Abstract

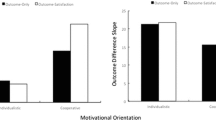

Negotiators in regulatory fit report feeling right about an upcoming negotiation more than those in non-fit, and this intensifies their responses to negotiation preparation (Appelt et al. in Soc Cogn 27(3), 365–384, 2009). High assessors emphasize critical evaluation and being right (Higgins et al. in Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol 35, pp 293–344, 2003). This emphasis should motivate them to engage in correction processes when they only feel right—so strongly as to produce elimination, and perhaps even overcorrection, of the fit effects found previously. We found that low assessors replicated regulatory fit effects on negotiation preparation measures of anticipated performance and perceived assessment competence. For high assessors, however, these fit effects were eliminated and even reversed to some extent. This is consistent with the prediction that high assessors correct because they want to be right, and not just feel right, and correcting can result in overcorrection. Implications for understanding the trade-offs of a strong assessment orientation are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We thank a reviewer for suggesting this additional motivation for high assessors.

This prediction assumes that negotiators generally respond positively to their situation. For each of the four dependent variables of interest, one-sample t-tests indicated that negotiators rated themselves significantly higher than the mid-point of the scale (all ps ≤ .001). Thus, the negotiators generally anticipated good performances and perceived themselves as able to assess their positions.

The two-way interactions with assessment (Regulatory Focus × Assessment and Role × Assessment) were not significant in any of our regressions and thus will not be discussed further.

The interactions with locomotion (Regulatory Focus × Locomotion, Role × Locomotion, and Regulatory Focus × Role × Locomotion) did not produce consistently significant results. The three-way interaction was notably non-significant indicating that, as predicted, locomotion did not moderate focus-role fit. Moreover, because the locomotion interactions did not change the pattern of results, they were excluded.

For conceptual clarity, we divided the four questions into two dependent variables. Analyses using a single composite dependent variable (Cronbach’s α = .71) yielded the same pattern of results with even greater significance.

To ensure this was not merely a halo effect due to positive mood or positive state-of-mind, we regressed anticipated performance on affective state (the average of mood and state-of-mind, r(101) = .71, p < .001). Affective state significantly predicted anticipated performance, B = 0.63, SE = 0.08, t(99) = 7.56, p < .001. We regressed the residuals on our regular set of predictors. Regulatory Focus × Role × Assessment significantly predicted the remaining variance in anticipated performance, B = −0.16, SE = 0.08, t(92) = −2.02, p < .05. In a conservative test of our hypothesis, the three-way interaction had an effect over and above positive mood and positive state-of-mind.

For low assessors, we conducted a regression that shifted the zero value for standardized assessment to +1 SD. For high assessors, we shifted the zero value for standardized assessment to −1 SD.

To again rule out a halo effect due to positivity, we regressed perceived assessment competence on affective state. Affective state was a significant predictor, B = 0.47, SE = 0.07, t(99) = 6.45, p < .001. We regressed the residuals on our regular set of predictors. Regulatory Focus × Role × Assessment marginally significantly predicted the remaining variance in anticipated performance, B = −0.16, SE = 0.09, t(92) = −1,87, p = .06. In a conservative test of our hypothesis, the three-way interaction had an effect over and above that of mood and state-of-mind.

References

Appelt, K. C., & Higgins, E. T. (2010). My way: How strategic preferences vary by negotiator role and regulatory focus. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, in press.

Appelt, K. C., Zou, X., Arora, P., & Higgins, E. T. (2009). Regulatory fit in negotiation: Effects of “prevention-buyer” and “promotion-seller” fit. Social Cognition, 27(3), 365–384.

Avnet, T., & Higgins, E. T. (2003). Locomotion, assessment and regulatory fit: Value transfer from “How” to “What”. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 525–530.

Benjamin, L., & Flynn, F. J. (2006). Leadership style and regulatory mode: Value from fit? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100, 216–230.

Brodscholl, J. C., Kober, H., & Higgins, E. T. (2007). Strategies of self-regulation in goal attainment versus goal maintenance. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 628–648.

Camacho, C. J., Higgins, E. T., & Luger, L. (2003). Moral value transfer from regulatory fit: What feels right is right and what feels wrong is wrong. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 498–510.

Cesario, J., Grant, H., & Higgins, E. T. (2004). Regulatory fit and persuasion: Transfer from “feeling right”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 388–404.

Cesario, J., Higgins, E. T., & Scholer, A. A. (2007). Regulatory fit and persuasion: Basic principles and remaining questions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 444–463.

Crowe, E., & Higgins, E. T. (1997). Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: Promotion and prevention in decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69, 117–132.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1990). Action phases and mind-sets. In E. T. Higgins & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior (Vol. 2, pp. 53–92). New York: Guilford Press.

Grant, H., & Higgins, E. T. (2003). Optimism, promotion pride, and prevention pride as predictors of quality of life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1521–1532.

Heckhausen, H., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1987). Thought contents and cognitive functioning in motivational versus volitional states of mind. Motivation and Emotion, 11, 101–120.

Higgins, E. T. (1996). Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 133–168). New York: Guilford.

Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52, 1280–1300.

Higgins, E. T. (2000). Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist, 55, 1217–1230.

