Abstract

An air quality modeling system was used to simulate the effects on ozone concentration in the northeast USA from climate changes projected through the end of the twenty-first century by the National Center for Atmospheric Research’s (NCAR’s) parallel climate model, a fully coupled general circulation model, under a higher and a lower scenario of future global changes in concentrations of radiatively active constituents. The air quality calculations were done with both a global chemistry-transport model and a regional air quality model focused on the northeast USA. The air quality simulations assumed no changes in regional anthropogenic emissions of the chemical species primarily involved in the chemical reactions of ozone creation and destruction, but only accounted for changes in the climate. Together, these idealized global and regional model simulations provide insights into the contribution of possible future climate changes on ozone. Over the coming century, summer climate is projected to be warmer and less cloudy for the northeast USA. These changes are considerably larger under the higher scenario as compared with the lower. Higher temperatures also increase biogenic emissions. Both mean daily and 8-h maximum ozone increase from the combination of three factors that tend to favor higher concentrations: (1) higher temperatures change the rates of reactions and photolysis rates important to the ozone chemistry; (2) lower cloudiness (higher solar radiation) increases the photolysis reaction rates; and (3) higher biogenic emissions increase the concentration of reactive species. Regional model simulations with two cumulus parameterizations produce ozone concentration changes that differ by approximately 10%, indicating that there is considerable uncertainty in the magnitude of changes due to uncertainties in how physical processes should be parameterized in the models. However, the overall effect of the climate changes simulated by these models – in the absence of reductions in regional anthropogenic emissions – would be to increase ozone concentrations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Ground-level ozone concentrations present a continuing air quality problem in the northeast USA. Many areas, particularly near the coast, currently are designated as ozone non-containment areas (http://www.epa.gov/ozonedesignations/statedesig.htm), indicating that they have exceeded the national 8-h standard of 0.08 ppm during a recent 3-year period. Ozone concentrations are determined by a number of factors, including local emissions, atmospheric transport of chemical species by the wind, and local meteorological conditions, such as temperature and radiation. The combination of high temperatures, low wind speeds, and lack of cloudiness (high solar radiation levels) is particularly conducive to high ozone levels.

Measures to control ozone concentrations by reducing local and regional emissions can be quite effective. However, the formulation of such measures assumes stable climate conditions. Increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide are changing the radiative balance of the earth–atmosphere system and may result in substantial climate changes in the future. Indeed, model simulations produce global temperature changes of 1.5–4.5°C for a doubling of carbon dioxide (CO2), a level that will be reached during the twenty-first century if current trends continue (IPCC 2001). By the period 2070–2099 the northeast USA is expected to see average summer temperature increases of 2.4°C under a lower emissions scenario and 5.9°C under a higher emissions scenario (Hayhoe et al. 2007). These temperature projections represent the average of projections from three global climate models for the IPCC SRES higher (A1FI) and lower (B1) emissions scenarios (Nakicenovic et al. 2000): HadCM3 (Pope et al. 2000), GFDL CM2.1 (Delworth et al. 2006), and PCM (Washington et al. 2000). Such changes could affect ozone concentrations and the number of days exceeding the national standard due to the sensitive dependence on temperature (e.g., Wuebbles et al. 1989; Sillman and Samson 1995). These potential future changes in climate are driven in large part by global changes in long-lived and well-mixed radiatively active constituents. By contrast, regional emissions of species that are involved in the chemistry of ozone may not have a large effect on climate, either because the spatial scale over which the emissions occur is too small or the lifetime of the species is too short to have a measurable effect on the global climate system, or both. Thus, it is possible that global concentrations of radiatively active constituents and regional emissions of species involved in ozone chemistry could exhibit different future changes.

There have been several prior studies to develop downscaled estimates of the ozone response to climate change in the Northeast that either used a coupled global/regional-scale modeling system (but with no effects of chemistry outside the region examined; Hogrefe et al. 2004) or global-scale chemistry-transport modeling (Murazaki and Hess 2006). Here, we use a state-of-the-art multi-scale climate and chemistry modeling system that accounts for climate and chemistry effects at all scales to examine the potential impact of future climate change on ozone concentrations. The studies presented here are idealized simulations designed to isolate the specific contribution that climate change could have on ozone under the present-day regional emissions directly from anthropogenic sources of species involved in ozone chemistry.

