Abstract

In this paper, I argue that the traditional analysis of null arguments—subjects and objects—in American Sign Language needs to be re-evaluated. It is typically assumed that in the absence of agreement, the null argument is either a topic-bound variable or a silent pronoun (pro). I introduce novel data that pose a problem for both of these views. As the null argument is subjected to a variety of diagnostics, I demonstrate that it is best analyzed as a case of ellipsis of a non-branching argument of the verb—a bare NP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The nature of this classification lies outside of the scope of this paper. For the purposes of this paper, I will continue using the traditional (agreeing vs. plain) terminology but adopt the following convention: when the verb is modified accordingly, a small-case letter, corresponding to the locus of the referent, is added to the verb itself but separated from it with a hyphen. In this, thus identified loci are noted separately from the semantic indices of referential expressions, which, by common convention, are in subscript italics.

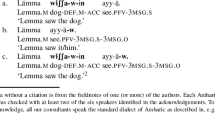

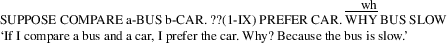

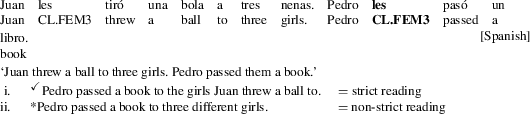

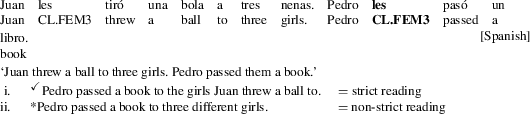

By convention, ASL lexical items are glossed in all caps. In cases reported as ‘A:’ and ‘B:’, both A and B are engaged in a dialog. Often these items correspond directly to the English translations (e.g. LOVE–‘love’) but that is not always the case (e.g. PAH–‘finally’); therefore, translation is provided. Finger-spelling is indicated by dashes between capital letters: e.g. J-E-F-F. Names that have not been finger-spelled are name signs (signs typically created specifically for and identified with particular individuals); if a name sign is not marked for locus, it is produced on the body of a signer. A handshape involving pointing to a particular area of space (is often, though not always, assumed to be a pronoun) is glossed as IX. The location of the sign in space (locus) is shown in small letters, connected to the lexical item by a dash: a-SELF; the interpretational index is given in subscript in italics: SELF i . This approach is somewhat non-traditional in Sign Linguistics; it is adopted here because both the presence/absence of locus and interpretational possibilities of the element are relevant for the discussion.

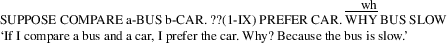

Non-manual markers (particular facial expressions associated with particular grammatical constructions) are indicated by a line above the lexical item(s) involved ending with the abbreviation for the type of construction, e.g. t for topicalization and wh/ y/n for an interrogative:

-

(i)

t

MARY…

‘As for Mary…’

-

(ii)

y/n

2-IX KNOW JEFF

‘Do you know Jeff?’

-

(i)

Lillo-Martin (1991) discusses this phenomenon in terms of Strong Crossover.

Lillo-Martin argues that embedded clauses are islands in ASL.

I remain agnostic regarding the nature of the Ø in Mandarin Chinese. For an extensive discussion of various analyses, see Chen (2012).

Bahan et al. adopt Bahan’s (1996) account of non-manuals: head-tilt as instantiating subject- and eye-gaze as instantiating object agreement in ASL. However, subsequent experimental studies (cf. Thompson et al. 2006) have questioned the view of these non-manuals as markers of morphological agreement.

We take the area immediately in front of a signer to be a neutral location (Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006).

It is also possible to establish this locus by introducing a point (a-IX) earlier in the utterance.

Languages with this property differ with respect to whether overt referents are allowed. For instance, Spanish permits the use of an overt argument in cases like (16) (certain restrictions apply, see Barbosa 2009 for an overview), while Modern Irish does not (cf. McCloskey and Hale 1984). In particular, McCloskey and Hale argue that in Irish, the ‘agreement morpheme’ serves as the ‘(inflectional) argument’: for the sentence to be grammatical, either the referent must be overt and the morpheme absent, or vice versa.

An alternative view is that there is no pro (in the relevant syntactic position), and Agr itself is pronominal (cf. Borer 1989; Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1998; Barbosa 2009, i.a.). On this approach (i.e. pro does not exist, and the burden of the θ-role carrier must be placed on Agr), Agr itself is referential, and interpretations of the null argument that are other than definite (e.g. specific indefinite) remain unexpected.

Such ambiguity is atypical of Sign Language discourse but may arise in special circumstances where spatial disambiguation is problematic/impossible. One such circumstance is ‘whispering’—signing below and to the side of the typical signing plane and with much reduced space—the identity of the referent is impossible to identify through the eye-gaze and head-tilt. Yet, the sentences are grammatical.

By convention, Deaf (vs. deaf) refers to the cultural identification (including language) of a deaf individual, rather than to the hearing status; Coda is a term that always refers to hearing children of deaf adults, who may or may not exhibit native proficiency in both of their languages (not unlike other bilinguals). Two of the Deaf consultants have assisted in linguistic research for over 15 years. All Codas consulted are native signers, currently employed as interpreters. All but two consultants were white, raised in the Northeastern part of the US (New York, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut).

