Abstract

Paraprofessional youth care workers in residential treatment centers (RTCs) are responsible for the everyday care, supervision, and treatment of youth with serious behavioral and mental health challenges. Turnover rates among this poorly paid workforce are high, and it is not known why individuals seek and maintain youth care work despite its significant challenges. Following anthropologists who study morality as situated practice, we investigate the role of altruism in recruiting and retaining workers in RTCs. We ask: How do managers and youth care workers understand altruism and its role in youth care work and what are the consequences of those understandings? Through organizational ethnography of an RTC, we show that workers and management understood altruism differently. Managers viewed altruism as an inherent trait of some and attributed turnover to its lack. Although workers sometimes enacted this script, they understood themselves as engaged in far more complex situated moral projects in which altruism was only one part. We demonstrate political effects of these differing understandings of altruism, namely, that management deflected institutional critique by viewing it as a sign of workers’ immorality. We offer modest recommendations for RTCs seeking to recruit and retain competent youth care workers and address potential new directions for moral anthropology of organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maintaining an experienced, adequately trained youth care workforce presents a complex and formidable challenge to residential treatment centers (RTCs) that serve children with psychiatric and behavioral problems (Colton and Roberts 2007). With increasing financial and ethical imperatives to treat children in non-institutional settings, RTCs have—in most Western nations—been cast a treatment of “last resort” for youth who cannot be safely maintained in home-based care. This shift has contributed to higher acuity among youth who do receive residential treatment, making youth care work more challenging than ever (McAdams 2002; Colton and Roberts 2007). At the same time, viewing RTCs as a last resort and necessary evil may also have diminished the esteem of youth care work and youth care workers. Colton and Roberts (2004, in 2007) have argued that residential childcare workers in the UK are considered the “lowest form of social worker” (137) and tend to view this low paid, high stress work as temporary. Residential youth care is characterized by high levels of burnout (Decker, Bailey, and Westergaard 2002; Seti 2007), and annual turnover rates as high as 50% (National Direct Service Workforce Resource Center 2008).

Decker et al. (2002) found that more than half of youth care workers experience moderate to high levels of depersonalization, 22% reported high levels of emotional exhaustion, and 55% reported that they felt low levels of personal achievement in their work. Smith, Colletta, and Bender (2017) found that workers in one RTC regularly experienced violence perpetrated by youth in care, some of which caused serious and lasting injury and/or serious psychosocial consequences. Youth care workers in this study reported that client violence was the most difficult part of their work and contributed to their desire to leave youth care positions.

Staff turnover poses a costly problem for all organizations, but it is especially damaging in residential treatment for two reasons. First, frequent turnover of youth care workers damages the often-tenuous relationships between workers and youth and harms attempts to provide trustworthy and consistent relational care. Such disruptions may also increase dysregulated or violent behavior on the part of youth and disturb the therapeutic milieu as a whole (Colton and Roberts 2007). Second, growing evidence suggests that significant time-in-position is required for youth care workers to develop the practice skills necessary to provide a high level of care (Smith et al. 2017; Pazaratz 2000; Youngren 1991). With the stakes of turnover in RTCs so high, it makes sense to consider why workers leave, but also why they begin youth care work and why they stay.

Although drivers of staff turnover in RTCs are beginning to come into focus, very little is known about factors that attract individuals to youth care work in RTCs or help extend their tenure in these positions. This article presents findings of a 15-month ethnographic study of workforce issues in an RTC in the Northeastern U.S. designed to investigate why workers seek youth care positions and continue on in them under inherently challenging conditions. In particular, this article investigates the claim of administrators in the participating organization that youth care workers seek and continue youth care work out of inherent altruism. We consider the ways that framing youth care workers as altruists affected the organization’s recruiting efforts and their interpretation of workers’ perceived failures and decisions to leave youth care. We also investigate the perspectives of youth care workers themselves, who often claimed altruistic motives for seeking and continuing youth care work but understood the nature of altruism differently. We approach their work as situated moral projects through which youth care workers attempted to construct and maintain valued identities as “good” workers under the complex demands of the organization and the work itself. We found that claims of altruism in youth care work were desirable to management and were even at times intentionally elicited in training activities as a strategy for reducing burnout and vicarious traumatization. As such, workers’ claims of altruism enacted a preferred script, but one that was sometimes at odds with their often far more complex narratives about the moral terrain of their work. We investigate the political effects of these ideological differences in what constitutes moral youth care work, showing that management used the ideology of altruism as an essential property inhering in certain workers to disempower and deflect potentially legitimate critiques of the organization and its policies. Based on these findings, we offer modest recommendations for RTCs seeking to recruit, train, and retain a competent youth care workforce that can maximize the health and safety of both workers and youth in care. We conclude by reflecting on ways that the study of youth care work as a moral laboratory (Mattingly 2014) might contribute to the theory and practice of moral anthropology in organizations.

Background

The Challenges of Youth Care Work

Youth care workers in RTCs are responsible for round-the-clock supervision, care, and treatment of young people with mental illness who cannot be safely cared for in an outpatient setting but do not need inpatient hospitalization. Youth in U.S. RTCs have typically received a range of less intensive mental health services prior to admission or have been “stepped down” from psychiatric hospitalization or involvement with the criminal justice system. Many youth in RTCs are referred through the foster care system. They share in common a determination by mental health professionals, and often family court, that they cannot be adequately treated without round-the-clock supervision by a workforce of professional and paraprofessional caregivers.

The everyday lives of youth care workers (and their clients) in RTCs may seem at first to approximate that of typical children and their caregivers. They prepare and eat dinner, do homework, walk to the public library, and play games together. They engage in family-like verbal exchanges, e.g., “You can’t do your nails until your chore is done.” Youth care workers are expected to develop and maintain stable “therapeutic” relationships with the children in their care, who have often experienced significant disruptions in relationships with past caregivers (Gharabaghi 2014). As Hejtmanek (2015) has described, under some circumstances, youth care workers understand their intimate work as using and cultivating love as a healing agent, a balm for the personal and political violence that RTC residents have experienced prior to and during their confinement in a total institution (Goffman 1961). Enacting this therapeutic form of love is difficult. Work shifts are varied and unpredictable and may include periods of routine, low stress activities—such as playing sports alongside youth, facilitating group interactions, or assisting with activities of daily living—punctuated by unpredictable and sometimes dangerous behavioral crises that workers must manage using verbal de-escalation techniques and, in some cases, physical restraint (Hejtmanek 2010, 2015; Smith 2014). The work requires constant vigilance on the part of youth care workers, who are aware of the potentially profound negative consequences of lapses in attention or inadequate responses (Seti 2007; Smith 2014). Youth workers also experience violence committed against them by the youth in their care, some of which can be serious and cause lasting physical and psychosocial injury (McAdams and Foster 1999; Hejtmanek 2015; Smith et al. 2017). It is difficult to overstate the difficulty of youth care work in RTCs. Yet, despite its challenges, in the U.S., youth care work is not professionalized (National Direct Service Workforce Resource Center 2008), and few organizations require specialized preservice education or training beyond a high school diploma or the equivalent. It is also poorly paid, with average annual wages of just $23,750 (U.S. Department of Labor Statistics 2013).

