Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to develop a novel multidimensional typology of free-to-play gamers, based on the theory of consumption values and to test whether these types of gamers differ in their premium content consumer purchasing behavior. The study uses a survey of 839 Czech free-to-play gamers, where the players’ values are tested across 27 items. Factor analysis is used to identify 6 different factors (values) influencing the gamers, which are then used as variables in a cluster analysis to identify 5 distinct gamer types. Results show that each identified gamer type differs not only in gaming (length of gameplay) but also in purchasing behavior (current purchase and future purchase intention, average monthly spend). One new gamer type, previously unidentified in the literature, has been identified (the enthusiasts), alongside the development of additional details for three of the more “standard” game types (economic aesthetes, identification seekers and killers). Gamers from the Czech Republic are used in the sample, limiting the generalizability of the study. The research complements existing gamer typologies by developing an empirically supported view of free-to-play gamers that is based on value, which results in the identification of one new gamer type. We also extend consumption values theory by identifying the multi-dimensional impact of value characteristics on purchase behavior in a context of emerging commercial and social importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The video games (VG) industry continues to grow, and it is estimated that in 2025 the global gaming market will reach 268.8bn USD annually, up from 178bn USD in 2021 [8]. In 2019 players around the world spent more than 145bn USD on computer, video and mobile games, far exceeding global box office earnings (42.5bn USD) and worldwide music revenues (20.2bn USD) [57]. Global revenue in the VG segment is projected to reach 175.10bn USD in 2022 and to show an annual growth rate of 8.17% (CAGR 2022–2026), resulting in a projected market volume of 239.70bn USD by 2026, with the number of users expected to amount to 3,197.7 m by 2026, much of which is driven by its largest segment (Mobile Games) with a 2022 market volume of 124.90bn USD [65].

A significant part of this growth is based on the increasing popularity of free-to-play games, which generated 17bn USD in 2018 just on Personal Computers (PCs) [12], compared to 8bn USD spent on traditional pay-to-play games. Free-to-play is the dominant monetization model for mobile and PC gaming and is also quickly changing how console games are monetized with 74% and 159.3bn USD of games revenue being based on in-game purchases [75]. Free-to-play games have increased in market revenue, from 58.8bn USD in 2018 to 75.6bn USD in 2021 [9]. In 2020, the worldwide leading free-to-play game titles by revenue were (all in USD): Honour of Kings 2.45bn, Peacekeeper Elite 2.32bn, Roblox 2.29bn, Free Fire 2.13bn, Pokemon Go 1.92bn, League of Legends 1.75bn, Candy Crush Saga 1.66bn [11]. Although still not considered part of the mainstream, blockchain/NFT games are also growing in popularity, with the following having high play counts in 2022: Alien Worlds (1.16 m), Axie Infinity (677k), Splinterlands (604k), Bomb Vrypto (561k), Sunflower Farmers (476k), Upland (333k), DeFi Kingdoms (230k) [13]. Mobile gaming is also growing at 4.4% year on year and is more than half of the global games market [76]. In 2021, smartphone games generated approximately 81.5bn USD in annual revenue, accounting for 52% of the global gaming market during the measured period, with console games ranking second with 50.4bn USD in global revenue [10].

Free-to-play games are free to acquire, but players are encouraged to buy additional (premium) content during play [4]. This content takes various forms; some being purely aesthetic (player character or game item skins), others taking the form of additional content (e.g., new maps, functions or game modes), and some which provide paying players with a significant advantage over non-paying players (e.g., stronger items, experience bonuses, reduced time limits etc.). Although there is extant literature that looks at purchasing behavior in the VG industry, it tends to focus on the wider scope of virtual goods [23], typologies across the wider gaming field [72], or specific genres such as massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) [32].

Despite its growing commercial importance, research into free-to-play games has received significantly less academic attention, e.g., a search of the ProQuest database using “free to play games” as a search term identified only 121 journal results, although there is an upward trend in numbers of publications that suggests a developing interest in the area. This paper uses the theory of consumption values to develop an empirically supported typology of free-to-play gamers based on the concept of value and then analyzes their purchasing behavior. To understand the possible motivations of gamers to purchase premium content, two research questions were distilled: (1) are there distinct groups of free-to-play gamers, and (2), do these groups vary in their premium content purchasing behavior? Addressing these questions contributes to our further understanding of purchasing behavior in the context of free-to-play games, as a specific value-based typology is developed, and also to the development of consumption values theory by identifying the multi-dimensional impact of value characteristics on purchase behavior in the context of emerging commercial and social importance. The companies in the field (mainly game developers) could also benefit from knowing what types of gamers generally play free-to-play games, what is their purchasing behavior and the consumption values that may influence their behavior.

The literature review establishes the context of the research by looking at the free-to-play games market and revenue model and existing gamer typologies, before setting out the theoretical basis of consumption values theory, its application in related areas, and how the hypotheses were developed. This is followed by a methods section, describing the data collection and analysis of the survey responses. The findings section starts with a factor analysis showing the different influences on buyer behavior, before a cluster analysis groups these into a typology specific to free-to-play games. The implications of these findings for both academia and practice are then discussed, and future research opportunities and limitations are identified in the final section of the work.

2 Literature review

2.1 Context - free-to-play revenue model

While there is a lack of consistent terminology used, free games are those with no charge to play and can be distinguished from “free-to-play” games, in which the base game is free but there is also some sort of premium (additional) content that can generate revenue [64]. Such premium content can be defined as the additional, paid “goods” purchased within the game, although this is not necessarily limited to free-to-play games and has been labeled “virtual goods” [23]. These individual purchases of premium content take the form of a series of “microtransactions” that occur during various times when consumers engage with a VG [7] and this model is often called “freemium” [38]. In-game currency that can be purchased for real-world currency may also be offered and this tends to be one-way in nature, meaning it can only be purchased from in-game vendors and not traded with other players, or back for real-world money. When a game offers premium content that involves the purchase of in-game benefits over non-paying players (more lives, better items etc.), it is often labeled as “pay to win” [4]. In addition to these in-game purchases, there are newer monetization models based on subscriptions, in which players make regular payments to access additional in-game content and features during set subscription periods [22].

Due to the huge financial success of free-to-play games on mobile platforms [28], premium content microtransactions are increasingly being designed into AAA games (with higher development and marketing budgets) by traditional pay-to-play game publishers, such as Electronic Arts or Ubisoft [41]. While these games traditionally featured additional extras called expansion packs or DLCs (downloadable content), many of these games (e.g., sports game series such as FIFA) now also feature elements usually seen in free-to-play games, such as virtual currency purchases. This has led to controversy among game developers, players and video game critics [2], with some 22% of gamers reporting dissatisfaction with the pay-to-win approach [56].

