Abstract

This paper looks in detail at the Classical Armenian nominal declension. I highlight several generalizations that can be read off the surface paradigms, including restrictions on syncretism, fusional vs. agglutinative expression of categories and the emergence of unexpected thematic vowels. Subsequently, I explain these generalizations within the framework of Nanosyntax (Starke 2009, 2011).

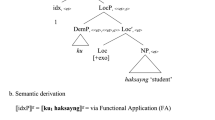

The defining features of the account are fine-grained syntactic representation (a single feature per syntactic terminal) and phrasal spell-out. I argue that these two tools allow us to replace a separate level of morphological (paradigm specific) structure by a syntactic tree.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Examples from Krause and Slocum (no date).

To put the idea in a context: within Cartography (Cinque and Rizzi 2010), it is generally agreed that each feature is hosted by a separate head. A related idea is presented in Kayne (2005). Starke (2009, 2011) develops these ideas in a specific framework, Nanosyntax, whose research program I follow closely.

Had there been two positions in syntax, a separate rule (presumably Fusion) would be needed to handle those cases where only a single marker appears.

The phrase “non-accidental” in (4) is intended to exclude two sources of homophony: (i) phonological conflation, whereby two distinct underlying forms end up homophonous due to a regular phonological process, and (ii) accidental homophony. Accidental homophony plays no role in this paper; however, one instance of homophony will be analyzed as an example of phonological conflation in the sense described above (see Sect. 10.3).

dat–loc syncretism across a distinct gen is attested in the pronominal declension (e.g., mez/jez ‘we, you, acc/loc/dat,’ mer/jer ‘my, our’). The reason for this apparent exception is that the ‘genitive’ pronoun is in fact a possessive pronoun, which formally does not belong to the paradigm, and hence, disturbs the picture.

There are several pieces of evidence to support this claim: (i) unlike regular genitives, the pronominal possessive forms take additional agreement suffixes; (ii) unlike regular genitives, the possessive forms show no syncretism with any other case; this is expected if they are not case forms, but unexplained otherwise; (iii) the ‘genitive’ ending -r (me-r/je-r ‘my, our’) shares diachronic origin with morphemes routinely classified as possessive markers and not as case markers, e.g., in Latin forms such as nos-te r ‘our.’

There is actually one homophony of ins with dat, but this is due to a phonological conflation (see Halle and Vaux 1998:n.7). I come back to this later on.

Needless to say, there are a number of questions that arise once cross-linguistic perspective is taken. Two issues deserve mentioning: (i) local cases show up at places that are not directly comparable; (ii) particular languages present challenges to the view expressed in (8) (the reviewers mention specifically Latin). I cannot possibly address these issues within the space of an article, and I can only provide references to places where these challenges are addressed. For local cases, see Caha (2009:Chap. 3.4.3–4) and Caha (2011a). For cross-linguistic issues (including the discussion of Latin), see Caha (2009:Chaps. 3 & 8).

It cannot be decided whether attraction does or does not occur in the dative. Since the dative is always the same as the genitive, case attraction, if active, applies vacuously.

The rule in (30a) reads as follows: the feature matrix [+X, +Y], corresponding to nom, is realized by the phonology /phon A/.

Formally, the system makes some non-trivial predictions concerning syncretism. For example, if nom and gen are syncretic to the exclusion of other cases, then acc and loc cannot be. That is because both nom-gen and acc-loc syncretisms can be only obtained by inserting an exponent under the [case] node in the tree (27). Since only one marker can be inserted at a given node, the combination of the two syncretisms is impossible.

However, as far as I am aware, there is no known constraint on syncretism that has such an implicational format (if one type of syncretism is attested in a paradigm, then another type of syncretism cannot be, even though it is independently attested). If that is so, and such predictions find no empirical support, this in fact adds up to the drawbacks.

