Abstract

Digital platforms are becoming critical infrastructures for supporting a variety of innovative services that enhance our everyday lives. These platforms need to offer not only rational services but also ludic or slow services that focus on human pleasure. One important aspect of creating innovative digital platforms is that their concrete requirements and potential opportunities are vague before they are designed. Thus, designing, prototyping and evaluating digital platforms iteratively is essential for refining or customizing them, as knowledge is gradually gained throughout these iterations. However, it is costly to develop prototype platforms and evaluate them with traditional methods. A better tool that can be used to reveal these platforms’ potential opportunities by conceiving them in a simple and rapid way is needed. In this paper, we present our journey to develop nine digital platforms that share collective human sight and hearing with the Human-Material-Pleasure (HMP) annotation method, which is a tool that we use to describe the visually structured annotations of multiple digital platforms based on the annotated portfolio method. The most significant part of the paper presents annotated portfolios based on the HMP annotation method for the nine digital platforms that we develop and shows how these annotated portfolios play an essential role in revealing and exploring the potential opportunities of our platforms during the refinement process. We also discuss how the HMP annotation method is used in the context of exploring the potential opportunities of wearable shape-changing robotic devices; these devices have significantly different characteristics from our digital platforms, which allows for showing insights more objectively by extracting diverse insights from an alternative angle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the last decade, an increasing focus has been placed on digital platforms across a variety of socioeconomic sectors, and transformational developments have occurred in the field of information and communication technologies. Together, these developments are engendering dramatic new opportunities for service innovation, the study of which is both timely and important. Recent advanced digital technologies have dramatically changed our daily lifestyles [70, 73, 93]. A smartphone containing powerful computational capabilities allows us to access information anytime and anywhere. Because phones also have various sensing capabilities, they can retrieve various types of information from the real world. In the near future, we will wear smartphones embedded in glasses, earphones and clothing, and such devices will be used to enhance our bodies’ capabilities [93]. For example, Google Glass [34] provides the capabilities of a mobile phone but is designed as a pair of eyeglasses, and eSense offers the capability to analyze human behavior through earphones [48]. These smart glasses, earphones and clothing illustrate the potential to enhance the capabilities of our eyes and ears.Footnote 1 In particular, the cameras and microphones contained in these devices offer new opportunities, as they can be used by other people as alternative eyes and ears.

Recently, digital platforms used to exploit digital artifacts such as smart wearable devices have become increasingly important to support our everyday activities [46, 52, 73]. Digital platforms represent one category of artifacts, and they offer abstractions or abstract objects that allow for the implementation of diverse innovative services on the platforms. Digital platforms are very complex from both the human perspective and the social perspective. Additionally, these platforms must offer high-level abstractions for developing diverse services. Therefore, to enable the construction of widely available digital platforms, diverse issues should be investigated. The interaction between human issues and platform issues (in particular, from an implementation perspective) is crucial, but both the human side and the platform side are independently designed in the traditional design process. The sociomateriality perspective suggests that human and nonhuman issues should be considered cooperatively at the same level to enable an understanding of social organization in the current technology-oriented society [64, 66, 75, 76]. A lack of adequate tools prevents us from exploring both sides at the same level when designing digital platforms [49]. In particular, we believe that cooperatively identifying the key abstractions of digital platforms and the human experiences triggered by abstraction are significantly influenced by each other.

Over the past several decades, the research on digital technologies has largely focused on rationalistic technological advancements. However, there have been steadily growing concerns about the limitations that such a strong focus places on utility and functionality. In particular, some researchers, especially those in the design-oriented human computer interaction community, have employed a dominantly rational focus that can obscure their efforts regarding how they account for relations between humans and technologies and how technologies shape human experiences in the world [23, 29, 73, 81, 102]. As a result, an interest in expanding this scope beyond utility and functionality has emerged in the research community. New design approaches, such as ludic design [73, 100] and slow design [58, 74], are emerging as alternatives to designing rationalistic focused, productivity-oriented, or goal-driven digital technologies. It is difficult to discuss how to develop innovative digital platforms that offer services beyond those identified by a rationalistic focus. Google has developed Google Street View [3], which is a popular rationalistic service, but this service has been used by artists to create artwork. For example, Jacqui Kenny is a unique travel photographer [94]. It is difficult to predict these innovative use cases during the design phase of new technology without a better tool to explore their potential opportunities.

A subtle philosophical argument against adopting universal standards for conduct in the sciences is presented in Paul Feyerabend’s Against Method [24]. The history of the sciences is replete with examples where a “rationalist” would have made a poor judgment call. He urges that we need to be aware of the limits of all rationalisms, and to ask, “How can we gain knowledge beyond rationalisms? Additionally, how we can document this knowledge?” The seminal works by Donald Schön [85] and Nigel Cross [14] lay the foundations for our understanding that there are diverse ways of interpreting the designs of everyday artifacts. With the recent advances in creative ways of working with innovative digital technologies, the relationship between research and design has been widely discussed [23, 29, 81, 102]. Typically, human-computer interaction researchers engage in the practice of design to make digital artifacts that can be explored in their use contexts and that reflect the new domain use cases and design perspectives revealed through practice, the artifacts themselves, or their use.

A number of proposals have been made on how to gain knowledge through the design of artifacts. These proposals have examined various forms of intermediate knowledge [44], such as annotated portfolios [10], strong concepts [43], research through design [29], concept-driven design [91], practice-driven research [81] and bridging concepts [18]. In particular, Jonas Löwgren emphasizes intermediate knowledge forms, which can be representations of meta-knowledge that guide how to design rather than what to design [69]. William Gaver states that the textual descriptions of artifacts, including any theoretical declarations about them, are considered annotations unrelated to the rationalistic approach [30]. The annotated portfolio method employs a collection of designs, which are represented in an appropriate medium, and these design representations are accompanied by brief annotations. These annotations describe the contexts of these design artifacts to their designers and researchers, and also provide an understanding of the research outcomes, successes and failures at each stage of the design process. Ilpo Koskinen and his colleagues assert that “Good design research is driven by understanding rather than data” [61], and this statement represents the basic motivation for this study’s core proposition: “The use of the annotated portfolio method, as a way for researchers to more deeply understand their research situations, is appropriate to explore the potential opportunities to refine research artifacts”.

In this paper, we present our journey to refine or customize digital platforms by exploiting diverse opportunities. In our project, we developed nine digital platforms that collectively share human eyes and ears, and they were utilized as the portfolio of our project. After developing two of the nine platforms, to explore their potential opportunities, we decided to use the annotated portfolio method to describe the essential properties of the digital platforms. During this process, we found that we needed the annotations to contain additional structured descriptions of the platforms’ exploration opportunities. We employed two different disciplines related to exploration to develop the visually structured annotation method. The first discipline is named sociomateriality, and it deals with humans and materials at the same level. The second discipline is named four pleasures, and it is used for designing the nonfunctional aspects of digital artifacts that lie beyond the rationalist perspective. We developed the human-material-pleasure (MHP) annotation method to incorporate these two disciplines into the annotated portfolio method. Therefore, in this paper, we first introduce an overview of the HMP annotation method (Section 4). Then, we describe our journey of using the HMP annotation method, and we detail our experiences with refining and customizing the nine digital platforms with the proposed method (Section 5). For exploring the effectiveness of our approach, we asked an expert researcher to use the HMP annotation method in his research projects, where we believe that the reproducibility of the validity of the HMP annotation method through multiple projects conducted in diverse different contexts will provide objective evidence for showing the significance of our study (Section 6).

