Abstract

Arabinogalactan Proteins (AGPs) are hydroxyproline-rich proteins containing a high proportion of carbohydrates, widely spread in the plant kingdom. AGPs have been suggested to play important roles in plant development processes, especially in sexual plant reproduction. Nevertheless, the functions of a large number of these molecules, remains to be discovered. In this review, we discuss two revolutionary genetic techniques that are able to decode the roles of these glycoproteins in an easy and efficient way. The RNA interference is a frequently technique used in plant biology that promotes genes silencing. The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)—associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9), emerged a few years ago as a revolutionary genome-editing technique that has allowed null mutants to be obtained in a wide variety of organisms, including plants. The two techniques have some differences between them and depending on the research objective, these may work as advantage or disadvantage. In the present work, we propose the use of the two techniques to obtain AGP mutants easily and quickly, helping to unravel the role of AGPs, surely a great asset for the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) belong to the supefamily of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins (HRGPs), and most of them are predicted to be tethered to the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor [1,2,3].

These characteristics always made them predictable candidates to be involved in signalling mechanisms, in several plant developmental processes [4]. Showalter et al. [5] identified 85 AGPs in Arabidopsis, divided into five classes: classical AGPs, lysine-rich AGPs, AG peptides, fasciclin-like AGPs (FLAs), and other chimeric AGPs [6, 7]. These glycoproteins, ubiquitous in the plant kingdom, have crucial roles in multiple biological processes, including cell division, cellular communication, programmed cell death, embryogenesis, secondary wall deposition, organ abscission, plant–microbe interactions, and reproductive processes [4, 8,9,10,11,12,13].

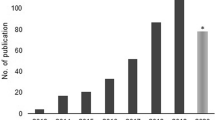

AGPs have been subject to innumerous studies in the recent years, which have tried to tackle its functions in plants. Even though, their specific mode of action and the functions of many specific AGPs remains largely unknown.

Due to the complexity of their AG sugar chains and the heterogeneity of their core proteins these molecules are difficult to study. Besides, in large families, redundancy is a problem when one intends to obtain a phenotype and understand the function of a protein [14]. Therefore, the AGPs functional redundancy due to the similarity between its aminoacidic sequences, further interferes with the study of their functions [15,16,17,18]. Despite this, the work being developed with tools such as the anti-AG chain-based immunomicroscopy, β-Yariv reagents, enzymes that target specific parts of AG chains, chemical synthesis of specific structures of AG chains and bioinformatics, is slowly clarifying the nature of AGPs [19]. Moreover, with the development of powerful molecular biology tools, it is possible a genetic approach that offers a great alternative to identify a specific AGP function [20]. The use of several approaches to control gene expression, since the first classical genetic studies until the most recent molecular techniques, has revealed to be essential to determine the functions of different genes correlating them with phenotypes and integrating them in several biological pathways.[21]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, reverse genetic techniques to isolate mutants corresponding to known sequences, such as antisense suppression, co-suppression by overexpression of the target gene, targeted gene disruption, or the PCR approach of screening for T-DNA insertion libraries, have been developed, but are often insufficient and have many unexpected difficulties [22]. These limitations can be partially overcome by new genetic approaches. One classical strategy that has been established for plant functional genetics research, including functional studies for AGPs, is the loss-of-function by RNA interference (RNAi), a great transient gene-expression repression approach discovered over a decade ago [23]. Recently, a new genome engineering technique, using type II clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) from Streptococcus pyogenes, is becoming a powerful tool for functional genomics research in plants [24]. In this review, we describe the best CRISPR/Cas9 and RNAi approaches to obtain AGP mutants, with the intention of getting to know more about the biological function of AGPs.

RNA interference (RNAi)

Possibly, one of the most important advances from the past decades has been the discovery that RNA molecules can regulate the expression of genes [25]. In 1998, the group of Fire and Mello [23] announced their discovery of RNAi—the silencing of gene expression by double stranded RNA molecules—in nematode worms. From this discovery emerged the notion that a number of previously characterized, homology-dependent gene-silencing mechanisms might share a common biological origin. Between the 80's and 90's, plant biologists working with petunias were surprised to find that introducing numerous copies of a gene encoding deep purple flowers led to white or patchy flowers plants, instead of an expected even darker purple color [26, 27]. Somehow, the introduced transgenes had silenced both their own ‘purple-flower’ genes. In parallel, several research groups found that plants responded to viruses RNA by targeting viral RNAs for destruction [28,29,30,31]. Most of the techniques used to induce gene silencing have been shown to share many mechanistic similarities, such as RNAi, co-suppression and virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS). Even the biological pathways which are the core of dsRNA-induced gene silencing are present in most eukaryotic organisms [32].

RNAi is based in the natural pathways of RNA silencing. The first pathway, siRNA silencing, may be important in virus-infected plant cells, where the dsRNA could be a replication intermediate or a secondary-structure feature of single-stranded viral RNA. In plant DNA viruses, the dsRNA may be formed by annealing of overlapping transcripts. The second pathway is the silencing of endogenous messenger RNAs by miRNAs, these are originated from single-stranded transcripts. The miRNAs bind to specific mRNAs by base pairing, and in this way, negatively regulate a specific gene expression, either by RNA cleavage or by disturbing its translation process [33]. Thus, these two classes of silencing RNAs (sRNAs), short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs), affect gene expression in animals and plants, presenting differences between them. The siRNAs are a class of double-stranded RNAs of 21–22 nucleotides in length, generated from dsRNAs. siRNAs silence genes by promoting the cleavage of mRNAs with exactly complement sequences. miRNAs are a class of 19–25-nucleotide, single-stranded RNAs that are encoded in the genomes of multicellular organisms, these are evolutionarily conserved and developmentally regulated. They silence genes interfering with protein translation [25, 34]. sRNAs interfere with normal gene function on several levels, including promoter activity, mRNA stability, and translational efficiency. These small RNAs derive from double-stranded RNA precursor molecules that are cleaved by a specialized class of RNases, the Dicer family which has RNase III domains, into short 21–26 nucleotide small RNAs [33,34,35]. In animals, dicers are named DCRs, and in plants Dicer-like (DCL) proteins.

