Abstract

Many languages display correlations between subject-verb agreement and subject extraction that have come to be known as anti-agreement effects. This paper explores an anti-agreement effect found in many Bantu languages whereby a third person singular human subject triggers a unique verbal agreement marker when the subject is extracted. It is argued that co-variation of certain morphological properties of constructions with subject extraction points to an agreement relation between C and T underlying the anti-agreement effect, a conclusion that converges with proposals from Richards (2001) and Boeckx (2003) about the nature of extraction. I also argue that although this agreement relationship involves full sets of phi-features, the differing values acquired by the feature [person] in the nominal and verbal domains often makes it appear as if [person] is uniquely affected in anti-agreement contexts. Finally, I argue that variation in how anti-agreement is spelled out in a language is determined by morphological quirks of the language, especially the organization of its agreement paradigm. I illustrate this latter point using the framework of distributed morphology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

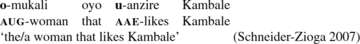

I restrict attention in this paper to subject relative clauses to allow for more consistent comparisons and because the relative marker plays a crucial role in the discussion; however, there are other contexts in Bantu where AAEs are typical. In general, Bantu languages lack wh-movement in questions, but many require that questioned subjects be clefted. Other languages, such as Kinande, have wh-movement with focused elements that resembles but may be distinct from clefting (see Schneider-Zioga 2007). AAEs are characteristic of these contexts as well.

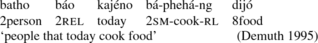

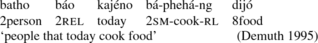

Following Cheng, I have spelled out the relative marker (REL) and the anti-agreement morphemes (AAE) separately in (4b). In natural speech, however, these would be collapsed into a single long vowel.

Here and throughout I mark tone where it indicated in the source material of cited data. Unfortunately, I did not mark tone when eliciting original data and these data appear without tone marking. Unless another source is cited, Bemba data are from Patricia Mupeta (p.c.).

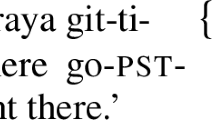

This assumption is based on analogy with an argument from Demuth (1995) for Sotho. Demuth demonstrates that a topicalized adverb results in a full demonstrative-like relative marker even in subject relatives, using this to argue that in (i) the subject/relative prefix is a portmanteau morpheme composed of a phonologically collapsed relative demonstrative and the regular subject agreement prefix.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

While this argument is persuasive, the facts cannot be repeated for Bemba (as Cheng notes) and there is no guarantee that the two languages are the same in this regard. Furthermore, Demuth does not rule out the possibility that the presence of the topic in the Sotho example in (ii) is triggering the use of a distinct relativization strategy rather than simply a phonological effect.

-

(i)

Cheng assumes a head-raising analysis of relatives, à la Kayne (1994), in which the relativized NP starts out within the clause in its case position before being extracted to SpecCP. Under her account, this requires raising the head NP of the relative clause through two specifiers of CP. Below, I follow Cheng in assuming the head-raising analysis; however, I assume a single CP specifier position.

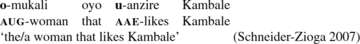

In an important series of articles on this topic, Schneider-Zioga (2000, 2007) also invokes anti-locality as a partial way to account for AAEs. Briefly, Schneider-Zioga argues that canonical subjects in Kinande reside in the left periphery, co-indexed with a null resumptive pro in SpecIP. Since extracting left peripheral subjects to another left peripheral position for focus or relativization would violate anti-locality, Schneider-Zioga shows convincingly that to-be-extracted subjects start out in SpecIP. Assuming that only non-structurally case-marked NPs may undergo extraction in Kinande, Schneider-Zioga argues that unlike canonical agreement, AAEs cannot assign case. Its occurrence thus enables extraction of subjects in SpecIP by virtue of denying them case. Though this is quite a different approach to Bantu AAEs than that of Cheng (2006), the two have in common that they seem to have no way to explain why AAEs are limited to class 1 nouns and why the AAE morpheme has the shape that it does.

Following standard assumptions (see Chomsky 2000, 2001), I take an Agree relation to consist of two sequential components: (i) a Match relation established between a set of unvalued features (a ‘probe’) and a c-commanded set of valued features (a ‘goal’), and (ii) a valuation operation (Agree) that assigns the value of the latter set of features to the former. Movement is not required for Match/Agree to take place. Rather, movement takes place in response to other features (the EPP in Chomsky 2000, 2001; ‘feature strength’ in Chomsky 1995; Richards 2001. I adopt the latter terminology here.).