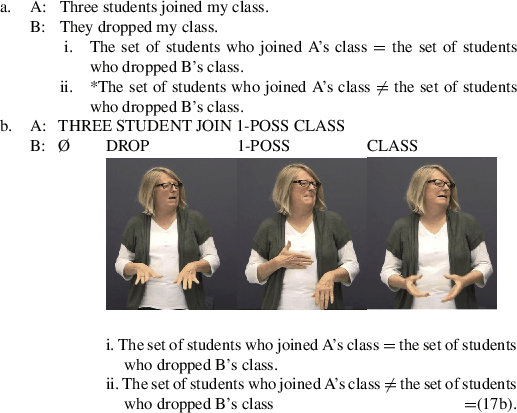

Note that the anaphoricity of the null argument is exploited in Lillo-Martin (1991): the analysis of Ø as being bound by a topic upstairs allows for or even implies anaphoricity. On a related note, an anonymous reviewer questions whether this anaphoricity can be teased apart from the anaphoricity in the establishment of the spatial loci. The relation between anaphoricity and loci is independently complex and is briefly discussed in Sect. 5. The key data offered in this paper demonstrate that at the heart of the generalization is something other than ‘locus matching’: e.g., the NP KID in (i)–(ii) is a body-anchored sign (no locus is introduced); yet, unless the anaphoricity requirement is met, (i)–(ii) below are ungrammatical. Otherwise, the range of readings remains available.

-

(i)

a.

A:

PETER LIKE a-POSS KID

b.

A:

WHAT’S-UP ≈(17)

‘Peter likes his kid.’

‘What’s up?’

B:

JEFF HATE Ø

B:

*JEFF HATE Ø

‘Jeff hates ___.’

‘Jeff hates ___.’

-

(ii)

a.

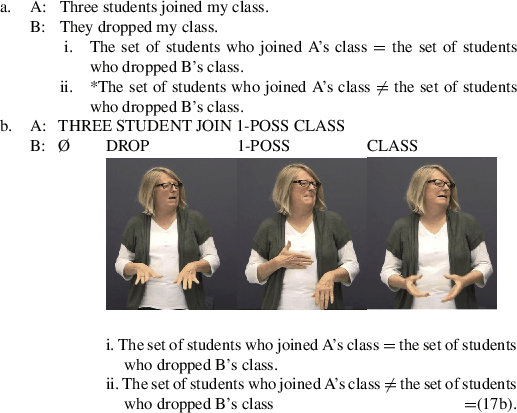

A:

THREE KID JOIN 1-POSS CLASS

b.

A:

WHAT’S-UP

‘Three kids joined my class.’

‘What’s up?’

B:

Ø DROP 1-POSS CLASS

B:

*Ø DROP 1-POSS CLASS

‘___ dropped my class.’

‘___ dropped my class.’

The data also speak to a particular version of ellipsis—that the elided element is something ‘semantically empty,’ like ONE (Elbourne 2005) or simply an indefinite pronoun (Hoji 1998). If this were the case, (i.b) (with an appropriate context) and (ii.b) would have been grammatical, yielding something like Jeff hates somebody and Someone dropped my class, contrary to the facts.

-

(i)

(18)–(19) record a limited set of verbs and serve as a representative sample; however, this pattern is fully productive. A number of verbs have been examined (see Koulidobrova 2012a): LOVE, HATE, ANSWER, KISS, SEND, BUY, FORGET, REMEMBER, SKIP, JOIN, WORRY, REJECT. The pattern remains the same. Additionally, ASL has been argued to differentiate between 1st vs. non-1st person pronouns (Meier 1990). The nature of the 1st person referring elements lies outside the scope of this paper. Empirically, the generalization (which does not extend to the non-1st person) is as follows: a 1st person subject can be omitted if it is not obviously anaphoric but can be inferred—e.g. (18B.c.) on the 1-IX reading (for a possible account, see Meir et al. 2007). But this generalization does not always hold either: my consultants report the necessity of 1-IX in (i) (discussed in the main text as (71c)), where, in the absence of 1-IX, the referent is inferable, yet the sentence is dispreferred:

-

(i)

-

(i)

Note that I am not suggesting that there are no implicit arguments in ASL; rather that it is not the case that all instances of Ø can be analyzed as such.

In addition, Malamud (2012, i.a.) argues that semantically, arbs are definite plurals—they lack the quantificational variability effects (QVE) that arise with indefinites. Thus, the fact that Ø in ASL allows for a reading other than definite further argues against the ‘arb’-style account.