Schütze (2001) argues that English has a default accusative case, which in English is manifested only on pronouns. However, all the examples that are used to establish this claim (coordination, left dislocation, gapping, short replies) are contexts that exclude weak pronouns and require strong pronouns (see Cardinaletti and Starke 1999). This makes it more likely that the data rather suggest that ‘he/she’ are weak pronouns, whereas ‘him’ a strong pronoun, ambiguous for nom/acc.

An anonymous reviewer reminds me that he/she are available in (some) coordination structures (whereas weak pronouns generally are not, although some counterexamples have been reported)—I leave this for future research. The reviewer also notes that he/she can be contrasted and stressed; but these facts are compatible with being a weak pronoun (Cardinaletti and Starke 1999:153–154).

In a number of languages, the goal zone also comprises the allative (dat=all is frequent). But recall that the goal case in Classical Armenian is acc. The suggestion is that the acc is verb governed, and Armenian directionals thus correspond to applicatives.

In languages where the noun lands in between the case features, the features are split into two groups and get realized as two separate morphemes (one preceding, one following the noun). Hence, such languages also provide evidence for the proposed containment relations; see Caha (2011b) for a number of illustrations for each containment proposed.

I assume that agreement involves a separate base-generation of case features on top of the agreeing constituent, gen in our case. At LF, these features must match with the case features base-generated on the head noun.

In Old Georgian, agreement is in fact not optional, but depends on the position of the dependent noun. Simplifying things slightly, in post-nominal position, agreement applies; in pre-nominal position, it does not. I assume that in Classical Armenian, the gen noun also has access to two distinct positions, one where agreement is obligatory and one where it is disallowed. The existence of such two distinct positions is masked by the fact that the noun moves even higher up.

The example also has an accusative marker -n, which marks the whole DP, and surfaces following the first constituent of the DP.

I assume that in nom, acc, loc, Classical Armenian is thus forced to make use of the possessor position where agreement does not apply.

Admittedly, the facts do not provide evidence for such a rich structure as (28) posits. (We only have evidence for gen being a constituent inside dat/abl/ins.) But the point is that whenever we can find evidence for layering, we do.

These stages thus do not correspond to unchangeable phases, a notion that may be close to what Chomsky (2008:143) has in mind: “For minimal computation, as soon as the information is transferred it will be forgotten, not accessed in subsequent stages of derivation […] Working that out, we try to formulate a phase-impenetrability condition PIC […] PIC holds […] for the mappings to the interface.”

The view assumed here comes closer to the one described in Šurkalović (2011). Šurkalović (2011:97) proposes that “spell-out does not proceed in chunks but in concentric circles,” with the consequence that “the input to phonology at each phase is cumulative, consisting of the spell-out of the current phase together with the spell-out of the previous phases.” (Šurkalović 2011:84).

See Bobaljik (2002) for a related proposal.

In general, I assume that lexical entries are triplets 〈phonology, syntax, concept〉. Since the conceptual contribution of case affixes is negligible (if present), I ignore it here.

Further, I assume that lexical entries are links between phonological, syntactic and conceptual representations, each representation a well-formed object in the relevant module. This answers some frequent questions about why there should be syntactic trees ‘in the lexicon’ (see (43b)), and related worries about the role of syntax and the lexicon in constructing expressions. From the linking conception, it follows that the lexicon has no means to create structures of its own. Consequently, it follows that the only possible target of lexicalization (when it comes to the syntax part of the lexical entry) is a well-formed syntactic structure. Thus, for example, [X, Y, Z] cannot be a part of a lexical entry, because syntax cannot construct ternary branching trees (cf. Kayne 1994; Chomsky 1995). Thus, despite the fact that the lexicon stores outputs of syntax, it does not duplicate it; the lexicon only links the outputs of syntax to representations in other modules.

This analysis presupposes the Superset Principle; when -k‘ acts as a pure plural marker, it spells out a sub-constituent of its specification.

