Abstract

This paper argues, based on the interaction of head movement and ellipsis possibilities in Russian, that certain types of head movement must take place in the narrow syntax. It does so by examining a variety of Russian constructions which are unified in several ways: they express some type of polarity focus; they involve head movement of the verbal complex to a high position (Pol), resulting in discourse-marked vso orders; and some of them involve ellipsis (of either vP or TP). Investigation of the interaction of the head movement and ellipsis possibilities of the language yields three of four logically possible patterns. I argue that the unattested pattern should be explained using reasoning that invokes MaxElide (Merchant 2008)—a principle normally used to explain why the larger of two possible ellipsis domains must be chosen if Ā-movement has occurred out of the ellipsis site. Extending this logic to the interaction of head movement and ellipsis requires that we take head movement to be a syntactic phenomenon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

‘And for no and yes, what’s here—Anti-no and anti-yes!’ Published translation by Ainsley Morse and Bela Shayevich, from I live I see/Selected Poems/Vsevolod Nekrasov. 2013.

For rhetorical convenience, I omit examples involving auxiliaries, putting off discussion of those for a separate paper.

See Messick and Thoms (2016) for an important discussion in which Hartman’s (2011) data are re-considered in light of the possibility that MaxElide effects can be subsumed by more general constraints on ellipsis parallelism, which predict that certain MaxElide violations should be possible. Messick and Thoms (2016) demonstrate that these violations are countenanced in English; it would be interesting to consider whether they are also countenanced in the parallel Russian cases—but this is a task that falls beyond the scope of the present paper.

An exception to this general line of thinking is the proposal in Tracy King’s (1995) dissertation, which argues for movement of the verb to T and subsequent movement of the subject to a higher topic position. See also Sect. 3.2 for a discussion of the possibility that the subject may remain in situ in some instances.

This kind of analysis requires reference to upward valuation in agree. This is a controversial move, insomuch as it is associated with theoretical ramifications and empirical predictions that are the subject, currently, of some intensive investigation (see Preminger and Polinsky 2015; Bjorkman and Zeijlstra 2014). The evidence for the use of upward valuation in this particular case seems quite strong, and it is difficult to think of ways in which incorrect predictions would arise for Russian if upward agree were made available. This is, however, a move worthy of further investigation beyond the confines of this paper.

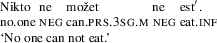

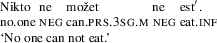

I assume here that predicates like dolžen and možet are raising predicates, although they could also involve restructuring. In either case it is important to note that there are acceptable instances of two negations, one in the higher and one in the lower clauses. If negation appears in the higher clause, the n-word is licensed:

-

(18)

-

(18)

A reviewer has pointed out that the argument loses its force if the example involves a raised (negated) verb, as in (1d). This is because even if Neg carries valued features (contra the current proposal), it will also bear focus and will raise out of the ellipsis site. Focused constituents famously do not count for the purposes of identity conditions on ellipsis; see Merchant (2001). In such a configuration, even if Neg is what bears valued polarity features, it would also bear focus, and would therefore not be subject to the identity condition on ellipsis for independent reasons. The relevance of examples like (21), then, is that it is quite obviously the polarity particle that bears any focus, rather than the sentential negation itself (on either of the approaches entertained here).

A notable exception is Slioussar (2011), where vs orders are discussed as being fairly commonplace. That work does not, however, consider cases of the type discussed here (involving polarity focus).

Many of the examples cited in this and later sections have been culled from the Russian National Corpus, which contains natural language texts drawn from newspapers and various forms of spontaneous speech (interviews, etc.). It is available at http://www.ruscorpora.ru/en/ (Accessed 9 February 2017). The constructions under analysis here are very colloquial and therefore appear primarily in examples representing live speech, either in fictional texts, blogs, or interviews.

Andrej Volos. Nedvižimost′ (2000) // “Novyj Mir”, 2001 (rnc).

Ju. O. Dombrovskij, Xranitel′ drevnostej, čast′ 1, 1964 (rnc).