If youth care work is so difficult, poorly paid, and dangerous, why, then, do individuals continue to seek these positions and stay with them once they are hired? One obvious but underexplored aspect of this puzzle is the accessibility of youth care work. Because most youth care positions require little or no higher education or specialized pre-service training, they are accessible to individuals just entering the workforce after high school, those simultaneously attending college, and others who lack specialized education. In the U.S., for example, residential youth care work has been included in the category of “direct service work” alongside paraprofessional work in addiction treatment, home-based health services, and nursing care facilities, all of which require little or no formal training or education and are among the lowest paying jobs in the nation (Hewitt et al. 2008). Nationally, these jobs are disproportionately filled by women and people of color (Hewitt et al. 2008), reflecting histories of women’s, and especially African American and Latina women’s, limited access to work outside domestic service and caregiving (Duffy 2011; Milkman, Reese, and Roth 1998). Because of its therapeutic orientation, direct care work in residential settings may offer an appealing alternative to similarly paid jobs in fast food restaurants, retail, and unskilled labor. Other market and logistical factors that may also attract individuals to youth care work include unconventional or flexible hours (including evening, weekend, and overnight hours), no requirement of computer literacy, and a low threshold for past work experience.

Rosier than the proposition that youth care workers are simply low skilled individuals seeking the best of poor job opportunities is the hypothesis that individuals may seek and continue youth care work out of a desire for “compassion satisfaction.” Proposed by clinical scholars as a companion to the more widely investigated compassion fatigue (Figley 1995; Pearlman and Saakvitne 1995), compassion satisfaction has been defined as: “pleasure and meaning one derives from being able to do one’s helping work well” (Eastwood and Ecklund 2008:108). Eastwood and Ecklund (2008) found that youth care workers in RTCs had high levels of compassion satisfaction, which were negatively related to burnout levels. Yet, compassion satisfaction did not appear to ameliorate risk level for compassion fatigue. Zerach’s (2013) study of 147 Israeli residential childcare workers found that they reported higher levels of compassion satisfaction than did peers working in residential boarding schools for higher functioning youth. He suggests: “It can be assumed that while [residential youth care workers] may experience high levels of job dissatisfaction, they could also concurrently experience the benefits of helping particularly vulnerable individuals” (84).

Altruism, First Person Virtue Ethics, and Anthropologies of Caring

Indeed, working with the highly vulnerable youth served by RTCs may offer unique opportunities to experience caring-related satisfaction not available in other low-skilled jobs. However, the construct of compassion satisfaction assumes that workers are able to experience pride, satisfaction, and “meaning” through caring for others in need. Why do some individuals seek such experiences even under the exceptionally difficult conditions of youth care work? One way that “helping” work has been understood is as an expression of altruism. Altruism, first attributed to Comte (1855), has preoccupied philosophers, theologians, social theorists, psychologists, and social work scholars who have sometimes viewed altruism as a quality in opposition to self-interest or egoism. Psychologist C. Daniel Batson (1991) follows Comte in defining altruism as “a motivational state with the ultimate goal of increasing another’s welfare” (6). Important to this and most definitions of altruism is that it is viewed as an interior quality or force that motivates particular actions, rather than as those other-directed actions themselves. With altruism figured as a quality that might be expressed in actions but which is not, itself, an action, we are left to imagine that certain individuals possess more or less of it, or that a certain person either is or is not “altruistic.”Footnote 1

Scholars of social work and social services have long grappled with the question of whether social service work and workers are—or ought to be—altruistic. Specht and Courtney (1995) dubbed social workers “unfaithful angels” for abandoning the poor for better-paid work in the private practice of psychotherapy, a move that they framed as a failure of altruism. In the 1990s, scholars relied on particular readings of Foucault to challenge the beneficence of social work and frame its practices as the exertion of social control over the poor and deviant (Chambon, Irving, and Epstein 1999; Margolin 1997; Tice 1998). Michael Lipsky coined the term “street level bureaucrats” to describe front line social service workers who must mediate between policy and organizational pressures and the human objects of those pressures. He has argued that they labor under what he calls a “myth of altruism” (1980:71). He suggests that, although the idea that social service workers ought to be motivated by altruism is inscribed in professional codes of ethics, training curricula, and the language of social policy itself, few ever question whether the effects of social service work are indeed beneficent. While the legitimacy of pursuits like social work is premised upon the myth of workers’ altruism, in reality, Lipsky argues, these alienated street level bureaucrats are better viewed as servants of the conflicting organizational and policy goals they must negotiate.

As we will show, youth care workers in this study understood their work as a moral project—one that called them to perform the altruism from which their managers believed good work ought to flow. And sometimes their work did seem to enact a deeply felt desire to care for and protect vulnerable children—desires grounded in empathy and, perhaps, love. Recent developments in moral anthropology have provided a much-needed bridge between philosophical attention to “universal” moral constructs—like altruism—and the complexly situated experiences of everyday people trying to live “good” lives. Cheryl Mattingly has delineated what she calls a “first-person virtue ethics,” which attends to these situated projects of individuals in local moral terrains (2014:9). She views her informants as undertaking ongoing experiments in the good, struggling to create and sustain workable, moral lives amid structures that often leave open only difficult options and narrow spaces for improvisation (2013, 2014). Her many-year study of African-American women caring for disabled children demonstrates the complicated, demanding, and sometimes crushing moral work of being a good caregiver under nearly impossible circumstances. She illustrates the dense “moral ordinary” within which women experiment with, for example, how to parent a medically fragile child who wants to play soccer among able-bodied peers, or—more devastatingly—how to construct a workable self who can care for a dying child, bury her, “give back” to other families trying to negotiate similar ordeals, and somehow survive, herself. Her work reveals rich (and painful) situated life projects playing out beyond universal philosophical ideals of morality, rigid poststructuralist visions of the care of the self,Footnote 2 and the ideology of virtue as an inherent property of certain individuals.

We are guided also by Brodwin’s studies of community mental health workers engaged in what he calls “everyday ethics” (2013). His work, like Mattingly’s, takes up an empirical middle ground between abstract notions of the good—in his case, the ideals of bioethics—and the messy, unfolding practice situations in which workers must find some ethically acceptable way forward. Through ethnographic study of clinicians engaging in community-based treatment of adults with serious mental illness, he reveals workers engaging the ideals of bioethics—such as confidentiality and self-determination—as they intersect with the particular treatment technologies, organizational pressures, and situated complexity of actual mental health work. His informants are practical moral philosophers who must find ethical ways to act in dynamic, high-stakes circumstances with limited information. They appear as neither “bad workers” nor helpless dupes of the institutions that shape the possibilities for them and their clients. Yet, their situated moral work often leaves them having to compromise between competing ethical principles and having to tolerate profound ambivalence about the goodness of their clinical tactics (Brodwin 2013, 2014).

Although ethnography has recently been used to study a range of moral projects (e.g., Gron 2017; Taylor 2017), most relevant to this study is ethnographic work addressing moral terrains of paid caregiving. Elana Buch’s (2013, 2014) study of home care workers for older adults explores these low-wage work arrangements as sites in which both caregivers and the recipients of “gifts of care” struggle to construct moral ways of interacting within the limits of the agency that manages their relationships. For example, workers were barred from accepting even small gifts from their clients, which administrators (and the criminal justice system) construed as theft. Yet, workers often gave gifts of unpaid work, which served to strengthen relationships with clients and “prove that their labor was motivated by moral rather than mercenary commitments” (2014:14). Buch’s work illustrates a skepticism of the proper motivations of paid caregivers. Even the idea, embedded in contemporary American English, that care is “given” seems to trouble the legitimacy of paid acts of care.Footnote 3

Feminist social work scholar, Melissa Hardesty, has investigated a similar moral landscape in foster care. Foster parents in her study received “board payments” in exchange for caring for children in their homes, a practice whose history is bound up with the U.S.’s historical refusal to treat parenting as a legitimate form of labor. Hardesty’s caseworkers and foster parents demonstrate what she terms “commodification anxiety,” “the fear that sentimental caregiving relationships will be corrupted by money” (2018:94–95). Caseworkers suspect certain foster parents—particularly those whose other earned income is low—of “doing it for the money” and discipline those who appear to treat board payments as pay. In the process, caseworkers reinscribe the idea that parenting should be motivated solely by altruism and that treating caregiving as labor makes caregivers morally suspect. Both Buch’s and Hardesty’s studies demonstrate that even meager pay for acts of care troubles the moral projects of workers who struggle to be viewed as virtuous while engaging in difficult, poorly paid work on behalf of vulnerable others.

