Abstract

We present two cases of morphophonological alternations in the plural of nouns, one from French and one from Brazilian Portuguese. In both of them, monosyllabic items are protected from right-edge alternations more than polysyllabic items are, an asymmetry we attribute to privileged protection of initial syllables. We implement the analyses of the two languages using constraint-based grammars that take trends learned across the lexicon and predict the treatment of nonce words. Five large-scale nonce word tasks confirm the productivity of the trend in both languages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Initial syllable faithfulness

In this paper, we examine morphophonological alternations found in the plural of French and Brazilian Portuguese nouns, and propose that both cases are governed by a discrete binary distinction between monosyllables and polysyllables, specifically implemented in terms of initial syllable faithfulness as a means of protecting the former but not the latter from alternations. While much research has shown that speakers have detailed knowledge about the distribution of irregular morphophonological trends in their lexicon, and that this knowledge is applied to nonce words (Zuraw 2000; Ernestus and Baayen 2003; Albright and Hayes 2003, among many others), the degree of granularity of the mechanisms that regulate grammatical generalization to novel forms remains an open question.

One family of hypotheses is that speakers use discrete formal primitives such as syllable count or feature-markedness constraints, as in frameworks such as Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky 1993/2004), and that constraint rankings may distill the lexical statistics in terms of a grammatical encoding that can be applied to nonce words. This characterizes the constraint cloning approach (Pater 2006, 2008b; Coetzee 2008; Becker 2009; Becker et al. 2011) and the UseListed approach (Zuraw 2000; Hayes and Londe 2006; Becker et al. 2012). While these authors differ in their commitment to the universality of the constraint set and its naturalness, it is often implicitly assumed that universality and naturalness are guiding principles, if not ironclad rules. In the present paper, we demonstrate that in both French and Brazilian Portuguese, monosyllables are protected from plural alternations, whereas polysyllables are impacted more strongly. We attribute this asymmetric size effect to initial syllable faithfulness constraints (Trubetzkoy 1939; Steriade 1994; Beckman 1997, 1998; Casali 1998; Barnes 2006; Jesney 2011; Becker 2009; Becker et al. 2011). We contrast our discrete analysis with hypotheses that use fine-grained, gradient approaches that refer to phonetic duration, neighborhood density, and similar measures.

The case studies at hand are two processes affecting plural formation in what historically were lateral-final nouns in French and Portuguese. Both French and Portuguese have undergone a series of diachronic changes affecting the realization of final laterals in both singular and plural forms, and the telescoping of some of these changes has led to an irregular set of alternations. The extension of these alternations to novel words is limited in French but as we demonstrate, can be elicited in experimental settings, whereas in Portuguese it is strongly productive outside the laboratory as well. By hypothesis, the generalization of the morphophonological process of plural formation to novel words has fallen along grammatically-defined contours, in which number of syllables and vowel quality play a role within the context of discretely-defined constraints on the process.

The paper is structured as follows: We start with a study and analysis of the French lexicon in Sect. 2, and show how the analysis predicts participants’ treatment of novel words in Sect. 3. Portuguese receives the same treatment in Sect. 4 and Sect. 5. In Sect. 6, we discuss alternative explanations to the initial syllable effect, and Sect. 7 concludes.

2 A study of alternations in the French lexicon

The point of departure for the first set of studies is based on French plural morphology as measured in the lexicon, where we demonstrate that in the real words of French, alternations impact polysyllables more than monosyllables. This size-based asymmetry is a novel observation, to our knowledge. The trend is statistically significant, and we offer an analysis that captures the trend grammatically by appealing to initial syllable faithfulness.

2.1 The French irregular plural

The plural normally has no distinct morphological marking in French nouns, e.g. 〈nom〉 [nõ] ‘noun’ is identical in the singular and plural, with number only marked on determiners and certain verbs. Some nouns that end in [l] or [j], however, have a phonologically distinct plural that impacts the stem, as shown in (1).

In addition to the nominal alternations shown in (1), the same [al] → [o] alternation is also fairly common for [al]-final adjectives, e.g. [lwajal ∼ lwajo] ‘loyal’. The adjectives show the same kind of lexically-specific variation that nouns do, e.g. [nazal ∼ nazo] ‘nasal’ vs. [naval ∼ naval] ‘naval’.

-

(1)

Unfaithful, alternating French pluralsFootnote 1

alternation

singular

plural

a.

[al] → [o]

mal

mo

‘evil’

bokal

boko

‘jar’

Ʒuʁnal

Ʒuʁno

‘newspaper’

b.

[aj] → [o]

baj

bo

‘lease’

tʁavaj

tʁavo

‘work’

supiʁaj

supiʁo

‘basement window’

These alternations contrast with near-minimal pairs of nouns and adjectives that keep the same form in the singular and in the plural, as in (2). In addition, some variable nouns and adjectives can take either kind of plural, e.g. [val] ‘valley’, [beʁkaj] ‘home’. The alternations do not always impact homophonous nouns and adjectives equally in our data, e.g. the adjective [final ∼ fino] ‘final’ always alternates, but the corresponding noun is variable [final ∼ final/fino] ‘end’.

-

(2)

Faithful, non-alternating French plurals

singular

plural

a.

bal

bal

‘ball’

ʃakal

ʃakal

‘jackal’

kaʁnaval

kaʁnaval

‘carnival’

b.

maj

maj

‘hammer’

detaj

detaj

‘detail’

evᾶtaj

evᾶtaj

‘fan’

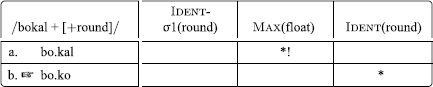

Historically, plural alternations were part of a larger pattern of l-vocalization (Pope 1952). French had a plural suffix [s], and general vocalization of velarized laterals, including the preconsonantal laterals, which were uniformly velarized. Thus the paradigm [mal ∼ maɫs] ‘evil, sg./pl.’ of Gallo-Roman (7th century) turned to [mal ∼ maus] and then monophthongized to [mal ∼ mos] by the end of Early Old French (12th century). Soon after, the plural suffix was lost in all but liaison contexts, producing the modern [mal ∼ mo]. The [j]-final nouns in (1b)–(2b) had a palatal lateral that velarized preconsonantally, and thus followed a similar path, from e.g. [baʎ ∼ baʎs] ‘lease’ to [baʎ ∼ baɫs] to [baʎ ∼ baus] to [baʎ ∼ bos] and with the loss of the plural suffix, [baʎ ∼ bo]. The simplification of the palatal lateral in the 18th century produced the modern [baj ∼ bo] (Pope 1952; see also Bennett 1997).

Up until Early Old French (12th century), all lateral-final nouns were affected without exception, including, e.g. [bal ∼ bos] ‘ball’, now [bal ∼ bal] (Pope 1952). Subsequently, some lexical items started losing the alternation, either keeping the lateral in both forms, like [bal], or losing it in both, like [ʃəvø] ‘hair’, originally [ʃəv εl ∼ ʃəvø]. Why some items kept the alternations and others did not is unknown. It is often suggested that loss of alternation starts with infrequent items (see e.g. Bybee 1995, 2001). However, as we will see in Sect. 2.2, the alternations were mostly lost in short words, and those are generally more frequent. From the time of Modern French (16th century) and onwards, neologisms and loanwords making their way into the language do not alternate, e.g. [ʃakal] ‘jackal’ from Turkish, [mistʁal] ‘the mistral wind’ from Provençal. Similarly, all modern loanwords are non-alternators. The alternation became effectively frozen, or unproductive.

In concluding this overview of French plural morphology, we note that in addition to the [al/aj]-final nouns discussed above, only five other nouns have plurals that are different from their singulars: [sjεl] ‘sky’, which in addition to the regular plural [sjεl] ‘skies’, may still be associated with the plural [sjø] ‘heavens’, [œj] ‘eye’, which has the suppletive plural [(z)jø], and the three fricative-final nouns [œf ∼ ø] ‘egg’, [bœf ∼ bø] ‘bull’, and [ɔs ∼ o] ‘bone’, which lose their final fricative. We see, then, that the plural morphology of French is overall rather regular, and all plurals that are audibly different from their singular end in [o] or [ø]. The situation is even simpler in feminine nouns, which never change in the plural. Finally, we mention that [l/j] alternations affect five adjectives that acquire a final [l] or [j] in the feminine and before vowel-initial singular nouns (i.e., liaison contexts; for a recent review of liaison, see Côté 2011): [fu ∼ fɔl] ‘crazy’, [mu ∼ mɔl] ‘soft’, [bo ∼ bεl] ‘beautiful’, [nuvo ∼ nuvεl] ‘new’, and [vjø ∼ vjεj] ‘old’. Before a vowel-initial noun like [ami] ‘friend’, these adjectives give rise to what looks like plural alternations, e.g. [vjεj ami] ‘old friend’ ∼ [vjø z ami] ‘old friends’. Before a consonant-initial noun, these adjectives remain unchanged in the plural.