2.2 Gamer typologies

The development of specific typologies that segment and differentiate between types of consumers is an important aspect of consumer marketing research, e.g., Lilly and Nelson [40] segment the fad-buyer market, Fransen et al. [18] generate a typology of consumer strategies for resisting advertising and Angell et al. [5] categorize a range of older grocery shoppers. A number of broad approaches to dividing markets can be used, e.g., based on demographics, behavioral or psychological variables, such as values, attitudes and personality traits [59] and it is within the latter’s domain that this research is positioned. In the VG industry, Jimenez et al. [33] identify that: “…it is crucial to segment gamers so as to design customized strategies and increase player retention (Fu et al., 2017), promote loyalty (Sheu et al., 2009) and understand playing behavior patterns (Drachen et al., 2009)”. The requirement for a deeper understanding of marketing knowledge in novel and popular industries, such as VGs, has also been noted [50] and this research contributes to this research agenda.

One of the earliest attempts at developing a gamer typology is Bartle’s categorization of MUD (Multiple User Dungeons) players [6]. This study differentiates gamer types by their behavioral attitudes within the game as follows: achievers (get scores as fast as possible or to pass the levels to achieve their goal to be successful), explorers (understand how processes in the game world work), socializers (intended to interact with other individuals) and killers (kill other players and enemies in a fast and violent way). A study by Park Associates [44] used 17 attitude items to generate six different player types: power gamers (live and breathe through the online game climate), occasional gamers (preferring puzzles and board games and who do not spend so much money and effort to play games), incidental gamers (play games when they get bored), social gamers (use games as a way of communicating with other people and leisure gamers (consider games a serious hobby and dormant gamers (cannot find enough opportunity to play games).

A number of later typologies have used various segmentation approaches and a useful summary can be found in Sezgin [61]. For example, gameplayer age has been used as a variable in Griffiths et al. [20] in comparing adolescent and adult gamers in online gaming and, from an in-game demographics perspective, Jansz and Tanis [31] identify different clan memberships. Behavioral studies in the field have also shown differences between casual and hardcore gamers [30]. Kallio et al. [36] develop a more behaviorally oriented approach to segmenting gamers, first splitting them into three main groups according to gaming intensity, sociability and types of games played (social, casual and committed), which are then further divided into three additional categories per game type played, e.g., for social games, these are: “Gaming with kids”, “Gaming with mates” and “Gaming for company”, to create nine different player segments. Lopez & Tucker [42] empirically tested gamer types by examining a player’s physical behavior when playing a game, as well as their perception of the game elements, reshaping the original types as socializer, free spirit, achiever, disruptor and player.

Of interest to our research are a number of psychologically and motivationally based studies. Schuurman et al. [60] identified four different player types based on eleven motivational factors, ranging in motivation levels from overall convinced, convinced competitive, and escapist to passtime gamers. Fullerton [19] used personality traits to generate a number of gamer types: Competitors (perfectionists), explorers (adventurous), collectors (arrangers), achievers (success-based), jokers (fun), artists (design and creativity), directors (guiders), storytellers (creating worlds) and performers (presenters). Götzenbrucker and Köhl’s [21] longitudinal study analyzed the effects of lifestyles, habits and media on game behavior and found that significant defining moments in the player’s lives (e.g., new employment) would decrease the duration of their gameplaying. Xu et al. [77] examined gamer motivation (what the player thinks about the game), behavior (what the player does during the game) and effect (the social impact of the player on the rest of the player group). They identify five different types of players: achievers (regular goals that are focused on improving individual progress and personal performance), active buddies (create small groups of close friends, social experience seekers (socializing and making changes to their external representations in the game environment), team players (focused on group belongingness, group achievement, group rankings and improving the performance of the group members) and freeloaders (interested in game beginnings, but interest reduces over time). Vahlo et al. [73] examined digital game preferences by identifying the game dynamics of 700 digital games, and also the gamer’s desire to play games with specific types of dynamics as a complementary approach for motivations to play. Tseng’s [70] motivation-based study, where gamers are split between their “need for conquering” and “need for exploration” and into aggressive, social, and inactive gamers and Nacke et al. [51], who use the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator in combination with a player’s neurobiological gameplay motivations to identify seven-player archetypes (seeker, survivor, daredevil, mastermind, conqueror, socializer and achiever). Jimenez et al. [33] use the Big-Five personality factors to split gamers into three clusters: Analysts, Socializers and Sentinels and Marczewski [49] also uses these factors to identify: socializers (motivated by relational connections among players), free spirits (exhibiting autonomy), achievers (attempting to master the game), philanthropists (help others and make positive contributions), players (win and be rewarded), disruptors (adopt a strong sense of change by disrupting the game system or influencing other players).

The extant typology-based studies tend to look at differentiating gamers according to how they play games based on personality traits or motivational factors. Whilst this is of course a useful endeavor and one which has provided a solid platform for future studies, from a commercial perspective, a focus on purchasing behavior is also needed. Bringing in the concept of ‘value’ generates an evaluative component that is the learned, socially-endorsed beliefs, whereas personality aspects are relatively innate dispositions [54]. The theory of consumption values allows for further exploration of the motivation for consumption behavior, as perceived attribute importance could reflect consumer motivations in purchase choice [63]. It provides a balanced approach because it comprises both intrinsic and extrinsic elements for investigating users’ consumption-related behavior [3]. Work such as Frank et al. [17] generates a typology of virtual goods users in FPS (First Person Shooters) games, relating types with purchase intention and found that some types (aesthetes and adventurers) are more likely than others (critics) to purchase premium content while linking types to demographic characteristics such as age and employment. However, the relative simplicity of some of the extant psychological studies in the wider gamer typology, coupled with a lack of research into free-to-play games, suggests empirical research based on a stronger theoretical foundation is needed to encompass the complex drivers behind gameplay is needed to reflect the growing commercial and social importance of the VG industry. According to Hanner and Zarnekow [25], existing models of predicting purchase behavior from other similar domains do not function well in free-to-play games and our research contributes to this effort. In line with the extant literature, we note that our focus is on purchase intentions and that a separate study would be needed to capture gamer spend data.

2.3 Theory of consumption

To provide a robust theoretical underpinning for our research and in line with suggestions for future research found in Tuunanen & Hamari [72], we propose a multidimensional typology based on Sheth et al’s [63] theory of consumption values. We deploy this theory in a similar way to Mäntymäki & Salo [48], who examine virtual consumption based on developmental psychology and Ho & Wu [27], who use it to analyze purchasing intent in two specific types of online games. The theory states that consumers form positive attitudes and make purchase decisions according to evaluations of multiple value components (i.e., functional, social, emotional, epistemic, and conditional) and that these are possible factors that motivate consumers’ purchases in the future or enhance their intention to use or purchase a product or service [69]. This theory has been used to understand user behavior in the context of hedonic technologies [3, 71], in settings such as intention to purchase digital items in online social media communities [37], and intention to play [43]. The interrelationship between motivation, behavior and value is a complex one, so we follow Gao et al. [74], who propose that values are possible factors that either motivate consumers’ purchases in the future or enhance their purchase intention. The theory is based on consumer psychology and has been expanded on by later studies, e.g. Sweeney & Soutar [66]. Using this perspective, consumer choice can be seen as a function of several consumption values, which make different contributions to any choice situation and are independent of each other. Context specificity in the relative importance of the value components has also been noted [69] and our research provides this specificity for free-to-play games. Aspects of some of these typologies have been used to inform the development of the questionnaire statements and are discussed in the method section of the paper. Our review shows that there is a need to develop a systematic, theoretically, and empirically underpinned typology of free-to-play gamers and has led to the distillation of the first research question: (RQ1) are there distinct groups of free-to-play gamers? As far as we are aware, our research is novel in using consumption theory to generate distinct typologies.

