Abstract

A long line of research takes some sign language loci to be the overt realization of variables. But as argued in Kuhn (2015), this analysis fails in ASL in two cases. (i) First, loci sometimes appear to be inherited through agreement rather than directly interpreted, in particular in those environments in which phi-features are known to remain uninterpreted (= ‘Kuhn’s Generalization’). (ii) Second, there are cases in which one and the same locus can refer to different individuals, in contradiction with the predictions of the standard theory. Kuhn concludes that sign language loci are an open class of features rather than of variables; and he provides a variable-free treatment of them, although without accounting for their deictic uses. While granting the correctness of Kuhn’s Generalization, we offer an alternative in which ASL loci are both features and variables: some loci (in particular deictic ones) obtain their value from an assignment function, and introduce presuppositions on the value of other (covert) variables; but loci are also subject to the same rules of agreement as phi-features, and they can thus remain uninterpreted in some other environments. We discuss their behavior both from the perspective of morpho-syntactic and of semantic theories of (apparent) feature agreement. Finally, we argue that in the tense domain spoken languages also have expressions that are featural while containing a variable element.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Old data are cited from earlier publications when relevant. New data were elicited using the ‘playback method’ (see e.g. Schlenker et al. 2013 and Schlenker 2014): repeated quantitative acceptability judgments and repeated inferential judgments were obtained from our consultant on separate days, on videos involving minimal paradigms.

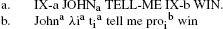

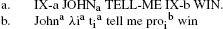

Glossing conventions are standard for sign language research, with IX-a encoding a pointing sign towards locus a, and with the subscript a on \(\mathit{BUSH}_{a}\) (as in (1a)) indicating that the expression BUSH was signed in locus a. CL stands for ‘classifier’, and in example (2), \(\mathit{CL}_{b}\)–\(\mathit{CL}_{a}\) refers to two index finger classifiers signed simultaneously, one with the right hand and the other with the left hand. Numbers following the examples (e.g. 4, 179 in (1)) are the references of the corresponding videos.

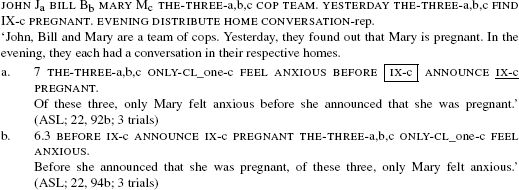

Two remarks should be added. First, we keep Kuhn’s transcription, but his ONLY-ONE corresponds to what we would transcribe here as ONLY-CL_one. We treat the latter expression as pronominal when it is signed in a locus that was established earlier, and thus had a prior reference; this decision should be revisited in future research. Second, in Kuhn’s video ONLY-ONE is in fact localized, and thus a more correct transcription would be: ONLY-ONEb in Kuhn’s notation, and ONLY-CL_one_b in ours; this is the reason we have added(b) as a subscript to ONLY-ONE in (3). (Thanks to J. Lamberton for discussion of this point, and to J. Kuhn for sharing his video.)

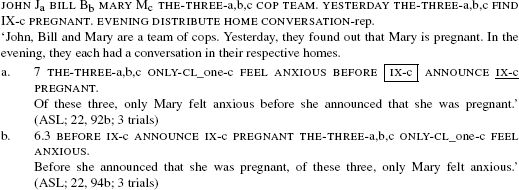

In fieldwork with a consultant that Kuhn also worked with, we elicited a different paradigm in which the context was strongly biased towards a bound-free interpretation, as shown in (ia). We believe that these further data confirm Kuhn’s insights.

-

(i)

When asked what one could infer about John, our informant noted on the first trial that (ia), but not (ib), lead to the inference that John told his family that Mary was pregnant. On the other two trials, he noted that (ia) but not (ib) weakly implied that John might have told his family about Mary’s pregnancy. These preliminary facts can be explained if (ia) has a reading on which

is bound and IX-c is free, and BEFORE triggers a (weak) factive presupposition, which is then projected according to the rule in (22) below. In (ib), the BEFORE-clause clause is not in the scope of ONLY-CL_one-c, hence no bound reading is available. These data could be theoretically helpful because the BEFORE-clause is presumably an island for the covert movement of pronouns. If so, we can reiterate Kuhn’s argument as follows: in (ia),

is bound and IX-c is free, and BEFORE triggers a (weak) factive presupposition, which is then projected according to the rule in (22) below. In (ib), the BEFORE-clause clause is not in the scope of ONLY-CL_one-c, hence no bound reading is available. These data could be theoretically helpful because the BEFORE-clause is presumably an island for the covert movement of pronouns. If so, we can reiterate Kuhn’s argument as follows: in (ia),  can get a bound reading, which shows that the temporal clause is in the scope of ONLY-CL_one-c. IX-c is trapped in the same island, and yet has a strict reading. But it couldn’t be that the very same variable c has a bound and a strict reading in this configuration. (Note that Kuhn’s example in (3) might include an island as well if ONLY-ONE has a relative clause as its sister.)

