Abstract

Chronic boredom is associated with many negative psychological outcomes, including undermining perceived meaning in life. Meanwhile, emerging research suggests that spontaneous self-affirmation, that is, an inclination to self-affirm, is linked to greater well-being and buffers against psychological threats. We investigated the relationship between spontaneous self-affirmation, perceptions of meaning in life, and boredom proneness with four correlational studies. Study 1a (N = 166) demonstrated that people inclined to self-affirm experience greater perceptions of meaning in life. Study 1b (N = 170) confirmed that spontaneous self-affirmation is associated with lower levels of boredom proneness. Study 2a (N = 214) and Study 2b (N = 105) provided evidence for our central hypothesis, showing that spontaneous self-affirmation predicts lower levels of boredom proneness via greater perceptions of meaning in life. These findings confirm that elevating meaning in life through psychological resources, like spontaneous self-affirmation, may limit boredom. Our work extends the emerging well-being benefits of spontaneous self-affirmation, by demonstrating associations with higher meaning in life and lower boredom proneness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Positive affirmations have invaded the mainstream. The practice of affirming positive statements via journaling, meditation, or verbal repetition is intended to challenge negative self-beliefs and engender a positive self-image. While this practice is partly rooted in the New Thought and New Age movements (e.gs., Byrne, 2006; Carnegie, 1936; Haye, 1984; Hicks & Hicks, 2006; Vincent Peale, 1952) that gained popularity in the second half of the twentieth century, positive affirmations are now widely established via social media and performed by ‘Gen Z’ and ‘Millennials’. For instance, the TikTok trend, “Lucky Girl Syndrome”, went viral on TikTok in January 2023. The trend encouraged users to recite daily affirmations such as “I am so lucky” and “Everything always works out for me” with the promise that repeating these positive statements will bring good fortune. Despite the widespread popularity of affirmations, the science behind them (and the lack thereof) has been heavily questioned (e.g. Gormon, 2023). While the material benefits of “Lucky Girl Syndrome” might be slightly beyond the scope of evidence-based psychological research, self-affirmation theory (Steele, 1988) and related research have extensively demonstrated the psychological benefits of affirming the self in response to threats over the last 30 years (Cohen & Sherman, 2014; McQueen & Klein, 2006).

The frequent practice of repeating affirmations would suggest that people can develop a propensity to self-affirm in response to threats and challenges over time. Recently, researchers have begun to study individual inclinations to self-affirm to capture such habits (Harris et al., 2019). Indeed, the tendency to respond to psychological threats with self-affirming cognitions (Harris et al., 2019; Pietersma & Dijkstra, 2012) may offer ample psychological benefits. Boredom is a common and negative experience, accompanied by low feelings of meaning, that can be highly problematic for well-being in its chronic form (i.e. boredom proneness; Fahlman et al., 2009; Goldberg et al., 2011; Pfattheicher et al., 2021; Van Tilburg et al., 2019b). In the current research, we proposed that spontaneous self-affirmation may serve as a psychological resource to buffer against boredom by increasing perceptions of meaning in life.

Boredom: A psychological threat

Boredom is an unpleasant emotion involving feeling unchallenged (Van Tilburg & Igou, 2012), meaningless (Van Tilburg & Igou, 2011), unengaged (Eastwood et al., 2012), and like time is passing slowly (Danckert & Allman, 2005). Momentary experiences of boredom occur quite frequently (Chin et al., 2017) and can provoke both undesirable (e.g. non-suicidal self-injury, Nederkoorn et al., 2016) and desirable (e.g. prosocial intentions, Van Tilburg & Igou, 2017b) outcomes. Meanwhile, being susceptible to boredom, typically referred to as boredom proneness, comes with dire consequences for well-being (e.gs., Fahlman et al., 2009; Goldberg et al., 2011). Boredom proneness is a trait-like construct, reflecting individual differences in the frequency of being bored, the intensity of boredom, and general perceptions of life being boring (Tam et al., 2021; Van Tilburg et al., 2024).

Research consistently demonstrates the negative consequences of boredom proneness for psychological and physical well-being. For instance, boredom proneness is associated with increased depression and anxiety symptoms (Fahlman et al., 2009; Goldberg et al., 2011), aggressive tendencies (Pfattheicher et al., 2021; Van Tilburg et al., 2019b), loneliness (Skues et al., 2016), lower levels of intrinsic motivation (Pekrun et al., 2010), and a lack of physical exercise (Wolff et al., 2021). Boredom proneness is also linked to problematic behaviors with negative societal implications, such as risk-taking (Kılıç et al., 2020), impulsivity (Cao & An, 2020; Moynihan et al., 2017), binge drinking (Biolcati et al., 2016), and online trolling (Thacker & Griffiths, 2012). In context, boredom proneness can lead to poorer supervisor ratings of job performance in the workplace (Watt & Hargis, 2010), predict more cheating behaviors (Blais et al., 2023) and negatively impact student engagement and performance in educational settings (Sharp et al., 2020). Evidently, boredom proneness is a problematic dispositional tendency. It appears to impede healthy psychological functioning and is associated with many societal harms.

While research has demonstrated the negative consequences of boredom proneness, little is known about how proneness to boredom can be reduced and prevented. Our perspective starts with the notion that boredom is a psychological threat, as it calls into question our sense of personal meaning and significance (Van Tilburg & Igou, 2012). Perceiving one’s life to be meaningful is a core psychological need (Heine et al., 2006; Igou & Van Tilburg, 2021; Moynihan et al., 2021). Thus, threats to meaning can be threats to our self-integrity. Understanding this essential facet of boredom proneness is crucial for the conceptualization of psychological processes that are suitable for containing boredom proneness. We propose that individual differences to self-affirm in response to threats are particularly suited for inhibiting boredom proneness. People are proposed to self-affirm in response to a threat to their self-integrity (i.e. a psychological threat). This psychological threat arises from the perception of an external challenge to the adequacy of the self (Cohen & Sherman, 2014; Steele, 1988). As we outline below, self-affirmation is an effective resource for alleviating the impact of psychologically threatening information, thus we propose that it is aptly matched to protect against the psychological threat that boredom evokes.

