Abstract

Academic achievement is an important developmental goal during adolescence. Two independent factors involved in academic motivation are implicit motives and explicit goals. In this study, we examined whether high school students’ (N = 213) implicit achievement motive, explicit achievement goals, and their interactions were associated with academic goal engagement and disengagement. Our findings showed that academic goal engagement and disengagement were associated with explicit achievement goals only, and not with the implicit achievement motive. However, interactions between the implicit achievement motive and grade aspiration (i.e., a specific explicit achievement goal) revealed that individuals with a low implicit achievement motive can still attain high goal engagement if they have a high grade aspiration. We also found that motive-goal congruence was associated with lower goal disengagement. Overall, these findings suggest that explicit achievement goals and specific academic goals play a dominant role in goal engagement behavior in the structured setting of high schools, and may allow youth to overcome the constraints of having a low implicit achievement motive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Implicit motives, explicit goals, and adolescents’ academic goal engagement

Adolescents’ pursuit of developmental goals sets the stage for their long-term success across domains in life. Adolescents who value educational goals are more likely to experience positive developmental outcomes, as academic achievement during adolescence is associated with long-term success in post-secondary education, career, and even in other life domains (e.g., Roisman et al, 2004). Adolescents most commonly identify education as one of the most important goals they pursue (Chang et al., 2006). As youth generally believe that they have control over educational goals (e.g., You et al., 2011), they often implement strategies to attain them (e.g., Green at el., 2012). One strategy is academic goal engagement, which refers to behavioral and cognitive strategies used to pursue goals and is critical for educational goal attainment (Hall et al., 2006; Hamm et al., 2013). However, levels of goal engagement vary, both within and across individuals in different domains or goals (Heckhausen & Schulz, 1993; Heckhausen et al., 2010). Given its importance for adolescents’ long-term success, it is necessary to identify factors related to higher levels of academic goal engagement. The current study examines two motivational precursors to goal engagement: implicit motives and explicit goals. Both implicit motives and explicit goals have been shown to motivate action (e.g., Kehr, 2004; Schultheiss et al., 2008a, 2008b). However, their respective roles and the interactions between them have not been well-identified in relation to adolescents’ academic pursuit.

Adolescents’ academic goals

Many American high-school students (typically ages 14–18) describe educational goals as their highest priority, have high educational aspirations, and expect to reach these aspirations (e.g., Chang et al., 2006; Yau et al., 2021). Ambitious educational goals are valuable, as they are associated with higher achievement; this is true even in cases in which goals are unrealistic and adolescents do not ultimately attain their initial goals (Heckhausen & Chang, 2009; Villarreal et al., 2015). Adolescents who believe that academics are important earn higher school grades than those who place less value on academics (e.g., Ma, 2001; Miller & Byrnes, 2001). These differences extend longitudinally into post-secondary education, as adolescents with higher academic or career goals while in high school are more likely to complete post-secondary education and have better career trajectories up to ten years later (Vuolo et al., 2014). Thus, it is important to examine factors associated with adolescents’ academic motivation in order to identify strategies to optimize long-term educational and career outcomes.

Implicit motives and explicit goals

Implicit motives and explicit goals are two independent aspects of motivation that are important for academics and other types of goal pursuit (Brunstein, 2018; Brunstein & Maier, 2005; Koestner et al., 1991; McClelland et al., 1989). As studies have reported a low correlation between the two motives (e.g., Thrash & Elliot, 2002), they should be examined separately.

Explicit goals refer to internal representations of desired outcomes that motivate the individual to take action in order to attain the desired outcome (Emmons & Kaiser, 1996; Schultheiss & Brunstein, 1999). These goals are readily accessible cognitively, and they are often formed and prioritized depending on developmental tasks that are most salient during specific life stages (Benson & Furstenberg, 2006). For example, adolescents tend to form goals related to education, as education is particularly salient for development (e.g., Chang et al., 2006; Massey et al., 2008). Explicit goals are strongly associated with short-term goal pursuits in structured settings, and academic goals are highly correlated with educational outcomes (e.g., McClelland et al., 1989, 1992; Rawolle et al., 2013). High achievement goals and desires to achieve academic success can lead to pursuit and persistence in educational goals (Coutinho, 2007; Esparza et al., 2008; Isik et al., 2018), while having low academic aspiration may contribute to adolescents disengaging from educational goals (Abar et al., 2012).

Rawolle et al. (2013) found that general explicit goals (e.g., goals to develop skillsets for job performance) are distinct from specific personal goals (e.g., goals to receive job promotions), suggesting that they should be analyzed separately. The reason is that general explicit goals are more abstract compared to personal goals which are concrete (e.g., Hofer et al., 2010b). The current study will first investigate general explicit achievement goals. Second, academic grade aspiration will be examined for the following reasons: (1) grades are concrete and specific goals in an achievement setting, (2) they are particularly salient as measures of academic performance, and (3) they are a major determining factor for postsecondary education. While the findings from Rawolle et al. (2013) did not specify whether the domain-general explicit goal or domain-specific goal was stronger in predicting outcomes, we expect that grade aspiration will have a stronger association with academic goal engagement and disengagement compared to more general explicit achievement goals because of its specificity and relevance to educational outcomes.

Academic goal engagement can also be driven by implicit motives, which are positive (i.e., rewarding) or negative (i.e., aversive) affective responses that an individual has learned for situations that activate a specific motivational theme (Schultheiss et al., 2010). Implicit motives are formed early in life and are rather stable and unaffected by social influences throughout the lifespan (e.g., McClelland et al., 1989; Schüler et al., 2019a, 2019b). Thus, some researchers have considered implicit motives as trait-like and similar to personality traits (e.g., Apers et al., 2019; Schüler et al., 2019a, 2019b; Woike, 2008). Prior research has identified three main implicit motives, known as The Big Three: (1) Achievement, which refers to individuals' desire to master tasks and reach a standard of excellence (McClelland et al., 1953), (2) Affiliation, which refers to an individuals’ desire to build and maintain relationships (Heyns et al., 1958) and (3) Power, which refers to the desire to influence others (McClelland, 1975). Implicit motives are not directly accessible to conscious thought. Instead, they are assessed through projective assessment via thematic apperception tests such as the Picture Story Exercise (PSE; Pang, 2010). The current study will focus on the achievement motive, which can predict students’ desire to master a challenging task due to genuine interest (Brunstein & Maier, 2005; Koestner et al., 1991) and is beneficial for academic behavior and performance.

