Abstract

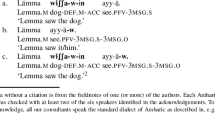

This paper introduces a new complementizer agreement relation to the theoretical literature from Lubukusu (Bantu, Kenya), in which a declarative-embedding complementizer agrees in an upward orientation with the subject of its selecting clause. The agreement relation is extensively documented in a wide variety of syntactic contexts including ditransitives, causatives, passives, and multiple embeddings, establishing the empirical generalization that the complementizer agrees with the most local superordinate subject. The paper proposes that this agreement relation is not a direct Agree relation, but is instead the result of local agreement between the complementizer and a null subject-oriented anaphor (whose antecedent is necessarily the superordinate subject). This is termed an Indirect Agree relation, defined as an instance of agreement between a head and an agreement trigger that is mediated by a different syntactic element (a null anaphor, in this case). A variety of evidence is given in support of this conclusion, including mismatched agreements between the complementizer and matrix subject agreement, lack of split anaphora, the properties of raising constructions, (tensed) clause-boundedness, and the intervention of specified subjects. A number of issues for future research are noted as well, including various complementation patterns relating to evidentiality, factivity, and sentience as they intersect with the properties of the agreeing complementizer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is often said that Lubukusu is a dialect of Luyia, but the Ethnologue’s terminology recognizes that there is no standard “Luyia” language; rather, each Luyia speaker speaks one of its varieties. There are estimated to be 17–23 Luyia languages, all with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility (Lewis 2009; Marlo 2009).

Note that for the course of this paper, when discussing complementizer agreement, I refer only to declarative-embedding complementizers, setting aside all discussion of relative and focus complementizers (which also bear agreement in a vast number of Bantu languages).

Although see Haegeman and van Koppen (2012) for a strong argument against Feature Inheritance using data from these same West Germanic varieties.

I should note that anecdotal evidence suggests to me that the agreement relation reported here for Lubukusu may be more widespread within the Bantu languages than our current knowledge reflects. It appears that some form of this agreement is present in related Luyia dialects (e.g., Luwanga) and may also occur in languages in Northwest and Southwest Tanzania (e.g., Kijita and Kikerewe), though this is unconfirmed. Obviously, much more work needs to be done to properly evaluate the relative rarity (or non-rarity) of these agreement patterns.

It should be noted that speakers have mixed responses to mbo. Some speakers feel it is not originally Lubukusu and was perhaps borrowed from a neighboring language, but all speakers that I encountered used it productively.

The use of nga requires the morpheme ne- to be prefixed to the verbal form embedded under nga. The exact nature of this ne- morpheme is still unknown, though it appears in a wide variety of contexts in Lubukusu (see Wasike 2007).

Class 1 is the exception to this rule: the class 1 nominal pre-prefix is [o-], whereas class 1 subject agreement is [a-]. As noted in the chart, class 1 (third person singular) complementizer agreement patterns with subject agreement rather than the pre-prefix.

It is important to note that inclusion of the author of the letter and the person whose face/appearance are being reporting is important for complementizer agreement to be licit. This relates to the properties of complementizer agreement relating to sentience, as discussed in Section 4.2.

I leave for future research the question of what principles govern agreement with conjoined phrases in Lubukusu.

Thanks to Mark Baker for encouraging me to pursue this analytical direction; see also Baker (2008) where a similar approach is suggested.

There are alternative formulations of this ‘upward-oriented’ Agree relation, for example, positing that interpretable features on the operator can probe downwards and value uninterpretable features in their c-command domain, on C in this case (cf. Pesetsky and Torrego 2007). The formulation of the Agree relation itself is not critical to this paper, however, except that it allow for agreement between a head and a phrase in its specifier.

I follow Rizzi (1997) in assuming that CPs are simplex unless more articulated structures are necessitated by the constructions at hand. In principle this could be a more typical ‘downward’ Agree relation (Chomsky 2000), for example, if the OP were in some CP projection below the agr-li complementizer. But given that there is no empirical evidence to support of such a conclusion, I assume the operator is in SpecCP for the purposes of this paper.