Chuang and Meyerowitz [22] have shown that it is possible to induce sequence-specific inhibition of gene function in an efficient way by dsRNA-mediated genetic interference in Arabidopsis thaliana. siRNAs and miRNAs are produced in the genome of A. thaliana, by the cleavage of dsRNAs by the Dicer-like gene family, which has only four members: Dicer-like (DCL) 1, 2, 3 and 4. Plant sRNAs precursors are processed in the nucleus by DCL1, releasing the cleaved sRNA duplexes, but usually one of the two constituent sRNAs are preferably associated with ARGONAUTE (AGO), in Arabidopsis AGO1. This strand has been termed the siRNA guide strand, and in the case of miRNAs, corresponds to the mature miRNA. Plant miRNAs pair almost perfectly to their target RNA using preferentially transcript cleavage and subsequent degradation, instead of translation suppression as the silencing mechanism [36].

Silencing RNAs serve as specific components for protein machines known as RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISCs), which contain as catalytic subunits, ARGONAUTE proteins, the mediators of gene silencing, since they cleave target mRNAs, followed often by degradation of the cleaved RNA [33, 37, 38] (Fig. 1).

Schematic representation of the RNAi mechanism. The double-strand RNA (dsRNA) may occur in the cell as exogenous RNAs introduced by viruses or created in laboratory, or as endogenous RNAs transcribed from nuclear genes. These dsRNAs are recognized and processed into small interfering RNAs by Dicer in siRNA or miRNA, respectively. These sRNAs associate with RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISC), which contain a catalytic protein, ARGONAUTE (AGO). If, the pairing with mRNA target sequence and siRNA is 100%, the AGO cleaves target mRNA and promotes its degradation. In the other hand, if the pairing is not perfect (< 100%) this cleavage does not occur and the mRNA/RISC complexes are associated with P bodies with consequent inhibition of translation. The two pathways culminate in the reduction of gene expression

One of the most developed and effective ways to generate siRNAs in plants is by using long hairpin precursors; this approach is known as inverted repeat, post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) or hairpin RNAi (hpRNAi) [39]. In this case, sense and antisense RNAs are so close that dsRNA is easily formed. The use of hpRNAi is extensively used for many plant species, since many generic plasmids for transgene generation have been made available by the scientific community [34]. On the other hand, plants miRNAs have musch less off targets than animal miRNAs [35, 40], which is a positive feature for most of the silencing studies aiming to silence a specific gene rather than a set of genes. When the artificial miRNAs (amiRNAs) are produced and inserted into the cells, the endogenous miRNAs precursors form sRNAs that consequently lead to gene silencing [35, 41,42,43,44]. miRNA precursors preferentially produce one sRNA duplex, the miRNA–miRNA* duplex. When both sequences are modified without changing structural features, this often leads to high-level accumulation of a miRNA of a desired sequence. amiRNAs are effective when expressed from either constitutive, such as the 35S promotor, or tissue-specific promoters and plant amiRNAs have similarly high specificity as endogenous miRNAs. amiRNAs were used in Arabidopsis [43], where they were shown to effectively interfere with reporter gene expression. The online platform MicroRNA Designer (WMD3) [34, 35] uses sequences of target genes as an input to design artificial microRNAs (amiRNAs), which can be genetically engineered and function to specifically silence genes of interest. After the platform performs a search for candidate 21-mers sequences that are similar to natural miRNAs in the whole length of reverse complements of target transcripts, it is just necessary to select the favorite candidates [34, 35]. Some of the advantages of using amiRNA directed gene silencing are greater specificity and less off-target effects compared to traditional inverted-repeats gene silencing vectors [45]. After choosing the best amiRNA, the WMD includes the ‘Oligo’ tool [34], which allows automatic generation of oligonucleotide primers that can be used in combination with the MIR319a precursor from A. thaliana. Both miRNA and the partially complementary region, the miRNA*, are replaced by amiRNA and amiRNA*, respectively. As structural features are considered important for guiding correct DCL1-mediated processing, the amiRNA sequence is specified so away that mismatch positions to the amiRNA* are retained [34]. Lastly, the chimeric sequence is then transferred to a vector of choice prepared to receive the created construction and transferred to A. thaliana by the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

The AGPs are a large family and several T-DNA mutants exist, but not enough to study each AGP specific function. RNAi techniques have been used to elucidate gene function by creating knockdown mutants for these glycoproteins. To define the AGP18 function, Acosta Garcia and Vielle Calzada [46], used RNAi-induced posttrancriptional silencing, specifically degrading the endogenous AGP18 transcripts. The RNAi technique allowed them to demonstrate that this classical AGP is essential for female gametogenesis in A. thaliana. Another work on specific AGP functions is the study of agp6agp11 and their role in pollen grain development [14]. This work has been accomplished using gene silencing studies that created two Arabidopsis transgenic lines by RNAi technology, silencing both AGP6 and AGP11. The comparison of RNAi mutants (knockdown) and knockout mutants created by T-DNA insertion was essential to confirm these AGP phenotypes. Down-regulation of AGP6 and AGP11 by RNAi and artificial microRNA led to pollen grain abortion, inhibition of pollen tube growth, and reduction of fertility [14, 47].