A reviewer asks why the situation is not reversed; that is, why doesn’t the higher feature come into agreement with the lower feature instead? After all, this is the typical situation with agreement: the features of a c-commanding probe become identical to those of a lower goal. Under the system of strong chain violation and repair argued for in Boeckx (2003), however, the trigger for this Agree relation is two strong features in the same chain. If the second instance of movement isn’t to be phonologically vacuous, it must be the feature strength of the higher feature that is retained by this Agree operation. Since conflicting feature strengths are resolved by resulting feature identity, the lower feature must become identical with the higher feature and not vice versa. The fact that in AAEs it always seems to be the phi features of T (and not C) that are affected could thus be taken as an argument that the C-T Agree relation underlying AAEs takes place for the purpose of repairing a ‘strong chain’ PUC violation in Boeckx’s sense.

Boeckx’s (2003) system also seeks to explain why one often finds local subject resumption exactly in the contexts in which one does not find AAEs: when the Agree repair strategy is blocked, the stranding strategy (resumption) must be employed. This is applicable to the Swahili facts discussed below.

Object agreement in Swahili is required with most animate objects and possible (under certain semantic conditions) with inanimate objects.

A reviewer asks about cases in which there is no agreement and also no resumption between strong positions. One can imagine, say, a language with obligatory object agreement which does not display such agreement or a resumptive pronoun when the object is extracted. I have not come across such a language in the Bantu family. If such a language were found, it would certainly be a challenge to the Boeckx/Richards system. I reiterate that a full defense of that system is beyond the scope of this paper.

In fact, Schneider-Zioga (2000) also makes the argument that AAEs in the lower clause are due to local movement to SpecCP of the lower clause, though her account of AAEs differs from the one proposed here. As a reviewer points out, in the case where AAEs do not surface in the lower clause, as in (16a), one might assume that movement is not strictly local, but takes place in one fell swoop. Alternatively, it might be assumed that the lower C simply lacks phi-features and therefore C-T agreement is not possible and resumption is required.

I hasten to note this account is not complete because it does not explain why the subject resumptive pronoun in (18a, 18b) must be overt even though subject-related phi-features capable of licensing a null pro subject are present in T. I must leave this for future work.

Boeckx (2003:88) also invokes the verbal nature of complementizers in order to explain the possibility of local subject resumption in Edo. However, he claims this is because such complementizers are a part of serial verb constructions. In Swahili, this is unlikely, as serial verb constructions are not possible.

This is not to say, however, that all languages that lack an agreeing complementizer will necessarily lack AAEs since other language-specific morpho-phonological factors may come into play. For example, both Kirundi and Kinyarwanda, two closely related languages, lack relative complementizers. However, while Kirundi lacks AAEs, Kinyarwanda does not (for data, see Kimenyi 1980:61 for Kinyarwanda, and Sabimana 1986:189 (1a, 2a) for Kirundi). On the present approach, the conclusion must be that Kinyarwanda has phi-features in C but does not express them morpho-phonologically, while Kirundi must lack such features altogether.

However, there are exceptions here as well. A reviewer notes that in Nguni Bantu languages, contrastively focused NPs in clefts as well as in V-S inversion constructions display the augment vowel.

See Diercks (2009) for an account of anti-agreement in Lubukusu in a similar spirit to the present account. Unlike Bemba, Lubukusu has full CV initial prefixes.

The idea that a relativized NP and relative complementizer may agree in referentiality is not new. As an anonymous reviewer reminded me, Choueri (2002) discusses correlations between definite and indefinite relativized noun phrases and the types of relative complementizers that occur with them in Lebanese Arabic.

This ‘replacement’ is also strongly supported by the fact that first and second person singular pronouns, when relativized, also trigger AAEs. These facts are discussed in Sect. 3.2.2 below.

The phonological correlation is not absolute. In Kinande, e.g., the AAE morpheme and the initial vowel of the relative marker (and relativized NP) are not identical. This should not be taken as contrary evidence, however, since the present account does not rule out the fact that two sets of identical phi-features could be spelled out in different ways (much as a set of subject-related phi-features may be spelled out differently than object-related ones). I take such cases to be instances of contextual allomorphy.