2.2 Trends in the French irregular plural

To assess the distribution of the alternations among the real words of French, we extracted all the masculine [al/aj/εl/εj]-final nouns and adjectives from Lexique (New et al. 2001), an electronic dictionary of French that lists 143,000 words. Since alternations with [ε] are limited to the single word [sjεl] ‘sky’, we focused on the 672 [al/aj]-final items. A native speaker of French reviewed all of the monosyllabic [al/aj] items and a random sample of the polysyllabic ones, and classified all of the items for which they knew the plural as alternating, non-alternating, or variable. Items without a known plural were discarded, leaving 16 monosyllables and 102 polysyllables, for a total of 118 masculine [al/aj]-final nouns and adjectives (listed in Appendix A). Since our focus is on the difference between monosyllables and polysyllables, there was little benefit in increasing the number of polysyllables in our sample. The results are shown in Fig. 1, where it is evident that the alternations impact polysyllabic [al/aj]-final items more than monosyllabic ones. The dataset is available at http://becker.phonologist.org/projects/FrenchPortuguese/.

To measure the strength and reliability of the patterns seen in Fig. 1 and to make predictions about nonce words, we fitted a logistic regression model using the glm function in R (R Development Core Team 2016). The dependent variable was a binary distinction between alternating and non-alternating plurals. Variable words, which can take either kind of plural (10 of the 118 items), were counted as non-alternators; we also tried counting them as alternators, which led to nearly identical results (cf. our MaxEnt analysis below, which allows the variability to be modeled). The predictors used were final consonant, a binary factor that contrasted [l] and [j]; monosyllabic, a binary factor that contrasted monosyllables with polysyllables; token frequency (taken from Lexique and log-transformed); and neighborhood density (calculated as explained in Sect. 6 below). A model with consonant and token frequency was significantly improved by addition of monosyllabic (anova likelihood test, \(\upchi^{2}(\mathit{1}) = 10.6\), p < .005). None of the interactions made a significant improvement, nor did neighborhood density.Footnote 2 The final model, in Table 1, enjoys low collinearity (κ = 1.6).

The model in Table 1 shows that final [l] is conducive to significantly more alternations than final [j], frequent items are conducive to significantly more alternations than infrequent items, and polysyllables are conducive to significantly more alternations than monosyllables. In other words, monosyllables are protected from alternations, and this effect is predicted to apply to novel items. Neighborhood density, however, is not a significant predictor of alternations in the lexicon. This statistical model, based on the real words of French, predicts that a novel word of French will be more likely to alternate if it ends in [al] rather than [aj]. Even more strongly, it predicts that a nonce word is more likely to alternate if it is polysyllabic. These predictions are tested with three experiments in Sect. 3 below, where we will see that the weaker effect of the final consonant is not extended to nonce words, but the predicted difference between monosyllables and polysyllables is borne out strongly and clearly. Token frequency, while relevant to the existing words of the language, is irrelevant to novel words, which are all equally new to speakers.

2.3 Initial syllable faithfulness protects monosyllables

We have seen that the [al/aj → o] alternation impacts a larger proportion of polysyllables than monosyllables in the lexicon; in Sect. 3, we will also see that speakers represent this trend in their grammar, as evidenced by the fact that they extend it to novel items. We propose that initial syllable faithfulness is responsible for the effect (Trubetzkoy 1939; Steriade 1994; Beckman 1997, 1998; Casali 1998; Barnes 2006; Jesney 2011; Becker 2009; Becker et al. 2011, 2012). In polysyllables like [bo.kal ∼ bo.ko] ‘jar’, the initial syllable [bo] stays intact; thus, the alternation only violates general faithfulness, and there is no violation of initial syllable faithfulness. In a monosyllable like [mal ∼ mo] ‘evil’, however, the alternation impacts the initial syllable, and thus violates both general faithfulness and initial syllable faithfulness.

As discussed in Sect. 2.1 above, the alternation arose from a series of natural steps, including l-vocalization, monophthongization of [au] to [o], and loss of coda [s]. The alternation is no longer natural, since the disappearance of the plural suffix (represented only in the orthography) removed the environment that conditions the change. The change itself is no longer natural either, especially in the case of [aj → o], where [aj] could plausibly fuse to [e], but not to [o]. It should be noted, however, that the alternation does apply to the natural class of continuant sonorants. While French has the continuant sonorants [w] and [ɥ] in addition to [l] and [j], the former are not allowed word-finally (except for the interjection [waw] ‘wow’). Thus, all the continuant sonorants that are allowed word-finally in nouns participate in the alternation (unless one treats the fricative [ʁ] as a liquid due to its distribution in clusters).

We present our synchronic analysis of the French plural in three parts. First, Sect. 2.3.1 uses the autosegmental theory of mutation (Wolf 2007) to cause the [al/aj→o] change. Then in Sect. 2.3.2, the UseListed approach allows established lexical items to maintain a stable plural, while simultaneously allowing lexical statistics to project probabilistically to novel items. Finally, in Sect. 2.3.3, initial syllable faithfulness captures the resistance of monosyllabic items to the [al/aj→o] change.

2.3.1 Alternation caused by a floating [+round]

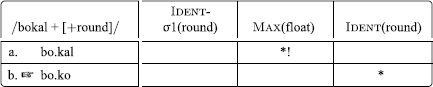

We propose that the plural affix is a floating [+round] feature that docks on the stem’s final [a], following Wolf’s (2007) autosegmental theory of mutation. The feature [−low] is not needed in the underlying representation of this affix, as markedness constraints ban a [+low, +round, +back] vowel in French. The floating affix is required to dock by Max(float), which in turn causes the stem to surface unfaithfully, changing the lowness and roundness of the stem’s final vowel, and thus creating violations of Ident(round) and Ident(low). Either of these Ident constraints can be sensitive to being in the word-initial syllable; we choose Ident(round) here.

As seen in (3)–(4), Max(float) is outranked by initial syllable faithfulness, preventing monosyllables from alternating. Polysyllables are allowed to alternate, since Max(float) outranks general faithfulness.

-

(3)

[bal ∼ bal] ‘ball’ is protected from alternation by Ident-

(round)

(round)

-

(4)

[bo.kal ∼ bo.ko] ‘jar’ allows the floating /[+round]/ to dock

The winner [bo.ko] in (4) needs to be more optimal than other, more faithful candidates, such as [bo.kol]. Following Wolf’s (2007: Sect. 4.1) analysis of DhoLuo, where alignment constraints force deletion, we use Align-R(affix, stem), a constraint that requires right-alignment of the affixal [+round] with the stem, outranking Max(approx), a constraint that bans deletion of sonorant continuants, as see in (5).

-

(5)

Root-final consonant deleted in [bo.kal ∼ bo.ko] ‘jar’ due to Align-R(affix, stem) ≫ Max

The complete analysis must also prevent the non-low vowels of the language from alternating, e.g. */gil + [+round]/ → *[gy]. We exclude the front unrounded vowels [i, e, ε, ε̃] with a faithfulness constraint that is specific to front vowels, Ident(round)/front (independently needed in this language, which contrasts roundness on front vowels only). We exclude the round vowels [u, o, ɔ, ̃ɔ, y, ø, œ] with *VacDoc (Wolf 2007), a constraint that penalizes the vacuous docking of a [+round] feature on a round vowel. The remaining non-front, non-round vowel, [ᾶ], is exceedingly rare before word-final sonorants, i.e. the constraint *[ᾶ][+son]# is generally respected in the language, and removes potential targets for the floating [+round]. Alternatively, one could enlist *Map constraints (Zuraw 2013) to rule out the unattested mappings.Footnote 3

To prevent the deletion of final consonants other than [l] and [j], e.g. */gak + [+round]/ → *[go], we employ Max(obstruent) and Max(nasal) to block the alternations from words that do not end in a sonorant continuant. It is thus safe to allow the floating round feature to attach to any stem in the language; the analysis limits the possibility of docking to [al/aj]-final items.

