Abstract

This article profiles visual auras among traumatized Cambodian refugees attending a psychiatric clinic. Thirty-six percent (54/150) had experienced an aura in the previous 4 weeks, almost always phosphenes (48% [26/54]) or a scintillating scotoma (74% [40/54]). Aura and PTSD were highly associated: patients with visual aura in the last month had greater PTSD severity, 3.6 (SD = 1.8) versus 1.9 (SD = 1.6), t = 10.2 (df = 85), p < 0.001, and patients with PTSD had a higher rate of visual aura in the last month, 69% (22/32) versus 13% (7/55), odds ratio 15.1 (5.1–44.9), p < 0.001. Patients often had a visual aura triggered by rising up to the upright from a lying or sitting position, i.e., orthostasis, with the most common sequence being an aura triggered upon orthostasis during a migraine, experienced by 60% of those with aura. The visual aura was often catastrophically interpreted: as the dangerous assault of a supernatural being, most commonly the ghost of someone who died in the Pol Pot period. Aura often triggered flashback. Illustrative cases are provided. The article suggests the existence of local biocultural ontologies of trauma as evinced by the centrality of visual auras among Cambodian refugees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Only about 1% of the population have experienced an aura never associated with migraine (Kunkel 2005).

These may be compared to corruscations on a rippling surface.

The term scintillating refers to a shimmering or flashing, and scotoma to a zone of loss of vision such as where the bright crescent of the scintillating scotoma blocks vision or where an area of darkness or pure absence of vision occurs.

The crescent may also be said to be like roiling water or like a heat mirage.

There are variations of the scintillating scotoma such as it lacking the inner darkness (i.e., the negative scotoma), as its bright zone being less C-shaped and rather straighter, or its crescent springing fully formed into the visual field.

The descriptor “fortification spectrum” evokes the image of the triangle-shaped ramparts of a fort.

Other authors have excluded general blurry vision as being a visual aura (Queiroz et al. 2011). Patients were not asked about areas of visual loss but if patients mentioned them then these they were counted.

From the Mayo Clinic, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AVYjbthGk2s.

To further describe the flashing of phosphenes and scintillating scotomas, patients sometimes used either the term phleut phleik or prieuk prieuk. Both of these reduplicatives richly evoke through sound symbolism the idea of light being repeatedly emitted. To emphasize the sense of emission of light while saying these reduplicates, patients often opened and closed the hand, the hand motion suggesting a pulsating light like that of a firefly.

Fireflies most closely resemble phosphenes but patients also described the scintillating nature of the crescent-shaped scotomas with that phrase.

Some patients experienced a kind of undulation of vision like rippling water hit by light, coruscations. The undulation might be compared to a heat mirage. To depict the undulating-like quality of the bright part of a scintillating scotoma, some patients used the term “heat mirage” (tngay beundaeu goun, or literally, “the sun walks her child”), a term that is normally used to refer to the undulating-like appearance of heat rising from a hot surface; in the extreme heat of Cambodia, such heat mirages are commonly seen.

Some patients had a negative scotoma that either stayed one size or grew larger but lacked a bright or colored crescent.

There are approximately 300 patients at the clinic, so that in some cases a patient would have been involved in more then one survey. The surveys were conducted over a period of a year and were not overlapping.

These triggers were investigated based on previous ethnography.

Patients usually refer to dysphoric thinking as “thinking a lot.” “Thinking a lot,” or kut caraeun, is a phrase that in Cambodian refers to having dysphoric cognitions such as worry (e.g., about paying the rent) and depressive thoughts (about deceased relatives). On “thinking a lot” among Cambodian populations, see Hinton, Reis, and de Jong (2016).

As indicated above, the literature indicates that aura usually follows migraine whereas our clinical experience with Cambodians indicated the opposite.

One migraine criteria was not used, namely, lasting over 4 h if not treated, because it is difficult for patients to assess how long an untreated headache episode would last since they usually treated the episodes in some way.

Usually the orthostasis that caused aura was standing up from a lying down position or from a sitting position but sometimes the orthostasis that caused aura was one of the following: sitting up from a lying position, standing up from a squatting position, or straightening up after bending down to pick up something.

In the other 30% of cases, the migraine occurred out of the blue or owing to some cause such as awakening from a nightmare.

