How do V-HCCs fit into this picture? As shown above, they behave as expected: hierarchically, they are embedded; linearly, they immediately follow the verbal head, which is in line with the preferred linearization ‘subdomain > superdomain.’ Crucially, however, since this is as one would hope from an ordinary compositional perspective, V-HCCs do not pose the particular challenge higher-level adverbials are subject to. In terms of Haider’s proposal, V-HCCs should thus not be part of the incrementally interpreted right periphery, but a component of the regular structural integration. Although V-HCCs are projected to the right-hand side of the verb, I conjecture that V-HCCs are not constituents of the extraposed postfield that is sensitive to incremental interpretation. This conjecture can be backed up as follows: for one, if V-HCCs contribute to the verbal complex itself, the notion of a postfield constituent is not applicable to V-HCCs to begin with. Furthermore, non-clausal manner adverbials and other V-related cases such as event-internal locatives (see Maienborn 2001, 2003b and Bücking 2012) are not allowed to the right of the verb; see, for instance, (85):

-

(85)

In fact, according to Haider, this observation substantiates the existence of an incremental domain, and indicates that V-related manner adverbials are not part of it. Then, V-HCCs (which are not discussed by Haider) are an exception that proves the rule: for principled reasons, adverbial sentences cannot be part of the middlefield proper (see, for instance, Reich and Reis 2013); this holds true for V-HCCs as well; see Bücking (2015) and the examples in (86).Footnote 20

-

(86)

Therefore, V-HCCs must follow the verbal head, but they do so as early as possible: they still project within the ordinary structural realm of the verb.Footnote 21

4.2.2 The compositional derivation of the semantic form and its conceptual specification

A structural input as in (75) above, see the sketch in (87), and the meaning components in (88) (where (88c) is the (abbreviated) meaning of the V-HCC motivated in Sect. 4.1) yield, based on MOD* as repeated in (89), the stepwise derivation in (90):

-

(87)

dass [ VP Ben [ V [ V Rad fährt] [ CP wie wenn er betrunken ist]]].

-

(88)

-

(89)

-

(90)

With existentially closing the event argument and substituting it with the more transparent variable e, the (simplified) truth conditions for the full sentence are as follows:

-

(91)

\(\exists e [ \mbox{cycle}'(e) \wedge \mbox{ag}'(e,\mbox{Ben}) \wedge R'(e,v)\wedge \exists E_{hypo} [ R(E_{hypo},V') \wedge \mbox{sim}'(V',v,F)]]\)

This says that there is an event of Ben’s cycling related to some v that is equivalent to those \(V'\) related to hypothetical events \(E_{hypo}\).

This resulting semantic form is underspecified and, thus, amenable to a conceptually plausible specification. According to MOD*, one option is to resolve R and \(R'\) to a manner function. For concreteness, let us assume that both are specified to ‘\(\mbox{manner}_{form}'\)’, that is, a function from events to manners of form; see (92). (I will explain below why both Rs should be specified to the same kind of function.)

-

(92)

\(\exists e [ \mbox{cycle}'(e) \wedge \mbox{ag}'(e,\mbox{Ben}) \wedge \mbox{manner}_{form}'(e,v) \wedge \exists E_{hypo} [ \mbox{manner}_{form}'(E_{hypo},V') \wedge \mbox{sim}'(V',v,F)]]\)

As a result, (92) says that the form manner of Ben’s cycling is equivalent to the form manners of the hypothetical events introduced within the V-HCC; plausible candidates for E hypo are events of Ben’s cycling in situations where he is drunk.

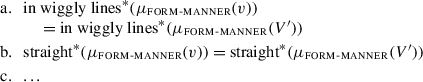

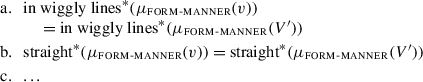

In order to flesh out the relevant notion of ‘sim′’, I transfer the analysis of similarity demonstratives in Umbach and Gust (2014) sketched above to the given adverbial case. Accordingly, the manner function can be said to come along with a generalized measure function as in (93), which maps individuals from the universe of form manners to values of an appropriate conceptual attribute space.