-

(i)

-

(i)

As a reviewer points out, this approach requires that the phi-features in T remain ‘active’ and therefore able to be (re-)valued by the phi-features in C even though they have already been valued by the inherent phi-features of the NP subject. While not uncontroversial, this assumption is unproblematic as long as one does not assume that phi-features become inactive for further checking once they have been valued. For instance, Henderson (2006, 2011) assumes a notion of ‘Dynamic Locality,’ proposing that a probe may enter into several different Agree relations in the course of a derivation, with the most local relation being determined only at the end just before Spell-Out. It is this relation that serves as the source of the final value of the probe, despite any other Agree relations established earlier in the derivation. Note, however, that whatever the mechanics of this revaluation, this assumption is not a license for rampant revaluation of feature values in the derivation since revaluation here is a last resort operation induced by a strong chain violation.

There is further evidence that [person] in T is affected by AAEs in contexts where first and second person pronouns are extracted. I present such data below in (27) for KiLega and (36, 37) for Bemba.

Based on these data, Kinyalolo (1991) in fact explicitly argues that the anti-agreement phenomenon (which he terms ‘wh agreement’) uniquely involves the feature [person], proposing that AAEs (what he terms u-AGR) are underspecified for person. The generalization (27) demonstrates also holds for Bemba and Swahili.

Carstens (2008) argues that AAEs in Bantu arise due to the fact that [person] and [operator] are alternative values for the same feature, both located in D within DPs. AAEs on this view are simply alternative agreement forms, sensitive to this distinction. Thus, when a subject is an operator (as in extraction contexts like relatives or questions), agreement is with [operator], [gender], [number] rather than [person], [gender], [number]. On this view, AAE and non-AAE contexts do not differ in the mechanics of Agree, only in the values that the [person] receives. Examining AAEs in Berber and attempting to derive lexical categories computationally from phi-features, Ouhalla (2005) argues that the feature [person] defines the verbal category while the feature [class] defines the nominal category (the feature [number] being category neutral). Ouhalla argues that in AAEs, the verb lacks a [person] feature, instead having a [class] feature. Thus, verb forms in AAE contexts are not really verbs at all, but nominals. This accounts for their participial nature in Berber and some other languages. From an empirical standpoint, neither account is fully satisfactory. Since AAEs are merely operator agreement in Carstens’ analysis, it is not clear how it can account for locality effects that typically accompany AAEs, such as the fact that extraction of a subject operator from an embedded clause does not induce AAEs on the embedded verb in many languages, including Bantu languages such as Bemba. As for Ouhalla, the conclusion that AAEs always result in a nominal category seems too strong. While in Berber and some other languages the verb appears as a participle in AAE contexts, this is not true in Bantu languages. Other than the agreement difference in third singular human nouns, verb forms in AAE contexts may exactly resemble their non-AAE counterparts, able to carry overt marking for tense, aspect, and object marking. Note that the present approach in some way refines and combines these proposals. Like Carstens, the present approach argues for alternative values of the feature [person]; however, I take the relevant distinction to be between the values of the feature [person] in the nominal and verbal domains. Thus, this account also has something in common with Ouhalla’s proposal that in AAE contexts a verbal feature is replaced by a nominal one. However, unlike Ouhalla, I assume this is limited to phi-feature values and does not necessarily result in a change in lexical category (though this is not, in principle, ruled out if all empirical issues could be worked out).

An interesting question arises about why the [person] feature in C and in T should be differently sensitive to [person] values on the NP. Presumably this has to do with the different functions of the CP and TP domains. While the latter is typically taken to be concerned with inflectional properties of the clause, the former is concerned with ‘referential’ properties of the clause, such as clause typing and discourse-linked information (see, for example, Grohmann’s 2000 discussion of prolific domains).

Another consequence of this view is that languages without an agreement paradigm that crucially depends upon [person] distinctions might show no AAEs at all, even if a C-T Agree relation is involved in subject extraction. English could be a candidate for such a language. Though, as a reviewer points out, this might seem to raise the question of falsifiability; the present account could easily be proven misguided. For example, a language that expresses (i) phi-features in C in extraction contexts, (ii) traditional person distinctions in subject-verb agreement, and (iii) no AAEs would be a significant challenge to the present account.

A reviewer points out that the present account is not, strictly speaking, a testing ground for Distributed Morphology, and I make no attempt to contrast the present account with other frameworks. However, I wish to point out that the DM framework does add to the elegance of the account since it provides a framework within which morpho-phonological rules specific to the AAE context are not required. Rather, the general rules that account for the distribution of the augment and regular agreement prefixes also provide the distribution of the AAE marker.

I assume that insertion of subject agreement morphemes takes place at a dissociated node inserted and adjoined to T after Spell-Out and before vocabulary insertion, a standard assumption in DM (see Harley and Noyer 1999).