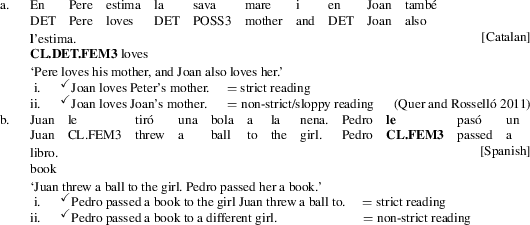

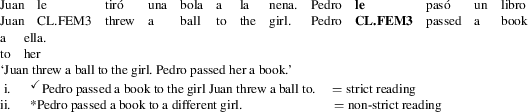

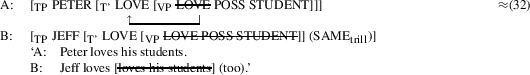

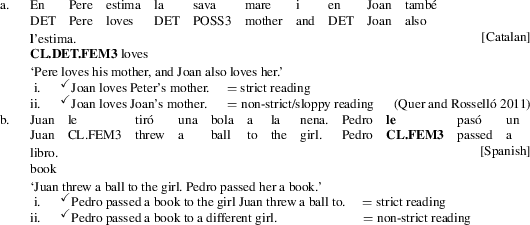

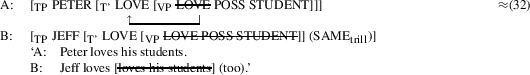

Before proceeding further, a note of caution must be issued: as an anonymous NLLT reviewer points out, Quer and Rosselló (2011) have challenged the observation that pronouns cannot have a non-strict readings. This seems to be true, for example, with the Romance object clitic below.

-

(i)

Incidentally, with a non-clitic pronoun, the sloppy reading disappears, so the account it seems needs to rely on the difference between the two types of elements:

-

(ii)

The exact nature of the phenomenon in Spanish and Catalan lies outside of the scope of this paper; it suffices to note, however, that while the sloppy reading of an overt clitic may be available, the quantificational one—the reading available in ASL as well as other languages argued to exhibit similar properties—never is:

-

(iii)

At any rate, as demonstrated in (23), pro allows neither.

-

(i)

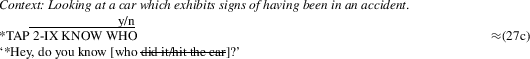

IX in ASL is often translated as a personal pronoun (but see Sect. 4.2.1); thus, we predict that if IX is used in lieu of Ø, the non-strict readings would disappear. In (i), glosses show that IX must refer back to the locus associated with Peter, not Jeff.

-

(i)

a-PETER LOVE POSS STUDENT, b-JEFF HATE {a-IX/*b-IX/*c-IX}

‘Peter loves his students but Jeff hates IX.’

However, this diagnostic is not usable for ASL. First, IX is never ambiguous in the same sense personal pronouns in English and Spanish in (23) are because is overtly realizes the semantic index and/or ϕ-features of the referent (see Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006 for an overview of proposals). In addition, recall that we are concerned with cases that where loci have not yet been assigned. However, if the locus of the NP serving as the referent of IX has not been assigned, the use of IX is ungrammatical. Finally, close examination of IX as a personal pronoun suggests that it is best described as a demonstrative. Demonstratives, in turn, do tend to produce strict readings only (except in the donkey-type environments), which is, perhaps, why the only reading available with a-IX is that Jeff hates Peter, not Peter’s students—Jeff hates ‘that person’(Koulidobrova and Lillo-Martin 2016).

-

(i)

KISS and SPANK are notoriously transitive; therefore, they are used here to make the point. However, as an anonymous reviewer points out, both KISS and SPANK are two-handed. This means that it is potentially possible that the non-dominant hand is serving an argument function in cases like (28). The paradigm remains the same with just as notoriously transitive but one-handed verbs F-I-X (a finger-spelled English loan) and HATE (a.k.a. VOMIT-HATE).

To reinforce this conclusion, compare (28) with the true ‘deep-anaphoric’ scenario in (i):

-

(i)

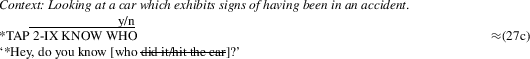

While my consultants judge the sentence as grammatical with the deferred ostension interpretation ‘Do you know who this is (i.e. this car belongs to)?,’ (i) is impossible on the relevant reading, indicated by the strike-through in the brackets.

-

(i)

Where precisely the verb moves is irrelevant here. In (34), the verb is schematized to have moved to T°, but the nature of the potential landing site is orthogonal to the claim advocated here, as long as the verb can move out of the VP.

While this section focuses on null objects exclusively, the arguments extend to null subjects as well. The claim then would be that the null subject results from V-raising vP-ellipsis. Test cases would be amended slightly, but the trail of argumentation would remain unchanged, and, it turns out, so would the outcome. Therefore, I limit the discussion here to null objects.

This account easily handles cases where the verb in (A) sentences is identical to the verb in (B) sentences as in (i).

-

(i)

However, the Copy Theory of Movement may create an independent complication for this view of (32): the VP retains a copy of the verb (albeit a phonologically null one). Therefore, on the analysis of (32), what we should find in the ellipsis site is actually [LOVE POSS STUDENT] instead, resulting in a contradiction. See Goldberg (2005) for the verbal identity requirement conditioning V-VPE.

