Abstract

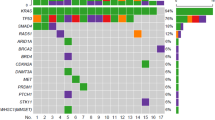

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the deadliest cancers in humans, with less than 5% 5-year survival rate. PDAC is characterized by a small number of recurrent mutations, including KRAS, CDKN2A, TP53, and SMAD4 and a long “tail” of infrequent mutated genes. Most of the studies have been performed in US and European populations, so new studies are needed to describe the mutational landscape of these tumors in other cohorts. The present study analyzed the exome and transcriptome of four PDAC tumors from Mexican patients. We found a paucity of the previously described recurrent mutations, with mutations in only three genes (HERC2, CNTNAP2 and HMCN1) previously reported in PDAC with a frequency > 1%. In addition, we discovered several recurrent putative copy number aberrations in SKP2, BRAF, CSSF1R, FOXE1, JAK2 and MET genes and in genes previously reported as putative drivers in PDAC, including KRAS, SF3B1, BRAF, MYC and MET. Although a larger cohort is needed to validate these findings, our results could be pointing toward potential differences in contributing factors for PDAC in Latin-American populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Li J et al (2010) Identification of high-quality cancer prognostic markers and metastasis network modules. Nat Commun 1:34. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1033

Gonzalez-Santiago O, Yeverino-Gutierrez ML, Del Rosario Gonzalez-Gonzalez M, Corral-Symes R, Morales-San-Claudio PC (2017) Mortality assessment of patients with pancreatic cancer in Mexico, 2000–2014. Ecancermedicalscience 11:788. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2017.788

Setiawan VW et al (2019) Pancreatic cancer following incident diabetes in African Americans and Latinos: the multiethnic cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst 111:27–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy090

Palloni A, Beltran-Sanchez H, Novak B, Pinto G, Wong R (2015) Adult obesity, disease and longevity in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 57(Suppl 1):S22–S30. https://doi.org/10.21149/spm.v57s1.7586

Nothlings U et al (2007) Body mass index and physical activity as risk factors for pancreatic cancer: the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Cancer Causes Control 18:165–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-006-0100-0

Zavala-Arciniega L et al (2020) Smoking trends in Mexico, 2002–2016: before and after the ratification of the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Tob Control. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055153

Pushalkar S et al (2018) The pancreatic cancer microbiome promotes oncogenesis by induction of innate and adaptive immune suppression. Cancer Discov 8:403–416. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1134

Aykut B et al (2019) The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL. Nature 574:264–267. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1608-2

Wei MY et al (2019) The microbiota and microbiome in pancreatic cancer: more influential than expected. Mol Cancer 18:97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-019-1008-0

Neoptolemos JP et al (2017) Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389:1011–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32409-6

Yu X, Zhang Y, Chen C, Yao Q, Li M (2010) Targeted drug delivery in pancreatic cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1805:97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.10.001

Bardeesy N, DePinho RA (2002) Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nat Rev Cancer 2:897–909. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc949

Connor AA et al (2017) Association of distinct mutational signatures with correlates of increased immune activity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncol 3:774–783. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3916

Bailey P et al (2016) Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature 531:47–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16965

Kwon MJ et al (2015) Low frequency of KRAS mutation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas in Korean patients and its prognostic value. Pancreas 44:484–492. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0000000000000280

Bournet B, Buscail C, Muscari F, Cordelier P, Buscail L (2016) Targeting KRAS for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of pancreatic cancer: hopes and realities. Eur J Cancer 54:75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.11.012

Witkiewicz AK et al (2015) Whole-exome sequencing of pancreatic cancer defines genetic diversity and therapeutic targets. Nat Commun 6:6744. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7744

Li H, Durbin R (2010) Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26:589–595. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698

McKenna A et al (2010) The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 20:1297–1303. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.107524.110

DePristo MA et al (2011) A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 43:491–498. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.806

Van der Auwera GA et al (2013) From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinform 43:11–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43

Cibulskis K et al (2013) Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol 31:213–219. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2514

Ramos AH et al (2015) Oncotator: cancer variant annotation tool. Hum Mutat 36:E2423–E2429. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.22771

Boeva V et al (2012) Control-FREEC: a tool for assessing copy number and allelic content using next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28:423–425. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr670

Vogelstein B et al (2013) Cancer genome landscapes. Science 339:1546–1558. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1235122

Forbes SA et al (2015) COSMIC: exploring the world’s knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D805–D811. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1075

Thorvaldsdottir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP (2013) Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform 14:178–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbs017