My gratitude to an anonymous NLLT reviewer for their insightful comments on a clarified approach to the presentation of this analysis.

This agreement relation is reminiscent of anaphoric agreement in early proposals of Lexical Functional Grammar, cf. Bresnan and Mchombo (1987).

Thanks to an anonymous NLLT reviewer for important criticisms and suggestions in this section.

I refer the reader to Safir (2004:Chap. 5) for his full arguments against the notion that the domains of anaphoric reference and movement are coterminous.

Following Safir (2004), I abstract away from the question of whether clitic movement is head movement or phrasal movement, assuming that a comparable landing site adjoined to T is available if clitic movement is to be interpreted as phrasal movement.

Admittedly, in the Lubukusu case the anaphor is a null operator in the first place, so it is not possible to evaluate whether the clitic movement is overt or covert at all.

Note that the logical subject has a very similar meaning whether expressed as a possessor or as a locative adjunct (‘Alfred’s certainty’ vs. ‘certainty in Alfred’).

It should be noted that I am unaware of any morphosyntactic differences in Lubukusu between a passive with an implicit agent and one without it. This leads to a situation where there is simply variation as to whether speakers accept agreement with a derived subject in a passive. When presented with a large collection of sentences such that speakers do not dwell on any single sentence, they readily accept agreement with the derived subject of the passive. The tendency, rather, was that when speakers became consciously aware of the implicit agent in the passive construction, they rejected the complementizer agreement with the derived subject of the passive.

Or sometimes [ka-] in Lubukusu.

Note that the term “alternative agreement effect” is adopted here, a slight modification of the more familiar term “anti-agreement effect” which is adopted in the general literature on such phenomena (see Diercks 2010). This is due to the fact that this effect is not a lack of agreement, but rather a feature-deficient agreement form (Diercks 2010; Henderson 2009, 2011).

The precise nature of the empty category in these expletive constructions is very much an open question. Different verbs necessarily trigger different noun class agreement in these ‘expletive’ contexts, and speakers feel strongly that these constructions trigger an interpretation along the lines of ‘the evidence seems that …’. So it is not clear that these are truly expletive constructions in the sense that their subjects have no role except fulfilling the EPP. That being said, they nonetheless demonstrate the raising properties relevant to our discussion here.

Here, as above, the embedded clause is tensed and agreeing, potentially headed by a complementizer (e.g., mbo).

On McGinnis’ (2004) analysis, this difference correlates with whether the movement in question is Case-driven or EPP-driven, a correlation which is borne out in the type of Applicative heads that are realized in a particular (double object) construction. I approach this argumentation from the perspective of the phase-edge requirement, especially since the context of the ambiguity in the Lubukusu complementizer agreement cases is at the CP-level, not the ApplP-level. I refer the reader to McGinnis (2004) for the full details of her account.

I set aside the problematic issue of whether this SpecCP position is an A′-position (leading to an improper movement chain where A′-movement feeds A-movement to matrix subject position), though for discussion of this issue in a related language see Obata and Epstein (2011).

A much more extensive treatment of the benefits and drawbacks of an Agree approach to Lubukusu complementizer agreement is taken up in Diercks (2010), to which I refer the reader.

There are in fact other analytical possibilities, but space limitations prohibit a full discussion of them all. One particular analysis worth noting is that the null operator in SpecCP is PRO, not an anaphor, whose reference is controlled by an obligatory control relationship with the subject. While I refer the reader to Diercks (2010) for more argumentation against this analysis, I will let it suffice to note here that object-control verbs like tell (which control PRO in an embedded non-finite clause) nonetheless result in subject-controlled complementizer agreement, leading me to rule out control as a viable mechanism for constraining the subject-orientation of complementizer agreement in Lubukusu.

See also Haegeman and van Koppen (2012) on an argument against Feature Inheritance, in that case from West Germanic complementizer agreement.