Self-affirmation: A psychological resource

According to self-affirmation theory, people have a fundamental need to maintain a positive self-image and protect their self-integrity (Steele, 1988). Self-affirmation procedures originated as an experimental method developed by Steele and colleagues (Steele, 1988; Steele & Liu, 1983). The most used self-affirmation manipulation involves affirming an important value to the individual and explaining why it is important to them (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). This procedure counteracts the negative impact of threats to the perceived integrity of the self by demonstrating one’s adequacy (Steele, 1988). Subsequent work shows that individuals can also self-affirm by reflecting on their personal strengths (McQueen & Klein, 2006) and positive social relationships (e.g. Cai et al., 2013). This line of research suggests that self-affirmation manipulations have important psychological implications, such as buffering against threats and reliably reducing defensive responses to psychologically threatening information (for reviews, see McQueen & Klein, 2006; Sherman & Cohen, 2006). There are also psychological gains of self-affirmation. For example, self-affirmed participants appear to experience less stress and worry than their non-affirmed counterparts (Sherman et al., 2009).

The mechanisms underlying the benefits of self-affirmation have been disputed. Self-affirmation theory suggests that writing about important values bolsters the self, leading to these psychological benefits. However, value-based affirmation does not seem to increase self-esteem (Crocker et al., 2008; Schmeichel & Martens, 2005). Rather, researchers have proposed that affirming important values may enable self-transcendence by reminding individuals about what they care about beyond themselves, which consequently increases feelings of love and connection (Burson et al., 2012; Crocker et al., 2008; Lindsay & Creswell, 2014). Consistently, self-affirmation promotes higher levels of construal, allowing individuals to take an abstract, broader perspective of a challenging event or stimulus (Schmeichel & Vohs, 2009).

Much self-affirmation research to date has focused on experimental manipulations. However, some individuals are also likely to be naturally inclined to self-affirm in the face of psychologically threatening information. To address this gap, researchers have begun to investigate individual differences in the propensity to self-affirm in everyday life (Harris et al., 2019; Pietersma & Dijkstra, 2012). These individual differences to self-affirm in response to psychological threats have been referred to as cognitive self-affirmation inclination (Pietersma & Dijkstra, 2012) and, more recently, spontaneous self-affirmation (Harris et al., 2019). We adopt the latter term. By spontaneous self-affirmation, Harris et al. (2019) characterize self-affirmation as an individual’s naturally occurring response to a perceived psychological threat. They proposed the Spontaneous Self-Affirmation Measure (SSAM) to measure this construct. The scale represents three sources people use to self-affirm, reflecting on personal strengths and attributes, important values, and social relationships. When their self-integrity feels threatened, individuals may spontaneously remind themselves of these aspects of their life that affirm a positive view of the self.

Given the plethora of benefits associated with self-affirmation inductions, a dispositional tendency to self-affirm is likely to be a valuable and adaptive psychological trait. Emerging research suggests that this indeed might be the case. Spontaneous self-affirmation, like induced self-affirmation, is associated with positive psychological outcomes and can promote self-esteem, habitual positive self-thought, well-being, adaptive coping, and less depression and anxiety (Harris et al., 2019, 2022; Jessop et al., 2022). However, given the recent development of a psychometric measurement of this construct, much remains to be discovered about the correlates and potential implications of this individual difference and if the benefits of induced self-affirmation also extend to spontaneous self-affirmation.

Spontaneous self-affirmation versus boredom proneness: The role of meaning in life

Perceiving that one’s life is meaningful is a central human need (Baumeister, 1991; Heine et al., 2006) and is considered vital for well-being (e.g. Zika & Chamberlain, 1992). Despite definitional ambiguity surrounding the construct of meaning in life, researchers have generally arrived at the consensus that a meaningful life involves feeling that one’s life makes sense (coherence), is imbued with purpose, and has significance (Costin & Vignoles, 2020; King et al., 2006; Steger, 2012). Self-affirmation manipulations typically involve affirming what values are most meaningful in people’s lives (e.g. Schmeichel & Martens, 2005). Thus, self-affirmation and meaning perceptions are closely related. Pursuing goals that align with personal values leads to greater meaning in life (McGregor & Little, 1998); thus, being reminded of meaningful values should naturally boost perceptions of meaning in life. Indeed, a two-week self-affirmation intervention that focused on values increased perceptions of meaning in life (Nelson et al., 2014). Similarly, affirming individual strengths and social relationships will boost meaning in life through self-esteem and belongingness needs, according to the Meaning Maintenance Model (Heine et al., 2006). We propose that individuals who are inclined to self-affirm will also perceive their lives to be more meaningful.

There is initial evidence to suggest that spontaneous self-affirmation will increase perceptions of meaning in life. Spontaneous self-affirmation predicts eudaimonic well-being, cross-sectionally and longitudinally (Jessop et al., 2022), and eudaimonic well-being focuses on the experience of a meaningful life (Ryan & Deci, 2001). However, while self-affirmation theory is centered around affirming what is meaningful to the individual, the relationship between spontaneous self-affirmation and meaning in life has not yet been empirically demonstrated. We addressed this void as part of our larger investigation.