2.4 Purchase intentions

Having used a solid theoretical base to develop a core free-to-play gamer typology, we now turn towards developing a series of hypotheses to more fully explore RQ2, i.e., do these groups vary in their premium content purchasing behavior? To provide a more structured means of addressing the interrelationships between the two research questions, we have developed a series of hypotheses to test whether different clusters (types) of gamers diverge in their premium content purchase behavior.

Consumption theory has been used in different studies of games and consumer purchasing intentions. Shang et al. [62] show that social and emotional values influence the premium content (e.g., decorative items) buying intention of virtual world inhabitants and Kim et al. [37] show that emotional and social values are key elements in increasing a player’s intention to purchase virtual goods. Interestingly, functional values are not directly related to the purchase intention, but their effect is mediated through the self-expression variable. Ho & Wu [27] propose a stronger and direct relationship between the functional value and purchase intent, which is even more evident for users of role-playing games, as aesthetics (part of the emotional value), are an important factor for these types of games. Mäntymäki & Salo [48] describe additional purchasing value, namely money, which is an evaluation of the aggregate benefits over the costs of purchase and also claim that social, functional, epistemic and emotional values are key to the users’ purchase intention. Furthermore, those values are very often not independent, but closely interrelated (such as the social and emotional values). Hamari & Keronen [23] provide a comprehensive meta-analysis of the reasons for purchasing virtual goods, exploring relations among variables with convincing cumulative sample sizes ranging from 639 to 8,045. They conclude that attitude towards purchasing, defined as “[an] own opinion on how positive or negative purchasing virtual goods is” [23], is the key variable influencing a gamer’s purchase intention. Other factors identified include self-presentation, immersion in the game (flow), network size and subjective norms. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study pairs the typology of gamers with their purchasing behavior within video games and this has resulted in the development of the following hypotheses:

-

H1: There are differences in past premium content purchases among the clusters of gamers.

-

H2: There are differences in future purchase intention among the clusters of gamers.

2.5 Purchase behavior – actual spend and immersion

Hamari & Keronen [23] show that increasing freemium service quality does increase sales of premium services via the increased willingness to use the freemium service, however, there is less understanding of what exactly influences how much free-to-play gamers spend on premium content.

-

H3: There are differences in average monthly spend on premium content among the clusters of gamers.

In a free-to-play setting, Lin & Sun [39] conclude that gamers’ immersion might be limited by constant decisions about whether to buy certain in-game items. Similarly, a study of mobile games, which generally tend to be free-to-play, found that user loyalty (the will to continuously play and recommend certain games) is a key mediating determinant of the purchase of premium content and loyalty is in itself influenced by a player’s playfulness (enjoyment of the game), reward and access flexibility [28]. Furthermore, there are significant differences between the paying and non-paying groups of mobile game users, both in their attitudes towards future purchases, e.g., price is influential amongst non-paying users, while playfulness and reward are more influential in paying. Park and Lee [53] use the theory of consumption values to study the value of purchasing virtual items in free-to-play games and, using structural modeling, they find that character competency (defined by increasing character level, getting more points and increasing power), enjoyment, visual authority (adding style and fashion items to the character, being more noticed by others) and monetary value form the integrated value of purchasing game item construct, which then positively influences the purchasing intention. This literature has been used to generate the final hypothesis of the paper:

-

H4: There are differences in the frequency of gameplay among the clusters of gamers.

3 Methodology

We adopted a quantitative approach, using an online questionnaire, to develop a typology of gamers and a deeper understanding of their purchase behavior. While some research applies qualitative approaches to the same issue [4, 7], we aim to develop a clear segmentation of gamers based on their values towards premium content and free-to-play games in general. To develop such a segmentation, factor and cluster analyses were used (similar to [17]) for the development of the typology, followed by statistical testing to find out whether the different types of gamers differ in their purchasing behavior. These quantitative analysis techniques have been used to research consumer behavior in different fields, e.g., Hande et al. [24] used factor analysis to identify behavioral segments in the mobile phone market and Paul and Rana [55] used both factor and cluster analysis in the organic food sector.

3.1 Variables

Having previously explained our definition and framing of free-to-play games and virtual goods, the main items (and independent variables) of our questionnaire were 27 statements about gamer opinions of free-to-play games and their value drivers in purchasing virtual goods. These statements were adapted from papers utilizing similar theoretical and/or methodological approaches and which were available at the time the instrument was put together (in the Autumn of 2017). These papers were Frank et al. [17] (items regarding premium content functions and visual characteristics), Ho & Wu [27] (gamer’s overall satisfaction, character identification and purchase intention), and Hamari & Keronen [23] (social influence, perceived value, self-presentation). These statements are presented in detail in Appendix 1, but an example item is: “The goals of the character become my own goals” with an expression of agreement using a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 = “Fully agree” to 5 = “Fully disagree”, although, for the subsequential cluster analysis, the scales were reverted for easier interpretation.

Subsequently, various variables were used as dependent variables for analyzing the hypotheses. For H1 and H2, past premium content purchase (measured as a binary variable with “yes” and “no” as categories) and future premium content purchase intention (measured on the same scale as the 27 independent variables) were used respectively. For H3, gamers’ average monthly spend on premium content in CZK was measured (measured as an ordinal variable with “1-100 CZK”, “101–500 CZK”, “501–1000 CZK”, “1001–5000 CZK”, and “more than 5000 CZK” as categories). Finally, for H4, frequency of free-to-play gameplay was used (again ordinal variable, with “daily”, “more than two times a week”, “once a week”, “monthly”, and “less often” as categories).

The validity of the questionnaire was checked by showing it to five industry and one marketing research expert, which resulted in altering the text for some of the questions to make them easier to understand.

3.2 Data collection

The data was collected from October 2017 to January 2018 in the Czech gaming community, whose market is the 51st largest in the world based on revenues (151 m USD), or the 30th largest in spend by population [52]. In line with Frank et al. [17], we used the non-probability sampling technique of judgmental sampling [46] and put a link to the survey on several Czech free-to-play gaming forums and social media (Facebook) pages, as gamers tend to form coherent communities [54]. The forums and pages were both on general gaming (e.g., forum Doupe.cz; Facebook pages Gaming Community CZ/SK and Gaming CZ/SK), but also for specific genres of games (World of Tanks CZ/SK; Fortnite CZ/SK). We collected data from 896 respondents in total and 839 responses were used after eliminating incomplete questionnaires. This sample size is sufficient for both factor and cluster analysis [3] and our dataset is larger than that in similar studies by Frank et al. [17] (98 respondents), Ho & Wu [27] (523 respondents) and Jimenéz et al. [33] (511 respondents based in Spain). The respondents were also asked about their purchasing behavior – frequency and usual monthly spend on free-to-play games to ensure that we could identify different gaming and purchasing behavior across the different segments. Further questions included the free-to-play titles played and demographic questions, such as their age, income, economic status and gender, to allow us to develop deeper insights into the different categories of the typology.