-

(i)

It could be argued that SAME itself warrants further examination. For instance, it might be analyzed as simply also or a ‘deep’ anaphoric element best translated into do it/do the same thing (see Sect. 3.2). However, in such a case, the addition of SLOWLY should result in a grammatical sentence—something like Peter will also build {his/three} house(s) but slowly or Peter will do the same (thing) slowly. However, as (39c–d) show, the resulting sentence is ruled out. As discussed in Cecchetto et al. (2012), LIS behaves differently here. I thank an anonymous NLLT reviewer for pointing this out.

The test case here is Turkish: a language with subject- but not object-agreement, Turkish is claimed to show effects of argument ellipsis for objects but not subjects (Şener and Takahashi 2009).

While (47) and (49) schematize the null subject case, the analysis is identical with respect to object agreement (and lack thereof), with the relevant functional head being v°.

Saito (2007) assumes LF-Copying; there is nothing in the syntax in this position.

It should be noted that Saito (2007)—appealed to in the literature on the East Asian and some Romance and Altaic languages (cf. Takahashi 2010)—has met some criticism with regards to English. This is because the account predicts a possibility PP-/AP-/CP-ellipsis in English. To elaborate: it is standardly assumed that the English T° has ϕ-features and undergoes Agree with the argument of the verb. The ‘recycling’ of argument DP is excluded for the same reasons as in Spanish: the relevant uninterpretable feature of the DP is erased, and the DP cannot be ‘reused.’ However, neither the DP objects, nor other non-DP arguments face this problem. This now means that PP-/AP-/CP-ellipsis should be possible—a wrong prediction.

Consider, e.g., the English (i), involving, on standard accounts, NP-ellipsis. This ellipsis has been argued to be licensed by the head of this argument, D, realized as the possessive -’s and stranded (Saito and Murasugi 1990, i.a.):

-

(i)

I have read Bill’s book, but I haven’t read [John’s [

NPbook]]. (Jackendoff 1977)

As (i) demonstrates, ellipsis of a part of an argument is allowed in English, while the entirety of it is not. Matters are reversed for ASL.

-

(i)

It should be pointed out that some adjectives (e.g. color) allow stranding:

-

(i)

WANT BLUE

‘I want blue/the blue one.’

ASL is not alone here: a number of languages (including English) allow such stranding of color adjectives. The question, however, is how productive the phenomenon is. In this, ASL parallels French and English—outside of color (and, perhaps, size) adjectives, such stranding is impossible.

-

(i)

Technically, Tomioka does not use the term ‘ellipsis’ but, rather, ‘drop.’ However, for the present purposes, his claim subsumes ellipsis cases. This is also, essentially, what Hoji (1998) refers to as the indefinite pro, demonstrating that ‘sloppy’ reading of the null object, for example, is not exactly that.

The prediction of this approach is that a language with an overt article, irrespective of its phonological nullness, will disallow this type of NP drop in principle. Therefore, it must be the case that the null object in Modern Greek, Brazilian Portuguese, and Hebrew, argued to arise only in the absence of a D-element in the overt string must be derived differently (cf. Barbosa 2011 for the discussion of the argument-drop effects in these languages). Since these languages actually possess a lexical item corresponding to the ɩ-operator, the type-shift should be blocked.

Zimmer and Patschke (1990) view only a subclass of IX as corresponding to something like the English ‘the’: “signs that move slightly or not at all, never arc or jab, and most often point slightly upward” (p. 207). It should be noted that the authors also view this sign produced postnominally in the same terms. Importantly, however, for Zimmer and Patschke, this sign does not mark definiteness but, rather, specificity—a view that MacLaughlin (1997) offers various arguments against. While the issues that arise from the ensuing discussion pertain to the nature of prenominal IX, they deserve much more room than can be allotted in this paper. See Koulidobrova (2012b) for a further discussion.

Wolter (2006) points out that while many languages do not have a definite article, all languages examined thus far have demonstratives.

I thank Philippe Schlenker for bringing this to my attention.

A number of lexical items encoding familiarity in other Niger languages (both Chadic and Kwa) have been suggested to behave similarly (see Aboh 2010 for an overview).

Zooming out of the specifics of Akan and its immediate comparison with ASL, one other relevant observation must be noted: although various lexical items in Niger languages are often labeled ‘definite articles,’ a number of them (nυ included) have been argued to be something other than the D°. While the relevant lexical items in other Niger languages behave differently than they do in Akan, as Ajiboye (2005 [2008]) notes for Yoruba following Manfredi (1992), such ‘determiners’ behave more like deictics and demonstratives instead.

Thus, as an NLLT reviewer points out, the term ‘singular’ is pre-theoretic here; at the moment, no evidence is offered that the number is specified (namely that it is singular), only that plurality is not morphologically encoded on the noun. Therefore, it may be best to label these nouns ‘bare non-plurals.’ Koulidobrova (in progress) investigates this issue further.

Incidentally, Chierchia (1998) uses this property of nouns to argue for the argumental status of NPs in such languages.

The data in (74b) also offer evidence against Hoji (1998)-style analysis (according to which Ø is the null indefinite pronoun, akin to the English one): (i) is expected to be grammatical but it is not.

-

(i)

*1-IX WANT SMART Ø

‘*I want the smart

one.’

-

(i)

This constitutes another argument against the Tomioka (2003)-style account, which wrongly predicts that THREE <<et>et>> should be able to be stranded (see (52)).