Boredom proneness is consistently associated with lower perceptions of meaning in life, and meaninglessness is a distinctive characteristic of boredom (e.g. Chan et al., 2018; Igou & Van Tilburg, 2021; O'Dea et al., 2022; Van Tilburg & Igou, 2017a). Thus, boredom serves as a psychological threat by evoking feelings of meaninglessness. Emerging research has begun to demonstrate how individual differences that support increased perceptions of meaning in life predict lower boredom proneness (Coughlan et al., 2019; O'Dea et al., 2022; Van Tilburg et al., 2019a). For example, O'Dea et al., 2022 found that individuals with high levels of self-compassion (compassion towards one’s own suffering) are less prone to boredom, and this relationship was mediated by greater levels of perceived meaning in life. Notably, self-affirmation has been shown to increase feelings of self-compassion (Lindsay & Creswell, 2014). As previously mentioned, the Meaning Maintenance Model (Heine et al., 2006) proposes that strengthening meaning through psychological resources, like self-affirmation, can buffer against threats to the self. Self-affirmation reliably buffers against psychological threats and promotes meaning sources (Harris et al., 2022; Lindsay & Creswell, 2014; McQueen & Klein, 2006; Sherman & Cohen, 2006). We thus propose that spontaneous self-affirmation will predict less boredom proneness via higher levels of meaning in life.

Overview

Boredom proneness is a trait-like psychological tendency associated with a myriad of negative well-being outcomes (Tam et al., 2021; Van Tilburg et al., in press). Understanding the predictors and mechanisms associated with the experience is vital to conceptualise how this trait-like experience can be reduced and prevented. Boredom proneness is accompanied by perceptions of low meaning (O'Dea et al., 2022; Van Tilburg & Igou, 2012), meanwhile self-affirmation is a method of bolstering meaning (Heine et al., 2006; Nelson et al., 2014; Schmeichel & Martens, 2005). Thus, we hypothesise that spontaneous self-affirmation, an adaptive psychological tendency (Harris et al., 2022), will predict lower levels of boredom proneness via greater perceptions of meaning in life. We proposed and tested the notion that an inclination to self-affirm will be positively associated with meaning in life (Study 1a) and negatively related to boredom proneness (Study 1b). In Studies 2a and 2b, we tested our central hypothesis, that the relationship between spontaneous self-affirmation and boredom proneness would be mediated by greater perceptions of meaning in life. We conducted four studies to systematically test our hypotheses across different procedures and samples. All studies received ethical approval from the Education and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of Limerick and were programmed via Qualtrics. Data and materials are openly available at https://osf.io/7r4b2/?view_only=319f664876aa464e87e12711e21937da.

Studies 1a and 1b

First, we set out to establish the direct relationship between our variables of interest. In Study 1a, we hypothesised that spontaneous self-affirmation would be positively associated with perceptions of meaning in life. In Study 1b, we hypothesised that spontaneous self-affirmation would be negatively associated with boredom proneness.

Methods

Study 1a

Participants and design

There were 166 participants recruited on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk; https://www.mturk.com/) to complete the study in return for payment. We required 109 participants to have a power of (1–β) = 0.90 (Faul et al., 2007) assuming a correlation of r = 0.30, adopting a Type-I error of α = 0.05 (two-tailed). We exceeded this sample size to account for online dropouts. Ten participants were automatically removed from the study after failing the initial attention check, leaving 156 participants in the final sample (81 women, 75 men; Mage = 23.19, SDage = 12.46). Most of the sample were US American (96%; 1 Asian, 1 Canadian, 1 Dominican, 1 Italian, 2 Native American, 1 Russian).

Procedure and materials

After giving informed consent, participants completed an attention check where they were required to indicate what they were asked to do in the study. Participants who answered incorrectly (“Read an article about the impact of nature on fitness”) were excluded from the analysis. Demographic details regarding age, gender, and nationality were collected. The tendency to self-affirm was measured using the Spontaneous Self-Affirmation Measure (SSAM; Harris et al., 2019), a 13-item scale with three subscales reflecting strengths (4 items), values (4 items), and social relations (5 items). Participants responded to these items on a scale of 1 (disagree completely) to 7 (agree completely; ω = 0.95; e.g. “When I find myself feeling threatened or anxious by people or events, I find myself thinking about my strengths”). Presence of meaning in life was measured using the 5-item Presence of Meaning in Life subscale from the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MP-MLQ; Steger et al., 2006), e.g. “I understand my life’s meaning”, with one reverse-scored item “My life has no clear purpose” (1 = absolutely untrue, 7 = absolutely true; ω = 0.93). Participants were then thanked, debriefed, and rewarded for their participation.

Study 1b

Participants and design

Again, we required 109 participants to have a power of (1–β) = 0.90 (Faul et al., 2007), assuming a correlation of r = 0.30, adopting a Type-I error of α = 0.05 (two-tailed). We recruited 170 participants on MTurk for the study; however, 16 failed the initial attention check and were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 154 (72 women, 82 men; Mage = 24.06, SDage = 13.55). The majority of the sample were US American in nationality (95%, 1 Asian, 1 Middle Eastern, 2 Native American, 1 Russian, 1 Spanish, 1 Turkish).

Procedure and materials

Participants gave informed consent, completed the attention check, and reported demographic details as in Study 1a. The tendency to self-affirm was measured using the same measure as Study 1a (ω = 0.95). Boredom proneness was measured using the Short Boredom Proneness Scale (BPS Short Form; Farmer & Sundberg, 1986; Struk et al., 2017; ω = 0.93), an 8-item scale (e.g. “I often find myself at “loose ends”, not knowing what to do”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Once the measures were completed, participants were thanked, debriefed, and rewarded for their participation.