It is an important question whether non-agreeing bali is a distinct complementizer from the agreeing complementizer, or whether it is the same syntactic element, but is realized as a default form in certain contexts. As will be seen below, in because-phrases and if-clauses (Section 4.2) the non-agreeing bali can occur in a variety of contexts in which the agreeing complementizer is impossible, patterning with the generic complementizer mbo. I interpret these facts structurally, claiming that non-agreeing bali occurs in a different position from the agreeing complementizer, explaining their distinct distributions. As pointed out to me by Paul Portner, an alternative analysis could be that they in fact occur in the same structural positions, but agreement on the complementizer is ruled out in certain structural contexts and a default form results. I set aside these questions as matters for future research.

Apparent exceptions to this generalization are khububu ‘to be jealous’ and khufukilila ‘to agree.’ I leave it to future research to determine whether these are true counter-examples to the generalization, or if these verbs actually have different semantic properties than their direct English translations. Specifically, it needs to be tested whether they always presuppose the truth of their complement clause, or whether they may (at times) treat the content of their complement clause as an assertion rather than as a presupposition. This requires much more knowledge of the syntactic/semantic properties of complementation in Lubukusu and perhaps Bantu more broadly, an area which is largely unresearched to my knowledge.

I must leave it for future research to establish a full picture of syntactic correlates of factivity in Lubukusu.

See Diercks (2010) for additional data in this same paradigm.

Note the addition of some additional agreement forms not included in the previous examples.

Culy (1994a) distinguishes these pronouns from the sorts of ‘logophoric’ pronouns that occur in Japanese, Icelandic, and Italian (for example), which are reflexive pronouns that may be bound either inside their clause or outside of their clause (see Sells 1987, among others). Culy refers to these latter pronouns in their “logophoric” uses as non-clause-bounded reflexives (NCBRs), and refers to the former as “pure” logophoric pronouns.

As a reviewer points out, another strong possibility may have to do with the evidential properties of the various complementizers in Lubukusu: if non-agreeing complementizers are capable of triggering an interpretation where the matrix subject doubts the interpretation of the embedded clause, the unlikely nature of such a situation in a sentence like (121) might account for the unacceptability of the non-agreeing complementizers. As with all the facts in this section, this issue requires much further research.

References

Adesola, Oluseye. 2006. A-bar dependencies in the Yoruba reference-tracking system. Lingua 116: 2068–2106.

Adesola, Oluseye. 2005. Pronouns and null operators—A-bar dependencies and relations in Yoruba. PhD diss., Rutgers University, New Brunswick.

Andersson, Lars-Gunnar. 1975. Form and function of subordinate clauses. PhD diss., Göteborg Universitet, Göteborg.

Austen, Cheryl Lynn. 1974a. Anatomy of the tonal system of a Bantu language. Studies in African Linguistics 5: 21–34.

Austen, Cheryl Lynn. 1974b. Aspects of Bukusu syntax and phonology. PhD diss., Indiana University, Bloomington.

Baker, Mark. 2008. The syntax of agreement and concord. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bearth, Thomas. 1971. L’énoncé Toura (Côte D’ivoire). Norman: Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of Oklahoma.

Bell, Arthur. 2004. Bipartite negation and the fine structure of the negative phrase. PhD diss., Cornell University, Ithaca.

Bell, Arthur, and Aggrey Wasike. 2004. Negation in Bukusu. Paper presented at the 35th annual conference on African linguistics, Boston, MA.

Boeckx, Cedric. 2003. Islands and chains: Resumption as stranding. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Bowers, John. 2002. Transitivity. Linguistic Inquiry 33: 183–224.

Bowers, John. 2010. Arguments as relations. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Braconnier, Cassian. 1987–1988. Kò/Nkò À Samatiguila. Mandenkan 14–15: 47–58.

Bresnan, Joan, and Sam Mchombo. 1987. Topic, pronoun, and agreement in Chichêwa. Language 63: 741–782.