This study makes the following two contributions. First, we propose the use of the HMP annotation method for exploiting and revealing the potential opportunities of digital platforms. The HMP annotation method provides visually structured annotations that can be used to find diverse unexploited issues in designs. The second contribution is that we show our journey of using the HMP annotation method to develop our nine digital platforms that collectively share human eyes and ears. We describe the ways in which we use the HMP annotation method to refine our platforms by exploring their opportunities. The direction of this study is significantly different from those of traditional studies intended to gain rationalistic scientific knowledge, but we believe that this direction is crucial to gain and document knowledge to advance our research scope in accordance with Paul Feyerabend’s proposition.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the background of our study. In Section 3, we provide a portfolio with overviews of our nine digital platforms. Section 4 presents an overview of the HMP annotation method. In Section 5, we detail our experiences with using the HMP annotation method to refine the digital platforms in our portfolio. Section 6 presents the experiences of an expert researcher who works on different types of artifacts with using the HMP annotation method to explore research artifacts. Section 7 describes our reflection of our experiences with the study. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper.

2 Background

This section presents the background of our study. First, we provide an overview of the sharing economy concept and our adaptation of this concept to include the collective sharing of human eyes and ears, as these concepts are the basis of the nine digital platforms in our portfolio. Second, we describe the sociomateriality perspective, which refers to a discipline where technology and human interaction with technology are interlinked such that the two concepts cannot be objectively studied separately due to constitutive entanglement; this concept forms part of the basis of our annotation method. Third, we describe the generative design method and the four-pleasure framework used for designing innovative products and services; these also form part of the basis of our annotation method. Finally, we present an annotated portfolio that can be used as a design tool to represent extracted knowledge regarding products and services, because the annotated portfolio method is used to represent our nine digital platforms.

2.1 Sharing economy and collectively sharing human eyes and ears

Multisided digital platforms, which are collectively called the sharing economy, involve a sprawling range of multisided digital platforms and offline human physical activities such as Airbnb,Footnote 2 a peer-to-peer lodging service, and Uber,Footnote 3 a peer-to-peer transportation network used to share physical goods and logical resources [9, 35, 37]. The sharing economy uses digital technologies to provide individuals, corporations, nonprofits and governments with information that enables the optimization of resources through the redistribution, sharing and reuse of excess physical goods and logical resources [37]. The sharing economy also offers nonprofits new possibilities for innovation and efficiency along with new paradigms to progress from scarcity to abundance [35].

A market economy is essential to the current popular sharing economy platforms as sharing others’ property is necessary to succeed in matchmaking on multisided digital platforms; however, a market-based approach is not essential to a sharing economy because the term “economy” is used in terms of matchmaking on multisided digital platforms [22]. The most essential issue is how better incentives can be designed and chosen to successfully increase matchmaking on multisided digital platforms. There are a variety of ways to offer incentives for matchmaking [22]. Additionally, traditional sharing economies generally involve people’s physical belongings, such as cars, logical resources, or spare time. Investigating the feasibility of sharing other types of physical resources, particularly human bodies, might offer promising opportunities and provide an interesting new direction in which to expand the current scope of the sharing economy because navigating people’s behavior is necessary for accessing specific situations through sharing others’ bodies.

Our digital platforms, which are described in Section 3, focus on collectively sharing physical human body parts, in particular, human eyes and ears, in our case, people’s physical belongings and logical resources are not shared. These platforms allow us to share people’s body parts such as their eyes and ears instead of their physical belongings as in traditional sharing economy platforms. For example, on the CollectiveEyes digital platform [52] and the CollectiveEars digital platform [55], people allow users to collectively share their eyes and ears with very little effort. These platforms construct complex user experiences by integrating multiple times and spaces where diverse people live. The platforms allow their users to access a variety of spaces that other people see and hear; then, these experiences are seamlessly connected and clearly represented by trajectories [6]. To analyze the potential opportunities presented by these platforms, it is essential to investigate various kinds of experiences, such as diverse types of pleasure.

2.2 Actor-network theory (ANT) and Sociomateriality

Actor-network theory (ANT), which originated in the context of science and technology studies and, more broadly, in the context of sociology, is characterized as a constructivist philosophy. Fundamentally, it is not complex, but it offers radical implications: “The social is constructed by virtue of the relations between actors, which can be human or nonhuman and form a network” [64]. This symmetry between human and nonhuman actors is controversial, as it attributes agency to objects as soon as they have a relationship with other actors in a network [92]. Bruno Latour emphasizes that the “social” is not something that can be separated from other disciplines, activities or aspects of life. In an exploration into materiality and artifact design, Verena Fuchsberger and her colleagues have already pointed out the potential of ANT in terms of documenting the designs of artifacts; indeed, they asserted that “ANT would explicitly include the activity of the involved actors into the descriptions, i.e., of materials, designers and users” and “It would provide a common way of describing the design examples and thus facilitate a shared understanding, especially in the materiality discourse.” [28].

Sociomateriality is a theory built upon the intersection of technology and society. It attempts to understand the constitutive entanglement between social and nonhuman entities (Sociomaterialists typically use the term “material” instead of “nonhuman”.) in everyday life. Building on many researchers’ perspectives and thoughts regarding the definition of technology has given birth to debates about technology-in-use and the fundamental concepts of sociomateriality [75, 76]. In developing agential realism, Karen Barad suggests that additional attention needs to be paid to the ways in which meaning and matter are held together [4, 5]. Sociomateriality involves the enactment of a specific set of practices that integrate materiality with institutions, norms, discourses, cultures, and other social phenomena. Since sociomateriality focuses on the relationship between humans and technology, this perspective is useful in terms of investigating the influence of nonhumans on human attitudes and behavior.

Wanda Orlikowski, who is one of inventors of sociomateriality, claims that we should develop a relational ontology that presumes that the social and the material are inherently inseparable. Contrary to her claim, Paul Leonardi talks about agencies that are woven together [65, 66]. Our perspective of sociomateriality is close to his thinking, as he distinguishes between “human agency” and “material agency”; in this way, he does not privilege humans over nonhumans but rather human agency over material agency. He emphasizes the following: “Human agency is typically defined as the ability to form and realize one’s goals [...] [and the] human agency perspective suggests that people’s work is not determined by the technologies they employ”; “Material agency is defined as the capacity for nonhuman entities to act on their own, apart from human intervention. As nonhuman entities, technologies exercise agency through their “performativity””;Footnote 4 and “People who have goals and the capacity to achieve them (human agency) confront a technology that does specific things that are not completely in their control (material agency). In the enactment of their goals, then, people must contend with the material agency of the technology” [65].