-

(93)

\(\mu_{\text{\textsc{form-manner}}}: U_{\text{\textsc{form-manner}}}\rightarrow \nu \in \{ \text{\textsc{in wiggly lines}}, \text{\textsc{straight}}, \dots\}\)

Notably, since the input in (92) renders the relevant form manners dependent on Ben’s cycling (compare the relation between e and v), the set of potential manners and attribute values is severely constrained, namely, candidates must be compatible with being predicated of cycling events. Moreover, it seems to be obvious that the target domain of form manners is based on a nominal scale, that is, corresponds to a set of unordered elements.

With nominal scales, every value in an attribute space F can be associated with a corresponding basic classifying function p*; for the case at hand, this gives us the set of classifying functions \(C(F_{\textsc{form-manner}})\) in (94). Given the definition for similarity proposed in Umbach and Gust (2014: ex. (37)), and repeated in (95), the form manners v and \(V'\) in (92) are then similar iff the equivalence relations in (96) hold.

-

(94)

\(C(F_{\text{\textsc{form-manner}}}) = \{\mbox{in wiggly lines}^{*}, \mbox{straight}^{*}, \dots\}\)

-

(95)

\(\mbox{sim}'(x,y,F)\ \mbox{iff}\ \forall p^{*} \in C(F): p^{*}(\mu_{F}(x)) = p^{*}(\mu_{F}(y))\)

-

(96)

In other words, the manner of the cycling e, that is v, and the manners of the hypothetical events \(E_{hypo}\), that is \(V'\), are equivalent in the sense that, regarding their form, they yield uniform mappings: they are either all mapped to in wiggly lines or all not mapped to in wiggly lines; they are either all mapped to straight or all not mapped to straight; etc. The same kind of reasoning could be used, for instance, for speed manners and their corresponding measure function \(\mu_{\text{\textsc{speed-manner}}}\).

The given analysis has the following three merits. First, the manner of the explicit matrix event is not said to be referentially identical to those of the embedded hypothetical events; all manners are merely equivalent with regard to their conceptually determined properties. This is as desired, given the ontological facts discussed in Sect. 2.1.

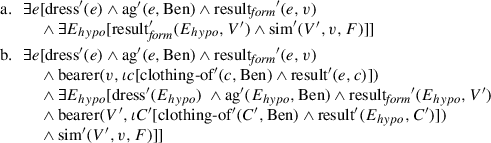

Second, the analysis does not grammatically determine that V-HCCs receive a manner interpretation. According to MOD*, R and \(R'\) can also be instantiated by alternative functions for internal properties such as circumstance′ or result′. This is exactly the case with predicative readings. For instance, with R and \(R'\) as result form ′, (97) receives the conceptual structure in (98a); if the hypothetical events are specified as dressing events and Ben’s resulting clothing is specified as the most plausible bearer of each resulting particularized property, (98a) can be refined to (98b).

-

(97)

-

(98)

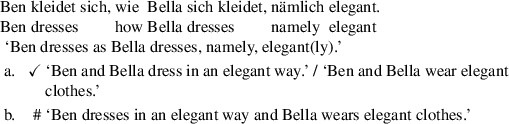

Accordingly, the form of Ben’s clothing, as it results from his actual dressing, is said to be equivalent in some relevant way to the forms of Ben’s clothing, as they result from the hypothetical events. A measure function for clothing forms would map both actual form and hypothetical forms to the same value, for instance, elegant. Note as well that ordinary free relative clauses work analogously; compare (99a) with the conceptual structure in (99b). Such free relatives are straightforward because the embedded event is explicitly given.

-

(99)

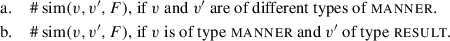

Despite the considerable freedom in determining the relevant entities for comparison, the analysis of V-HCCs and their free relative cognates does not render the instantiation random. The proposed equivalence relation presupposes that the entities said to be equivalent belong to the same supersort; this rules out equivalence between different types of manners and also between manners and results, as is stated in the presupposition failures in (100).

-

(100)

Recall that for specifying the interpretation of (91) to the manner reading in (92) above, both R and \(R'\) were specified to a function for manners of form. The presupposition failure in (100a) now explains on principled grounds why the relation variable at the matrix level and the one related to the hypothetical events must be specified to the same kind of manner function. Moreover, the failure in (100b) smoothly explains why one cannot cross predicative and manner readings; see (101) (= (17) above).