Vasilij Aksenov. Zvezdnyj bilet. // “Junost′”, 1961 (rnc).

Examples from the corpus (rnc) all contain də, because it was easier to search for such examples. But all the corpus examples listed here would also be felicitous without the particle.

The discourse particle də has numerous functions, some of which are described in Kolesnikova (2014). In the contexts of importance to us, it seems to serve as a marker of contrast and reversal; I leave further discussion of its other meanings for another time.

For notational convenience I take the movement to be from Neg to Pol directly, though locality conditions may dictate that the head also moves through T. I have no evidence bearing on this question, and what follows is consistent with either position.

A reviewer notes that example (29a) seems suboptimal to him/her and also two other native speakers consulted. Unsurprisingly, (s)he also noted that omitting the complementizer leads to improvement. I consulted with several native speakers who found both variants completely acceptable, but nonetheless the variability should be noted here, whatever its source.

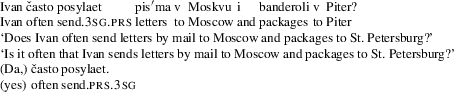

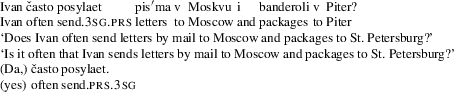

As a reviewer points out, the situation is not as simple when it comes to responses to polar questions, discussed in more detail in Sect. 4.2:

-

(34)

The response in (34) is more acceptable than the examples in (35), where the adverb is also placed before the verb in vso configurations. The discourse function of utterances like (35) is also distinct from that of plain polar questions, in a way that may help us understand the contrast between (34) and (35). A plain polar question involves focus on the polarity, either via word order—fronting of the verb and the appearance of a second position polar question particle, li—or via intonation (a rise on the verb in its canonical position). There are also ways of focusing constituents in polar questions, yielding a cleft-like interpretation; this is in fact the likeliest interpretation of the question in (35). The response, therefore, is likely to involve a focusing on the adverb and therefore also fronting of that adverb to above the Pol position.

-

(34)

For the purposes of clarity in the discussion that follows, I ignore the type of ellipsis that strands an auxiliary, eliding a complement that is probably the size of AspP.

The verbal version of the response in (39) is permitted, but this instantiates a different strategy, namely vvpe with subject drop—see examples (61) and (62) in Sect. 5.

The obligatory absence of the pre-verbal argument in certain verb-stranding constructions was noted by Bailyn (2014), who argued that this constituted evidence against the vvpe approach to verb-stranding constructions, in which there is verb movement to Asp/Neg and ellipsis of vP (Gribanova 2013b). Without getting into detail, Gribanova (2013a) pointed out that there may be other sources for this pattern. The current paper provides an explanation for this observation, which is that there are two head movement possibilities and (at least) two sizes of ellipsis domain; one of these possibilities (TP ellipsis) will elide the subject along with other TP-internal material. Since this particular strategy is employed under discourse conditions that involve polarity focus, we expect the pre-verbal subject to be banned just under those discourse conditions, but permitted in cases where polarity focus is absent. See the examples in Sect. 5.1 for evidence in favor of this perspective.

This idea is pre-figured in Kazenin (2006), where it is hypothesized that auxiliaries may also move to Σ under the right discourse conditions, leading to their ability to participate in the contrastive polarity ellipsis construction. The idea is not extended to lexical verbs, but the move seems a natural one in this context.

Full vso answers to questions, as presented in (51), are less preferred in the default case, ellipsis being a much more felicitous option. A full, unelided answer communicates more emphasis and is more compatible with a context in which the responder in the discourse is aggravated with the question, for example.

Recall that the unelided vso response to the question in (60), shown in (51), is acceptable.

Asserting that there is no polarity focus in such examples is a tricky business, because stranding of an element outside an ellipsis site commonly involves some kind of focus, be it polarity focus or otherwise. Suffice it to say that in the examples in (61,62), the stranded verb is not addressing the matrix alternatives p or ¬p. In (61), these matrix alternatives amount to {they asked Anya to…, they did not ask Anya to…}; in (62), they amount to {it worked out, it did not work out}.