One might imagine a variety of ways in which languages without D0 might encode the relevant semantics and thus invites interesting cross-linguistic inquiry (see Partee and Borschev 2007 lecture notes, i.a.).

References

Abner, Natasha. 2013. Gettin’ together a posse: The primacy of predication in ASL possessives. Sign Language and Linguistics 16(2): 125–156. Sign language syntax from a formal perspective: Selected papers from the 2012 Warsaw FEAST.

Abner, Natascha, and Thomas Graf. 2012. Binding complexity and the status of pronouns in English and American Sign Language. Presented at Formal and Experimental Advances in Sign Language Theory (FEAST) 2012, May 2012, Warsaw, Poland.

Aboh, Enoch. 2010. The morphosyntax of the noun phrase. In Topics in Kwa syntax, eds. Enoch O. Aboh and James Essegbey, 11–37. Dordrecht: Springer.

Ajiboye, Oladipo. 2005 [2008]. Topics on Yoruba nominal expressions. Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia. Saarbrücken, Germany: Verlag Aktiengesellschaft and Co.

Alexiadou, Anastasia, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 1998. Word order, V-movement and EPP-checking. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 16(3): 491–539.

AnderBois, Scott. 2011. Issues and alternatives. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Arkoh, Ruby, and Lisa Matthewson. 2013. A familiar definite article in Akan. Lingua 123: 1–30.

Bahan, Benjamin. 1996. Non-manual realization of agreement in American Sign Language. Doctoral dissertation, Boston University.

Bahan, Benjamin, Judy Kegl, Robert Lee, Dawn MacLaughlin, and Carol Neidle. 2000. The licensing of null arguments in ASL. Linguistic Inquiry 31(1): 1–27.

Barbosa, Pilar. 2009. Two kinds of subject pro. Studia Linguistica 63(1): 2–58.

Barbosa, Pilar. 2011. Partial pro-drop as null NP-anaphora. North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 40.

Barbosa, Pilar. 2013. Pro as a minimal NP: Towards a unified theory of pro-drop. http://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/001949.

Barlow, Michael, and Charles A. Ferguson. 1988. Agreement in natural language: Approaches, theories, descriptions. Stanford: Center for the Study of Language and Information.

Bernath, Jeffrey. 2009. Finding the DP in ASL. Paper presented at European Summer School of Language, Logic and Information (ESSLLI) 2009, Bordeaux, France.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Roumyana Pancheva. 2006. Implicit arguments. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 558–588. Oxford: Blackwell.

Boeckx, Cedric. 2012. Syntactic islands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Borer, Hagit. 1989. Anaphoric AGR. In The pro-drop parameter, eds. Osvaldo Jaeggli and Kenneth Safir. Dordrecht: Reidel Inc.

Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring sense. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bošković, Željko. 1994. D-structure, theta-criterion, and movement into theta-positions. Linguistic Analysis 24: 247–286.

Bošković, Željko. 2002. A-movement and the EPP. Syntax 5: 167–218.

Bošković, Željko. 2008. What will you have, DP or NP? North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 37. GLSA, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Bošković, Željko. 2009. More on the no-DP analysis of article-less languages. Studia Linguistica 63(2): 187–203.

Bošković, Željko. 2016. On clitic doubling and argument ellipsis: Argument ellipsis as predicate ellipsis. http://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/002955. Accessed 29 April 2016.

Bošković, Željko, and Serkan Şener. 2012. On Turkish NP. In Crosslinguistic studies on nominal reference: With and without articles, eds. Patricia Cabredo Hofherr and Anne Zribi-Hertz, 102–140. Leiden: Brill.

Braze, David. 2004. Aspectual inflection, verb raising and object fronting in American Sign Language. Lingua 114: 29–58.

Cardinaletti, Anna. 1994. On the internal structure of pronominal DPs. The Linguistic Review 11(3–4): 195–219.

Cardinaletti, Anna. 2004. Subjects, expletives, and the EPP. Journal of Linguistics 40(2): 457–460.

Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 2006. The syntax of quantified phrases and quantitative clitics. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 23–93. Oxford: Blackwell.

Cecchetto, Carlo, Alessandra Checchetto, Carlo Geraci, and Sandro Zucchi. 2012. The SAME constituent structure. Presented at FEAST 2012, Warsaw, Poland.

Chen, H.-T. Johnny. 2012. Null arguments in Mandarin Chinese and DP/NP parameter. Ms. University of Connecticut.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Reference to kinds across languages. Natural Language Semantics 2: 339–405.

Chomsky, Noam. 1977. On wh-movement. In Formal syntax, eds. Peter Culicover, Thomas Wasow, and Adrian Akmajian, 71–132. San Francisco, London: Academic Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1982. Some concepts and consequences of the theory of government and binding. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chung, Sandra. 2013. Syntactic identity in sluicing: How much and why. Linguistic Inquiry 44(1): 1–44.

Cokely, Dennis, and Charlotte Baker-Shenk. 1980. American Sign Language: The original Green books. Clerc Books: Gallaudet University Press.