4 Data analysis

To develop a typology of gamers based on their purchasing behavior, we used (1) exploratory factor analysis to reduce the 27 items to a more manageable number of factors and (2) cluster analysis to obtain a segmentation of the respondents. The reliability of the instrument was tested using Cronbach’s alpha with reliable results (α = 0.85). The external validity of the new typology was tested using Pearson’s Chi-Square and Fisher’s exact tests in IBM Statistics 24 software and Monte Carlo PCA for Factor analysis software was used for the parallel analysis. This ensured a robust approach to addressing the research questions which were to identify distinct groups of free-to-play gamers and then assess the differences in their premium content purchasing behavior.

4.1 Factor analysis

We used exploratory factor analysis to uncover latent factors, as our research items are based on consumer values theory, there is no sufficient theoretical or empirical base to allow for the use of confirmatory factor analysis. We chose the Principal Factor Axis (PFA) method of factor extraction and, the selection of rotation method. 11 items with factor loading less than 0.5 were eliminated (items no. 1, 2, 7, 8, 11, 12, 17, 24, 25, 26 and 27) and no cross-loadings (items that load at more than 0.32 on two or more factors) were found. To avoid the errors of over or under factoring seen in most standard methods of factor number selection (Kaizer rule and Scree plots), we followed the steps identified by Fabrigar et al. [15]. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.778, which is acceptable [29] and well above the recommended value of 0.6. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant with χ2 (120) = 4118.79; p < 0.05. These indicators support our use of factor analysis to analyze our data. As mentioned in Section 3, the optimal number of factors was determined as 6 by both Kaizer rule and parallel analysis. The factors were labeled based on loaded items (based on [46]), previous research in the field, e.g., [7, 17, 27] and the theory of consumer values [63] where applicable (Table 1).

The first factor consists of three variables that relate to a gamer’s Social interactions. The three loadings show that gamers with high composite scores in this factor are influenced by friends, streamers and newsletters or banners, thus adhering to the original definition of this consumption value by Sheth et al. [63], where value comes from association with others. The Functional factor comprises three items that relate to in-game bonuses or the advantages of purchasing virtual goods, or those that give the player new items such as equipment or maps, in line with how Ho & Wu [27] and Frank et al. [17] envision this value. The Identification factor contains two items highlighting the player’s relationship to their game character. While not part of the original set of consumption values by Sheth et al. [63], identification has been seen as an important factor in game enjoyment and premium content purchase [27]. The Economic factor relates to virtual goods pricing with two items, while the Quality factor consists of three items dealing with the aesthetics of the premium content, its standards and sufficiency of the offer, and these two factors could be linked to the expanded consumption values (e.g., Sweeney & Soutar [66]). The Hedonic factor comprises three items relating to the visuals of the game character, the player’s self-expression to others and exclusively buying virtual goods that only change visual aspects. Hedonic values could be seen as a more specific variation of the Sheth et al. [63] emotional value and are often used in other research [17, 27]. These factors/items are summarized in Table 1 with corresponding values of Cronbach’s alpha for the items.

4.2 Cluster analysis

After discovering the underlying constructs in our items with the exploratory factor analysis, we used cluster analysis to establish a typology of free-to-play gamers [49] with composite factor values for each respondent as variables. As those variables are continuous, we can use many different clustering methods and distance measures and there is no need to standardize the values. We used the hierarchical method of clustering to determine the ideal number of clusters and the k-means method to assign cases into clusters.

To test stability, we divided the sample into two halves and repeated the analysis on each and changed the order of the data for non-hierarchical clustering, generating very similar results. External validity was achieved by comparing the types of gamers on variables that were not a part of the factor nor cluster analysis (frequency and amounts of premium content purchase, types of games played, frequency of gameplay). We also used standard hypothesis testing procedures to test the external validity mentioned in the previous subsection. For the nominal and ordinal data, we used Pearson’s Chi-Square test [46]. Some of the data violate the assumptions of the test (the expected counts in the contingency table are less than 5) and so Fisher’s exact test was used instead. Due to computational difficulties, it was necessary to use Monte Carlo approximation in some cases [16] and one-way ANOVA test was used to test the effect of cluster membership on the interval variable of future purchase intention (results of the tests are presented in Section 4.3).

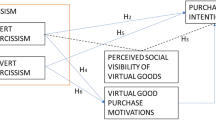

After distributing our original 16 items into the six new factors, we performed the cluster analysis, which allowed us to fully address RQ1, in identifying distinct groups of free-to-play gamers. Five clusters were chosen based on the agglomeration schedule and dendrogram. Due to relatively small differences in the schedule, three to six clusters were considered, but the five clusters solution provided the best basis for interpretation. K-means clustering was performed using these clusters and the final cluster centers as well as the group sizes (percentage of cases in each cluster), are shown in Table 2 and graphically in Fig. 1. Relative cluster sizes were similar, which therefore meets substantiality criteria [46]. Clusters were named based on the final cluster centers, which are themselves based on composite factor scores and, where possible, these were informed by the cluster names from existing gamer typologies.

The first cluster, Economic aesthetes, into which slightly over 20% of gamers fall, focuses mostly on economic (seeking deals and reasonable prices) and hedonic (e.g., game character skins) factors while disregarding the functional factor. These gamers do not buy virtual goods for the possible advantages over non-paying players, but for their hedonic (such as the skin of the game character, enabling one’s self-expression) pleasures. Furthermore, these players tend to focus solely on themselves, with no interest in others, as suggested by the relatively low values of the social factor. Identification seekers are somewhat similar to economic aesthetes in their focus on hedonic factors, however, the main values for this group are identification and establishing strong bonds with their game character where the character’s goals become that of the gamer. The other factors are rated around average (values around 0). This cluster also represents slightly over 20% of free-to-play gamers. The killers, inspired by Bartle’s [6] typology of MUD (Multiple User Dungeons) players, do not prioritize socializing with other players, identification with their character and economic or quality aspects of the virtual goods, and also disregard the hedonistic factor. However, they have the second-highest composite score in the functional factor, suggesting these players view gaming as a means to an end, i.e., to be the best at the game they are playing. This is the largest cluster in terms of relative frequency at 27.18% of gamers. The negativists, representing almost 16% of gamers, have negative composite scores across all factors and the lowest composite scores in four of the six factors (social, economic, quality and hedonic). In contrast to the negativists, enthusiasts (16.2% of gamers) show positive scores in all composites, with five (social, functional, quality, economic and hedonic) being higher than any other cluster. High values of social and functional factors would suggest that these players are relatively similar to Bartle’s [6] explorers, but this cluster also values the hedonic and overall quality of the virtual goods. It could be suggested that this group is more likely to purchase virtual goods than the others.