Andrej Volos. Nedvižimost′ (2000) // “Novyj Mir”, 2001 (rnc).

Some subset of speakers considers these degraded, but stop short of describing them as ungrammatical. This is true primarily in the cases with negation in the response—a fact for which I have no explanation at this stage.

Thanks to Sandra Chung, p.c., for asking the question that led to this reasoning.

This holds as long as we also assume Heim’s (1997) ban on meaningless co-indexation, which makes sure that the free variable in the antecedent and elided constituent are not accidentally co-indexed.

Following Hartman (2011), I assume that covert quantifier raising will take place in the antecedent constituent, creating a structure parallel to the paralellism domain. See below for discussion of the extension of this assumption, along with the rest of the MaxElide logic, to head movement.

A reviewer notes that we may expect independent evidence of covert verb movement in polar questions with an in situ verb. These effects, if they exist, will be very subtle and difficult to illustrate. This is because the primary source of such evidence comes from scope judgments involving modals and quantifiers in monoclausal structures (see, for example, Lechner 2007). Russian modals dolžen ‘ought’ and možet ‘may’ are either raising or restructuring predicates and therefore involve bi-clausal structures, making scope judgments more difficult. Even if those judgments were clear, given the bi-clausal nature of these structures, it would take independent analysis to understand what the predictions would even be in such cases. If independent evidence for covert verb movement exists in this language, the relevant effects will likely look quite different in Russian. For this reason, I leave this very interesting question open for future research. Finally, it is worth noting that LF movement of the verb to a high position is an essential component of Abels’ (2005) account, since this is what leads to the inability of so-called ‘expletive’ negation to license n-words, even when the negation appears in situ in the narrow syntax.

Though see Messick and Thoms (2016) for discussion of the possibility that A-movement may not be relevant for MaxElide, at least in certain cases.

References

Abels, Klaus. 2005. “Expletive” negation in Russian: A conspiracy theory. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 1(13): 5–74.

Babko-Malaya, Olga. 2003. Perfectivity and prefixation in Russian. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 11(1): 5–36.

Babyonyshev, Maria. 1996. Structural connections in syntax and processing: Studies in Russian and Japanese grammatical subject in first language acquisition. PhD diss., MIT.

Bailyn, John Frederick. 1995a. A configurational approach to Russian ‘free’ word order. PhD diss., Cornell University.

Bailyn, John Frederick. 1995b. Underlying phrase structure and ‘short’ verb movement in Russian. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 3(1): 13–58.

Bailyn, John Frederick. 2004. Generalized inversion. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 22: 1–49.

Bailyn, John Frederick. 2012. The syntax of Russian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bailyn, John Frederick. 2014. Against a VP ellipsis account of Russian verb-stranding constructions. In Studies in Japanese and Korean linguistics and beyond, ed. Alexander Vovin. Leiden: Brill.

Bjorkman, Bronwyn, and Hedde Zeijlstra. 2014. Upward Agree is superior. Ms. University of Toronto and Georg-August-Universität Göttingen.

Boeckx, Cedric, and Sandra Stjepanović. 2001. Heading towards PF. Linguistic Inquiry 2(32): 345–355.

Brown, Sue. 1999. The syntax of negation in Russian. Stanford: CSLI.

Brown, Sue, and Steven Franks. 1995. Asymmetries in the scope of Russian negation. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 2(3): 239–287.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 8–153. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chung, Sandra. 2006. Sluicing and the lexicon: The point of no return. In Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (BLS) 31, eds. Rebecca T. Cover and Yuni Kim, 73–91. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Chung, Sandra. 2013. Syntactic identity in sluicing: How much and why. Linguistic Inquiry 44(1): 1–44.

Chung, Sandra, Bill Ladusaw, and James McCloskey. 1995. Sluicing and logical form. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 3(3): 239–282.