FLA3 is a fasciclin-like Arabinogalactan protein predicted to be involved in microspore development of Arabidopsis. The involvement of this protein in microspore development and pollen intine formation was revealed by RNAi plants, a useful tool to discover AGP functions [48]. More recently, the function of AGP4/JAGGER was identified by studying not only knock out mutants for this glycoprotein, but also one RNAi line [49]. This line (jagger_RNAi) allowed the reduction of JAGGER expression only in certain tissues of the flower, allowing the author to determine the exact pistil tissue responsible for its function. Therefore, in this case the RNAi line was crucial to determine the AGP4 function.

A specific group of chimeric AGPs, belonging to the early nodulin-like proteins (ENODLs), related to the phytocyanin family, are very similar to classical AGPs: EN11-EN15 and were shown to play important roles in plant reproduction [13]. Hou et al. [50] when studying the function of polarly localized ENs, could not obtain null mutations by T-DNA insertion for all the five ENODLs. So they created higher order mutants by introducing an RNAi silencing construct for EN11/EN12 into the triple mutant en13en14en15 and an en-RNAi mutant that contained the loss of function of EN13 EN14 EN15 and lowered expression of EN11 and EN12, respectively. In this case, RNAi technology was crucial to understand that these proteins played an essential role in male–female communication and fertilization, especially in pollen tube reception.

At this moment, it is clear that RNAi technology is vital to discover AGPs specific functions, and the discovery of RNA silencing completely changed the perspective of reverse genetic studies. RNAi is an efficient alternative method to study and determine the function of an individual AGP, and it is reasonable to consider that in the future, RNAi will keep a certain unique space in these studies.

CRISPR/Cas9

With a higher interest in genome editing in the recent years, a new technology has emerged to fulfil the dream of modifying, precisely and efficiently, the genomic DNA of cellular organisms. This technology, based upon the two component CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9) system, is an adjustable bacterial immune system, which helps the bacteria protecting itself against invading foreign DNA, such as the one from a bacteriophage. This process uses RNA-guided nucleases to cleave foreign genetic elements, and in recent years, it has become a resourceful molecular tool for genome editing in various organisms, including plants [51,52,53,54]. These CRISPR/Cas systems can be classified into types II and III, being the type II CRISPR/Cas system adapted as a genome-engineering tool [55]. CRISPR system comprises a group of genes associated with CRISPR, Cas, non-coding RNAs and a distinct matrix of repetitive elements (direct repeats). These repeats are interspersed by short variable sequences derived from DNA exogenous targets, with homology to them, known as protospacers, and together they constitute the CRISPR RNA (crRNA). Within the DNA target, each spacer is always associated with a small conserved sequence named Protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). These small sequences are targets of the Cas endonucleases, thus allowing the system to distinguish its own DNA from foreign DNA. If the bacteria are invaded, a second time by the same invader, the crRNA encoding the 20nt guide RNA and an auxiliary trans-activation crRNA (tracrRNA) generates a complex with Cas9 (crRNA:tracrRNA:Cas9). This tracrRNA usually helps the process as it facilitates the division of the crRNAs in discrete units. The complex formed looks for the DNA sequence with a PAM motif, complementary to the crRNA and binds to it by Watson–Crick base pairing. Finally, Cas9 separates the DNA target from the double strand and cleaves the two strands in a location close to the PAM motif, thus destroying the invader [56,57,58,59]. In order to use this system in genetic engineering, the crRNA and tracrRNA were fused to create a chimeric single-stranded RNA (sgRNA) that present a designed hairpin to mimic the crRNA–tracrRNA complex [51]. This discovery created a simple two-component system (sgRNA and Cas9), being possible to change the genomic target of Cas9 protein, simply by changing the target sequence present in sgRNA [60].

The Cas9 originates from different bacteria, being the Streptococcus pyogenes more used for its isolation. In this system, a Polymerase II promoter [61] expresses this endonuclease. In contrast, Polymerase III promoters, such as U6 and U3 from Arabidopsis [62], typically express sgRNAs. The sgRNA in 5′end has a 20 nucleotide sequence (protospacer) which acts as a guide to identify a target accompanied by the PAM motif (5′-NGG sequence). At its 3′end it presents a scaffold sequence necessary for the binding of Cas9 (Cas9:sgRNA complex), which cleaves the double-stranded DNA and forms a double-stranded breakdown (DSB) at 3 bp upstream of the PAM motif. These DSBs are repaired by evolutionarily conserved DNA repair pathways such as the non-homologous end joining method (NHEJ) or the homology direct repair (HDR). NHEJ is a repair system that connects the DSB by random insertion or deletion of short stretches of oligonucleotide bases. This can lead to a disruption of the codon-reading frame, resulting in wrong transcripts and ablation of gene expression. In HDR, there is the insertion of a DNA segment in regions homologues to the sequences flanking the two sides of the DSB, which makes the cells delivery system to embody an extra segment [63,64,65]. Therefore, NHEJ can lead to ablation of gene mutations and it can be used to knockout specific genes, and HDR can be used to introduce specific point mutations or introduce DNA segments of varying lengths into a specific gene [65]. The NHEJ method is the most used for genome editing because it is more efficient than HDR [66]. To give a more complete view of this technology, Fig. 2 presents a schematic representation of the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