Crucially, the Vocabulary Insertion rule may not specify any features that are not present in the target of insertion. They must be a subset of the features in the terminal node the rule is targeting for insertion.

Presumably, reference to third person would require that the PARTICIPANT node have a sister node under the REF node that would specify third person. I do not have space here to fully explore this possibility. Assuming such a node, however, the rules in VI rules above could be revised to refer to these features rather than the features [1], [2], [3] as they do.

References

Aoun, Joseph, and Audrey Li. 1990. Minimal disjointness. Linguistics 28: 189–203.

Baker, Mark. 2008. On the nature of the anti-agreement effect: Evidence from wh-in-situ in Ibibio. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 615–632.

Barrett-Keach, Camilla. 1986. Word-internal evidence from Swahili for AUX/INFL. Linguistic Inquiry 17: 559–564.

Boeckx, Cedric. 2003. Islands and chains: Resumption as stranding. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Bokamba, Eyamba. 1976. Relativization in Bantu languages revisited. In The second LACUS forum, ed. Peter A. Riech, 38–50. London: Hornbeam Press.

Boukhris, Fatima. 1998. Les clitiques en Berbère Tamazighte. PhD diss., University Mohamed V, Rabat, Morocco.

Brandi, Luciana, and Patrizia Cordin. 1989. Two Italian dialects and the null subject parameter. In The null subject parameter, eds. Otto Jaeggli and Ken Safir, 111–142. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Carstens, Vicki. 2001. Multiple agreement and case deletion: Against ϕ-(in)completeness. Syntax 3: 147–163.

Carstens, Vicki. 2008. Feature inheritance in Bantu. Ms., University of Missouri, Columbia, MO.

Cheng, Lisa. 2006. Decomposing Bantu relatives. In Proceedings of NELS, Vol. 36, 197–216.

Cheng, Lisa, and Nancy Kula. 2007. Phonological and syntactic phrasing in Bemba relatives. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 28: 123–148.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries. In Step by step: Essays on minimalism in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin et al., 89–155. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Choueri, Lina. 2002. Issues in the syntax of resumption: restrictive relatives in Lebanese Arabic. PhD diss., University of Southern, California, Los Angeles, CA.

Chung, Sandra. 1982. Unbounded dependencies in Chamorro grammar. Linguistic Inquiry 13: 39–77.

Demuth, Katherine. 1995. Questions, relatives, and minimal projection. Language Acquisition 4: 49–71.

Diercks, Michael. 2009. Subject extraction and (so-called) anti-agreement effects in Bukusu: A criterial freezing approach. In Proceeding of the Chicago Linguistics Society 45(1), eds. R. Bochnak et al., Chicago, IL, 55–69.

Gerdts, Donna. 1980. Antipassives and causatives in Halkomelem. Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 6: 300–314.

Grohmann, Kleanthes. 2000. Prolific peripheries: A radical view from the left. PhD diss., University of Maryland, College Park, MD.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20, eds. Ken Hale and Samuel J. Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1994. Some key features of distributed morphology. In Papers in phonology and morphology (MITWPL 21), eds. Andrew Carnie et al., Cambridge, MA, 275–288.

Harley, Heidi. 1994. Hug a tree: Deriving the morphosyntactic feature hierarchy. In Papers in phonology and morphology (MITWPL 21), eds. Andrew Carnie et al., Cambridge, MA, 289–320.

Harley, Heidi, and Rolf Noyer. 1999. State-of-the-article: Distributed morphology. GLOT International 4: 3–9.

Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002. Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language 78: 482–526.

Henderson, Brent. 2004. PF evidence for phases and distributed morphology. In Proceedings of the thirty-fourth annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, eds. Keir Moulton and Matthew Wolf, 255–265. Amherst: GLSA.

Henderson, Brent. 2006. The syntax and typology of Bantu relative clauses. PhD diss., University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, IL.

Henderson, Brent. 2009. Anti-agreement and [Person] in Bantu. In Selected proceedings of the 38th annual conference on African linguistics: Linguistic theory and African language documentation, eds. Masangu Matondo, Fiona McLaughlin, and Eric Potsdam, 173–181. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Henderson, Brent. 2011. Agreement, locality, and OVS in Bantu. Lingua 121 (5): 742–753.

Hyman, Larry, and Francis Katamba. 1993. The augment in Luganda: Syntax or pragmatics? In Theoretical aspects of Bantu grammar 1, ed. Sam Mchombo, 209–256. Stanford: CSLI.

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kimenyi, Alexandre. 1980. A relational grammar of Kinyarwanda. PhD diss., UCLA, Los Angeles, CA.