Comrie, Bernard. 1973. Clause structure and movement constraints in Russian. In 9th Regional Meeting, Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS), 291–304. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Erteschik-Shir, Nomi, Lena Ibnbari, and Sharon Taube. 2013. Missing objects as Topic Drop. Lingua 136: 145–169.

Farkas, Donka. 2010. The grammar of polarity particles in Romanian. In Edges, heads, and projections: Interface properties, eds. Anna Maria Di Sciullo and Virginia Hill, 87–124. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Farkas, Donka, and Kim Bruce. 2010. On reacting to assertions and polar questions. Journal of Semantics 27: 81–118.

Farkas, Donka, and Floris Roelofsen. 2015. Polarity particle responses as a window onto the interpretation of questions and answers. Language 2(91): 359–414.

Fiengo, Robert, and Robert May. 1994. Indices and identity. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Fowler, George. 1994. Verbal prefixes as functional heads. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 24(1–2): 171–185.

Georgi, Doreen, and Gereon Müller. 2010. Noun-phrase structure by Re-Projection. Syntax 13(1): 1–36.

Goldberg, Lotus. 2005a. On the verbal identity requirement in VP ellipsis. Presented at the Identity in Ellipsis workshop, UC Berkeley.

Goldberg, Lotus. 2005b. Verb-stranding vp ellipsis: A cross-linguistic study. PhD diss., McGill University.

Grebenyova, Lydia. 2006. Sluicing puzzles in Russian. In Annual Workshop on Formal Approaches to Slavic lInguistics (FASL)14, eds. James Lavine, Steven Franks, Mila Tasseva-Kurktchieva, and Hana Filip, 157–171. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Grebenyova, Lydia. 2007. Sluicing in Slavic. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 15(1): 49–80.

Gribanova, Vera. 2013a. A new argument for verb-stranding verb phrase ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 44(1): 145–157.

Gribanova, Vera. 2013b. Verb-stranding verb phrase ellipsis and the structure of the Russian verbal complex. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31(1): 91–136.

Hall, David. 2015. Spelling out the noun phrase: Interpretation, word order, and the problem of ‘meaningless movement’. PhD diss., Queen Mary University of London.

Harizanov, Boris. 2014a. Clitic doubling at the syntax-morphophonology interface: A-movement and morphological merger in Bulgarian. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 4(32): 1033–1088.

Harizanov, Boris. 2014b. On the mapping from syntax to morphophonology. PhD diss., University of California, Santa Cruz.

Harley, Heidi. 2004. Merge, conflation, and head movement. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 34, eds. Keir Moulton and Matthew Wolf, 239–254. Amherst: GLSA.

Hartman, Jeremy. 2011. The semantic uniformity of traces: Evidence from ellipsis parallelism. Linguistic Inquiry 42(3): 367–388.

Harves, Stephanie. 2002. Genitive of negation and the syntax of scope. In ConSOLE 10, eds. Marjo van Koppen, Erica Thrift, Erik Jan van der Torre, and Malte Zimmerman, 96–110.

Heim, Irene. 1997. Predicates or formulas? Evidence from ellipsis. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 7, ed. Aaron Lawson, 197–221. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Holmberg, Anders. 2001. The syntax of yes and no in Finnish. Studia Linguistica 55(2): 140–174.

Holmberg, Anders. 2013. The syntax of answers to polar questions in English and Swedish. Lingua 128: 31–50.

Jones, Bob Morris. 1999. The Welsh answering system. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kallestinova, Elena. 2007. Aspects of word order in Russian. PhD diss., University of Iowa.

Kazenin, Konstantin. 2006. Polarity in Russian and Typology of Predicate Ellipsis. Ms. Moscow State University.

King, Tracy Holloway. 1995. Configuring topic and focus in Russian. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Kolesnikova, Svetlana. 2014. Russkie časticy. Semantika, grammatica, funkcii. Moscow: Flinta.

Koopman, Hilda, and Anna Szabolcsi. 2000. Verbal complexes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kramer, Ruth, and Kyle Rawlins. 2011. Polarity particles: An ellipsis account. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 39, eds. Suzi Lima, Kevin Mullin, and Brian Smith. Amherst: GLSA.