In the lexicon, [l] is more deletable than [j]; we can incorporate this fact into our analysis by further relativizing Max to the particular type of deleted segment, i.e. introducing Max(glide), a constraint that penalizes the deletion of [j] but not [l]. As we will see in Sect. 3, however, speakers failed to extend the greater deletability of [l] to nonce words. We propose that speakers are biased against learning a discontinuous treatment of the sonority scale: since French prevents deletion of low sonority segments (obstruents and nasals), learners expect the deletion pattern to continue to follow the sonority scale, making liquids either less deletable or as deletable as glides, but not more deletable. The French lexicon offers a disfavored pattern, and speakers leave it unlearned. Such “surfeit of the stimulus” (Becker et al. 2011, 2012) cases, or anti-Universal patterns, would be available to purely statistical learners that are not equipped with the biases that humans bring to the table.

One could imagine that speakers would learn to prefer [al→o] over [aj→o] by deploying a markedness constraint against final [al] or final [l]; however, given that final [(a)l] is extremely common in French across the entire lexicon, it is hard to see how it could be assigned a sufficiently large weight to tip the scale.Footnote 4 We return to the question of the final consonant in Sect. 2.3.4 and Sect. 3.4.

2.3.2 UseListed protects established lexical items

Most existing lexical items in our data have an established plural. For example, the plural of [bokal] ‘jar’ is normally the unfaithful [boko], while the faithful plural is practically never attested for this word. Novel items and infrequent items are often subject to more variation, e.g. both plurals are attested for [val] ‘valley’ (see Sect. 2.1). The UseListed approach (Zuraw 2000; Hayes and Londe 2006; Becker et al. 2012) is specifically designed to account for the difference between established and novel items, as seen in a variety of languages. A probabilistic grammar is created based on the statistical trends in the existing lexical items, but these items are protected from the same trends by the UseListed constraint. The original proposal in Zuraw (2000) used a stochastic version of Optimality Theory, but because stochastic OT was since discovered to be intractable (Pater 2008a, a.o.), we use the mathematically solid Maximum Entropy approach (Goldwater and Johnson 2003; Hayes and Wilson 2008; White 2014), implemented using Hayes and Wilson’s (2008) MaxEnt Grammar Tool.Footnote 5

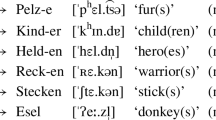

A MaxEnt grammar is a multinomial logistic regression model, and thus is quite similar to the binary logistic regression model we presented in Table 1; both models use the probability of the alternating plural as the dependent variable.Footnote 6 Using the MaxEnt Grammar Tool with its default settings (μ = 0, σ = 100,000), we trained the grammar on the probabilities of the alternating plurals in the lexicon, which included the 118 [al/aj]-final words from Sect. 2.2, and a sample of 100 [εl/εj]-final words from Lexique. Five constraints were used in the analysis: four of these are seen in the tableau in (6), with the weights assigned to them by the MaxEnt grammar tool, while the fifth, Ident(round), was assigned a weight of zero, i.e. it made no numerical contribution to the analysis. The harmony (ℋ) of each plural is the sum of multiplying each violation mark by the weight of the violated constraint; this harmony is then exponentiated, and dividing these exponents by their sum in each tableau yields the expected probability. The tableau in (6) shows two plurals for the nonce monosyllabic singular [gnal]: the faithful plural [gnal] and the alternating [gno]. The expected probability of the alternating monosyllabic plural [gno] is 35 %, less than that of the faithful plural.

-

(6)

MaxEnt prediction for an [al]-final monosyllable

To summarize, the MaxEnt analysis is trained on the plurals of real words of French and uses their distribution to calculate constraint weights. While the plurals of existing words are protected by UseListed, the plurals of nonce words are assigned a probability based on their weighted violations of the constraints in (6). The constraint UseListed was not used during training, and thus was not assigned a weight by the MaxEnt tool. Its weight can be assumed to be arbitrarily high.

2.3.3 Protection of monosyllables

We have seen in (6) that the [a→o] change in the nonce word [gnal ∼ gno] violates Ident- (round), since the stem change impacts the word’s first (and only) syllable. In contrast, the same [a→o] change in a nonce polysyllable such as [guval ∼ guvo] does not violate Ident-

(round), since the stem change impacts the word’s first (and only) syllable. In contrast, the same [a→o] change in a nonce polysyllable such as [guval ∼ guvo] does not violate Ident- (round), since the initial syllable [gu] is left unchanged (7). As a result, the predicted probability of the alternation in an [al]-final polysyllable with the given constraint weights is 0.66, and more likely than the faithful form, in contrast to tableau (6).

(round), since the initial syllable [gu] is left unchanged (7). As a result, the predicted probability of the alternation in an [al]-final polysyllable with the given constraint weights is 0.66, and more likely than the faithful form, in contrast to tableau (6).

-

(7)

MaxEnt prediction for an [al]-final polysyllable

It is worth discussing the differences between an account based on protection of initial syllables, as proposed here, and one based on specific protection of monosyllables. While the two kinds of protection overlap completely in the cases we examine in this paper, the predictions diverge in other cases. For example, the differential protection of codas in the initial and non-initial syllables of polysyllabic words in Tamil (Beckman 1997, 1998) does not single out monosyllables as special. Conversely, a hypothetical case of prefixation that impacts the left edge of polysyllables but not monosyllables, if observed, would require a protection of monosyllables, and would not be amenable to a treatment in terms of initial syllable protection. While cases of monosyllable-specific faithfulness are uncommon in the literature, some relevant evidence may come from Kirk and Demuth (2006), an acquisition study in which children showed higher accuracy for coda consonants in monosyllabic words vs. iambic or trochaic disyllabic words. We adopt initial syllable faithfulness here for its broader coverage of the cases that are known to us and the majority of cases that are described in the literature, while fully acknowledging that the specific set of results here could in fact be handled entirely with monosyllabic-specific constraints.

2.3.4 Summary

The proposed analysis uses a floating [+round] plural suffix, which allows the alternation to occur as a synchronic morphophonological process. The floating feature can be safely attached to any given noun or adjective, since the grammar only allows the feature to dock on [al/aj]-final words; other words are protected from change with a family of faithfulness constraints.

A weighted constraint MaxEnt grammar is trained on the established words of the language to assign constraint weights, and uses these weights to predict the probability of alternation of novel words. When the alternation impacts a monosyllable, it incurs a violation of initial syllable faithfulness, which decreases the predicted acceptability of the alternation. In Sect. 3 below, we show that speakers extend this differential treatment of monosyllables from the words in their lexicon to nonce words.

Our analysis strongly penalizes the alternation of [εl/εj]-final nouns using Ident(round)/front, a constraint that is independently needed in this language, which contrasts rounding on front vowels. We will see that participants strongly reject the alternation with [ε].

In the lexicon, [l] is more deletable than [j], which the analysis captures with a Max(glide) constraint that penalizes the deletion of [j]. In our experiments, however, participants do not seem to disfavor the deletion of [j]. If indeed one concludes that [l] and [j] are equally deletable, the model can be revised to diminish the effect of Max(glide), keeping its weight closer to zero using a Bayesian prior (cf. similar use of priors in MaxEnt models in Wilson 2006, White 2014, a.o). In the next section, we assess the extent to which speakers have generalized the trends found throughout the lexicon when it comes to governing the treatment of alternation in nonce words.

3 Nonce testing the French plural

The irregular plurals of French have received little attention in the literature, perhaps due to a prevalent intuition about their lack of productivity. Indeed, the alternation is synchronically unnatural, and does not seem to extend to loanwords. The number of [al/aj]-final monosyllables is rather small (n = 16), and thus might not intuitively suggest overwhelming evidence for their protection. We present a series of three experiments that establish that French speakers do extend the alternation to nonce words, and in particular, strongly protect the monosyllabic ones.

In Experiment 1 and Experiment 2, we asked participants to choose between a faithful plural and an unfaithful plural. The choice is presented on a scale of 1–7 in Experiment 1, and binarily in Experiment 2. In both experiments, the nonce words are presented auditorily using naturally produced speech. Additionally, in Experiment 2, participants were asked to rate the singular before they judge the plural. In both experiments, monosyllables were protected from alternation.

In the naturally produced materials of Experiments 1 and 2, the phonetic duration of the final [al/aj] sequences is inversely proportional to the duration of the whole word. Thus, the [al] of the short word [gnal] is phonetically longer in duration than the [al] of longer word [guval]. Increased segmental duration has been suggested as a source of protection from alternations, thus making the [al] of monosyllables less likely to change to [o] (see Sect. 6). In Experiment 3, we switch from naturally recorded stimuli to synthesized stimuli that keep segmental duration constant, i.e. the [al] of [gnal] and the [al] of [guval] were identical in duration. Participants nonetheless protected monosyllables; the implications are discussed further in Sect. 6.