I have to mention that Plank (1999) identifies an additional minority pattern where—as Plank argues—there is agglutination in the grammatical cases, and fusion in the semantic cases. This pattern represents a counterexample to the theory presented here; but there are reasons to doubt its existence.

According to Plank, this pattern arises in Chechen, Archi, Georgian and (interestingly) Classical Armenian. Including Classical Armenian on the list of languages that exhibit agglutination in the grammatical cases (specifically nom) makes it obvious that Plank’s conclusions rest on the agglutinative analysis (nom=-ø+k‘). Once scrutinized, it turns out that 3 out of the 4 languages (Chechen, Archi, and Classical Armenian) are listed as agglutinating on the basis of an analysis that assumes a zero morpheme. This is a rather weak evidence.

Thus, what remains from the minority pattern under scrutiny is a single example: the so-called archaic plurals in Modern Georgian. I have to leave this example for future research.

In the ideal case, head-movement is treated as a special instance of phrasal movement. The analysis presented here does not allow such a reduction. The issue how to replace the type of head-movement I employ in this paper is subject to ongoing research in Nanosyntax.

A reviewer suggests that arbitrary thematic vowels are hard to account for ‘in syntax,’ and require the existence of a specific morphology module—contrary to the architectural claims made here. I do not agree with this conclusion for reasons I sketch below.

In particular, the selection between a particular root and an adequate thematic vowel can be treated as idiomatic (in a technical sense). Space considerations prevent me from developing a full fledged account of idioms, and I give only its bare bones. In Nanosyntax (cf. Starke 2010), idioms like kick the bucket are treated as phrasal lexical entries that make reference to other entries. Thus, when a bottom-up translation derives a constituent with its constituent parts spelled out as kick the bucket (as opposed to kick the pot), that triggers the insertion of the concept DIE. Similarly, the Armenian lexicon contains a number of idioms that refer to a constituent consisting of the root and a particular thematic vowel (cf. Marantz 1995). Noting that there are idioms that contain words which do not make sense out of that idiom, roots on their own may or may not have interpretation, depending on whether any conceptual information is associated to them outside of the particular idiom. Assuming an account along these lines, the pairing of roots and thematic vowels requires a specific morphological component no more than phrasal idioms do.

I assume that the NP is head final, and may contain adjectival modifiers. Note as well that pre-nominal adjectives do not carry agreement in Armenian.

A virtually identical situation obtains in the gen/dat.pl, since -c‘ is the only candidate for the spell-out of both the case and number branch of the bar node.

In addition, the explanation of Case Attraction in terms of ellipsis disappears under the markedness reversal.

I also assume that m in ins.pl is a phonological variant of the stem marker n.

In the present account, the ordering in loc, gen and dat is due to phrasal movement. The root moves above case, without pied-piping the stem marker along.

Note that an analysis in terms of a purely phonological process is not viable, or at least not obviously so. To be sure, Classical Armenian does exhibit vowel-zero alternations (Schmitt 1981:38–39); however, they follow a different pattern than the one we are dealing with here. Thus, in the prototypical instance, we have a vowel in a closed syllable am i s ‘month, nom.sg’ and a zero in an open syllable am ø s-u ‘month, gen.sg’. This regular pattern is different from the data at hand, where both zero mas- ø n ‘part, nom.sg’ and a vowel mas- i n-k‘ ‘part, nom.pl’ show up in a closed syllable. In other words, a theory based on epenthesis (as observed elsewhere in the language) would wrongly predict nom *mas-in. Cf. fn. 41.

There is a number of nouns that are apparently underived. In fact, Olsen (1999:156) notes that the declension type is so productive, that any noun whose acc.sg accidentally ended in the sequence Cn were re-analyzed as n-stems (i.e., C-n). I believe that these facts are compatible with the general view taken here, since in general, there is no obstacle in nominalizing nouns (recall ‘brotherhood’). Once again, the phrasal idiom view suggested in fn. 33 needs to be invoked.