Results and discussion

Study 1a

Spontaneous self-affirmation was positively correlated with meaning in life (Table 1). This finding supports our hypothesis that individuals who are inclined to self-affirm in response to psychological threats experience greater meaning in life. Next, we examined the relationship between spontaneous self-affirmation and boredom proneness.

Study 1b

The correlation between boredom proneness and the inclination to self-affirm in response to threats was negative and significant (Table 1). This result supports our hypothesis that individuals inclined to self-affirm are less prone to boredom.

After Studies 1a and 1b confirmed that spontaneous self-affirmation is linked to both meaning in life and boredom, we developed a test of our mediational model, namely that spontaneous self-affirmation predicts lower levels of boredom through a greater sense of meaning in life, in Studies 2a and 2b.

Studies 2a and 2b

Studies 2a and 2b investigated the mediating role of meaning in life from spontaneous self-affirmation to boredom proneness. Specifically, we hypothesised that spontaneous self-affirmation would be negatively associated with boredom proneness via perceptions of meaning in life. To replicate our findings, we conducted a study identical in method to Study 2a with Irish undergraduate students (Study 2b).

Method

Study 2a

Participants and design

We required 136 participants to have a power of (1–β) = 0.90 to detect indirect effects with a serial mediator (Schoemann et al., 2017), assuming correlations of r = 0.40, estimated with 1000 replications using 20,000 Monte-Carlo draws and assuming a Type-I error of α = 0.05 (two-tailed). We exceeded that sample size in accounting for potential dropouts associated with online studies. There were 267 participants initially recruited on MTurk, but 53 were automatically excluded after the attention check. Thus, there were 214 participants in the final sample (101 women, 114 men; Mage = 23.51, SDage = 11.12; 98% US American; 1 Asian, 1 Malaysian, 2 Native American, 1 Pakistani).

Procedure and materials

As in Study 1a and Study 1b, participants offered informed consent, completed the attention check, and reported demographic details. They then completed the same measures of spontaneous self-affirmation (ω = 0.96), presence of meaning in life (ω = 0.85), and boredom proneness (ω = 0.94) used in the studies above. Participants also completed another measure of boredom proneness, the Harthouse Boredom Proclivity Scale (HBPS; Van Tilburg et al., 2019a; ω = 0.95), a four-item scale (e.g. “How prone are you to feeling bored?”; 1 = never, 7 = all the time). The final item differed in response by asking “Specifically, how often do you feel bored?” (1 = once or twice a year, 7 = at least once a day). This was to ensure that the relationship between self-affirmation and boredom was robust across different boredom measures (O’Dea et al., 2022), especially since the boredom proneness scale faces some challenges regarding its validity (Van Tilburg et al., 2024). The measures were presented in random order to control for potential order effects. Once the study was complete, participants were thanked, debriefed, and rewarded for their participation.

Study 2b

Participant and design

We recruited 120 undergraduate students from the University of Limerick in return for course credit. We recruited as many participants as possible from this limited participant pool of students, but we aimed for at least 100. After failing the attention check, 15 students were automatically excluded, resulting in an effective sample of 105 participants, yielding a power of (1–β) = 0.86 to detect indirect effects with a serial mediator (Schoeman et al., 2017), assuming correlations of r = 0.40, estimated with 1000 replications using 20,000 Monte-Carlo draws and assuming a Type-I error of α = 0.05 (two-tailed). The sample consisted of 36 males, 68 females, and one ‘other’ who were between 18 and 47 years of age (Mage = 19.90, SDage = 3.44). The majority of the participants were Irish (85.7%; 3 US American, 2 English; 2 French 1 Brazilian, 1 Emirati; 1 Polish; 1 Saudi; 1 Swiss).

Procedure and materials

The procedure was identical to Study 2a. Spontaneous self-affirmation (ω = 0.93), presence of meaning in life (ω = 0.91), and boredom proneness (BPS Short Form, ω = 0.90, and HBPS, ω = 0.93) were measured in the same manner as Study 2a. After successfully completing the survey, participants were awarded course credit via SONA, the university’s research participation website.

Results and discussion

Study 2a

The HBPS and BPS Short Form were combined to form one boredom proneness index (BPI) given their high correlation, r = 0.78, p < 0.001. As can be seen in Table 2, there was a positive relationship between spontaneous self-affirmation and meaning in life, replicating Study 1a. There was a negative relationship between perceptions of meaning in life and boredom proneness, as expected. However, there was a positive relationship between an inclination to self-affirm and boredom proneness, contradicting the findings of Study 1b.

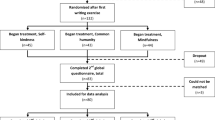

To test our mediational model, we used PROCESS (Hayes, 2021; Model 4) with robust standard errors (HC3) and 10,000 bootstraps. We entered spontaneous self-affirmation as the predictor, presence of meaning in life as mediator, and boredom proneness as the outcome variable. Spontaneous self-affirmation positively predicted meaning in life, B = 0.555, SE = 0.081, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.394, 0.715]. Meaning presence was significantly negatively associated with boredom proneness, B = − 0.596, SE = 0.104, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.801, − 0.391]. The total effect of spontaneous self-affirmation on boredom proneness was significant and positive, B = 0.292, SE = 0.078, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.138, 0.445]. It was comprised of a significant direct effect of spontaneous self-affirmation on boredom proneness, B = 0.622, SE = 0.090, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.446, 0.799], and, crucially, a significant negative indirect effect through meaning presence, B = − 0.331, SE = 0.082, 95% CI [− 0.510, − 0.189] (see Fig. 1). This supports our hypothesis that individuals inclined to self-affirm are less prone to boredom as they experience greater meaning in life.