Schematic representation of the CRISPR/Cas9 technique mechanism of action. The sgRNA (single guide RNA - orange) is formed by a sequence of 20nt that defines the genomic target that will be modified and a scaffold sequence (red). The scaffold sequence allows the formation of a complex with the Cas9 protein; the complex can detect target sequences in DNA that are complementary to the target sequence to be modified. If the target sequence is located directly upstream of a PAM (Protospacer adjacent motif- black) sequence, it is recognized by Cas9 leading to a double strand break (DSB) approximately 3 bp upstream of the PAM sequence. This break is usually repaired by NHEJ (non-homologous end joining) in most situations creating insertions/deletions in the gene leading to the complete loss by knockout. However, the break can be repaired by HDR (homology directed repair) creating a precise gene editing introducing specific point mutations. (Color figure online)

In order to obtain knockout mutants by the CRISPR technology it is necessary to plan the experiment, which normally consists of four principal stages: (i) sgRNA design for the target sequence. For this stage, it is necessary to design the 20nt guiding sequence, specific only for the target sequence, preceded by the PAM motif. There are, nowadays, diverse bioinformatics tools to design sgRNAs, which are able to inform us about the main characteristics needed to consider choosing the best one, depending on the specific target [67]. The selection of a sgRNA has to consider the 5′-NGG PAM for S.pyrogenes Cas9 (a necessary sequence for Cas9 to bind the target DNA) and the minimization of off-target activity. Besides that, to generate genetic knockouts, sgRNAs commonly target 5′ constitutively expressed exons to reduce the chances that the targeted region is removed from the mRNA due to alternative splicing [68, 69]. Also, if the U6 (most common) RNA polymerase III promoter is used to express the sgRNA, the first base of its transcript should be a guanine (G) nucleotide. So, an extra G is added at the 5′ sgRNA, in a way that the 20nt guiding sequence does not start with G [70]. Occasionally, some sgRNAs may not work, thus there is the need of having at least two sgRNAs for each locus and the need to test their efficiencies in the intended cell type [58]. The second stage (ii) is to choose the best vector. In recent years, several researchers have developed vectors encoding the components of genome editing systems for CRISPR in plants. The choice of the vectors largely depends on the type of the expression system to work with, the restriction sites present to insert sgRNA, the sgRNA promotor (RNA polymerase III promotor) and the type of Cas9 system [71]. Several researchers have constructed different binary vectors that combine Cas9 endonuclease with the sgRNA, having the target gene sequence to induce modifications in several plant genes via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation method [72,73,74,75,76]. Xing and colleagues [77] generated a toolkit to set one or more sgRNA expression cassettes into a CRISPR/Cas9-based binary vector, using a Golden Gate Cloning system to amplify sgRNAs [78], this useful toolkit targets the mutation of multiple plant genes. In 2015, other CRISPR/Cas9 vector was reported to allow efficient assembly of multiple sgRNA expression cassettes into a single binary CRISPR/Cas9 vector, only in one cloning round [79], by the Golden Gate Assembly [80] or Gibson Assembly [81]. In the same year, Lowder and colleagues [61] developed a tool that does not require a PCR and can be used for transcriptional regulation with Cas9 fusion in plants. At the same time, Wang and colleagues [82] generated a vector for multiple sgRNAs cassettes with an egg cell-specific (EC1) promoter, to express Cas9 and obtain non-mosaic T1 CRISPR/Cas9 plants, since the mosaicism for the target gene was a problem. To solve this problem and improve the Floral Dip efficiency, a recent study created a extremely efficient CRISPR/Cas9 vector, pKAMA-ITACHI Red, using a RPS5A promoter to drive Cas9 [83]. The RP5A and EC1 promotors for Cas9 endonuclease are constitutively expressed in the egg cells or early embryo stage. If the expression of Cas9 and its subsequent induction of mutations occur in the initial cells or embryos as these promoters allow, the mutations are transferred to the next generation cells, and then all or most of the plant cells, including the meristematic region, will induce this mutation [83]. The pKAMA-ITACHI Red has one more advantage to isolate Cas9-free plants, because it contains an OLE1–TagRFP (red fluorescent protein) that exhibits red fluorescence in seeds, creating an easier and faster selection method, when compared to a PCR reaction. Cas9 deletion is essential to avoid off-targeted mutations and undesirable mutations of a wild-type allele [83]. The third stage (iii) includes the cloning of the sgRNAs in the vector. As already mentioned above, some binary vectors were generated to allow efficient assembly of multiple sgRNA expression cassettes with the Golden Gate or Gibson Assembly [78, 80, 81]. This method reports to its origins in 1996, when it was shown that multiple inserts could be assembled into a vector backbone using the type IIS restriction enzyme sequential or simultaneous activities together with T4 or T7 DNA ligase activities [84, 85]. Golden Gate or Gibson assembly is a flexible, efficient and easy method to clone multiple fragments into a vector, ideal for CRISPR/Cas9 technology, and just needs a recognition site for type IIS restriction enzyme in the final vector and in multiple fragments (sgRNAs), and a T4 or T7 ligase to assemble the fragments. This method works only in one tube and one-step [80]. The last stage (iv) consists in the delivery and expression of the vector into the plant. The most common method to transform plants with the CRISPR/Cas9 final vector is Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, which introduces the T-DNA directly into the plant genome [86]. Cas9 and sgRNA expression cassettes can be easily cloned into Ti plasmid, transformed into Agrobacterium and further introduced into the plants, with the Arabidopsis Floral Dip method, where the egg cell is the target of the T-DNA [87,88,89]. Besides that, the most recent generated vectors of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in plants have shown very positive results with the Floral Dip method [82, 83]. Therefore, this is an easy, efficient and fast method to obtain the transformed seeds that will give rise to the plants (T1 plants) with the desired edited genome.