Krifka, Manfred. 2011. How to interpret “expletive” negation under bevor in German. In Language and logos. Studies in theoretical and computational linguistics, eds. Thomas Hanneforth and Gisbert Fanselow, 214–236. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Laka, Itziar. 1990. Negation in syntax: On the nature of functional categories and projections. PhD diss., MIT.

Laleko, Oksana. 2010. Negative-contrastive ellipsis in Russian: Syntax meets information structure. In Formal Studies in Slavic Linguistics, eds. Anastasia Smirnova, Vedrana Mihaliček, and Lauren Ressue, 197–218. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Lambova, Mariana. 2004. On triggers of movement and effects at the interfaces. In Studies in generative grammar, 75: Triggers, eds. Anne Breibarth and Henk C. van Reimsdijk, 231–258. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Landau, Idan. 2006. Chain resolution in Hebrew (V)P-fronting. Syntax 9(1): 32–66.

Langacker, Ronald. 1966. On pronominalization and the chain of command. In Modern studies in English, eds. David A. Reibel and Sanford A. Schane, 160–186. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Lasnik, Howard. 2001. When can you save a structure by destroying it? In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 31, eds. Min-Joo Kim and Uri Strauss, 301–320. Amherst: GLSA.

Lechner, Winifred. 2007. Interpretive effects of head movement. http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/000178. Accessed 9 February 2017.

Lipták, Anikó. 2012. V-stranding ellipsis and

verbalidentity: The role of polarity focus. In Linguistics in the Netherlands 2012, eds. Marion Elenbaas and Suzanne Aalberse, 82–96. Amsterdam: Benjamins.Lipták, Anikó. 2013. The syntax of emphatic positive polarity in Hungarian: Evidence from ellipsis. Lingua 128: 72–92.

Matushansky, Ora. 2006. Head movement in linguistic theory. Linguistic Inquiry 1: 69–109.

McCloskey, James. 2011. The shape of Irish clauses. In Formal approaches to Celtic linguistics, ed. Andrew Carnie, 143–178. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

McCloskey, James. 2012. Polarity, ellipsis and the limits of identity in Irish. Workshop on Ellipsis, Nanzan University. https://people.ucsc.edu/~mcclosk/PDF/nanzan-handout.pdf. Accessed 9 February 2017.

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands and the theory of ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 2006. Why no(t)? Style 20(1–2): 20–23.

Merchant, Jason. 2008. Variable island repair under ellipsis. In Topics in ellipsis, ed. Kyle Johnson, 132–153. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Merchant, Jason. To appear. Ellipsis: A survey of analytical approaches. In The Oxford handbook of ellipsis (to appear), eds. Jeroen Van Craenenbroeck and Tanja Temmerman. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 2013a. Polarity items under ellipsis. In Diagnosing syntax, eds. Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng and Norbert Corver, 441–462. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 2013b. Voice and ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 44(1): 77–108.

Messick, Troy, and Gary Thoms. 2016. Ellipsis, economy and the (non)uniformity of traces. Linguistic Inquiry 47(2): 306–332.

Milićević, Nataša. 2006. On negation in yes/no questions in Serbo-Croatian. In UiL OTS working papers 2006, eds. Jakub Dotlacil and Berit Gehrke, 29–47.

Ngonyani, Deo. 1996. VP ellipsis in Ndendeule and Swahili applicatives. In Syntax at Sunset, UCLA working papers in syntax and semantics 1, eds. Edward Garrett and Felicia Lee, 109–128. Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Linguistics.

Pesetsky, David. 1982. Paths and categories. PhD diss., MIT.

Piñón, Christopher. 1991. Presupposition and the syntax of negation in Hungarian. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 27. Part two: The parasession on negation, eds. Lise M. Dobrin, Lynn Nichols, and Rosa M. Rodriguez, 246–262.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1989. Verb movement, universal grammar, and the structure of IP. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 365–424.

Pope, Emily. 1976. Questions and answers in English. PhD diss., MIT.