2 Methods

The modeling system consists of a regional climate model (RCM), an emissions model (EM), a global chemistry transport model (GCTM), and a regional air quality model (AQM). Figure 1 shows the modeling domain used by the regional models for this study; it consists of a coarse grid domain with a grid resolution of 90 km and a nested domain with a grid resolution of 30 km. The non-oceanic grids are used for computing the domain average. Further details on the modeling system and the verification of the modeling system relative to current levels of ozone are provided in Huang et al. (2007). Huang et al. (2007) states “Based on analyses for several urban and rural areas and regional domains, fairly good agreement with observations was found for the diurnal cycle and for several multi-day periods of high ozone episodes. Even better agreement occurred between monthly and seasonal mean quantities of observed and model-simulated values. This is consistent with an RCM designed primarily to produce good simulations of monthly and seasonal mean statistics of weather systems.”

The RCM is based on the fifth-generation Penn State University/National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) mesoscale modeling system (MM5) version 3 (Dudhia et al. 2000). For regional climate applications, a buffer zone treatment, ocean interface, and improved cloud-radiation interactions (Liang et al. 2001, 2004a) have been incorporated.

The EM adopted for this study is the sparse matrix operator kernel emissions (SMOKE) modeling system (Houyoux et al. 2000) that processes the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) National Emission Inventory (NEI). It computes gridded, temporalized, speciated emissions in four data categories: point, area, mobile, and biogenic. The ability of the SMOKE system to realistically simulate the emissions pattern in the Midwest USA has been demonstrated (Williams et al. 2001).

The AQM was developed from the SARMAP air quality model (SAQM; Chang et al. 1997), which evolved from the regional acid deposition model (RADM; Chang et al. 1987). The SAQM is a modeling component of the San Joaquin Valley Air Quality Study/Atmospheric Utilities Signatures, Predictions and Experiments Study (SJVAQS/AUSPEX) Regional Modeling Adaptation Project (SARMAP; Ranzieri and Thuillier 1991). The SAQM has been used successfully to study the elevated O3 problem in the Central Valley of California (USA). The AQM, an improved version of the original SAQM, includes a faster, more accurate numerical scheme for solving gas-phase chemistry (Huang and Chang 2001) as well as an aerosol module. In this study, the aerosol module was turned off because of computational constraints.

The GCTM employed here is MOZART-2.4 (Horowitz et al. 2003), which simulates 63 species, 135 gaseous reactions and 26 heterogeneous processes at the global scale and includes a global emissions database for the species involved in ozone chemistry. The advection, surface emission/deposition, vertical diffusion, convection, cloud/precipitation and chemistry are integrated in order every 15 min. The model simulations were conducted with the T42LR horizontal resolution (∼2.8° or 300 km) and 18 sigma-pressure hybrid levels. The GCTM simulations are independent from the AQM and provide an assessment of the sensitivity of the local ozone-climate relationships to long-range transport of pollutants, particularly from East Asia.

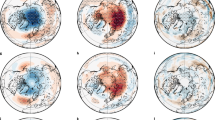

The GCTM and RCM simulations were driven by climate output from the parallel climate model (PCM; Washington et al. 2000), a low climate sensitivity model (Kunkel and Liang 2005). The RCM downscaling can significantly reduce PCM biases in simulating the present climate and this improvement has important consequences for future projections of regional climate changes (Liang et al. 2006). PCM simulations were available for two emissions scenarios described in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (Nakicenovic et al. 2000), the A1FI (high emissions case: with CO2 concentrations reaching ∼970 ppm by 2100) and the B1 (low emissions case: with CO2 concentrations of ∼550 ppm by 2100), hereafter denoted as “high” and “low”, respectively. The coupled modeling system was run for five present-day (control) summers (1996–2000) and five future summers (2095–2099). In addition, studies have shown that the RCM-simulated summer climate is quite sensitive to the choice of cumulus parameterization (Liang et al. 2004b, 2006). Liang et al. (2004b) demonstrated the importance of cumulus parameterization schemes in simulating the diurnal cycle of summer continental precipitation. To assess the effect of the cumulus scheme on the results, two RCM simulations were performed for each climate, one using the Grell cumulus scheme (Grell 1993) and the other using the Kain–Fritsch scheme (Kain and Fritsch 1993), hereafter denoted as “Grell” and “K-F”, respectively. The Grell scheme is very responsive to large-scale tropospheric forcing whereas the K-F scheme is heavily influenced by boundary layer forcing. The K-F scheme tends to produce a vertical heating profile that warms and dries too much near the cloud base. This can ultimately affect surface temperature through turbulent mixing at the top of the planetary boundary layer (Liang et al. 2006), and thus produces larger surface warming than the GR scheme under both high and low emissions scenarios (Fig. 2a). These differences in both precipitation diurnal cycle and surface temperature warming eventually control local ozone responses through processes including photochemical production, aqueous chemistry, wet deposition, and boundary layer mixing.