Study 2b

Akin to Study 2a, the HBPS and BPS Short Form were highly correlated, r = 0.75, p < 0.001, and combined to form a BPI index. As can be seen in Table 2, spontaneous self-affirmation correlates positively with perceptions of meaning in life and negatively with boredom proneness, consistent with Study 1b but contradicting Study 2a. Again, we find a negative relationship between perceptions of meaning in life and boredom proneness.

Using PROCESS Model 4 (Hayes, 2021) with robust standard errors (HC3) and 10,000 bootstraps, we tested the mediational model as in Study 2a. Spontaneous self-affirmation significantly positively predicted meaning in life, B = 0.400, SE = 0.107, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.188, 0.613], while meaning presence was significantly negatively associated with boredom proneness, B = − 0.282, SE = 0.082, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.444, − 0.119]. The total effect of spontaneous self-affirmation on boredom proneness was significant and negative, B = − 0.247, SE = 0.082, p = 0.003, 95% CI [− 0.410, − 0.084]. The direct effect of spontaneous self-affirmation on boredom proneness was not significant, B = − 0.134, SE = 0.077, p = 0.08, 95% CI [− 0.287, 0.018]. Importantly, there was a significant negative indirect effect through meaning presence, B = − 0.123, SE = 0.045, 95% CI [− 0.214, − 0.037] (see Fig. 2). This adds further support to our hypothesis that individuals inclined to self-affirm are less prone to boredom as they experience greater meaning in life.

General discussion

Boredom represents a psychological threat as it features an appraised lack of meaning in one’s situation or life in general (Barbalet, 1999; Chan et al., 2018; Van Tilburg & Igou, 2012, 2017a). Spontaneous self-affirmation is an individual difference that buffers against psychological threats and is likely to increase perceptions of meaning (Harris et al., 2019; Jessop et al., 2022). We hypothesized and found that spontaneous self-affirmation is associated with greater perceptions of meaning in life and, consequently, lower boredom proneness. These four studies provide evidence for the prediction that individuals inclined to self-affirm in response to perceived threat have greater perceptions of meaning in life (Study 1a, Study 2a, & Study 2b) and, consequently, are less prone to boredom (Studies 2a and 2b).

In Study 1a, Study 2a, and Study 2b, spontaneous self-affirmation consistently predicted greater levels of meaning in life, supporting our hypotheses. This suggests that individuals inclined to self-affirm in the face of threats via their values, strengths, or social relationships, perceive their lives to be more meaningful. Given that perceiving one’s life to be meaningful is considered vital for well-being (Zika & Chamberlain, 1992), this positive association is consistent with the emerging research demonstrating the psychological benefits of spontaneous self-affirmation (Harris et al., 2019; Jessop et al., 2022). This relationship also supports the extended self-affirmation literature, which finds that affirming important values can bolster meaning and buffer against psychological threats (e.g. Hales et al., 2016; Nelson et al., 2014; Schmeichel & Martens, 2005).

Crucially, Study 2a and 2b confirm our hypothesis that spontaneous self-affirmation predicts lower levels of boredom proneness via greater perceptions of meaning in life. That is, we found a significant negative indirect effect of spontaneous self-affirmation on boredom proneness through meaning in life in both studies. These results confirm that spontaneous self-affirmation is associated with greater perceptions of meaning in life which in turns predicts lower levels of boredom proneness. Individuals with a tendency to self-affirm in response to a threat have elevated levels of meaning in life, which makes them less vulnerable to boredom. This finding further supports the notion that spontaneous self-affirmation is an adaptive individual difference that can buffer against psychological threats. In addition, this research strengthens the theoretical proposition that perceptions of meaning in life are central to regulating boredom (Chan et al., 2018; Van Tilburg & Igou, 2011, 2012).

The link between boredom and low perceptions of meaning is well-established. More recently, research has demonstrated how augmenting meaning through various meaning sources can buffer against boredom experiences (Coughlan et al., 2019; O’Dea et al., 2022; Van Tilburg et al., 2019a). Increasing meaning appears to be an effective means of ameliorating boredom and its negative consequences. Particularly germane to the present research, Coughlan et al. (2019) found that participants who affirmed heroes experienced higher levels of meaning in life and lower levels of boredom proneness. We found that a trait inclination to affirm the self has similar relationships with meaning and boredom. Evidently, meaning in life is a crucial variable to incorporate when trying to understand and regulate boredom experiences. As aforementioned, boredom proneness is associated with detrimental well-being (e.g. elevated depression symptoms; Goldberg et al., 2011) and social outcomes (e.g. sadistic aggression; Pfattheicher et al., 2021). While empirical research has extensively demonstrated these negative implications, relatively little is known about how we can avoid chronic boredom. Given the prevalence of boredom, this research has broad practical implications for individuals in a range of settings, including education and the workplace. By fostering perceptions of meaning in life, spontaneous self-affirmation may be an adaptive psychological quality for reducing and preventing chronic boredom.

Study 1b and Study 2b confirmed a negative relationship between spontaneous self-affirmation and boredom proneness. Harris et al. (2019) raised the possibility that those higher in spontaneous self-affirmation may experience the world as less threatening, which would support a negative relationship between boredom proneness and spontaneous self-affirmation. However, Study 2a found a positive zero-order correlation between the two variables. This was surprising given that chronic boredom negatively impacts well-being (e.g. Fahlman et al., 2009), while spontaneous self-affirmation has been proposed to contribute to well-being (Jessop et al., 2022). It may be that individuals who are prone to boredom, accompanied by lower perceptions of meaning (Igou & Van Tilburg, 2021; Moynihan et al., 2021), have, over time, become inclined to self-affirm in response to this threat as an adaptive strategy, lending to a positive correlation. The difference may also be, in part, attributed to the characteristics of the samples. Descriptive analyses suggest that the US sample (Study 2a) had better psychological well-being (higher meaning and self-affirmation levels and lower boredom proneness) than the Irish undergraduate sample (Study 2b). Cultural or age differences may have impacted these findings, which would be an interesting topic for further investigation. We found predominant evidence (Study 1b and Study 2b) to suggest that the relationship between these variables is, in general, more likely to be negative. However, the relationship between these constructs is likely complex, and several factors may be underlying their relation not addressed in the current investigation.