Whitehall V et al (2009) A multicenter blinded study to evaluate KRAS mutation testing methodologies in the clinical setting. J Mol Diagn 11:543–552. https://doi.org/10.2353/jmoldx.2009.090057

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155:945–959

Zuniga J et al (2013) HLA class I and class II conserved extended haplotypes and their fragments or blocks in Mexicans: implications for the study of genetic diversity in admixed populations. PLoS ONE 8:e74442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074442

Waddell N et al (2015) Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 518:495–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14169

Alexandrov LB et al (2013) Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500:415–421. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12477

Choi Y, Chan AP (2015) PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics 31:2745–2747. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv195

Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC (2009) Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc 4:1073–1081. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2009.86

McWilliams RR et al (2018) CDKN2A germline rare coding variants and risk of pancreatic cancer in minority populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 27:1364–1370. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1065

Marker KM et al (2020) Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer is associated with indigenous American ancestry in Latin American women. Cancer Res 80:1893–1901. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3659

Li M et al (2017) Whole-genome sequencing reveals the mutational landscape of metastatic small-cell gallbladder neuroendocrine carcinoma (GB-SCNEC). Cancer Lett 391:20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2016.12.027

Lee SH, Je EM, Yoo NJ, Lee SH (2015) HMCN1, a cell polarity-related gene, is somatically mutated in gastric and colorectal cancers. Pathol Oncol Res 21:847–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-014-9809-3

Yue T, Tian A, Jiang J (2012) The cell adhesion molecule echinoid functions as a tumor suppressor and upstream regulator of the Hippo signaling pathway. Dev Cell 22:255–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.011

Gruber R et al (2016) YAP1 and TAZ control pancreatic cancer initiation in mice by direct up-regulation of JAK-STAT3 signaling. Gastroenterology 151:526–539. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.05.006

Arrieta O et al (2015) Different mutation profiles and clinical characteristics among Hispanic patients with non-small cell lung cancer could explain the “Hispanic paradox”. Lung Cancer 90:161–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.08.010

Aguirre AJ et al (2003) Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev 17:3112–3126. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1158703

Krasinskas AM, Moser AJ, Saka B, Adsay NV, Chiosea SI (2013) KRAS mutant allele-specific imbalance is associated with worse prognosis in pancreatic cancer and progression to undifferentiated carcinoma of the pancreas. Mod Pathol 26:1346–1354. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.71

Chen Y et al (2014) Identification of druggable cancer driver genes amplified across TCGA datasets. PLoS ONE 9:e98293. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098293

Liu ML et al (1998) Amplification of Ki-ras and elevation of MAP kinase activity during mammary tumor progression in C3(1)/SV40 Tag transgenic mice. Oncogene 17:2403–2411. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1202456

Sierra JR, Tsao MS (2011) c-MET as a potential therapeutic target and biomarker in cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol 3:S21–S35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758834011422557

Garajova I, Giovannetti E, Biasco G, Peters GJ (2015) c-Met as a target for personalized therapy. Transl Oncogenomics 7:13–31. https://doi.org/10.4137/TOG.S30534

Li CF et al (2012) Characterization of gene amplification-driven SKP2 overexpression in myxofibrosarcoma: potential implications in tumor progression and therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res 18:1598–1610. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3077

Einama T et al (2006) High-level Skp2 expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: correlation with the extent of lymph node metastasis, higher histological grade, and poorer patient outcome. Pancreas 32:376–381. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mpa.0000220862.78248.c4

Funding

Paulina Sanchez is a Doctoral Student from Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias Biomédicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and received a Fellowship 397501 from CONACyT. Rodrigo Barquera is a Doctoral Student funded by the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany. This work was supported by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (CONACyT) Grant Number 2011-CO1-161619.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PS performed experiments and data analysis. ME performed experiments. RB performed the ancestry analyses. VM integrated results and drafted the manuscript. NBG performed pathologic assessments. JT and AC performed clinical analyses, helped collect the samples and obtained the clinical information. JM-Z performed data analysis, designed the study, integrated the results and drafted the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Ethical approval

The project was approved by Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genomica’s (INMEGEN) Ethical, Biosecurity and Scientific Committees, by the Scientific Committee of Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) and by Mexico’s Federal Health Regulation Office COFEPRIS (Comision Federal para la Proteccion contra Riesgos Sanitarios, project Genomica del Cancer. Capitulo Mexico CMN2011-020). All procedures were performed according to the guidelines and regulations approved by these Committees.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanchez, P., Espinosa, M., Maldonado, V. et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas from Mexican patients present a distinct genomic mutational pattern. Mol Biol Rep 47, 5175–5184 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-020-05592-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-020-05592-3