Carlson, Robert. 1993. A sketch of Jɔ, a Mande language with a feminine pronoun. Mandenkan 25: 1–109.

Carstens, Vicki. 2003. Rethinking complementizer agreement: Agree with a case-checked goal. Linguistic Inquiry 34: 393–412.

Carstens, Vicki. 2005. Agree and EPP in Bantu. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 23: 219–279.

Carstens, Vicki. 2010. Implications of grammatical gender for the theory of uninterpretable features. In Exploring crash proof grammars, ed. Michael Putnam, 31–57. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Carstens, Vicki. 2011. Hyperactivity and hyperagreement in Bantu. Lingua 121: 721–742.

Carstens, Vicki, and Michael Diercks. to appear. Parameterizing Case and activity: Hyper-raising in Bantu. In Proceedings of NELS 40, Amherst: GLSA.

Chomsky, Noam. 1973. Conditions on transformations. In A festschrift for Morris Halle, eds. Stephen Anderson and Paul Kiparsky, 232–286. New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston.

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Knowledge of language: Its nature, origin and use. New York: Praeger.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–155. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Clements, George. 1975. The logophoric pronoun in Ewe: Its role in discourse. Journal of West African Languages 10: 141–177.

Cloarec-Heiss, France. 1986. I. Banda-Linda De Ippy, Ii. Les modalités personnelles dans quelques langues Oubanguiennes. Paris: Société d’Études Linguistiques et Anthropologiques Francaises.

Cole, Peter, and Li-May Sung. 1994. Head movement and long-distance reflexives. Linguistic Inquiry 25: 355–406.

Collins, Chris. 2004. The agreement trigger. In Triggers, eds. Anne Breitbarth and Henk van Riemsdijk, 115–136. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Collins, Chris. 2005. A smuggling approach to the passive in English. Syntax 8: 81–120.

Culy, Christopher. 1994a. Aspects of logophoric marking. Linguistics 32: 1055–1094.

Culy, Christopher. 1994b. A note on logophoricity in Dogon. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 15: 113–125.

de Blois, Kornelis Frans. 1975. Bukusu generative phonology and aspects of Bantu structure. Tervuren: Royal Museum for Central Africa.

de Cuba, Carlos. 2007. On (non)factivity, clausal complementation, and the CP-field. PhD diss., Stony Brook University, Stony Brook.

de Wolf, Jan, and Kornelis Frans de Blois. 2005. Bukusu stories: Sixty Chingano from western Kenya. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Diercks, Michael. 2009. Subject extraction and (so-called) anti-agreement effects in Bukusu: A criterial freezing approach. In Proceedings of annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society 45(1), eds. Ryan Bochnak, Nassira Nicola, Peet Klecha, Jasmin Urban, Alice Lemieux, and Christina Weaver, 55–69. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Diercks, Michael. 2010. Agreement with subjects in Lubukusu. PhD diss., Georgetown University, Washington, DC.

Diercks, Michael. 2011. The morphosyntax of Lubukusu locative inversion and the parameterization of agree. Lingua 121: 702–720.

Diercks, Michael. 2012. Parameterizing Case: Evidence from Bantu. Syntax 15: 253–286.

Frampton, John, and Sam Gutmann. 2000. Agreement as feature sharing. Ms., Northeastern University, Boston.

Fuß, Eric. 2005. The rise of agreement: A formal approach to the syntax of grammaticalization of verbal inflection. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Giorgi, Alessandra. 1984. Toward a theory of long-distance anaphora. A GB approach. The Linguistic Review 3: 307–359.

Haegeman, Liliane. 1992. Some speculations on argument shift, clitics, and crossing in West Flemish. Ms., University of Geneva, Geneva.

Haegeman, Liliane, and Marjo van Koppen. 2012. Complementizer agreement and the relation between C∘ and T∘. Linguistic Inquiry 43: 441–454.