4.3 Purchasing behavior of the player types

Having clustered the gamer types, we now turn to address RQ2: do the groups of players (set up using the cluster analysis) vary in terms of their purchasing behavior? The external validity of the proposed typology of free-to-play gamers is tested based on variables not included in the factor analysis. The variables include a gamer’s past purchasing behavior (measured as a dichotomic yes/no) and in the future (on a five-point Likert scale), average monthly spend (on a five-point ordinal scale), as well as their general gaming characteristics (frequency of gameplay measured on a five-point ordinal scale). For the nominal and ordinal variables, Pearson’s chi-square test was used to assess the statistical differences among cluster membership. For the interval scale on future purchases, ANOVA was used.

The first variable to assess the validity of the clusters is relatively simple, in which we asked the gamers whether they purchase premium content at all (H1). As seen in Table 3, there are differences among the clusters, with negativists being far less likely to purchase premium content than the other gamer types. Conversely, enthusiasts, comprising gamers with highly positive factor loadings, have by far the highest ratio of premium content purchases (79.4%). Killers also show a relatively high ratio (72.8%), while identification seekers and economic aesthetes are relatively similar at 60.5% and 56.2% respectively.

Results of the chi-square test are significant with χ²(4, N = 839) = 78.462, p < 0.01, Cramer’s V = 0.326. Therefore, we reject the null hypothesis – there are differences in premium content purchases among the clusters of gamers, with effect size (Cramer’s V) indicating a large association between the variables.

We then analyzed the future purchase intention (measured on an ascending five-point Likert scale, means in Table 3) based on the gamer type (H2) and a one-way between subjects ANOVA was conducted to compare the effects of cluster membership on future purchase intention. There was a significant effect between at least two clusters (F(4, 834) = 75.16, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.265), and we therefore reject the null hypothesis. Tukey’s HSD test for multiple comparisons (full Table 7 in Appendix 2) found that the mean value of future purchase intention was significantly different between all the pairs of clusters except for the killers and identification seekers. In line with the results of the previous test, we see that the enthusiasts have by far the highest intention to purchase premium content in the future (M = 3.67, SD = 1.09), contrasting with the negativists who report very low values (M = 1.57, SD = 0.88). This further strengthens the enthusiast’s segment as the most important for VG developers. In the other three segments, identification seekers (2.78, SD = 1.1) and killers (2.54, SD = 1.01) have relatively similar future purchase intentions, followed by the economic aesthetes (2.2, SD = 1.11).

Next, we focused on the average amount spent on premium content per month (H3) and only respondents who confirmed that they purchased premium content were asked this question (n = 513) and the relative frequencies are presented in Table 4. Looking at those who actually spend, a spend of between 101 and 500 CZK (approximately 4–20 EUR) is the most typical across all segments. However, there are significant differences between the segments: enthusiasts are the most likely to spend over 500 CZK per month with over one-third (33.9%) of gamers in the higher categories of spend. Conversely, only a small number of the negativists purchase any premium content (29.9%), and 2.7% of them spend more than 500 CZK per month. 1.3% of all respondents admitted to spending more than 5000 CZK (200 EUR) per month on premium content and these high-spending customers are generally called “whales” by industry insiders [34].

Fisher’s exact test was used to test the hypothesis (H3), as the contingency table violates the assumptions of the standard Chi-square test, with results being significant (p = 0 < 0.001). Therefore, we reject the null hypothesis – there are differences in average monthly spend on premium content among the clusters of gamers.

The frequency of gameplay is the first variable assessed as part of gaming behavior (H4). Gamers tend to play free-to-play games either daily or at least more than twice a week (Table 5). For identification seekers, killers and enthusiasts, daily play is the most frequent and almost 70% of negativists still play free-to-play games at least twice a week, despite their negative attitudes. Results of the chi-square test are significant with χ²(16, N = 839) = 34.8.09, p < 0.01, Cramer’s V = 0.102. Therefore, we reject the null hypothesis – there are differences in the frequency of gameplay among the clusters of gamers, with medium effect sizes indicated by Cramer’s V.

5 Discussion, contributions and limitations

This paper provides a novel, theoretically and empirically supported typology of free-to-play gamers and identifies different aspects of their purchasing behavior toward premium content. Our contribution to the literature is twofold. First, we complement existing gamer typologies by developing an empirically supported view of free-to-play gamers that is explicitly focused on value, to complement the literature that looks at other psychological factors, such as personality types [33], or motivations [70]. These findings result in the identification of one new gamer type (enthusiasts) that is relevant to the free-to-play VG industry and complement the mostly two-dimensional existing gamer typologies (e.g. [6]). Table 6 highlights the main characteristic(s) of each game type and compares it to types identified in extant literature. Second, we extend consumption values theory by identifying the multi-dimensional impact of value characteristics on purchase behavior in a context of emerging industrial and social importance. This reflects the further investigation requirements in the research agenda identified in Tanrikulu [68] that suggests there is merit in further understanding the perceived value in the purchase of new product types (e.g., premium content in our research) in the context of the digital world.

We utilized factor analysis to combine 16 items into more cohesive factors [72], which led to six objectively defined factors that were partially named using the constructs of consumption values theory. We specifically show that social and functional values were an important part of purchasing intention, as suggested by Mäntymäki & Salo [47, 48] and Ho & Wu [27]. Hedonic values identified by factor analysis in our research could be seen as a part of the emotional values described by Mäntymäki & Salo [47, 48], as they trigger an emotional response from the gamer. We then clustered these factors to develop a new and bespoke typology (RQ1), identifying five distinctive groups of users, who vary in their virtual goods purchasing and gaming behaviors (for RQ2 and its hypotheses H1 - H4). This allows us to identify distinct gamer groups and determine which types of gamers demonstrate specific values. We found that the only segment of players where paying users are in a minority (negativists, as shown in Table 3) vary from the other types mainly in their attitudes towards all of the consumer factors identified in the research, therefore aligning with Hsiao & Chen’s [28] research on differences between paying and non-paying players. Our categorization of types, therefore, builds on existing work such as Park and Lee [53], which show that certain value-generating constructs (e.g., character competency and enjoyment) and Hsiao & Chen [28] who find that user loyalty influences purchasing intentions.

In comparing our typology segment findings to the extant literature, we have identified two segments that have not so far been categorized, as the approach of this study is unique in its multidimensionality. First, we see that the economic aesthetes, although exhibiting some concepts from existing typologies, this exact type of gamer has not yet been identified. This is important, as we found that this segment constitutes around 20% of gamers and that 56.2% of gamers within this segment purchase premium content, with an average monthly spend usually up to 20 EUR. Second, negativists, who view all values with negative factor loadings, also purchase the lowest amount of premium content (just 29.9%). Negativists also tend to play least often of all segments, although almost 70% of gamers still admitted to playing at least twice a week. While it might appear that this type of gamer is not motivated to play the games, we only examined paying for premium content behavior, not general gaming behavior. Therefore, this type might be playing games casually, to kill time etc., and is possibly not as interested in gaming in the more general sense.

