Abstract

Why do dimensions of perfectionism have different effects on employees’ engagement, exhaustion, and job satisfaction? Combining the perfectionism literature and self-determination theory, we expected self-oriented perfectionism (SOP) and socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP) to be differently related to employee well-being through the fulfilment or lack of autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction. We attributed a unique role to autonomy satisfaction in fostering work engagement. Data were collected at 2 time points, with a 3-month interval, in an online study. Several results from path analyses including data from 328 (T1) and 138 (T2) employees were consistent with our expectations. SPP was negatively related to work engagement and job satisfaction via a lack of autonomy satisfaction and positively related to exhaustion via a lack of relatedness satisfaction. Additionally, SOP and SPP showed different associations with competence satisfaction. Overall, our findings highlight the motivational differences inherent in perfectionism that translate into well-being via need satisfaction and unique effects of the three needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Perfectionism has been described as a “double-edged sword” that contains both adaptive and maladaptive aspects (Molnar et al., 2006). This personality disposition affects all areas of life, with the workplace being the most frequently affected domain (Stoeber & Stoeber, 2009). Given this ambivalence and the increase of perfectionism in industrialized countries (Curran & Hill, 2019), research on perfectionism in the workplace has flourished in recent years (Ocampo et al., 2020). We now have wide knowledge about dimensional perfectionism and its positive and negative work-related outcomes, especially regarding well-being. According to recent reviews and a meta-analysis (Harari et al., 2018; Ocampo et al., 2020; Stoeber & Damian, 2016), perfectionism dimensions summarized as perfectionistic strivings (e.g. self-oriented perfectionism, personal standards, and high standards) may show a positive link to well-being, such as work engagement. By contrast, dimensions belonging to perfectionistic concerns (e.g. socially prescribed perfectionism, concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, and discrepancy) consistently show a maladaptive association with well-being, such as burnout. It is often debated whether perfectionistic strivings can be considered as adaptive (Stoeber & Otto, 2006). These dimensions have also been found to be linked to negative outcomes, such as negative affective and cognitive reactions after failure (Besser et al., 2004), and associations with positive outcomes often emerge when the overlap with perfectionistic concerns is controlled for (Hill et al., 2010).

However, knowledge of the mechanisms that drive these different effects is limited (Ocampo et al., 2020). Such knowledge is necessary to advance the theory and more clearly understand how the dimensions of perfectionism may contribute to high vitality and optimal functioning, or exhaustion and poor functioning. Furthermore, knowledge of the relevant mechanisms would help to deal with perfectionism and can be used to improve interventions to promote employee well-being, given that perfectionism can be considered as a stable disposition (e.g. Sherry et al., 2013). Drawing on transactional stress theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and the initiation-termination model of worry (Berenbaum, 2010), previous research identified maladaptive coping and rumination about work as processes that mediate the relationship between perfectionistic concerns and negative indicators of well-being, such as burnout (Flaxman et al., 2018; Stoeber & Damian, 2016). These specific mechanisms may fall short in explaining why employees high in perfectionistic strivings tend to fully invest themselves in their work.

Thus, we aim to integrate dimensional perfectionism in a broader theoretical framework that considers its fundamental motivational differences and how these may translate into high or low functioning and well-being at work. We argue that self-determination theory (SDT) and specifically its concept of basic need satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 2000) offers a promising approach. A core tenet of SDT is that satisfaction of the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness is essential for flourishing and well-being, including in the workplace (Broeck et al., 2016). The dimensions of perfectionism have different motivational properties which should affect the way employees orient themselves to their work environment and their behaviour, cognitions, and emotions in different situations. Thus, we expect that the dimensions of perfectionism should differ in the extent to which individuals find opportunities to satisfy their needs within this context. Against this background, we propose perfectionism as a form of dispositional motivation in the SDT framework and investigate the mediating role of need satisfaction in the relationship between dimensional perfectionism and employees’ job satisfaction, exhaustion, and work engagement.

This study contributes to previous research in three ways. First, concerning research on perfectionism, we extend existing knowledge about perfectionism and overall need satisfaction (e.g. Jowett et al., 2016) as we consider the different associations between the dimensions of perfectionism and satisfaction of the three needs. We investigate autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction as separate mechanisms that link perfectionism to employee well-being. We thus contribute to a more detailed understanding of mechanisms that link the dimensions of perfectionism to both poor and high well-being and address these motivational mechanisms in the workplace context.

Second, our study contributes to research on SDT. Specifically, it extends the SDT literature in two ways: By focusing on perfectionism as an individual difference variable, we highlight the active role of individuals in shaping need satisfaction. Research on SDT in the workplace has emphasized the relevance of contextual factors, such as job design, leadership, or compensation, for employees’ need satisfaction and well-being (e.g., Manganelli et al., 2018). We agree with this relevance, but also argue that other important sources, such as personality dispositions, have to be considered to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the antecedents of need satisfaction at work. In addition, we attribute a unique position to autonomy satisfaction in fostering optimal, active functioning at work (i.e. work engagement). Thus, we specify the assumption of SDT that each need contributes uniquely to psychological growth and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000) by investigating which needs will predict which well-being indicators.

Dimensional perfectionism and employee well-being

Broadly, perfectionism is conceived of as a personality disposition. It is characterized by striving for flawlessness and having exceptionally high performance standards, in combination with the tendency to evaluate one’s own behaviour overcritically (Flett & Hewitt, 2002; Frost et al., 1990). The double-edged nature of perfectionism in driving various effects on well-being can be traced back to the dimensionality of the construct. One way of distinguishing these dimensions is to consider the source and direction of the perfectionistic standards (Hewitt & Flett, 1991). Self-oriented perfectionism (SOP) is intrapersonal in nature and comprises holding exceedingly high standards for oneself, accompanied by strict evaluations of one’s own behaviour. Socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP) is characterized by the belief that others impose high standards, and that those others will be strongly critical if one fails to meet their expectations. Lastly, other-oriented perfectionism (OOP) describes holding exceedingly high demands that are directed towards others.

In the course of growing research interest, various models with different conceptualizations of these dimensions have evolved (e.g. Frost et al., 1990; Hewitt & Flett, 1991). These models have in common that the proposed dimensions can be assigned to two superordinate factors. They are typically referred to as perfectionistic strivings, which refers to aspects such as setting high performance standards; and perfectionistic concerns, meaning aspects such as the fear of negative evaluation and concern over mistakes (see Stoeber & Otto, 2006, for a comprehensive review). SOP is seen as a key indicator of perfectionistic strivings, whereas SPP is seen as a key indicator of perfectionistic concerns (Stoeber & Damian, 2016; Stoeber & Gaudreau, 2017). OOP is considered as an ‘other form’ of perfectionism as findings challenge its assignment to these superordinate factors (Ocampo et al., 2020). Following recommendations concerning this third dimension (Stoeber & Otto, 2006), we refrained from including OOP in the present study.Footnote 1 Hence, we focus on SOP and SPP as key indicators of perfectionism by examining their associations with employee well-being.