Actually, the CRISPR/Cas9 technology is being used to obtain knockout mutants for several plant genes. Its efficiency improvement to isolate knockouts of interest was achieved, being important to study plants genetic redundancy, such as the case of AGPs [83]. However, there are still no mutants created by this technology to study the role of the AGPs large family, but the increasing interest in these proteins, together with the few available T-DNA lines and RNAi lines with visible phenotypes, it will not be long before the first CRISPR mutants are created to understand the functions of these glycoproteins.

CRISPR/Cas9 vs RNAi (advantages and disadvantages)

The most correct and usual approach to define gene function is to reduce or interrupt its normal expression. During the last decades, the RNAi technique, together with insertional mutants, has been intensively implemented to discover the function of many genes. However, the emergence of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology came to face these approaches. Nevertheless, while not able to completely disrupt gene function, the use of knockdowns can offer numerous advantages over knockouts. When intended to reduce gene expression only temporarily and if modification of the genetic code is undesirable, the best approach is RNAi-mediated knockdown, because sRNAs in some generations may be lost. It is also advantageous if complete elimination of gene function is detrimental to the cell but a partial loss is not [21, 90]. When one intends to eliminate all variants of transcripts or families of whole genes, this is possible using a single sgRNA against exons that are conserved among all members of the family [91]. This is a very important point in studies of large gene families. The CRISPR/Cas9 technique allows genome editing which leads to precise and predictable modifications [90].

When AGPs are being studied, these two powerful technologies present some advantages and some disadvantages, as summarized in Fig. 3. The main differences are the off-target activity, the length of the effect and the multiple genome editing. In these three cases, CRISPR/Cas9 is more useful because the off-targets can be eliminated, by designing the best sgRNA and choosing the low off-target score [92] and high on-target score [93]. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9 assures transmission of the heritable stable mutation [81, 82]. On the other hand, the RNAi technique may or may not generate offspring with reduced expression levels of the gene under study, because although the construct is transmitted to the next generation, the way that the RNAi mechanism acts is always different and sometimes the sRNA can be lost in the next generations [90]. The RNAi system turns out to be less reliable, and always necessary to check the expression levels of the gene of interest in all generations and in all plants, making it a more laborious and expensive method. However, it depends on the research goal, to choose a transient or permanent mutation [21].

To explore the role of gene family members with redundant functions, mutations in multiple genes in normally necessary. Therefore, the multiple genome editing is important, because it creates a mutation in multiple similar genes at the same time [81].

This review intends to show that both of these techniques are important and essential to understand the function of AGPs depending on the objective. RNAi has already proven its importance in discovering the roles of various AGPs, as mentioned in the previous section, and certainly, CRISPR/Cas9 will similarly make it soon. Obtaining mutants for these glycoproteins using these techniques is easy and fast, Fig. 4. The AGPs genetic redundancy allows the complementarity of these two techniques [14, 94]. In addition, it is possible to create a higher order mutant by the two techniques at the same time, in case double or triple knockout are not viable. Since most of the AGPs still do not have their function characterized, the application of these two techniques will be of great importance.

The best approaches to obtaining AGPs knockdown or knockout mutants by RNAi and CRISPR/Cas9 methods, respectively. To obtain RNAi mutants, first it is necessary to design an amiRNA in the WMD3 platform. After the chimeric sequence is designed, it is then transferred to a vector of choice using a Gateway cloning system. Lastly, the construction is transferred into A. thaliana by the Floral Dip method and the seeds transformed are selected. When the plants start to grow the genetic techniques such as PCR and RT-qPCR may be used for confirmation of gene knockdown. For the CRISPR/Cas9 technique, the first step is to design the single guide RNA (sgRNA) with 20 nt (blue) and PAM sequence (red) in one of various online platforms (in this case, are shown two sgRNAs for target gene). The sgRNAs may be cloned into a binary vector which contains a Cas9 promotor, being ready to receive the sgRNAs. Multiple sgRNA expression cassettes can be cloned using a Golden Gate assembly (BsaI - IIS restriction enzyme). After cloning, A. thaliana plants may be transformed by the Floral Dip method and the seeds can be selected by red fluorescence (ex. pKAMA-ITACHI Red [83]). When the plants start to grow the genetic techniques such as PCR and Sequencing may be used for confirmation of gene knockout. (Color figure online)

Conclusion

In recent years, the AGPs have been strong candidates for the performance of various functions in the most varied processes of plant development, especially in the reproductive process, from the development of gametophytes to pollen-pistil interactions, culminating in fertilization and seed formation. However, the mode of action and signaling cascade of most AGPs is still to be unveiled.

