Abstract

The incidence of deep fungal infection due to non-albicans Candida species (especially Candida glabrata) has significantly increased in recent decades. Candida glabrata is an opportunistic pathogen of low virulence which mainly invades the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and respiratory tracts, but has rarely been reported as complication of articular surgery in the literature. We present a case of knee fungal arthritis caused by C. glabrata after a minimally invasive arthroscopic surgery. In this case, the patient’s knee got infected after arthroscopic treatment for a recurrent popliteal cyst, and she was unable to be cured by either debridement or antifungal drugs. Mycological and molecular identification of the necrotic tissues isolate revealed C. glabrata as etiologic agent. We originally planned to conduct a debridement once again, but it was found that the articular cartilage was extensively damaged during the operation. Besides, the magnetic resonance imaging of the affected knee also showed that the infection had invaded the subchondral bone. So we treated this case with a two-stage primary total knee arthroplasty with an antibiotic-laden cement spacer block. After a 10-month follow-up, the patient had completely recovered and has not experienced any recurrence to date. In addition, we review 21 cases of C. glabrata-induced infectious arthritis described to date in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Candida glabrata mainly causes systemic or mucosal infections in immunosuppressed patients due to the increased use of prophylactic antifungal treatment [1]. Infectious arthritis induced by C. glabrata after arthroscopic surgery has rarely been reported before [2, 3]. Here we would like to share a refractory C. glabrata-induced infectious knee case with extensive cartilage damage following an arthroscopic surgery for treating a recurrent popliteal cyst. According to our experience, our measure can be borrowed for complicated, refractory mycotic arthritis which failed by debridement or systemic antifungal treatment. And at the ending of this paper, a literature review of similar cases was analyzed.

Case Report

A 58-year-old woman was admitted for chronic pain, exudation, and poor wound healing of her left knee for 6 months after arthroscopy which was performed to deal with a recurrence of popliteal cyst (21 * 10 * 9 mm3) at the local hospital. However, redness, swelling, and effusion were observed around the affected knee from 15 days after the operation. All of the treatments including superficial debridement, irrigation, and a 2-month course of oral fluconazole did not work. The wound gradually formed an irregularly shaped abscess and a sinus tract with effusion. Her past medical history included diabetes mellitus with poor blood glucose control and chronic hepatitis B.

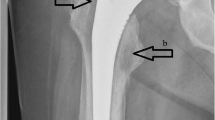

Physical examination revealed the presence of an 4.5 cm × 5.0 cm irregularly shaped abscess on the medial side and a circular sinus tract in diameter of 2 cm on the lateral side of her left knee (Fig. 1). Radiographs (X-ray and MRI) of the knee showed extensive destruction of the subchondral bone, popliteal cyst, and joint cavity effusion (Fig. 2). An articular cavity puncture was conducted firstly, and the puncture fluid and wound secretion were cultured. In the meantime, intravenous fluconazole (0.2 g/day) was empirically used initially. The inflammation marker showed C-reactive protein 40 mg/l and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 48 mm/h, and the G test result was 158 pg/ml.

A thorough debridement was originally planned to conduct once again. However, it was found that the knee articular cartilage was extensively damaged intraoperatively. So a two-stage surgical method was conducted to treat this case which is similar to our previous method to treat severe infectious arthritis caused by bacteria [4]. At the first stage, we conducted the osteotomy of distal femur and proximal tibia, then placing a well-designed antibiotic-laden bone cement spacer, combining it with a systematic antifungal drugs application to completely wipe out the pathogen.