We also provide additional depth of detail about the other segments. Identification seekers are more likely to favor immersion in the game and can be likened to the explorers found in Bartle’s original typology [6], although relatively low values of the social factor nonetheless suggest differences. The largest segment (31.7%) in our analysis were the killers, who tend to be present in almost all gamer typologies [72] and are portrayed as gamers who prefer functional values as a way of being “better” than other players. In our research, we found that these players also do not prioritize hedonic values or value for money and killers tend to spend money on premium content, with a higher average monthly spend. Enthusiasts are an ideal target group for free-to-play game developers, as they have positive factor loadings across all values, particularly social and functional ones. Therefore, they take some elements from each of Bartle’s player types [6], reflecting the suggestion made by Tuunanen & Hamari [72] that traits rather than types should be used for future typologies. While Teng [69] posits that social values have a limited effect on the customer loyalty of general gamers, our research shows that the players who tend to spend the most money in-game, value social values highly. Enthusiasts are also the most likely to play daily (56.3%) and have a higher average monthly spend than any other type. Finally, our research addresses the question raised by Hamari & Keronen [23] on different purchasing behavior by different player types. We find that achievement-oriented players (killers) are more likely to purchase premium content in general. We suggest that, due to the preference for functional values of virtual goods, it is very likely that the killers purchase functional items, although statistical testing of this relationship is beyond our research, as we did not include questions about the specific nature of purchased goods.

The main practical implications of our findings are for free-to-play game developers, who wish to target specific groups with different types of in-game purchases. As per Aarseth [1], this could be achieved by combining a range of existing elements into a more appealing package. First, they can assess the players of their existing games to estimate the distribution of our proposed player types. This would seem to be mainly within the segment of enthusiasts, who seem to be key to the success of any free-to-play game, as they purchase premium content most often, have the highest intention of future purchases, and tend to spend most on average, making this segment the most profitable. Based on our research, this group of gamers most highly value social, functional and hedonic factors. Therefore, developers should cater to those values: for example, the social value construct comprises reviews, recommendations, as well as newsletters. The developer can provide some of these, whilst also motivating users to create reviews and recommend the game or premium content items to other players through various incentive systems. The hedonic values, which are also highly valued by economic aesthetes, suggest that developers should prioritize making the premium content as visually appealing as possible, while high values of the functional value mean the content needs to give the purchasing player a benefit over non-paying players.

The identification of specific gamer types that have a higher or lower likelihood of purchasing premium content can be used to guide game development and marketing activities tailored to specific groups, e.g. the negativists are less likely to purchase premium content. Also, this knowledge can contribute to the personalization of products, which is seen as an emerging trend and requirement in new product development, e.g., [35]), in which user experience is a key characteristic [78] and player-centered game design is important [58, 67]. By identifying more focused gamer types, our findings also complement the extant literature, by providing opportunities for more personalized correspondence, e.g., to achieve better responses to customer surveys [26] and personalized advertisements on social media [14].

5.1 Limitations and future research possibilities

The main limitation of our research is the sampling procedure and respondent recruitment. To gain a significant number of respondents, we posted our questionnaire on gaming communities (Facebook groups and specialized gaming forums) for various free-to-play games. This meant that hardcore gamers, who are part of these closely bonded communities would inevitably be targeted, rather than casual gamers. Our results on the quantity and amounts of premium content purchase per se, therefore, do not generalize to the overall gaming public, but this can be balanced by a lack of a sampling frame and casual gamers are often well-dispersed in the general population in terms of age, gender and socioeconomic characteristics. This problem is further highlighted by the fact that although free-to-play games form an important part of the overall gaming industry, they are nonetheless part of a larger games market with different revenue and cost models. Further qualitative research could develop the field’s understanding of the underlying reasons why gamers in the negativist category are less likely to purchase premium content and could then identify how gamers switch between categories, leading to different purchasing behavior. Future research could also include other intentions for playing free-to-play games, i.e., not only the behavior for purchasing within-game premium content and this might allow for a fuller exploration of the negativists and enthusiast gamer types in particular.

It should also be noted that we utilized descending directionality of responses in the Likert scale, which might be problematic and lead to so-called left-side option bias, where respondents tend to choose options on the left side [45]. We suggest further studies opt for bidirectional ordering.

In line with other studies using the consumption values framework, our research focuses on purchase intentions and future studies, possibly those using a longitudinal approach could establish the link between gamer types and actual purchases, although it is noted that the data for this may be more challenging to collect. Further, from a gamer perspective, some of the extant literature focuses on specific games or game types and although our study is not focused on these dimensions, it is of course the case that individuals play different games and may exhibit different behaviors (and therefore purchase intentions) depending on these dimensions. Further research would therefore be useful in comparing how gamers adopt different behaviors depending on what game type they are playing.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality arrangements in the questionnaire but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aarseth E (2003) Playing research: methodological approaches to game analysis. Artnodes. https://doi.org/10.7238/a.v0i7.763

Agarwal P (2017) Economics of microtransactions in video games. Intelligent Economist. https://www.intelligenteconomist.com/economics-of-microtransactions/. Accessed 28 Aug 2018

Aladwani AM (2014) Gravitating towards Facebook (GoToFB): what it is? and how can it be measured? Comput Hum Behav 33:270–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.005

Alha K, Koskinen E, Paavilainen J, Hamari J (2014) Free-to-play games: professionals’ perspectives. Proceedings of Nordic Digra 2014 Gotland, Sweden 1–14

Angell RJ, Megicks P, Memery J, Heffernan T, Howell KE (2012) Discovering the older shopper: a behavioural typology. J Retailing Consumer Serv 19(2):259–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.01.007

Bartle R (1996) Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: players who suit MUDs. J MUD Res 1:19

Berlo K, Liblik K (2016) The business of micro transactions. Master thesis, Jonköping University, Sweden

Clement J (2021) Global video game market value from 2020 to 2025. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/292056/video-game-market-value-worldwide/. Accessed 5 May 2022

Clement J (2022) Free-to-play (F2P) mobile games market revenue worldwide from 2018 to 2021. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1107021/f2p-mobile-games-revenue/. Accessed 5 May 2022

Clement J (2022) Gaming revenue worldwide 2022, by segment. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/292751/mobile-gaming-revenue-worldwide-device/. Accessed 5 May 2022

Clement J, Statista (2022) https://www.statista.com/statistics/935930/ftp-games-revenue/#:~:text=In%202020%2C%20Honor%20of%20Kings,revenues%20during%20the%20measured%20period. Accessed 6 May 2022