Overall, we adopted the traditional definition of well-being in the workplace as a broad concept encompassing many constructs (Danna & Griffin, 1999). We build on the theoretical framework by Warr (1990, 2013) to capture employee well-being comprehensively, with positive and negative indicators. This framework of affective well-being entails four quadrants which differ on the dimensions of pleasure and activation. We focused on job satisfaction (low activation, high pleasure), exhaustion (low activation, low pleasure), and work engagement (high activation, high pleasure) because these indicators correspond to Warr’s framework (Bakker & Oerlemans, 2011). They also represent frequently studied and established indicators of employee well-being (e.g. Bhave et al., 2019; Mäkikangas et al., 2016) and indicate differences in functioning among perfectionistic employees. To date, SPP (but not SOP) has been related to poor job satisfaction (Fairlie & Flett, 2003; Hochwarter & Byrne, 2010) and high levels of exhaustion. By contrast, SOP is unrelated to exhaustion and may even display negative associations with exhaustion when the overlap between the dimensions of perfectionism is controlled for (see also Stoeber & Damian, 2016, for a review). Moreover, a negative association for SPP and a positive association for SOP and work engagement was found (Childs & Stoeber, 2010). Mirroring the pattern of the negative relationship of SOP and exhaustion, the negative relationship of SPP and work engagement emerges or becomes more evident when the overlap between the dimensions is statistically controlled for (see again Stoeber & Damian, 2016, also for the relevance of considering this overlap in the investigation of perfectionism).

Self-determination theory and basic need satisfaction as a theoretical framework

According to self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 2000), individuals are naturally active and strive towards psychological growth and well-being. Within SDT, basic psychological needs are described as universal “nutriments” and necessary conditions for the natural processes to function optimally (Deci & Ryan, 2000). SDT posits the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Building on previous work (e.g. deCharms, 1968), Deci and Ryan (2000) understand autonomy as a sense of freedom and ownership over one’s behaviour and the feeling that behaviours are concordant with the self. In line with White (1959), they describe competence as the desire to experience mastery over one’s environment and to attain valuable outcomes. Lastly, relatedness refers to the fundamental human need to feel connected with and cared for by others (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). The focus of SDT is that the satisfaction of these needs has similar, positive effects on flourishing and well-being for each individual. Before considering these positive effects in more detail, we will look at factors that may facilitate or hinder need satisfaction.

SDT has been applied to a variety of contexts encompassing education, sports, and work, considering that individuals are embedded in and interact with their social environment (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Conditions in these environments, such as supervisor support provided in the workplace, are one important factor that may contribute to need satisfaction (Deci et al., 2017). We argue that individuals themselves also contribute to the experience of need satisfaction and thus play an active role within SDT. In line with this argument, SDT addresses individual differences that determine how individuals orient toward aspects of the environment as another antecedent of need satisfaction at work (Deci et al., 2017). These relatively enduring differences are typically referred to as causality orientations and describe the source of initiating and regulating behaviour and thus the degree of experiencing behaviour as self-determined (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Individuals with a high autonomy orientation show interest and high self-initiation, whereas the behavior of individuals with a control orientation is guided by external contingencies and what others demand. In a sample of employees, Baard et al. (2004) found that both autonomy causality orientation as an individual difference and perceived autonomy support as a contextual variable were independently related to experiencing need satisfaction.

Even more explicitly, motive disposition theory (McClelland, 1985) and the extended two process model (Schüler et al., 2019) address individual differences in the energization of behaviour and the preference for “wanting” certain experiences as natural incentives. Especially the motive dispositions for achievement and affiliation which are understood as results of an individual’s development and learning are closely intertwined with need satisfaction. In a series of studies, Sheldon and Schüler (2011) demonstrated that individuals with motive dispositions towards achievement and affiliation reported actually having experiences of the corresponding needs for competence and relatedness, concluding that “wanting” certain experiences leads to “having” these experiences. However, wanting experiences more than others should be considered as independent of needing autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction for well-being (Sheldon & Schüler, 2011).

Another important distinction is that motive dispositions include hope and fear components that explain why individuals exhibit different behaviour, cognition, and emotion in situations relevant to that motive disposition (Schüler et al., 2019): Achievement encompasses the components of hope for success and fear of failure, and affiliation includes hope for closeness and fear of rejection (McClelland, 1985). The hope and fear components are theorized to be differently related to approaching desired outcomes and avoiding undesired outcomes (Trash & Hurst, 2008), and thus guide behaviours that are differently successful in satisfying needs (Schüler et al., 2019). Specifically, Schüler et al. (2019) argue that the concepts of fear and avoidance might contrast with an individual’s natural tendency towards growth and development based in SDT.

To emphasize a salient motivational component of perfectionism, we argue that the perfectionism dimensions differ in the source of perfectionistic demands and the degree to which the behaviour is experienced as self-determined as well as the experiences they seek (“wanting”). Thus, we propose perfectionism as a further antecedent of need satisfaction and a dispositional form of motivation. In line with recent recommendations (Van den Broeck et al., 2016), we treated the three needs as related yet separate constructs and investigated their distinct relationships with perfectionism. In the following section, we will derive the first set of hypotheses related to the differential associations between perfectionism and need satisfaction (Hypotheses 1–3). Subsequently, we will continue to describe basic need satisfaction as an underlying mechanism between perfectionism and well-being and derive the second set of hypotheses regarding the proposed indirect effects (Hypotheses 4–9).

Perfectionism and basic need satisfaction

We argue that the double-edged nature of perfectionism also drives differences in need satisfaction. Different motivational qualities rooted in SOP and SPP (Stoeber et al., 2018) should affect the way employees orient toward their workplace environment and behave, think, and feel in motive-relevant situations and thus the degree to which they find opportunities to satisfy their needs within this context. Whereas self-oriented perfectionists strive to fulfil their own and inherently valued standards, socially prescribed perfectionists experience external pressure to perform perfectly (Hewitt & Flett, 1991). Thus, the causality orientations characterizing the dimensions is more likely to be autonomous and more self-determined for SOP and controlled for SPP. According to the dual process model of perfectionism (Slade & Owens, 1998), self-oriented perfectionists are generally driven by approach behaviour; hence, they pursue perfection, success, and approval as goals. By contrast, socially prescribed perfectionists are inclined to be driven by avoidance behaviour; their goal is to avoid imperfection, failure, and disapproval. These distinct goals are entwined with the hope and fear components of dispositional motives (hope for success and fear of failure, hope for closeness and fear of rejection). We argue that the approach goals pursued by self-oriented perfectionists are, on the whole, consistent with an individual’s natural tendency towards growth and development, and thus likely to channel behaviours favourable for need satisfaction. Guided by avoidance goals, socially prescribed perfectionists will, unfortunately without wanting to, engage in behaviours that hinder need satisfaction.

Research supports the notion that the dimensions of perfectionism have different motivational qualities and demonstrates the value of investigating perfectionism from a SDT perspective (e.g. Moore et al., 2018). Evidence suggests that the motivation associated with SOP is mainly autonomous and approach-orientated whereas the motivation relating to SPP is overall controlled motivation and avoidance-oriented (see Stoeber et al., 2018, for a review). In the following, we aim to provide a more detailed argumentation concerning perfectionism and its relationship with satisfaction of the three needs at work.

According to SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1985) and differences in causality orientations, individuals high in SOP are likely to orient towards workplace environments that allow them to take responsibility for their behaviour and to seek jobs and tasks where they can demonstrate self-initiation and strive towards their high standards. This orientation should facilitate the experience of autonomy satisfaction. Individuals high in SPP, on the other hand, are likely to be more attuned to external controls, such as rewards and the demands of others, than to their own will and interests. Thus, they are likely to seek jobs that meet the expectations of others such as family or friends (e.g., high pay), feel pressurized, and thus hesitate to proactively engage in activities. In addition, they should place high importance on aligning to supervisors, colleagues or clients’ demands when conducting tasks, constantly aiming to avoid failure and disapproval. Therefore, they should experience a lack of autonomy satisfaction.