2.3 Pleasure and experience in the generative design method

Along with what has been called the third paradigm in the human-computer interaction research field [25, 40], creativity has become central to the approaches of researchers and practitioners in the field. The recent developments in the field of design have required designers to become increasingly aware of their users’ experiences, their users’ emotions, the situation in which an artifact is used, and the relevant social and cultural influences. To extract design insights from the diverse contexts surrounding an artifact’s use, a number of techniques, such as participatory design methods, have emerged to enable extensive explorations of users’ lives. Among these techniques, cultural probes [31] and generative tools [83] involve asking participants to design artifacts that express diverse aspects of the their situations, lives, joys, worries, and more. In a typical case, participants are given a toolkit of words and images and asked to create collages and pictures that express the desirable and undesirable aspects of the contextual situations in which they use certain artifacts. These creations are used to inspire designers and researchers when they make innovative artifacts. The participants also present their creations to each other to inspire the extraction of new ideas. These creations are used to analyze various aspects of users’ attitudes and behaviors involving the examined artifacts.

The pleasures derived from using goods and services stem from the perceived benefits they offer to their users. Pleasure is defined as an experience that humans find enjoyable, positive, or worth seeking; while “experience” is a very broad term that is difficult to define, Marc Hassenzahl provides three considerations that are useful in the context of this study [39]: 1) Experiences are meaningful, personally encountered events; 2) Experiences are constructed as stories that comprise moment-by-moment events, and 3) Experiences emerge from integrating perception, action, motivation, and cognition into an inseparable, meaningful whole. Patrick Jordan outlines four types of pleasure involved in designing goods and services that offer benefits beyond functional efficiency and usability [47]. A way of classifying the different types of pleasure has been proposed by Lionel Tiger. He conducts an extensive study of pleasure and develops a framework for addressing pleasure-related issues, and he outlines this work in some depth in his book “The Pursuit of Pleasure” [95]. As shown below, his framework models four conceptually distinct types of pleasure: physical, social, psychological and ideological pleasure.

-

1.

Physio-Pleasure: Bodily pleasure derived from the senses, including that related to the tactile and olfactory properties of goods and services.

-

2.

Socio-Pleasure: Enjoyment derived from relationships with others, where goods and services may confer social status and identity and may play a role in social situations.

-

3.

Psycho-pleasure: Mental pleasure, including people’s cognitive and emotional reactions to goods and services.

-

4.

Ideo-pleasure: Pleasure involving people’s collective values, which influences people to buy goods and services that express their personal values, including, for example, their concern for the environment or sustainable living.

In consumerist societies, buying, using and displaying goods and services has come to represent a certain type of pleasure. This pleasure principle has to be acknowledged in the development and design of new goods and services. Product semantics is the study of the symbolic qualities of human-made objects in the cognitive and social contexts of their use [62]. The fundamental purpose of this field of study is to treat the form of a designed object as a message and identify possibilities for designers to intervene in the formation process. The term symbolic qualities refers to the psychological, social and cultural contexts in which a good or service exists, thus, these qualities are also considered rather than only considering the physical and physiological functions of a good or service. This theory creates a link between pleasure and the forms of artifacts, which embody their affordances.

As pointed out in Section 1, considering issues that lie beyond the rationalistic or utilitarian perspective is key to revealing potential opportunities to intentionally design user’s experiences with digital artifacts. Our annotation method aims to broaden our design scope by explicitly noting issues related to the pleasurable experiences of human and nonhuman agents to understand the potential opportunities within the related iterative design processes.

2.4 Annotated portfolio

Despite the recent progress that has been made in framing knowledge and finding better ways to communicate knowledge within research communities, an improved understanding of how design can generate new knowledge is necessary, as shown in Section 1. As we embrace more complex domain use cases such as those related to social innovation [16, 68] or the personalized fabrication of digital artifacts to increase their social impact, it becomes essential to explore strategies and methods for understanding how to design digital artifacts [67, 70, 89, 98]. In a museum, a curator arranges diverse pieces of art so that his or her audience can be aware of the essential ideological claims implicitly represented by the pieces by looking at them in the same place and at the same time [21]. This approach seems to be useful for considering the potential opportunities presented by artifacts, especially those presented by digital artifacts, which are highly complex in nature.

William Gaver and John Bowers’s annotated portfolio method provides a way to articulate the new knowledge gained from research-oriented design practice. They assert, “Beyond single artifacts, however, annotated portfolios may serve an even more valuable role as an alternative to more formalized theory in conceptual development and practical guidance for design. If a single design occupied a point in design space, a collection of designs by the same or associated designers – a portfolio – establishes an area in that space. Comparing different individual items can make clear a domain of design, its relevant dimensions, and the designer’s opinion about the relevant places and configurations to adopt on those dimensions.” [30].

The annotated portfolio method provides a means for revealing the resemblances and differences that exist in a collection of artifacts [10]. The method originally involved selecting a collection of artifacts, finding appropriate representations for them and adding brief textual and pictorial annotations to them. The method provides a way in which extracted insights and knowledge can be communicated publicly. William Gaver and John Bowers emphasize that there are many ways to create an annotated portfolio [30]. Some researchers use this method by summarizing the annotations in a body of academic papers [42] or sharing them between group members collaboratively [50]. The method has also been used as a form of reflection to discuss design choices made over time and to critique the progress of successful design ideas [90]. An annotated portfolio of material samples was used in the business model concept used to extract insights for development [78].

The value of learning by experience has been deeply studied within education communities. For example, David Kolb’s experiential learning theory identifies the process by which knowledge is created through the continual transformation and application of experience [60]. As indicated by Cathryn Hall [36], specific annotations can be framed through Kolb’s model, which is presented in four stages: the experience (stage 1) itself is followed by reflection (stage 2), then abstraction (stage 3) of insights, and finally experimentation (stage 4) involving what has been learned. on is employed to specify the details of the annotation. The annotation portfolio method spans two intermediate stages, reflection and abstraction, with reflection playing an important role in the annotation method as the designer is immersed in the user experience when designing reflectively using tacit knowledge [79, 85] and creative knowledge [14]. Following this reflection, abstraction was employed to specify the details of the annotation.

There are several previous studies that use the annotated portfolio method [17, 26, 63, 71]. In [17], the concept of the original annotated portfolio method is extended to include designs for new domains. In [41], they do this by creating an annotated portfolio that treats such research through design (RtD) artifact inquiries as postphenomenological inquiries, as according to John Zimmerman and Jodi Forlizzi [102], RtD is a discipline that has expanded design practices and processes to include general new knowledge. The concept of Design Exposès [26] intentionally lacks a designated “value” layer in the reflection part because the focus of this idea is more on the “utility” aspect of objects.

Our annotation method is influenced by David Kolb’s model, which is used to gain knowledge reflectively through an iterative design process to refine or customize digital platforms and to document their core abstract properties using annotations. By reviewing these annotations, designers and researchers can clearly identify the key knowledge extracted from their designs and use this knowledge for the refinement of their digital platforms. Our annotation method incorporates the perspective of sociomateriality to discuss the relationship between humans and nonhumans, explicitly making the gaps between them obvious to explore platforms’ potential opportunities beyond the rationalistic perspective from multiple angles involving pleasure.

3 A portfolio of digital platforms for collectively sharing eyes and ears

4 Human-material-pleasure annotation method

First, this section presents the early stages of our journey of using the Human-Material-Pleasure (HMP) annotation method. Then, we provide an overview of the method and the iterative design process that we used to refine and customize the digital artifacts.