Coldewey D (2019) Free to play games rule the entertainment world with $88 billion in revenue. Techcrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2019/01/18/free-to-play-games-rule-the-entertainment-world-with-88-billion-in-revenue/. Accessed 22 Sept 2020

de Best R (2022) Most popular NFT games as of January 10, 2022, based on user count. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1266486/blockchain-games-user-number/. Accessed 4 May 2022

De Keyzer F, Dens N, De Pelsmacker P (2015) Is this for me? How consumers respond to personalized advertising on social network sites. J Interact Advertising 15(2):124–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2015.1082450

Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ (1999) Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol Methods 4(3):272–299. https://doi.org/10.1037//1082-989X.4.3

Field AP (2013) Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: and sex and drugs and rock ‘n’roll. Sage, Los Angeles

Frank L, Salo M, Toivakka A (2015) Why buy virtual helmets and weapons? Introducing a typology of gamers. BLED 2015 Proceedings, pp 503–519

Fransen M, Verlegh P, Kirmani A, Smit E (2015) A typology of consumer strategies for resisting advertising, and a review of mechanisms for countering them. Int J Advertising 34:6–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2014.995284

Fullerton T (2008) Working with dramatic elements. In: Game design workshop. A playcentric approach to creating innovative games. Morgan Kaufmann, Burlington

Ghuman D, Griffiths MD (2012) A cross-genre study of online gaming: player demographics, motivation for play, and social interactions among players. Int J Cyber Behav Psychol Learn 2(1):13–29. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCBPL.2012010102

Götzenbrucker G, Köhl M (2009) Ten years later. Eludamos 3(2):309–324. https://doi.org/10.7557/23.6012

Grguric M (2022) Subscription monetization: a big mobile gaming trend. Udonis. https://www.blog.udonis.co/mobile-marketing/mobile-games/subscription-monetization. Accessed 7 May 2022

Hamari J, Keronen L (2017) Why do people buy virtual goods: a meta-analysis. Comput Hum Behav 71:59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.042

Hande K, Aslihan NV, Suphan N (2010) Discovering behavioral segments in the mobile phone market. J Consumer Mark 27:401–413. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761011063303

Hanner N, Zarnekow R (2015) Purchasing behavior in free to play games: concepts and empirical validation. Proceedings of Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), pp 3326–3335. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2015.401

Heerwegh D, Vanhove T, Matthijs K, Loosveldt G (2005) The effect of personalization on response rates and data quality in web surveys. Int J Social Res Methodol: Theory Pract 8(2):85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557042000203107

Ho CH, Wu TY (2012) Factors affecting intent to purchase virtual goods in online games. Int J Electron Bus Manag 10(3):204–212

Hsiao KL, Chen CC (2016) What drives in-app purchase intention for mobile games? An examination of perceived values and loyalty. Electron Commer Res Appl 16:18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2016.01.001

Hutcheson G, Sofroniou N (1999) The multivariate social scientist: introductory statistics using generalized linear models. Sage, Los Angeles

Ip B, Jacobs G, Watkins A (2008) Gaming frequency and academic performance. Australasian J Educational Technol 24(4):355–373. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1197

Jansz J, Tanis M (2007) Appeal of playing online first person shooter games. Cyberpsychol Behav 10(1):133–136. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9981

Ji W, Sun Y, Wang N, Zhang X (2017) Why users purchase virtual products in MMORPG? An integrative perspective of social presence and user engagement. Internet Res 27(2):408–427. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-04-2016-0091

Jimenez N, San-Martin S, Camarero C, San Jose Cabezudo R (2019) What kind of video gamer are you? J Consumer Mark 36(1):218–227. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-06-2017-2249

Johnson E (2014) A long tail of whales: half of mobile games money comes from 0.15% of players. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2014/2/26/11623998/a-long-tail-of-whales-half-of-mobile-games-money-comes-from-0-15. Accessed 14 Aug 2018

Kajtaz M, Witherow B, Usma C, Brandt M, Subic (2015) An approach for personalised product development. Procedia Technol 20:191–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2015.07.031

Kallio KP, Mäyrä F, Kaipainen K (2011) At least nine ways to play: approaching gamer mentalities. Games and Culture 6(4):327–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412010391089

Kim HW, Gupta S, Koh J (2011) Investigating the intention to purchase digital items in social networking communities: a customer value perspective. Inf Manag 48:228–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2011.05.004

Kumar V (2014) Making ‘freemium’ work. Harvard Business Rev 5:27–29

Li H, Sun CT (2007) Cash trade within the magic circle: free-to-play game challenges and massively multiplayer online game player responses. Proceedings of DiGRA 2007: Situated Play, pp 335–343

Lilly B, Nelson T (2003) Fads: Segmenting the fad-buyer market. J Consumer Mark 20:252–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760310472272

Lipkin N (2012) Examining indie’s independence: the meaning of ‘indie’ games, the politics of production, and mainstream co-optation. Loading 7(11):8–24

Lopez CE, Tucker CS (2019) The effects of player type on performance: a gamification case study. Comput Hum Behav 91:333–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.005

Lu HP, Hsiao KL (2010) The influence of extro/introversion on the intention to pay for social networking sites. Inf Manag 47:150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2010.01.003

Macchiarella P (n.d.) Trends in digital gaming: free-to-play, social, and mobile games. Parks Associates. http://www.parksassociates.com/bento/shop/whitepapers/files/Parks%20Assoc%20Trends%20in%20Digital%20Gaming%20White%20Paper.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2022

Maeda H (2015) Response option configuration of online administered Likert scales. Int J Soc Res Methodol 18(1):15–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2014.885159

Malhotra NK, Birks DF (2006) Marketing research: an applied approach, 2nd Europe. FT Press, New Jersey

Mäntymäki M, Salo J (2011) Teenagers in social virtual worlds: continuous use and purchasing behavior in Habbo Hotel. Comput Hum Behav 27(6):2088–2097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.06.003

Mäntymäki M, Salo J (2015) Why do teens spend real money in virtual worlds? A consumption values and developmental psychology perspective on virtual consumption. Int J Inf Manag 35(1):124–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.10.004

Marczewski A (2015) User types. Even ninja monkeys like to play: gamification, game thinking and motivational design, 1st edn. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, pp 65–80

Mogre R, Lindgreen A, Hingley M (2017) Tracing the evolution of purchasing research: future trends and directions for purchasing practices. J Bus Industrial Mark 32(2):251–257. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-01-2016-0004

Nacke LE, Bateman C, Mandryk RL (2014) BrainHex: a neurobiological gamer typology survey. Entertainment Comput 5(1):55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2013.06.002

Newzoo (2018) Top countries & markets by game revenues. Newzoo. https://newzoo.com/insights/rankings/top-100-countries-by-game-revenues/. Accessed 30 Aug 2018

Park BW, Lee KC (2011) Exploring the value of purchasing online game items. Comput Hum Behav 27(6):2178–2185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.06.013

Parks L, Guay RP (2009) Personality, values, and motivation. Pers Indiv Differ 47(7):675–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.002

Paul J, Rana J (2012) Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food. J Consumer Mark 29(6):412–422. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761211259223