This paradigm provides additional evidence against treating the vocalic marker as epenthetic. That is because the root is vowel final, and hence, the vowel does not improve the phonotactics in any way.

References

Abraham, Werner. 2003. The myth of doubly governing prepositions in German. In Motion, direction and location in languages: In honor of Zygmunt Frajzyngier, eds. Erin Shay and Uwe Seibert, 19–38. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ackema, Peter, and Ad Neeleman. 2007. Morphology ≠ syntax. In The Oxford handbook of linguistic interfaces, eds. Gillian Ramchand and Charles Reiss, 325–353. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baerman, Matthew. 2008. Case syncretism. In The handbook of case, eds. Andrej Malchukov and Andrew Spencer, 219–230. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baerman, Matthew, Dunstan Brown, and Greville G. Corbett. 2005. The syntax-morphology interface. A study of syncretism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark C. 1988. Incorporation: A theory of grammatical function changing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baker, Mark C., and Ruth Kramer. 2010. “Prepositions” as case morphemes inserted at PF in Amharic. Handout of a talk at the BCGL5 conference, 2–3 December, at CRISSP, Brussels.

Baltin, Mark. 2006. The non-unity of VP-preposing. Language 82: 734–766.

Bittner, Maria, and Ken Hale. 1996. The structural determination of case and agreement. Linguistic Inquiry 27(1): 1–68.

Blake, Barry J. 1994. Case, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2002. Syncretism without paradigms: Remarks on Williams 1981, 1994. In Yearbook of morphology 2001 eds. Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle, 53–86. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2012. Universals in comparative morphology: Suppletion, superlatives, and the structure of words. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2007. On comparative suppletion. Ms., University of Connecticut.

Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring sense: An exo-skeletal trilogy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Caha, Pavel. 2009. The Nanosyntax of case. PhD thesis, CASTL, University of Tromsø.

Caha, Pavel. 2011a. Case in adpositional phrases. Ms., CASTL, Tromsø.

Caha, Pavel. 2011b. The parameters of case marking and spell out driven movement. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 2010 10: 33–78.

Calabrese, Andrea. 2008. On absolute and contextual syncretism. In Inflectional identity, eds. Asaf Bachrach and Andrew Nevins, 156–205. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1999. The typology of structural deficiency: A case study of three classes of pronouns. In Clitics in the languages of Europe, ed. Henk van Riemsdijk, 145–233. Berlin: Mouton.

Carnie, Andrew. 2008. Constituent structure. Oxford: OUP.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta, 133–166. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo, and Luigi Rizzi. 2010. The cartography of syntactic structures. In The Oxford handbook of linguistic analysis, eds. Bernd Heine and Heiko Narrog, 51–65. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Embick, David, and Rolf Noyer. 2007. Distributed Morphology and the syntax–morphology interface. In The Oxford handbook of linguistic interfaces, eds. Gillian Ramchand and Charles Reiss, 289–324. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Guerssel, Mohand, and Jean Lowenstamm. 1996. Ablaut in Classical Arabic measure I active verbal forms. In Studies in Afroasiatic grammar, eds. Jacqueline Lecarme, Jean Lowenstamm, and Ur Shlonsky, 123–134. The Hague: HAG.

Haegeman, Liliane. 1994. Introduction to government and binding theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

Halle, Morris. 1997. Impoverishment and fission. In Papers at the interface, eds. Benjamin Bruening, Y. Kang, and Martha McGinnis. Vol. 30 of MITWPL, 425–449. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed Morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, eds. Kenneth Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Halle, Morris, and Bert Vaux. 1998. Theoretical aspects of Indo-European nominal morphology: The nominal declensions of Latin and Armenian. In Mir Curad: Studies in honor of Clavert Watkins. Jay Jasanoff, H. Craig Melchert, and Lisi Olivier. Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, 223–240. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck.