The static cement antibiotic-loaded spacer was implanted with a total of 9 g of vancomycin, 2 g of gentamicin, and 200 g of cement. Postoperative radiographs showed a well-fixed static spacer (Fig. 3). Joint immobility of 6 weeks was executed. The histopathology stained with H&E showed hyperplastic and degenerative synovial tissue with extensive necrosis and peripheral granulomatous changes (Fig. 4). On Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA), the isolate formed shining, smooth, and cream-colored colonies. Acid-fast staining and bacterial cultures were negative. The isolate was sensitive to fluconazole (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC], 1 μg/ml), itraconazole (MIC, 0.125 μg/ml), voriconazole (MIC, 0.06 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (MIC, 0.5 μg/ml). For species molecular sequencing, the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rRNA gene was analyzed by PCR using primers ITS1 and ITS4. Amplification was carried out at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min 30 s. The PCR products were sequenced by the Shanghai Majorbio Company. The results showed that the fragment was consistent with a fragment from C. glabrata by submitting the gene sequence to BLAST for nucleotide comparison (homology was 100%; Genebank Number SCZ91521) tool (BLAST) algorithm (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) of the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

Amphotericin B was suggested to be the optimal treatment for this condition after consultation with infectious disease specialists and dermatologists. The creatinine was rapidly rose to 232 μmol/l after intravenous infusion of amphotericin B for 2 weeks (lipid formulation, 0.4 g/day). So intravenous application of voriconazole (0.16 g/day) had been treated instead for 3 months, and inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP) were monitored (Fig. 5). After the infection was eradicated (all inflammatory markers were negative, and no inflammatory symptom was observed), the second stage of a primary total knee arthroplasty was conducted 1 year after the arthrotomy to reestablish the knee function (Fig. 6). At a follow-up of 10 months, no persistence of infection or reinfection is observed.

Discussion

Arthroscopic knee surgery is minimally invasive and safe with low complication incidences (0.27–4.7% [5,6,7]). Infections of any kind are rarely reported yet the nerve-wracking complication of this surgery (0.84% [5]), especially with the fungal infection did occur. Overall incidence of fungal arthritis is relatively low due to non-albicans Candida species which is less than 1% of all arthritis cases but has increased in recent years due to the increasing application of corticosteroid, overuse of antibiotics, aging, and diabetes [8], although Candida albicans is still the most widespread isolated species and is the main pathogen of fungal knee arthritis [9]. Candida glabrata is a kind of special fungal species due to its acquisitive antifungal resistance, which may cause a devastating complication of articular surgery (such as arthroplasty, arthroscopy, and internal fixation). The progress of the C. glabrata infection is too hard to manage that leads to substantial utilization of healthcare resources. Candida glabrata is of special significance due to its upward trend in acquisitive antifungal resistance among Candida species [1].

Candida glabrata displays several virulence factors (adherence, biofilm formation, and secretion of hydrolytic enzymes), swelling their persistence within the host, triggering host cell damage, and finally, resulting in clinical and microbiological failure. Therefore, the increase in the incidence and antifungal resistance of C. glabrata leads to high morbidity and mortality. It has low sensitivity to common antifungal drugs and can rapidly develop resistance to fluconazole. The resistance rate is on the rise. These mechanisms cover all antifungal classes, but mostly the azoles, which are the most commonly used by physicians, in both ambulatory and hospital environments. As long as the various classes of antifungals are being used therapeutically or prophylactically, and sometimes indiscriminately, resistance mechanisms are emerging and the therapeutic solutions becoming narrower. Candida glabrata only grows in the yeast form. So it is lacking a yeast-to-hyphae switch, which is one of the main virulence factors of C. albicans.

A total of 21 C. glabrata arthritis cases have been found available in the PubMed database retrieved by the keyword of “Candida glabrata” and “fungal infection” or “arthritis” [2, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. The mean age at diagnosis was 61 (± SD 14) years, 16 of which (76.19%) are over 50 years. Thirteen cases occurred in the hip, 7 in the knee, 1 in the shoulder, and 1 in the ankle (accompanied by infection of the knee). Fourteen cases had risk factors for fungal septic arthritis, and the main risk factors include systemic disease (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) and/or immunosuppressive therapy in 7 (33.3%) cases, diabetes mellitus in 3 (14.3%), long-term antibiotic use in 3 (14.3%), chronic steroids in 4 (19.1%) cases, and arthroplasty in 18 (85.7%) cases. There were 18 periprosthetic joint infections (12 hip arthroplasties, 5 knee arthroplasties, 1 humeral hemiarthroplasty). Only 3 cases were infected without any implant (1 case was after the meniscectomy, 1 was after the orthotopic liver transplantation, and 1 was primary knee joint infection without previous surgery). Due to increased predisposing factors, the risk of such infections has increased as well [9]. The main clinical manifestations were pain, swelling, fever, and exudation.