Qutee (2018) Gaming today report. https://www.qutee.com/q/gaming-today-report/. Accessed 28 Apr 2019

Richter F (2020) Gaming: the most lucrative entertainment industry by far. Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/22392/global-revenue-of-selected-entertainment-industry-sectors/. Accessed 5 May 2022

Ried MO (2011) Scalable personalization of interactive experiences through creative automation. Comput Entertain 8(4):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1145/1921141.1921146

Sandy CJ, Gosling SD, Durant J (2013) Predicting consumer behavior and media preferences: the comparative validity of personality traits and demographic variables. Psychol Mark 30(11):937–949. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20657

Schuurman D, De Moor K, Marez L, Looy J (2008) Fanboys, competers, escapists and time-killers: a typology based on gamers’ motivations for playing video games. Proceedings – 3rd International Conference on Digital Interactive Media in Entertainment and Arts, DIMEA 2008, pp 46–50. https://doi.org/10.1145/1413634.1413647

Sezan Sezgin (2020) Digital player typologies in gamification and game-based learning approaches: a meta-synthesis. Bartın Üniversitesi Egitim Fakültesi Dergisi 9(1):49–68. https://doi.org/10.14686/buefad.610524

Shang RA, Chen YC, Huang SC (2012) A private versus a public space: Anonymity and buying decorative symbolic goods for avatars in a virtual world. Comput Hum Behav 28(6):2227–2235

Sheth JN, Newman BI, Gross BL (1991) Why we buy what we buy: a theory of consumption values. J Bus Res 22(2):159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(91)90050-8

Stack Exchange (2016) What’s the difference between “free” versus “free to play” on steam? Stack Exchange. https://gaming.stackexchange.com/questions/247727/whats-the-difference-between-free-versus-free-to-play-on-steam#:~:text=%22Free%22%20means%20the%20game%20is,payment%20to%20get%20hold%20of. Accessed 16 May 2022

Statista (2021) Video Games. Statista. https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digital-media/video-games/worldwide. Accessed 5 May 2022

Sweeney JC, Soutar GN (2001) Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J Retail 77(2):203–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00041-0

Sykes J, Federoff M (2006) Player-centred game design. CHI ’06 extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems, pp 1731–1734

Tanrikulu C (2021) Theory of consumption values in consumer behaviour research: a review and future research agenda. Int J Consumer Stud 45(6):1176–1197. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12687

Teng CI (2018) Look to the future: enhancing online gamer loyalty from the perspective of the theory of consumption values. Decis Support Syst 114:49–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2018.08.007

Tseng FC (2011) Segmenting online gamers by motivation. Expert Syst Appl 38(6):7693–7697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2010.12.142

Turel O, Serenko A, Bontis N (2010) User acceptance of hedonic digital artifacts: a theory of consumption values perspective. Inform Manag 47(1):53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2009.10.002

Tuunanen J, Hamari J (2012) Meta-synthesis of player typologies. Proceedings of nordic digra 2012 conference: local and global - games in culture and society

Vahlo J, Kaakinen JK, Holm SK, KoponenA (2017) Digital game dynamics preferences and player types. J Computer-Mediated Communication 22(2):88–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12181

Wang GY, Yan J, Qin J (2021) From freemium to premium: the roles of consumption values and game affordance. Inform Technol People 34(1):297–317. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-10-2019-0527

Wijman T (2020) Three billion players by 2023: engagement and revenues continue to thrive across the global games market. Newzoo. https://newzoo.com/insights/articles/games-market-engagement-revenues-trends-2020-2023-gaming-report/. Accessed 5 May 2022

Wijman T (2021) Global Games Market to Generate $175.8 Billion in 2021; despite a slight decline, the market is on track to surpass $200 billion in 2023. Newzoo. https://newzoo.com/insights/articles/global-games-market-to-generate-175-8-billion-in-2021-despite-a-slight-decline-the-market-is-on-track-to-surpass-200-billion-in-2023/. Accessed 3 May 2022

Xu Y, Poole ES, Miller AD, Eiriksdottir E, Kestranek D, Catrambone R, Mynatt ED (2012) This is not a one-horse race: understanding player types in multiplayer pervasive health games for youth. In: Proceedings of the ACM 2012 conference on computer supported cooperative work. ACM, pp 843–852

Zheng P, Yu S, Wang Y, Zhong RY, Xu X (2017) User-experience based product development for mass personalization: a case study. Procedia CIRP 63:2–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2017.03.122

Funding

This contribution was created within the project SGS funded by the Faculty of Economics, VŠB-Technical University of Ostrava, project name Identification of Reference Groups Roles in Buying and Consumer Behaviour, project registration number SP2018/125.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest/Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Questionnaire statements

-

10.1. I am satisfied with this type of games.

-

10.2. When I play free-to-play games, I am more satisfied than I am playing paid games.

-

10.3. When I play an online game, I identify myself with the game character.

-

10.4. The goals of the character become my own goals.

-

10.5. The price of a virtual goods is reasonable.

-

10.6. Virtual goods is a good product given the price.

-

10.7. If I use a virtual goods, I can enjoy the game more.

-

10.8. I buy a virtual goods, because it gives me an advantage in the game.

-

10.9. I buy a virtual goods, because I want to improve my self-expression to other players.

-

10.10. I buy a virtual goods, because my game character(s) look better and/or more attractive.

-

10.11. When I buy a virtual goods, it is important to me that I support the game developer for their work as well as the future development of the game.

-

10.12. Using a virtual goods helps me make new friends.

-

10.13. I buy game bonuses that bring some advantages (e.g. faster healing, faster restoring mana, faster getting materials, more XP, etc.)

-

10.14. I buy virtual goods that bring new equipment to the game (heroes, tanks, additional equipment for heroes, etc.)

-

10.15. I buy virtual goods that change the game design (skins for equipment, avatars, changing of profile picture, changing view of game surroundings, etc.)

-

10.16. If possible, I buy a premium account which brings me more advantage together.

-

10.17. Special events motivate me to buy virtual goods (Halloween events, Christmas events, Easter events, Birthday of game events, Summer events, etc.)

-

10.18. Newsletters or banners with news in the game motivate me to buy virtual goods.

-

10.19. Recommendations from friends motivate me to buy virtual goods in the game.

-

10.20. Review from streamers motivate me to buy virtual goods in the game.

-

10.21. Virtual goods has an acceptable standard of quality.

-

10.22. Virtual goods is graphically sophisticated enough.

-

10.23. The offer of virtual goods is sufficient.

-

10.24. The offer volume of virtual goods should be extended.

-

10.25. Virtual goods creates improper balance in the game.

-

10.26. My willingness to buy virtual goods will grow in the future.

-

10.27. I would buy more virtual goods if I played the game long enough.

Appendix 2: Tukey’s HSD test results

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klézl, V., Kelly, S. Negativists, enthusiasts and others: a typology of players in free-to-play games. Multimed Tools Appl 82, 7939–7960 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-13647-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-022-13647-9