Future summers (2095–2099) minus control summers (1996–2000) climate conditions for a temperature, b cloud cover fraction, and c wind speed for A1FI (high) and B1 (low) emissions scenarios and for the Grell and K-F cumulus scheme as simulated by the regional climate model. Results are for the grid points representing the five urban areas of the northeast USA whose climate changes are given in Table 1

The AQM and GCTM simulations examined the impact of climate change on ozone concentrations using present-day values of anthropogenic (power plants, industry, transportation, etc.) emissions of species involved in ozone chemistry. However, biogenic emissions from vegetation, based on land-use categories, were allowed to change in response to climate changes in the regional AQM, but not in the global GCTM. At the present time, it is difficult to project the specific aspects of future land-use changes, a topic of on-going research. Therefore, the pattern of future land-use is assumed to be the same as that in the present climate. Each AQM and GCTM simulation covered an entire summer (June through August) over the period of 5 years. Seasonal mean daily and daytime ozone values were calculated for the northeast USA region shown in Fig. 1. Each future simulation was compared with the control simulation to assess projected changes in ozone concentrations.

3 Results

The changes in surface temperature, cloud cover, water vapor and surface wind speed (conditions likely to impact air quality) between the control and future simulations are substantial (Fig. 2). In this and later figures (and in Table 1), “high Grell” means the AQM result driven by the meteorology of the RCM using the Grell scheme downscaled from the PCM future climate under the IPCC high (A1FI) emissions scenario. A similar statement applies for “low Grell”, but using the low B1 emissions scenario. Although the low sensitivity of the PCM model leads to relatively conservative global-scale temperature projections as compared with simulations from other global climate models, projected regional temperature increases from the RCM using PCM simulations as boundary conditions vary from 1 to about 5°C depending on the emissions scenario and the choice of cumulus parameterization scheme. Temperature changes for the high scenario are a factor of 2 or more greater than for the low scenario. The changes are also about 1.5°C larger for the K-F scheme than for the Grell scheme. Cloud cover fraction decreases in all simulations, meaning that incoming solar radiation increases. The fractional changes vary from a little less than 0.02 to about 0.04. Mean model-simulated cloud cover fraction is about 0.3 and these values represent percentage decreases in the range of 8–14%. As for temperature, the cloud cover decreases again are larger for the high scenario than for the low scenario. The changes in wind speed are mixed. For the high emissions scenario, the wind speed decreases by about 0.1–0.2 ms−1 while an increase (little change) of 0.7 ms−1 is simulated for the low scenario with the K-F (Grell) cumulus scheme.

Climate and ozone changes for four major metropolitan areas located near the Atlantic coast and one inland city (Buffalo, NY) are listed in Table 1. Projected temperature changes across these metropolitan areas are very similar in most cases. The largest differences occur for the low K-F simulation in which the temperature increase at Buffalo is 0.9–1.7°C less than at the other areas. Differences in cloud cover changes are small for the two Grell simulations but larger for the K-F simulations. There is an apparent north-south gradient in changes for the K-F simulations; the changes are smallest for Washington, DC/Baltimore and Philadelphia and quite large for Boston. Differences in wind speed change are quite small for all simulations. Interestingly, there is a north-south gradient in the ozone changes, with the smallest future changes in the north and the largest future increases for Washington, DC/Baltimore. There are no corresponding systematic gradients in the climate data, indicating more complex interactions that should be explored in future research. The differences between daily mean ozone and maximum 8-h are quite small.