Hegarty, Michael. 1992. Familiar complements and their complementizers: On some determinants of A′-locality. Ms., University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Henderson, Brent. 2009. Anti-agreement and [Person] in Bantu. In Selected proceedings of the 38th annual conference on African linguistics: linguistic theory and African language documentation, eds. Masangu Matondo, Fiona Mc Laughlin, and Eric Potsdam, 173–181. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Henderson, Brent. 2011. Agreement and person in anti-agreement. Ms., University of Florida, Gainsville.

Heycock, Caroline. 2006. Case #35: Embedded root phenomena. In The Blackwell companion to syntax 2, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 174–209. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hoekstra, Eric, and Caroline Smits. 1998. Everything you always wanted to know about complementizer agreement. In Proceedings of the western conference on linguistics (WECOL), eds. E. van Gelderen and V. Samiian, Vol. 10, 189–200. Fresno: California State University.

Hooper, Joan, and Sandra Thompson. 1973. On the applicability of root transformations. Linguistic Inquiry 4: 465–497.

Hyams, Nina, and Sigríður Sigurjónsdóttir. 1990. The development of “long-distance anaphora”: A cross-linguistic comparison. Language Acquisition 1: 57–93.

Hyman, Larry. 1979. Phonology and noun structure. In Aghem grammatical structure, Southern California occasional papers in linguistics 7, ed. Larry Hyman, 1–72. Los Angeles: USC Department of Linguistics.

Hyman, Larry, and Bernard Comrie. 1981. Logophoric reference in Gokana. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 3: 19–37.

Idiatov, Dmitry. 2010. Person–number agreement on clause linking markers in Mande. Studies in Language 34: 832–868.

Innes, Gordon. 1971. A practical introduction to Mende. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1971. Some observations on factivity. Papers in Linguistics 4: 55–69.

Kawasha, Boniface. 2007. Subject-agreeing complementizers and their functions in Chokwe, Luchazi, Lunda, and Luvale. In Selected proceedings of the 37th annual conference on African linguistics, eds. Doris Payne and Jaime Peña. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Kayne, Richard S. 1975. French syntax: The transformational cycle. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kiparsky, Paul, and Carol Kiparsky. 1971. Fact. In Semantics. An interdisciplinary reader in philosophy, linguistics and psychology, eds. Danny Steinberg and Leon Jakobovits, 345–369. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koopman, Hilda. 2006. Agreement configurations: In defense of the “Spec head”. In Agreement systems, ed. Cedric Boeckx, 159–200. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Koopman, Hilda, and Dominique Sportiche. 1989. Pronouns, logical variables, and logophoricity in Abe. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 555–588.

Lebeaux, David. 1984. Locality and anaphoric binding. The Linguistic Review 4: 343–363.

Lewis, M. Paul, ed. 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the world, sixteenth edition. Dallas: SIL International.

Maho, Jouni. 2008. Nugl online: The web version of the new updated Guthrie list, a referential classification of the Bantu languages. http://goto.glocalnet.net/maho/bantusurvey.html. Accessed 1 September 2011.

Marlo, Michael. 2009. Luyia tonal dialectology. Talk given at The University of Nairobi, December 2009.

Marlo, Michael, Adrian Sifuna, and Aggrey Wasike. 2008. Lubukusu-English dictionary. Ms., University of Missouri.

McGinnis, Martha. 2004. Lethal ambiguity. Linguistic Inquiry 35: 47–95.

Obata, Miki, and Samuel David Epstein. 2011. Feature-splitting internal merge: Improper movement, intervention, and the A/A′-distinction. Syntax 14: 122–147.

Ouali, Hamid. 2008. On C-to-T phi-feature transfer: The nature of agreement and anti-agreement in Berber. In Agreement restrictions, eds. Roberta D’Alessandro, Gunnar Hrafn Hrafnbjargarson and Susann Fischer, 159–180. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Paré, Moïse. 1998. L’énoncé Verbal En Sān (Parler De Yaba). Ouagadougou: Université de Ouagadougou.