Katie Rose Hejtmanek’s (2010, 2014, 2015) study of an RTC program that served and was staffed primarily by African American men provides the nearest account of the moral terrain of youth care work. She argues that workers’ love for residents allows them to suspend or tolerate reactions of disgust and anger when youth engage in what her informants call “crazy shit”—behaviors that involve profound violations of everyday expectations of comportment, such as smearing feces or digging holes in their skin. Following Miller (1997), she argues that this interplay of love and repulsion characterizes the relationship between workers and youth in this context, much as it facilitates parents’ care of infants’ intimate bodily functions. What her informants, translating ill-fitting psychiatric models into a “hiphopified” vernacular, call “mad love” is a political act, a counterbalance to the ongoing harms of white supremacy. Counter to studies that have sometimes flattened the moral terrain of care work into poststructuralist frameworks, she argues that it is love, and not the panoptic gaze, that is internalized through living at “Havenwood.” Even the most violent and intimate of physical interactions—manual restraint—is framed by informants as loving and protective. Although this work focuses on tactics of therapeutic translation that exploit “gives” in a potentially rigid system of treating young Black men, her focus on love as a necessary counterpoint to violence resonates with the present study.

Methods

We see in the tradition of moral anthropology a way to analyze an unexpected finding of this study: Both management and youth care workers made strong, though differing, arguments that good youth care work—and good youth care workers—were motivated by altruism. This was true even though all involved were keenly attuned to the economic transactions of paid labor that made their acts of care instrumental in at least one sense. Following Mattingly and other scholars of situated morality, we take a single RTC for youth as a moral laboratory in which youth care workers experiment with what it means to provide “good” care for the distressed, emotionally disturbed, and sometimes violent youth they are paid to serve. We seek to develop a thick account (Mattingly 2014; Geertz 1973) of the moral landscape that shapes notions of the good in this organizational culture as well as the exigencies to which workers must respond in their projects of moral becoming. At the same time, we follow the phenomenological impulse of Mattingly’s work in our attention to the accounts of informants, even when they reflect seemingly contradictory moral schemes coexisting in a single site of practice.

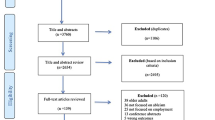

The findings presented here are derived from a 15-month ethnographic study of “Promise,”Footnote 4 an RTC located in the Northeastern U.S. that serves emotionally disturbed youth ages 7–18 placed by the child welfare system. After filing a protocol for human subjects protection with the Syracuse University IRB, data collection began in August of 2015 and concluded in November of 2016. All youth care workers, program managers, clinical professionals, and executive level managers were invited to participate in participant observation and individual interviews. No fieldnotes were made about workers who did not consent to participant observation, although they were at times present. Similarly, no data were collected about Promise clients as they were not the focus of this study, but the first author worked with participating program managers to inform clients about the study and about their right to ask the researchers to leave at any time. The researchers did not supervise or treat clients and were at no time alone with them.Footnote 5

Assisted by the third author, the first author conducted 15 months of participant observation of work activities at Promise, including staff meetings, training activities, special events (such as a public job fair and staff appreciation picnic), and everyday youth care practice in the residential milieu. Of particular relevance to this article was participant observation of recruiting activities and training in “Risking Connection,” a curriculum in trauma-informed care, which intentionally elicited from workers narratives about compassion satisfaction. Participant observation was documented daily using concurrent and/or post-observation fieldnotes as well as audio-recorded voice memos when computer use was not feasible. Fieldnotes were reviewed regularly by the first author, who used periodic research memos to identify emerging themes related to the research questions.

The first and third authors conducted 65 individual semi-structured interviews with Promise employees, including management, clinical staff (e.g., social workers, psychologist), “staff development professionals” in the training department, and youth care workers in all residential programs. At the request of agency administrators who were interested to learn more about why long term employees chose to stay, we sought to oversample youth care workers with three or more years of experience and completed 24 such “stay” interviews. In most cases, participants were asked to describe how they came to work in residential treatment, what they most enjoyed about their work, and what was the most difficult part of their job. However, interview questions were developed iteratively during individual interviews and throughout the study in response to emerging themes and working hypotheses. Of particular relevance to this article are questions regarding workers’ reasons for seeking youth care work and reasons for continuing in their positions.

Data analysis was conducted continuously during fieldwork through the review of fieldnotes, interview transcripts, and research memos. Following the conclusion of fieldwork, the first and second author used NVivo to more intensively organize and analyze the data. While we used thematic coding to identify relevant large strips of talk from interviews, fieldnotes, and other relevant documents (such as training materials), we did not use data analysis software to search and code decontextualized instances of particular words or phrases. Following Carr (2011), we strived to analyze interview data with attention to the multifaceted contexts in which the utterances were produced, including the organizational setting and immediate context of the interview itself. Throughout data analysis, we remained attuned both to data that supported or nuanced our developing theories about the research questions and data that shifted or challenged those understandings.

Findings and Discussion

The Challenges of Maintaining a “Virtuous” Youth Care Staff

During fieldwork, Promise management struggled to fill a large number of vacant youth care positions in its residential programs. At times, as many as 20% of all youth care positions were vacant, leaving administrators with the challenging task of attracting, interviewing, hiring, and training a continuous stream of new youth care workers for jobs that typically involved undesirable evening, overnight, and weekend hours and paid between $11.60 and $14.90 per hour. Managers and youth care workers frequently acknowledged that this pay rate, though higher than in past years and paired with health insurance and other fringe benefits, was commensurate with fast food or retail work. Managers also acknowledged that they felt they were at times “scraping the bottom of the barrel” of job candidates and forced to hire individuals who were simply “warm bodies,” meaning people who met only the most minimal qualifications for the job. Once hired, youth care workers sometimes left before completing the month-long series of pre-service trainings and supervised practice shifts. Apparently exhausted just by describing the organization’s struggle with staff turnover, Frank, the executive director, explained:

-

Frank: [sighs] So, you know, the economy’s changed, people are getting $15 to flip burgers and, or whatever and, uh, so this is, this is hard work

-

First Author: It is

-

F: And, uh…and we understand that, so everybody’s flying the coop

-

FA: Wow

-

F: And even, you know, we’d lose two up at—hopefully we won’t lose two out of this [training] class but…we used to, we’d probably lose two out of the orientation class, and then…

-

FA: Before they even hit the floor?

-

F: Yeah, one or two before they hit the floor. Something would happen…

-

FA: Wow

-

F: You know, they’ll start showing behavior that we don’t tolerate, you know, whether it’s showing up late, skipping, not showing up at all, you know, those kinds of things. Um, or, you know, somebody at the last one that taped a urine sample to his leg [when] he was going to go take his drug test

When IFootnote 6 asked Frank what he thought contributed to voluntary turnover among youth care workers more generally, he explained:

Boy, um, [long pause] I don’t know. It’s probably, like, a lousy return on investment, you know? They’re expected to put all this time, effort, energy in and you get, you know, little, little personal satisfaction and your paycheck doesn’t look so hot either. Um, so I, I, I, you know, I think that generally—I don’t think the job is what people think it is. You know, I think—I think they’re surprised at the level of, uh, difficulty they have with, with the kids that are in our care. Um, I think that takes a lot of people by surprise.