Figure 3 shows the fractional changes (expressed as percentage of future emissions relative to the present emissions) of biogenic emissions due to the changes in the future climate (2090s). The increases of isoprene emissions ranged from 13 to 57% (from the low to the high scenarios). The relative isoprene emission increases are consistent with the temperature increases because isoprene emissions by vegetation are a function of temperature and incident solar radiation (Guenther et al. 1994, 1995). The changes in isoprene emissions are higher for the high scenario, consistent with the higher temperatures and lower cloud cover fraction (Fig. 2). In addition, the isoprene emissions are higher for the K-F scheme than the Grell scheme, which is also consistent with the higher temperatures and lower cloud cover fractions in the K-F simulations (Fig. 2). The fractional changes of other biogenic species (monoterpenes and other reactive carbon compounds) emissions are similar to that of isoprene emissions.

The fractional changes (percent) of biogenic emissions due to climate changes from present climate (1996–2000) to future climate (2095–2099) for four air quality model simulations in the northeastern subdomain. Each color represents a chemical species labeled in the upper right box with the following definitions (HC3 alkenes whose hydroxyl radical reactivity is low, OLI internal alkenes, NO nitrogen oxide, TERPB terpenes)

Figure 4 shows the fractional changes of daily mean ozone and daily maximum 8-h average ozone averaged over the northeast subdomain and the period of five summers from present to future climate. The changes of daily mean ozone (1.3–27.7%) and daily maximum 8-h average ozone (1.0–26.1%) are similar. The high K-F simulation exhibited the greatest changes while the low Grell simulation had the least changes. The magnitude of changes for the high Grell and low K-F simulations were similar, 11–12%. Again, the relative changes are similar to that of temperature changes. It indicates that the future air quality is comparable to that of present-day situation when the future climate is similar to the present climate as shown in the low Grell (Figs 2 and 3). By comparison, the GCTM produces increases of daily mean ozone levels less than 1%, larger for A1FI than B1. Note, however, that the changes in biogenic emissions are not included in the GTCM simulations. Also, the marine air transport effectively dilutes the coastal ozone levels, especially at the grids along the oceanic boundaries, which take up 35% area of the northeast due to the coarse horizontal resolution. Because the emissions of species involved in ozone chemistry were unchanged in future climate simulations, the changes in future climate air quality are proportional to the combined effect of surface temperature and cloud fraction changes. Thus, it is foreseeable that when the anthropogenic emissions are allowed to increase in the higher emission scenarios, as described in the IPCC (2001), that future air quality will likely deteriorate further, especially for high K-F. On the other hand, the air quality could be improved in the lower emission cases, e.g., low Grell. Clearly, further studies incorporating changes in regional emissions from anthropogenic activities and associated air quality legislation and changes in land-use (Loveland et al. 2002; Civerolo et al. 2000; Hale et al. 2006) are needed. In addition, while this study focuses on the June through August months when high ozone episodes and possible violation of the national standards are most likely to occur, the overall warmer climate suggests that it would useful to expand the study to consider additional months.

4 Conclusions

The results from the air quality modeling system provide insights into the possible future changes in ozone arising from climate changes under present-day anthropogenic emissions, offering more detail beyond the low-resolution global model results. The regional summer climate simulations produce warmer and less cloudy conditions for the northeast USA. Temperature increases of about 3–5°C for the higher emissions scenario and about 1–3°C for the lower emissions scenario are simulated. Cloud cover fraction decreases are about 0.03–0.04 for the high emissions scenario and 0.02–0.03 for the low emissions scenario. Wind speed changes are mixed with small decreases for the high emissions scenario and increases for the low emissions scenario. The higher temperatures increase biogenic emissions by about 15–55% for the higher emissions scenario and about 5–20% for the lower emission scenario. Both mean daily and 8-h maximum ozone increase (by about 10–25% for the higher emissions scenario and 0–10% for the lower emissions scenario) from the combination of three factors, all tending to favor higher concentrations: (1) higher temperatures lead to changes in the rates of reactions and photolysis rates important to the ozone chemistry (e.g., more thermal decomposition of peroxyacetyl nitrate (PAN), which leads to more nitrogen oxides (NOx) and odd hydrogen (e.g., OH, HO2, etc) and thus more ozone production in the daytime. Overall the ozone production increases with increased temperature (e.g., Sillman and Samson 1995; Tao et al. 2007); (2) lower cloudiness (higher solar radiation) increases the photolysis reaction rates; and (3) higher biogenic emissions increase the concentration of reactive species used in ozone production.