4.1 Experiences with building knowledge through CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars

To clarify the new knowledge gained from the design and research of these nine digital platforms over almost three years, we decided to identify and assemble the respective insights corresponding to each platform and organize them in annotated portfolios. By this phase, we had developed CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars and conducted some user studies to extract insights revealing their potential opportunities. The poster style typically used in computer science conference presentations was adopted to present the related annotations to represent knowledge gained from the studies, as shown in Fig. 2 (larger images are found in Appendix 3.). The purpose of these annotations was to provide a concrete overview of the CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars platforms, including not only their aims and basic functions but also the remarkable insights gained through their designs, observations of using the working prototypes, and the interviews that identified the most important concerns regarding their designs, interaction technologies, or use cases [52, 55].

The experiment described in [52] adopted especially immersive scenarios in which the participants felt that they used CollectiveEyes exceptionally well. Thus, the experiment successfully extracted the diverse merits and demerits from the perspective of the user experience. On the other hand, the experiment could not extract enough insights to explore novel use cases involving collectively sharing human eyes and ears. We thought that ordinary participants may think only of use cases from the narrow perspective of platform users; thus, it is not easy to obtain interesting novel use cases from them. Additionally, the participants tended to mainly consider useful purposes that could apply to daily life because these issues were familiar to most of them. Moreover, the ordinary participants involved did not suggest different interaction methods or using the platform for different purposes, and they did not consider using the platforms in the context of their other activities. One of the reasons for this is that the experiment offered immersive experiences, so it was difficult for the participants to imagine other situations in which they could use the platform during the experiment. Some insights, which were provided by a speculative designer’s expert analysis intended to extract the potential opportunities of CollectiveEyes in terms of new technologies and emerging social situations, were also reported in [52]. However, these extracted opportunities may significantly depend on the skill of this expert.

Thus, the above discussions reveal that a tool for broadening artifacts’ designed purposes, widening the scope of an experiment’s participants or even broadening the perspectives of speculative design experts is essential for exploring more opportunities. Most ordinary people are experts about their daily lives, but they are not able to identify and document the diverse issues affecting them. However, if a proper tool is offered to trigger their unconscious experiences, they may have the chance to explore additional diverse issues in their daily lives through their experiences. In particular, such a tool can help digital platform designers explore the hidden opportunities in the designs of their platforms, allowing them to broaden their perspectives and see these opportunities from various different angles.

4.2 An overview of the human-material-pleasure annotation method

The concept of values is a critical tool used to understand various aspects of digital artifacts such as digital platforms’ influence on people’s experiences [46, 97]. As conceptualized in Fig. 3, human sight and hearing are materialized as sharable abstract objects on our digital platforms, where the objects have inherent abstract values, enabling people to access these objects according to their values. This leads to the two concepts that we need to understand when considering values in the context of these platforms. The first concept relates to how a user who uses the platforms experiences concrete or abstract values through other people’s sight and hearing, and the second relates to how other people’s sight and hearing influence a user’s experience. The related values are essentially determined by the design of the embodied values, not the intrinsic values [97], so carefully thinking about both factors is essential for designing values that make a user feel that materialized human sight and hearing is meaningful.

According to the first concept, the values of human sight and hearing can be investigated from the human perspective by understanding each user’s goals for using the platforms and constructing his/her experience in terms of the definition presented in [39]. Therefore, first, identifying the domain use cases of the platforms is essential, and then their possible values can be investigated in terms of achieving the goal of a satisfactory user experience. According to the second concept, the values of human sight and hearing can be investigated from a nonhuman perspective by understanding the influence of nonhumans, in this case, digital platforms, on a user. Digital platforms consist of a set of abstract objects that can be used to build a variety of services or interactions with users [49], and the abstract objects construct the affordances of the nonhumans (in our case, digital platforms), which determine their interactions with their users or the construction of the services they offer; Paul Leonardi asserted that affordances are constructed through human and nonhuman (material) agencies [66]. As presented in [11, 13, 15, 88], the nonhuman perspective provides a promising way to expand our current perspective, broadening them to exploit the hidden opportunities of digital artifacts. The annotated portfolio described in Section 2.4 seems to be a promising tool that could be used to document the values that represent the abstract qualities of digital platforms according to these two concepts, revealing the potential opportunities of these digital platforms and enabling us to refine them based on the revealed opportunities.

To investigate the abstract qualitative aspects of the digital platforms, our annotation method for documenting annotated portfolios, named the human-material-pleasure (HMP) annotation method, involves choosing two disciplines to represent the human and nonhuman aspects of the platforms. The first discipline, sociomateriality, which was explained in Section 2.2, makes us think of the influences of the digital platforms on people and their surroundings from both human and nonhuman (material) perspectives. Figure 4 presents a basic approach for annotating the platforms based on this discipline, where the two perspectives are explicitly represented as domain and interaction perspectives and the annotations classified according to these perspectives are called domain annotations and interaction annotations. The domain annotations with “Domain” labels are used to identify the digital platforms’ domain use cases that address the goals of their users. The interaction annotations with “Interaction” labels are annotations that correspond to the interaction methods offered by the digital platforms that can be used to communicate with users or offer services. Our use of these “Domain” and “Interaction” annotations is greatly inspired by the work of [17], whose aim is to discuss a new domain of digital artifacts. One of the most important contributions of the HMP annotation method is the explicit introduction of both of the perspectives in the visually structural annotation method.

The second discipline is the four-pleasure framework shown in Section 2.3. The four-pleasure framework makes it possible to classify the aforementioned abstract values into four categories: physio-, psycho-, socio-, and ideo-pleasure. Based on the domain and interaction annotations, we identify the potential values of the digital platforms. Then, these values are categorized according to the four types of pleasure and described through annotations called pleasure annotations. Each pleasure annotation is also labeled either human or material. The annotations labeled human are called human annotations, and those that are labeled material are called material annotations; we use the term human/material annotation to refer to both types of annotations.

Figure 5 shows a template that visually represents annotations based on the HMP annotation method. In explaining this template, we use the term “artifact” rather than “digital platform” in this subsection because this annotation method can be used for diverse digital artifacts corresponding to a broader category than that of digital platforms. Each artifact has its own type of annotation according to the template, so a single portfolio would contain multiple annotations for each of its digital artifacts. At the top left of each annotation, the name of the corresponding artifact is shown. The red interaction annotation contains a list of annotations categorized according to the interaction methods used in the corresponding artifact, and the green domain annotation contains a list of annotations categorized according to the potential domain use cases of users. The background of each artifact’s annotation also contains several visual images of the artifact. The pleasure annotation contains a list of annotations for each of the four pleasures and assigns different colors to them to make them visually obvious. Each material annotation belonging to the four pleasures is assigned a label, namely, “MPh”, “MPs”, “MSo” or “MId”, which stand for “Material Physio-pleasure”, “Material Psycho-pleasure”, “Material Socio-pleasure”, and “Material Ideo-pleasure”, respectively. Similarly, each human annotation is assigned a label, namely, “HPs”, “HPh”, “HSo” or “HId”, which stand for “Human Physio-pleasure”, “Human Psycho-pleasure”, “Human Socio-pleasure”, and “Human Ideo-pleasure”, respectively.

