Abstract

Presented paper contains results of fracture analysis of brittle composite materials with a random distribution of grains. The composite structure has been modelled as an isotropic matrix that surrounds circular grains with random diameters and space position. Analyses were preformed for the rectangular “numerical sample” by finite element method. FE mesh for the examples were generated using the authors’ computer program RandomGrain. Fracture analyses were accomplished with the authors’ computer program CrackPath3 executing the “fine mesh window” technique. Calculations were preformed in 2D space assuming the plane stress state. Current efforts focus on brittle materials such as rocks or concrete.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The problem of crack propagation in engineering materials assuming arbitrary stress state, is still a topic of current research. Basic modes of fracture: opening mode (mode I), sliding mode (mode II) and the tearing mode (mode III) [22] are convenient methods for estimating the strength of the material and the direction of crack propagation. In the case of brittle materials, which are often considered as the linear-elastic medium until failure, convenient approach is to apply linear-elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM). In this case, the adoption of Westergaard solution for the stress field around a crack tip gives the singularity of type \({1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {\sqrt r }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\sqrt r }}\) in the stress distribution, where r is the distance from the crack tip. Disadvantage of this can be avoided by taking stress intensity factors: \(K_{I} = \mathop {\lim }\limits_{r \to 0} \sqrt {2\pi {\kern 1pt} r} {\kern 1pt} \sigma_{yy} (\vartheta = 0),\quad K_{II} = \mathop {\lim }\limits_{r \to 0} \sqrt {2\pi {\kern 1pt} r} {\kern 1pt} \sigma_{xy} (\vartheta = 0),\quad K_{III} = \mathop {\lim }\limits_{r \to 0} \sqrt {2\pi {\kern 1pt} r} {\kern 1pt} \sigma_{yz} (\vartheta = 0)\), (see Fig. 10), as the material characteristics, determined respectively in the modes I, II and III by simple laboratory tests.

In the case of adoption of elasto-plastic material model disappear singularity of the stress field around the crack tip, which is surrounded by the plastic zone. This state is described by the elasto-plastic fracture mechanics (EPFM).

Another approach is characterized by cohesive zone model (CZM) proposed by Dugdale in 1960 and Barenblatt in 1962. This model assumes a small zone of weakened material (cohesive zone) in line the crack tip to avoid singularity of the stress field in the LEFM model. CZM is often used to model the destruction of brittle materials such as rocks and concrete.

The theoretical and numerical analyzes, which aim to predict the path of propagating cracks, criterion indicating the direction of crack propagation is particularly significant.

In simple conditions described by modes I, II and III it is evident, but in conditions of complex stress state and in particular a 3-axial stress state the different criteria are used. Classic criterion for the maximum tensile stress (MTS) proposed by Erdogan and Sih in 1963 [6] and modified by Sih [20] in 1974 a minimum strain energy (S) criterion—SED:

\(S = \frac{1}{{16\pi {\kern 1pt} G}}(a_{11} K_{I}^{2} + 2a_{12} K_{I} K_{II} + a_{22} K_{II}^{2} )\), where a 11, a 12, a 22 are functions of the ϑ angle (Fig. 10), and G is the shear modulus.

Theocaris and Andrianopoulos [23] modified this criterion by adding a volume strain energy term which is particularly important for materials characterized by internal friction. Here corresponds to the direction of crack propagation described by angle ϑ at which the portion of volumeric strain energy S H reaches a minimum at a constant of distortional energy portion S D :

where E is the Young’s modulus, ν—Poisson’s ratio, I 1 first invariant of the stress tensor and J 2—the second invariant of the stress deviator. The expression of this condition by means of two invariants of the stress tensor allows its easy application in any state of stress.

Criterion proposed by the author consisting in finding the direction of propagation defined by the angle ϑ for which the minimum is achieved for criterion depending on the 3 stress tensor invariants. This allows even better fit the criterion for material characteristics, in particular of the brittle material where relationship of the strength in a complex state of stress from J 3-invariant it is clearly visible [15].