3.1 Experiment 1: Scalar judgments

3.1.1 Participants

The participants were recruited online using word of mouth, and volunteered their time and effort without compensation. Data was gathered from 185 people who completed the survey and self-identified as being born in France and being at least 18 years old; the rest was discarded. The server logs indicate that these 185 participants took on average 4 minutes to complete the experiment (range 2–17 minutes; median 4). The participants reported an average age of 36 (range 18–74, median 32). According to self-reports, 116 females and 65 males completed the experiment; 4 did not answer this question. 83 participants listed no other language spoken, or indicated that they are monolingual. Of those who listed other languages, 76 indicated some knowledge of English, 18 Spanish, 15 German, and small numbers of other languages.

3.1.2 Materials

We created a total of 100 [l/j]-final items: 66 items with [a] in their final syllable (36 monosyllabic and 30 polysyllabic) and 34 items with [ε] (18 monosyllabic and 16 polysyllabic); recall that alternations in the lexicon are largely limited to [a] as compared to [ε], and we included the latter as a baseline for comparison. All nonword items were made in pairs, with [l] in one member and [j] in the other, e.g. [snal, snaj]. The items’ onsets were designed to span a wide range of phonotactic wellformedness, from extremely common onsets like [d] and [ʁ] to extremely uncommon ones like [sn] and [spʁ] (see discussion of this point in Sect. 6). The full list of items, with by-item results, is in Appendix B. 12 loanwords from English were used as fillers, e.g. [stεk] ‘steak’, [dolaʁ] ‘dollar’.

The items were recorded by a phonetically trained male native speaker of French in his twenties from the Ferté-Bernard region (∼100 miles from Paris) who was naive to the purpose of the experiment. The list included each noun in the faithful plural (which in French is identical to the singular) and the unfaithful plural, which replaced [al, aj, εl] with [o] and [εj] with [ø]. The recording was made in a quiet room into a Macintosh computer. The full list was recorded in three randomly generated orders. The best token of each item was chosen and converted to mp3 format. The recordings were not manipulated in any other way, other than normalizing the intensity with Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2015), and sounded natural.

3.1.3 Procedure

The experiment was run in Experigen (Becker and Levine 2012), and presented to the participants over the internet, using the web browser of the participant’s choice. The web server executed a random selection of materials for each participant, choosing a total of 20 items: 12 target items and 8 fillers. The experiment started with the sample item [dal], which we include in the analysis.

In addition to [dal], the 12 selected target items consisted of six monosyllables and six polysyllables, where each size included 3 [al]-final, 1 [aj]-final, 1 [εl]-final, and 1 [εj]-final items. The choice of more items containing [a] than [ε] reflects our expectation for a greater rate of alternations in the former. The choice of more [al] than [aj] approximates the greater prevalence of [al] in the lexicon. An additional 8 fillers were chosen randomly.

To make sure that the items were treated by speakers as masculine nouns, 20 frame sentences were created (recall that feminine nouns do not alternate). Each frame contained two phrases: the first included a placeholder for a singular noun, and the second included a placeholder for the plural form. Each frame contained at least one determiner or adjective that has phonologically distinct masculine and feminine forms, e.g. [gʁi] ‘gray.masc’, which is distinct from [gʁiz] ‘gray.fem’. These 20 frames were randomly paired with the 12 target items. Frame sentences were created for each of the 12 fillers.

Before the experiment began, each participant was introduced to the made-up item [dal], and was asked to indicate their preference between a faithful plural and an alternating plural, presented in French as a choice between “pluriel en s” and “pluriel en x”, referring to French orthography, which marks regular plurals of l/j-final nouns with 〈s〉 and vowel-changing irregular plurals with 〈x〉. In the following screen, the item [dal] appeared in its frame sentence, as schematized in Fig. 2. A sound button played the plural [dal] when pressed, and upon completion, another sound button appeared. When pressed, the plural [do] was played, and the question “Which plural do you prefer?” appeared, with seven numbered buttons. The edges of the scale were labeled “the one on the left” and “the one on the right”. Once one of the seven buttons was pressed, a new screen with the next item appeared.

The order of presentation of the two plurals was randomized. After participants responded to the randomized list of 20 target items and fillers, they were asked to answer demographic questions (country of origin, current location, year of birth, sex, other languages spoken, suggestions).

3.1.4 Results

On average, speakers demonstrated an asymmetry in the treatment of monosyllables, preferring faithful plurals for monosyllabic items and alternating [o/ø] plurals for polysyllabic ones (3.5 vs. 4.3 on the 1–7 scale). In addition, they preferred faithful plurals with [ε] and alternating plurals with [a] (2.7 vs. 4.4); this comparison simply reflects the distribution based on vowel quality found in the lexicon. Both of these effects can be seen in Fig. 3, where error bars show 95 % confidence intervals. Figure 3 also shows an interaction: the monosyllabicity effect is much stronger for [a] than it is for [ε]. The difference between [j]-final and [l]-final items was overall rather small (3.6 vs. 4.0). The raw results are available at http://becker.phonologist.org/projects/FrenchPortuguese/.

To assess the statistical strength of these effects, a mixed-effects linear regression model was fitted using the lmer function from the lme4 package (Bates and Maechler 2013) in R, with rating of the alternation as the dependent variable.Footnote 7 The following predictors were used: monosyllabic, a binary predictor that contrasted monosyllables and polysyllables, vowel, a binary predictor that contrasted [a] with [ε], and consonant, a binary predictor that contrasted [l] with [j]. A fully crossed model is reported in Table 2.Footnote 8 The model confirms that alternations are significantly dispreferred with monosyllables (negative β) and significantly preferred with [a] relative to [ε], just as expected based on the lexicon (Sect. 2). A significant interaction shows that the effect of monosyllabicity is stronger with [a]. The difference between [l] and [j] came out as a weak trend, suggesting that the two consonants may be equally deletable.

3.1.5 Discussion

The experiment confirms that speakers have access to the lexical trends that we described in Sect. 2, and that they extend these trends from the real words of their language to novel words. We will show in Sect. 3.4 that the lexical predictions are strongly correlated with the experimental results. In particular, speakers prefer the alternation in polysyllabic words, keeping monosyllables relatively protected.

The lexical trends are projected from the lexicon even though the alternation is no longer productive or natural, and thus from the linguist’s perspective, there is no clear benefit to encoding the size-based faithfulness effect in the synchronic grammar. The discrete and grammatical treatment of this pattern is apparently irresistible to the learner, who generalizes over the lexicon using salient grammatical principles, even if those generalizations no longer apply to existing words over a natural alternation.

3.2 Experiment 2: Binary judgments

Experiment 1 established that French speakers prefer alternating plurals most in polysyllables that have [a] in their singular form. Two questions remain, however. Firstly, it is not clear what role the wellformedness of the singular might have on the choice of plural. Secondly, the use of a linear regression in the analysis of responses on a 1–7 scale is potentially problematic, because it assumes that participants are using the scale linearly (i.e., the distance between 1 and 2 reflects the same difference in acceptability as the distance between 2 and 3, etc.). To alleviate these concerns, the next experiment asked participants to rate the singular base before they judge the plural forms. Plural forms are presented for judgment in a binary yes-or-no task, to be analyzed with a logistic model. The materials and methods were kept exactly the same as in Experiment 1, with the sole difference being in the format of the individual trials.

3.2.1 Participants

The participants were recruited online using word of mouth, and volunteered their time and effort without compensation. Data was gathered from 52 people who completed the survey and self-identified as being born in France and being at least 18 years old; the rest was discarded. The server logs indicate that these 52 participants took on average 7 minutes to complete the experiment (range 3–27 minutes, median 5). The participants reported an average age of 32 (range 22–66, median 30). According to self-reports, 31 females and 21 males completed the experiment. 9 participants listed no other language or indicated that they are monolingual. Of those who listed other languages, 41 indicated some knowledge of English, 13 Spanish, 10 German, and smaller numbers of other languages.

3.2.2 Materials

The materials are identical to those of Experiment 1.

3.2.3 Procedure

Each item was first presented in the singular, in a frame sentence (as in Experiment 1), but with the singular written on a button. Pressing the button played the singular form and then a question was displayed, asking the participant to rate the item as a word of French on a scale of 1–5, as shown in Fig. 4. Once one of the 1–5 buttons was pressed, all buttons were disabled (turned gray and unpressable), and one of the plurals (either faithful or alternating, randomly chosen) was presented in a frame sentence containing a sound button. When pressed, the plural was played, and a question was displayed, asking the participant whether the plural was acceptable (yes or no). Once one of the two buttons was pressed, both were disabled, and the other plural was presented in the same way, again asking for a yes or no judgment of its acceptability. Pressing one of the final two buttons then moved the participant to the next item.