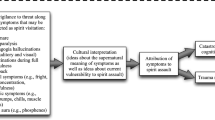

Patients often indicated the belief that the aura on its own had the power to initiate symptoms, especially dizziness, but also discussed how auras gave rise to catastrophic cognitions and trauma recall (see the following studies) that resulted in fear and multiple symptoms.

If dysphoric thinking is present with aura then fear of khyâl attack is also great because “thinking a lot” is considered a cause of a khyâl attack. In fact, dysphoric thinking is often present in the aura sequence because dysphoric thinking often initiates the aura firing sequence (see Study IV), for example, causing a migraine headache that leads to an aura.

Many patients were initially reluctant to relate to the clinician (the first author) or family members that they had experienced an aura they considered to be a ghost. When patients did initially describe the auras that they considered to be a ghost, many patients look terrified, and often described having goose bumps out of fright. Some had the sense that the ghost had come near to them upon their talking about the ghost; in fact, goose bumps are considered a sign that a ghost is near. The hesitancy to recount having an aura that was thought to be a ghost, and great fear on doing so, were the following: if one admits to being afraid of a ghost, the ghost will attack more ferociously; if one talks about ghosts they will attack more often because just conjuring to mind the spirit is a sort of summoning; if one tells someone about a ghost attack, that person may be attacked; and if one talks about ghost attacks, one may be considered crazy.

Patients were asked about episodes in the last week to assure accuracy of recall.

For a detailed description of what Cambodians do to treat “thinking too much,” see Hinton, Reis, and de Jong (2016).

In the Cambodian Buddhist calendar, there is a special day that is devoted to making merit for the dead, called peucheum bon, on which one presents offerings at the temple to the monks, after which the monk burns a piece of paper on which is written the names of the persons for whom one is making merit. The Cambodian New Year holiday is another occasion during which much merit making is made for the deceased in these same ways.

Frequently the patient had not only auras attributed to ghost attack but also events considered a spirit visitation: seeing visual hallucination during sleep paralysis (seeing a shape descend on the body) and heard themselves called out to at other times such as upon awakening or falling asleep.

One of the most powerful such strings comes from the sacralization of a new temple, a ceremony called poeut seuymaa, “surrounding the sacred center.” Strings are strung around the perimeter of the temple, and then many monks, holding these strings, chant to “secure the perimeter,” creating a sacred boundary that prevents any demons from entering in. Also, specially blessed metal balls and other special objects are placed in holes dug around the perimeter in the ceremony. These long strings are considered very sacred, and are cut into small lengths to make sacred bracelets.

Sometimes the monk makes the holy water; to do so, monks chant while a candle burns, the candle having been set on the rim of the basin that holds the water that is being blessed.

All former soldiers were usually arrested and killed.

The Khmer Rouge commonly used this term in condemnation.

Likewise, Cambodians have a specific term for sleep paralysis, namely, "the ghost pushes you down” (khmaoch sangât), with sleep paralysis being a generally known phenomenon that is commonly experienced (Hinton et al. 2005), whereas the general English-speaking population in the United States has no term for sleep paralysis, which is a minimally recognized phenomenon that is rarely experienced (on cultural kindling, see Cassaniti and Luhrmann 2014).

Other studies have found a lower rate of the visual aura being colors other than black and white (Queiroz et al. 2011).

The migraine literature often describes the aura as consisting of a cross-hatching of white and black lines but this was rarely observed in the current study. Rather, it was found that the aura had many colors that formed flame-like shapes, similar to what is depicted in the Mayo Clinic video. In fact, the term “fortification spectra” would seem a less apt description than “flaming spectra” for what is experienced by Cambodian refugees.

Various triggers of aura and of migraine have been noted in the literature such as stress, temperature shifts, bright lights, and sinus congestion (Peris et al. 2017).

In that study, among those with migraine, 40/59 complained of vertigo on postural shift compared to 4/49 in the control group (OR = 23.7, CI 7.4–75.5, p < 0.001), and among those with migraine, 30/59 complained of scintillating scotoma induced by postural shift as compared to 1/49 in the control group (OR = 49.6, CI 6.4–383, p < 0.001).