With halting speech that seemed to reflect his own search for understanding of the problem, Frank suggested that a cost/benefit analysis leads workers to view their employment as a “lousy return on investment.” In his economic explanation of turnover, youth care workers find that the surprisingly high costs of the work itself are not matched by the pay or “personal satisfaction” they derive from it.

Even under these difficult hiring conditions, Promise management had clear priorities in hiring. Executive level managers commonly foregrounded altruism as a desirable or requisite quality of successful youth care workers, an ideology that fit with their acknowledgment that the work was not sufficiently rewarding in a purely economic sense, and perhaps also that they did not believe that it required specialized education or training. They espoused the necessity of altruism in interviews, reiterated it in communications with prospective and newly hired workers, and created a commercial staff recruitment campaign that foregrounded altruism as an esteemed characteristic of youth care workers. In the same early interview with Frank, he emphasized the importance of hiring youth care workers with a desire to help others.

-

Frank: I’m gonna say that, probably, I think people generally—I think people hired come into this because they genuinely want to help. And they genuinely care about these kids. These kids are very difficult to care for. Um, their behaviors are very difficult, you know. I tell people, you have to find something. And it’s hard to do with some kids… But you have to find something about every single kid that you like

-

FA: Yeah

-

F: And you have to build on that. And when a kid is biting you, or spitting on you, or…

-

FA: Yeah

-

R: You know, callin’ ya every name in the book, sometimes it’s hard to, to see the good in all that. And, um, so I think the inability to see the good [is undesirable]

His description of desirable workers—those who “genuinely care about kids”—is a moral discourse. He suggests that the people he wants to hire are drawn to youth care work out of a desire to help kids who are “very difficult to care for” due to their challenging and sometimes violent behavior. He shares with new workers his advice to find likeable qualities in their clients, in spite of their predictably difficult behavior. This advice seems to follow from his belief that “genuine care” for clients and a desire “to help” are what motivate youth care workers to undertake this difficult job. From this perspective, then, an inability to “see the good” in clients—beyond their challenging and dangerous behavior—reveals a failure of the altruistic motivation he believes is necessary for good youth care work. It is also notable that he mentions no particular education, training, experience, or skills beyond this altruistic orientation.

Paul, a former school psychologist and an executive level manager who had worked for the organization for two decades, wanted to be sure that I was able to differentiate between the perspectives of what he saw as the “two types of people” employed by Promise:

-

Paul: Okay. There’s those that want a job and other things

-

First Author: Mm hmm

-

P: And those that want to do this work and work hard

-

FA: Yeah

-

P: And I—and I think that—and I think there are differences. And um, I think that the people that stay here a long time, there’s something similar about them

When I asked him to explain how he differentiated between individuals of these two “types,” he clarified this way:

-

P: It’s, it has to do—I can tell all of these people are—are virtuous people

-

FA: Yeah

-

P: All of these people tend to have impeccable character. Tend to give to others. You can look at [Frank]. [Frank]’s my good Catholic. He’s my executive director. He’s my good Catholic. [Sam] the prior guy, I think, he you know, he was a seminarian

-

FA: Uh huh

-

P: Okay. Um, that’s the past 20 damn darn near 20 years that I’ve had two executive directors that have come through fairly, um, you know, Catholic upbringings and—and giving to others and being really supportive. They’re great leaders

-

FA: Right

-

P: Okay? So I would say that that trait is in the smaller group is in—and of—of people that have, uh, they want to make a difference, okay?

-

FA: Mm hmm

-

P: But do you know how many people will show up if you look for those people? You know, we want to give jobs to people that, you know, want to be, get kicked, spit on, not taking any of that personally and

-

FA: Right

-

P: And um, and you’re going to be underpaid, and if you’re lucky, you know, you know, you’ll have a living wage at some point

Paul’s theory of the “two types” of youth care workers relies on a hard distinction between those he views as “virtuous people” with “impeccable character” who “want to make a difference” in the lives of children, and those who seek only the material benefits of the job. From his perspective, altruism—a trait that motivates certain people to help others for limited personal gain—is a necessary virtue for long term youth care workers. He figures their work as charitable and holds out as paradigmatic examples a current and former executive director who he believed were motivated by “good Catholic” values.Footnote 7 Of course, the executive directors, however deeply driven they may have been by these values, derived substantially greater material benefits from their work at Promise than did their youth care workers and were not exposed to the same risks and challenges posed by caring directly for emotionally disturbed youth.

Paul and Frank were not alone in identifying altruism as a necessary quality of good (and hopefully long term) youth care workers. In an unprecedented attempt to recruit new youth care workers for all of its programs, a working group of Promise management hired a public relations company to develop a campaign of radio, social media, and print advertisements for a Promise “career fair.” The theme of the career fair, which they hoped would attract dozens of prospective employees, was that youth care workers are “superheroes.” As participants arrived in the Promise gymnasium for the career fair, they were greeted by a team of carefully selected, smiling Promise employees dressed in matching golf shirts, towers of balloons in the organization’s colors, and a life sized cardboard cutout of a superhero dressed in a cape. As attendees passed the registration table, they encountered two 6-foot-tall professionally printed banners. The first showed a preschool aged girl in a mask and red cape with her arm outstretched and her hand in a tight fist. Beside her were listed “Our Values”: “Honesty, Willingness to Learn, Dedication to Purpose, Social Concern, and Self-examination.” The second banner listed statistics about the high poverty rate in the city where Promise is located and concluded with the statement “50%-70% of a child’s behavior is shaped from their environment.” The image of the adorably defiant, caped child beside the agency’s mission and sobering statistics on issues affecting local children seemed designed to spark a sense of altruism on the part of prospective workers. They seemed to say: children at Promise are victims of injustice, and we, the good workers of Promise are here to save the day.

Inside the gymnasium, attendees mingled with Promise employees around standing height tables decorated with balloons. Although only a disappointing 20 job seekers were present, a series of hand-picked youth care workers took the stage in the gymnasium to welcome them and share the video that had been made for the occasion. It featured several youth care workers discussing altruistic reasons for working at Promise: “I get to help kids,” “Make a difference.” The video concluded with each worker affixing a small “superhero” cape around his or her neck and smiling into the camera.

The career fair also included presentations on pay and benefits, Promise’s history and current programs, and short on-the-spot job interviews. The slick, professionally staged event was clearly designed to interpellate individuals who could see themselves in the image of the comic book superhero who, not for material gain, but simply because he or she is Superman or Wonder Woman, comes to the aid of vulnerable people. The chart with figures about childhood poverty framed clients as young victims of an economic system outside their control, while the repetition of the idea that youth care workers are “superheroes” seemed intended to spark the altruistic impulses that management assumed to be inherent in “good” prospective workers.Footnote 8 But it did not work. Frank later reported that, despite the many thousand-dollar price tag of their promotional effort, the event ultimately yielded only one youth care worker.