Consistent with the self-transcendence perspective on the mechanisms underlying self-affirmation (e.g. Crocker et al., 2008), spontaneous self-affirmation may also activate positive other-directed feelings like love and connection, strong sources of meaning in life (Baumeister, 1991; King & Hicks, 2021). As aforementioned, Lindsay and Creswell (2014) find that a self-affirmation manipulation activates feelings of increased self-compassion. Moreover, they find that self-affirmation specifically enhances self-compassion for individuals with low levels of trait self-compassion, consistent with the idea that self-affirmation can boost deficient psychological resources. Spontaneous self-affirmation may be a means through which these positive emotions are activated. Future research should investigate if spontaneous self-affirmation promotes these emotions, as a state or trait, and consequently, bolsters meaning in life. These variables may further explain the relationship between self-affirmation and boredom proneness and the conflicting correlations we find between Study 1b, Study 2a, and Study 2b.

The presented research has some limitations. Notably, the findings presented in this article are based on cross-sectional, correlational evidence and are limited to individual differences in self-affirmation, meaning in life, and boredom proneness. Causal claims about their relation cannot be made and the mediation model is affected similarly. These findings provide a basis for future research to examine the causal effects of self-affirmation on boredom. For instance, Nelson et al. (2014) found that a brief self-affirmation manipulation can boost perceptions of meaning in daily life, and self-affirmation interventions have been demonstrated to boost feelings of connectedness and belonging (Crocker et al., 2008; Hales et al., 2016), core aspects of what makes life meaningful (Baumeister, 1991; Hicks & King, 2009). Perceptions of meaning in life may be a causal mechanism through which self-affirmation promotes ample positive psychological outcomes such as less boredom.

Self-affirmation interventions may be an efficacious strategy for combatting both chronic and state boredom. Individuals can experience momentary instances of boredom without necessarily being prone to boredom (Elpidorou, 2014). Therefore, the utility of a self-affirmation manipulation for combatting state boredom also has practical relevance. Experimental, experience sampling, and longitudinal studies are needed to establish causality towards the development of interventions. There are likely several effective strategies to address chronic boredom (e.g. addressing attentional failures, Eastwood et al., 2012); addressing meaning perceptions is one such theoretically and empirically supported strategy. Drawing on the control-value theory of achievement emotions (Pekrun, 2006), affirming the perceived value of an activity for the self is likely to prevent and reduce boredom (Pekrun et al., 2010). Tailored value-affirmation interventions may be an effective tool for combatting boredom in applied settings. An investment into boredom mitigation strategies is essential for the well-being of both the individual and society.

In addition, the studies presented here rely on samples predominantly composed of US American participants. While we aspired to address this shortcoming by replicating our findings with an Irish sample (Study 2b), further testing of the hypotheses in non-Western samples is necessary to generalise our findings to other cultures and nationalities. Given the apparent novelty of the empirical study of spontaneous self-affirmation, cultural differences in the tendency to self-affirm have not yet been examined and may be present (as discussed above). We may expect that collective and individualistic cultures will experience psychological threats differently. For instance, in collectivist cultures, internal attributes are less integrated to one’s self-integrity than the individuals’ social roles and relationships (Heine & Lehman, 1997). Thus, cultural differences may moderate the way one spontaneously self-affirms. Lastly, future research may wish to use a common factor model with latent variables to further test the validity of the relationship between the variables.

Conclusion

Boredom proneness is linked to various psychological, physical, and behavioral issues, including low perceptions of meaning in life. Spontaneous self-affirmation has the potential to foster adaptive outcomes and defend against everyday psychological threats. Consistently, our results suggest that spontaneous self-affirmation is associated with an increase in perceptions of meaning in life and a decrease in boredom proneness. These findings have important research and practical implications. Individuals who are inclined to self-affirm through various sources (strengths, values, social relationships) benefit from feelings of meaning and less boredom. Spontaneous self-affirmation may prove a useful individual difference in coping with chronic boredom, although specific experimental and intervention research is needed to confirm this notion. While spontaneous self-affirmation cannot guarantee the physical manifestations of all your desires (as “Lucky Girl Syndrome” may suggest), our findings, in line with prior research, confirm that it can offer valuable psychological benefits.

Data availability

Data and materials for all studies are openly available at https://osf.io/7r4b2/?view_only=319f664876aa464e87e12711e21937da.

References

Barbalet, J. M. (1999). Boredom and social meaning. The British Journal of Sociology, 50(4), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.1999.00631.x

Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Meanings of life. NY: Guilford press.

Biolcati, R., Passini, S., & Mancini, G. (2016). “I cannot stand the boredom”. Binge drinking expectancies in adolescence. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 3, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2016.05.001

Blais, J., Fazaa, G. R., & Mungall, L. R. (2023). A pre-registered examination of the relationship between psychopathy, boredom-proneness, and University-level cheating. Psychological Reports. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941231184385

Burson, A., Crocker, J., & Mischkowski, D. (2012). Two types of value-affirmation: Implications for self-control following social exclusion. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(4), 510–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611427773

Byrne, R. (2006). The Secret. Simon & Schuster.