3.2.4 Results

As in Experiment 1, speakers accepted the alternating [o/ø] plurals with monosyllabic items significantly less than with polysyllabic items (40 % vs. 55 %). In addition, they accepted alternating plurals with [a] significantly more than plurals with [ε] (55 % vs. 29 %). Both of these effects can be seen in the bar plots in Fig. 5b. Figure 5b also shows an interaction: the monosyllabicity effect is much stronger for [a] than it is for [ε]. The difference between [j]-final and [l]-final items was overall rather small and insignificant (41 % vs. 50 %), and it was even smaller for the [a] items (59 % vs. 54 %).

In this experiment, speakers also rated the singulars on a scale of 1–5 before they judged the plural forms, seen in Fig. 5a. Overall, participants found the singulars to be of intermediate acceptability (3.0 on the 1–5 scale). Polysyllables were rated higher than monosyllables (3.2 vs. 2.7), and items with final [l] were rated higher than items with final [j] (3.0 vs. 2.7). Items with [ε] were rated slightly higher than items with [a] (3.0 vs. 2.9). This small difference between [ε] and [a] confirms that speakers successfully separated the rating of the singulars from the acceptability of the plural forms.

The acceptability of the faithful plurals mirrored the acceptability of the alternating plurals, so we do not report these here. The complete raw results are available at http://becker.phonologist.org/projects/FrenchPortuguese/.

The acceptability of the alternating plurals was modeled with a mixed-effects logistic regression, using the following predictors: base, or the acceptability of the singular base on the 1–5 scale, and the full crossing of the three predictors monosyllabic, vowel, and consonant, defined as in Experiment 1, and reported in Table 3.Footnote 9

The model in Table 3 shows that alternating plurals are highly significantly preferred in polysyllables and with [a], including a significant interaction. The difference between [l] and [j] did not reach significance at the .05 level. The correlations of base with the other predictors were very low (r<.14), suggesting that the observed effects of monosyllabicity and stem vowel go above and beyond the rating of the singular base. To confirm this point, we factored out the potential correlation of base with monosyllabic and vowel using residualization, i.e. taking the remaining predictive power of base once it did its best to predict monosyllabic and vowel; the residualized model is essentially identical to the one reported here.

3.2.5 Discussion

Overall, this experiment confirms and replicates the results of Experiment 1. Experiment 2 sharpens the interpretation of the results of Experiment 1 in two ways: Firstly, the singular base form was rated on its own, in addition to the plurals. The regression results suggest that the protection of monosyllables is statistically independent from the phonotactic wellformedness of the base. Secondly, the plurals were judged binarily, and thus could be modeled statistically using a logistic regression. This alleviates the potential concern about modeling a scalar rating using a linear regression. Importantly, Experiment 2 confirms the three strong effects found in Experiment 1: the difference between monosyllables and polysyllables, the difference between [a] and [ε], and their interaction. Neither experiment showed a significant effect of the final consonant. In short, the grammatically-mediated difference between monosyllables and polysyllables in nonce plural formation was robustly upheld with a wholly different rating methodology.

3.3 Experiment 3: No duration cues

Cross-linguistically, monosyllables are usually produced with segments that are phonetically longer than segments in polysyllables; this trend holds true in French generally, and it holds of the materials used in Experiments 1 and 2 specifically. Thus, a monosyllable such as [gnal] has a phonetically longer [al], while a disyllabic [guval] has a phonetically shorter [al]. As will be discussed in Sect. 6 below, longer segmental duration has been proposed as a source of protection from alternations, and according to this view, our materials in Experiments 1 and 2 provided participants with a phonetic cue that could be used in the judgments of the plural forms. To control for this effect, the current experiment uses artificially created auditory stimuli that maintain constant segmental duration; the experiment is otherwise identical to Experiment 2.

3.3.1 Participants

The participants were recruited online using word of mouth, and volunteered their time and effort without compensation. Data was gathered from 71 people who completed the survey and self-identified as being born in France and being at least 18 years old, discarding the rest. The server logs indicate that these 71 participants took on average 6 minutes to complete the experiment (range 3–18 minutes, median 5). The participants reported an average age of 35 (range 19–79, median 31). According to self-reports, 46 females and 22 males completed the experiment; 3 did not say. 5 participants listed no other language or indicated that they are monolingual. Of those who listed other languages, 62 indicated some knowledge of English, 25 Spanish, 14 German, and smaller numbers of other languages.

3.3.2 Materials

The same words were used as in Experiments 1 and 2. The auditory materials were not recorded by a native speaker, but rather generated by the mbrola text-to-speech system (Dutoit et al. 2006). Vowels were generated specifying a level pitch of 130 Hz, and a duration of 280 ms in final (stressed) position and 140 ms in non-final (unstressed) position. Consonants were specified with durations ranging from 80 ms to 160 ms, depending on their identity, but not on their position. The pitch and duration values were chosen to match the averages obtained from the naturally produced materials. The materials, then, had identical final syllables in, e.g. [zal] and [vøzal]. While the resulting materials sounded decidedly robotic, their segments were easily recognizable.

3.3.3 Procedure

The procedure is identical to that of Experiment 2.

3.3.4 Results

The results are overall similar to those in Experiment 2, with alternating plurals being accepted more with [a] than with [ε] (55 % vs. 17 %), with [l] more than with [j] (48 % vs. 32 %), and with polysyllables more than monosyllables (48 % vs. 39 %), as seen in Fig. 6b. Again, the ratings of the singulars show a preference for polysyllables over monosyllables (3.5 vs. 3.1 on the 1–5 scale), for [l] over [j] (3.4 vs. 3.1) and for [ε] slightly more than [a] (3.4 vs. 3.2), as seen in Fig. 6a.

The statistical analysis was performed as for Experiment 2, and reached similar results.Footnote 10 The final model in Table 4 shows that alternating plurals are significantly more acceptable when the rating of the base is higher and with the vowel [a]. More importantly, alternating plurals are accepted significantly more often in polysyllables than in monosyllables. There was no significant interaction of vowel and monosyllabicity.

As reported for Experiment 2 above (Sect. 3.2.4), we found that residualizing monosyllabic and vowel against base makes very little change to the model for Experiment 3, confirming that the preference for alternating plurals in polysyllables goes above and beyond the preference for polysyllabic singulars. We also fitted a regression model for the combined results of Experiment 2 and Experiment 3, with an added experiment factor; this combined model is only minimally different from the ones we report for each experiment individually, and no significant difference between the experiments was found.

3.4 Comparison of lexicon with experimental results

The three experiments confirm that speakers prefer alternating plurals when they are polysyllabic, and faithful plurals when they are monosyllabic. Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 also show that this preference goes above and beyond the higher ratings given to polysyllabic singular bases. Experiment 3 confirms that speakers prefer alternations in polysyllables even in the absence of segmental durational cues for monosyllabicity in the auditory materials they heard. This result shows that speakers have their own internal expectations about the distribution of plural alternations and that these expectations do not require support from the phonetic properties of the particular tokens presented to them.

All three experiments also showed a preference for alternations with [a] relative to [ε], as expected. There was a significant interaction of vowel and monosyllabicity in Experiments 1 and 2. In Experiment 3, a much larger estimate for the vowel effect left the interaction insignificant.

Comparing the predictions of our MaxEnt analysis in Sect. 2.3 to the participants’ responses per item, we see a strong and highly significant correlation, shown in the three panels of Fig. 7; the Spearman rank correlation coefficients are .78, .56, and .72 for the three experiments, all significant at p < .001. The lowest correlation, which is still rather strong, is found in the experiment with the smallest number of participants. Differently stated, there is a close match between the predictions of our lexicon-trained grammar and the observed treatment of nonce words. Our model by no means captures the entirety of the variance in the experimental results; in particular, there is a great deal of variance within each of the categories imposed by the MaxEnt model. It is thus possible that the prediction could be further improved perhaps using more fine-grained details regarding onset profiles.

The three experiments did not show a significant effect of final consonant. This result was somewhat unexpected given the predictions of our lexicon regression model and our MaxEnt analysis, and the general expectation that lexical trends usually extend to nonce words (Hayes and White 2013, contra Becker et al. 2011). We suggested that this “surfeit of the stimulus” case is due to the sonority hierarchy: if deletion of low-sonority segments is categorically blocked, speakers are biased to extend this trend upwards in the scale, not allowing liquids to be more deletable than glides. This effect can be incorporated into the MaxEnt analysis with a defeasible Bayesian prior that requires the weight of Max(glide) to be closer to zero. However, an additional explanation suggests itself: recall footnote 2, in which we mentioned the collinearity of final consonant with part-of-speech. Should learners opt for part-of-speech as the relevant generalization and completely ignore final consonant as a result, no effect of final consonant would be expected in our experiments. To test such a hypothesis, one would need to design an experiment explicitly contrasting l-final nouns and adjectives.