Youth Care Worker Perspectives on Altruism

Participants in this study espoused a range of beliefs about their motivation for seeking and continuing youth care work. While some of their statements appeared to align closely with executive managers’ descriptions of the ideal altruistic worker, others gave more complicated reports that called into question managers’ assumptions about their motivations and revealed the complexity of their situated moral projects. Midway through fieldwork, I participant observed an optional course in Risking Connection—a training in trauma-informed care that includes curriculum on vicarious trauma (Brown, Baker, and Wilcox 2012; http://www.riskingconnection.com/rc_services.php). Along with ten other participants, I spent 2 days learning from a rotating cast of Promise administrators and members of the “staff development team” in the agency cafeteria. Risking Connection, which was developed in response to a consent decree issued in the state of Maine on behalf of consumers subjected to re-traumatization by service providers, is intended to help workers understand trauma, its symptoms, and its effect on the workforce and to develop empathy and other skills for working compassionately with survivors of trauma. On the final day of training, after watching a heart-rending film about a woman who had experienced a lifetime of traumatic events, youth care workers were asked to list and share with the group responses to the following prompts: “Three signs of vicarious traumatization that you are aware of in yourself; Three ways in which you are positively impacted by the work you do; What benefits do you experience from the work?” On pieces of notebook paper, attendees produced responses that both showed the emotional toll taken by working with Promise clients and perfectly performed for their trainers the kind of altruistic motivation that administrators viewed as characteristic of good workers.

One respondent, who had listed nightmares and hypervigilance as signs that he or she experienced vicarious trauma, also stated: “[I] feel the need to change their lives every day; putting a smile on their faces; them knowing that they can count on me at all times.” Another, who reported feeling “mentally tired” and “thinking people [in life outside of work] are out to sneak something by me,” answered the second question this way: “The feeling you get when a child opens up to you and shares his thoughts; knowing I am making a difference with this type of work; knowing that hopefully one day these kids will look back and see me as a role model.” Another wrote: “This work always allows for meaningful connections and for me to be a change agent; having an impact on a smaller and eventually larger scale.”

Respondents were clear about the difficult emotional toll of youth care work at Promise, and most reported signs of vicarious trauma presented in the training, e.g., nightmares, hypervigilance, emotional exhaustion, and negative beliefs about the world. But, as they were instructed to, they also produced accounts of positive effects the work had on them. These statements resonate with the ideal of the altruistic worker, suggesting that the opportunity to “help” may be rewarding in and of itself and in spite of the effects of what the curriculum termed vicarious trauma. Recurring in these responses are references to facilitating “change,” being viewed as a reliable adult role model, and taking pleasure in “meaningful” interactions with clients. Taken together, they suggest a tenuous balance in youth care work between the high costs of trauma and forms of satisfaction that come from a moral sense of effecting “change” in the present and future. These two-sided responses evoke Hejtmanek’s (2015) workers, who balance their difficult, intimate, and sometimes “disgust[ing]” (105) work with a belief that they are changing the personal and political possibilities of the young men in their care. However, the responses of the Promise workers may also suggest that they were attuned to managers’ belief that good youth care work is driven by altruistic motives and that they produced these altruistic accounts of their work accordingly.Footnote 9

Outside of Risking Connection training, in which managers explicitly evoked narratives of compassion satisfaction, workers’ statements about the rewards of altruism were more often tempered by an acknowledgement of the difficulty and moral complexity of the work. During an interview with Jenny, a youth care worker with three years of experience, two of her clients filled water balloons in the leafy backyard of their cottage. She reported:

-

Jenny: I try to explain to people that the way that I look at it and the way that I have always looked at it is if I can make an impact on one kid out of 500, and I know that I’ve gotten through to one kid, I don’t care if it’s 30 years, 20 years, 5 years, 5 min down the road. And they can be like, like, I know I impacted her at some point. Out of 500 kids, that is a successful day for me

-

First Author: Yeah

-

J: One out of 500 in like a year, that’s still successful for me, and that’s why I come back cause I’m like, “Eh. I can get through [to] one kid. How many kids can I really get through [to]?”

Jenny, who was widely respected by her peers and viewed as a competent youth care worker despite having suffered multiple injuries inflicted by clients and multiple run-ins with the state investigative office, offered a definition of “success” at her job. Imagining an interlocutor who cannot understand why she stays at this job, (“I try to explain to people that the way that I look at it and the way that I have always looked at it…”), she argues that having an “impact” on even “one kid out of 500,” even if that impact cannot be known until the future, allows her to feel that her work has been successful. Knowing that she has been able to help a child in the past seems to challenge her to continue on in her position, to test “How many kids can I really get through to?”

If Jenny is probably hyperbolic in minimizing her effect on the children she works with, Derek, an experienced youth care worker and crisis management team leader, was more expansive about what he saw as the altruistic motivations of good youth care workers. In response to my question, “What makes someone good at this work?” He reported:

-

Derek: And you got to—you got to—a piece of you too has got to kind of have that crusader, that passion that I’m going to change the world, you know, that, you know, the same people that go and, you know, build churches in Africa and stuff

-

First Author: Right

-

D: That’s, that, like, you know, um, that mentality of, you know, I’m not here for a paycheck.

-

FA: Yeah

-

D: I’m here cause my—I want my life to have some meaning

Derek uses images of evangelical Christianity (“crusader[s],” people who “build churches in Africa”) to describe the altruistic orientation of “good” youth care workers. Like Paul, he draws a distinction between those whose work is motivated material gain (“a paycheck”) and those who work with children out of religious-like moral convictions or a desire for “life to have some meaning.” Although Derek does not pursue the analogy in this direction, it is worth noting that youth-care-worker-as-missionary-crusader is apt in at least one other important sense: What they view as good work is not necessarily wanted by its objects, who at times, view them as adversaries and meet them with violent resistance. Indeed, as we have explored previously, youth care work at Promise (and elsewhere) requires workers to engage in a range of practices—including physical restraint of children—that are not desired by clients and do not fit tidily into received understandings of what “helping” children should look like (Hejtmanek 2010, 2015; Smith 2014; Smith et al. 2017). The complex moral projects of “good” youth care workers, then, seem to require both a “passion” to help the other and a stomach for the complexity of what that work actually entails. Later in the same interview, Derek added that youth care workers “are comfortable in chaos and stressed…The kind of people that, um, you know, thrive under pressure or it doesn’t, you know, they don’t—they’re not going to go home and not be able to sleep at night and stuff like that. Um. Nothing—nothing’s on their shoulders…You know, that can—can take some shit, you know?”

Bobby had been a Promise youth care worker for several years, during which time he had been promoted multiple times. He now served as a program supervisor for an off-campus residential program that served as a “step down” for boys leaving higher acuity residential programs. Bobby was an organizational theorist, who obviously spent a great deal of time pondering how he could improve Promise, both for its clients and workers. During more than four hours of interviews, he had much to say on the issue of whether—and how—youth care work should be understood as a moral project. He was particularly keen to what he viewed as a disconnect between management’s belief in the properly altruistic worker and the complex realities facing workers like himself trying to hold together moral projects under the intense demands of their jobs. In particular, he was bothered by the superhero theme of the career fair, which he saw as shifting moral responsibility away from the organization and onto individual workers.

-

Bobby: You can’t just rely solely on the fact that this is good work that you’re doing morally. Morally good work, I mean, which is what they’ve really been pushing lately

-

First Author: Really?

-

B: We had this job fair thing that was all about being a superhero

-

FA: Yeah, I saw that

-

B: And it was ridiculous. It was all about being a superhero. “You have what it takes to be staff,” which is catchy, but there’s no substance behind it, you know? If I’m out looking for a job—when I first came to this job, it wasn’t cause I was called to it. You know, and to a certain extent, you need people here. You’re not going to be able to just appeal to their sense of morality, you know, for why they want to be here. You have to, you know, show them that they can be here and sustain some sort of a lifestyle that you’re okay with

-

FA: So, like to do good and do well at the same time?