Kinyalolo, Kasangati. 1991. Syntactic dependencies and the spec-head agreement hypothesis in KiLega. PhD diss., UCLA, Los Angeles, CA.

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 1991. Some current issues in Turkish syntax. In Turkish linguistics today, eds. Hendrik Boeschoten and Ludo Verhoeven, 60–92. Leiden: Brill Publishers.

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 1997. On the syntax and morphology of relative clauses in Turkish. In Linguistic investigations, eds. K. Èmer, A. Kocaman, and S. Özsoy, 24–51. Ankara: Kebikeç Yaynlar.

Longobardi, Giusseppe. 2005. Toward a unified grammar of reference. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 24: 5–44.

Longobardi, Giuseppe. 2008. Reference to individuals, person, and the variety of mapping parameters. In Essays on nominal determination, eds. Alex Klinge and Henrik Müller, 189–211. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

McCloskey, James. 1990. Resumptive pronouns, A′-binding, and levels of representation in Irish. In The syntax of the modern Celtic languages. ed. Randall Hendrick. Vol. 23 of Syntax and semantics. 199–256. New York: Academic Press.

Nevins, Andrew. 2007. The representation of third person and its consequences for the person-case constraint. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25: 273–313.

Ngonyani, Deo. 1999. X°-movement in Kiswahili relative clause verbs. Linguistic Analysis 29 (1–2): 137–159.

Nurse, Derek, and Gerard Philippson. 2003. The Bantu languages. London: Routledge.

Ouali, Hamid. 2008. On C-to-T phi-feature transfer: The nature of agreement and anti-agreement in Berber. In Agreement restrictions, eds. R. D’Alessandro et al., 159–180. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Ouhalla, Jamal. 1993. Subject extraction, negation and the anti-agreement effect. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 11: 477–518.

Ouhalla, Jamal. 2005. Agreement features, agreement, and anti-agreement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 23: 655–686.

Phillips, Colin. 1996. Order and structure. PhD diss., MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Phillips, Colin. 1998. Disagreement between adults and children. In Theoretical issues in the morphology-syntax interface, eds. Amaya Mendikoetxea and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria, 173–212. San Sebastian: ASJU.

Progovac, Ljiljiana. 1993. Non-augmented NPs in Kinande as negative polarity items. In Theoretical aspects of Bantu grammar 1, ed. Sam Mchombo, 257–270. Stanford: CSLI.

Richards, Norvin. 2001. Movement in language: Interactions and architectures. London: Oxford University Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar: Handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Sabel, Joachim, and Jochen Zeller. 2006. Wh-question formation in Nguni. In African languages and linguistics in broad perspective (selected proceedings of the 35th annual conference of African linguistics, Harvard, Cambridge), eds. John Mugane, John Hutchison, and Dee Worman, 271–283. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Sabimana, Firmard. 1986. The relational structure of Kirundi verbs. PhD diss., Indiana University, Bloomington, IN.

Schafer, Robin. 1995. Negation and verb second in Breton. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 13 (2): 135–172.

Schneider-Zioga, Patricia. 2000. Anti-agreement and the fine structure of the left edge. In University of California Irvine working papers in linguistics 6, eds. Ruixi Ai, Francesca Del Gobbo et al., Irvine, CA. Available at http://hssfaculty.fullerton.edu/english/pzioga/for%20website/UCI_working_papers.pdf.

Schneider-Zioga, Patricia. 2002. The case of anti-agreement. In Proceedings of AFLA 8: Eighth meeting of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association, MITWIPL 8, eds. Andrea Rackowsky and Norvin Richards, 325–339. Cambridge: MIT.

Schneider-Zioga, Patricia. 2007. Anti-agreement, anti-locality and minimality: The syntax of dislocated subjects. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25 (2): 403–446.

Stowell, Tim. 1991. Determiners in NP and DP. In Views on phrase structure, eds. Katherine Leffel and Denis Bouchard, 37–56. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Walusimbi, Livingstone. 1996. Relative clauses in Luganda. Koln: Rudiger Koppe Verlag.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Cedric Boeckx, Eyamba Bokamba, Nancy Kula, Eric Potsdam and three anonymous reviewers for comments on this work. Also thanks to the participants of the 38th Annual Conference on African Linguistics at the University of Florida as well as the 45th Chicago Linguistic Society where earlier versions of this work were presented. Special thanks to Patricia Mupeta for providing or confirming all of the Bemba data in this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Henderson, B. Agreement and person in anti-agreement. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 31, 453–481 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9186-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9186-8