The diagnosis of fungal arthritis can often be delayed or neglected due to lack of awareness or negative growth [28]. The value of inflammatory tests such as ESR and CRP in the diagnosis is limited. DNA tests are highly specific and can assist in the identification of the fungus in more expedite ways. The diagnosis can also be made by serology, biopsy, an enzyme immunoassay test and intradermal reaction to histoplasmin. It is not possible to confirm whether the arthritis was indeed caused by contaminated skin or instruments in the arthroscopic procedure. It might as well have been the result of temporary immune compromise caused by the surgical procedure in an already infected but asymptomatic individual. It is also hard to judge whether infection was formed after the first cystectomy although there is no any symptom or sign at that time in this case. The synovial fluid culture is the gold standard of diagnosis and may show positivity in up to 92% [9], but this fungus takes approximately 6 weeks to grow in vitro.

It is difficult to treat the C. glabrata arthritis, and it should be determined by the results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing and mainly includes antifungal drugs and surgical intervention. However, there is no consensus on whether antifungal therapy alone or combined debridement should be conducted when deep fungal infection occurs. The choice of surgical treatment depends on the extent of infection, the exist of implant and the variety of implant. Seventeen cases of infection after arthroplasty were treated by surgical or arthroscopic debridement. The prosthesis of 14 cases was removed, 2 cases were treated with one-stage revision, 10 cases were placed with bone cement spacer, and 5 cases were treated with antibiotic bone cement. The main antibiotics used were gentamicin and vancomycin. Because of the poor thermal stability of antifungal agents such as amphotericin B, they were seldom added to bone cement. The cases infected without any prosthesis were mainly treated with debridement or lavage (one was treated with debridement, one was treated by repeated lavage with saline, and one was treated with drugs merely). One patient lastly underwent amputation. In this case, as Candida osteomyelitis and popliteal fossa abscess were formed, merely arthroscopic debridement was not enough [29]. What is more, the previous debridement, superficial irrigation, and antifungal agents all failed, the articular cartilage was extensively damaged, and thus, we use a two-stage surgical method described above to treat this case since C. glabrata has been reported to be more resistant to antifungal drugs (especially azoles) than other Candida spp. [30]. A medical treatment program should be determined by the results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and it must be made in consultation with infectious disease specialists. The guidelines developed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend that Candida arthritis should be treated for at least 6 weeks with fluconazole at a dosage of 400 mg daily or with a lipid formulation of amphotericin B at a dosage of 3–5 mg/kg daily for at least 2 weeks, followed by fluconazole at a dosage of 400 mg daily. Candida glabrata has varied sensitivity patterns to the newer azoles. It is usually considered to be resistant to fluconazole but is often sensitive to itraconazole, although resistance is becoming a problem in some centers. The presence of an implant caused the production of a Candida biofilm, which limited the action of the antifungal drugs. It seems most proper that echinocandins should be first-line agents, due to their fungicidal activities against Candida species and biofilm produced by Candida strains, as well as their safety profile. The common drugs of choice are amphotericin B (conventional or lipid formulation) and voriconazole [31]. However, amphotericin B has many side effects and may not be useful for long-term therapy. On the other hand, voriconazole has good synovial fluid penetration and excellent bioavailability and is less nephrotoxic than amphotericin B [32]. Although recently in vitro study showed good elution of voriconazole from PMMA, compressive strength of the cement progressively decreases with elution. Since there is no general consensus regarding the type and dose of antifungal agents that can be mixed with cement, we have not used any antifungal agents in the cement spacer [33]. The ideal duration and route of administration of antimicrobial therapy have not been determined. However, most protocols have included 6 weeks of parenteral therapy.

It is obvious that there is no enough experience regarding a proper treatment, with this type of infection. Early diagnosis and choice of appropriate treatment, based on the cultures’ results, along with surgical debridement are of paramount importance. The cure of the infection was achieved in all but 1 case who needed above-knee amputation, and 1 case died from other diseases. Six patients with recurrent infection after initial control were followed up for 3–48 months.