-

B: Exactly…and I think, you know, do good and do well enough. Cause like you said, there aren’t people here looking to get rich

-

FA: Right

-

B: It’s not about, you know, having my mansion and my summer home in Lake Placid, you know?

-

FA: Right

-

Bobby: It’s not about that, but we—would people like to be able to afford a home? Absolutely. Would they like to be able to afford to buy a nicer, newer, reliable vehicle? Absolutely. Maybe send their kids to a private school and pay for college? Absolutely. But what are those—where do we see that happening?

Bobby’s critique of the career fair theme is complicated. He does not reject the idea that youth care work is, at least partly, a moral project for some youth care workers or that the icon of the worker as superhero was compelling. He seems to reject the idea that it is only a moral project, and not also a negotiated economic exchange between management and labor. Perhaps reluctantly, he admits that he was not initially “called” to youth care work as a moral project, but as a job. Bobby insists that organizational attempts to fill vacant positions by interpellating altruistic “superheroes” were destined to fail because they did not address the material “substance” of workers’ situations, namely, the fact that their low pay prevented most of them from doing “well enough” to afford a home or to educate their own children. In this way, Bobby masterfully shifts the moral footing of management’s claims about the properly altruistic youth care worker. He not only brings the material conditions of workers’ moral projects back into view, but also launches a moral critique of management. He argues, in essence, that the institution itself was immoral in the heavy burden it placed on the supposed virtue of good youth care workers while neglecting the material needs of this low wage workforce.

Youth Care Work as Moral Project: Jerry’s Vigil

A pair of long interviews with Jerry, a youth care worker with 14 years of experience, provide a useful illustration of the kind of situated moral projects undertaken by Promise workers and the organizational and personal forces that shape those projects. Jerry was an unusual youth care worker in several ways. In his fifties, he was nearly 20 years older than the average youth care worker at Promise. He had a college degree and had previously worked in another profession. Jerry chose to work the overnight shift in a program for adolescent boys with acute mental illness and/or a history of problematic sexual behavior. Dressed in the typical loose, comfortable clothing of youth care workers and a sagging leather bomber jacket, Jerry looked tired, almost sad at the end of his shift. To my surprise, he was eager to talk, and I wondered whether he had been thinking all night of what he wanted to say. His interviews reveal that he viewed his work as a moral project that linked his own past and present through acts of caring for and protecting vulnerable children whose struggles evoked his own early life experiences of abuse and neglect. He portrays himself as doggedly working to keep his clients safe amid organizational conditions that he believed sometimes threatened that goal.

Jerry explained that he had first applied for overnight work at Promise after a stressful period in his life. Like Bobby, his initial motivations were practical rather than altruistic. He had imagined that the overnight job would be “easy work” and allow him time to think, pray, and meditate. At times it had, even though at other times the job had exposed him to extreme stressors, including client violence and the possibly stress-related death of a much-respected supervisor. If he had started out as a youth care worker as a way to turn inward, he eventually came to see his work as deeply relational and essential to the functioning of the program, even if the value of his work was not always apparent to supervisors and coworkers on the day shift. He explained that his late supervisor had often encouraged him to move to daytime work:

-

Jerry: He goes, “Well, you know, you know, eventually you’re going to want to get off of the overnight.” And I said, “Well, why?” And he said, “Well, you know, to better yourself.” And I said…

-

First Author: Whoa

-

J: I said, “Would I get paid more for working during the day?” And he goes, “No.” And I said, “Well, then, why would I want to work during the day?”

-

FA: Wow

-

J: And I—and there were times when I did think about it. I thought, you know, “Maybe I can have a more positive impact. I’d be able to do better with the kids if I worked during the day.” And—but it usually wouldn’t take me very long to talk myself out of that. Um, I like the quietness of the night

-

FA: Yeah

-

J: Um, I like to be able to read. Um, and I felt like although I think that the staff and the supervisors oftentimes undervalued what I did, I also knew that if I didn’t do what it was that I was supposed to do that the entire cottage would go into turmoil

Here Jerry seems to reject altruistic motives for switching to the less “quiet” day shift (“would I get paid more?”) Although his superiors, as Jerry himself once had, sometimes assumed that the overnight shift was “easy” work that didn’t allow for Jerry to make much of a “positive impact” on clients, he came to understand his nighttime work as an important moral project even if it was “undervalued” by others. When I asked Jerry to describe the tasks of his job he explained that he arrived as clients were settling into their beds for the night. He was also responsible for waking clients in the morning and helping them accomplish their deceptively simple morning routines, which included toileting, showering, dressing, eating, and packing materials for the school day. In between, Jerry was often the only adult supervising six to ten boys, whose psychiatric and behavioral needs had been deemed too acute for home or foster care placement. This meant that he worked with boys with enuresis who hid their urine-soaked sheets anywhere they could or whose compulsive sexual behavior kept them awake much of the night. He had to break up fights, monitor program spaces for objects that could be used as weapons, and see that clients with histories of sexually abusing others did not enter the rooms of their peers. He carried a police-style two-way radio with which he could call for assistance from other workers if a “crisis” outstripped his ability to manage it. Sometimes they had. Once, a coworker of Jerry’s had been “jumped” by a group of clients as he attempted to physically restrain one of them. Boys beat him with objects they had placed in a sock.

Jerry also had to negotiate what he viewed as impossible conflicting organizational demands. For example, he was for a period of time expected to go downstairs at night to wash towels. This required him to leave the second floor where he was also expected to supervise his sleeping charges at all times. He said, “We had kids who I knew that if given the opportunity would do something sexual with the other and I knew I would also get in a great deal of trouble if I wasn’t checking on them or even there.” He complained to his supervisors about this double bind until they finally relieved him of his laundry duties. He also reported repeatedly spending his limited social capital with supervisors advocating for a client with enuresis to get a clean, plastic-covered mattress or for “pet rocks” to be removed from the room of a client who had a history of violence against peers and workers.

As our interviews went on, a theme reappeared: Jerry understood his work as deeply moral. It was his job to notice his clients’ needs—like a new mattress, or a more flexible bedtime—and advocate on their behalf for adequate treatment. Despite their troubling behavior, he viewed them as children who needed something akin to attentive and protective parenting. It was his job to keep watch over these troubled, dangerous, and frightened boys and to keep them safe until morning. Jerry described working with a boy who had come to his program after being sexually assaulted by several young men in his neighborhood. Among many other symptoms of trauma, he had difficulty sleeping through the night.

-

Jerry: I remember one kid. I had done two restraints with him, and he’d never directed his aggression at me. He was a little guy and had been transferred from another cottage. And um, he was—in his community, he was gang raped by a bunch of older boys

-

First Author: Oh, jeez

-

J: And so, he was the youngest boy in our cottage, and he was very small. And they told me, “Oh, he’s going to be a handful.” And he wakes up at four o’clock in the morning and he starts crises. He stabbed a staff with a pencil. Um, he was the one that they said…shouldn’t belong here. And um, within a short period, like, he slept later because they didn’t let him go to bed at six o’clock in the morn—at night. So he’d actually sleep for a good portion of the night, but then he’d wake up. And I notice he did something really—he would do something in the middle of the night. He’d, like, around five o’clock, he’d wake up. And then I’d hear real quiet. He’d say, “Staff.” And I’d go over to his door and I’d say, “Yeah? Do you need anything?” He’s like, “Never mind.” Cause it was quiet. He was checking to see if I was awake. And that’s why, I think, he wasn’t aggressive towards me. Uh, and you know, [former supervisor’s] advice of, you know, build relationships with the kids. That’s going to go a long way. If they know that you care about them it’s going to make your job easier and everything better. And so, I—I know that the kids, um, I’d say many of the kids know that I care about them. Uh, and if they don’t know when they first get there, they kind of see it after a little bit. And I mean, like, I pray a lot, and I try to kind of emanate loving, positive, safe energy.