Preminger, Omer, and Maria Polinsky. 2015. Agreement and semantic concord: A spurious unification. Ms., University of Maryland.

Progovac, Ljiljana. 1994. Negative and positive polarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Progovac, Ljiljana. 2005. Negative and positive feature checking and the distribution of polarity items. In Negation in Slavic, eds. Sue Brown and Adam Przepiórkowski, 179–217. Bloomington: Slavica Publishers.

Roberts, Ian. 2010. Agreement and head movement: Clitics, incorporation, and defective goals. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. Ellipsis redundancy and reduction redundancy. In Stuttgart Ellipsis Workshop, eds. Steve Berman and Arild Hestvik. Stuttgart: Universität Stuttgart.

Sadock, Jerold, and Arnold Zwicky. 1985. Speech act distinctions in syntax. In Language typology and syntactic description. Vol. 1. Clause structure, ed. Timothy Shopen, 155–196. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Santos, Ana Lúcia. 2009. Minimal answers. Ellipsis, syntax and discourse in the acquisition of European Portuguese. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Schachter, Paul. 1977. Does she or doesn’t she? Linguistic Inquiry 8: 763–767.

Schoorlemmer, Erik, and Tanja Temmerman. 2012. Head movement as a PF-phenomenon: Evidence from identity under ellipsis. In 29th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL), eds. Jaehoon Choi, E. Alan Hogue, Jeffrey Punske, Deniz Tat, Jessamyn Schertz, and Alex Trueman, 232–240. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Sekerina, Irina. 1997. The syntax and processing of split scrambling constructions in Russian. PhD diss., CUNY Graduate School.

Slioussar, Natalia. 2011. Russian and the EPP requirement in the tense domain. Lingua 121(14): 2048–2068.

Svenonius, Peter. 2004. Slavic prefixes inside and outside VP. Nordlyd 32(2): 205–253.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 2011. Certain verbs are syntactically explicit quantifiers. In The Baltic international yearbook of cognition, logic and communication. Vol. 6, formal semantics and pragmatics: Discourse, context, and models. http://cognition.lu.lv/symp/6-call.html. Accessed 9 February 2017.

Takahashi, Shoichi, and Danny Fox. 2005. MaxElide and the re-binding problem. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 15, eds. Effi Georgala and Jonathan Howell, 223–240. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Tovena, L. M. 1995. An expletive negation which is not so redundant. In Grammatical theory and Romance languages: Selected papers from the 25th linguistic symposium on Romance languages, ed. Karen Zagona, 263–274. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Van Gelderen, Véronique. 2003. Scrambling unscrambled. Utrecht: LOT Publications.

Vicente, Luis. 2009. An alternative to remnant movement for partial predicate fronting. Syntax 12(2): 158–191.

Zanuttini, Raffaella. 1997. Negation and clause structure: A comparative study of Romance languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

For generous feedback and discussion on aspects of this project, I thank Jonathan Bobaljik, Sandy Chung, Cleo Condoravdi, Amy Rose Deal, Donka Farkas, Julie Goncharov, Boris Harizanov, Beth Levin, Jason Merchant, Jim McCloskey, Luis Vicente, and audiences at NELS 45, University of Maryland, University of Connecticut, and UCSC. Special thanks are due to Chris Potts and Daria Popova, who worked with me in the early stages of thinking through a number of the puzzles presented here. I’m grateful to three anonymous reviewers who provided extensive and very helpful comments. Thanks to Dina Brun, Alla Oks, Julia Kleyman, Anya Desnitskaya, Asya Pereltsvaig, Ekaterina Kravtchenko, Asya Shteyn, Maria Borshova, Allen Gessen, David Erschler, Natasha Sergeeva, Alla Zeide, Flora and Anatoly Tomashevsky, and Irina and Alexander Gribanov for providing judgments and discussing the data with me. I am grateful to the Stanford Humanities Center for financial and practical support. Errors are the author’s responsibility alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gribanova, V. Head movement and ellipsis in the expression of Russian polarity focus. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 35, 1079–1121 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9361-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9361-4