Now is the time to unlock the functions of these glycoproteins by taking advantage of these new technologies, gene silencing and genome editing, such as RNAi and CRISPR/Cas9. In this review, it was clear that the two techniques are vital in studies with AGPs. The CRISPR/Cas9 revolutionized current biology, as it is a robust, simple and efficient technology that has opened a new door to genome editing. Several plant biology research groups already use this technology for distinct purposes, with the main goal of increasing and improving agricultural productivity in the future. The application of CRISPR/Cas9 in the AGPs study, will allow to better understand the roles of these essential plant glycoproteins. The work developed for decades, by RNAi, grants that this technique continues to be essential to unravel the function of several genes, such as AGPs. The combination and comparison of results between these two techniques will be valuable in the future, especially in large families of genes as AGPs, where functional redundancy often is a problem.

References

Schultz CJ, Rumsewicz MP, Johnson KL, Jones BJ, Gaspar YM, Bacic A (2002) Using genomic resources to guide research directions. The Arabinogalactan protein gene family as a test case. Plant Physiol 129:1448–1463

Borner GHH, Lilley KS, Stevens TJ, Dupree P (2003) Identification of glycosylphosphatidylinositol—anchored proteins in Arabidopsis. A proteomic and genomic analysis. Plant Physiol 132:568–577

Nguema-Ona E, Vicre-Gibouin M, Gotte M, Plancot B, Lerouge P et al (2014) Cell wall O-glycoproteins and N-glycoproteins: aspects of biosynthesis and function. Front Plant Sci 5:12

Pereira AM, Pereira LG, Coimbra S (2015) Arabinogalactan proteins: rising attention from plant biologists. Plant Reprod 28:1–15

Showalter AM, Keppler B, Lichtenberg J, Gu DZ, Welch LR (2010) A bioinformatics approach to the identification, classification, and analysis of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins. Plant Physiol 153:485–513

Schultz C, Gilson P, Oxley D, Youl J, Bacic A (1998) GPI-anchors on arabinogalactan-proteins: implications for signalling in plants. Trends Plant Sci 3:426–431

Showalter AM (2001) Arabinogalactan-proteins: structure, expression and function. Cell Mol Life Sci 58:1399–1417

Majewska-Sawka A, Nothnagel EA (2000) The multiple roles of arabinogalactan proteins in plant development. Plant Physiol 122:3–9

Seifert GJ, Roberts K (2007) Annual review of plant biology, vol. 58, Annual reviews, Palo Alto, pp 137–161

Ellis M, Egelund J, Schultz CJ, Bacic A (2010) Arabinogalactan-proteins (AGPs): key regulators at the cell surface? Plant Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.110.156000

Nguema-Ona E, Coimbra S, Vicre-Gibouin M, Mollet JC, Driouich A (2012) Arabinogalactan proteins in root and pollen-tube cells: distribution and functional aspects. Ann Bot 110:383–404

Nguema-Ona E, Vicre-Gibouin M, Cannesan MA, Driouich A (2013) Arabinogalactan proteins in root-microbe interactions. Trends Plant Sci 18:445–454

Pereira AM, Lopes AL, Coimbra S (2016) Arabinogalactan proteins as interactors along the crosstalk between the pollen tube and the female tissues. Front Plant Sci 7:15

Coimbra S, Costa M, Jones B, Mendes MA, Pereira LG (2009) Pollen grain development is compromised in Arabidopsis agp6 agp11 null mutants. J Exp Bot 60:3133–3142

Basu D, Liang Y, Liu X, Himmeldirk K, Faik A et al (2013) Functional identification of a hydroxyproline-O-galactosyltransferase specific for Arabinogalactan protein biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 288:10132–10143

Basu D, Tian L, Wang WD, Bobbs S, Herock H et al (2015) A small multigene hydroxyproline-O-galactosyltransferase family functions in arabinogalactan-protein glycosylation, growth and development in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol 15:23

Basu D, Wang WD, Ma SY, DeBrosse T, Poirier E et al (2015) Two hydroxyproline galactosyltransferases, GALT5 andGALT2, function in Arabinogalactan-protein glycosylation, growth and development in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 10:36

Ogawa-Ohnishi M, Matsubayashi Y (2015) Identification of three potent hydroxyproline O-galactosyltransferases in Arabidopsis. Plant J 81:736–746

Su SH, Higashiyama T (2018) Arabinogalactan proteins and their sugar chains: functions in plant reproduction, research methods, and biosynthesis. Plant Reprod 31:67–75

Schultz CJ, Johnson KL, Currie G, Bacic A (2000) The classical arabinogalactan protein gene family of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12:1751–1767

Barrangou R, Birmingham A, Wiemann S, Beijersbergen RL, Hornung V, Smith AV (2015) Advances in CRISPR-Cas9 genome engineering: lessons learned from RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res 43:3407–3419

Chuang CF, Meyerowitz EM (2000) Specific and heritable genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:4985–4990

Fire A, Xu SQ, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC (1998) Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 91:806–811

Belhaj K, Chaparro-Garcia A, Kamoun S, Patron NJ, Nekrasov V (2015) Editing plant genomes with CRISPR/Cas9. Curr Opin Biotechnol 32:76–84

Novina CD, Sharp PA (2004) The RNAi revolution. Nature 430:161–164

Napoli C, Lemieux C, Jorgensen R (1990) Introduction of a chimeric chalcone synthase gene into petunia results in reversible co-suppression of homologous genes in trans. Plant Cell 2:279–289

Van der Krol AR, Mur LA, Beld M, Mol J, Stuitje AR (1990) Flavonoid genes in petunia: addition of a limited number of gene copies may lead to a suppression of gene expression. Plant Cell 2:291–299

Ruiz MT, Voinnet O, Baulcombe DC (1998) Initiation and maintenance of virus-induced gene silencing. Plant Cell 10:937–946