Davidson, Kathryn. 2013. ‘And’ and ‘or’: General use coordination in ASL. Semantics and Pragmatics 6(3): 1–44.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2004. Number marking and (in)definiteness in kind terms. Linguistics and Philosophy 27: 393–450.

Diesing, Molly. 1992. Indefinites. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Elbourne, Paul. 2005. Situations and individuals. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Fillmore, Charles. 1969. Types of lexical information. In Studies in syntax and semantics, ed. Ferenc Kiefer, 109–137. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Frascarelli, Mara. 2007. Subjects, topics and the interpretation of pro: A new approach to the null subject parameter. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25: 691–734.

Frajzyngier, Zygmunt. 1996. Grammaticalization of the complex sentence: A case study in Chadic. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Frege, Gottlob. 1960 [1892]. On sense and reference. Reprinted in Translations from the philosophical writings of Gottlob Frege, eds. Peter Geach and Max Black. Oxford: Blackwell.

Fukui, Naoki. 1986. A theory of category projection and its applications. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Geist, Ljudmila. 2010. Bare singular NPs in argument positions: Restrictions on indefiniteness. International Review of Pragmatics 2: 191–227.

Geist, Ljudmila. 2013. Indefinite NPs without indefinite articles. Presented at the annual workshop on languages with and without definite articles. February 2013, Paris, France.

Gökgöz, Kadir. In preparation. Phi-‘agreement’ in American Sign Language. Ms. University of Connecticut/Central Connecticut State University.

Goldberg, Lotus. 2005. Verb-stranding VP ellipsis: A cross-linguistic study. Doctoral dissertation, McGill.

Gribanova, Vera. 2013a. Verb-stranding verb phrase ellipsis and the structure of the Russian verbal complex. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31(1): 91–136.

Gribanova, Vera. 2013b. A new argument for verb-stranding verb phrase ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 44(1): 145–157.

Grønn, Atle. 2006. Norwegian bare singulars: A note on types and sorts. In A Festschrift for Kjell Johan Sæbø: In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the celebration of his 50th birthday, eds. Torgrim Solstad, Atle Grønn, and Dag Haug. Oslo.

Hankamer, Jorge, and Ivan Sag. 1976. Deep and surface anaphora. Linguistic Inquiry 7(2): 391–428.

Heestand, Dustin, Xiang Ming, and Maria Polinsky. 2011. Resumption still does not rescue islands. Linguistic Inquiry 42: 138–152.

Heim, Irene, and Angelika Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hoji, Hajime. 1998. Null object and sloppy identity in Japanese. Linguistic Inquiry 29(1): 127–152.

Holmberg, Anders. 2005. Is there a little pro? Evidence from Finnish. Linguistic Inquiry 36(4): 533–564.

Holmberg, Anders. 2010. Null subject parameters. In Parametric variation: Null subjects in Minimalist theory, eds. Theresa Biberauer, Anders Holmberg, Ian Roberts, and Michelle Sheehan, 88–124. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1984. On the distribution and reference of empty pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 15: 531–574.

Huang, C.-T. James, and Barry C.-Y. Yang. 2013. Topic-drop and MCP. Presented at the 87th annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, January 2013, Boston, MA.

Ionin, Tania. 2010. An experimental study on the scope of (un)modified indefinites. International Review of Pragmatics 2: 228–265.

Ionin, Tania, and Ora Matushansky. 2006. The composition of complex cardinals. Journal of Semantics 23: 315–360. doi:10.1093/jos/ffl006.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1977. X − -syntax: a study of phrase structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Johnson, Kyle. 2009. Ellipsis. Presented at Hogeschool-Universiteit, Brussels, April 2009.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1969. Pronouns and variables. In Fifth regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS), eds. Robert Binnick, Alice Davison, Georgia Green, and Jerry Morgan. Vol. 5, 108–116. Chicago: University of Chicago, Department of Linguistics.

Koulidobrova, Elena. 2009. SELF: Intensifier and ‘long distance’ effects in ASL. European Summer School of Language, Logic and Information (ESSLI) 2009, July 2009, Bordeaux, France.

Koulidobrova, Elena. 2011. Null objects in ASL: The case of (indefinite) argument ellipsis. Presented at Formal and Experimental Advances in Sign Language Theory (FEAST) 2011, June 2011. Venice, Italy.

Koulidobrova, Elena. 2012a. When the quiet surfaces: ‘Transfer’ of argument omission in the speech of ASL-English Bilinguals. Doctoral dissertation, University of Connecticut.

Koulidobrova, Elena. 2012b. Parallelism revisited: The nature of the null argument in ASL as compared to the Romance-style pro. Sign Language and Linguistics 15(2): 259–270. doi:10.1075/sll.15.2.07.

Koulidobrova, Elena, and Diane Lillo-Martin. 2016. A ‘point’ of inquiry: The case of the (non-)pronominal IX in ASL. In The impact of pronominal form on interpretation, eds. Patrick Grosz and Pritty Patel-Grosz. Vol. 125 of Studies in generative grammar, 221–250. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.

Kuhn, Jeremy. 2016. ASL Loci: Variables or features? Journal of Semantics 33(3): 449–491. doi:10.1093/jos/ffv005.