H1

SOP is positively related (a) and SPP is negatively related (b) to autonomy satisfaction.

Given their autonomy orientation, employees high in SOP can be expected to actively seek out jobs and tasks that are challenging and allow them to make progress towards their own high demands. Employees high in SPP, by contrast, should not only find themselves in less challenging jobs but also avoid challenging tasks. They may be constantly confronted with the anxiety about not meeting the unrealistic high expectations of others and their own inadequacy to fulfil these expectations. In addition, they may have difficulties in deriving satisfaction, even from successful tasks, as they believe that the result will be not good enough. This line of reasoning can be supported by assumptions of the two-process model (Sheldon & Schüler, 2011). A strong motive disposition for achievement (“wanting” certain experiences), which is highly salient in both SOP and SPP, should enable “having” competence satisfaction. However, given that different hope and fear components predominate, employees high in SOP and those high in SPP should exhibit different behaviours, cognitions, and emotions in the same motive-relevant situation (Schüler et al., 2019): Fearing and also expecting to fall short of others’ demands, employees high in SPP might engage less in a new work task or even avoid the task to avoid failure. They would handicap themselves in terms of experiencing of competence. Hoping to succeed, employees high in SOP may engage in the same new work task, master the task, and experience competence satisfaction. Supporting these arguments, research has linked SOP to task approach goals, task mastery, self-efficacy, and satisfaction and pride after high performance and SPP to fear of negative evaluations, task failure, procrastination, low self-efficacy, and dissatisfaction after high performance (Flett et al., 1992; Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Mills & Blankstein, 2000; Stoeber & Yang, 2010; Stoeber et al., 2015).

H2

SOP is positively related (a) and SPP is negatively related (b) to competence satisfaction.

Furthermore, differences in relatedness satisfaction can be hypothesized. Concerning social interactions, an autonomy orientation will facilitate relatedness satisfaction through active engagement in one’s social context and natural, honest social interactions, whereas a control orientation may lead to defensive functioning (Hodgins et al., 1996). Employees high in SOP should feel more related to their supervisors and colleagues and experience them as comparatively supportive. Socially-prescribed perfectionists, on the contrary, should feel rather disconnected from others at work, perceiving others as overly demanding and displaying constant effort to maintain a perfect outward appearance. The latter aspect is captured in the concept of perfectionistic self-presentation which describes an interpersonal expression of perfectionism that is related to inauthentic expressions of the self, anxiety in social interactions, and social self-esteem deficits (Hewitt et al., 2003).

Perfectionism has been described as developing in response to finding a sense of affiliation and connection with others, combined with the assumption that appearing to be perfect ensures mattering to others and approval from others (Hewitt et al., 2017). Thus, there is a link to the motive disposition for affiliation. Again, different hope and fear components dominate which should result in different behaviour that is differently successful in satisfying the need for relatedness. We argue that the pursuit of others’ approval inherent in SOP is more closely related to hope for closeness which is why one acts naturally in a social situation without feeling restricted. Fearing others’ disapproval and rejection, employees high in SPP should act insecure in the same situation. Evidence supports this notion and found SPP to relate to high sensitivity to interpersonal cues that indicate evaluation or rejection (Flett et al., 2014; Hewitt & Flett, 1991).

Research on the perfectionism social disconnection model (Hewitt et al., 2006; Hewitt et al., 2017) also indicates that socially prescribed perfectionists, but not self-oriented perfectionists, experience low social support and feelings of social exclusion, including in the workplace (e.g. Kleszewski & Otto, 2020; Sherry et al., 2008). Supporting the assumption that SOP is related to functional social relationships, previous research indicated that self-oriented perfectionists may have social nurturance goals, show prosocial behaviours, and experience feelings of social connection (Stoeber, 2014; Stoeber et al., 2017).

H3

SOP is positively related (a) and SPP is negatively related (b) to relatedness satisfaction.

To our knowledge, no previous study has examined perfectionism and its association with satisfaction of the three needs in the workplace context. However, this association appears to be reflected in research that linked perfectionism and need satisfaction or frustration in specific contexts. In a clinical sample, perfectionistic concerns led to overall need frustration (Boone et al., 2014). In addition, perfectionistic concerns and perfectionistic strivings showed opposite relationships with overall need frustration and need satisfaction in a sample of junior athletes (Jowett et al., 2016). Finally, for a sample of junior sport participants, a negative association was found between perfectionistic strivings and competence frustration. By contrast, a positive association was found between perfectionistic concerns and the frustration of all three needs (Mallinson-Howard & Hill, 2011). Those findings provide initial support for the hypothesized relationships. However, they are either restricted to especially vulnerable (Boone et al., 2014), high performing samples (Jowett et al., 2016) and domain-specific perfectionism (Mallinson-Howard & Hill, 2011), or focused on overall need satisfaction (Boone et al., 2014; Jowett et al., 2016). We aimed to demonstrate that perfectionism and its consequences also apply to the workplace. We further aimed to investigate the association of perfectionism with the three separate needs because we propose them to show distinct associations with well-being over time.

Basic need satisfaction as an underlying mechanism between perfectionism and well-being

To complete the bridge, why exactly need satisfaction should explain various associations between perfectionism and well-being, we need to consider the consequences of need satisfaction. SDT maintains that need satisfaction contributes to optimal functioning and psychological well-being, whereas need frustration leads to diminished well-being, also in the workplace (Deci et al., 2017). Hence, each of the three needs is proposed to be significant (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Within SDT, well-being is understood as “a subjective experience of affect positivity but […] also an organismic function in which the person detects the presence or absence of vitality” (Deci & Ryan, 2000, p. 243). This understanding fits well our conceptualization of employee well-being encompassing job satisfaction (affect positivity), work engagement (presence of vitality), and exhaustion (absence of vitality).

Specifically, the three needs can be hypothesized to provide employees with the motivational fuel to flourish and dedicate themselves to their work (i.e. engagement; Deci et al., 2001) and experience pleasure (i.e. job satisfaction). Moreover, it can be assumed that a lack of this fuel makes employees vulnerable and depletes their energy resources (i.e. exhaustion; Van den Broeck et al., 2008). In line with these assumptions, the relevance of need satisfaction has been demonstrated for positive indicators of well-being, such as job satisfaction and work engagement, and negative indicators, such as exhaustion (e.g. Van den Broeck et al., 2008, 2010). Whereas the majority of studies employed cross-sectional designs to investigate the association between need satisfaction, some researchers demonstrated that need satisfaction predicted daily well-being (Bakker & Oerlemans, 2016) or well-being over three or 12 months (Huyghebaert et al., 2018; Trépanier et al., 2014). However, these studies were mostly conducted without considering the unique influence of the three needs (see Trépanier et al., 2016, for an exception). Even in cross-sectional studies, the three needs were found to be differently related to well-being, with autonomy satisfaction appearing particularly important for work engagement (Kovjanic et al., 2012; Trépanier et al., 2013; van Tuin et al., 2021). These findings align with the conclusion of a recent review in which autonomy was found to display the highest relative weights on engagement, job satisfaction, and burnout when controlling for its overlap with competence and relatedness. Competence, by contrast, showed no unique contribution to work engagement but relatively high weights on measures primarily characterized by positive affect (Van den Broeck et al., 2016). Longitudinal findings also provide support for investigating the impact of the three separate needs to gain a deeper understanding of which needs predict which indicators of well-being. They further show that need satisfaction does not equally predict well-being over time. For example, overall need satisfaction predicted work engagement but not burnout over a 12-month interval (Trépanier et al., 2014). In a study conducted over a 3-month interval, overall need satisfaction predicted work engagement and job satisfaction (Huyghebaert et al., 2018). Finally, a study that investigated the three needs and their satisfaction or frustration as separate predictors of psychosomatic complaints found significant effects of competence and relatedness satisfaction over a 12-month interval (Trépanier et al., 2016).