We conclude this section by focusing on the importance of the monosyllabic vs. polysyllabic effect in determining whether a noun will undergo the irregular plural alternation in French. In the next section, we turn to a parallel alternation in Portuguese, where the details of historical development are different. In particular, while the alternation is no longer natural in either language, the Portuguese alternation is very much alive, extending productively to polysyllabic words and loanwords.

4 A study of alternations in the Brazilian Portuguese lexicon

We now turn to another language where monosyllables are protected from alternations, despite the absence of a specific origin in terms of monosyllabicity in the historical development of the process. The laterals that gave rise to the [al/aj → o] alternation in French also play a role in Portuguese, where one finds a [w → j] alternation, e.g. [Ʒoɦ ˈnaw ∼ Ʒoɦˈnajs] ‘newspaper’. While the languages have a common Latin root, the changes occurred after the languages separated, and the details of historical development diverge. Nonetheless, the Portuguese pattern also falls along similar lines, whereby initial syllables are protected from the resulting irregular plural formation process for this specific group of nouns.

4.1 The Brazilian Portuguese regular plural

For most nouns in Portuguese, the plural is completely regular and predictable. In this language, nouns overwhelmingly end in a vowel, a glide, or one of the consonants [ɦ, s].Footnote 11 There are two plural suffixes available, in complementary distribution: [-s] after vowels and glides, otherwise [-is] after consonants. More specifically, the [-s] allomorph is observed after an oral vowel, [j], or any nasal vowel other than [̃ɐw̃], e.g. [ˈbaɦku ∼ ˈbaɦkus] ‘ship’, [eˈɾɔj ∼ eˈɾɔjs] ‘hero’, [ˈifẽ ∼ ˈifẽs] ‘hyphen’. The [-is] allomorph is regularly added to nouns that end in [ɦ, s], e.g. [ˈfloɦ ∼ ˈfloɾis] ‘flower’, [ˈvɔjs ∼ ˈvɔzis] ‘voice’. No suffix is added to nouns that already end in an unstressed vowel and [s] in the singular, e.g. [ˈlapis] ‘pencil’, [ˈõnibus] ‘bus’.

This leaves the nouns that end in [w] or in [̃ɐw̃]. The rest of this paper focuses on [w]; for the similar yet distinct patterning of [̃ɐw̃], see Huback (2007).

4.2 The plural of [w]-final nouns

Most of the [w]-final nouns of the language change the [w] to [j] in the plural, e.g. [aˈnεw ∼ aˈnεjs] ‘ring’, as in (8). We analyze this alternation pattern as taking the plural suffix /-is/, with concomitant fusion of the stem-final [w] and the suffix-initial [i].

When the stem-final [w] is preceded by [i], the [w] is lost completely, with the outcome depending on the position of stress. With final stress, the stem’s [w] is simply lost, as in [baˈhiw ∼ baˈhis] ‘barrel’. With penultimate stress, the stem’s preceding [i] changes to [e], as in [ˈfɔsiw ∼ ˈfɔsejs] ‘fossil’ (see also Huback 2007).

-

(8)

Brazilian Portuguese alternating, unfaithful plurals

shape

singular

plural

spelling

mono

ˈsaw

ˈsajs

〈sal〉

‘salt’

ˈmεw

ˈmεjs

〈mel〉

‘honey’

ˈpɾɔw

ˈpɾɔjs

〈prol〉

‘advantage’

iamb

Ʒoɦ.ˈnaw

Ʒoɦ.ˈnajs

〈jornal〉

‘newspaper’

a.ˈnεw

a.ˈnεjs

〈anel〉

‘ring’

ba.ˈhiw

ba.ˈhis

〈barril〉

‘barrel’

trochee

ˈni.vew

ˈni.vejs

〈nível〉

‘level’

ˈfɔ.siw

ˈfɔ.sejs

〈fóssil〉

‘fossil’

In contrast to nouns that take the unfaithful plural, other [w]-final nouns form their plural with simple suffixation of [s] and no further change, e.g. [ˈgow ∼ ˈgows] ‘goal’, as in (9). We analyze these as taking the plural suffix /-is/ with concomitant deletion of the suffixal [i].

-

(9)

Brazilian Portuguese non-alternating, faithful plurals

shape

singular

plural

spelling

mono

ˈpaw

ˈpaws

〈pau〉

‘stick’

ˈhεw

ˈhεws

〈réu〉

‘culprit’

ˈgow

ˈgows

〈gol〉

‘goal’

iamb

ka.ˈkaw

ka.ˈkaws

〈cacau〉

‘cocoa’

tɾo.ˈfεw

tɾo.ˈfεws

〈troféu〉

‘trophy’

mu.ˈzew

mu.ˈzews

〈museu〉

‘museum’

trochee

ˈaw.kow

ˈaw.kows

〈alcool〉

‘alcohol’

Historically, unfaithful plurals originate from nouns with a final lateral (Kolovrat 1923). Deletion of intervocalic laterals, which happened across the board in Galician-Portuguese (9th century), affected the plural, taking [ˈsal ∼ ˈsalis] ‘salt’ to [ˈsal ∼ ˈsais]. Much later (18th century), coda [l] vocalized to [w], yielding [ˈsaw ∼ ˈsais], with hiatus resolution creating the glide in [ˈsaw ∼ ˈsajs]. The faithful plurals are traced back to nouns that originally ended in [u] or [w], which simply took the plural [s], e.g. [muˈzew ∼ muˈzews] ‘museum’. Some nouns with faithful plurals had an intervocalic lateral that deleted in both singular and plural, e.g. [ˈpalo ∼ ˈpalos] ‘stick’ leading to [ˈpao ∼ ˈpaos] and from there via raising of unstressed mid vowels and hiatus resolution to the modern [ˈpaw ∼ ˈpaws].

With the vocalization of final laterals, the historical distinction between final [l] and final [w] can only be heard in the plural, as a distinction between alternation and non-alternation. This naturally leads to some fluctuation: some nouns that have normative faithful plurals have developed an innovative unfaithful plural, e.g. [deˈgraw] ‘step’ is often heard pluralized colloquially as [deˈgrajs]. Similar variation is seen in a number of nouns, e.g. [ʃa ˈpεw] ‘hat’, [tɾoˈfεw] ‘trophy’, as documented in Abaurre (1983), Huback (2007) and Gomes and Manoel (2010). These nouns are all polysyllabic with a lax stressed vowel; as we will see in Sect. 4.3, both polysyllabicity and lax vowels are conducive to unfaithful plurals. The innovation, then, is driven by extension of the existing trends in the lexicon. On the other hand, [ˈsaw] ‘salt’, which has the normative unfaithful plural [ˈsajs], has the innovative faithful plural [ˈsaws]. By hypothesis, initial syllable protection is the factor that causes the innovation of the faithful plural in this monosyllabic noun and others like it; again, we acknowledge that our account is equally consistent with protection of monosyllables rather than initial syllables.

These same trends also extend to loanwords, with monosyllables such as [ˈgow], from English ‘goal’, receiving faithful plurals, and polysyllables such as [kokeˈtεw], from English ‘cocktail’, receiving unfaithful plurals. A very small number of nouns, most of them monosyllabic, take the plural suffix [-is] with the stem-final [w] surfacing as [l], e.g. [ˈmaw ∼ ˈmalis] ‘evil’. In terms of our analysis, these plurals violate Ident(lateral). The pattern’s rarity suggests very limited productivity, and we thus left it out from our nonce word experiments. Our discussion and investigation is limited to those dialects that have fully merged the historic coda lateral with the labiovelar glide, making the plural only partially predictable. Dialects that maintain the coda lateral, as in some southern Brazilian dialects and most European Portuguese dialects, deserve separate attention in future work.

To summarize, the [w → j] change was created by a series of natural steps that resulted in a synchronically unnatural alternation. While the change happens in the environment of the overt plural suffix, it can hardly be described as assimilation, lenition, or any other such natural process. Thus, the plurals in both French and Portuguese represent synchronically unnatural patterns, which are nevertheless extended productively to nonce forms. While the productivity is mostly limited to experimental tasks in French, the Portuguese alternation is widely observed to be productive in everyday language use.

4.3 Trends in the irregular plurals

We collected the [w]-final nouns and adjectives and their plurals from two word lists.Footnote 12 We then presented them to three native speakers of Brazilian Portuguese, and kept only those items which were familiar and had a distinct plural form for at least one speaker. This left 387 w-final items: 32 monosyllables, 47 trochees (polysyllables with penultimate stress) and 308 iambs (polysyllables with final stress). The plural of each item was marked as either unfaithful, faithful, or variable (=50 % faithful). When our three speakers did not agree, we averaged their preferences. The dataset is available at http://becker.phonologist.org/projects/FrenchPortuguese/. Each item was coded for its number of syllables and position of stress, as well as the stressed and final vowel sounds.