In Jerry’s narrative, although he has had to physically restrain the client multiple times, he is able to view this problematic “little guy” primarily as a victim of shocking trauma, rather than as a violent aggressor. He interprets the child’s calls to him in the middle of the night as a way of checking to see that Jerry was indeed watching over him as he tried to sleep, and he believes that these tender exchanges helped him build a positive therapeutic rapport with him. Although he characterizes strong “relationships” with clients as instrumental (i.e., “it’s going to make your job easier”), he seems also to sincerely experience caring feelings for them—feelings whose origins became clearer as we continued to talk.

In our second interview, he recounted a poignant narrative that linked the contemporary moral project of his youth care work with his own troubled past. He initially discussed his low pay and the physical and emotional threats posed by the work, but he quickly began, through a series of remembered conversations with others, to tell a story about his own childhood and its relationship to his current work:

-

J: I’m hearing sometimes even $15 an hour, and I think to myself, “Wow. Fourteen and a half years experience is only worth $2.” And—and that is why people become dissatisfied. And then, on top of not only that, but also feeling, uh, feeling unsafe. I—actually I remember talking and then I had a conversation with one of the [Promise] social workers one time, and I had mentioned that my childhood was a little crazy. That, um, I had witnessed a lot of violence in my home, a lot of drugs, and substance abuse and alcohol. And I told her. I told—I had mentioned to my one friend one time, I said that I used to sleep with my window cracked because my dad, um, had threatened to kill me and my mom. And so, I—I had this window and it slid sideways and it’d lock, but I would crack it just enough so I could actually hit it without it actually stopping. It was right next to my bed, and there was no screen. So I could actually jump out that window. Um, because the thought was when I’d go to bed is that if I hear a gunshot in the middle of the night, I need to get out that window.

-

FA: Oh my gosh.

-

J: And away. Uh, before he got to my room. And my one friend said, he goes, “Well,” he said, “That’s really messed up.” He goes, “You probably have post traumatic stress disorder.” And I say, “You know, you might be right.” And then, in learning here where I’ve taken classes about how your brain chemistry changes [as a result of traumatic experiences].

-

FA: Yeah.

-

J: And I had mentioned to the—the social worker some of these things. And I said, “You know,” I said, “I’ve never—I normally would stay awake almost all night. So it’s almost like abnormal for me

-

FA: Yeah.

-

J: To, like, it’s not abnormal for me to stay awake very late. If I had no restrictions on when I could go to sleep, I would probably stay up ‘til about 4 or 5 in the morning every day and then go to sleep.” And she said—she goes, “That is probably why you work the overnight because bad things happen at night.”

-

FA: And so, your job is to watch over these kids and make sure they’re safe until they wake up in the morning.

-

J: Yeah. Sorry I’m… [begins to weep]

-

FA: It’s okay. I’m crying too.

-

J: When I’m—when I’m tired, I actually have a hard time containing, like, cause sometimes if I talk to my wife

-

FA: Yeah.

-

J: In the morning, I’ll start. I’m not crying yet right now, so, um, but she said—she goes—she goes, “That’s probably why you work the overnight.” She goes, “Because bad things happen at night.” She goes, “And it’s your job to stay alert.”

-

FA: Right.

-

J: “To be able to respond to an emergency.” And I don’t think I really connected that that’s why I stay here, but I thought, “That makes a lot of sense.”

Jerry’s account of linking his childhood experiences to his desire to work the night shift at Promise is a moral narrative on multiple levels because it positions him as endeavoring to be a “good” worker within the constraints and opportunities presented by the organizational setting and his own personal history. On one level, his narrative exemplifies a way of talking about altruism that was common in interviews with Promise workers: They framed youth care work as a way to “give back” or “pay it forward” after difficult experiences in their own childhoods. On another level, it shows Jerry trying to make sense of his work, to understand why he stays in a low-wage job in which his 14 years of experience have afforded him only a $2 an hour pay raise. It is perhaps not coincidental that his emotional retelling of the connection between his work and childhood follows his complaint about his hourly wage. In this way, he identifies his own very personal brand of altruism as a reason why he continues to work for wages he finds unfair. Another way to read Jerry’s account is that he is able to draw on his own experiences to generate empathy for his troubled clients, who require patience and tolerance and sometimes offer barely perceptible rewards in the form of functional therapeutic relationships. This empathy may be evidenced by his tears in retelling the story of how he came to see that he was watching over children as he wished someone had watched over him.

In particular, by offering this story of his own suffering in the care of abusive adults, Jerry strongly suggests that his tolerance for the disturbing, difficult behavior of children (and perhaps also of management) is motivated by empathy. He has been the fearful child at the mercy of powerful and unpredictable adults, and frames his work as attempts to respond to such a subjectivity. Although Jerry does not call it “love” in this account—a construct that was rarely evoked at Promise—it resonates with Hejtmanek’s (2015) account of “mad love” as a driver of care, an active ingredient in healing, and a counterbalance to the difficulties of the work.

But still, Jerry was contemplating quitting. He had been injured on the job and many of his organizational suggestions had been ignored. He had seen others injured, fired, or unjustly prosecuted for child abuse. He knew he could make more money elsewhere. His was a complicated project of being a “good” youth care worker in a nearly impossible context. To be good, he believed he must frequently challenge his superiors; he must wait out incompetent bosses and staff shortages; he must give up his daytimes to sleep so that he can work when the children are less likely to be violent and more likely to need the quiet protection that he sees himself as especially prepared to offer. It was a tensely balanced moral project for Jerry that was charged with emotion and woven into his own autobiography. And yet, some of his supervisors had cast Jerry as a troublemaker who made too many appeals to management on behalf of both clients and other workers. For all of his apparent moral striving, some managers took his advocacy as a sign that he was, in fact, in it for the “wrong reasons.”

“Cultural Noise” and the Silence of Altruism: Institutional Critique as a Sign of Moral Failing

As both Jerry’s and Bobby’s interviews suggest, some Promise managers tended to view youth care workers’ legitimate requests for organizational change—such as Jerry’s laundry double bind or Bobby’s demands for better pay for new hires—as evidence of individual failings rather than as legitimate institutional critique. In particular, managers sometimes framed such critique as a failure of proper altruistic motivation, shifting blame from organizational practices to supposedly inherent traits of individual workers. In the summer of 2016, Paul—the administrator who theorized “two kinds” of youth care workers— had led a major initiative to improve landscaping at Promise. Contractors removed yew bushes grizzled by dozens of snowy winters and replaced them with rounded planting beds dotted with young shrubs and blooming perennials. The new landscapes were an aesthetic improvement over the threadbare sod and dying bushes, but, according to some youth care workers, there was a major problem—one that keenly showcased what they viewed as a “disconnect” between management and youth care workers: The lovely new landscapes included mounds of smooth, softball-sized stones that they instantly recognized as potential projectiles.

To youth care workers trained to search program spaces for anything that a client might use as a weapon—from “pet rocks,” to scissors, to knitting needles, to nail polish remover—that managers had approved a landscape plan that included dozens of potential weapons was taken as evidence that they either (1) did not understand workers’ job tasks and the acuity of clients, or (2) did not care about the safety of clients or workers. Bobby put it this way in an interview: “The messaging that came out from all this fucking landscaping is we care more about our facilities and our grounds…than we do about our staff. And that’s—that’s been an overwhelming sentiment of all of the staff that I’ve seen walking around campus just going, ‘what the hell are we doing? What are we doing?’ I got no idea. I’m sorry.”