A similar idea involving the dependence of the criterion on the stress invariants applied Papadopoulos [13], who assumed that the value of the 3rd invariant of the stress tensor I 3 = σ 1 σ 2 σ 3 reaches a maximum in the direction of crack propagation.

Synthetic overview of the different propagation criteria, both for linear model LEFM as well as non-linear EPFM, can be found in paper Mróz and Mróz [11].

The importance of accurately determine the stress fields around the crack tip describe Berto and Lazzarin [2, 3]. Precise determination of the crack direction is particularly important in the case of composites, which are composed of materials with different characteristics and also necessary to consider the interface layer at the border of these components. A number of different approaches to this problem can be found in the papers of Brighenti et al. [4] Carpinteria et al. [5] Honein and Herrmann [7], Kitagawa et al. [8] Murakami [12]. The use different criteria for the propagation of the polycrystalline material presents Sukumar and Srolovitz [21]. Application in the analysis of the material models in mesoscale can be found in the works of Wriggers and Moftah [25] and Mishnaevsky [10].

The paper presents a computer analysis of the fracture of the composite with a random structure, which well corresponds to the structure of concrete. The ways of geometry generation of such a composite, criterion for initiation of cracks and derived from it a condition specifying the direction of crack propagation is presented.

Presented computer simulation using finite element analysis, which shows the propagation of crack running between the grains of the composite. Because at such a complex structure it is not possible to directly apply the classical condition of crack propagation own criterion, based on condition of the material destruction, was applied.

Presented computer simulation gave promising results but it certainly should be confirmed by laboratory experiments, which the author is planning in the near future.

2 Generating the random structure of the model

For generating the geometry of the model containing randomly spread inclusions surrounded with matrix material, authors propose the Grains Neighbourhood Areas algorithm (GNA) [17] which creates models of the material in the way similar to the algorithm “larger first”, proposed by Van Mier and Van Vliet [24] or described by Wriggers and Moftah for 3D structure [25], however GNA works much more quickly. In the proposed method three random numbers generators based on probability distribution function are used: uniform, normal (Gauss) and Fuller. The generator of the Fuller distribution was obtained from the cumulative function for Fuller sieve curve. Diameters of grains which are located in the space of the model are calculated by the Fuller generator. The generator of the uniform distribution is used for receiving the angle in the polar coordinate system which describes direction of grain location. The generator of the uniform distribution is used also for determining the distance of next grains in the case of A-type samples and Gauss generator in case of B-type samples.

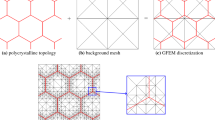

3 Idea of the GNA algorithm

For every grain its neighborhood area is considered. The neighborhood is defined as a circle with a given radius divided in 6 sectors (Fig. 1). In every unoccupied sector a new grain is tried to be placed. The process of placing a grain consists on generating polar coordinate (α, r): 0° < α ≤ 60°, R min ≤ r ≤ R max. If the generated grain does not collide with existing grains it is accepted. In other case new position is tried. The number of attempts N is the algorithm’s parameter which control grains packing. Such produced structure is discretize by finite element mesh. In presented papers following parameters has been assumed: grain diameters D min = 1 mm, D max = 8 mm; spaces between grains S min = D min, S max = D max. Number of attempts N = 10 which results in packing level at about 40 %.

-

The grains diameters D are calculated by the randomF generator (Fuller distribution) (Fig. 2)

-

Angle a in polar coordinate system is calculated by randomU generator (uniform distribution) (Fig. 3)

-

Case A—randomU (uniform) generator is used to determine distance between grains

-

Case B—randomG (Gaussian) generator is used to determine distance between grains (Fig. 4)

The differences between the areas obtained by RandomU generator (case A) and a generator RandomG (case B) are not significant. The samples are shown in the Fig. 5.

4 Material constants and FE mesh

The structure thus obtained was discretized in order to obtain the FE mesh. Boundary conditions and geometry of the model are shown in Fig. 6. A small notch in the middle of the left edge has been generated in order to ensure a controlled start of the crack.