Angell SM, Baulcombe DC (1997) Consistent gene silencing in transgenic plants expressing a replicating potato virus X RNA. Embo J 16:3675–3684

Dougherty WG, Lindbo JA, Smith HA, Parks TD, Swaney S, Proebsting WM (1994) RNA-mediated virus-resistance in transgenic plants—exploitation of a cellular pathway possibly involved in RNA degradation. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 7:544–552

Kumagai MH, Donson J, Dellacioppa G, Harvey D, Hanley K, Grill LK (1995) Cytoplasmic inhibition of carotenoid biosynthesis with virus-derived RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:1679–1683

Hannon GJ (2002) RNA interference. Nature 418:244–251

Baulcombe D (2004) RNA silencing in plants. Nature 431:356–363

Ossowski S, Schwab R, Weigel D (2008) Gene silencing in plants using artificial microRNAs and other small RNAs. Plant J 53:674–690

Schwab R, Ossowski S, Riester M, Warthmann N, Weigel D (2006) Highly specific gene silencing by artificial microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18:1121–1133

Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP (2004) Computational identification of plant MicroRNAs and their targets, including a stress-induced miRNA. Mol Cell 14:787–799

Hammond SM, Bernstein E, Beach D, Hannon GJ (2000) An RNA-directed nuclease mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells. Nature 404:293–296

Kurihara Y, Watanabe Y (2004) Arabidopsis micro-RNA biogenesis through Dicer-like 1 protein functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:12753–12758

Watson JM, Fusaro AF, Wang MB, Waterhouse PM (2005) RNA silencing platforms in plants. Febs Lett 579:5982–5987

Schwab R, Palatnik JF, Riester M, Schommer C, Schmid M, Weigel D (2005) Specific effects of MicroRNAs on the plant transcriptome. Dev Cell 8:517–527

Alvarez JP, Pekker I, Goldshmidt A, Blum E, Amsellem Z, Eshed Y (2006) Endogenous and synthetic microRNAs stimulate simultaneous, efficient, and localized regulation of multiple targets in diverse species. Plant Cell 18:1134–1151

Niu QW, Lin SS, Reyes JL, Chen KC, Wu HW et al (2006) Expression of artificial microRNAs in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana confers virus resistance. Nat Biotechnol 24:1420–1428

Parizotto EA, Dunoyer P, Rahm N, Himber C, Voinnet O (2004) In vivo investigation of the transcription, processing, endonucleolytic activity, and functional relevance of the spatial distribution of a plant miRNA. Genes Dev 18:2237–2242

Zeng Y, Wagner EJ, Cullen BR (2002) Both natural and designed micro RNAs technique can inhibit the expression of cognate mRNAs when expressed in human cells. Mol Cell 9:1327–1333

Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116:281–297

Acosta-Garcia G, Vielle-Calzada JP (2004) A classical arabinogalactan protein is essential for the initiation of female gametogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16:2614–2628

Levitin B, Richter D, Markovich I, Zik M (2008) Arabinogalactan proteins 6 and 11 are required for stamen and pollen function in Arabidopsis. Plant J 56:351–363

Li J, Yu MA, Geng LL, Zhao J (2010) The fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein gene, FLA3, is involved in microspore development of Arabidopsis. Plant J 64:482–497

Pereira AM, Nobre MS, Pinto SC, Lopes AL, Costa ML et al (2016) "Love Is strong, and you're so sweet": Jagger Is essential for persistent synergid degeneration and polytubey block in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant 9:601–614

Hou YN, Guo XY, Cyprys P, Zhang Y, Bleckmann A et al (2016) Maternal ENODLs are required for pollen tube reception in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 26:2343–2350

Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E (2012) A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337:816–821

Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA (2012) RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature 482:331–338

Kumar V, Jain M (2015) The CRISPR-Cas system for plant genome editing: advances and opportunities. J Exp Bot 66:47–57

Tsai SQ, Joung JK (2016) Defining and improving the genome-wide specificities of CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases. Nat Rev Genet 17:300–312

Deltcheva E, Chylinski K, Sharma CM, Gonzales K, Chao YJ et al (2011) CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature 471:602

Makarova KS, Haft DH, Barrangou R, Brouns SJJ, Charpentier E et al (2011) Evolution and classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:467–477

Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ (2008) CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in Staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science 322:1843–1845

Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F (2013) Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoco 8:2281–2308

Jiang FG, Doudna JA (2017) In: Dill KA (ed) Annual review of biophysics, vol 46. Palo Alto, Annual reviews, pp 505–529

Doudna JA, Charpentier E (2014) The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346:1077

Lowder LG, Zhang DW, Baltes NJ, Paul JW, Tang X et al (2015) A CRISPR/Cas9 toolbox for multiplexed plant genome editing and transcriptional regulation. Plant Physiol 169:971–985

Tang X, Zheng X, Qi Y, Zhang D, Cheng Y et al (2016) A single transcript CRISPR-Cas9 system for efficient genome editing in plants. Mol Plant 9:1088–1091

Rouet P, Smih F, Jasin M (1994) Introduction of double-strand breaks into the genome of mouse cells by expression of a rare-cutting endonuclease. Mol Cell Biol 14:8096–8106

Choulika A, Perrin A, Dujon B, Nicolas JF (1995) Induction of homologous recombination in mammalian chromosomes by using the i-scei system of saccharomyces-cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 15:1968–1973