The classification shown in Table 1 provides basic explanations of each of the types of pleasure from both the human and material perspectives.Footnote 5 Each pleasure annotation labeled “human” basically represents the physical and mental experiences offered by the artifact to users, and each annotation labeled “material” represents the core abstract objects that construct the affordances of the digital platforms that enable services to be built. In the following section, we provide a brief summary of the meaning of each classification in the table.

“HPh: physio-pleasure” represents people’s essential physical activities that are incorporated into an artifact’s HMP annotations. “HPs:psycho-pleasure”, “HSo:socio-pleasure” and “HId:ideo-pleasure” represent individual, communal and collective user experiences, respectively, and these experiences represent the core human factors offered by the artifact. The use of “HId:ideo-pleasure” rather than “HPs:psycho-pleasure” or “HSo:socio-pleasure” as a user experience’s annotation indicates that the experience is focused on collective human experiences.

“MPh: physio-pleasure” refers to abstract objects that are implemented as core abstractions to virtualize the physical objects in an artifact and construct an affordance that provides various services and user interactions.Footnote 6 “MPs:psycho-pleasure”, “MSo:socio-pleasure” and “MId:ideo-pleasure” refer to abstract objects that construct affordances to influence individual, communal or collective user experiences. The difference between “MPs:psycho-pleasure” and “MSo:socio-pleasure” is that “MPs:psycho-pleasure” focuses on an artifact’s affordances that influence individuals and “MSo:socio-pleasure” focuses on the affordances that influence people communally. “MId:ideo-pleasure” specifically describes the core ideological concepts related to designing affordances that influence people collectively, and these concepts are related to the ideological goals identified in the domain use cases of an artifact.

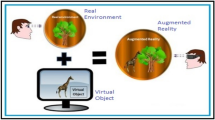

“MPh: physio-pleasure” is different from the other material annotations because this annotation represents virtual objects related to the physical world. The essential characteristics of this annotation can be explained as virtuality incorporated into the real world. In [46, 82], the authors present various examples of digital/physical hybrid objects that do not actually exist, but people feel that they truly exist in the real world. This concept is useful when considering logical objects that are not seen in the real world, such as the institution mechanism explained in [46]. These digital/physical hybrid objects are considered core affordances that can be used to build digital platforms. In this paper, we limit the scope of our annotation to represent human sight and hearing, but the potential power of this annotation can be exploited in the future, extending the use of the HMP annotation method to more diverse settings.

4.3 Iterative design according to the HMP annotation method

Figure 6 shows the iterative design process that we use to refine our digital platforms with the HMP annotation method. During the design process, we first investigate the platforms’ essential properties in terms of domain and interaction annotations. Basically, a list of domain annotations is created by understanding the goals of the platforms, and then the derived human annotations are investigated by examining the potential values in the related user experiences. A list of interaction annotations is created by investigating the interaction methods that could possibly be used to communicate with users or to offer services, and then their derived material annotations are used to specify the abstract objects needed to implement the interaction methods for users and services. One important aspect of the HMP annotation method is that we can identify potential pleasures by comparing them to other respective pleasures. During the design process, we can also compare the annotations of different digital platforms, where the aspect is the most important in annotated portfolios. This exploration may help identify unnoticed potential opportunities of the digital platforms. Then, we can rethink the domain and interaction annotations by revealing these unnoticed pleasures. Finally, we reinvestigate the pleasure annotations based on the reexamined domain and interaction annotations. During the refinement process, we mainly focus on the interaction annotations, and during the customization and refinement process, we mainly focus on the domain annotations.

Figure 7 shows an example of the design process that we use to develop the digital platforms in our portfolio. We first design CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars through several iterations. After these platforms are designed and evaluated, we develop their annotations using the HMP annotation method. Then, CollectiveEyes is refined to Ambient CollectiveEyes to incorporate diverse presentation methods as new interaction methods, and CollectiveEyes is also refined to Gamified CollectiveEyes by identifying the values in shared human sight. CollectiveEars is refined to Artful CollectiveEars by exploring the interaction method of theme channels. During the refinement process, by considering the pleasure annotations, we identify additional potential opportunities, which are presented in the next section. The remaining digital platforms are customized versions of CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars, and they each offer a single specialized service developed through examining the domain annotations. By focusing on the aspect of wellbeing, CollectiveEyes is customized to create Gathering Happy Moments, and by focusing on the aspect of social watching, this platform is customized to form Citizen Science with Dancing. By focusing on the aspect of hearing sound as music, CollectiveEars is customized to create Mindful Speaker, and by focusing on the aspect of nonhuman agency, it was customized to create Ambient Sounds Memory. In the next section, we provide a detailed explanation of how the platforms are customized based on the HMP annotation method.

5 Iterative refinement or customization with annotations based on the HMP annotation method as design case studies

This section provides more details about our experiences with refining or customizing the digital platforms. In our journey, we argued that the crafting and studying of digital platforms should be framed as engaging in philosophy through artifacts. We did this by creating an annotated portfolio of research through design (RtD) artifacts [33]. This section presents our true experiences of working with the HMP annotation method.Footnote 7 We believe that our documented experiences validate the proposed method’s ability to enable explorations of the potential opportunities of digital platforms.

5.1 CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars

Figure 8 presents the annotations based on the HMP annotation method for CollectiveEyes, and Fig. 9 shows the annotations for CollectiveEars. The annotations “Human Sight as a Material” and “Human Sight is a Material” were the most essential core material annotations representing physio-pleasure that can be used to construct the affordance of human sight and hearing, and these annotations were replicated in all the other digital platforms in our portfolio. The annotations “View Classification with Keywords/Location” in CollectiveEyes and “Sound Classification with Situations” in CollectiveEars were the core material annotations representing physio-pleasure that could be used to construct the affordance of basic user interactions that classify human sight and hearing according to the classification policy selected by a user, and these annotations were refined in each platform to incorporate the new opportunities found in the other platforms.

In CollectiveEyes, the core human annotations were “Experiencing Diverse Human Sight”, which represented psycho-pleasure, and “Experiencing Diverse Cultures”, which represented socio-pleasure; in CollectiveEars, the core human annotations were “Experiencing Diverse Human Hearing”, which represented psycho-pleasure, and “Experiencing Diverse Culture”, which represented socio-pleasure. These annotations were replicated in the other platforms so that leitmotif user experiences could be offered. Additionally, in CollectiveEyes, the core material annotations were “Diverse View Presentation”, which represented psycho-pleasure and “Diverse Human Sight Collection”, which represented socio-pleasure; in CollectiveEars, the core material annotations were “Diverse Sound Presentation”, which represented psycho-pleasure, and “Human Hearing as a Material”, which represented socio-pleasure. These annotations were replicated in the other platforms, but refining the properties of these annotations according to the respective platforms was essential in the design process. Identifying core material annotations was the most important part of the design process because these material annotations made the core abstract properties of the platforms stand out among complex platforms.

The annotations of CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars were created after exploring their potential opportunities, as shown in [52, 55]. In this early phase, as explained in Section 4.1, we were just interested in the potential of using others’ eyes and ears. Then, we started to investigate the potential domain use cases of this concept, and many annotations were created during this investigation. While investigating the annotations, we especially focused on the aesthetic aspects identified in through our previous work and literature reviews [73, 93]. These aspects appeared more explicitly in later platforms and became an important leitmotif of the platforms, although they were implicitly represented in the “World Landscape” and “Soundscape” domain annotations of CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars.