Material constants that are used in the model are presented in Table 1, where E—Young modulus, v—Poisson ratio, f c —strength in uniaxial compression, f cc —strength in biaxial compression with σ 1 /σ 2 = 1, f 0c —failure stresses in biaxial compression with σ 1 /σ 2 = 2, f t —tension strength.

5 Analysis of cracking

Analysis of cracking was performed using the authors’ computer program CrackPath3, in which the technique of moving windows with the high density of the FE mesh was applied. This technique assumes the high density of the FE mesh in surroundings of the crack tip and the coarse mesh in area away from the crack.

Inside the window with fine mesh, material of composite is modeled as precisely as it is possible, while outside this window the composite is modeled as the homogeneous material with elastic characteristics determined in homogenizations procedures. The window with the fine FE mesh is moved with the top of the crack in every computational step or after a few steps (what shortens the computation time), in which position of the crack tip is being estimated (Fig. 3). The point in which the crack is initiated is determined at each calculation step using PJ failure criterion described in earlier papers of the author [14–16]. The shape of the limit surface associated with this condition is shown on Fig. 7.

6 PJ failure criterion

The criterion was proposed by author [14, 15] in 1984 in the form:

where \(P(J) = \cos \left( {\tfrac{1}{3}\arccos \alpha J - \beta } \right)\)—function describing the shape of limit surface in deviatoric plane, \(\sigma_{0} = \tfrac{1}{3}I_{1}\)—mean stress, \(\tau_{0} = \sqrt {\tfrac{2}{3}J_{2} }\)—octahedral shear stress, I 1—first invariant of the stress tensor, J 2, J 3—second and third invariant of the stress deviator, \(J = \frac{{3\sqrt 3 J_{3} }}{{2J_{2}^{3/2} }}\)—alternative invariant of the stress deviator, α, β, C 0, C 1, C 2—material constants.

Classical failure criteria, like Huber–Mises, Tresca, Drucker–Prager, Coulomb-Mohr as well as some new ones proposed by Lade, Matsuoka, Ottosen, are particular cases of the general form (1) PJ criterion.

Material constants can be evaluated on the basis of some simple material test results like:

-

f c —failure stress in uniaxial compression,

-

f t —failure stress in uniaxial tension,

-

f cc —failure stress in biaxial compression at σ1/σ2 = 1,

-

f 0c —failure stress in biaxial compression at σ1/σ2 = 2/1,

-

f v —failure stress in triaxial tension at σ1/σ2/σ3 = 1/1/1,

For concrete or rock-like materials some simplification can be taken on the basis of the Rankine–Haythornthwaite “tension cutoff” hypothesis: f v = f t.

Values of the material constants C 0, C 1, C 2 can be calculated from following equations:

where \(P_{0} = \cos \left( {{\kern 1pt} \tfrac{1}{3}\arccos \alpha - \beta } \right)\).

Values of the α and β parameters can by calculated from the author iterative formula [14, 15] or from equations proposed by P. Lewiński [9]:

where:

7 Crack propagation analysis

The technique of the moving window with fine mesh was presented in previous author papers [17, 18]. This simple re-meshing procedure considerably reduces (3 ÷ 4 of times) the numerical problem to solve what is related to reduction of the number of nodes in FE model.

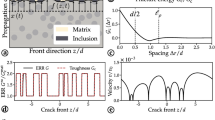

Inside the window with fine mesh, material of composite is modeled as precisely as it is possible, while outside this window the composite is modeled as the homogeneous material with elastic characteristics determined in homogenizations procedures. The window with the fine FE mesh is moved with the top of the crack in every computational step or after a few steps (what shortens the computation time), in which position of the crack tip is being estimated (Fig. 8). The point in which the crack is initiated is determined at each calculation step using PJ failure criterion.

Figure 8 are showing the result of calculations of the crack propagation paths with applying 4 windows (marked with letters A, B, C, D) of fine FE mesh. The mesh with this density allows making ca 80 calculation steps of the crack propagation without changing the window position.