Unniyampurath U, Pilankatta R, Krishnan MN (2016) RNA interference in the age of CRISPR: will CRISPR interfere with RNAi? Int J Mol Sci 17:15

Qi YP, Zhang Y, Baller JA, Voytas DF (2016) Histone H2AX and the small RNA pathway modulate both non-homologous end-joining and homologous recombination in plants. Mutat Res Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen 783:9–14

Demirci Y, Zhang B, Unver T (2018) CRISPR/Cas9: an RNA-guided highly precise synthetic tool for plant genome editing. J Cell Physiol 233:1844–1859

Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S et al (2013) DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol 31:827

Fu YF, Foden JA, Khayter C, Maeder ML, Reyon D et al (2013) High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol 31:822

Guschin DY, Waite AJ, Katibah GE, Miller JC, Holmes MC, Rebar EJ (2010) Engineered zinc finger proteins. Springer, Berlin, pp 247–256

Arora L, Narula A (2017) Gene editing and crop improvement using CRISPR-Cas9 system. Front Plant Sci 8:1932

Feng Z, Zhang B, Ding W, Liu X, Yang DL et al (2013) Efficient genome editing in plants using a CRISPR/Cas system. Cell Res 23:1229

Li JF, Norville JE, Aach J, McCormack M, Zhang D et al (2013) Multiplex and homologous recombination–mediated genome editing in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana using guide RNA and Cas9. Nat Biotechnol 31:688

Nekrasov V, Staskawicz B, Weigel D, Jones JD, Kamoun S (2013) Targeted mutagenesis in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana using Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol 31:691

Shan Q, Wang Y, Li J, Zhang Y, Chen K et al (2013) Targeted genome modification of crop plants using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat Biotechnol 31:686

Miao J, Guo D, Zhang J, Huang Q, Qin G et al (2013) Targeted mutagenesis in rice using CRISPR-Cas system. Cell Res 23:1233

Xing HL, Dong L, Wang ZP, Zhang HY, Han CY et al (2014) A CRISPR/Cas9 toolkit for multiplex genome editing in plants. BMC Plant Biol 14:327

Engler C, Gruetzner R, Kandzia R, Marillonnet S (2009) Golden gate shuffling: a one-pot DNA shuffling method based on type IIs restriction enzymes. PLoS ONE 4:e5553

Ma X, Zhang Q, Zhu Q, Liu W, Chen Y et al (2015) A robust CRISPR/Cas9 system for convenient, high-efficiency multiplex genome editing in monocot and dicot plants. Mol Plant 8:1274–1284

Engler C, Kandzia R, Marillonnet S (2008) A one pot, one step, precision cloning method with high throughput capability. PLoS ONE 3(e3647):80

Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA III, Smith HO (2009) Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods 6:343

Wang ZP, Xing HL, Dong L, Zhang HY, Han CY et al (2015) Egg cell-specific promoter-controlled CRISPR/Cas9 efficiently generates homozygous mutants for multiple target genes in Arabidopsis in a single generation. Genome Biol 16:144

Tsutsui H, Higashiyama T (2017) pKAMA-ITACHI vectors for highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 58:46–56

Lee JH, Skowron PM, Rutkowska SM, Hong SS, Kim SC (1996) Sequential amplification of cloned DNA as tandem multimers using class-IIS restriction enzymes. Genet Anal 13:139–145

Padgett KA, Sorge JA (1996) Creating seamless junctions independent of restriction sites in PCR cloning. Gene 168:31–35

Gelvin SB (2003) Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation: the biology behind the “gene-jockeying” tool. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:16–37

Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16:735–743

Bechtold N, Jolivet S, Voisin R, Pelletier G (2003) The endosperm and the embryo of Arabidopsis thaliana are independently transformed through infiltration by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Transgenic Res 12:509–517

Desfeux C, Clough SJ, Bent AF (2000) Female reproductive tissues are the primary target of Agrobacterium-Mediated transformation by the Arabidopsis floral-dip method. Plant Physiol 123:895–904

Boettcher M, McManus MT (2015) Choosing the right tool for the job: RNAi, TALEN, or CRISPR. Mol Cell 58:575–585

Wang HY, Yang H, Shivalila CS, Dawlaty MM, Cheng AW et al (2013) One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell 153:910–918

Doench JG, Fusi N, Sullender M, Hegde M, Vaimberg EW et al (2016) Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol 34:184

Doench JG, Hartenian E, Graham DB, Tothova Z, Hegde M et al (2014) Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nat Biotechnol 32:1262–U1130

Cutler S, McCourt P (2005) Dude, where's my phenotype? Dealing with redundancy in signaling networks. Plant Physiol 138:558–559

Acknowledgements

The work described in this review was supported by the EU project 690946 - SexSeed - Sexual Plant reproduction - Seed Formation, funded by H2020-MSCA-RISE-2015; European Union’s MSCA-IF-2016 Ana Marta Pereira - under grant agreement No. 753328; FCT PhD grant of Ana Lúcia Lopes, SFRH/BD/115960/2016; FCT PhD grant of Diana Moreira, SFRH/BD/143557/2019.

Funding

EU Horizon 2020 SexSeed RISE programme: Grant Agreement No. 690946.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed equally to the writing of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this review was written in the absence of any potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moreira, D., Pereira, A.M., Lopes, A.L. et al. The best CRISPR/Cas9 versus RNA interference approaches for Arabinogalactan proteins’ study. Mol Biol Rep 47, 2315–2325 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-020-05258-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-020-05258-0