-

(101)

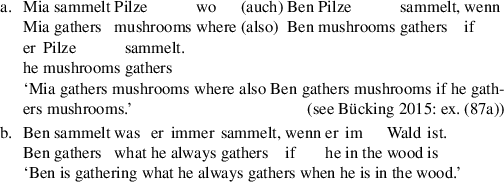

However, the presuppositions do not rule out that manners are equivalent across different types of events as long as they are of the same kind. With regard to free relatives, (102) exemplifies this situation for speed manners: in (102a), the participants of the riding events vary; in (102b), even the basic verbal event descriptions are distinct. V-HCCs behave analogously; recall (103) (= (19) above): here, \(E_{hypo}\) is not specified along the lines of the matrix event. The licensing factor, again, is that both events, despite their being distinct, can be associated with the same kind of manner description.

-

(102)

-

(103)

Third, the proposed equivalence-based analysis of V-HCCs is compositionally attractive. For one, the regular integration of the inner conditional as discussed in Sect. 4.1 is not disturbed in any way; in fact, the given explicit antecedent and its modalized integration forms a crucial factor in determining the relevant entities of comparison and the particular attribute values to be assigned. For (87), world knowledge tells us that drunkenness may impair the form of driving or cycling; most plausibly, then, the speaker intends to say that Ben is cycling in wiggly lines, perhaps even suggesting (under an epistemic reading) that the reason for this is that he is in fact drunk. Moreover, the compositional integration of V-HCCs via MOD* as explicated in (89) makes—without any additional machinery— the correct prediction that the equivalence relation does not hold between events directly, but between event-internal particularized properties. In turn, the behavior of V-HCCs and free relatives lends support to analyses of manner adverbials in terms of separate ontological entities; see Piñón (2008) and Schäfer (2013). In particular, it is not easily reconcilable with a perspective where V-adjacent adverbials merely contribute to event kinds; see the discussion in Anderson and Morzycki (2015) and Maienborn et al. (2016). Most notably, the data in (102) and (103) show that V-HCCs and free relatives may involve fully different event descriptions.Footnote 22

In the next section, I will discuss how the proposal may be systematically adapted to the sentential counterpart of V-HCCs; this provides one further indirect argument in favor of the given approach.

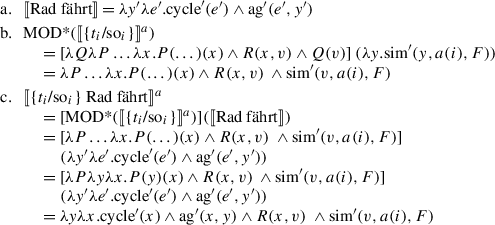

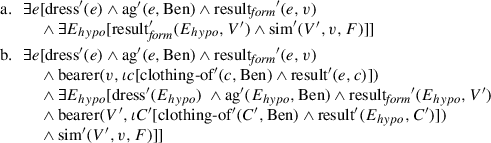

5 Analysis: S-HCCs with wie

The systematic derivation of the meaning of S-HCCs is based on the following core idea: while the basic ingredients—namely equivalence introduced via wie and modalization introduced via an explicit antecedent—are considered fully analogous to those of V-HCCs, S-HCCs involve, both internally and externally, different compositional anchors. These anchors are responsible for the observation made in Sect. 3 that S-HCCs do not compare event-internal properties, but rather the broader situations events are parts of.

Let us first sketch a plausible internal structure for S-HCCs such as (104a) (see (32) above). I propose (104b).

-

(104)

The crucial aspect of (104b) is that wie is not moved from a position that is adjacent to the verbal head of the silent matrix clause, as is the case within V-HCCs; recall (45b) from Sect. 4.1.1. This rules out relating wie to event-internal properties; by contrast, I suggest that wie is moved from a position of the silent consequent that allows access to the topic situation against which the silent consequent as a whole is evaluated (see, amongst others, Maienborn 2003a and Kratzer 2010 for details on topic situations). As far as I see, it is very difficult to argue (on empirical grounds) for one of several possible implementations of this idea; for concreteness, I here assume that wie’s trace is left-adjoined to a silent AspP (see Maienborn 2003a: 160f for compositionally linking topic situations to aspect and Frey 2003, 2004 and Bücking 2012 for further discussion).