Lillo-Martin, Diane. 1986. Two kinds of null arguments in American Sign Language. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 4(4): 415–444.

Lillo-Martin, Diane. 1991. Universal grammar and American Sign Language: Setting the null argument parameters. Netherlands: Kluwer.

Lillo-Martin, Diane. 1995. The point of view predicate in American Sign Language. In Language, gesture, and space, eds. Karen Emmorey and Judy Reilly, 155–170. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lillo-Martin, Diane, and Edward Klima. 1990. Pointing out difference: ASL pronouns in syntactic theory. In Theoretical issues in sign language research 1: Linguistics, eds. Susan Fischer and Patricia Siple, 191–210. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lillo-Martin, Diane, and Richard Meier. 2011. On the linguistic status of ‘agreement’ in sign languages. Theoretical Linguistics 37(3): 91–141.

Löbner, Sebastian. 1985. Definites. Journal of Semantics 2(4): 279–326.

MacLaughlin, Dawn. 1997. The structure of determiner phrases: Evidence from American Sign Language. Doctoral dissertation, Boston University.

Malamud, Sofia. 2012. Impersonal indexicals: One, you, man, and du. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 15(1): 1–48.

Manfredi, Victor. 1992. A typology of Yorùbá nominalizations. In MIT working papers in linguistics, eds. Chris Collins and Victor Manfredi. Vol. 17 of Kwa comparative syntax workshop, 205–217. Cambridge: MIT Press.

McCloskey, James. 2006. Resumption. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 94–117. Oxford: Blackwell.

McCloskey, James, and Ken Hale. 1984. On the syntax of person-number inflection in Modern Irish. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 1(4): 487–533.

Meier, Richard. 1990. Person deixis in American Sign Language. In Theoretical issues in sign language research, eds. Susan Fischer and Patricia Siple, 175–190. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Meir, Irit, Carol Padden, Mark Aronoff, and Wendy Sandler. 2007. Body as subject. Journal of Linguistics 43(03): 531–563. doi:10.1017/S0022226707004768.

Merchant, Jason. 2000. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands, and identity in ellipsis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 2013. Voice and ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 44: 77–108.

Miller, Karen, and Christina Schmidt. 2005. The interpretation of indefinites and bare singulars in Spanish child language. In 6th conference on the acquisition of Spanish and Portuguese as first and second languages, ed. David Eddington, 92–101. Somerville: Cascadilla.

Milsark, Gary. 1974. Existential sentences in English. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Neidle, Carol, Judy Kegl, Dawn MacLaughlin, Benjamin Bahan, and Robert Lee. 2000. American Sign Language: Functional categories and hierarchical structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Prospects and challenges for a clitic analysis of (A)SL agreement. Theoretical Linguistics 37(3/4): 173–187.

Nishiguchi, Sumiyo. 2009. Quantifiers in Japanese. In TbiLLC 2007, eds. Peter Bosch, David Gabelaia, and Jérôme Lang, 153–164. Berlin: Springer.

Oku, Satoshi. 1998. LF copy analysis of Japanese null arguments. Papers from the Regional Meetings. Chicago Linguistic Society 34(1): 299–314.

Otani, Kazuyo, and John Whitman. 1991. V-raising and VP-ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 22: 345–358.

Padden, Carole. 1989 [1983]. Interaction of morphology and syntax in American Sign Language. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, San Diego.

Partee, Barbara. 1987. Noun phrase interpretation and type-shifting principles. In Studies in discourse representation theory and the theory of generalized quantifiers, ed. Jeroen Groenendijk. Dordrecht: Foris.

Partee, Barbara, and Vladimir Borschev. 2007. Existential sentences, BE, and the Genitive of Negation in Russian. In Existence: Semantics and syntax, eds. Ileana Comorovski and Klaus von Heusinger, 147–190. Dordrecht: Springer. https://udrive.oit.umass.edu/partee/ParteeBorschevNancy.pdf.

Petronio, Karen. 1995. Bare noun phrases, verbs, and quantification in ASL. In Quantification in natural languages, eds. Emmon Bach, Eloise Jelinek, Angelika Kratzer, and Barbara Partee. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Quadros, Ronice Muller de, and Diane Lillo-Martin. 2010. Clause structure. In Sign languages: A Cambridge language survey, ed. Diane Brentari. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Quer, Josep. 2011. Licensing of empty arguments in sign languages. Presented at the Colloquium on Generative Grammar (CGG), Seville, Spain.

Quer, Josep, and Joana Rosselló. 2011. On sloppy readings, ellipsis and pronouns: Missing arguments in Catalan Sign Language (LSC) and other argument-drop languages. Ms. ICREA-Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Universitat de Barcelona.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1983. Coreference and bound anaphora: A restatement of the anaphora questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 6: 47–88.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1982. Issues in Italian syntax. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1986. Null objects in Italian and the theory of pro. Linguistic Inquiry 17(3): 501–557.