The human annotations “Watching the World” and “Hearing the World” were labeled ideo-pleasure because these annotations strongly influence humans’ ability to think. Our interviews with the participants of the experiments regarding CollectiveEyes revealed that the possibility of enhancing people’s thinking abilities is important [52]; thus, we introduced “Thinking about the World” and “Diverse and Reflective Thinking” as domain annotations. The domain use cases are explicitly presented in the pleasure annotations as “Enhancing Thinking Abilities” and “Defamiliarization”, which represent ideo-pleasure. The reason that we categorized “Defamiliarization” as a material annotation is that we believed that “Defamiliarization” was the platform’s affordance for ideologically influencing humans collectively. Additionally, these annotations became core leitmotifs of our platforms related to exploring opportunities that redefine human sight and hearing. For example, in Gamified CollectiveEyes and Artful CollectiveEars, “Valuing Human Sight” and “Valuing Human Hearing” appeared as new interaction annotations related to making people more conscious of their current sight and hearing. This investigation strongly influenced the expansion of these platforms’ new opportunities.

Investigating the interactive annotations allowed us to explore various new opportunities offered by the platforms. The “Virtual Traveling” domain annotation of CollectiveEyes represented certain typical domain use cases. This domain annotation introduced the human annotation “Experiencing Others”, which represented psycho-pleasure through the interaction annotation “Body Ownership”. This approach is similar to that of KinecDrone [45], which controls a drone’s field of vision through a user’s body gesture. This case clearly shows an example in which introducing a new interaction method expands the scope of a domain use case to offer a new user experience. Similarly, the “World Sound Listening” domain annotation of CollectiveEars was an important domain use case allowing a person to experience “Hearing the World”, which was a human annotation representing ideo-pleasure. Regarding interaction annotations, the theme channel interaction method of CollectiveEars was one of the most important interaction methods of our digital platforms. The use of interaction method was first proposed for CollectiveEars, and the method was used as a core interaction method to refine our platforms. In particular, the material annotation “Sound Classification with Situations”, which represents physio-pleasure, was a key interface of CollectiveEars that used theme channels. We refined this annotation in other platforms by enhancing their theme channels.

Regarding the annotations shown in Figs. 8 and 9, the following four points, which focus on demonstrating the merits that we found while creating the annotations, also need to be made. The first point is that focusing on the four pleasures offered an opportunity to consider hidden aspects in our design. For example, while in the first stages of developing the platforms, we did not strongly focus on the socio-pleasures that could be offered through them. This finding made us aware of the need to exploit socio-pleasure during the refinement process, and these experiences were actually reflected in the design of Ambient CollectiveEyes and Artful CollectiveEars.

The second point is that there was a need to compare the annotations among the platforms. For example, in developing CollectiveEyes, we focused on the human annotation “Experiencing Others”, which is designed to offer the feeling of becoming others. On the other hand, in CollectiveEars, we did not focus on this annotation. While investigating the annotation, we realized that it would be hard to achieve in CollectiveEars, but we found that the human annotation “Feeling Others” in Artful CollectiveEars offered an opportunity to offer the experience of feeling what others felt; thus, the refinement revealed a new social opportunity.

The third point is that CollectiveEars has a few domain annotations, which means that we found a few domain use cases during the beginning stages of designing CollectiveEars. After designing CollectiveEyes, we thought that it would be interesting to develop a digital platform that was focused on only collectively sharing human hearing. Therefore, CollectiveEars was developed by extracting interaction methods from created scenarios in certain situations [55]. A small number of domain annotations indicated that we had the opportunity to investigate more pleasures and find new domain use cases for CollectiveEars. We especially focused on ideo-pleasure to find new possibilities, and this investigation was reflected in the refined design of Artful CollectiveEars, as shown later.

The fourth point is that there was no physio-pleasure from the human perspective in the annotations reviewed thus far. CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars were used in virtual spaces, so a user did not need to physically move to access others’ current sight and hearing. However, incorporating physio-pleasure could offer promising opportunities for enhancing human wellbeing. Physical movement is a key part of a healthy society. By offering the location information of others’ current sight and hearing, the platforms could encourage users to consider going to see or hear the things that others are currently seeing and hearing if the locations are not too far from them.

5.2 Ambient CollectiveEyes

Ambient CollectiveEyes was designed by refining CollectiveEyes, and the highlights of this platform were the two interaction annotations “The Agency of Sight” and “Nonhuman View”, which were developed through the refinement process. Figure 10 shows the annotations of Ambient CollectiveEyes.

The first refinement made was related to redefining human sight based on “The Agency of Sight” annotation through virtualizing human sight as a material. When a user accessed other people’s current fields of vision, CollectiveEyes presented these fields of vision to the user without presenting any information about the people who were offering those views. However, this meant that the user did not feel the agency of the other people who were offering their current fields of vision. Therefore, accessing others’ current fields of vision was the same as watching videos from a camera. In Ambient CollectiveEyes, a person’s current emotions were represented in his/her field of vision to convey his/her agency. A number of people who shared the same field of vision could also view it ambiently in their current field of vision, enabling them to enjoy the feeling of collective sight.

The second refinement was based on the “Nonhuman View” annotation. By using materialized human sight, CollectiveEyes could easily combine other views, such as views from cameras in cities or views from the perspective of animals, fish or even insects. Such views from nonhumans offered new perspectives to people, so they had an increased possibility of enhancing their thinking through the defamiliarization effect; this annotation was listed among the annotations of CollectiveEyes, but its effect was strengthened in Ambient CollectiveEyes by the addition of nonhuman perspectives. Thus, we could investigate new potential opportunities related to the “Diverse View Presentation” material annotation. To incorporate nonhuman visual views, we introduced a new interaction method called ambient photomontage [56], which was related to the “Diverse View Presentation” annotation. This method offered a new viewing function that superimposed multiple people’s current fields of vision on the scene that a user was viewing. Additionally, this method offered a timescape option that spatially represented time-dependent views. The ambient photomontage method was also essential to refining human sight capabilities, as it layered diverse views from both humans and nonhumans on a user’s current field of vision, thus defamiliarizing human sight. The material annotation “Defamiliarization” was carried over from CollectiveEyes, but its effect was enhanced, enabling us to incorporate the material annotation “Redefinition of Human Sight”, which represented ideo-pleasure.

In Ambient CollectiveEyes, a new domain annotation named “Collective Seeing” was introduced by investigating a new opportunity of CollectiveEars (Similarly, Collective Hearing was incorporated into Artful CollectiveEars.). This addition allowed Ambient CollectiveEyes to incorporate more socio-pleasures like the human annotation “Feeling Others”, and the more ideological perspective of “Seeing Collectively” was added as an ideo-pleasure. For example, explicitly incorporating values allowed a user to feel the sentiments of others. Additionally, a user could continue to access the sight of one specific person, and that view could be shared by multiple users. Thus, a user could see the same sights as others, thus human sight could become collective. Additionally, by focusing on the material annotations “Diverse View Presentation” from the perspective of physio-pleasure, human sight could be presented on physical screens such as [101] instead of 3D virtual spaces.