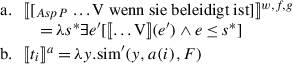

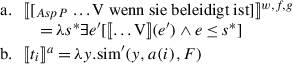

The composition is now straightforward: the internal silent AspP denotes a set of topic situations, as in (105a); I mark topic situations by ∗. Analogously to the implicit events within V-HCCs, their content is not explicitly given. (The conditional antecedent is not interpreted here, as it relates to the silent operator \(\textsc{op}_{\forall}\).) In its base position, wie contributes the familiar equivalence relation, as repeated in (105b). The application of MOD* yields (106), while the subsequent inclusion of the antecedent via the silent operator yields (107).

-

(105)

-

(106)

\([\!\![[_{AspP}\ \mathrm{t}_{i}\ [_{AspP} \dots V\ \mbox{wenn sie beleidigt ist}]] ]\!\!]^{w,f,g,a}\)

\(\quad {}= [\mbox{MOD*} ([\!\![t_{i}]\!\!]^{a})] ([\!\![[_{AspP} \dots V\ \text{wenn sie beleidigt ist}]]\!\!]^{w,f,g}) = \lambda s^{*} \exists e' [[\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e') \wedge e \leq s^{*} \wedge R(s^{*},v) \wedge \mbox{sim}'(v, a(i),F)]\)

-

(107)

\([\!\![[\mbox{\textsc{op}}_{\forall} \dots [_{AspP} \mathrm{t}_{i} [_{AspP} \dots V\ \text{wenn sie beleidigt ist}]]] ]\!\!]^{w,f,g,a} =1\ \text{iff}\ \forall w' [ w' \in Best_{g(w)} (\bigcap(f(w) \cup~\{\{w'': \exists e'' [ e'' \leq w'' \wedge \mbox{offended}'(e'', \mbox{Bella})]\}\})); \forall e [ e \leq w' \wedge \mbox{offended}'(e, \mbox{Bella}); \exists s^{*} \exists e' [ e \leq s^{*} \wedge e' \leq s^{*} \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e') \wedge R(s^{*},v) \wedge \mbox{sim}'(v,a(i),F)]]]\)

Finally, λ-abstraction as triggered by the moved binding relative pronoun renders the assignment-dependent entity λ-bound. This gives us (108) for the whole S-HCC. We will abbreviate this interim result to (109). (The capital letters again symbolize that there are (infinitely) many \(s^{*}_{hypo}\) and v.)

-

(108)

\([\!\![[_{\mathit{CP}}\ \text{wie}_{i}\ [\text{\textsc{op}}_{\forall} \dots [_{AspP} \mathrm{t}_{i}\ [_{AspP} \dots V\ \text{wenn sie beleidigt ist}]]]]]\!\!]^{w,f,g,a} \lambda x \forall w' [ w' \in Best_{g(w)} (\bigcap(f(w) \cup\{\{w'': \exists e'' [ e'' \leq w'' \wedge \mbox{offended}'(e'', \mbox{Bella})]\}\})); \forall e [ e \leq w' \wedge \mbox{offended}'(e, \mbox{Bella}); \exists s^{*} \exists e' [ e \leq s^{*} \wedge e' \leq s^{*} \wedge [\!\![\dots \mathrm{V} ]\!\!](e') \wedge R(s^{*},v) \wedge \mbox{sim}'(v,x,F)]]]\)

-

(109)

\(\lambda x \exists S^{*}_{hypo} [ R(S^{*}_{hypo}, V) \wedge \mbox{sim}'(V,x, F)]\)