The mosaic plot in Fig. 8 shows all 387 nouns in our list, plotted by prosodic shape. Only about 29 % of the monosyllables take unfaithful plurals, while 88 % of polysyllables do, i.e. monosyllables are protected from alternation. The rate of unfaithful plurals is lower for iambs (87 %) than it is for trochees (96 %).

Another factor that correlates with the choice of plural is the quality of the stem’s final vowel, particularly its tenseness, as seen in Fig. 8. Among the monosyllables, the lax vowels [a, ε, ɔ] are most conducive to alternating plurals, while the tense vowels [e, o, i, u] are most likely to have faithful plurals. While most of the evidence for the effect of vowel tenseness comes from the iambs, the effect is visible in the monosyllables as well.

A regression analysis with R’s glm function was used to determine the strength and reliability of the correlation between the properties of nouns and the kind of plural they take, and at the same time, make predictions about the treatment of novel nouns. The independent variable was a binary distinction between faithful and alternating plurals. Since 20 of the 387 items had an intermediate faithfulness level, a cutoff level of 50 % was chosen; other cutoff levels hardly made any difference.

The model includes a predictor for prosodic shape, coded as one factor that contrasts monosyllables and polysyllables, and one that contrasts iambs and trochees. We also included lax, a predictor that coded the laxness of final vowel of the root, contrasting the lax [a, ε, ɔ] with the tense [e, o, i, u].Footnote 13 This model has reasonably low collinearity (κ = 4.65). The interaction of lax and monosyllabicity caused separation and was left out,Footnote 14 but a likelihood ratio test shows that the interaction does not make a significant improvement to the model (\(\upchi^{2}(\mathit{1}) = 1.7\), p > .1).

The model in Table 5 confirms that polysyllables are significantly more likely to take alternating plurals than monosyllables, and trochees are significantly more likely to take alternating plurals than iambs. The lax vowels [a, ε, ɔ] are significantly more likely to take alternating plurals than the tense vowels [e, o, i, u].

Token frequency, as estimated by the SUBTLEX-BR corpus of Brazilian Portuguese, added no predictive value to the model, as reported in Tang et al. (2013). Model comparison revealed that while monosyllabicity made a significant improvement (\(\upchi^{2}(\mathit{1}) = 55.7\), p < .001) token frequency makes no significant improvement (\(\upchi^{2}(\mathit{1}) = .2\), p > .1). While token frequency is significant in a model that does not encode monosyllabicity, the role of token frequency is entirely subsumed by monosyllabicity.

4.4 Initial syllable faithfulness protects monosyllables

In this subsection, we provide an analysis of the asymmetry in plural formation between monosyllables and polysyllables in terms of initial syllable protection. As we discussed and implemented in Sect. 2.3 for French, a MaxEnt grammar combined with the UseListed approach allows established items to maintain a fixed plural, while novel items are free to vary according to grammatically-filtered trends.

Assuming that the plural suffix is underlyingly /-is/ for consonant-final stems, [w]-final nouns will form their plurals either by deleting the [i], as in /ˈgow + is/ → [ˈgows] ‘goals’ (violating Max), or by fusing the [w] and [i] to [j], as in /aˈnεw + is/ → [aˈnεjs] ‘rings’, violating Ident(back) and the anti-fusion constraint Uniformity.Footnote 15

The difference between monosyllables and polysyllables can be attributed to an initial syllable-specific version of Ident(back).Footnote 16 The analysis is outlined in the tableaux in (10)–(11) and largely parallels our analysis of French in Sect. 2.3. Here, Ident- (back) protects a monosyllable such as [ˈgow] ‘goal’ from changing its stem [w], but Max forces the alternation in a polysyllable such as [aˈnεw] ‘ring’.

(back) protects a monosyllable such as [ˈgow] ‘goal’ from changing its stem [w], but Max forces the alternation in a polysyllable such as [aˈnεw] ‘ring’.

-

(10)

Monosyllabic [ˈgow] protected from alternation

-

(11)

Polysyllabic [aˈnεw] fuses with the suffixal [i]

The fully faithful concatenation of the base and suffix is ungrammatical in Portuguese, e.g. *[ˈgowis], *[aˈnεwis]. We attribute this to a constraint against [w] in onset position, which holds without exception in the derived environment of the plural, and also fairly generally before high vowels throughout the language.

To capture the vowel laxness effect, the analysis requires a constraint that penalizes the alternating plural glides in the presence of tense vowels, i.e. *[+tense]j (named *ShallowDiph in (12)–(13) below). As discussed more fully in Nevins (2012), this constraint militates against shallow, poorly vertically dispersed diphthongs—those that combine a tense vowel with a high glide. In contrast, the steeper diphthongs [εj], [ɔj], [aj] are created more freely. This mirrors the typological preference for steep diphthongs that maximize height differences, cf. the ubiquity of [aj] and the rarity of [uj]. Here, we abstract away from the fact that this contrast between steep and shallow diphthongs is limited to the derived environment of plurals; Portuguese allows all possible vowel-glide combinations in monomorphemic words, e.g. [ˈboj] ‘bull’, [ˈhej] ‘king’.

As we did for French in Sect. 2.3, we fit a UseListed/MaxEnt grammar that was trained on the probability of the unfaithful plural in the lexicon, and predicts the likelihood or acceptability of the unfaithful plural in nonce words. As before, the MaxEnt Grammar Tool was used with its default settings (μ = 0, σ = 100,000). We used a total of five constraints in the analysis, four of which are shown with their assigned weights in (12)–(13). The fifth constraint, Ident(back), was assigned a weight of zero, and thus makes no numerical contribution to the analysis.

Faithful plurals incur a violation of Max, while alternating plurals incur violations within the two constraints of the Ident(back) family. In a polysyllable with a lax vowel like [pɾiˈzεw] (12), the alternation impacts the stressed syllable, but not the initial syllable. The created diphthong [εw] is steep and thus satisfies *ShallowDiph. In a monosyllable with a tense vowel (13), the alternation impacts the stressed syllable, which is also the initial syllable, and it creates the shallow diphthong [ej]. The equally shallow [ew] is not derived, and is thus grandfathered in (cf. McCarthy 2003). These three violations add up to lower the expected probability of the alternation.

-

(12)

MaxEnt prediction for an iamb with a stressed lax vowel

-

(13)

MaxEnt prediction for a monosyllable with a stressed tense vowel

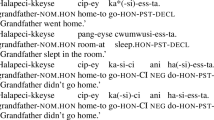

We note that our analysis assumes that the underlying representation of the singular is identical to its surface form, i.e. we do not encode the alternating or non-alternating plural patterning of [w]-final nouns in their underlying representation. As a result, the grammar can make gradient predictions based on prosodic and segmental factors that follow the lexical distribution of alternations, providing the information that is needed for the derivation of novel words. This marks a departure from the traditional structuralist analysis of Mattoso Câmara (1953), who assumes underlying laterals for alternating nouns. Our analysis (and purely-auditory experiments) do not rely on the orthographic cues to alternations (where alternations are often signaled with the letter 〈l〉). In fact, the innovative alternating plurals in nouns that are spelled without 〈l〉, such as 〈chapéu〉 with the plural [ʃaˈpεjs] ‘hats’, suggest that orthography does not determine whether alternations occur in natural usage. In the two experiments we discuss below, items were presented purely auditorily, thus removing any orthographic cues. To summarize, our analysis predicts that speakers monitor the distribution of faithful and unfaithful plurals in terms of monosyllabicity, vowel quality, and stress. In particular, the distinction between short words and long words is binary and discrete. In Sect. 5, we present speakers with a full crossing of prosodic shapes and vowel qualities and measure the effect of each factor.

5 Nonce testing the Brazilian Portuguese plural

The Portuguese lexicon provides strong evidence for the effect of monosyllabicity (which we take to be ultimately an initial syllable protection effect). The [w∼j] alternation is very much active, extending to nonce words and overtaking plurals of established lexical items, but never in monosyllables. Nevertheless, we sought to establish the productivity of the alternation experimentally, and in particular its sensitivity to monosyllabicity. The effect of vowel laxness is strong as well, and we will see that it is indeed extended to nonce words. The effect of stress is weaker in the lexicon than the effects of monosyllabicity and laxness, and we will see that it did not extend to nonce words; we discuss this matter in Sect. 5.3.

The two experiments we present here closely follow our methodology in Sect. 3, with judgments solicited on a 1–7 scale in Experiment 4, and binarily in Experiment 5.