5.3 Gamified CollectiveEyes

Gamified CollectiveEyes was also designed by refining CollectiveEyes. In this refinement, the new main focus of the platform was to investigate the potential of the interaction annotation “Valuing Human Sight” in terms of incorporating gamification strategies into CollectiveEyes. Figure 11 presents the annotations of Gamified CollectiveEyes.

To increase the number of human fields of vision offered, Gamified CollectiveEyes increased people’s motivation to offer their current fields of vision to others. To incorporate human motivation, we focused on the material annotation “Diverse Human Sight Collection”. To access other people’s current fields of vision, a user needed to specify the values of his/her current view. In Gamified CollectiveEyes, the value of a user’s current view was assigned by the user, and as presented later, the interaction annotation “Valuing Human Sight” became a key factor of exploring the new opportunities of the platforms, where assigning respective values to people’s current views was done according to their judgment. We first focused on a gamification strategy to encourage people to tag the views that they were offering with the corresponding values. Gamified CollectiveEyes incorporated game mechanics that were intended to facilitate social engagement to encourage competition with others to collect more human fields of vision. A leaderboard for comparing users’ scores was introduced as an abstract object, which was related to the material annotation “Social Engagement”, and this feature offered an affordance that enhanced socio-pleasure. To allow access to human fields of vision according to each user’s expectations, the platform needed to collect a large number of views. Additionally, ensure the success of Gamified CollectiveEyes, its participants needed to offer the fields of vision that the platform needed to satisfy various users’ preferences related to human fields of vision. This gamification strategy required people to physically move to find and offer the fields of vision that the platform needed to increase their scores on the leaderboard. This case provided an example of explicitly incorporating physio-pleasure from the human perspective, which is related to the human annotation “Moving Physically”.

The interaction annotation “Valuing Human Sight” also offered new opportunities to refine the platforms’ affordances for with user interaction. While designing Gamified CollectiveEyes, we introduced the theme channel concept from CollectiveEars and the opportunity to refine human sight capabilities from Ambient CollectiveEyes. In Gamified CollectiveEyes, refined theme channels called object-based theme channels and value-based theme channels were introduced. This was represented as the material annotation “View Classification with Things”. The object-based theme channel could explicitly specify things that appeared in people’s current fields of vision. The value-based theme channel could access specific human fields of vision through selecting people’s current views according to abstract values. This was represented as the material annotation “View Classification with Values”. The difference between the keyword or location searches used in CollectiveEyes and the theme channels used in Gamified CollectiveEyes was that the keyword or location function allowed users to attach any keywords or locations to their current views, so the number of channels would change in an ad hoc way according to the number of keywords or locations being used. On the other hand, the object-based and value-based theme channels each comprised a fixed number of channels, which were defined in the platform. This approach to classify the human fields of vison was important because all the human fields of vision were classified according to a fixed number of categories, which made the matchmaking process between a theme in the theme channel and a user’s value tags easy. The theme channel interaction method was very powerful because a user could specify abstract themes such as an aesthetic theme. Additionally, since the description of a theme could be abstract in Gamified CollectiveEyes, a user could find serendipitous fields of vision because the ambiguity allowed by an abstract description could include unexpected views [54].

Gamified CollectiveEyes adopted conscious sight through allowing users to tag their current fields of vision with values, thus increasing users’ opportunities to enhance their thinking abilities [54]; indeed, by explicitly tagging their views, people become aware of what they are currently seeing and consider the appropriate values for their current views, as shown in Section 5.1. The human annotation “Seeing Consciously”, which represents ideo-pleasure, was added to Gamified CollectiveEyes to reflect this investigation.

5.4 Artful CollectiveEars

Artful CollectiveEars was designed by refining CollectiveEars. Figure 12 shows the annotations of Artful CollectiveEars. The refinement of CollectiveEars to Artful Collective Ears was mainly focused on the investigation of the potential opportunities of the theme channel system introduced in CollectiveEars.

During the refinement process, we especially focused on the concept of art as briefly mentioned in Section 5.1, where we specified the domain annotation “Art”. In this investigation, our focus was to explore the flexibility of the theme channel system. In Artful CollectiveEars, six theme channels were defined to select the sounds that would be presented to a user; these channels were based on our investigation of incorporating artful user experiences. The material annotation “Sound Classification with Values” was obtained by refining the material annotation “Sound Classification with Situations” of CollectiveEars through adapting the theme channel system to offer only natural sounds.

The domain annotation “Collective Hearing” was proposed through another investigation of the opportunities offered by the theme channel system. We focused on the human annotation “Feeling Others”, which represented socio-pleasure in a similar way as Ambient CollectiveEyes represented this aspect, namely, users would know that someone had explicitly assigned the sounds that they were hearing to a specified theme channel, and they could imagine the current feelings of the people who were offering these sounds. The domain annotation “Collective Hearing” enhanced the artful aspect of Artful CollectiveEars because users could hear the same sounds as other people; however, these sounds could be changed by anyone, and users could listen to these continuously changing natural sounds like music. Thus, we considered the above features the platform’s nonfunctional properties, and the related annotation was labeled ideo-pleasure from a material perspective.

As we had done in the cases of Ambient CollectiveEyes and Gamified CollectiveEyes, we investigated the possibility of redefining human capabilities with Artful CollectiveEars. People usually hear their surroundings unconsciously. Only when sounds contain strong stimuli, such as those that indicate risk or arouse curiosity, do people listen consciously. Therefore, people are usually not aware of a variety of issues in the real world due to this unconscious hearing. However, if a user needs to assign classification tags to the sounds that he/she is currently hearing, he/she becomes more conscious of the sounds currently surrounding him/her. In particular, if a user wants to offer better audio to Artful CollectiveEyes, he/she needs to be careful to find good sounds near him/her. Adding the material annotation “Human Hearing Redefinition”, which represents ideo-pleasure and was adopted from Gamified CollectiveEyes, offered us the opportunity to investigate a new design possibility.

The human ideo-pleasure annotations in Artful CollectiveEars may offer new opportunities if the annotations usually labeled socio-pleasure are reconsidered. For example, the human annotation “Hearing Collectively”, which was labeled an ideo-pleasure in the platform, was based on the assumption that sounds are collectively heard by everyone because, at this point, we assumed that Artful CollectiveEars offered artful user experiences to many audiences. However, if sounds are delivered in a physical space, the people who are in that space can hear the same sounds, and they can enjoy the sounds together. This investigation allowed us to explore additional opportunities to apply this idea in a new platform called Mindful Speaker.

5.5 Reflection on iterative design process with HMP annotations

In this subsection, we divide our journey, which was described in the previous subsections and Appendix 2, into four categories based on our experiences with iteratively designing the abovementioned digital platforms according to the HMP annotation method. The first category is related to examining the four pleasures one by one to investigate the role of each pleasure in each platform. In particular, after creating each platform’s annotations, we examined the pleasure annotation that did not clearly appear to be included in the platform’s annotations. For example, after creating the pleasure annotations for CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars, we reinvestigated the role of socio-pleasure in these platforms; thus, we explored the role of socio-pleasure in Ambient CollectiveEyes and Artful CollectiveEars as shown in Sections 5.2 and 5.4.