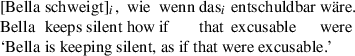

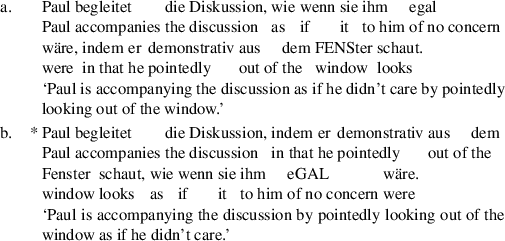

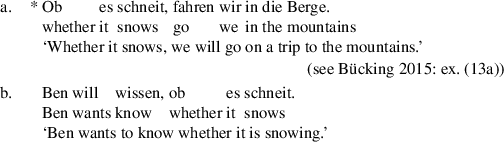

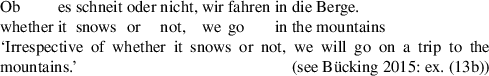

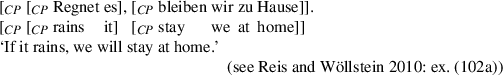

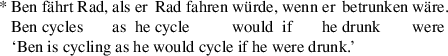

The next step concerns the link between the S-HCC as a whole and its external matrix host. The clear non-integration of S-HCCs (recall the observations made in Sect. 3) suggests a high adjunction site; so, here we do have empirical reasons for adjunction above the VP-level. In keeping with the proposal for different levels of clausal linkage in Reis (1997), I assume that S-HCCs adjoin at the CP-level; see (110).

-

(110)

[ CP [ CP Bella schweigt], [ CP wie wenn sie beleidigt ist]].

Note as well that CP-adjunction is not confined to the right periphery. Reis and Wöllstein (2010) show that verb-first conditionals in German are syntactically unintegrated, even if fronted. In order to capture their non-integration, Reis and Wöllstein argue for their adjunction to the left of the finite verb, as in (111). This position is feasible for S-HCCs as well, as shown by (112) (see Bücking 2015 for details on the topological behavior of HCCs in general).

-

(111)

-

(112)

[ CP [ CP Wie wenn sie beleidigt ist], [ CP schweigt Bella]].

One can safely conclude that S-HCCs modify neither the given matrix event nor any of its internal components; these options would need the VP or the verbal head as their compositional anchors. Instead, I assume that CP-adjunction is compatible with relating the S-HCC to the topic situation of the matrix clause, \(s^{*}\) in the following; this yields—applying MOD* and existential closure of events and situations as usual—the representation in (113).

-

(113)

\([\!\![[_{\mathit{CP}}\ [_{\mathit{CP}}\text{Bella schweigt}],\ [_{\mathit{CP}}\ \text{wie wenn sie beleidigt ist}]]]\!\!] {}=1\ \text{iff}\ \exists s^{*} \exists e \exists S^{*}_{hypo} [R'(s^{*}, v') \wedge e \leq s^{*} \wedge \mbox{keep silent}'(e) \wedge \mbox{ag}'(e,\mbox{Bella}) \wedge R(S^{*}_{hypo}, V) \wedge \mbox{sim}'(V,v', F)]\)

Logical forms for sentences modified by S-HCCs then say that the equivalence relation brought in by wie holds between topic-related entities—the entities V are made available by the hypothetical topic situations of the silent consequent, while \(v'\) relates to the topic situation of the explicit matrix clause.

The given underspecified representation calls for a conceptual enrichment. According to MOD*, R is the identity function if the composition takes place where the conceptual structure of the modifier’s target is no longer available. In the verbal domain, this is the case at the phrasal level; recall from the preceding sections that, thus, VP-modifiers relate to events as wholes while head-related modifiers target their internal structure. According to the structure above, both the internal wie and the S-HCC adjoin to full XPs; that is, one can conjecture that they target the relevant topic situations as wholes as well. So, using identity for both R and \(R'\), (113) can be simplified to (114); accordingly, the topic situations themselves are said to be equivalent to each other.

-

(114)

\(1\ \text{iff}\ \exists s^{*} \exists e \exists S^{*}_{hypo} [ e \leq s^{*} \wedge \mbox{keep silent}'(e) \wedge \mbox{ag}'(e,\mbox{Bella}) \wedge \mbox{sim}'(S^{*}_{hypo},s^{*}, F)]\)

The crucial question now is how equivalence between situations is defined. Or, in other words, in relation to what kind of attribute spaces F can situations be considered as equivalent? I would like to put forward the hypothesis that situations are characterized by their subsituations, including relevant event descriptions. This is captured by the generalized measure function μ situation in (115), which maps situations from the universe of situations onto concepts for subsituations.

-

(115)

\(\mu_{\textsc{situation}}: U_{\text{\textsc{situation}}} \rightarrow \nu \in \{\text{\textsc{contains sit. a}}, \text{\textsc{contains sit. b}}, \dots\}\)