Conclusion

Any case clinically suspected to be caused by fungi should be confirmed by mycological tests. This case report shows once more that C. glabrata-induced infectious arthritis is still very difficult to treat and is a potentially devastating complication. It is of utmost importance to report these cases, since there is no consensus yet of the proper antifungal treatment in IFIs. We should be aware of the possibility of fungal arthritis in receiving therapy with arthroscopy. The antifungal drugs, together with surgical intervention, are the effective therapies for a fungal arthritis. The surgical treatment methods include continuous irrigation, arthroscopy flush, debridement, and removal of prosthesis. But for cases with wide damage of cartilage or formation of osteomyelitis, the therapy of osteotomy of proximal tibia and distal femur, placement of a antibiotic bone cement spacer, then a two-stage arthroplasty, combination with systematic antifungal drugs simultaneously, proved to be safe and effective in clearing the infection (Table 1).

References

Fidel PL Jr, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(1):80–96.

Erami M, Afzali H, Heravi MM, Rezaei-Matehkolaei A, Najafzadeh MJ, Moazeni M, et al. Recurrent arthritis by Candida glabrata, a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Mycopathologia. 2014;177(5–6):291–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-014-9744-6.

Sun L, Zhang L, Wang K, Wang W, Tian M. Fungal osteomyelitis after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a case report with review of the literature. Knee. 2012;19(5):728–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2011.10.007.

Yi C, Yiqin Z, Qi Z, Hui Z, Zheru D, Peiling F, et al. Two-stage primary total knee arthroplasty with well-designed antibiotic-laden cement spacer block for infected osteoarthritic knees: the first case series from China. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2015;16(6):755–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/sur.2014.252.

Hagino T, Ochiai S, Watanabe Y, Senga S, Wako M, Ando T, et al. Complications after arthroscopic knee surgery. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(11):1561–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-014-2054-0.

Martin CT, Pugely AJ, Gao Y, Wolf BR. Risk factors for thirty-day morbidity and mortality following knee arthroscopy: a review of 12,271 patients from the national surgical quality improvement program database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(14):1–10. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.l.01440.

Salzler MJ, Lin A, Miller CD, Herold S, Irrgang JJ, Harner CD. Complications after arthroscopic knee surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):292–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546513510677.

Ross JJ, Saltzman CL, Carling P, Shapiro DS. Pneumococcal septic arthritis: review of 190 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(3):319–27. https://doi.org/10.1086/345954.

Azzam K, Parvizi J, Jungkind D, Hanssen A, Fehring T, Springer B, et al. Microbiological, clinical, and surgical features of fungal prosthetic joint infections: a multi-institutional experience. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(Suppl 6):142–9. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.I.00574.

Acikgoz ZC, Sayli U, Avci S, Dogruel H, Gamberzade S. An extremely uncommon infection: Candida glabrata arthritis after total knee arthroplasty. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34(5):394–6.

Anagnostakos K, Kelm J, Schmitt E, Jung J. Fungal periprosthetic hip and knee joint infections clinical experience with a 2-stage treatment protocol. J Arthroplast. 2012;27(2):293–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2011.04.044.

Bartalesi F, Fallani S, Salomoni E, Marcucci M, Meli M, Pecile P, et al. Candida glabrata prosthetic hip infection. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2012;41(11):500–5.

Cobo F, Rodriguez-Granger J, Lopez EM, Jimenez G, Sampedro A, Aliaga-Martinez L, et al. Candida-induced prosthetic joint infection. A literature review including 72 cases and a case report. Infect Dis (Lond). 2017;49(2):81–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/23744235.2016.1219456.

Darouiche RO, Hamill RJ, Musher DM, Young EJ, Harris RL. Periprosthetic candidal infections following arthroplasty. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(1):89–96.

Dumaine V, Eyrolle L, Baixench MT, Paugam A, Larousserie F, Padoin C, et al. Successful treatment of prosthetic knee Candida glabrata infection with caspofungin combined with flucytosine. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31(4):398–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.12.001.