Altogether, findings on explicit goals and implicit motives suggest that both of these factors are important and may be associated with adolescents’ academic outcomes (e.g., Brunstein & Maier, 2005; Rawolle et al., 2013). However, the ways in which implicit motives and explicit goals are related to academic motivation have not been sufficiently examined. Depending on the setting, both implicit motives and explicit goals may be important for academic goal pursuits. Implicit motives may play a crucial role because goals that do not reflect implicit motives are more difficult to pursue. Such goals require greater cognitive and behavioral effort to compensate for the lack of affective rewards (Kehr, 2004; Rawolle et al., 2016). This implies that individuals may have greater difficulty in achieving educational goals if they have a low implicit achievement motive. On the other hand, implicit motives are more strongly associated with goal pursuit in unstructured settings and over long periods of time (Kehr, 2004). As adolescents pursue academic goals in a highly structured setting (e.g., exams and assignments with deadlines), it is possible that having a high implicit achievement motive may not be necessary and that compared to other domains of life, explicit goals may be more important for academic success (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018). To our knowledge, no studies have examined the interplay between implicit motives and explicit goals to determine their importance for adolescents’ academic goal engagement. Hence, the current study will shed light on which of these two independent factors may contribute more to adolescents’ educational pursuits.

Motive-goal congruence

While implicit motives and explicit goals are largely independent from one another, individuals can benefit when the two are aligned (e.g., Biernat, 1989; Brunstein & Maier, 2005; Schultheiss et al., 2008a, 2008b). Motive-goal congruence is defined as the alignment of explicit goals and implicit motives, such that both are high or both are low (Thrash et al., 2012). When both are high, goals are expected to be more easily pursued; when both are low, the individual is more likely to disengage from the goal. Given the negative effects of disengaging from academic goals while in high school, the current study will examine congruence of high explicit goals and high implicit motives. Research has shown that motive-goal congruence is beneficial for situations with achievement incentives (e.g., Schüler, 2010), and that achievement goals that are congruent with implicit motives are more successfully attained (e.g., Brunstein & Maier, 2005). Studies have also suggested that pursuing goals that are motive-goal congruent elicits greater effort, persistence, and commitment (e.g., Schultheiss & Brunstein, 1999; Sheldon, 2014). Conversely, when implicit motives and explicit goals are not both high, individuals can suffer from decreases in emotional well-being and have greater difficulty accomplishing their goals (Schüler et al., 2019a, 2019b). The present study will examine the importance of academic motive-goal congruence, namely whether experiencing motive-goal congruence is associated with academic outcomes among youth.

Academic goal engagement and disengagement

Forming goals and having a desire for achievement may lead to greater academic goal engagement, which in turn leads to greater goal attainment (e.g., Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2018; Shane et al., 2012). According to the Optimization in Primary and Secondary Control (OPS) model, individuals use three specific goal engagement strategies when pursuing their goals (e.g., Heckhausen et al., 2010). These strategies are: (1) selective primary control (SPC), (2) compensatory primary control (CPC), and (3) selective secondary control (SSC). Individuals use SPC strategies by investing time and effort in the pursuit of a goal. When the goal becomes challenging and additional strategies are needed, SSC and CPC strategies are also used. SSC refers to increasing the perceived value of a goal (e.g., reminding oneself of the reason for pursuing the goal) and avoiding distractions, while CPC refers to recruiting external support, such as enlisting others’ help or seeking alternative means to pursue the goal.

Altogether, these strategies are necessary for the pursuit of challenging goals (Heckhausen et al., 2010; Heckhausen & Schulz, 1993). During high school, academics become more competitive and challenging (Benner, 2011). This means that it is common for adolescents not only to rely on effort and time investment in their courses (SPC), but that they would also need to avoid distractions (SSC) and to enlist others’ help (CPC) in order to most effectively pursue their academic goals. As these goal engagement strategies are simultaneously used in a high-school setting (e.g., Hamm et al., 2013), they will be combined for analyses.

The OPS model also states that when individuals decide to stop pursuing certain goals, they use compensatory secondary control (CSC) strategies to disengage from that goal (Heckhausen et al., 2010). Disengagement occurs when one uses self-protective strategies after failure, lowers one’s goal aspirations (e.g., adjusting an academic goal downwards from an A to a C in a class), or decides to stop pursuing the goal altogether, with the second and third situations associated with lower goal attainment (Heckhausen et al., 2010; Heckhausen & Schulz, 1993).

Although goal disengagement is beneficial in situations in which the goal truly cannot be attained or when the individual may not have any control over it, disengaging pre-maturely from a goal may have negative consequences. Within the high-school academic context, school is a key developmental task for adolescence because effort placed in academics generally leads to a successful transition to adulthood and is crucial and beneficial for long-term outcomes such as postsecondary educational attainment (Eccles et al., 2004; Galla et al., 2019). High aspirations are associated with greater success, even when goals are not achieved (Villarreal et al, 2015). This suggests that with the rare exception of adolescents who strive to attain careers in which secondary education is not needed, disengagement from academics is maladaptive and should be avoided in this life-stage. Yet, it is common for adolescents to disengage from educational pursuits before they have invested their greatest effort and have used all of the motivational control strategies (e.g., SSC and CPC) to attempt to attain their goal (Doll et al., 2013). To promote goal engagement and prevent goal disengagement from academic goals, it is important to identify factors that can facilitate or hinder these behaviors. Prior studies have demonstrated the benefits of motive-goal congruence with high explicit goals and the implicit achievement motive for outcomes such as well-being and life satisfaction (Hofer & Chastiotis, 2003; Job & Brandstätter, 2009), and others have discussed the positive effects of motive-goal congruence on volitional strength (Thrash et al., 2012). The current study will extend the findings by further examining the positive effects of having motive-goal congruence in an academic setting for adolescents. We predict that motive-goal congruence will be positively associated with goal engagement, and negatively associated with goal disengagement.