Roberts, Ian. 2010. A deletion analysis of the null subjects. In Parametric variation: Null subjects in minimalist theory, eds. Theresa Biberauer, Anders Holmberg, Ian Roberts, and Michelle Sheehan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, Ian, and Andres Holmberg. 2010. Parameters in minimalist theory. In Parametric variation: Null subjects in minimalist theory, eds. Theresa Biberauer, Anders Holmberg, Ian Roberts, and Michelle Sheehan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ross, John. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Russell, Bertrand. 1905. On denoting. Mind 14: 479–493.

Sakamoto, Yuta. 2013. Disjunction as a new diagnostic for (argument) ellipsis. Ms., University of Connecticut.

Saito, Mamoru. 2007. Notes on East Asian argument ellipsis. Language Research 43(2): 203–227.

Saito, Mamoru, and Keiko Murasugi. 1990. N′-deletion in Japanese: A preliminary study. Japanese/Korean Linguistics 1: 285–301.

Sandler, Wendy, and Diane Lillo-Martin. 2006. Sign language and linguistic universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2009. Donkey anaphora in sign language II: The presuppositions of pronouns. North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 2009, Special Session on Pronouns.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2011. Quantifiers and variables: Insights from sign language (ASL and LSF). In Formal semantics and pragmatics: Discourse, context, and models, eds. Barbara Partee, Michael Glanzberg, and Jurgis Skilters. Manhattan: New Prairie Press. The Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication 6.

Schwarz, Florian. 2009. Two types of definites in natural language. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Şener, Serkan, and Daiko Takahashi. 2009. Argument ellipsis in Japanese and Turkish. Presented at the Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics (WAFL 6), Nagoya, Japan.

Sharvy, Richard. 1980. A more general theory of definite descriptions. Philosophical Review 89: 607–624.

Sheehan, Michelle. 2006. The EPP and the null subject in Romance. Doctoral dissertation, Newcastle University.

Strawson, Peter. 1950. On referring. Mind 59: 320–344.

Takahashi, Daiko. 2008. Quantificational null objects and argument ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 307–326.

Takahashi, Daiko. 2010. Argument ellipsis, anti-agreement, and scrambling. Ms., Tohoku University.

Thompson, Robin, Karen Emmorey, and Robert Kluender. 2006. The relationship between eye-gaze and verb agreement in American Sign Language: An eye-tracking study. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 24(2): 571–604.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2003. The semantics of Japanese null pronouns and its cross-linguistic implications. In The interfaces: Deriving and interpreting omitted structures, eds. Kerstin Schwabe and Susanne Winkler. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Vendler, Zeno. 1967. Verbs and times. In Linguistics in philosophy, 97–121. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Wolter, Lynsey. 2006. That’s that: The semantics and pragmatics of demonstrative noun phrases. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Wood, Sandra. 1999. Semantic and syntactic aspects of negation in ASL. MA thesis, Purdue University.

Zimmer, June, and Cynthia Patschke. 1990. A class of determiners in ASL. In Sign language research: Theoretical issues, ed. Ceil Lucas, 201–210. Washington: Gallaudet University Press.

Acknowledgements

The paper has benefitted from the comments by numerous people. For valuable feedback and patience, I am particularly grateful to Željko Bošković, Diane Lillo-Martin, Jon Gajewski, Philippe Schlenker, Kyle Johnson, members of Sign Language Lab at the University of Connecticut, participants of FEAST 2011, and the Natural Language and Linguistic Theory reviewers. This work would not have been possible without the deaf and hearing language consultants at the American School for the Deaf, Gallaudet University, University of Connecticut, and Central Connecticut State University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

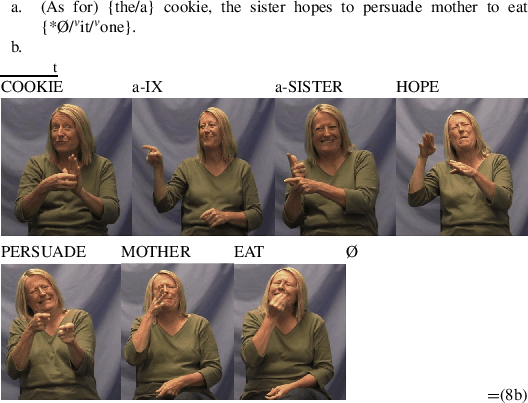

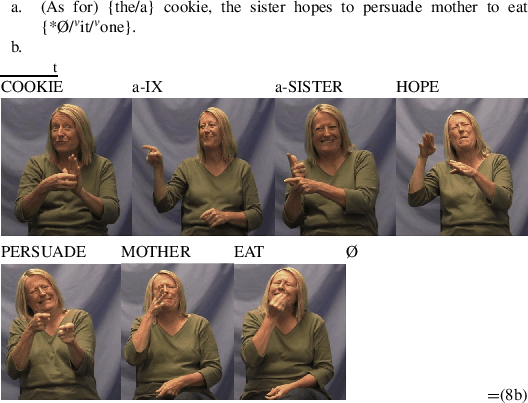

Appendix: English = a.; ASL = b.

Appendix: English = a.; ASL = b.

-

(87)

-

(88)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koulidobrova, E. Elide me bare. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 35, 397–446 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-016-9349-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-016-9349-5