While the qualitative response of regional ozone concentrations to climate change is quite clear, considerable uncertainty remains regarding the magnitude of changes due to model uncertainties (for example, the two cumulus parameterizations produce ozone concentration changes that differ by approximately 10%) and to an even greater extent, future regional emissions from human activities and related air quality and/or climate change initiatives. Other uncertainties affecting the results presented here include the vertical mixing, particularly in the model treatment of the planetary boundary layer, the effects of land use changes on emissions (e.g., of volatile organic compounds), and the effects of aerosols not accounted for in this study.

References

Chang JS, Brost RA, Isaksen ISA, Madronich S, Middleton P, Stockwell WR, Walcek CJ (1987) A three dimensional Eulerian acid deposition model: physical concepts and formulation. J Geophys Res 92:14681–14700

Chang JS, Jin S, Li Y, Beauharnois M, Lu C-H, Huang H-C, Tanrikulu S, Damassa J (1997) The SARMAP Air Quality Model Final Report. Air Resource Board, California Environmental Protection Agency, Sacramento, California, USA

Civerolo KL, Sistla G, Rao ST, Nowak DJ (2000) The effects of land use in meteorological modeling: implications for assessment of future air quality scenarios. Atmos Environ 34:1615–1621

Delworth TL, Broccoli AJ, Rosati A, Stouffer RJ et al (2006) GFDL’s CM2 global coupled climate models – Part 1 – Formulation and simulation characteristics. J Climate 19:643–674

Dudhia J, Gill D, Guo Y-R, Manning K, Wang W, Chriszar J (2000) PSU/NCAR Mesoscale modeling system tutorial class notes and user’s guide: MM5 modeling system version 3 (http://www.mmm.ucar.edu/mm5/doc.html)

Grell GA (1993) Prognostic evaluation of assumptions used by cumulus parameterizations. Mon Wea Rev 121:764–787

Guenther A, Zimmerman P, Wildermuth M (1994) Natural volatile organic compound emissions rate estimates for U.S woodland landscapes. Atmos Environ 28:1197–1210

Guenther A, Hewitt CN, Erickson D et al (1995) A global model of natural volatile organic compound emissions. J Geophys Res 100:8873–8892

Hale RC, Gallo KP, Owen TW, Loveland TR (2006) Land use/land cover change effects on temperature trends at U.S. Climate Normals stations. Geophys Res Lett 33, L11703, DOI 10.1029/2006GL026358

Hayhoe K, Wake C, Huntington TG, Luo L et al (2007) Past and future changes in climate and hydrological indicators in the US Northeast. Clim Dyn 28(4):381–407

Hogrefe C, Lynn B, Civerolo K et al (2004) Simulating changes in regional air pollution over the eastern United States due to changes in global and regional climate and emissions. J Geophys Res 109, D22301, DOI 10.1029/2004JD004690

Horowitz LJ, Walters S, Mauzerall DL et al (2003) A global simulation of tropospheric ozone and related tracers: description and evaluation of MOZART-2.4, version 2. J Geophys Res 108(D24):4784 DOI 10.1029/2002JD2853

Houyoux MR, Vukovich JM Jr., Coats CJ, Wheeler NJM, Kasibhatla PS (2000) Emission inventory development and processing for the seasonal model for regional air quality (SMRAQ) project. J Geophys Res 105:9079–9090

Huang H-C, Chang JS (2001) On the performance of numerical solvers for chemistry submodel in three-dimensional air quality models, 1. Box-model simulations. J Geophys Res 106:20175–20188