Coming back to SDT, it is clearly proposed that “autonomy occupies a unique position in the set of three needs: […] being able to satisfy the need for autonomy is essential […] for many of the optimal outcomes associated with self-determination” (Deci & Ryan, 2000, p. 242). According to Ryan and Deci (2017), the need for autonomy has a special role as a need because it is deeply connected to the integration of individuals’ experiences and thus to the accompanying sense and experiences of coherence and vitality, a feeling of aliveness and energy (Ryan & Frederick, 1997). They describe the need for autonomy as a “vehicle” (p. 97) enabling individuals to bring all their resources, interests and abilities to the action and consider that full satisfaction of the other needs is enhanced only when autonomy is simultaneously satisfied. In line with these assumptions, research has shown that, for example, successful task performance enhanced experiences of vitality only when individuals experienced both competence and autonomy (e.g., Nix et al., 1999). However, no such a differential effect has been found for happiness.

Linking this unique, vitalizing nature of autonomy with Warr’s model of well-being, we attribute a unique “booster” role to autonomy satisfaction in fostering well-being that indicates high activity and energy. The energy aspect of well-being is essential in the definition of work engagement which is characterized by high pleasure as well as high activation (Bakker & Oerlemans, 2011). Thus, we consider work engagement as prototypical for optimal outcomes associated with self-determination. Job satisfaction and exhaustion are indicators of well-being that are characterized by low activation and different affective valences. We propose that competence and relatedness satisfaction may predict these indicators of well-being. Both competence and relatedness satisfaction are proposed to fuel positive experiences in terms of mastery and belongingness which are relevant for high or low pleasure. However, only autonomy satisfaction will simultaneously fuel positive affect and boost activity and thus uniquely predict work engagement in addition to job satisfaction and exhaustion.

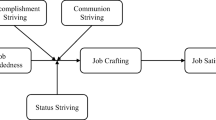

Drawing on the theory and empirical evidence outlined above, we propose need satisfaction as a mediating mechanism between dimensional perfectionism and employee well-being. SDT posits that individuals show optimal functioning and well-being to the extent they experience opportunities to access or construct satisfaction of their needs as the necessary nutriment. Given that SOP facilitates satisfaction of the three needs, this dimension is expected to show positive associations with indicators of well-being. As opposed to this, SPP is assumed to hinder employees from experiencing autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction. Thus, they are expected to have a lack of the fuel that is necessary to engage in work tasks, experience pleasure and that protects them from energy depletion. We propose a unique role to autonomy satisfaction in fostering work engagement and thus expect SOP and SPP to be differently related to all indicators of well-being via autonomy satisfaction only (H4 and H5). We further expect SOP and SPP to be differently related to job satisfaction and exhaustion via competence and relatedness satisfaction (H6–H9). Figure 1 summarizes and illustrates the proposed model.

H4

SOP is positively related to work engagement (a) and job satisfaction (b) and negatively related to exhaustion (c) via autonomy satisfaction.

H5

SPP is negatively related to work engagement (a) and job satisfaction (b) and positively related to exhaustion (c) via a lack of autonomy satisfaction.

H6

SOP is positively related to job satisfaction (a) and negatively related to exhaustion (b) via competence satisfaction.

H7

SPP is negatively related to job satisfaction (a) and positively related to exhaustion (b) via a lack of competence satisfaction.

H8

SOP is positively related to job satisfaction (a) and negatively related to exhaustion (b) via relatedness satisfaction.

H9

SPP is negatively related to job satisfaction (a) and positively related to exhaustion (b) via a lack of relatedness satisfaction.

Method

Procedure

A two-wave online-study was conducted in a sample of full- and part-time employees in Germany. The online-questionnaires were hosted by the non-commercial platform SoSci Survey. Data were collected at two time points, separated by three months. Data collection for Time 1 started in January 2020 and finished in March, before any restrictions concerning the COVID-19 pandemic were implemented. Data collection for Time 2 started in April and finished in June when restrictions such as remote work and home schooling existed. The link to the study was distributed via mailing lists among university staff members and business contacts; it was also advertised via several social media channels. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the department of psychology in Marburg (approval number 2019-61 k). Participation was voluntary. A draw for two wellness vouchers (each worth 50 euro) and five gift cards (each worth 10 euro) was offered as an incentive for participation. All participants provided their informed consent before completing the questionnaires.

Sample

At Time 1, 331 employees completed the questionnaire. Of these, three participants were excluded because their data showed a Mahalanobis distance exceeding the critical value of χ2 (14) = 36.12, p < 0.001 (see Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Hence, the final sample comprised 328 employees. Among them, 230 were female (70%), 97 were male (30%), and 1 was non-binary. Their mean age was 38.21 years (SD = 13.06). The sample was highly educated, with about the half of the participants having a university degree (45%). On average, they worked 34.54 h a week (SD = 13.15) and had an organizational tenure of 8.92 years (SD = 10.25). All branches of the economy were represented, with health and social services (25%), public administration (13%), industry (13%), and education (12%) being the most frequent ones.

Our target sample size was a minimum of 300 employees for T1 and 200 employees for T2, assuming a retention rate between 60 and 70%. To determine the T2 sample size, we used the application by Schoemann et al (2017) that conducts power analyses for multiple mediator models based on Monte Carlo confidence intervals using correlations between the variables as the input method. We based our calculations on previous studies that found moderate correlations between perfectionism and need satisfaction, at least moderate correlations between need satisfaction and well-being over time, and moderate intercorrelations between the three needs (Huyghebaert et al., 2018; Jowett et al., 2016; Trépanier et al., 2016).

The same participants were contacted again via e-mail and 195 of them completed the second questionnaire (59%). An anonymous self-generated identification code was used to match the data from the two waves. A total of 138 data sets was successfully matched and included in the analyses. For the remaining data, there were discrepancies in the codes between T1 and T2. The procedure of self-generated identification codes has many benefits including truly anonymous collection of data and increased appearance of confidentiality, but also the disadvantage of potential data loss if participants do not remember and precisely self-report the code (Audette et al., 2020). This loss leads to an average matching rate of 65% which reflects well the matching rate of 70% in the present study. Thus, the final retention rate was 42% which is not uncommon for two-wave studies in organizational settings (e.g. Huyghebaert et al., 2018). A sample of 138 aligns with recommendations for testing indirect effects based on small to medium path coefficients using bias corrected (BC) bootstrapping (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). As will be described in more detail in Sect. "Statistical analyses", we used BC boostrapping and full information maximum likelihood estimation to provide adequate power for our final sample size and to deal effectively with missing data.

Nevertheless, it can be assumed that some participants have dropped out at Time 2 because their private and working life was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. We analysed whether differences in study and demographic variables could be found between participants who completed both questionnaires and those who only participated at Time 1. The completers were older, t(326) = 2.75, p = 0.006, and had a higher organizational tenure, t(326) = 2.36, p = 0.019, than those who only participated at Time 1. However, there were no significant differences in perfectionism, need satisfaction and the indicators of well-being, indicating that attrition did not occur on the basis of study variables.

Measures

Participants’ demographic information, perfectionism, need satisfaction, and well-being were measured at Time 1 (T1). Well-being was measured again at Time 2 (T2). In addition, the impact of COVID-19 on the participants’ working life and negative life events were assessed at T2. To provide an estimate for the reliability of measures, we used McDonald’s Omega (1999), which is recommended as an alternative that overcomes limitations of Cronbach’s alpha (e.g., Hayes & Courtts, 2020).

Perfectionism

Perfectionism was assessed with a 15-item version of the Dimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS; Hewitt & Flett, 1991; German translation: Altstötter-Gleich, 1998). The short form by Cox et al. (2002) was used to measure SOP (5 items; e.g. “I strive to be as perfect as I can be.”; ω = 0.86) and SPP (5 items, e.g. “People expect nothing less than perfection from me.”; ω = 0.88). Items were presented with a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) and the MPS standard instruction. The shortened scales are a reliable and valid measure of perfectionism (Stoeber, 2018a) and have been used by several researchers (e.g. Stoeber et al., 2020).

Basic psychological need satisfaction

The Work-related Basic Need Satisfaction scale (W-BNS; Van den Broeck et al., 2010; German translation: Martinek, 2012) was used to measure need satisfaction at work. The three subscales comprise autonomy satisfaction (6 items, e.g. “I feel free to do my job the way I think it could best be done.”; ω = 0.84), competence satisfaction (6 items, e.g. “I feel competent at my job.”; ω = 0.87), and relatedness satisfaction (6 items, e.g. “At work, I feel part of a group.”; ω = 0.82). Items were rated on a scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Indicators of employee well-being

Job satisfaction was assessed with the item “Overall, how satisfied are you with your job?” (Wanous et al., 1997) and rated on scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 7 (very satisfied). Single items perform well for capturing overall job satisfaction (Fisher et al., 2016). The exhaustion subscale of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI; Demerouti et al., 2003) was used to measure exhaustion (8 items, e.g. “During my work, I often feel emotionally drained.”; ω = 0.86/0.86 for T1/T2 respectively). Participants rated their responses on a scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). To capture work engagement, the 9-item version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale was used (UWES-9; Schaufeli et al., 2006). The nine items (e.g. “I am immersed in my work”; ω = 0.94/0.95 for T1/T2 respectively) were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always).

Control variables

We controlled need satisfaction and T2 well-being for gender (0 = female, 1 = male), age, and organizational tenure (both in years). Previous research has shown these variables to be related to need satisfaction (e.g. Van den Broeck et al., 2016) and indicators of well-being, such as exhaustion and work engagement (e.g. Purvanova & Muros, 2010; Schaufeli et al., 2006). We also controlled T2 well-being for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the participants’ working life and negative life events. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all areas of life, including changes in work practices and private life, and has been related to reduced well-being (Trougakos et al., 2020). Private demands have been shown to spillover to the work domain and to affect an individual’s exhaustion and work engagement (e.g. Bakker et al., 2005). The impact of the pandemic was assessed with the question “To what extent does the COVID-19 pandemic affect your working life?”, which was rated from 1 (not at all) to 6 (very much). Negative life events (0 = no, 1 = yes) were assessed with the question “Was there an incident within the last 6 weeks that had a negative effect on your well-being (e.g. divorce, serious illness, death of a close person, an accident…)?”.

Statistical analyses

We used path analysis including multiple mediators and outcomes to test all hypotheses simultaneously and applied a half-longitudinal design (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). In theory, perfectionism is conceptualized as a personality disposition. Consistent with this conceptualization, perfectionism has been shown to be relatively stable over months and years (e.g. Sherry et al., 2013). Hence, a natural causal chain can be assumed for the associations of perfectionism and need satisfaction. We thus investigated the contemporaneous relations between perfectionism and need satisfaction and used the time lag to examine the prospective relations between need satisfaction and well-being. For this purpose, we included the autoregressors of T2 well-being indicators at T1 in our path model. Configural and metric measurement invariance are important preconditions to ensure meaningful interpretations of the relation between variables over time (Finkel, 1995; Little et al., 2007). As recommended (Brown, 2006), we followed a step-up approach to test for these types of invariance across time points, before testing the proposed path model.

This model included paths from the perfectionism dimensions (T1) to the three needs (T1) and to the indicators of well-being (T2). It further included paths linking the three needs (T1) and the autoregressors of well-being (T1) to well-being (T2). The control variables gender, age, and tenure were included as predictors of need satisfaction (T1) and well-being (T2), and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and negative life events as additional predictors for well-being (T2). In line with previous research (Laguna et al., 2017), missing data was handled by the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure, which is a modern approach to handling missing data that allows using all available information without imputation and drawing conclusions about the entire sample (Little, 2013; Little et al., 2014). FIML can be considered to be superior to other missing data strategies and estimates unbiased parameters and standard errors if the missing values on the variables are missing at random (Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Raykov, 2005). We inspected missing data using Little’s (1988) Missing Completely at Random Test, which indicated that missingness was random (p > 0.05). Thus, data from participants who responded only at Time 1 could be included. To test the significance of the mediating (i.e. indirect) effects,Footnote 2 we estimated 95% bias corrected confidence bootstrap intervals with 10,000 resamples (MacKinnon et al., 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). In addition, we applied the Benjamini–Hochberg correction (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) with a model-based false discovery rate of 0.05 to reduce the risk of false positives due to multiple testing. The specific paths and indirect effects that achieved conventional significance but were declared nonsignificant by the correction are reported in the text, tables, and figures. Descriptive statistics and correlational analyses were calculated using IBM SPSS Version 27. Both measurement invariance analyses and path analysis were performed using Mplus Version 7.

Results

Correlational analyses

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of the variables are depicted in Table 1. As in previous studies (Flett et al., 2014; Stoeber et al., 2020), SOP and SPP were positively correlated (r = 0.20, p < 0.001). Partial correlations reflected the common differential associations. These included a positive correlation of SOP and job satisfaction (r = 0.13, p < 0.024, at T1) and work engagement (r = 0.25, p < 0.001, at T1 and r = 0.24, p = 0.004. at T2). They also revealed a negative correlation of SPP with job satisfaction (r = − 0.12, p = 0.029, at T1 and r = -0.20, p = 0.021, at T2) and work engagement (r = − 0.20, p = 0.019, at T2), and a positive correlation between SPP and exhaustion (r = 0.32, p < 0.001, at T1 and r = 0.35, p < 0.001, at T2). Moreover, the control variables displayed significant correlations with need satisfaction and well-being. Among these, the smallest correlation was found for gender and exhaustion (r = − 0.13, p = 0.018, at T1) and the largest correlation for age and competence (r = 0.24, p < 0.001).

Measurement invariance

To test for configural and metric invariance, we estimated longitudinal confirmatory factor analyses for all repeated measures. The invariance of factor loadings over time was assessed by comparing a model in which the factor loadings were constrained as equal over measurements with a model, in which factor loadings were unconstrained over time. We allowed the error variances of same items over time to correlate (Little et al., 2007). Conventional criteria (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh et al., 2004) were used to assess a good (χ2/df ratio < 3.00, CFI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, SRMR ≤ 0.10) or an excellent model fit to the data (χ2/df ratio < 2.00, CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, SRMR ≤ 0.08). The results are shown in Table 2. Both configural and metric invariance could be demonstrated for all variables.

Path analysis and hypothesis testing

The path model had an excellent fit to the data (χ2 = 12, df = 12, p = 0.51, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.000, SRMR = 0.021). The model explained a significant proportion of variance for the mediators autonomy (R2 = 0.11), competence (R2 = 0.17), and relatedness satisfaction (R2 = 0.05), and for the T2 outcomes work engagement (R2 = 0.75), job satisfaction (R2 = 0.55), and exhaustion (R2 = 0.72). The indicators of well-being displayed significant stabilities over time (β = 0.69, β = 0.40, β = 0.76, p < 0.001, for work engagement, job satisfaction, and exhaustion, respectively). Concerning a potential common method bias, we used a unmeasured latent factor to assess the common variance among the variables in the path model (Podsakoff et al., 2003). This factor explained only 3% of the variance, which is well below the threshold of 25% (Williams et al., 1989). Thus, common method variance was unlikely to have distorted the participants’ responses.

Standardized path coefficients from the path model are depicted in Fig. 2. The hypothesized specific indirect effects are depicted in Table 3. Hypotheses 1–3 referred to the association of perfectionism (T1) and need satisfaction (T1). All of them reached conventional significance: SOP displayed a significant positive relationship with satisfaction of the three needs (H1a, H2a, and H3a); SPP showed significant negative relationships to satisfaction of the three needs (H1b, H2b, and H3b). After applying the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) correction, the positive associations of SOP with autonomy (BH adjusted p = 0.083) and relatedness satisfaction (BH adjusted p = 0.072) were no longer significant. Thus, Hypotheses 1b, 2a, 2b, and 3b were supported.

Hypotheses 4–9 referred to the indirect effects of perfectionism (T1) with well-being (T2) via need satisfaction (T1). We describe the results concerning these hypotheses structured according to the three needs, beginning with autonomy (H4 and H5) and followed by competence (H6 and H7) and relatedness satisfaction (H8 and H9).

Results from the bootstrapping analyses indicated significant indirect effects of SOP on T2 work engagement (H4a) and T2 job satisfaction (H4b) through autonomy. However, these effects were declared non-significant by the BH correction (BH adjusted p = 0.105 and p = 0.109, repectively). Considering this, Hypotheses 4a and 4b were not supported.

The results provided support for Hypotheses 5a and 5b, showing significant negative indirect effects of SPP on T2 work engagement (H5a) and T2 job satisfaction (H5b) through T1 autonomy satisfaction. Hypotheses 4c and 5c had to be rejected as the indirect effects of SOP (H4c) and SPP (H5c) on T2 exhaustion through T1 autonomy were not significant.

The results showed significant indirect effects of SOP (H6a) and SPP (H7a) on T2 job satisfaction through T1 competence satisfaction. After applying the BH correction, the effects were no longer significant (BH adjusted p = 0.082). Further, the indirect effects of SOP (H6b) and SPP (H7b) on T2 exhaustion through T1 competence satisfaction were not significant. It should be noted that these indirect effects were in the expected direction. Nevertheless, Hypotheses 6 and 7 were not supported.

For both SOP (H8a) and SPP (H9a), the indirect effects on T2 job satisfaction through T1 relatedness satisfaction failed to reach significance which is why Hypotheses 8a and 9a could not be confirmed. Lastly, the results from the bootstrapping analyses showed a significant negative indirect effect of SOP (H8b) as well as a positive indirect effect of SPP (H9b) on T2 exhaustion through T1 relatedness satisfaction. However, the effect of SOP on exhaustion via relatedness satisfaction was declared non-significant by the BH correction (BH adjusted p = 0.070). Thus, the findings only provided support for Hypothesis 9b.

The results remained largely unchanged when the analyses were conducted without the controls and included the three outliers.Footnote 3 The exceptions were the paths from SOP to autonomy (β = 0.09, p = 0.092) and relatedness satisfaction (β = 0.11, p = 0.054), which were not significant without control variables. In addition to the non-significant findings after the BH correction, these findings indicate that these paths should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

Current findings

Grounded in SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2000), this study investigated the mediating role of basic need satisfaction in the different relationships of dimensional perfectionism and employee well-being. Specifically, we considered the distinct associations between the dimensions of perfectionism and satisfaction of the three needs (H1–H3) and proposed distinct associations of the three needs with well-being over time, resulting in specific indirect effects (H4–H9). Several results were consistent with our hypotheses. Some findings, however, raise a need for discussion.

The findings clearly demonstrate that different dimensions of perfectionism have different relationships with the satisfaction of basic needs due to different motivational qualities. It can be concluded that SOP facilitates competence satisfaction and at least does not hinder autonomy and relatedness satisfaction, whereas SPP hinders the satisfaction of the three needs. As predicted, SOP was positively related to competence satisfaction (H2a) and SPP was negatively related to satisfaction of all three needs (H1b, H2b, H3b). These findings are congruent with previous research on perfectionism and need satisfaction in various contexts (e.g. Boone et al., 2014; Jowett et al., 2016; Mallinson-Howard & Hill, 2011). Our findings also showed positive associations of SOP with autonomy and relatedness satisfaction (H1a, H3a) which should be interpreted with caution. These associations were only significant using conventional significance and were not evident when the analyses were conducted without control variables; besides, the effect sizes were small (Cohen, 1992). One explanation for the small effect sizes may be that SOP is more self-determined than SPP but not fully autonomous. Research suggests that SOP not only shows positive associations with intrinsic motivation, the most self-determined regulatory style, but also with identified and integrated regulation (Stoeber, et al., 2018). Further, Thrash and Hurst’s (2008) findings on performance goals suggest that individuals who pursue approach goals may appear to be approach-oriented in their behaviour, but may still be avoidance-oriented in their motivation. Thus, they could have a hidden fear of failure. This may be similar for individuals high in SOP striving towards others’ approval. In terms of affiliation, SOP may entail hope for closeness but also a hidden fear of rejection. This overall ambivalent tendency may hinder individuals high in SOP from experiencing high levels of autonomy and relatedness satisfaction.

Consistent with our expectations, autonomy and relatedness satisfaction mediated the associations of SPP with distinct indicators of well-being: SPP was negatively related to work engagement (H5a) and job satisfaction (H5b) through autonomy satisfaction, and relatedness satisfaction explained the positive association between SPP and exhaustion (H9b). For SOP, there was a certain tendency towards the opposite pattern. SOP was positively related to work engagement (H4a) and job satisfaction (H4b) through autonomy satisfaction, and relatedness satisfaction explained the negative association between SPP and exhaustion (H8b). However, these findings were only significant using conventional significance and should be interpreted with caution. This also applies to the finding that differences in competence satisfaction accounted for the different relationships of SOP and SPP with job satisfaction (H6a and H7a).

It appears that the three needs represent separate mechanisms that explain the associations of perfectionism and well-being. As derived from SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2000) and Warr’s framework (1990, 2013), autonomy satisfaction takes a unique role in fostering activity and explaining why socially-prescribed perfectionists but not self-oriented perfectionists lack engagement at work. Competence and relatedness satisfaction may explain the different associations of perfectionism and indicators of well-being that are characterized by low activation but differ in high or low pleasure.

Contrary to our expectations, competence only showed a tendency to explain the relationship of perfectionism and job satisfaction and relatedness only accounted for the relationship of perfectionism and exhaustion. Further, autonomy satisfaction did not predict exhaustion over time. An explanation for these findings may be that the experiences deriving from the three needs should be considered as relatively distinct concerning the quadrants of Warr’s model. These unique experiences may become especially relevant when the needs are investigated simultaneously. Autonomy satisfaction with its boosting nature may particularly predict positive indicators that indicate the presence of activity and pleasure such as work engagement. A sense of belonging can be described as closely related to the perception of social support available at work which has been found to be a relevant resource for the avoidance of exhaustion (Halbesleben, 2006). Against the backdrop of the current findings, it may be speculated that competence satisfaction and feelings of mastery may be most closely associated with pleasure and thus predict indicators of well-being such as job satisfaction. Nevertheless, the evidence for this association was rather vague in this study. Shifting the focus from well-being to outcomes that represent actual employee behaviour, it could be argued that competence satisfaction is uniquely relevant to variables such as effort and task performance. For these variables, competence satisfaction displayed the highest relative weights in the review by Van den Broeck et al. (2016).

Overall, these findings align with cross-sectional studies (Kovjanic et al., 2012; Trépanier et al., 2013) and the meta-analytic review (Van den Broeck et al., 2016) indicating that autonomy satisfaction is particularly important for well-being. They are also consistent with findings from longitudinal studies which demonstrated that need satisfaction may not equally predict all indicators of well-being over time (Trépanier et al., 2014).

Theoretical implications

This research advances and integrates knowledge about perfectionism and need satisfaction in the workplace. Our results provide evidence that perfectionism can be understood on terms of a dispositional form of motivation. SOP can be seen as representing the more autonomous, approach-oriented, and overall more self-determined form that may enable need satisfaction, especially satisfaction of the need for competence. SPP can be described as the controlled, avoidance-oriented form of this disposition indicating a lack of self-determination and hindering need satisfaction. Thus, our findings emphasize the close interrelation of personality and motivation.

Further, the results demonstrate that the three needs represent separate mechanisms underlying the different associations of perfectionism and well-being. We thus extend previous research that focused on perfectionism and overall need satisfaction (e.g. Jowett et al., 2016) and contribute to a more detailed understanding of how the three needs links dimensional perfectionism to employee well-being. This study provides an answer to the initial question of why the dimensions of perfectionism are differently related to employee well-being, by using SDT and the universal concept of need satisfaction as an explanation. Basic psychological needs represent a crossroad to either optimal or poor functioning (Ryan & Deci, 2000), making this mechanism a starting point for prevention and promotion of well-being among perfectionist employees. This extends previous knowledge concerning mechanisms. Rumination, for example, which is derived from the initiation-termination model of worry (Berenbaum, 2010) explains the association of perfectionistic concerns and poor functioning (e.g. Flaxman et al., 2018). Basic psychological needs, on the contrary, can be considered as mechanisms that also explain why perfectionistic strivings can be related to adaptive, high functioning. Confirming previous findings from clinical and high performing contexts (Boone et al., 2014; Jowett et al., 2016), our results indicate that this mechanism can be applied to various contexts to explain differences in well-being.

From the SDT perspective, our findings further highlight the active role of individuals in contributing to opportunities in which autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction can be experienced. Thus, both contextual factors, such as autonomy support, and individual difference variables should be taken into account as antecedents of need satisfaction within the SDT framework. This idea is also in line with the findings by Baard et al. (2004) which indicated that contextual factors and individual differences were independently related to experiencing need satisfaction.

Additionally, we specify SDT regarding the unique contributions of the needs in predicting well-being over time. Our results highlight the importance of investigating the three needs as distinct constructs as they may be considered to have unique associations with well-being as conceptualized by Warr’s framework. Autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction can be described to align with different quadrants of this model and thus to explain different associations of perfectionism and well-being. According to our results, autonomy satisfaction has a unique role for positive well-being and fosters both active functioning and pleasure (i.e. work engagement and job satisfaction). Competence and Relatedness satisfaction may be more relevant in contributing to well-being that is characterized by low activation and low pleasure. Satisfaction of this need may uniquely prevent employees from exhaustion, probably by signalizing availability of social resources, when all needs and different indicators of well-being are investigated simultaneously. The role of competence satisfaction within Warr’s framework remains open for further investigation, although there may be a certain tendency of this need to foster well-being that is primarily characterized by high pleasure (i.e. job satisfaction).

Strengths, limitations, and future research directions

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate perfectionism and need satisfaction in the workplace and to focus on the three needs as separate mechanisms that explain the differential relationship of dimensional perfectionism and employees’ well-being. By examining the three needs as separate constructs, and by including positive and negative indicators of well-being, we address suggestions from previous research and provide detail about the underlying mechanisms (Ocampo et al., 2020; Van den Broeck et al., 2016; Warr, 2013). Moreover, we investigate these associations using a two-wave design and address recent calls that encouraged to go beyond cross-sectional designs in the area of perfectionism (Stoeber, 2018b) and SDT (Deci et al., 2017; Van den Broeck et al., 2016).

Our findings should be interpreted in the light of certain limitations. To begin with, the present study solely relied on self-reported measures which have several shortcomings, such as a possible common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In this study, common method bias was unlikely to distort the results. Nevertheless, it should be considered that the appropriateness of self-reports depends on the construct that is investigated. Self-reported measures can be considered highly appropriate for assessing constructs such as need satisfaction (Van den Broeck et al., 2016; see also Chan (2009), for a detailed discussion). Overall, subjective and objective indicators of well-being show high correlations (Oswald & Wu, 2010). However, a positive subjective evaluation may also differ from objective indicators of well-being (e.g. Jackowska et al., 2011), and SDT researchers encourage future studies to include objective measures of well-being outcomes (Deci et al., 2017; Van den Broeck et al., 2016). Particularly with regard to work engagement, an employee’s subjective view may differ from their actual behaviour. As suggested by Schaufeli (2012), researchers could use behaviorally anchored rating scales to obtain ratings by supervisors or co-workers in addition to solely relying on self-reports when measuring work engagement.

Second, there are further conceptualizations of perfectionism that capture additional aspects of perfectionistic concerns, such as concern over mistakes and doubt about actions (Frost et al., 1990), or discrepancy (Slaney et al., 2001). Future studies could incorporate and combine different models of perfectionism to cover the full range of the construct. In addition and in line with previous studies (e.g. Dunkley et al., 2014; Flaxman et al., 2018), future research should include conscientiousness and neuroticism as control variables to determine the unique contribution of the perfectionism dimensions beyond broader personality traits. The incremental variance of perfectionism has been demonstrated for work-related outcomes (Clark et al., 2010). However, given the rather small effect sizes in the present study, it would be essential to investigate the robustness of these effects beyond conscientiousness and neuroticism.

Third, the interpretations of the associations of need satisfaction and well-being are limited to a time-lag of 3 months. Researchers have called for more of such “shortitudinal” studies that investigate shorter time lags than the common interval of 1 year than (Dormann & Griffin, 2015). However, they also suggest to integrate short and long time lags to investigate whether findings differ depending on the time frame.

Moreover, future research could consider to include additional measures that may confirm and complement findings from our study. To begin with, the present research did not include a measure for the fourth quadrant in Warr’s model. The construct of workaholism comprises high activation and low pleasure (Bakker & Oerlemans, 2011). SOP has been related to workaholism (Stoeber et al., 2013) which is why it would be interesting to investigate whether autonomy will also uniquely predict this indicator of high activation. In addition, our argumentation that SOP and SPP differ in the extent of autonomy and control causality orientations and approach and avoidance motives could have been tested explicitly, for example, by using the General Causality Orientations Scale (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

Finally, further mechanisms might be important in the association between perfectionism and employee well-being and contribute to the discussion of whether SOP is adaptive or not. Based on the mechanism of stress generation (Hewitt & Flett, 2002), perfectionists might tend to actively create stressors, such as time pressure and working overtime. Perfectionisms cognition theory (Flett et al., 2016) is another promising approach that focuses on cognitive perseveration and that links both SOP and SPP to rumination. In the case of SOP, rumination may be a risk for well-being that opposes the protective function of need satisfaction. Thus, future research should integrate various mechanisms to determine their relative importance and to provide a comprehensive view of possible intervention approaches. In addition, it would be interesting to identify moderator variables that enhance or diminish need satisfaction. SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2000) also attributes a crucial role in need satisfaction to the social context. It could be, for instance, that socially prescribed perfectionists do experience relatedness in a positive team climate; they might also experience autonomy and competence satisfaction when they work under a supportive leader. Transformational leadership has been related to need satisfaction (e.g. Kovjanic et al., 2012) and could be a valuable approach. As opposed to this, socially prescribed perfectionists might experience even less need satisfaction having a perfectionistic leader constantly controlling them and being resentful in the case of mistakes (Otto et al., 2021).

Practical implications and conclusion

Overall, the findings of this study highlight the importance and nourishing function of need satisfaction for employee well-being. Need satisfaction might play a key role in explaining why the different dimensions of perfectionism have different effects on engagement, exhaustion, and satisfaction at work. Especially, enhancing need satisfaction among employees high in SPP might be a promising intervention approach. It can be important to build awareness among such employees regarding their scope of action, successfully completed tasks, and available social support. On an individual level, guided self-help and counselling provide options to support perfectionists (Stoeber & Damian, 2016). At the team and organisational levels, a positive feedback environment could help to establish a sense of personal control (Sparr & Sonnentag, 2008). Team-based interventions focusing on employees’ perspective taking, communication and collaboration have been demonstrated to foster each other's need satisfaction (Jungert et al., 2018). Similar interventions might be promising in teams with employees high in SPP. Nevertheless, harm reduction should not be the only approach. In the long run, overly demanding environments leading to the development of SPP should be questioned, given the wide-ranging consequences of this dimension—including in the workplace. We hope that our findings encourage researchers to further investigate the ways in which perfectionism affects work-related outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Given the externally directed demands, the targets of other-oriented perfectionists tend to experience distress rather than the perfectionists themselves (Hewitt & Flett, 2004). Thus, OOP is usually not included when investigating employee well-being (e.g. Childs & Stoeber, 2012). Rather, researchers separately focus on its impact for significant others via its unique associations with disagreeable behaviour (Stricker et al., 2019). For interested readers, we included OOP in an additional analysis. The results can be found in the supplemental material.

We recognize that some authors (e.g. Mathieu & Taylor, 2006) distinguish between mediation and indirect effects. For the sake of simplicity, the terms are used interchangeably in this work.

In additional analyses, we modelled autoregressive and cross-lagged paths between need satisfaction (T1/T2) and well-being (T1/T2). The significance of the results remained unchanged, which is why we decided to present the more parsimonious model in the manuscript. Results from the cross-lagged model can be found in the supplemental material.

References

Altstötter-Gleich, C. (1998). Deutschsprachige Version der Mehrdimensionalen Perfektionismus Skala von Hewitt and Flett (1991). [German version of the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale of Hewitt and Flett (1991)]. Unpublished manuscript, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany

Audette, L. M., Hammond, M. S., & Rochester, N. K. (2020). Methodological issues with coding participants in anonymous psychological longitudinal studies. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 80(1), 163–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164419843576

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2045–2068. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02690.x

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2005). The crossover of burnout and work engagement among working couples. Human Relations, 58(5), 661–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726705055967

Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2011). Subjective well-being in organizations. In K. S. Cameron & G. M. Spreitzer (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship (pp. 178–189). Oxford University Press.

Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2016). Momentary work happiness as a function of enduring burnout and work engagement. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 150(6), 755–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2016.1182888

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (methodological), 57(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x

Berenbaum, H. (2010). An initiation–termination two-phase model of worrying. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 962–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.011

Besser, A., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2004). Perfectionism, cognition, and affect in response to performance failure vs. success. Journal of Rational - Emotive and Cognitive - Behavior Therapy, 22(4), 301–328. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JORE.0000047313.35872.5c

Bhave, D. P., Halldórsson, F., Kim, E., & Lefter, A. M. (2019). The differential impact of interactions outside the organization on employee well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12232

Boone, L., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., & Verstuyf, J. (2014). Self-critical perfectionism and binge eating symptoms: A longitudinal test of the intervening role of psychological need frustration. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(3), 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036418

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press.

Chan, D. (2009). So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? In R. J. Vandenberg & C. E. Lance (Eds.), Statistical and metholodogical myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity and fable in the organizational and social sciences (pp. 311–338). Routledge.

Childs, J. H., & Stoeber, J. (2010). Self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism in employees: Relationships with burnout and engagement. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 25(4), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2010.518486

Childs, J. H., & Stoeber, J. (2012). Do you want me to be perfect? Two longitudinal studies on socially prescribed perfectionism, stress and burnout in the workplace. Work & Stress, 26(4), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2012.737547

Clark, M. A., Lelchook, A. M., & Taylor, M. L. (2010). Beyond the big five: How narcissism, perfectionism, and dispositional affect relate to workaholism. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(7), 786–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.013

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 558–577. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558

Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Clara, I. P. (2002). The multidimensional structure of perfectionism in clinically distressed and college student samples. Psychological Assessment, 14(3), 365–373. https://doi.org/10.1037//1040-3590.14.3.365

Curran, T., & Hill, A. P. (2019). Perfectionism is increasing over time: A meta-analysis of birth cohort differences from 1989 to 2016. Psychological Bulletin, 145(4), 410–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000138

Danna, K., & Griffin, R. W. (1999). Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management, 25(3), 357–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500305

deCharms, R. (1968). Personal causation: The internal affective determinants of behaviour. Academic Press.

Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientation scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201278002

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Vardakou, I., & Kantas, A. (2003). The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.19.1.12

Dormann, C., & Griffin, M. A. (2015). Optimal time lags in panel studies. Psychological Methods, 20(4), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000041

Dunkley, D. M., Mandel, T., & Ma, D. (2014). Perfectionism, neuroticism, and daily stress reactivity and coping effectiveness 6 months and 3 years later. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(4), 616–633. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000036

Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(3), 430–457. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5

Fairlie, P., & Flett, G. L. (2003). Perfectionism at work: Impacts on burnout, job satisfaction, and depression. Poster Presented at the 111th. Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association at Toronto, Canada

Finkel, S. E. (1995). Causal analysis with panel data. Sage.

Fisher, G. G., Matthews, R. A., & Gibbons, A. M. (2016). Developing and investigating the use of single-item measures in organizational research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039139

Flaxman, P. E., Stride, C. B., Söderberg, M., Lloyd, J., Guenole, N., & Bond, F. W. (2018). Relationships between two dimensions of employee perfectionism, postwork cognitive processing, and work day functioning. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(1), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2017.1391792

Flett, G. L., Besser, A., & Hewitt, P. L. (2014). Perfectionism and interpersonal orientations in depression: An analysis of validation seeking and rejection sensitivity in a community sample of young adults. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 77(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2014.77.1.67