Higgins, E. T. (2005). Value from regulatory fit. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 209–213.

Higgins, E. T. (2006). Value from hedonic experience and engagement. Psychological Review, 113, 439–460.

Higgins, E. T. (2008). Culture and personality: Variability across universal motives as the missing link. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 1–27.

Higgins, E. T., Friedman, R. S., Harlow, R. E., Idson, L. C., Ayduk, O. N., & Taylor, A. (2001). Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: Promotion pride versus prevention pride. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 3–23.

Higgins, E. T., Kruglanski, A. W., & Pierro, A. (2003). Regulatory mode: Locomotion and assessment as distinct orientations. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 35, pp. 293–344). New York: Academic Press.

Higgins, E. T., Pierro, A., & Kruglanski, A. W. (in press). Re-thinking culture and personality: How self-regulatory universals create cross-cultural differences. In R. M. Sorrentino and S. Yamaguchi (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition across cultures. New York: Academic Press.

Jarvis, W. B. G., & Petty, R. E. (1996). The need to evaluate. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(1), 172–194.

Koenig, A. M., Cesario, J., Molden, D. C., Kosloff, S., & Higgins, E. T. (2009). Incidental experiences of regulatory fit and the processing of persuasive appeals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1342–1355.

Kruglanski, A. W., Pierro, A., & Higgins, E. T. (2007a). Regulatory mode and preferred leadership styles: How fit increases job satisfaction. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29(2), 137–149.

Kruglanski, A. W., Pierro, A., Higgins, E. T., & Capozza, D. (2007b). “On the move” Or “Staying put”: Locomotion, need for closure, and reactions to organizational change. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37(6), 1305–1340.

Kruglanski, A. W., Thompson, E. P., Higgins, E. T., Atash, M. N., Pierro, A., Shah, J. Y., et al. (2000). To “Do the right thing” or to “Just do it”: Locomotion and assessment as distinct self-regulatory imperatives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 793–815.

Kuhl, J. (1985). Volitional mediation of cognition-behavior consistency: Self-regulatory processes and action versus state orientation. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckman (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 101–128). Berlin: Sprinter-Verlag.

Kumashiro, M., Rusbult, C. E., Finkenauer, C., & Stocker, S. L. (2007). To think or to do: The impact of assessment and locomotion orientation on the Michelangelo phenomenon. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24(4), 591–611.

Lewin, K., Dembo, T., Festinger, L., & Sears, P. S. (1944). Level of aspiration. In J. McHunt (Ed.), Personality and the behavior disorders (Vol. 1, pp. 333–378). New York: Ronal Press.

Martin, L. L. (1986). Set/reset: Use and disuse of concepts in impression formation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 493–504.

Miller, G. A., Galanter, E., & Pribram, K. (1960). Plans and the structure of behavior. New York: Holt.

Murphy, S. T., & Zajonc, R. B. (1993). Affect, cognition, and awareness: Affective priming with optimal and suboptimal stimulus exposures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 723–739.

Petty, R. E., Wegener, D. T., & White, P. H. (1998). Flexible correction processes in social judgment: Implications for persuasion. Social Cognition, 16(1), 93–113.

Pierro, A., Kruglanski, A. W., & Higgins, E. T. (2006a). Progress takes work: Effects of the locomotion dimension on job involvement, effort investment, and task performance in organizations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(7), 1723–1743.

Pierro, A., Kruglanski, A. W., & Higgins, E. T. (2006b). Regulatory mode and the joys of doing: Effects of ‘locomotion’ and ‘assessment’ on intrinsic and extrinsic task motivation. European Journal of Personality, 20, 355–375.

Pierro, A., Leder, S., Manneti, L., Higgins, E. T., Kruglanski, A. W., & Aiello, A. (2008). Regulatory mode effects on counterfactual thinking and regret. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 321–329.

Schwarz, N., & Bless, H. (1992a). Assimilation and contrast effects in attitude measurement: An inclusion/exclusion model. Advances in Consumer Research, 19, 72–77.

Schwarz, N., & Bless, H. (1992b). Constructing reality and its alternatives: An inclusion/exclusion model of assimilation and contrast effects in social judgment. In L. L. Martin & A. Tesser (Eds.), The construction of social judgments. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (1983). Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(3), 513–523.

Strack, F., & Deutsch, R. (2004). Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 220–247.

Thompson, M. M., Naccarato, M. E., & Parker, K. E. (1989, June). Assessing cognitive need: The development of the personal need for structure and personal fear of invalidity scales. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Psychological Association, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgments under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185, 1124–1131.

Wegener, D. T., & Petty, R. E. (1995). Flexible correction processes in social judgment: The role of naive theories in corrections for perceived bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 36–51.

Wegener, D. T., & Petty, R. E. (1997). The flexible correction model: The role of naive theories of bias in bias correction. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 141–208). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by grants from the National Science Foundation (grant BCS-0415583) and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant 39429), both to E. Tory Higgins. We would like to thank Abby Scholer for her statistical consulting and Karen Lopata, Allison Gross, Matt Siblo, and Katharine Atterbury for their assistance with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Appelt, K.C., Zou, X. & Higgins, E.T. Feeling right or being right: When strong assessment yields strong correction. Motiv Emot 34, 316–324 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-010-9171-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-010-9171-z