In each crack step CrackPath3 program (see Table 2) calculates the stress field using finite elements methods and then it seeks the point of the crack initiation on the basis of the PJ criterion. This is the point of the highest value of the material effort (μ). The value of the material effort ratio μ is calculated based on the formula containing stress tensor components and material constants according to the PJ failure criterion.

where r σ and r f are radii in the stress space: \(r_{\sigma ,f} = \sqrt {\tau_{O}^{2} + \sigma_{O}^{2} }\) (see Fig. 9).

The crack is assumed to continue in direction φ 0 in which the derivative \(\left. {\frac{\partial \mu }{\partial r}} \right|_{\phi = \phi 0}\) get the minimum value: \(\left. {\nabla \mu (\phi_{0} ) = \frac{\partial \mu }{\partial r}} \right|_{\phi = \phi 0} \to \hbox{min}\) (Fig. 10c, d).

Material effort ratio for classical Westergaard stress field near crack tip, Drucker -Prager failure criterion was used for μ definition, a) coordinates near crack tip, b) concentration of the effort ratio near crack tip, c) field of the ∇μ—effort ratio derivative, d) ∇μ—φ dependency at r = 0.01 → φ0 = 0

Determination of the μ(x, y)—effort function, depending on the stress field and failure criteria used, can easily show on the example of classic problem of stress around the crack tip which has been solved by Westergaard [22]. For simplicity two-parameter Drucker–Prager failure criterion can be used which has a conical limit surface in the 3D space of principal stresses (Fig. 7a).

Stress field for the problem shown on Fig. 10a can be written as follows [22]:

Drucker–Prager criterion can be written by using stress invariants τ 0 and σ 0 as follows:

where c and b are the criterion parameters and they can be calculated on the basis of simple laboratory data as compressive strength f c and tensile strength f t. Writing conditions for these 2 points in the 2D stress state we get:

With conditions that describe compression test (7a) we get \(\tau_{0} = \frac{\sqrt 2 }{3}f_{c} ,\quad \sigma_{0} = - \frac{1}{3}f_{c}\) and from tension test (7b) \(\tau_{0} = \frac{\sqrt 2 }{3}f_{t} ,\quad \sigma_{0} = \frac{1}{3}f_{t}\) after that easily will receive the parameters:

Taking compressive strength f c = 10 MPa and a tensile strength f t = 2 MPa we obtain b = 0.9428 and c = 2.8284 MPa.Based on the relationship shown on Fig. 9b, we have:

Thus we have the desired effort function:

Graph of the μ function around the crack tip is shown in Fig. 10b and its derivative ∇μ is shown in Fig. 10c. The diagram Fig. 10d shows a cross-section of the ∇μ surface by the cylinder of radius r = 0.01. Visible is the minimum point of this section, which, according to the prediction occurs at φ = 0.

Assuming other criteria (e.g. JP) and material heterogeneity we get much more complex terms describing the angle of crack propagation. Charts of the material effort for the heterogeneous composite with strong circular inclusions is shown in Fig. 11. It was made on a FEA mesh based on stress calculated numerically, JP condition was used.

Known and described in the literature are several criteria of crack propagation, starting from the classic conditions of Griffith’s maximum energy release rate criterion by the condition of minimum strain energy density proposed by Erdogan and Sih and somewhat similar to condition described above, Papadopoulos Det-criterion [13]. Overview of the many conditions of crack propagation in homogeneous materials can be found in the paper of Mróz and Mroz [11].

Conditions for predicting of cracks propagation in heterogeneous materials such as composites, geomaterials and polycrystalline materials are much more complex. There may be mentioned, for example, the approach proposed by Honein and Herrmann [7] and Sukumar and Srolovitz [21], where considered materials similar to that described in this work.

The proposed simple, local criterion for composites with brittle matrix makes it easy to predict the direction of crack propagation. Criterion has been repeatedly used by the author and colleagues in numerical analyzes of crack rocks and concrete, where the predominant failure modes corresponding to the open crack—mode I.