can get a bound reading, which shows that the temporal clause is in the scope of ONLY-CL_one-c. IX-c is trapped in the same island, and yet has a strict reading. But it couldn’t be that the very same variable c has a bound and a strict reading in this configuration. (Note that Kuhn’s example in (3) might include an island as well if ONLY-ONE has a relative clause as its sister.)-

(i)

The same issues arise in examples with ellipsis. But these arguably involve independent problems: in ellipsis resolution, it has been argued that a Logical Form with a bound variable representation can give rise to a strict reading in the elided clause (Fox 2000; Schlenker 2005). This is the reason the present discussion solely appeals to strict readings under only.

See Merchant (2014) for a recent discussion of the behavior of gender (and plural) features in ellipsis contexts in Modern Greek.

For von Stechow (2004), by contrast, now doesn’t itself carry the feature (as it is of type <i, <it, t≫ rather than i), but associates with a time variable that carries the relevant feature.

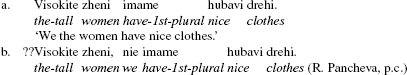

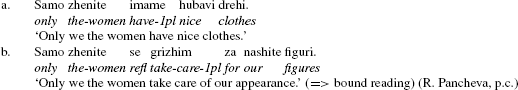

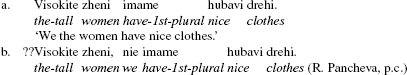

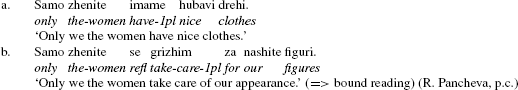

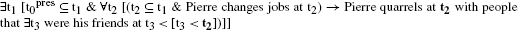

Note that Bulgarian definite descriptions might be similar to now in being able to ‘acquire’ a feature which is not overtly spelled out, but triggers agreement phenomena (this is also the behavior we attribute to the ASL expression for the tall man in (10) below). Thus in (ia), the plural description, which is unmarked for person, still triggers first person agreement on the verb. Furthermore, it is unlikely that this is due to a null pronoun co-occurring with a left-dislocated description, as left-dislocation is degraded with an overt pronoun, as shown by (ib).

-

(i)

Crucially, despite the fact that definite descriptions are morphologically unmarked for person, they can trigger deletion of first person plural features under only, as in (iia) (where verbal first person features must be deleted) and in (iib) (where both verbal and pronominal features must be deleted). One possibility is that the subject has the representation [the-women]1st plural, and that the subscripted feature triggers deletion of the same feature lower in the structure—just as the feature pres in (9b).

-

(ii)

-

(i)

An alternative research direction likens height specifications of loci to co-speech gestures rather than to features. Importantly, some co-speech gestures were argued to display precisely the behavior under discussion here in the scope of only, which suggests an alternative analysis of these data (Schlenker 2015a, 2015b).

The result is obtained by applying Jacobson’s z-rule to the meaning of left. Its base meaning is of type <e,t>, and is turned into a meaning of type ≪e, e>,t> after application of the z rule. The latter meaning is appropriate to compose with the meaning of you, which is a (partial) identity function over individuals, and hence of type <e,e>.

See Schlenker et al. (2013) for a discussion of the interaction between this rule and patterns of ‘locative shift’. Note that the distinction between first and non-first person is usually thought to be grammaticalized in ASL, but that the distinction between second and third person isn’t (Meier 1990). If so, second and third person all fall under the rule for deictic loci.

See Wechsler (2010) for a critique. Note also that the treatment of second person features in (13c) would, if applied to French, predict that the sentence Chacun de vous pense que tu es le plus intelligent (lit. Each of you-pl thinks that you-sg be-2sg the smartest) has a bound reading, akin to [Each of you] i thinks that you i are the smartest of the two. This is incorrect—tu definitely cannot be bound in this case.

The situation is complex. In (i), we need to allow my collaborator to carry a feminine feature in order to license a bound variable reading on which herself ranges over males.

-

(i)

Only my collaborator is proud of herself.

The rule that handles (9) and (10) can also achieve the desired result in this case. But then in (15) your four collaborators might also carry feminine features, which could conceivably be transmitted to the quantifier each of your four collaborators; if so, the features of herself would not have to be interpreted. Interestingly, the situation will be different in our sentence with bound iconic loci in (33), where one and the same quantifier binds two variables with contradictory iconic features, and hence couldn’t transmit them to both.

-

(i)

See Schlenker (2009), Appendix E for theoretical and empirical discussion; in a more general treatment, this rule would be stated within a focus-based semantics. Note also that the natural reading of (9) involves a slightly different lexical entry, akin to German erst rather than English only (von Stechow 2004).

This liberalized version of the semantic analysis and the morpho-syntactic analysis of features under only still make different predictions. The morpho-syntactic analysis predicts that it is solely under binding that features may be disregarded in the focus dimension. The liberalized semantic analysis predicts that binding is irrelevant. (Some of our more recent examples, pertaining to ‘locative shift’, might argue for the latter position.)

Schlenker (1999) speculates that the English present / past / pluperfect distinction is an abstract temporal counterpart of the proximate / obviative / further obviative distinction found in Algonquian; and he sketches a unified account of both. We do not know whether the remarks of this section apply to Algonquian.

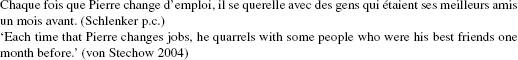

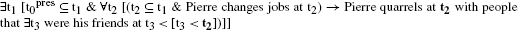

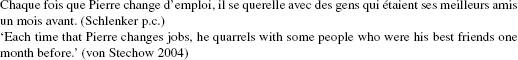

Stechow’s own example is in (i), and his Logical Form is in (ii).

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(i)

In general, standard constraints on variables should be added to account for Binding Theory (e.g. Büring 2005). In particular, an anonymous reviewer asks whether loci could be mismatched in examples such as (ia), with the Logical form in (ib)—with loci a and b both referring to John. We believe our system should be constrained to block these. But in this case independent considerations might do so:

-

(i)

In the Logical Form in (ib), i is a bound variable, and b is a free variable that presuppositionally constrains the value of i. As long as b denotes John, no presupposition failure arises. But (ib) is arguably ruled out by a general principled called Have Local Binding!, which mandates that salva veritate variables should be bound by the most local antecedents possible. Since b could be replaced with a locally bound variable a or i without changing the truth conditions, this representation is presumably ruled out.

-

(i)

References

Büring, Daniel. 2005. Binding theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fox, Danny. 2000. Economy and semantic interpretation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Heim, Irene. 1991. The first person: Class handouts. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Heim, Irene. 1994. Comments on Abusch’s theory of tense. In Ellipsis, tense and questions, ed. Hans Kamp, 143–170. University of Amsterdam.

Heim, Irene. 2005. Features on bound pronouns: semantics or syntax? Unpublished manuscript, MIT.

Heim, Irene. 2008. Features on bound pronouns. In Phi-theory: Phi-features across modules and interfaces, eds. Daniel Harbour, David Adger, and Susana Bejar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heim, Irene, and Angelika Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in Generative Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Jacobson, Pauline. 1999. Towards a variable-free semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy 22: 117–184.

Jacobson, Pauline. 2012. Direct compositionality and ‘uninterpretability’: The case of (sometimes) ‘uninterpretable’ features on pronouns. Journal of Semantics 29: 305–343.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2009. Making a pronoun: Fake indexicals as windows into the properties of pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 40(2): 187–237.

Kuhn, Jeremy. 2015. ASL loci: Variables or features? Journal of Semantics. doi:10.1093/jos/ffv005.

Liddell, Scott K. 2003. Grammar, Gesture and Meaning in American Sign Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lillo-Martin, Diane, and Edward S. Klima. 1990. Pointing out differences: ASL pronouns in syntactic theory. In Theoretical issues in sign language research, eds. Susan D. Fischer and Patricia Siple. Vol. 1 of Linguistics, 191–210. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Meier, Richard. 1990. Person deixis in American Sign Language. In Theoretical issues in sign language research, eds. Susan D. Fischer and Patricia Siple, 175–190. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Meier, Richard. 2012. Language and Modality. In Handbook of sign language linguistics, eds. Roland Pfau, Markus Steinbach, and Bencie Woll. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Merchant, Jason. 2014. Gender mismatches under nominal ellipsis. Lingua 151: 9–32.

Nouwen, Rick. 2003. Complement anaphora and interpretation. Journal of Semantics 20(1): 73–113.

Partee, Barbara 1973. Some structural analogies between tenses and pronouns in English. The Journal of Philosophy 70: 601–609.

Partee, Barbara. 1989. Binding implicit variables in quantified contexts. In Chicago Linguistic Society CLS, Vol. 25, 342–356. Reprinted in: Partee, Barbara H. 2004. Compositionality in formal semantics: selected papers by Barbara H. Partee. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 259–281.

Rooth, Mats. 1996. Focus. In Handbook of contemporary semantic theory, ed. Shalom Lappin, 271–297. Oxford: Blackwell.

Schlenker, Philippe. 1999. Propositional attitudes and indexicality: A cross-categorial approach. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2003. A plea for monsters. Linguistics and Philosophy 26: 29–120.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2005. Non-redundancy: Towards a semantic reinterpretation of binding theory. Natural Language Semantics 13(1): 1–92.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2009. Local contexts. Semantics and Pragmatics 2(3): 1–78. doi:10.3765/sp.2.3.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2011. Donkey anaphora: The view from sign language (ASL and LSF). Linguistics and Philosophy 34(4): 341–395.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2013. Temporal and modal anaphora in sign language (ASL). Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31(1): 207–234.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2014. Iconic Features. Natural Language Semantics 22(4): 299–356.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2015a. Sign language and the foundations of anaphora. Manuscript, Institut Jean-Nicod and New York University.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2015b. Gestural presuppositions (squib). Snippets 30 (2015). doi:10.7358/smp-2015-029-schl.

Schlenker, Philippe, Jonathan Lamberton, and Mirko Santoro. 2013. Iconic variables. Linguistics and Philosophy 36(2): 91–149.

Spathas, Giorgos. 2007. Interpreting gender features on bound pronouns. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS 38)

Stechow, Arnim von. 2004. Binding by verbs: Tense, person and mood under attitudes. In The syntax and semantics of the left periphery, eds. Horst Lohnstein and Susanne Trissler, 431–488. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Wechsler, Stephen. 2010. What “you” and “I” mean to each other: Person marking, self-ascription, and theory of mind. Language 86(2): 332–365.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Jeremy Kuhn for theoretical and empirical discussions (both of English and of ASL data); to Benjamin Spector for ongoing discussions; and to three anonymous NLLT referees, as well as to Editor Jason Merchant, for helpful suggestions and criticisms. Special thanks to Roumi Pancheva for providing the Bulgarian examples and judgments reported in fn. 7.

An earlier (and different) version of this paper appeared as a ‘working paper’ in MIT Working Papers in Linguistics #71: The Art and Craft of Semantics, Vol. 2, Eds. Luka Crnic and Uli Sauerland, 2014.

The research leading to these results received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007–2013)/ERC Grant Agreement N°324115–FRONTSEM (PI: Schlenker). Research was conducted at Institut d’Etudes Cognitives, Ecole Normale Supérieure—PSL Research University. Institut d’Etudes Cognitives is supported by grants ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL∗ and ANR-10-LABX-0087 IEC.

ASL consultant: Jonathan Lamberton. Special thanks to Jonathan Lamberton, who provided exceptionally fine-grained data throughout this research; his contribution as a consultant was considerable. He also corrected and provided expert advice on all transcriptions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Complement set anaphora and loci as variables

Appendix: Complement set anaphora and loci as variables

We briefly discuss below an interpretive property of plural loci that can be analyzed within a variable-full system, but might not be trivial to handle in a pure agreement-based analysis. Plural loci are realized in ASL (and LSF) as semi-circular areas, which closely correspond to plural variables. Now in some cases one plural locus a can be embedded within a larger plural locus ab, with the result that a ‘complement locus’ b suddenly pops into existence, and denotes the complement of the denotation of a within the denotation of ab. An ‘iconic’ analysis was offered for this phenomenon in Schlenker et al. (2013), but it hinged rather crucially on a treatment of plural loci as variables that have a denotation.

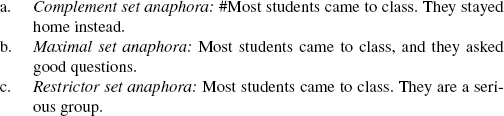

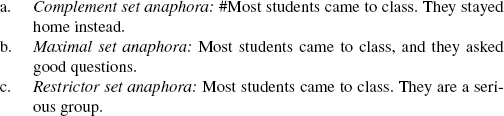

To introduce the issue, we start with the English sentence Most students came to class. Recent research has argued that it makes available two discourse referents for further anaphoric uptake: one corresponding to the maximal set of students, as illustrated in (41b) (‘maximal set anaphora’); and one for the entire set of students, as illustrated in (41c) (‘restrictor set anaphora’).