Harley, Heidi. 2008. When is syncretism more than a syncretism? Impoverishment, metasyncretism and underspecification. In Phi theory: Phi-features across modules and interfaces, eds. Daniel Harbour, David Adger, and Susana Béjar, 251–294. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1983. Semantics and cognition. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Jakobson, Roman. 1962. Beitrag zur allgemeinen Kasuslehre: Gesamtbedeutungen der russischen Kasus. In Selected writings, Vol. 2, 23–71. The Hague: Mouton.

Johnston, Jason Clift. 1996. Systematic homonymy and the structure of morphological categories. Some lessons from paradigm geometry. PhD thesis, University of Sydney.

Julien, Marit. 2007. On the relation between morphology and syntax. In The Oxford handbook of linguistic interfaces, eds. Gillian Ramchand and Charles Reiss, 209–238. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kayne, Richard S. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kayne, Richard S. 2005. Some notes on comparative syntax, with special reference to English and French. In The Oxford handbook of comparative syntax, eds. Guglielmo Cinque and Richard S. Kayne, 3–69. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1973. ‘Elsewhere’ in phonology. In A Festschrift for Morris Halle, eds. Paul Kiparsky and Steven Anderson. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Koopman, Hilda, and Anna Szabolcsi. 2000. Verbal complexes. Vol. 34 of Current studies in linguistics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2000. Building statives. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistic Society.

Krause, Todd B., and Jonathan Slocum. no date. Classical Armenian online. http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/eieol/armol-0.html.

Marantz, Alec. 1995. ‘Cat’ as a phrasal idiom: Consequences of late insertion in Distributed Morphology. Ms., MIT.

McCawley, James D. 1968. Lexical insertion in a transformational grammar without Deep Structure. In Papers from the fourth regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, eds. B. J. Darden, C.-J. N. Bailey, and A. Davidson. Chicago: University of Chicago.

McCreight, Katherine, and Catherine V. Chvany. 1991. Geometric representation of paradigms in a modular theory of grammar. In Paradigms: The economy of inflection, ed. Frans Plank, 91–112. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

McFadden, Thomas. 2007. Default case and the status of compound categories in Distributed Morphology. Penn Working Papers in Linguistics (Proceedings of PLC 30) 13.1: 225–238.

McFadden, Thomas. 2004. The position of morphological case in the derivation: A study on the syntax-morphology interface. PhD thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

Müller, Gereon. 2003. A Distributed Morphology approach to syncretism in Russian noun inflection. In Proceedings of FASL 12, eds. Olga Arnaudova, Wayles Browne, Maria Luisa Rivero, and Danijela Stojanovic, 353–374. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Muriungi, Peter. 2008. Phrasal movement inside Bantu verbs: Deriving affix scope and order in Kiitharaka. PhD thesis, CASTL, Tromsø.

Neeleman, Ad, and Kriszta Szendrői. 2007. Radical pro-drop and the morphology of pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 38: 671–714.

Olsen, Birgit Anette. 1999. The noun in Biblical Armenian. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Pantcheva, Marina. 2010. The syntactic structure of locations, goals, and sources. Linguistics 48: 1043–1081.

Pantcheva, Marina. 2011. Decomposing Path. The Nanosyntax of directional expressions. PhD thesis, CASTL, Tromsø.

Pesetsky, David. 1995. Zero syntax: Experiencers and cascades. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Phillips, Colin. 2003. Linear order and constituency. Linguistic Inquiry 34: 37–90.

Plank, Frans. 1991. Rasmus Rask’s dilemma. In Paradigms: The economy of inflection, ed. Frans Plank, 161–196. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Plank, Frans. 1995. (Re-)introducing suffixaufnahme. In Double case: Agreement by suffixaufnahme, ed. Frans Plank, 3–112. Oxford: OUP.

Plank, Frans. 1999. Split morphology: How agglutination and flexion mix. Linguistic Typology 3: 279–340.