Although research on goal engagement and goal disengagement strategies has not focused on demographic differences, prior findings regarding academic motivation and goal pursuit suggest a likelihood that ethnic and socioeconomic (SES) inequities exist (e.g., Browman et al., 2017; Burton, 2007; Isik et al., 2018; Manganelli et al., 2021; Yau et al., 2021). For example, Manganelli et al. (2021) found that adolescents who have a low SES have lower academic motivation and higher levels of amotivation than high-SES adolescents. Adolescents may struggle to stay motivated in school if they do not believe that academic success can lead to social mobility (Browman et al., 2017). Prior research has also shown an association between ethnic differences and academic motivation, as Isik et al. (2018) conducted a meta-analysis and found that there are many factors that are linked to ethnic minority students’ struggle with academic motivation, including the experience of discrimination and lack of social support. Given that ethnic and SES differences may be associated with goal engagement and disengagement, they will be included as covariates in the current study.

The current research

While studies have demonstrated the importance of implicit motives and explicit goals in different domains, no studies have examined the role that motive-goal congruence plays in adolescents’ educational pursuits. The current study examines associations between adolescents’ implicit achievement motive, explicit achievement goals, grade aspiration, academic goal engagement, and academic goal disengagement. First, we examine whether the implicit achievement motive and explicit achievement goals are associated with the use of academic goal engagement and disengagement strategies. Based on prior research showing the importance of implicit motives (Brunstein & Maier, 2005; Koestner et al., 1991), we expect that individuals who have a high implicit achievement motive will have higher academic goal engagement (Hypothesis 1A) and lower academic goal disengagement (Hypothesis 1B). As prior research has also shown the benefits of having high explicit achievement goals in academics (McClelland et al., 1989; Rawolle et al., 2013), we predict that individuals with high explicit achievement goals will have higher academic goal engagement (Hypothesis 2A) and lower academic goal disengagement (Hypothesis 2B). We also expect that grade aspiration will positively predict goal engagement, and this association will be stronger than the association between explicit achievement goals and goal engagement due to its relevance to the educational domain. (Hypothesis 2C). Additionally, we predict that grade aspiration will be negatively associated with goal disengagement and that this association will be stronger than the association between explicit achievement goals and goal disengagement (Hypothesis 2D). Finally, we aim to identify the combined effects of implicit motives and explicit achievement goals on academic goal engagement and disengagement. Based on previous research showing the benefits of motive-goal congruence in an achievement context (Brunstein & Maier, 2005; Schüler, 2010), we expect that the benefit of having high explicit achievement goals on academic goal engagement will be higher when the implicit achievement motive is also high (Hypothesis 3A), and that having high explicit achievement goals will prevent academic goal disengagement more when the implicit achievement motive is high as well (Hypothesis 3B). We also hypothesize that motive-goal congruence (i.e., showing high levels of the implicit achievement motive and grade aspiration) will lead to a higher level of academic goal engagement (Hypothesis 3C) and a lower level of goal disengagement (3D).

Method

Participants and Procedures

High-school students (N = 244) were recruited from four different high-school afterschool programs, and one in-school program in an urban school district in Southern California. A total of 153 participants were recruited from after-school programs, and 91 participants (37.3%) were recruited from an in-school elective college-readiness class aimed at developing students’ writing, reading, critical thinking, and organizational skills. A total of 213 participants were retained in the analyses after excluding those with missing responses from the variables of interest. Missing data analysis showed that the majority of missing data occurred from missing values in parental education (78%). Post hoc power analyses showed that our sample had sufficient power (1 − β > 0.99), and that statistical significance could be detected with a medium effect size (f2 = 0.20). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

All research activities were conducted at the recruitment sites at one time point. After-school site permission was obtained from school or program administrators. Potential participants were informed of the research study and given either a physical copy of the study information sheet to take home to their parents or were sent an email regarding the details of the study. All participants signed an informed consent or assent form (if under 18) before completing a questionnaire that took approximately 45 min. Participants completed the questionnaire on computers in the school library, computer lab, or on paper. Participants received a $10 gift card upon completion. All procedures were approved by the researchers’ Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Questionnaires included measures of implicit motives, explicit achievement goals, grade aspiration, academic goal engagement, goal disengagement, and demographic information.

Implicit motives

Implicit achievement motives were assessed using the PSE (McClelland et al., 1989). Following the recommendations by McClelland, participants were shown six ambiguous pictures with at least two people engaged in an activity. The six picture cues that were included were the following: (1) women in laboratory, (2) couple by the river, (3) bicycle race, (4) teacher and student, (5) couple sitting opposite a woman, and (6) nightclub scene. Participants were asked to spend up to five minutes writing about what they thought was happening while looking at each of the picture cues, and they were allowed to view the picture cue for the entire time that they spent writing the story. A researcher observed their participation to make sure that they spent at least one minute writing each story, and that they were not spending more than five minutes in order to ensure that participants could complete the entire survey in the allotted time.

The implicit achievement, affiliation, and power motive were coded using stories written from the picture story exercise. The PSE has been validated and is the most commonly used method to measure implicit motives (e.g., Schüler et al., 2014, 2015; Schultheiss et al., 2008a, 2008b). Coders were trained using the Winter manual (1994), and a combination of two out of five coders coded each of the stories. Each coder displayed good reliability with another coder when coding sample stories from the Winter manual. Interclass correlations between each pair of coders was acceptable (> 0.70). When there were disagreements between the two coders of each story, the mean scores were used. While all three implicit motives (achievement, affiliation, and power) were coded, only the achievement motive was analyzed and reported for this study. The achievement motive score was created by summing the number of times that the achievement motive was coded across the six stories.

Explicit goals

To measure general explicit achievement goals, the achievement subscale items from the GOALS scale (Pohlmann & Brunstein, 1997) was used. This scale is well-established and has been used in other studies that examine motive-goal congruence (e.g., Hofer & Chasiotis, 2003). The achievement subscale includes four items that asked how important the achievement goals are on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Very.” The achievement goals include “develop my abilities,” “improve my education continuously,” “learn more things,” and “always improve.” These four items were averaged into a composite score and showed good reliability (α = 0.83).

Grade aspiration

Participants’ grade aspiration, a domain-specific and personal explicit achievement goal, was measured with a single item that asked about the grades they aimed to attain on a 6-point scale ranging from “Mostly lower than C’s” to “Mostly A’s.”

Academic goal engagement

Participants’ selective and compensatory primary and secondary control strategies were measured with adapted versions of the optimization in primary and secondary control strategies scales (Heckhausen et al., 1998). Education-related SPC use was measured using four items, such as “I will put time and effort into my education whenever I can.” Participants’ education-related SSC use was also measured with four items, such as “I often remind myself how important it is for my future to have a good education.” Education-related CPC strategy use was measured with three items, such as “If I run into obstacles with my plans, I will ask others for advice.” As all three goal engagement strategies were highly correlated among one another with correlations ranging from 0.55 to 0.65, all items were averaged into a composite scale with a good reliability score (α = 0.84). Items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree’ to “Strongly Agree.”