Fabry K, Verheyden F, Nelen G. Infection of a total knee prosthesis by Candida glabrata: a case report. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71(1):119–21.

Gaston G, Ogden J. Candida glabrata periprosthetic infection: a case report and literature review. J Arthroplast. 2004;19(7):927–30.

Goodman JS, Seibert DG, Reahl GE Jr, Geckler RW. Fungal infection of prosthetic joints: a report of two cases. J Rheumatol. 1983;10(3):494–5.

Hall RL, Frost RM, Vasukutty NL, Minhas H. Candida glabrata: an unusual fungal infection following a total hip replacement. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-006491.

Koutserimpas C, Samonis G, Velivassakis E, Iliopoulou-Kosmadaki S, Kontakis G, Kofteridis DP. Candida glabrata prosthetic joint infection, successfully treated with anidulafungin: a case report and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2018;61(4):266–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12736.

Lejko-Zupanc T, Mozina E, Vrevc F. Caspofungin as treatment for Candida glabrata hip infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;25(3):273–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.01.005.

Nayeri F, Cameron R, Chryssanthou E, Johansson L, Soderstrom C. Candida glabrata prosthesis infection following pyelonephritis and septicaemia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29(6):635–8.

Ramamohan N, Zeineh N, Grigoris P, Butcher I. Candida glabrata infection after total hip arthroplasty. J Infect. 2001;42(1):74–6. https://doi.org/10.1053/jinf.2000.0763.

Selmon GP, Slater RN, Shepperd JA, Wright EP. Successful 1-stage exchange total knee arthroplasty for fungal infection. J Arthroplast. 1998;13(1):114–5.

Skedros JG, Keenan KE, Updike WS, Oliver MR. Failed reverse total shoulder arthroplasty caused by recurrent Candida glabrata infection with prior serratia marcescens coinfection. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2014;2014:142428. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/142428.

Zhu Y, Yue C, Huang Z, Pei F. Candida glabrata infection following total hip arthroplasty: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7(2):352–4. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2013.1420.

Zmierczak H, Goemaere S, Mielants H, Verbruggen G, Veys EM. Candida glabrata arthritis: case report and review of the literature of Candida arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 1999;18(5):406–9.

Kawanabe K, Hayashi H, Miyamoto M, Tamura J, Shimizu M, Nakamura T. Candida septic arthritis of the hip in a young patient without predisposing factors. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(5):734–5.

Gamaletsou MN, Kontoyiannis DP, Sipsas NV, Moriyama B, Alexander E, Roilides E, et al. Candida osteomyelitis: analysis of 207 pediatric and adult cases (1970–2011). Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):1338–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis660.

Pfaller MA, Boyken L, Hollis RJ, Messer SA, Tendolkar S, Diekema DJ. In vitro susceptibilities of clinical isolates of Candida species, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Aspergillus species to itraconazole: global survey of 9,359 isolates tested by clinical and laboratory standards institute broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):3807–10. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.8.3807-3810.2005.

Sili U, Yilmaz M, Ferhanoglu B, Mert A. Candida krusei arthritis in a patient with hematologic malignancy: successful treatment with voriconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):897–8. https://doi.org/10.1086/521253.

Sebastian S, Malhotra R, Pande A, Gautam D, Xess I, Dhawan B. Staged reimplantation of a total hip prosthesis after co-infection with Candida tropicalis and Staphylococcus haemolyticus: a case report. Mycopathologia. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-017-0177-x.

Miller RB, McLaren AC, Pauken C, Clarke HD, McLemore R. Voriconazole is delivered from antifungal-loaded bone cement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):195–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-012-2463-8.

Gumbo T, Isada CM, Muschler GF, Longworth DL. Candida (Torulopsis) glabrata Septic Arthritis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(1):208–209. https://doi.org/10.1086/520160.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethics Approval

This study was proved by the Shanghai Chanzheng Hospital Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent

Informed written consent was obtained from the patient prior to publication of the case details.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Handling Editor: Weida Liu.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Chen, Y., Zhou, Yq. et al. Candida glabrata-Induced Refractory Infectious Arthritis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Mycopathologia 184, 283–293 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-019-00329-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-019-00329-8