Radkevich, Nina. 2009. Vocabulary insertion and the geometry of local cases. Ms., UConn, downloadable at: http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/000958.

Ramchand, Gillian. 2008. Verb meaning and the lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, Norvin. 2007. Lardil “case stacking” and the structural/inherent case distinction. Ms., MIT, downloadable at: http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/000405.

Schmitt, Rüdiger. 1981. Grammatik des Klassisch-Armenischen. Vol. 32 of Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck.

Schütze, Carson. 2001. On the nature of default case. Syntax 4(3): 205–238.

Starke, Michal. 2009. Nanosyntax. A short primer to a new approach to language. In Nordlyd 36: Special issue on Nanosyntax, eds. Peter Svenonius, Gillian Ramchand, Michal Starke, and Tarald Taraldsen. 1–6. Tromsø: University of Tromsø. Available at www.ub.uit.no/munin/nordlyd/.

Starke, Michal. 2010. Universal grammar vs. lexically driven derivations, once more. Talk at the SmaSh workshop. České Budějovice: University of South Bohemia, June 23.

Starke, Michal. 2005. Nanosyntax class lectures. Spring 2005, University of Tromsø.

Starke, Michal. 2011. Towards elegant parameters: Language variation reduces to the size of lexically stored trees. Transcript from a talk at Barcelona Workshop on Linguistic Variation in the Minimalist Framework. Available at http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/001183.

Šurkalović, Dragana. 2011. Modularity, linearization and phase-phase faithfulness in Kayardild. Iberia: An International Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 3(1): 81–118.

Taraldsen, Tarald. 2010. The Nanosyntax of Nguni noun class prefixes and concords. Lingua 120(6): 1522–1548.

Travis, Lisa. 1984. Parameters and effects of word order variation. PhD thesis, MIT.

Vangsnes, Øystein A. 2013. Syncretism and functional expansion in Germanic wh-expressions. Language Sciences 36: 47–65.

Weerman, Fred, and Jacqueline Evers-Vermeul. 2002. Pronouns and case. Lingua 112: 301–338.

Wiese, Bernd. 2003. Zur lateinischen Nominalflexion: Die Form-Funktions-Beziehung. Ms., IDS Mannheim.

Wiese, Bernd. 2004. Categories and paradigms. On underspecification in Russian declension. In Explorations in nominal inflection, eds. Gereon Müller, Lutz Gunkel, and Gisela Zifonun, 321–372. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Williams, Edwin. 1981. On the notions “lexically related” and “head of a word”. Linguistic Inquiry 12.2: 245–274.

Williams, Edwin. 1994. Remarks on lexical knowledge. Lingua 92: 7–34.

Acknowledgements

A number of people gave me comments and suggestions concerning the material presented here. I started working on the topic as a part of my dissertation-related research, and my supervisor Michal Starke has substantially influenced the initial stage of work. Jonathan Bobaljik and Hilda Koopman (in their capacity as committee members) have left their mark on this work as well, for which I am very grateful. In addition, a very early version of the paper was presented at WOTM 4 in Leipzig (2008), and I thank the audience there for feedback and interesting discussions.

Subsequently, Gillian Ramchand and Peter Svenonius have provided me with detailed comments on a draft of this material as it appeared in Nordlyd (Tromsø working papers in linguistics, 2009). Major changes have occurred in the first draft submitted to NLLT due to the comments from three anonymous reviewers, accompanied by an additional review by the handling NLLT editor, Gereon Müller. For the final round of comments, I am indebted to Marcel den Dikken. A very special thanks to Marina Pantcheva, who has read and commented on all these various versions.

I thank all these people for bringing up empirical challenges, pointing out problems of analysis, finding better ways of putting things, removing typos, correcting my English, and asking some big picture questions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caha, P. Explaining the structure of case paradigms by the mechanisms of Nanosyntax. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 31, 1015–1066 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9206-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9206-8