I interviewed Paul just after the stones had been installed. When I pressed him to explain how he differentiated between “virtuous,” altruistic workers and those who sought only material rewards, he cited recent complaints about the landscaping stones as an example of the latter:

-

Paul: I see a lot of folks that are in the audience of commentary that aren’t necessarily people that are going to contribute to the long-term of this work.

-

First Author: Okay.

-

P: I call them—I’m going to call that cultural noise.

-

FA: Okay.

-

P: Okay? So I think it’s hard to pick apart. It’s like the discussion on the stones. Is that really meaningful or is it just the cultural noise because of something else? Some tension, some difficulty, something. Some—maybe they don’t want to do this work. Okay?

-

FA: So you could come in here—if you weren’t familiar with this organization…

-

P: That’s correct.

-

FA: You could come in here and listen to whoever.

-

P: Yes.

-

FA: Complaining, like, “Oh my God. I can’t believe they put these stones cause some kids are going to throw them at me.”

-

P: Yeah.

-

FA: “This—it’s just like this place. That’s ridiculous.”

-

P: Yeah. Yeah.

-

FA: If you didn’t know that that was, for lack of a better term, kind of a script that people engage in…

-

P: Yeah. Yeah.

-

FA: For other reasons, you would misinterpret that.

-

P: Could.

-

FA: Yeah.

-

P: Yeah. And so, for those people that want, that are ambitious. And that want to excel and exceed and, um, they want to, and you know, peddle influence…

-

FA: Mm hmm.

-

P: You know, if you listen to a lot of that, you begin working on those things… You listen to the noise and you begin, “All right. We’re not going to have stones…”

-

FA: Right.

-

P: “Anywhere else on this campus. We’re going to take all the stones away and we’re going to put in something else” and what did that do for us?

-

FA: Yeah.

-

P: Um, I don’t know, but the cultural noise would say it’s a better place. I’m not so sure that we are. I think that—I hope you’ve, that was just a, all right. Let me—let’s keep going. I’m not going to…

-

FA: You go wherever you want.

Although later in the interview Paul softened his stance toward those who objected to the stones, saying, “I think it could be [they’re] frustrated for good reasons,” he clearly argues that complaints of this type should be taken as evidence (even, or especially by an unfamiliar outsider) that the organizational critic is of the unvirtuous type of youth care worker. He further designates such critique as “cultural noise”: a distraction that is “not meaningful” except as an expression of the worker’s own “difficult[ies].” He contrasts cultural noise makers with “ambitious” workers who want to “excel” and “peddle influence,” and explains that these virtuous workers (and perhaps administrators) might be taken in by such misguided complaints and remove the stones from the facility. He is incredulous that this action would improve conditions at Promise, though he does not specify why before changing the subject.

Paul’s theory of two types of youth care workers divides them neatly into virtuous altruists and unvirtuous, complaining, instrumental wage earners. According to Paul, voicing even reasonableFootnote 10 critiques of organizational decisions evidenced a failure or lack of altruism on the part of workers. It not only betrayed the speaker’s identity as an unvirtuous worker, it also threatened to distract or misguide those who he believed were properly altruistic. In Paul’s theory, then, properly altruistic workers should stay silent on organizational matters, even, as they did in the case of the stones, when they posed a possible threat to safety. His theory of “cultural noise,” then, serves to disempower institutional critique by workers and discredit—on a moral level—those who engage in it.

Conclusions and Implications

Youth care workers and managers at Promise, in differing ways, understood youth care work as moral. Following in the U.S. tradition of viewing child care as sentimental and incommensurate with labor relationships (Hardesty 2018), managers insisted that good youth care workers were motivated by an innate altruistic impulse that drove them to work with vulnerable youth and sustained them even under challenging working conditions. Although they acknowledged the difficulty of youth care work at Promise, characterized by low pay, undesirable hours, and exposure to client violence and intense legal scrutiny by the state regulatory agency, they believed that properly altruistic workers would seek and continue in their positions out of a “virtuous” desire to help vulnerable children. Their recruitment efforts were designed to interpellate such individuals and relied on this theory of youth care workers to address the organization’s serious problem with worker turnover. In at least Paul’s case, the belief in the youth-care-worker-as-altruist could be used to do more than valorize the moral character of certain workers or attract promising prospective employees: It could be used to deflect critiques of the institutional practices. If questioning the decisions of management was evidence that the worker was of poor moral character (i.e., not altruistic, in it “for the wrong reasons”), then such critiques could be justifiably ignored. Although Paul’s example of the landscape stones involves a critique of safety practices, his logic could just as easily be used to deflect workers’ claims for better wages, hours, or benefits. To ask for a raise, of course, would be to acknowledge that one was not satisfied with the moral rewards of their ostensibly altruistic work.

Youth care workers themselves described a very different moral ordinary, which challenged managers’ assumptions that good youth care work should be primarily, if not exclusively, motivated by altruism. In the context of a training led by administrators, on command, workers produced statements about their altruistic motives and the moral rewards of their work, even as they obediently catalogued signs that they also experienced negative consequences of their work. They appeared aware that the preferred narratives of management were those that performed altruistic motivation and the moral satisfaction thought to come with it. But in confidential interviews, they described far more complex moral projects in which altruism was only one component. Even though most acknowledged a desire to help and care for their clients for their own sake, they consistently placed these moral narratives alongside practical, material concerns. Bobby initially came “looking for a job,” not because he was morally “called” to the work and railed against managers’ appeals to altruism in their ill-fated hiring campaign. Jerry, who wept as he recounted watching over a traumatized client as he slept, was not tempted to move to the day shift in part because it didn’t involve a pay raise commensurate with what he saw as greater demands. Even Derek, who framed youth care work as a “crusade” and a “passion…to change the world” had to admit that this was only a “piece” of the work they did.

Youth care workers in this study seemed to understand their work as a moral project in much the same way that Mattingly (2013, 2014) has framed the term. While managers viewed altruism as an intrinsic quality of good workers—something one does or does not possess—workers were acutely aware that doing good and being viewed as good in this site of practice required a difficult, ongoing engagement with the world as they found it at Promise and with their own skills, life histories, and limited available moral scripts.

The difference between these views bears a family resemblance to Carr’s (2006, 2011) work on what she has termed the ideology of inner reference—a language ideology that views healthy talk as transparent expressions of presumed inner properties. Like her drug treatment counselors who demanded that clients produce “open” and “honest” talk (2011:13), Promise managers insisted that moral qualities were innate and more or less virtuously expressed in language and action. Carr’s clients, whose health and virtue were evaluated by their speech, learned to dutifully produce linguistic performances in line with this ideology. At Promise, too, youth care workers demonstrated their ability to produce altruistic scripts at the request of their superiors. But, like Carr’s clients, they understood themselves to be engaged in far more complex moral projects. And, as Carr demonstrates so powerfully, the belief in inner referents and their “clean” expression, allowed more powerful actors—in her case counselors, and in this case, managers—to cast legitimate institutional critique as evidence of moral failing.

The moral discourse presented here also resonates with Brodwin’s approach to the study of “everyday ethics” (2013, 2014). His community mental health workers must translate abstract ethical principles into situated metal health practice through complex negotiations between team members, organizational mandates, and recipients of services. Like Mattingly’s informants, Brodwin’s cannot retreat to abstract, preformed concepts of the good; they must hash it out with whatever implements they can access. We argue here that youth care workers at promise—the lowest paid, and least educated providers of mental health care for institutionalized children—engaged in similarly sophisticated and difficult moral work.