-

(41)

By contrast, no discourse referent is made available for the set of students that didn’t come to class (‘complement set anaphora’, as this is the complement of the maximal set within the restrictor set); this is what explains the deviance of (41a) (see Nouwen 2003 and Schlenker et al. 2013 for further discussion of apparent counterexamples).

On the basis of ASL and LSF data, Schlenker et al. (2013) made two main observations.

Observation 1

When a default plural locus is used in ASL, data similar to (41) can be replicated—e.g. complement set anaphora with most is quite degraded.

Observation 2

When embedded loci are used, the effect is circumvented: one large locus (written as ab, but signed as a single circular locus) denotes the set of all students; a sub-locus (=a) denotes the set of students who came; and a complement locus (=b) thereby becomes available, denoting the set of students who didn’t come, as illustrated in (42) and (43).

-

(42)

7 poss-1 student ix-arc-ab most ix-arc-a a-came class. ix-arc-a a-ask-1 good question.

‘Most of my students came to class. They asked me good questions.’ (ASL; 8, 196)

-

(43)

Schlenker et al. (2013) account for Observation 1 and Observation 2 by assuming that (i) Nouwen is right that in English, as well as ASL and LSF, the grammar fails to make available a discourse referent for the complement set, i.e. the set of students who didn’t come; but (ii) the mapping between plural loci and mereological sums preserves relations of inclusion and complementation, which in (42a) makes available the locus b.

The main assumptions are that (A1) the set of loci is closed with respect to relative complementation: if a is a sublocus of b, then (b-a) is a locus as well; and (A2) assignment functions are constrained to respect inclusion and relative complementation: if a is a sublocus of b, the denotation of a is a subpart of the denotation of b, and (b-a) denotes the expected complement set. In (42a), where embedded loci are used, we can make the following reasoning:

-

Since a is a proper sublocus of a large locus ab, we can infer (by assumption A1) that (ab-a) (i.e. b) is a locus as well.

-

By assumption A2, we can also infer that s(a) ⊂ s(ab) and that s(b) = s(ab)-s(a).

In this way, complement set anaphora becomes available because ASL and LSF can rely on an iconic property which is inapplicable in English. For present purposes, what matters is that the locus b in (42a) and (43) is not inherited by way of agreement, since it is not introduced by anything. From a variable-full perspective, the existence of this locus is inferred by a closure condition on the set of loci, and its denotation is inferred by an iconic rule. But the latter makes crucial reference to the fact that loci have denotations. It is not trivial to see how this result could be replicated in a variable-free analysis in which loci don’t have a denotation to begin with. One possibility is that the complement set locus should be treated as being deictic (which is the one case in which the variable-free analysis has an analogue of variable denotations). This might force a view in which complement set loci are handled in a diagrammatic-like fashion, with co-speech gestures/diagrams incorporated into signs—something that would require a more detailed investigation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schlenker, P. Featural variables. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 34, 1067–1088 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9323-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9323-7

is bound and IX-c is free, and BEFORE triggers a (weak) factive presupposition, which is then projected according to the rule in (22) below. In (ib), the BEFORE-clause clause is not in the scope of ONLY-CL_one-c, hence no bound reading is available. These data could be theoretically helpful because the BEFORE-clause is presumably an island for the covert movement of pronouns. If so, we can reiterate Kuhn’s argument as follows: in (ia),

is bound and IX-c is free, and BEFORE triggers a (weak) factive presupposition, which is then projected according to the rule in (22) below. In (ib), the BEFORE-clause clause is not in the scope of ONLY-CL_one-c, hence no bound reading is available. These data could be theoretically helpful because the BEFORE-clause is presumably an island for the covert movement of pronouns. If so, we can reiterate Kuhn’s argument as follows: in (ia),  can get a bound reading, which shows that the temporal clause is in the scope of ONLY-CL_one-c. IX-c is trapped in the same island, and yet has a strict reading. But it couldn’t be that the very same variable c has a bound and a strict reading in this configuration. (Note that Kuhn’s example in (3) might include an island as well if ONLY-ONE has a relative clause as its sister.)

can get a bound reading, which shows that the temporal clause is in the scope of ONLY-CL_one-c. IX-c is trapped in the same island, and yet has a strict reading. But it couldn’t be that the very same variable c has a bound and a strict reading in this configuration. (Note that Kuhn’s example in (3) might include an island as well if ONLY-ONE has a relative clause as its sister.)