Cai, H., Sedikides, C., & Jiang, L. (2013). Familial self as a potent source of affirmation: Evidence from China. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(5), 529–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612469039

Cao, Q., & An, J. (2020). Boredom proneness and aggression among people with substance use disorder: The mediating role of trait anger and impulsivity. Journal of Drug Issues, 50(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042619886822

Carnegie, D. (1936). How to win friends and influence people. Simon & Schuster.

Chan, C. S., Van Tilburg, W. A. P., Igou, E. R., Poon, C. Y. S., Tam, K. Y. Y., Wong, V. U., & Cheung, S. K. (2018). Situational meaninglessness and state boredom: Cross-sectional and experience-sampling findings. Motivation and Emotion, 42(4), 555–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9693-3

Chin, A., Markey, A., Bhargava, S., Kassam, K. S., & Loewenstein, G. (2017). Bored in the USA: Experience sampling and boredom in everyday life. Emotion, 17(2), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000232

Cohen, G. L., & Sherman, D. K. (2014). The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 333–371. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115137

Costin, V., & Vignoles, V. L. (2020). Meaning is about mattering: Evaluating coherence, purpose, and existential mattering as precursors of meaning in life judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(4), 864–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000225

Coughlan, G., Igou, E. R., Van Tilburg, W. A. P., Kinsella, E. L., & Ritchie, T. D. (2019). On boredom and perceptions of heroes: A meaning-regulation approach to heroism. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 59(4), 455–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167817705281

Crocker, J., Niiya, Y., & Mischkowski, D. (2008). Why does writing about important values reduce defensiveness? Self-affirmation and the role of positive other-directed feelings. Psychological Science, 19(7), 740–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02150.x

Danckert, J. A., & Allman, A. A. A. (2005). Time flies when you’re having fun: Temporal estimation and the experience of boredom. Brain and Cognition, 59(3), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2005.07.002

Eastwood, J. D., Frischen, A., Fenske, M. J., & Smilek, D. (2012). The unengaged mind: Defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(5), 482–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612456044

Elpidorou, A. (2014). The bright side of boredom. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1245. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01245

Fahlman, S. A., Mercer, K. B., Gaskovski, P., Eastwood, A. E., & Eastwood, J. D. (2009). Does a lack of life meaning cause boredom? Results from psychometric, longitudinal, and experimental analyses. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(3), 307–304. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2009.28.3.307

Farmer, R., & Sundberg, N. D. (1986). Boredom proneness–the development and correlates of a new scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 50(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5001_2

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Goldberg, Y. K., Eastwood, J. D., LaGuardia, J., & Danckert, J. (2011). Boredom: An emotional experience distinct from apathy, anhedonia, or depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(6), 647–666. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2011.30.6.647

Gormon, A. (2023, January 16). TikTok’s Lucky Girl Syndrome isn’t new – and it has a dark side. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/jan/17/tiktoks-lucky-girl-syndrome-isnt-new-and-it-has-a-dark-side

Hales, A. H., Wesselmann, E. D., & Williams, K. D. (2016). Prayer, self-affirmation, and distraction improve recovery from short-term ostracism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 64, 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.01.002

Harris, P. R., Griffin, D. W., Napper, L. E., Bond, R., Schüz, B., Stride, C., & Brearley, I. (2019). Individual differences in self-affirmation: Distinguishing self-affirmation from positive self-regard. Self and Identity, 18(6), 589–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2018.1504819

Harris, P. R., Richards, A., & Bond, R. (2022). Individual differences in spontaneous self-affirmation and mental health: relationships with self-esteem, dispositional optimism and coping. Self and Identity. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2022.2099455

Haye, L. (1984). You can heal your life. Hay House.

Hayes, A. F. (2021). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). NY: Guilford publications.

Heine, S. J., & Lehman, D. R. (1997). Culture, dissonance, and self-affirmation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(4), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297234005

Heine, S. J., Proulx, T., & Vohs, K. D. (2006). The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 88–110. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_1

Hicks, E., & Hicks, J. (2006). The law of attraction: The basics of the teachings of Abraham. New York: Hay House Inc.

Hicks, J. A., & King, L. A. (2009). Positive mood and social relatedness as information about meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271108

Igou, E. R. & Van Tilburg, W. A. P. (2021). The existential sting of boredom: Implications for moral judgments and behavior. In A. Elpidorou (Ed.), The moral psychology of boredom (pp. 57–78). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN-10:178661538X

Jessop, D. C., Harris, P. R., & Gibbons, T. (2022). Individual differences in spontaneous self-affirmation predict well-being. Self and Identity. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2022.2079711

Kılıç, A., Van Tilburg, W. A., & Igou, E. R. (2020). Risk-taking increases under boredom. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 33(3), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2160

King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2021). The science of meaning in life. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 561–584. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-072420-122921

King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L., & Del Gaiso, A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179

Lindsay, E. K., & Creswell, J. D. (2014). Helping the self help others: Self-affirmation increases self-compassion and pro-social behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 421. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00421

McGregor, I., & Little, B. R. (1998). Personal projects, happiness, and meaning: On doing well and being yourself. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 494–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.494

McQueen, A., & Klein, W. M. (2006). Experimental manipulations of self-affirmation: A systematic review. Self and Identity, 5(4), 289–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860600805325

Moynihan, A. B., Igou, E. R., & van Tilburg, W. A. (2017). Boredom increases impulsiveness. Social Psychology, 48(5), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000317

Moynihan, A. B., Igou, E. R., & van Tilburg, W. A. (2021). Existential escape of the bored: A review of meaning-regulation processes under boredom. European Review of Social Psychology, 32(1), 161–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2020.1829347