Perez, C. Harford. 1985. Aspects of complementation in three Bantu languages. PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Pesetsky, David, and Esther Torrego. 2007. The syntax of valuation and the interpretability of features. In Phrasal and clausal architecture, eds. Simin Karimi, Vida Samiian, and Wendy Wilkins, 262–294. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Pica, Pierre. 1987. On the nature of the reflexivization cycle. In Proceedings of NELS 17, eds. Joyce McDonough and Bernadette Plunkett, Vol. 2, 483–499. Amherst: UMass GLSA.

Richards, Marc. 2007. On feature inheritance: An argument from the Phase Impenetrability Condition. Linguistic Inquiry 38: 563–572.

Richards, Norvin. 2001. Movement in language: Interactions and architectures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1986. On chain formation. In The syntax of pronominal clitics, Syntax and semantics 19, eds. Stephen Anderson and Hagit Borer, 65–95. Orlando: Academic Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. L. Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Safir, Ken. 2004. The syntax of anaphora. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schneider-Zioga, Patricia. 2007. Anti-agreement, anti-locality, and minimality: The syntax of dislocated subjects. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25: 403–446.

Sells, Peter. 1987. Aspects of logophoricity. Linguistic Inquiry 18: 445–479.

Shlonsky, Ur. 1994. Agreement in comp. The Linguistic Review 11: 351–375.

Sigurðsson, Halldor Armann. 1986. Moods and (long-distance) reflexives in Icelandic. In Working papers in Scandinavian syntax 25. Trondheim: Linguistics Department, University of Trondheim.

Speas, Margaret. 2004. Evidentiality, logophoricity, and the syntactic representation of pragmatic features. Lingua 114: 255–276.

Tenny, Carol, and Margaret Speas. 2003. Configurational properties of point of view roles. In Asymmetry in grammar: Syntax and semantics, ed. Anna Maria Di Sciullo, 315–344. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Wasike, Aggrey. 2007. The left periphery, wh-in-situ and A-bar movement in Lubukusu and other Bantu languages. PhD diss., Cornell University, Ithaca.

Wasike, Aggrey. 2002. On the lack of true negative imperatives in Lubukusu. Linguistic Analysis 32: 584–614.

Watanabe, Akira. 2000. Feature copying and binding: Evidence from complementizer agreement and switch reference. Syntax 3.3: 159–181.

Zanuttini, Raffaella. 2008. Encoding the addressee in the syntax: Evidence from English imperative subjects. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26: 185–218.

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2010. There is only one way to agree. Presented at GLOW 33, April 2010.

Zwart, C. Jan-Wouter. 1997. Morphosyntax of verb movement. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this material appeared as a chapter in my dissertation (Diercks 2010), and some portions of this paper (with an earlier version of the analysis) appear in the proceedings of NELS 41. I owe a massive debt to the speakers of Lubukusu who worked with me over the course of this project, including Vivian, Jeremiah, and Rachel Lusweti, Justine Sikuku, Adrian Sifuna, Christine Nabutolah, and Maurice Sifuna, and to Alfred Anangwe for his invaluable assistance in orchestrating my fieldwork in Kenya. Justine Sikuku, Mark Baker, Ruth Kramer, Raffaella Zanuttini, Paul Portner, and Vicki Carstens all provided essential comments and criticisms, as well as Matthew Tucker, Peter Jenks, Jong Un Park, Omer Preminger, Amy Rose Deal, Masha Polinsky, Dan Seely, Carlos de Cuba, Mike Putnam, and Brent Henderson. Thanks also to Kaya LeGrand for her invaluable assistance editing the final version of the paper. I also am grateful for the comments and insights of audiences at Moi University and Harvard University, at the Mid-America Linguistics Conference @ the University of Missouri, at the LSA meeting in Baltimore, and at NELS at the University of Pennsylvania. I’d particularly like to thank the NLLT reviewers, whose very constructive suggestions, comments, and criticisms have made this a much better paper than it would have been otherwise. Portions of this research were performed with the support of a Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant from the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Diercks, M. Indirect agree in Lubukusu complementizer agreement. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 31, 357–407 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9187-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9187-7