After finding the direction of the crack propagation, a FE mesh is modified in surroundings of the crack tip in order to add the next crack segment with the length equal to the size of the cracked element. The procedure is carried on until the demanded number of steps is achieved or the crack stops propagating [18, 19], Fig. 12.

The propagation of the analyzed crack was performed on FE mesh consisted of 20,498 (window A) up to 42,326 (window C) nodes. For comparison purpose calculations for models without the windows were also performed: Model 2—16,032 and Model 3—31,311 nodes. In the last two cases, paths of the crack are less stable and the calculations times are comparable to the time needed for the Model 1. The hypothetical model 4, with mesh density comparable to the model 1, would require execution time 20 times longer to calculate 10 steps of the crack.

Windows with the fine FE mesh presented in this paper were generated as a circle with the radius r ≅ 10 mm, created around of the crack tip. Grains lying on the border of the circle were included in this domain in order to make impossible creation of artificial effects of the stress concentration on the border of homogenized material. Model shown on Fig. 3 (Model 1 with windows A, B, C, D) was created assuming material constants given in the Table 1.

Other methods of analysis of crack propagation in the heterogeneous materials were described e.g. in papers: Bažant [1], Carpinteri and others. [5], Mishnaevsky [10].

Known and described in the literature are several criteria of crack propagation, starting from the classic conditions of Griffith’s maximum energy release rate criterion by the condition of minimum strain energy density proposed by Erdogan and Sih and somewhat similar to condition described above, Papadopoulos Det-criterion [13]. Overview of the many conditions of crack propagation in homogeneous materials can be found in the paper of Mróz and Mroz [11].

Conditions for predicting of cracks propagation in heterogeneous materials such as composites, geomaterials and polycrystalline materials are much more complex. There may be mentioned, for example, the approach proposed by Honein and Herrmann [7] and Sukumar and Srolovitz [21], where considered materials similar to that described in this work.

8 Conclusions

Simulation of the crack propagation for composite materials by FE method requires precise remeshing technique and very fine element mesh. The method of movable window with high mesh density seems to be a promising solution technique for problems requiring a high discretization level at a local scale. Cracking analyses of geomaterials with random structures fit naturally in this group. The CrackPath3 computer code uses the new criterion for prediction of the crack propagation direction which is simpler than suggested for polycrystalline materials by Sukumar and Srolovitz [21].

The proposed simple, local criterion for composites with brittle matrix makes it easy to predict the direction of crack propagation. Criterion has been repeatedly used by the author in numerical analyzes of crack in rock and concrete, where the predominant failure modes corresponding to the open crack—mode I. Presented computer simulation gave promising results but it certainly should be confirmed by laboratory experiments. Certainly would be interesting testing the behavior of crack propagation in three-dimensional models. This type analysis with FE models is planned as the subject of next works of the author.

Abbreviations

- a, b :

-

Constants in the Drucker–Prager failure criterion

- a 11 , a 12 , a 22 :

-

Constants in Sih strain energy density (SED) criterion

- G :

-

Kirschhoff (shear) modulus

- E :

-

Young modulus

- v :

-

Poisson ratio

- f t :

-

Tension strength

- f c :

-

Strength in uniaxial compression

- f cc :

-

Strength in biaxial compression with σ 1 /σ 2 = 1

- f 0c :

-

Failure stresses in biaxial compression with σ 1 /σ 2 = 2

- f v :

-

Failure stress in triaxial tension at σ 1 /σ 2 /σ 3 = 1/1/1,

- σ 1, σ 2, σ 3 :

-

Principal stresses

- \(P(J) = \cos \left( {\tfrac{1}{3}\arccos \alpha J - \beta } \right)\) :

-

Function describing the shape of limit surface in deviatoric plane

- α, β :

-

Constants in the P(J) function

- C 0, C 1, C 2 :

-

Constants in the JP failure criterion,

- \(\sigma_{0} = \tfrac{1}{3}I_{1}\) :