Academic goal disengagement

Participants’ academic goal disengagement was measured using four items in the OPS scale. All of these items pertained to letting go of the educational goal and not to self-protection. Examples include, “If I cannot attain my educational goals, I will let go of them” and “If I cannot reach my desired educational goals, I will settle for the next best option.” A 5-point Likert scale was used for all of these items, which ranged from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.” The four items were averaged into a composite score, which showed adequate reliability (α = 0.61) and have been used in various studies (e.g., Heckhausen & Tomasik, 2002; Heckhausen et al., 1998).

Demographics

Participants’ ethnicity (White, Latinx, Other), and categorical variables for the highest level of parents’ education (less than high school to university graduates) were gathered and used as covariates in all regression analyses.

Analysis plan

All analyses were conducted in Stata 13 (StataCorp, 2013). First, the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlation method was used to determine discriminant validity between explicit goals and goal engagement, and between explicit goals and goal disengagement (Henseler et al., 2015). Four hierarchical regression models were then used to test all hypotheses. A residualized variable was created for the implicit achievement motive and was used for all regression models because of the high correlation between word count and the achievement motive scores (r = 0.32, p < 0.001), with word count significantly predicting the total achievement motive score (Schönbrodt et al., 2021). The first hierarchical regression model was used to test hypotheses 1A, 2A, and 3A with the implicit achievement motive and explicit achievement goals as predictors and academic goal engagement as the outcome variable. An interaction term between the implicit achievement motive and explicit achievement goals was created and standardized to test in this model. The second hierarchical regression model was used to test hypotheses 1B, 2B, and 3B with the same predictors but with academic goal disengagement as the outcome variable. Interaction terms between the implicit achievement motive and explicit achievement goals were created and standardized for this model as well. The third hierarchical regression model was used to test hypotheses 2C and 3C with the implicit achievement motive and grade aspiration as the predictors and academic goal engagement as the outcome variable. An interaction term between the implicit achievement motive and grade aspiration for goal engagement was created and standardized to assess in this model. Finally, the fourth hierarchical regression model was used to test hypothesis 2D with grade aspiration and the implicit achievement motive as the predictors and goal disengagement as the outcome variable, and hypothesis 3D to assess the interaction between the implicit achievement motive and grade aspiration for goal disengagement. As hypotheses 2C and 2D also stated that the association between grade aspiration and goal engagement and disengagement would be stronger compared to explicit achievement goals, an F-test was conducted to compare the standardized beta coefficients of explicit achievement goals and grade aspiration. Parental education and ethnicity were included as control variables for all models. All models were also tested without controlling for covariates, and no differences were found in the results.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Demographic information, overall means, and standard deviations between key study variables are presented in Table 1. Bivariate correlations for the variables of interest are presented in Table 2. We found an association between the implicit achievement motive and goal engagement (r = 0.13, p = 0.041), but not between the implicit achievement motive and goal disengagement (r = 0.09, p = 0.526). Hence, we do not expect that the implicit achievement motive would negatively predict goal disengagement, which would not support hypothesis 1B. Explicit achievement goals and goal engagement were also associated (r = 0.42, p < 0.001), as were achievement goals and goal disengagement, negatively (r = − 0.21, p = 0.001). Finally, grade aspiration and goal engagement were associated (r = 0.44, p < 0.001), as were grade aspiration and goal disengagement, negatively (r = − 0.23, p < 0.001).

Assessing discriminant validity

As the correlation between explicit achievement goals and academic goal engagement (r = 0.42, p < 0.001), and between explicit achievement goals and goal disengagement (r = − 0.21, p = 0.001) were moderate to high, we first needed to determine whether there was discriminant validity between these variables. Researchers have recommended the use of the hetero-trait monotrait ratio of correlation (HTMT) method due to its high specificity and sensitivity rates (Hamid et al., 2017; Henseler et al., 2015; Rönkkö & Cho, 2020). The HTMT compares the correlation of indicators across different constructs to the correlation of indicators within the same ones. We calculated the HTMT score between explicit achievement goals and goal engagement, and between explicit achievement goals and goal disengagement. The HTMT score between explicit achievement goals and goal engagement was 0.43, and the score between explicit achievement goals and goal disengagement was − 0.21. A score close to 1 shows that the constructs lack discriminant validity, with researchers recommending the use of 0.85 or 0.90 as thresholds for the cutoff (e.g., Hamid et al., 2017; Henseler et al., 2015). The HTMT scores were well below these cutoff scores, indicating that discriminant validity has been established.

Hierarchical regression analyses

In the first model, ethnicity and parental education were entered into the first block as covariates with goal engagement as the dependent variable. The implicit achievement motive and explicit achievement goals were entered into the second block. Results showed a significant improvement in the model, accounting for 22% of the variance in goal engagement [(R2 = 0.22, ΔR2 = 0.17; F(5, 207) = 12.28; p < 0.001)]. We found that the implicit achievement motive did not significantly predict goal engagement (β = 0.08, p = 0.132), which did not support hypothesis 1A. On the other hand, explicit achievement goals were positively associated with goal engagement (β = 0.40, p < 0.001) which supported hypothesis 2A. Results also showed a negative association between the “Others” group for ethnicity and goal engagement compared to Latinx participants (β = − 0.15, p = 0.028). An interaction term with the explicit achievement goals as the predictor and the implicit achievement motive as the moderator was then created and entered into the third block. However, this did not result in a significant change in the model [(R2 = 0.22, ΔR2 = 0.00; F(5, 207) = 11.14; p < 0.001)]. Hypothesis 3A predicted that the congruence of having high explicit achievement goals and a high implicit achievement motive will be positively associated with academic goal engagement, but results for the interaction were not significant (β = − 0.03, p = 0.396). Thus, hypothesis 3A was not supported. Results for the first regression model are presented on Table 3.

In the second hierarchical regression model, parental education and ethnicity were entered into the first block while the implicit achievement motive and explicit achievement goals were entered into the second block. Academic goal disengagement was the dependent variable. The model showed significant improvement after the second block was entered, accounting for 8% of the variance in goal disengagement [(R2 = 0.08, ΔR2 = 0.04; F(6, 206) = 4.84; p < 0.001)]. Results showed that the implicit achievement motive was not associated with goal disengagement (β = 0.05, p = 0.480), which did not support hypothesis 1B. Results also showed that explicit achievement goals were negatively associated with goal disengagement (β = − 0.21, p < 0.001), which confirms hypothesis 2B. Parental education also positively predicted goal disengagement (β = 0.15, p = 0.047). For the third block, the same interaction term was entered with explicit achievement goals as the predictor and the implicit achievement motive as the moderator. The model did not improve significantly after the third block was entered [(R2 = 0.08, ΔR2 = 0.00; F(6, 206) = 4.04; p < 0.001)], and the interaction did not significantly predict goal disengagement (β = 0.02, p = 0.767). Thus, hypothesis 3B was not supported. Results are presented on Table 4.

For the third hierarchical regression model, parental education and ethnicity were entered into the first block with academic goal engagement as the dependent variable. The implicit achievement motive and grade aspiration were entered into the second block, and results showed a significant improvement in the model [(R2 = 0.25, ΔR2 = 0.20; F(6, 206) = 8.31; p < 0.001)]. For the third block, an interaction term was created with grade aspiration as the predictor and the implicit achievement motive as the moderator. Unlike the first two hierarchical regression models, the final model including all three blocks significantly improved the model by accounting for 28% of the variance in goal engagement [(R2 = 0.28, ΔR2 = 0.03; F(6, 206) = 8.37; p < 0.001)]. Results showed a positive association between grade aspiration and goal engagement (β = 0.40, p < 0.001). However when comparing the standardized coefficients for grade aspiration and explicit achievement goals, we found that the difference between the coefficients was not statistically significant in predicting academic goal engagement [F(1, 204) = 0.03, p = 0.862]. Thus, hypothesis 2C was partially supported. Results also showed a positive association between the implicit achievement motive and goal engagement (β = 0.13, p = 0.044), a negative association between parental education and goal engagement (β = = 0.12, p = 0.012), and a negative association between the “Others” ethnic group and goal engagement compared to Latinx participants (β = .− 0.19, p = 0.028).

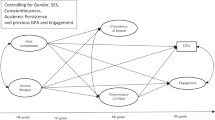

Regarding the interaction term, hypothesis 3C predicted a motive-goal congruence effect between grade aspiration and the implicit achievement motive on goal engagement. As results for the interaction were significant (β = − 0.08, p = 0.035), simple slopes were then tested and plotted at one standard deviation above the mean (+ 1 SD) and one standard deviation below the mean (− 1 SD) of the moderator; the interaction terms were standardized. Results showed that the regression coefficient between grade aspiration and goal engagement was the highest in the condition where the implicit achievement motive was low (− 1 SD) (β = 0.37, p < 0.001) and lowest where the implicit achievement motive was high (+ 1 SD) (β = 0.13, p = 0.033). Thus, a compensatory role of the grade aspiration for the lack of implicit achievement motive was observed instead of the motive-goal congruence effect predicted in hypothesis 3C. Results are presented in Fig. 1 and in Table 5.

For the fourth hierarchical regression model, parental education and ethnicity were entered as the first block with goal disengagement as the dependent variable. The implicit achievement motive and grade aspiration were entered into the second block, with results showing a significant improvement in the model [(R2 = 0.11, ΔR2 = 0.06; F(5, 207) = 5.62; p < 0.001)]. An interaction term between grade aspiration (predictor) and the implicit achievement motive (moderator) was created and entered into the third block. Results showed a significant improvement after the third block was included in the model [(R2 = 0.14, ΔR2 = 0.03; F(6, 206) = 9.12; p < 0.001)], with the final model accounting for 14% of the variance in goal disengagement. There was a negative association between grade aspiration and goal engagement (β = − 0.30, p < 0.001), but we did not find a statistically significant difference between the standardized coefficients for grade aspiration and explicit achievement goals in predicting academic goal disengagement [F(1, 204) = 0.26, p = 0.614]. Hence, hypothesis 2D was partially supported.

Hypothesis 3D predicted a motive-goal congruence effect of having a high grade aspiration and high implicit achievement motive on academic goal disengagement. The interaction term was used to test the prediction, and results showed a significant interaction between grade aspiration and the implicit achievement motive (β = − 0.19, p < 0.001). Simple slopes were calculated with one standard deviation above (+ 1 SD) and one standard deviation below the mean (− 1 SD) of the moderator. Results showed that the regression coefficient between grade aspiration and academic goal disengagement was significant (β = − 0.42, p < 0.001) when the implicit achievement motive was high (+ 1 SD). On the other hand, when the implicit achievement motive was low (− 1 SD), the association between grade aspiration and goal disengagement was not significant (β = − 0.09, p = 0.284). Thus, the results for academic goal disengagement confirmed hypothesis 3D, showing that the benefits of having a higher level of grade aspiration was more pronounced when the implicit achievement motive was high as well. Results are presented in Fig. 2 and in Table 6.

Discussion

The current study examined the association between high school students’ implicit achievement motive, explicit achievement goals, grade aspiration, and education-related goal engagement and disengagement. Unexpectedly, only explicit achievement goals and grade aspiration were associated with academic goal engagement (positively) and academic goal disengagement (negatively). Results showed a compensatory effect, such that individuals with low levels of the implicit achievement motive still had a high academic goal engagement if they had a high grade aspiration. However, our findings indicate that the implicit achievement motive still plays a role in academic pursuits for goal disengagement. Students who had motive-goal congruence (i.e., high implicit achievement motive and high grade aspiration) were least likely to disengage from their academic goals.

The importance of explicit achievement goals and grade aspiration for academic goal engagement

Our results showed that explicit achievement goals and grade aspiration were positively associated with academic goal engagement. The positive main effect of explicit achievement goals on academic goal engagement indicates explicit goals’ prominent role in motivating adolescents to make effort, to invest time, and to persist through challenges as they strive to succeed in school. In other words, our findings suggest that high-school students who have higher explicit achievement goals are more engaged in their education. This supports previous research showing that individuals are more engaged in tasks when they have more ambitious goals (e.g., Villarreal et al., 2015). Furthermore, our findings associated with grade aspiration show that high school students have a strong academic goal engagement if they have a high grade aspiration. On the other hand, the implicit achievement motive did not have a main effect on either academic goal engagement or academic goal disengagement, even though findings from prior studies have indicated the importance of the implicit achievement motive in education-related goal pursuits (e.g., Brunstein & Maier, 2005).

Prior studies have shown that in highly structured settings, having a high level of explicit achievement goals leads to more effort than having a high level of the implicit achievement motive (McClelland et al., 1989, 1992; Rawolle et al., 2013). In line with these previous findings, our study suggests that the highly structured setting of high school creates a situation in which explicit achievement goals and grade aspiration become decisive factors for high academic engagement, whereas the implicit achievement motive is less influential. We also expected an interaction between explicit achievement goals and the implicit achievement motive, but an interaction was found between grade aspiration and the implicit achievement motive only. While this result may have been explained by the specificity of grade aspiration in a school setting, our findings showed that the coefficients for grade aspiration and explicit achievement goals were not significantly different when predicting academic goal engagement and disengagement. Thus, the interpretability of finding an interaction between grade aspiration and the implicit achievement motive only is limited and future studies should further examine why this may be the case.

Motive-goal compensation in academic engagement

Our results suggest the role that grade aspiration plays for academic goal engagement differs depending on the level of the implicit achievement motive. For students with a low implicit achievement motive, having a high grade aspiration was associated with a high goal engagement. This indicates that having a high grade aspiration may compensate for a weak implicit achievement motive and reduce the likelihood of having low academic engagement. Adolescents who aim to achieve high grades may benefit from the structured high-school setting, which guides them and facilitates their academic goal engagement (McClelland et al., 1989, 1992). In this case, having a strong implicit achievement motive may not be necessary. In contrast, grade aspiration for students with a high implicit achievement motive does not make a difference for their academic goal engagement.

Motive-goal congruence in academic disengagement

Although we did not find that having a combination of a high implicit motive and high grade aspiration is associated with higher academic goal engagement, results show that motive-goal congruence is beneficial in reducing academic goal disengagement. Our findings suggest that having high levels of both the implicit motive achievement motive and grade aspiration can keep individuals from disengaging from their academic pursuits. This finding is crucial in regards with prior research which has shown that high-school students are prone to disengage prematurely from their academic goals (e.g., Doll et al., 2013). To help adolescents avoid giving up on their studies when they still have the potential to achieve academic success, educators should help students who have a high implicit achievement motive by encouraging them to aim higher in achieving good grades. This strategy would benefit individuals who have a high implicit achievement motive more compared to those who have a low implicit achievement motive (See Fig. 2). Consistent with prior studies that have demonstrated the benefits of having higher educational aspirations (e.g., Villarreal et al., 2015), our findings suggest that the strategy of helping students to aim for higher academic performance can ultimately help adolescents stay on track with their academic studies.

Demographic influences in academic engagement and disengagement

Parental education was negatively associated with academic goal engagement, and positively associated with goal disengagement. Compared to Latinx participants, the “Other” group had lower goal engagement. These findings are surprising because prior studies have found that students who have lower SES are less academically motivated due to the lack of resources and beliefs that their academic efforts will lead to social mobility (e.g., Browman et al., 2017; Drotos & Cilesiz, 2016; Manganelli et al., 2021). Our finding can be explained by high-SES students’ access to strong external resources which may contribute to their reliance on parents and educators to achieve academic success, thus feeling that it is not as necessary to stay academically self-motivated. Though our findings also indicate ethnic differences in adolescents’ academic goal engagement, future studies should examine this phenomenon using a more diverse and proportionate sample size. Factors that have been identified in the literature such as social support (Isik et al., 2018) could be assessed as potential moderators of the relation between ethnicity and goal engagement.

Limitations

Though this research has valuable implications for theory and practice, there are still several limitations that must be acknowledged. Perhaps most significant is the cross-sectional nature of the data, which does not allow for conclusions about directionality. Longitudinal research is necessary to identify the direction of the associations found in these results. A second limitation is that participants in this study were recruited from elective after-school or in-school activities, some of which were at least partly academic-focused. Because of this, participants may have been more motivated than typical high-school students and had higher academic goals and achievement than the average; these results may reflect associations only among higher-achieving and more motivated students. It would be valuable to ask these same research questions among students who are less motivated or lower-achieving. Third, a one-item measure was used for grade aspiration and future studies could use multi-item scales to assess the grades that students aim to receive in the classroom. Fourth, the reliability score for academic goal disengagement was low. As prior studies have established validity with this measure, it is possible that a bigger sample size may lead to a higher reliability score. Finally, this research included only the participants’ self-reports of their goals and goal-striving behaviors. Although participants’ perspectives are valuable, it is important to extend this research by including external reports from others such as parents or teachers, as well as objective measures of achievement. Obtaining reports from others may lead to more reliable measures of adolescents’ motivation and achievement.

Future research and conclusion

This research supports the importance of the roles that the implicit achievement motive, explicit achievement goals, and grade aspiration play in students’ academic goal engagement and disengagement. We examined the relation between these factors, and our results highlight the importance of the environment-motive fit for goal pursuits. Explicit achievement goals can contribute to academic goal engagement in highly structured settings and prevent disengagement from academic goals. Having an ambitious grade aspiration can compensate for individuals who do not have a strong implicit achievement motive and may lead to goal engagement. For avoiding disengagement from academic goals, congruence between implicit motives and an ambitious grade aspiration is beneficial. Future research can further examine this phenomenon by differentiating between individuals who are avoidance-motived in their implicit achievement motive and those who are approach-motivated (Pang et al, 2009). This can be done by including a measure for having hope for success versus a fear of failure in the implicit achievement motive. In addition, researchers can examine whether the findings replicate with college and graduate students, as the school-setting in universities are much less structured compared to secondary school. Overall, this research helps us to understand factors related to adolescents’ academic motivation and to identify ways to improve adolescents’ academic motivation and pursue educational goals that are important in this life-stage.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Abar, B., Abar, C. C., Lippold, M., Powers, C. J., & Manning, A. E. (2012). Associations between reasons to attend and late high school dropout. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(6), 856–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.05.009

Apers, C., Lang, J. W., & Derous, E. (2019). Who earns more? Explicit traits, implicit motives and income growth trajectories. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 214–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.12.004

Benner, A. D. (2011). The transition to high school: Current knowledge, future directions. Educational Psychology Review, 23(3), 299–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9152-0

Benson, J. E., & Furstenberg F. F. Jr., (2006). Entry into adulthood: Are adult role transitions meaningful markers of adult identity? Advances in Life Course Research, 11, 199–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-2608(06)11008-4

Biernat, M. (1989). Motives and values to achieve: Different constructs with different effects. Journal of Personality, 57(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00761.x

Browman, A. S., Destin, M., Carswell, K. L., & Svoboda, R. C. (2017). Perceptions of socioeconomic mobility influence academic persistence among low socioeconomic status students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 72, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.03.006

Brunstein, J. C. (2018). Implicit and explicit motives. In J. Heckhausen & H. Heckhausen (Eds.), Motivation and action (3rd ed., pp. 369–405). Springer.

Brunstein, J. C., & Maier, G. W. (2005). Implicit and self-attributed motives to achieve: Two separate but interacting needs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(2), 205–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.2.205

Burton, L. (2007). Childhood adultification in economically disadvantaged families: A conceptual model. Family Relations, 56(4), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00463.x

Chang, E. S., Chen, C., Greenberger, E., Dooley, D., & Heckhausen, J. (2006). What do they want in life?: The life goals of a multi-ethnic, multi-generational sample of high school seniors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(3), 302–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9034-9

Coutinho, S. A. (2007). The relationship between goals, metacognition, and academic success. Educate, 7(1), 39–47.

Doll, J. J., Eslami, Z., & Walters, L. (2013). Understanding why students drop out of high school, according to their own reports: Are they pushed or pulled, or do they fall out? A comparative analysis of seven nationally representative studies. SAGE Open, 3(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013503834

Drotos, S. M., & Cilesiz, S. (2016). Shoes, dues, and other barriers to college attainment: Perspectives of students attending high-poverty, urban high schools. Education and Urban Society, 48(3), 221–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124514533793

Eccles, J. S., Vida, M. N., & Barber, B. (2004). The relation of early adolescents’ college plans and both academic ability and task-value beliefs to subsequent college enrollment. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 24(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431603260919

Emmons, R. A., & Kaiser, H. (1996). Goal orientation and emotional well-being: Linking goals and affect through the self. In A. Tesser & L. Martin (Eds.), Striving and feeling: Interactions among goals, affect, and self-regulation (pp. 79–98). Plenum Press.

Esparza, P., & Sanchez, B. (2008). The role of attitudinal familism in academic outcomes: A study of urban, Latino high school seniors. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.193

Galla, B. M., Shulman, E. P., Plummer, B. D., Gardner, M., Hutt, S. J., Goyer, J. P., & Duckworth, A. L. (2019). Why high school grades are better predictors of on-time college graduation than are admissions test scores: The roles of self-regulation and cognitive ability. American Educational Research Journal, 56(6), 2077–2115. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831219843292

Green, J., Liem, G. A. D., Martin, A. J., Colmar, S., Marsh, H. W., & McInerney, D. (2012). Academic motivation, self-concept, engagement, and performance in high school: Key processes from a longitudinal perspective. Journal of Adolescence, 35(5), 1111–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.016

Hall, N. C., Chipperfield, J. G., Perry, R. P., Ruthig, J. C., & Goetz, T. (2006). Primary and secondary control in academic development: Gender-specific implications for stress and health in college students. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 19(2), 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800600581168

Hamid, M. R., Sami, W., & Sidek, M. M. (2017). Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. Journal of Physics Conference Series, 890(1), 012163.

Hamm, J. M., Stewart, T. L., Perry, R. P., Clifton, R. A., Chipperfield, J. G., & Heckhausen, J. (2013). Sustaining primary control striving for achievement goals during challenging developmental transitions: The role of secondary control strategies. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(3), 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2013.785404

Heckhausen, J., & Chang, E. S. (2009). Can ambition help overcome social inequality in the transition to adulthood? Individual agency and societal opportunities in Germany and the United States. Research in Human Development, 6(4), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427600903281244

Heckhausen, J., & Heckhausen, H. (2018). Development of motivation. In J. Heckhausen & H. Heckhausen (Eds.), Motivation and action (3rd ed., pp. 679–743). Springer.

Heckhausen, J., & Schulz, R. (1993). Optimisation by selection and compensation: Balancing primary and secondary control in life span development. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 16(2), 287–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/016502549301600210

Heckhausen, J., Schulz, R., & Wrosch, C. (1998). Developmental regulation in adulthood: Optimization in Primary and Secondary Control—A multiscale questionnaire (OPS-Scales). Max Planck Institute for Human Development.

Heckhausen, J., & Tomasik, M. J. (2002). Get an apprenticeship before school is out: How German adolescents adjust vocational aspirations when getting close to a developmental deadline. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1864

Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., & Schulz, R. (2010). A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychological Review, 117(1), 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017668

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Heyns, R. W., Veroff, J., & Atkinson, J. W. (1958). A scoring manual for the affiliation motive. In J. W. Atkinson (Ed.), Motives in fantasy, action, and society (pp. 205–218). Van Nostrand.

Hofer, J., Busch, H., Bond, M. H., Li, M., & Law, R. (2010b). Is motive-goal congruence in the power domain beneficial for individual well-being? An investigation in a German and two Chinese samples. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 610–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.08.001

Hofer, J., & Chasiotis, A. (2003). Congruence of life goals and implicit motives as predictors of life satisfaction: Cross-cultural implications of a study of Zambian male adolescents. Motivation and Emotion, 27(3), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025011815778

Isik, U., Tahir, O. E., Meeter, M., Heymans, M. W., Jansma, E. P., Croiset, G., & Kusurkar, R. A. (2018). Factors influencing academic motivation of ethnic minority students: A review. SAGE Open, 8(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018785412

Job, V., & Brandstätter, V. (2009). Get a taste of your goals: Promoting motive–goal congruence through affect-focus goal fantasy. Journal of Personality, 77(5), 1527–1560. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00591.x

Kehr, H. M. (2004). Integrating implicit motives, explicit motives, and perceived abilities: The compensatory model of work motivation and volition. The Academy of Management Review, 29(3), 479–499. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159055

Koestner, R., Weinberger, J., & McClelland, D. C. (1991). Task-intrinsic and social-extrinsic sources of arousal for motives assessed in fantasy and self-report. Journal of Personality, 59(1), 57–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00768.x

Ma, X. (2001). Participation in advanced mathematics: Do expectation and influence of students, peers, teachers, and parents matter? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26(1), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2000.1050

Manganelli, S., Cavicchiolo, E., Lucidi, F., Galli, F., Cozzolino, M., Chirico, A., & Alivernini, F. (2021). Differences and similarities in adolescents’ academic motivation across socioeconomic and immigrant backgrounds. Personality and Individual Differences, 182, 111077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111077

Massey, E. K., Gebhardt, W. A., & Garnefski, N. (2008). Adolescent goal content and pursuit: A review of the literature from the past 16 years. Developmental Review, 28(4), 421–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2008.03.002

McClelland, D. C. (1975). Power: The inner experience. Irvington.

McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R. A., & Lowell, E. L. (1953). The achievement motive. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

McClelland, D. C., Koestner, R., & Weinberger, J. (1989). How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ? Psychological Review, 96(4), 690–702. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295X.96.4.690

McClelland, D. C., Koestner, R., & Weinberger, J. (1992). How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ. In C. P. Smith, J. W. Atkinson, D. C. McClelland, & J. Veroff (Eds.), Motivation and personality: Handbook of thematic content analysis (pp. 49–72). Cambridge University Press.

Miller, D. C., & Byrnes, J. P. (2001). To achieve or not to achieve: A self-regulation perspective on adolescents’ academic decision making. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(4), 677–685. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.4.677

Pang, J. S. (2010). Content coding methods in implicit motive assessment: Standards of measurement and best practices for the picture story exercise. In O. C. Schultheiss & J. C. Brunstein (Eds.), Implicit motives (pp. 119–150). University Press.

Pang, J. S., Villacorta, M. A., Chin, Y. S., & Morrison, F. J. (2009). Achievement motivation in the social context: Implicit and explicit hope of success and fear of failure predict memory for and liking of successful and unsuccessful peers. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(6), 1040–1052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.08.003

Pohlmann, K., & Brunstein, J. C. (1997). GOALS: A questionnaire for assessing life goals. Diagnostica, 43, 63–79.

Rawolle, M., Schultheiss, M., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2013). Relationships between implicit motives, self-attributed motives, and personal goal commitments. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 923. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00923

Rawolle, M., Wallis, M. S., Badham, R., & Kehr, H. M. (2016). No fit, no fun: The effect of motive incongruence on job burnout and the mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 65–68.

Roisman, G. I., Masten, A. S., Coatsworth, J. D., & Tellegen, A. (2004). Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child Development, 75(1), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00658.x

Rönkkö, M., & Cho, E. (2020). An updated guideline for assessing discriminant validity. Organizational Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120968614

Schönbrodt, F. D., Hagemeyer, B., Brandstätter, V., Czikmantori, T., Gröpel, P., Hennecke, M., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2021). Measuring implicit motives with the picture story exercise (PSE): Databases of expert-coded German stories, pictures, and updated picture norms. Journal of Personality Assessment, 103(3), 392–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2020.1726936

Schüler, J. (2010). Achievement incentives determine the effects of achievement-motive incongruence on flow experience. Motivation and Emotion, 34(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-009-9150-4

Schüler, J., Baumann, N., Chasiotis, A., Bender, M., & Baum, I. (2019). Implicit motives and basic psychological needs. Journal of Personality, 87(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12431

Schüler, J., Brandstätter, V., Wegner, M., & Baumann, N. (2015). Testing the convergent and discriminant validity of three implicit motive measures: PSE, OMT, and MMG. Motivation and Emotion, 39(6), 839–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9502-1

Schüler, J., Wegner, M., & Knechtle, B. (2014). Implicit motives and basic need satisfaction in extreme endurance sports. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 36(3), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2013-0191

Schüler, J., Zimanyi, Z., & Wegner, M. (2019). Paved, graveled, and stony paths to high performance: Theoretical considerations on self-control demands of achievement goals based on implicit and explicit motives. Performance Enhancement & Health, 7(1–2), 100146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peh.2019.100146

Schultheiss, O. C., & Brunstein, J. C. (1999). Goal imagery: Bridging the gap between implicit motives and explicit goals. Journal of Personality, 67, 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00046

Schultheiss, O. C., Jones, N. M., Davis, A. Q., & Kley, C. (2008). The role of implicit motivation in hot and cold goal pursuit: Effects on goal progress, goal rumination, and emotional well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(4), 971–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.12.009

Schultheiss, O. C., Liening, S. H., & Schad, D. (2008). The reliability of a Picture Story Exercise measure of implicit motives: Estimates of internal consistency, retest reliability, and ipsative stability. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(6), 1560–1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.07.008

Schultheiss, O. C., Rösch, A. G., Rawolle, M., Kordik, A., & Graham, S. (2010). Implicit motives: Current topics and future directions. In T. C. Urdan & S. A. Karabenick (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement (16 Part A) (pp. 199–233). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Shane, J., Heckhausen, J., Lessard, J., Chen, C., & Greenberger, E. (2012). Career-related goal pursuit among post-high school youth: Relations between personal control beliefs and control strivings. Motivation and Emotion, 36(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9245-6

Sheldon, K. M. (2014). Becoming oneself: The central role of self-concordant goal selection. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18, 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314538549

StataCorp. (2013). Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. StataCorp LC.

Thrash, T. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2002). Implicit and self-attributed achievement motives: Concordance and predictive validity. Journal of Personality, 70(5), 729–755. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.05022

Thrash, T. M., Maruskin, L. A., & Martin, C. C. (2012). Implicit-explicit motive congruence. The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0009

Villarreal, B., Heckhausen, J., Lessard, J., Greenberger, E., & Chen, C. (2015). High-school seniors’ college enrollment goals: Costs and benefits of ambitious expectations. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.0120140-1971/©

Vuolo, M., Mortimer, J. T., & Staff, J. (2014). Adolescent precursors of pathways from school to work. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(1), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12038.Adolescent

Winter, D. C. (1994). Manual for scoring motive imagery in running text (Version 4.2). Winter.

Woike, B. A. (2008). A functional framework for the influence of implicit and explicit motives on autobiographical memory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(2), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868308315701

Yau, P. S., Shane, J., & Heckhausen, J. (2021). Developmental goals during the transition to young adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 45(6), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/01650254211007564

You, S., Hong, S., & Ho, H. Z. (2011). Longitudinal effects of perceived control on academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 104(4), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671003733807

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yau, P.S., Cho, Y., Kay, J. et al. The effect of motive-goal congruence on adolescents’ academic goal engagement and disengagement. Motiv Emot 46, 447–460 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-022-09946-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-022-09946-1