Huang H-C, Liang X-Z, Kunkel KE, Caughey M, Williams A (2007) Seasonal simulation of tropospheric ozone over the Midwest and Northeast U.S.: an application of a coupled regional climate and air quality modeling system. J Appl Meteor Clim 46:945–960

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Houghton JT, Ding Y, Griggs DJ, Noguer M, van der Linden PJ, Dai X, Maskell K, Johnson CA (eds) (2001) Climate change 2001. The scientific basis. Contributions of Working Group 1 to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 881

Kain JS, Fritsch JM (1993) Convective parameterization in mesoscale models: the Kain–Fritsch scheme. In: The representation of cumulus convection in numerical models. Meteor Monogr, No. 46, AMS, Boston, Massachusetts, pp 165–170

Kunkel KE, Liang X-Z (2005) CMIP simulations of the climate in the central United States. J Climate 18:1016–1031

Liang X-Z, Kunkel KE, Samel AN (2001) Development of a regional climate model for U.S. Midwest applications. Part 1: sensitivity to buffer zone treatment. J Climate 14:4363–4378

Liang X-Z, Li L., Kunkel KE, Ting M, Wang JXL (2004a) Regional climate model simulation of U.S. precipitation during 1982-2002, Part 1: annual cycle. J Climate 17:3510–3528

Liang X-Z, Li L, Dai A, Kunkel KE, (2004b) Regional climate model simulation of summer diurnal precipitation cycle over the United States. Geophys Res Lett 31:L24208

Liang X-Z, Pan J, Zhu J, Kunkel KE, Wang JXL, Dai A (2006) Regional climate model downscaling of the US summer climate and future change. J Geophys Res 111:D10108

Loveland TR, Sohl TL, Stehman SV, Gallant AL, Sayler KL, Napton DE (2002) A strategy for estimating the rates of recent United States land-cover changes. Photogramm Eng Remote Sens 68:1091–1099

Murazaki K, Hess, P (2006) How does climate change contribute to surface ozone change over the United States? J Geophys Res 111:D05301

Nakicenovic NJ et al (2000) Special Report on Emissions Scenarios. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pope VD, Gallani ML, Rowntree PR, Stratton RA (2000) The impact of new physical parameterizations in the Hadley Centre climate model-HadCM3. Clim Dyn 16:123–146

Ranzieri AJ, Thuillier R. (1991) San Joaquin Valley Air Quality Study (SJVAQS) and Atmospheric Utility Signatures, predictions and experiments (AUSPEX): a collaborative modeling program. Proceedings, 84th Annual Meeting of the Air & Waste Management Association, Vancouver, British Columbia, paper 91-70.5

Sillman S, Samson PJ (1995) Impact of temperature on oxidant photochemistry in urban, polluted rural and remote environments. J Geophys Res 100:11497–11508

Tao Z, Williams A, Huang H-C, Caughey M, Liang X-Z (2007) Sensitivity of U.S. surface ozone to future emissions and climate changes. Geophys Res Lett 34:LO8811

Washington WM, Weatherly JW, Meehl GA et al (2000) Parallel climate model (PCM) control and transient simulations. Clim Dyn 16:755–774

Williams A, Caughey M, Huang H-C, Liang X-Z, Kunkel KE, Tao Z, Larson S, Wuebbles DJ (2001) Comparison of emissions processing by EMS95 and SMOKE over the Midwestern U.S. Presentation. 10th International Emission Inventory Conference “One Atmosphere, One Inventory, Many Challenges”, Denver, CO, USEPA, Session 10

Wuebbles DJ, Grant KE, Connell PS, Penner JE (1989) The role of atmospheric chemistry in climate change. J Air Pollut Control Assn 39:22–28

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Center for Atmospheric Research for providing data to drive the global and regional models. We acknowledge the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Forecast Systems Laboratory and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for the supercomputing support. The research was partially supported by the United States Environmental Protection Agency award EPA RD-83096301-0. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the sponsoring agencies or organizations involved, including the Illinois State Water Survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kunkel, K.E., Huang, HC., Liang, XZ. et al. Sensitivity of future ozone concentrations in the northeast USA to regional climate change. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 13, 597–606 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-007-9137-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-007-9137-y