In fact, there is a large literature indicating that migraine predisposes to dizziness on standing up (Chelimsky et al. 2009; Curfman et al. 2012; Drummond 1982; Neuhauser and Lempert 2004; Peroutka 2004a, 2004b; Raskin and Knittle 1976): one study in India found that 54% of those with migraine complained of having near syncope upon standing up during episodes of migraine (Gupta and Bhatia 2011). This orthostatic dyseguluation may be a cause of visual aura on standing up. Cambodians have multiple reasons for orthostatic dysregulation other than migraine, and in fact have been shown to have an abnormal orthostatic blood pressure response when distressed (Hinton et al. 2010). In the current study, orthostasis-caused aura was sometimes preceded by dysphoric cognizing, and the literature indicates that acute anxiety may lead to orthostatic dysregulation through various means that include decreased vagal tone and vestibular effects (Hinton et al. 2010). Yet still, the patients in this study with aura had elevated rates and severity of PTSD, and PTSD predisposes to orthostatic dysregulation. And finally there is evidence that certain Asian groups may be predisposed to orthostatic dysregulation (Hinton et al. 2010).

There is also the concept of structural violence, the converging of socio-cultural forces, particularly socio-economic ones, to create disorder (Farmer 1997). Anthropology has recently put more emphasis on comorbid disorders, the concept of syndemics, a kind of synergy of “epidemics” in which the interaction of certain disorders is investigated and how that interaction creates a multiplicative rather than an additive effect (Mendenhall 2016; Singer and Clair 2003).

For example, migraine rates are linked not only to psychiatric disorders as reviewed above but also to low socio-economic status, which is a key indicator of exposure to stressors (Peterlin and Scher 2013).

References

Becker, Elizabeth 1998 When the War Was Over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge Revolution. New York: Public Affairs.

Berger, M., R.P. Juster, and Z. Sarnyai 2015 Mental Health Consequences of Stress and Trauma: Allostatic Load Markers for Practice and Policy with a Focus on Indigenous Health. Australasian Psychiatry 23(6):644–649.

Borsook, D., N. Maleki, L. Becerra, and B. McEwen 2012 Understanding Migraine through the Lens of Maladaptive Stress Responses: A Model Disease of Allostatic Load. Neuron 73(2):219–234.

Cassaniti, J.L., and T.M. Luhrmann 2014 The Cultural Kindling of Spiritual Experiences. Current Anthropology 55:S333–S343.

Chandler, David P. 1991 The Land and People of Cambodia. New York: Lippincott.

Charles, A., and J.M. Hansen 2015 Migraine Aura: New Ideas About Cause, Classification, and Clinical Significance. Current Opinion Neurology 28(3):255–260.

Chelimsky, G., S. Madan, A. Alshekhlee, E. Heller, K. McNeeley, and T. Chelimsky 2009 A Comparison of Dysautonomias Comorbid with Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome and with Migraine. Gastroenterology Research Practice 2009:701019.

Curfman, D., M. Chilungu, R.B. Daroff, A. Alshekhlee, G. Chelimsky, and T.C. Chelimsky 2012 Syncopal Migraine. Clinical Autonomic Research 22(1):17–23.

Dahlem, M.A., and N. Hadjikhani 2009 Migraine Aura: Retracting Particle-Like Waves in Weakly Susceptible Cortex. PLoS ONE 4(4):e5007.

de Jong, J.T., and R. Reis 2010 Kiyang-Yang, a West-African Postwar Idiom of Distress. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 34:301–321.

de Jong, J.T., and R. Reis 2013 Collective Trauma Resolution: Dissociation as a Way of Processing Post-War Traumatic Stress in Guinea Bissau. Transcultural Psychiatry 50:644–661.

DeLange, J.M., and F.M. Cutrer 2014 Our Evolving Understanding of Migraine with Aura. Current Pain Headache Reports 18(10):453.

Drummond, P.D. 1982 Relationships among Migrainous, Vascular and Orthostatic Symptoms. Cephalalgia 2(3):157–162.

Ertas, M., B. Baykan, E.K. Orhan, M. Zarifoglu, N. Karli, S. Saip, A.E. Onal, and A. Siva 2012 One-Year Prevalence and the Impact of Migraine and Tension-Type Headache in Turkey: A Nationwide Home-Based Study in Adults. Journal of Headache Pain 13(2):147–157.

Farmer, P. 1997 On Suffering and Structural Violence: A View from Below. In Social Suffering. A. Kleinman, V. Das, and M. Lock, eds., pp. 261–284. Berkeley: University of California.

Gupta, R., and M.S. Bhatia 2011 Comparison of Clinical Characteristics of Migraine and Tension Type Headache. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 53(2):134–139.

Gustafsson, Mai Lan 2009 War and Shadows: The Haunting of Vietnam. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Hinton, D.E., P. Ba, S. Peou, and K. Um 2000 Panic Disorder among Cambodian Refugees Attending a Psychiatric Clinic: Prevalence and Subtypes. General Hospital Psychiatry 22:437–444.

Hinton, D.E., and B.J. Good 2016a The Culturally Sensitive Assessment of Trauma: Eleven Analytic Perspectives, a Typology of Errors, and the Multiplex Models of Distress Generation. In Culture and PTSD: Trauma in Historical and Global Perspective. D.E. Hinton, and B.J. Good, eds., pp. 50–113. Pennsylvenia: University of Pennsylvenia Press.

Hinton, D.E., and B.J. Good, eds. 2016b Culture and PTSD: Trauma in Historical and Global Perspective. Pennsylvenia: University of Pennsylvenia Press.

Hinton, D.E., A. Hinton, D. Chhean, V. Pich, J.R. Loeum, and M.H. Pollack 2009a Nightmares among Cambodian Refugees: The Breaching of Concentric Ontological Security. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 33:219–265.

Hinton, D.E., A.L. Hinton, K.-T. Eng, and S. Choung 2012 PTSD and Key Somatic Complaints and Cultural Syndromes among Rural Cambodians: The Results of a Needs Assessment Survey. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 29:147–154.

Hinton, D.E., S.G. Hofmann, S.P. Orr, R.K. Pitman, M.H. Pollack, and N. Pole 2010 A Psychobiocultural Model of Orthostatic Panic among Cambodian Refugees: Flashbacks, Catastrophic Cognitions, and Reduced Orthostatic Blood-Pressure Response. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2:63–70.

Hinton, D.E., A. Nickerson, and R.A. Bryant 2011 Worry, Worry Attacks, and PTSD among Cambodian Refugees: A Path Analysis Investigation. Social Science and Medicine 72:1817–1825.

Hinton, D.E., S. Peou, S. Joshi, A. Nickerson, and N. Simon 2013 Normal Grief and Complicated Bereavement among Traumatized Cambodian Refugees: Cultural Context and the Central Role of Dreams of the Deceased. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 37:427–464.

Hinton, D.E., V. Pich, D. Chhean, and M.H. Pollack 2005 “The Ghost Pushes You Down”: Sleep Paralysis-Type Panic Attacks in a Khmer Refugee Population. Transcultural Psychiatry 42:46–78.

Hinton, D.E., A. Rasmussen, L. Nou, M.H. Pollack, and M.J. Good 2009b Anger, PTSD, and the Nuclear Family: A Study of Cambodian Refugees. Social Science and Medicine 69:1387–1394.

Hinton, D.E., R. Reis, and J.T. de Jong 2016 A Transcultural Model of the Centrality of “Thinking a Lot” in Psychopathologies across the Globe and the Process of Localization: A Cambodian Refugee Example. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 40:570–619.

Juang, K.D., and C.Y. Yang 2014 Psychiatric Comorbidity of Chronic Daily Headache: Focus on Traumatic Experiences in Childhood, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Suicidality. Current Pain Headache Reports 18(4):405.

Kunkel, R.S. 2005 Migraine Aura without Headache: Benign, but a Diagnosis of Exclusion. Cleveland Clinical Journal of Medicine 72(6):529–534.

Kwon, H. 2008 Ghosts of War in Vietnam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lipton, R.B., M.E. Bigal, M. Diamond, F. Freitag, M.L. Reed, W.F. Stewart, and Ampp Advisory Group 2007 Migraine Prevalence, Disease Burden, and the Need for Preventive Therapy. Neurology 68(5):343–349.

Luhrmann, T.M. 2013 Making God Real and Making God Good: Some Mechanisms through Which Prayer May Contribute to Healing. Transcultural Psychiatry 50:707–725.

Maleki, N., L. Becerra, and D. Borsook 2012 Migraine: Maladaptive Brain Responses to Stress. Headache 52(Suppl 2):102–106.

Marshall, G.N., T.L. Schell, M.N. Elliott, S.M. Berthold, and C.A. Chun 2005 Mental Health of Cambodian Refugees 2 Decades after Resettlement in the United States. JAMA 294:571–579.

Marshall, G.N., T.L. Schell, E.C. Wong, S.M. Berthold, K. Hambarsoomian, M.N. Elliott, B.H. Bardenheier, and E.W. Gregg 2016 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Cambodian Refugees. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 18(1):110–117.

McDonald, S.D., and P.S. Calhoun 2010 The Diagnostic Accuracy of the PTSD Checklist: A Critical Review. Clinical Psychology Review 30:976–987.

McEwen, B.S. 2007 Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain. Physiological Reviews 87(3):873–904.

Mendenhall, E. 2016 Beyond Comorbidity: A Critical Perspective of Syndemic Depression and Diabetes in Cross-Cultural Contexts. Medical Anthropological Quarterly 30:462–478.

Minen, M.T., O. Begasse De Dhaem, A. Kroon Van Diest, S. Powers, T.J. Schwedt, R. Lipton, and D. Silbersweig 2016 Migraine and Its Psychiatric Comorbidities. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 87:741–749.

Neuhauser, H., and T. Lempert 2004 Vertigo and Dizziness Related to Migraine: A Diagnostic Challenge. Cephalalgia 24(2):83–91.

Peris, F., S. Donoghue, F. Torres, A. Mian, and C. Wober 2017 Towards Improved Migraine Management: Determining Potential Trigger Factors in Individual Patients. Cephalalgia 37:452–463.

Peroutka, S.J. 2004a Migraine: A Chronic Sympathetic Nervous System Disorder. Headache 44(1):53–64.

Peroutka, S.J. 2004b Re: A Sympathetic View of “2003 Wolff Award: Possible Parasympathetic Contributions to Peripheral and Central Sensitization During Migraine”. Headache 44(7):731–732.

Peterlin, B.L., and A.I. Scher 2013 Migraine and the Social Selection vs Causation Hypotheses: A Question Larger Than Either/Or? Neurology 81(11):942–943.

Queiroz, L.P., D.I. Friedman, A.M. Rapoport, and R.A. Purdy 2011 Characteristics of Migraine Visual Aura in Southern Brazil and Northern USA. Cephalalgia 31(16):1652–1658.

Queiroz, L.P., A.M. Rapoport, R.E. Weeks, F.D. Sheftell, S.E. Siegel, and S.M. Baskin 1997 Characteristics of Migraine Visual Aura. Headache 37(3):137–141.

Raskin, N.H., and S.C. Knittle 1976 Ice Cream Headache and Orthostatic Symptoms in Patients with Migraine. Headache 16(5):222–225.

Russell, M.B., H.K. Iversen, and J. Olesen 1994 Improved Description of the Migraine Aura by a Diagnostic Aura Diary. Cephalalgia 14(2):107–117.

Russell, M.B., and J. Olesen 1996 A Nosographic Analysis of the Migraine Aura in a General Population. Brain 119(Pt 2):355–361.

Sacks, O.W. 1999 Migraine. New York: Vintage Books.

Sarnyai, Z., M. Berger, and I. Jawan 2016 Allostatic Load Mediates the Impact of Stress and Trauma on Physical and Mental Health in Indigenous Australians. Australasian Psychiatry 24(1):72–75.

Singer, M., and S. Clair 2003 Syndemics and Public Health: Reconceptualizing Disease in Bio-social Context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 17(4):423–441.

Theeler, B.J., R. Mercer, and J. C. Erickson 2008 Prevalence and Impact of Migraine among US Army Soldiers Deployed in Support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Headache 48(6):876–882.

Turner, R.J., C.S. Thomas, and T.H. Brown 2016 Childhood Adversity and Adult Health: Evaluating Intervening Mechanisms. Social Science and Medicine 156:114–124.

Viana, M., M. Linde, G. Sances, N. Ghiotto, E. Guaschino, M. Allena, S. Terrazzino, G. Nappi, P.J. Goadsby, and C. Tassorelli 2016 Migraine Aura Symptoms: Duration, Succession and Temporal Relationship to Headache. Cephalalgia 36:413–421.

Weatherall, M.W. 2015 The Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Migraine. Therapeutic Advances Chronic Disease 6(3):115–123.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted as per in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hinton, D.E., Reis, R. & de Jong, J. Migraine-Like Visual Auras Among Traumatized Cambodians with PTSD: Fear of Ghost Attack and Other Disasters. Cult Med Psychiatry 42, 244–277 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-017-9554-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-017-9554-7