5.1 Experiment 4: Scalar judgments

5.1.1 Participants

The participants were recruited online using word of mouth, and volunteered their time and effort without compensation. We gathered data from 181 people who completed the experiment and self-identified as being born in Brazil and being at least 18 years old; other data was discarded. The server logs indicate that these 181 participants took on average 6.4 minutes to complete the experiment (range 3–43 minutes, median 5). The participants reported an average age of 30 (range 18–71, median 27). According to self-reports, 95 females and 51 males completed the experiment; 35 did not specify.

When asked about the variety of Portuguese they speak, 97 participants listed São Paulo, 23 listed Rio de Janeiro, 21 Minas Gerais, 7 Porto Alegre, and a smaller number of other places in Brazil. 13 participants listed no other language or indicated that they are monolingual. Of those who listed other languages, 46 indicated some knowledge of Spanish, 43 French, 14 English, and a small number of other languages.

5.1.2 Materials

We created a total of 89 [w]-final nonce word items: 47 monosyllabic, 21 trochaic, and 21 iambic. The full list of items, with by-item results, is in Appendix C. In addition, we constructed 21 [s]-final items as fillers, 7 in each category of monosyllabic, trochaic, and iambic. As we did in French, the items’ onsets spanned a wide range of phonotactic wellformedness, from extremely common onsets like [d] and [f] to more uncommon ones like [bɾ] and [dɾ] (see discussion in Sect. 6).

The items were recorded by a female native speaker of Brazilian Portuguese in her twenties from Rio de Janeiro. She received basic phonetic training, and was unaware of the purpose of the task. The list included each noun in three forms: the singular, a faithful plural, and an unfaithful plural. The recording and processing was done as in Sect. 3.1.2.

5.1.3 Procedure

The experiment was run in Experigen (Becker and Levine 2012), as in Sect. 3.1.3. The web server executed a random selection of materials for each participant, choosing a total of 24 items: 15 target items (5 of each shape) and 9 fillers (3 of each shape). In addition, the experiment started with the sample item [ʃaˈpεw] ‘hat’, which is known to vary in the plural between the standard [ʃaˈpεws] and the colloquial [ʃaˈpεjs].

The items were presented in frame sentences that had a placeholder for a singular noun in a first phrase, followed by a second phrase with a placeholder for a plural noun. Upon pressing a first button, the singular and one of the plurals was played, and a second button appeared. When the second button was pressed, the singular and the other plural were played, and then seven numbered buttons appeared between the two play buttons, asking participants which plural was preferred by use of the scale. Pressing one of the seven buttons moved the participant to the next item. The order of plurals was randomized. The presentation and layout closely followed the procedure for Experiment 1 (see Fig. 2), except that the singulars were not presented orthographically at all.

After the participant responded to all 24 target items and fillers, they were asked to answer a few demographic questions, such as their country of origin, age, and so forth.

5.1.4 Results

On average, speakers preferred faithful plurals for monosyllabic items (3.9 on the 1–7 scale), and unfaithful plurals for polysyllabic ones, more strongly so for iambs (5.1) than for trochees (4.6), as seen in Fig. 9. The raw results are available at http://becker.phonologist.org/projects/FrenchPortuguese/.

As for the effect of the vowel that preceded the word-final [w], faithful plurals were chosen most often with the tense vowels [e, o, i, u] (4.3), and unfaithful plurals were chosen most often with the lax mid vowels [a, ε, ɔ] (4.8).

To assess the statistical strength of these effects, we used a linear mixed-effects model, with the rating of the alternation as the dependent variable. The predictors are those that were used in the lexicon model in Sect. 4.3. The fully crossed model, reported in Table 6,Footnote 17 enjoys low collinearity measures (κ = 2.16, vif ≤ 1.39).

The model in Table 6 shows that unfaithful, alternating plurals are highly significantly preferred in polysyllables and dispreferred in monosyllables. Among the polysyllables, there was no difference between iambs and trochees. Alternating plurals were also highly significantly preferred following the lax vowels [a, ε, ɔ], mirroring the distribution in the lexicon. The interaction of lax and monosyllabic was insignificant; the interaction of lax with iamb vs. trochee cannot be included in the model, because all trochees have a final tense vowel.

5.1.5 Discussion

The results confirm that Brazilian Portuguese speakers track the plurals of [w]-final nouns in terms of their prosodic shape and the stem’s final vowel. In particular, they prefer alternations in polysyllables and following lax vowels. The two effects are highly significant, and independent of each other (showing no significant interaction).

The generalization of these grammatical patterns to nonce items that were presented auditorily confirms that the phonological factors we identified are independent of the effects of history and orthography. While Huback (2007) makes a strong case for the effect of token frequency in plural formation for real words of Portuguese, Tang et al. (2013) present model comparisons based on a much larger corpus and demonstrate no advantage of token frequency as a predictor beyond syllable count. Naturally when it comes to experimental results, token frequency makes no prediction for nonce items, which are all equally infrequent and equally unfamiliar to the listener.

5.2 Experiment 5: Binary judgments

While the results of Experiment 4 were clear, we sought to further confirm them with a more refined methodology, as we did for French. We switch from a 1–7 scale to a binary choice, and concomitantly a logistic model for the analysis. Additionally, we ask speakers to rate the singular before the plurals are judged, to tease apart any effect of the singulars’ wellformedness.

5.2.1 Participants

The participants were recruited online using word of mouth, and volunteered their time and effort without compensation. We gathered data from 72 people who completed the survey and self-identified as being born in Brazil and being at least 18 years old; other data was discarded. The server logs indicate that these 72 participants took on average 10 minutes to complete the experiment (range 5–24 minutes, median 9). The participants reported an average age of 30 (range 19–62, median 28). According to self-reports, 35 females and 21 males completed the experiment; 16 did not specify.

When asked about the variety of Portuguese they speak, 18 participants listed São Paulo, 17 listed Rio de Janeiro, 15 Minas Gerais, 6 Rio Grande do Sul, and a smaller number of other places in Brazil. 9 participants listed no other language or indicated that they are monolingual. Of those who listed other languages, 39 indicated some knowledge of English, 14 French, 12 English, and a small number of other languages.

5.2.2 Materials and procedure

The experiment used the same structure and materials used in Experiment 4, with the only change being the presentation of each item. The presentation followed the same structure as Experiment 2, with the singular base rated first on a scale of 1–5, and then each plural judged as either acceptable or unacceptable with a binary choice. The materials were only presented auditorily, as in Experiment 4, and unlike Experiment 2.

5.2.3 Results

The results largely reflect the results of Experiment 4: alternating plurals were accepted least often with monosyllables (53 %), and significantly more often with trochees (67 %) and iambs (76 %) (Fig. 10). Alternating plurals were accepted most often with the lax vowels [a, ε, ɔ] (70 %) and least often with the tense vowels [e, o, i, u] (61 %). Looking only at polysyllables with a tense vowel in their final syllable, there is no significant difference between iambs (68 %) and trochees (67 %).

The statistical analysis was performed using a mixed-effects logistic regression model, with the acceptability of the unfaithful plural as the dependent variable. The predictors were the same ones used in Sect. 5.1.4, with the addition of base, the acceptability of the singular base on the 1–5 scale. The fully crossed model, reported in Table 7, enjoys low collinearity measures (κ = 2.28, vif ≤ 1.33).Footnote 18

Alternations were accepted significantly more often with polysyllables and when the stem’s last vowel was lax. The interaction was significant (the effect of laxness was stronger on polysyllables), unlike in Experiment 4. Alternating plurals were significantly more acceptable when the rating of the base was higher, as seen in French.

5.3 Comparison of lexicon with experimental results

The results of Experiment 4 and Experiment 5 both confirm that Brazilian Portuguese speakers protect monosyllabic stems from alternation, and that alternations are more acceptable when the stem’s final vowel is lax. The effect of the lax vowel is stronger in iambs than it is in monosyllables; this interaction came out significant in Experiment 5, and as a trend in the same direction in Experiment 4. In the lexicon, we were unable to estimate the interaction of laxness and monosyllabicity; this is because there is ample evidence for the effect of vowel laxness among the iambs, observable even in the innovative alternating plural 〈chapéis〉 [ʃaˈpεjs] ‘hats’ vs. the lack of such an innovation in 〈museus〉 [muˈzews] ‘museums’. On the other hand, the small number of monosyllables provides rather meager evidence for any laxness effect, leading to non-identifiability when attempting to estimate the interaction. It would seem that speakers are somewhat reluctant to fully extend the laxness effect from the iambs to the monosyllables, yielding the observed (somewhat weak) interaction.