The second category concerns the relationships among the different pleasure annotations. After specifying each pleasure annotation, we sometimes considered which pleasure was appropriate for the annotation. In particular, when we focused on user experiences, we considered whether each experience was more suitable for an individual, a communal or a collective setting. Usually, we first focused on the psycho-pleasure entailed in the user experiences, but after that, if we found that the annotation could be used for a communal user experience, we shifted to examine the socio-pleasure of that annotation; similarly, if the annotation could be used for a collective user experience, we shifted to examine the ideo-pleasure of the annotation. For example, when developing Gathering Happy Moments, the pleasure annotations were useful in considering the balance needed to classify positive user experiences into individual, communal or collective categories. The balance was significantly important to offering better positive memories while taking into account diverse user experiences, as shown in Section B.1. As shown in Section B.2, we discussed how reconsidering each pleasure offered new possibilities in the case of Citizen Science with Dancing. Additionally, we discussed how physical space influenced the pleasures offered by Mindful Speaker in Section B.4.

The third category concerns the human and the material labels for each pleasure annotation. We mainly considered an annotation to be a human annotation if it was related to the user experience, and we labeled it as a material annotation if it was related to the abstract objects comprising the affordances for users or services. Exploring new human annotations offered opportunities to investigate new domain annotations, and investigating material annotations offered opportunities to investigate new affordances that could be offered on the platforms. Additionally, focusing on the material perspective allowed us to explore the nonhuman perspective. For example, when developing Ambient CollectiveEyes, we explored the possibility of incorporating nonhuman views to offer views that were more diverse than those that humans see, as shown in Section 5.2. Similarly, when designing Ambient Sounds Memory, we ascribed agency to physical objects in the context of decorating a living room, as presented in Section B.3.

The fourth category is related to investigating the pleasure annotations of the different platforms. By comparing the annotations among the different platforms, we were able to find new opportunities related to each platform. In particular, by comparing the platforms’ human/material annotations, it was possible to find potential opportunities that allowed us to exploit alternative interaction methods or novel user experiences. Additionally, by comparing the pleasure annotations of different artifacts, it was possible to find more potential opportunities related to the platforms. For example, by comparing the annotations of CollectiveEyes and CollectiveEars, we found new opportunities for CollectiveEars, as shown in Section 5.1 Additionally, as shown in Section 5.3, Gamified CollectiveEyes was influenced by CollectiveEars through our investigation of the classification of human views through the theme channel.

6 Using the HMP annotation method in a wearable robotic device project

In the previous section, we mainly focused on how the HMP annotation method is used to refine digital platforms that allow human eyes and ears to be shared. In contrast, this section focuses on how the HMP annotation method can be used in the context of another type of digital artifact, wearable shape-changing robotic devices. These artifacts have significantly different characteristics from those of our digital platforms, which have concrete, physical characteristics. The purpose of this section is to discuss a researcher who did not know the HMP annotation method before analyzing the opportunities presented by the artifacts developed in his project, and we investigate how he felt when using the HMP annotation method and how he used the method in his project to create annotations of the artifacts that he had developed. The investigation reveals additional insights regarding the HMP annotation method from an alternative angle. Also, the insights described in this section make the validation of the HMP annotation method more objective through the multiple angles to use the method conducted in significantly different contexts.

We hired a postdoctoral researcher and asked him create annotations using the HMP annotation method for the artifacts that he had created in his past projects. The reason that we chose the person is that he was working on wearable shape-changing robotic devices that were very different from our digital platforms. As shown in Fig. 13, he has developed three artifacts. Orochi is a snake-like wearable robot that can be used as additional human arms [1]. HapticSnakes is a robotic feedback device for virtual reality (VR) applications [2]. WeARable includes augmented reality (AR) technologies, which are used to control wearable robots [96]. Initially, we gave an approximately one-hour lecture comprising an overview of the HMP annotation method and its background. Then, we provided some example annotations from our digital platforms as concrete examples. We gave him approximately one month to evaluate his artifacts with the HMP annotation method. One month later, we had another meeting to discuss the final annotations that he had created for his artifacts and interviewed him to document his experiences using the HMP annotation method to explore new potential opportunities for his artifacts.

In the following subsections, we first report this individual’s experiences using the HMP annotation method to create annotations for his artifacts. We are especially interested in how he was able to reveal the previously unexploited aspects of his projects and find new opportunities by using the HMP annotation method. This aspect is very interesting because he developed these artifacts through his doctoral research projects, so we thought that he had already explored various opportunities before preparing his final doctoral dissertation. Finally, we present our thoughts on the annotated portfolio that he created, providing additional insights into the HMP annotation method.

6.1 Experience with using the HMP annotation method

In our interview with the researcher, he first pointed out some difficulties that he encountered while investigating his artifacts using the HMP annotation method. The first difficulty he pointed out was that it was not easy to find a proper starting point to document the annotations. He said, “It would be helpful to have a guide on how to start creating annotations.” The second difficulty was that it was hard to find new ideas for improving the existing artifacts. He said, “The approach is more suitable for building a new artifact based on the insights found while investigating the annotations of existing artifacts.” In particular, he pointed out that considering the socio-pleasures of his existing artifacts became a source of new ideas for creating new artifacts. The third difficulty was that he needed to spend much time considering the assignment of the respective pleasures to his annotations. He said, “I needed to reconsider my assignments of the pleasures to the respective annotations, and I went back and forth several times.” From his statements, we found that we need a good guideline to help establish a process to create the annotations. However, we should be careful how the guideline specifies the details of the process because ambiguity is an essential resource for finding diverse opportunities, as pointed out in [32]. In particular, the researcher claimed that he needed to spend time investigating the pleasures, but this time-consuming process is essential to finding sufficient opportunities. He also pointed out that he was not familiar with investigating socio-pleasure and ideo-pleasure in his studies, but we believe that these unfamiliar pleasures were good resources with which to find more opportunities.

During our interview with this researcher, we found that he did not understand pleasure from a material perspective very well. We thought that this was mainly due to the nature of his artifacts. His artifacts have concrete, physical forms. In contrast, our digital platforms are logical infrastructures, where psycho-pleasure is represented through material annotations; thus, this issue is caused by his artifacts’ physical forms. Therefore, we thought that he had difficulty clearly distinguishing between the affordances of physio-pleasure and those of psycho-pleasure in his artifacts. Additionally, wearable devices are usually used by only one person, so it is difficult to imagine affordances related to socio-pleasure and ideo-pleasure in the context of his artifacts. However, as pointed out in Section 6.3, this issue also becomes a resource that reveals unnoticed potential opportunities. Therefore, we understood that the teaching aspect of our proposed method is a very essential issue, and this should be a future research direction.

6.2 Exploring potential opportunities through annotated portfolios

From our interview with the researcher, we found that he had extracted several insights through his analysis based on the HMP annotation method. In this investigation, he mainly found new insights related to human annotations that represent socio-pleasure. He said, “If a robot is trustworthy, it can boost the self-esteem of its users, decrease their dependence on others for unfamiliar physical activities, and alter their lifestyles to focus only on what matters.” Additionally, he pointed out, “A robot can be used as a partner to reduce loneliness, both physically and nonphysically.”, and “A robot can be used as an advisor to train new skills, to learn how to operate something, etc. In this context, the robot takes the lead and a user follows.” These opinions of his provided strong evidence that the HMP annotation method was useful in his investigation.