-

Mean stress

- \(\tau_{0} = \sqrt {\tfrac{2}{3}J_{2} }\) :

-

Octahedral shear stress

- \(\kappa = \frac{{\tau_{0} }}{{\sigma_{0} }}\) :

-

Octahedral stress ratio

- I 1 = σ 1 + σ 2 + σ 3 :

-

First invariant of the stress tensor,

- I 3 = σ 1 σ 2 σ 3 :

-

Third invariant of the stress tensor

- J 2, J 3 :

-

Second and third invariant of the stress deviator

- \(J = \frac{{3\sqrt 3 J_{3} }}{{2J_{2}^{3/2} }}\) :

-

Alternative invariant of the stress deviator

- \(\mu = \frac{{r_{\sigma } (\sigma )}}{{r_{f} (\sigma )}}\) :

-

Material effort ratio

- r σ :

-

Distance in the stress space between origin of the coordinate system σ 1, σ 2, σ 3 and stress point σ:\(r_{\sigma } = \sqrt {\tau_{O}^{2} + \sigma_{O}^{2} }\)

- r f :

-

Distance in the stress space between origin and limit surface in direction parallel to r σ

- x,y :

-

Cartesian coordinate

- r, φ:

-

Polar coordinate

References

Bažant Z (2002) Concrete fracture models: testing and practice. Eng Fract Mech 69:165–205

Berto F, Lazzarin P (2010) On higher order terms in the crack tip stress field. Int J Fract 161:221–226

Berto F, Lazzarin P (2013) Multiparametric full-field representations of the in-plane stress fields ahead of cracked components under mixed mode loading. J Fatigue 46:16–26

Brighenti R, Carpinteri A, Spagnoli A (2014) Influence of material micro-voids and heterogeneities on fatigue crack propagation. Acta Mech 225:3123–3135

Carpinteri A, Chiaia B, Cornetti P (2003) On the mechanics of quasi-brittle materials with a fractal microstructure. Eng Fract Mech 70:2321–2349

Erdogan F, Sih GC (1963) On the crack extension in plates under plane loading and transverse shear. J Basic Engng. 85:519–527

Honein T, Herrmann G (1990) On bonded inclusions with circular or straight boundaries in plane elastostatics. J Appl Mech Trans ASME 57:850–856

Kitagawa H, Yuuki R, Ohira T (1975) Crack-morphological aspects in fracture mechanics. Eng Fract Mech 7:515–529

Lewiński P (1996) Nieliniowa analiza osiowo-symetrycznych konstrukcji powłokowych. Prace Naukowe PW 131:73

Mishnaevsky L (2007) Computational mesomechanics of composites. Wiley, New York

Mróz KP, Mróz Z (2010) On crack path evolution rules. Eng Fract Mech 77:1781–1807

Murakami Y (2002) Metal fatigue: effects of small defects and nonmetallilc inclusions. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Papadopoulos GA (1987) The stationary value oh the third stress invariant as a local fracture parameters (Det-criterion). Eng Fract Mech 27:643–652

Podgórski J (1984) Limit state condition and the dissipation function for isotropic materials. Arch Mech 36:323–342

Podgórski J (1985) General failure Criterion for isotropic media. J Eng Mech ASCE 111:188–201

Podgórski J (2002) Influence exerted by strength criterion on direction of crack propagation in the elastic-brittle material. J Min Sci 38(4):374–380

Podgórski J, Nowicki T, Jonak J (2006) Fracture analysis of the composites with random structure, IWCMM 16, Sep 25–25, 2006. Lublin, Poland

Podgórski J, Nowicki T (2007) Fine mesh window technique used in fracture analysis of the composites with random structure, CMM-2007 - Computer Methods in Mechanics, June 19–22, 2007. Łódź-Spała, Poland

Podgórski J, Sadowski T, Nowicki T (2008) Crack propagation analysis in the media with random structure by fine mesh window technique, WCCM8, ECCOMAS 2008, June 30–July 5, 2008. Venice, Italy

Sih GC (1973) Some basic problems in fracture mechanics and new concepts. