Abstract

Surface morphology is notoriously inconsistent both language-internally and cross-linguistically in providing any kind of reliable reflex of covert syntactic features. This paper addresses the difficult question of how the acquirer is able to deduce the presence/absence of particular (covert) features on functional items, here features of finiteness, given that they cannot rely on morphology. The paper has the following goals. First, it makes a fairly narrow empirical claim, specifically, that Telugu does not have PRO in its lexicon (and therefore does not have Control). Clausal subjects can easily be accounted for by pro, needed in Telugu for independent reasons. Second, because PRO/Control is so closely associated with finiteness, the paper explores whether there are other elements in Telugu that correspond to those usually associated with finiteness cross-linguistically. Third, the paper argues that, although traditional aspects of finiteness seem to be lacking, a more coherent notion of finiteness, based upon requirements of temporal and logophoric anchoring, should be adopted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For the moment, I will ignore the difference between a PRO/Control analysis and a Copy Theory of Control analysis, from here on referred to as Movement/Control, and refer generally to ‘PRO/Control’.

Either form may have a tense component in Telugu, therefore the only truly distinguishing factor is agreement.

The one exception to this is clauses marked with the quotative particle ani. The quotative marker causes its own content to be opaque to matrix clause syntax, where, as in English, nonsense words, humming, and other behaviors not regulated by the grammar may be included without inducing ungrammaticality.

Unless otherwise indicated, all Telugu examples are from my own work with native speakers, all of whom speak the Coastal dialect with the exception of one Telangana speaker. Note that the Rayalasima dialect of southern Andhra, where it borders on Tamil Nadu, is not represented. Dialect variation in the phonology has been largely ignored in favor of standard spelling as it does not seem relevant to this topic. I would particularly like to thank the consultants who contributed most heavily to the current project and who have been so generous and flexible with their time. They are Vishnu Merapala, SaiSundar Reddy, Siddhartha Kattoju, Venkata Lakshmi Mantha, Krishna Palepu and Indrani Gorti. Examples taken from Telugu reference materials are cited as such. In these cases, ‘LL’ indicates Lisker (1963), ‘K’ indicates Krishnamurti and Gwynn (1985). All Telugu and Tamil examples not my own are cited verbatim. PERM (Permissive) and OBLIG (Obligative) are the only non-standard glosses. Naturally, all errors are my own.

The overt conjunction, mariju, is not typically used in colloquial, spoken Telugu. Its presence or absence here does not affect the grammaticality status of the string. I have glossed the accusative object ACC even without its accusative suffix just to be clear. Inanimates need not be overtly marked with accusative.

Telugu CPs, TPs, and v/VPs are all strictly head-final.

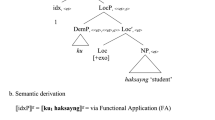

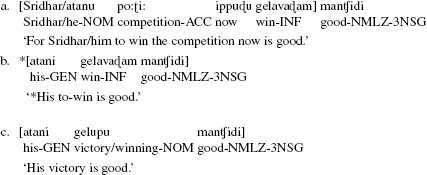

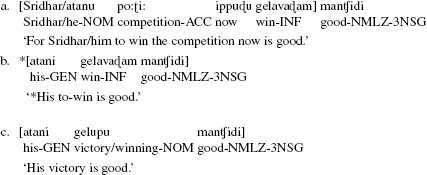

There is no general agreement in Telugu reference materials on these terms or even on the description of the behavior of the various forms. Both Sastri and Janert (1985) and Krishnamurti and Gwynn (1985) use the term ‘infinitive’ for the compounding form of the verb root, which cannot appear unsuffixed and is in no way equivalent to the standard use of ‘infinitive’, which normally refers to a free form bearing no agreement, no aspect, and, most frequently, no tense. Bossé and Bossé (1991) refer to the same form in -aɖam as an infinitive. That the categorical status of this form is verbal as opposed to nominal may be seen by comparing the examples below.

Complement DPs and adverbials may freely be part of the infinitive clause as in (a). The adverb ippuɖu ‘now’ may only be interpreted as a modifier of ‘win the competition’ and not as a modifier of the matrix clause. Possessive and deictic modification of an infinitive is ungrammatical in Telugu, as in (b) (deictic not shown). Note the grammaticality of the English equivalent, though—‘His winning is good’. A noun, formed from the verb root, shows quite the opposite behavior as in (c). The behavior of the -aɖam form suggests that ‘infinitive’ is the better characterization and I adopt that here.

His choice of adjuncts is based on his claim that these two are the only Conjunctive Participles (CNP’s) in Telugu, citing Krishnamurti and Gwynn (1985). Not only do Krishnamurti and Gwynn (1985) cite four Conjunctive Participles (plus the negative form of each) but Haddad himself retracts his claim regarding disjoint subjects in a footnote. A full discussion of these and other problems with Haddad’s data and analysis are given in Kissock (2011).

In order to distinguish the positions of the subjects, Haddad has used a dative subject predicate for the embedded clause. The literal translation of the embedded clause is ‘hunger came/having-come to Kumar/to him’.

Given this, any claims of Forward, Backward and Copy Control are premature, at best.

This question is relevant whether or not one adopts the Null Case analysis for PRO—both lack of any Case and Null Case are equally ineffective when a DP requires some non-Null Case.

As Sundaresan and McFadden point out later in their paper, an overt co-referential subject is possible in these cases in the embedded clause.

Presence or absence of -ki (discussed earlier in Sect. 2) has no effect on the embedded subjects in terms of Case assignment (always nominative), co-reference/disjunction, or overt/covertness.

The internal sandhi between the infinitive and the dative suffix follows the same pattern as is found in Sanskrit and Hindi loanwords in [-am] e.g., ‘book’ pustakam (nom) pustaka:nni (acc) pustaka:niki (dat).

Native speakers find the (linearly) second subject somewhat redundant sounding. When given contrastive focus, such as with the two pronoun forms ending in -e:, the emphatic marker, the redundancy disappears.

We expect to see verbs like ‘begin’ pattern with the ‘try’ type for these same reasons.

The notion of ‘dative subject’ is widely assumed for Dravidian languages, however the Telugu data has not been analyzed in a contemporary syntactic framework, as far as I know. More detailed discussion of the matter is certainly necessary but is precluded here for reasons of time and immediate relevance. Furthermore, an anonymous reviewer pointed out that the presence of raising to subject in Telugu, if there was such a phenomenon, could have an impact. However, Telugu has no raising to subject cases, no expletives, and no ECM cases, to my knowledge.

Sundaresan and McFadden (2010) provided an earlier example showing that veɳɖ- is transitive in simplex clauses, taking just a DP. veɳɖ- happens to be a dative subject verb in Tamil. Sundaresan and McFadden point out that, in Tamil, dative subjects in the embedded infinitive clause also occur, noting that this suggests that overt Case on the embedded subject is determined by properties of the embedded clause itself rather than the matrix clause.

There is a verb ko:ru ‘desire/request’ but it is more limited/specialized in its semantics and is far less common. It behaves no differently than the other verbs we are looking at, in any event.

Example (29) is a slightly modified version of Viswanatham’s (2007) example (b) [224] navvutu: ma:ʈla:ɖite: a:meku ko:pam vastundi with some additions to show the full clausal structure of the embedded clauses.

Both atani and tana are used to translate ‘his’ in this case, the latter being the root without the deixis prefix. The fact that tana (Nominative tanu) is often referred to as the reflexive form is misleading, as its distribution is that of a pronoun. (See Kissock 1995 for a complete discussion of reflexivization in Telugu). I give only the deictic pronominal form in the subsequent example simply to avoid multiplication of parentheses.

Vijayasri (2003) includes a brief and inconclusive discussion of Weak Crossover, showing the opposite of the standard WCO effect.

Some native speakers feel that the absence of both overt subjects simultaneously is marginal but it appears to be based on pragmatic concerns about picking out a referent for the subject related to the discourse factors governing pro-drop.

See Biezma (2011) and a number of references within for independent discussion and support of such a claim.

It turns out that Tamil can, as well. Sundaresan p.c.

I thank the reviewer who suggested both this and the following strict/sloppy interpretation as additional diagnostics.

Note that, in this particular case, the co-indices indicate real world reference as opposed to a reference assigned by the speaker.

These judgements are quite robust, with speakers noting the ambiguity immediately and without any prompting for ‘want’. With the appropriate contextual setting, even ‘try’—noted earlier as already much more difficult semantically with disjoint subjects—has both readings. Crucially, speakers’ behavior with ‘try’ was identical whether or not the subject of the lower clause was an overt pronoun or null.

Note, however, that there has been a very strong general assumption in the scholarly literature that a language will have PRO/Control. This may be partially responsible for the extremely wide range of phenomena for which proposals of PRO/Control have been made.

Specifically, the cost of the movement itself (Hornstein 1999). However, it should be noted that Movement/Control is not inconsistent with some of the features noted above.

If we consider any of these clauses in a historical perspective, they are essentially perfect from the standpoint of the Projection Principle and the Theta Criterion. Had Telugu and its Dravidian relatives been the initial object of study instead of English and a few other Indo-European languages, it seems likely that the theory would have taken a rather different trajectory.

From GB through Minimalism, structural Nominative CASE has been associated with Tense-Agr/‘finite’ properties of T. Recently, it has been suggested that these features are inherited from C (Chomsky 2007 and citations therein). This connection between T and ‘finiteness’ is not the only approach to Case in the literature, of course, just the approach that is part of the theoretical framework of this particular paper.

Of course, we must use syntactic arguments to determine abstract features, though the risk of circularity is extremely high and must be guarded against.

appuɖu is the complementizer.

This is just one of a number of contradictory cases (see Huang 1984 for Chinese among others). In fact, the notion of connecting overt tense and agreement to pro-drop seems to be due to a misunderstanding of whether we are modelling the processing ability of the ‘listener’ or the linguistic computational knowledge of the ‘speaker’. The syntax cannot constrain or regulate pro-drop based on (phonological) information it does not have.

By our own earlier argument, it is perfectly possible that these surface ‘non-finite’ forms have underlying tense and/or agreement features. If we take those features to be indicative of ‘finiteness’ and assume that the features are present here, we have, of course, an unremarkable independent clause.

Chomsky (2007) noted that C never seems to manifest Tense in any language, though it does occasionally manifest phi features. Telugu may be an exception to reflexes of Tense on C, however. Several of the NoAgree forms that show tense appear to show it in exactly the position of a complementizer. Exploration of this possibility would take us too far afield here but merits further work. For a comprehensive discussion of these and related issues, see Epstein et al. (2011, 2013).

External sandhi between final and initial vowels produces the form tina:lani from tina:li and ani.

I take the use of ‘Fin’ in ‘FinP’ to have approximately the same status as the use of ‘C’ of ‘CP.’ That is, the label is only a reflection of its historical source within the field and in no way determinative as to the interpretation of the function of the domain, just as ‘Complementizer’ is no longer an accurate description of many roles of ‘C’-elements.

The presence of such features is a necessary but not sufficient condition for utterance independence since such features occur in dependent utterances as well. Bianchi (2003) touches upon one way of instantiating this difference by proposing both ‘Internal’ and ‘External’ Logophoric Centres.

I am adopting the general notion here rather than any particular theoretic implementation of the relationship, something that would require much more time and consideration than space allows.

It is, of course, perfectly possible to have a sequence of independent utterances, in which case there is no violation of the conjunction constraint. The two key differences between conjoined utterances and sequential utterances are in the absence/presence of a pause and the different intonational patterns (no sentence-final vs. sentence-final).

Additional evidence for this comes from the fact that matrix clauses coordinated with ‘or’ are grammatical in Telugu. Presumably this reflects the effects of the disjunctive nature of ‘or’ on the number of Speech Events entertained. I am currently exploring these distinctions.

Subordinate clauses are already treated separately as being anchored internally to the matrix clause rather than externally (see Bianchi 2003).

References

Adger, David. 2007. Three domains of finiteness: A minimalist perspective. In Finiteness: Theoretical and empirical foundations, ed. Irina Nikolaeva, 23–58. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Amritavalli, R., and K. A. Jayaseelan. 2007. Finiteness and negation in Dravidian. In Oxford handbook of comparative syntax, eds. G. Cinque and R. Kayne, 178–220. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bianchi, Valentina. 2003. On finiteness as logophoric anchoring. In Temps et point de vue/tense and point of view, eds. Jacqueline Guéron and Liliane Tasmovski, 213–246. Paris: Université Paris X.

Biezma, Maria. 2011. Multiple focus strategies in pro-drop languages: Evidence from ellipsis. Ms., Carleton University.

Bošković, Zeljko. 1997. The syntax of nonfinite complementation: An economy approach. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bossé, Deena, and Olivier Bossé. 1991. Manuel de télougou. Paris: Harmattan.

Bouchard, Denis. 1985. Pro, pronominal or anaphor. Linguistic Inquiry 16 (3): 471–477.

Chomsky, Noam. 1982. Some concepts and consequences of the theory of government and binding. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2007. Approaching UG from below. In Interfaces + recursion = language?, eds. U. Sauerland and H. M. Gärtner, 1–29. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Dukes, Michael P. 1996. On the nonexistence of anaphors and pronominals in Tongan. PhD diss, University of California, Los Angeles.

Enç, Murvet. 1987. Anchoring conditions for tense. Linguistic Inquiry 18: 633–657.

Epstein, Samuel D., Hisatsugu Kitahara, and Daniel Seely. 2011. Derivations. In Oxford handbook of linguistic minimalism, ed. Cedric Boeckx. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Epstein, Samuel D., Miki Obata, Hisatsugu Kitahara, and Daniel Seely. 2013. Economy of derivation and representation. In The Cambridge handbook of generative syntax, ed. Marcel den Dikken. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gair, James W. 2005. Some aspects of finiteness and control in Sinhala. In The yearbook of South Asian languages and linguistics.

Ghomeshi, Jila. 2001. Control and thematic agreement. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 46 (1/2): 9–40.

Haddad, Youssef. 2009. Copy control in Telugu. Journal of Linguistics 45 (1): 69–109.

Higginbotham, James. 2000. On events in linguistic semantics. In Speaking of events, eds. James Higginbotham, Fabio Pianesi, and Achille C. Varzi, 49–79. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hornstein, Norbert. 1999. Movement and control. Linguistic Inquiry 30 (1): 69–96.

Huang, C. T. James. 1984. On the distribution and reference of empty pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 15: 531–574.

Jackendoff, Ray, and Peter W. Culicover. 2003. The semantic basis of control in English. Language 79 (3): 517–556.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2004. The serial verb construction in Malayalam. In Clause structure in South Asian languages, eds. Veneeta Dayal and Anoop Mahajan, 67–91. Boston: Kluwer Academic.

Karimi, Simin. 2008. Raising and control in Persian. Aspects of Iranian linguistics.

Kissock, Madelyn J. 1995. Reflexive-middle constructions and verb raising in Telugu. PhD diss, Harvard University.

Kissock, Madelyn J. 2011. Against copy control in Telugu. Workshop on South Asian Syntax and Semantics, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, March 19–20, 2011.

Krishnamurti, Bh., and J. P. L. Gwynn. 1985. A grammar of modern Telugu. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Landau, Idan. 2004. The scale of finiteness and the calculus of control. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 22 (4): 811–877.

Lee, Kum Y. 2009. Finite control in Korean. PhD diss, University of Iowa.

Lisker, Leigh. 1963. Introduction to spoken Telugu. New York: American Council of Learned Societies.

Massam, Diane. 1995. Clause structure and case in Niuean. Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics 14.

Pires, Acrisio. 2007. The derivation of clausal gerunds. Syntax 10 (2): 165–203.

Platzack, Christer. 1995. The loss of verb second in English and French. In Clause structure and language change, eds. Adrian Battye and Ian G. Roberts, 200–226. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Polinsky, Maria, and Eric Potsdam. 2006. Expanding the scope of control and raising. Syntax 9 (2): 171–192.

Raposo, Eduardo. 1987. Case theory and Infl-to-Comp: The inflected infinitive in European Portuguese. Linguistic Inquiry 18 (1): 85–109.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar: Handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Safir, Ken, and Osvaldo Jaeggli. 1989. The null subject parameter. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Sastri, Koradeva M., and Klaus L. Janert. 1985. Descriptive grammar and handbook of modern Telugu: With key. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner.

Schlenker, Phillippe. 2003. A plea for monsters. Linguistics and Philosophy 26 (1): 29–120.

Shlonsky, Ur. 1997. Clause structure and word order in Hebrew and Arabic: An essay in comparative semitic syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sigurðsson, Halldór Ármann. 1991. Icelandic case-marked PRO and the licensing of lexical arguments. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 9 (2): 327–363.

Sigurðsson, Halldór Ármann. 2004. The syntax of person, tense, and speech features. Italian Journal of Linguistics 16: 219–251.

Sundaresan, Sandhya, and Thomas McFadden. 2010. Subject distribution and finiteness in Tamil and other languages: Selection vs. case. Journal of South Asian Linguistics 2 (1).

Szabolcsi, Anna. 2009. Overt nominative subjects in infinitival complements in Hungarian. Approaches to Hungarian 11.

Usha Devi, A. 1988. Are complex sentences really complex? Opilaste 14: 55–63.

Vijayasri, N. 2003. Anaphora in Telugu. Tirupati: Sri Venkateswara University.

Viswanatham, K. 2007. Structure of Telugu phrases. Mysuru: Central Institute of Indian Languages.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank participants of the Finiteness in South Asian Languages conference, Tromsø, June 9–10, 2011 for their many topical presentations and helpful comments and suggestions, especially Sandhya Sundaresan, Thomas McFadden, and Gillian Ramchand. I would also like to thank the audience of the Workshop on South Asian Syntax & Semantics, UMass Amherst, March 19–20, 2011 for input on an earlier paper on a related topic. Several colleagues were kind enough to read earlier drafts and offer helpful suggestions and I would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful contributions. Finally, without the help of many Telugu speakers, I could not have accomplished this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kissock, M.J. Evidence for ‘finiteness’ in Telugu. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 32, 29–58 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9214-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9214-8