Moynihan, A. B., Tilburg, W. A. V., Igou, E. R., Wisman, A., Donnelly, A. E., & Mulcaire, J. B. (2015). Eaten up by boredom: Consuming food to escape awareness of the bored self. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1), 369. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00369

Nederkoorn, C., Vancleef, L., Wilkenhöner, A., Claes, L., & Havermans, R. C. (2016). Self-inflicted pain out of boredom. Psychiatry Research, 237, 127–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.063

Nelson, S. K., Fuller, J. A., Choi, I., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). Beyond self-protection: Self-affirmation benefits hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(8), 998–1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214533389

O’Dea, M. K., Igou, E. R., van Tilburg, W. A., & Kinsella, E. L. (2022). Self-compassion predicts less boredom: The role of meaning in life. Personality and Individual Differences, 186, 111360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111360

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Daniels, L. M., Stupnisky, R. H., & Perry, R. P. (2010). Boredom in achievement settings: Exploring control–value antecedents and performance outcomes of a neglected emotion. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019243

Pfattheicher, S., Lazarević, L. B., Westgate, E. C., & Schindler, S. (2021). On the relation of boredom and sadistic aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(3), 573–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000335

Pietersma, S., & Dijkstra, A. (2012). Cognitive self-affirmation inclination: An individual difference in dealing with self-threats. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466610X533768

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Schmeichel, B. J., & Martens, A. (2005). Self-affirmation and mortality salience: Affirming values reduces worldview defense and death-thought accessibility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(5), 658–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271567

Schmeichel, B. J., & Vohs, K. (2009). Self-affirmation and self-control: Affirming core values counteracts ego depletion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 770–782. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014635

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617715068

Sharp, J. G., Sharp, J. C., & Young, E. (2020). Academic boredom, engagement and the achievement of undergraduate students at university: A review and synthesis of relevant literature. Research Papers in Education, 35(2), 144–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2018.1536891

Sherman, D. K., Bunyan, D. P., Creswell, J. D., & Jaremka, L. M. (2009). Psychological vulnerability and stress: The effects of self-affirmation on sympathetic nervous system responses to naturalistic stressors. Health Psychology, 28(5), 554–562. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014663

Sherman, D. K., & Cohen, G. L. (2006). The psychology of self-defense: Self-affirmation theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 183–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38004-5

Skues, J., Williams, B., Oldmeadow, J., & Wise, L. (2016). The effects of boredom, loneliness, and distress tolerance on problem internet use among university students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14, 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9568-8

Steele, C. M. (1988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 21, 261–302. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60229-4

Steele, C. M., & Liu, T. J. (1983). Dissonance processes as self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.5

Steger, M. F. (2012). Making meaning in life. Psychological Inquiry, 23(4), 381–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2012.720832

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Kaler, M., & Oishi, S. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

Stillman, T. F., Baumeister, R. F., Lambert, N. M., Crescioni, A. W., DeWall, C. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). Alone and without purpose: Life loses meaning following social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.007

Struk, A. A., Carriere, J. S. A., Cheyne, J. A., & Danckert, J. (2017). A short boredom proneness scale: Development and psychometric properties. Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115609996

Tam, K. Y., Van Tilburg, W. A., & Chan, C. S. (2021). What is boredom proneness? A comparison of three characterizations. Journal of Personality, 89(4), 831–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12618

Thacker, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012). An exploratory study of trolling in online video gaming. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning, 2(4), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijcbpl.2012100102

Van Tilburg, W. A. P., Moynihan, A. B., Chan, C. S., & Igou, E. R. (2024). Boredom proneness. In M. Bieleke, W. Wolff, & C. Martarelli (Eds.), Handbook of boredom research (pp. 191–210). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003271536-15

Van Tilburg, W. A., & Igou, E. R. (2011). On boredom and social identity: A pragmatic meaning-regulation approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(12), 1679–1691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211418530

Van Tilburg, W. A. P., & Igou, E. R. (2012). On boredom: Lack of challenge and meaning as distinct boredom experiences. Motivation and Emotion, 36(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9234-9

Van Tilburg, W. A. P., & Igou, E. R. (2017a). Boredom begs to differ: Differentiation from other negative emotions. Emotion, 17(2), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000233

Van Tilburg, W. A., & Igou, E. R. (2017b). Can boredom help? Increased prosocial intentions in response to boredom. Self and Identity, 16(1), 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2016.1218925

Van Tilburg, W. A., Igou, E. R., Maher, P. J., & Lennon, J. (2019b). Various forms of existential distress are associated with aggressive tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences, 144(1), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.032

Van Tilburg, W. A., Igou, E. R., Maher, P. J., Moynihan, A. B., & Martin, D. G. (2019a). Bored like Hell: Religiosity reduces boredom and tempers the quest for meaning. Emotion, 19(2), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000439

Vincent Peale, N. (1952). The power of positive thinking: A practical guide to mastering the problems of everyday living. Prentice Hall.

Watt, J. D., & Hargis, M. B. (2010). Boredom proneness: Its relationship with subjective underemployment, perceived organizational support, and job performance. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9138-9

Wolff, W., Bieleke, M., Stähler, J., & Schüler, J. (2021). Too bored for sports? Adaptive and less-adaptive latent personality profiles for exercise behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 53, 101851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101851

Zika, S., & Chamberlain, K. (1992). On the relation between meaning in life and psychological well-being. British Journal of Psychology, 83(1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1992.tb02429.x

Acknowledgements

All authors consented to the submission of this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Research involving human/animal participants

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants followed the institutional research committee's ethical standards and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Dea, M.K., Igou, E.R. & van Tilburg, W.A.P. Spontaneous self-affirmation predicts more meaning and less boredom. Motiv Emot 48, 237–247 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-024-10060-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-024-10060-7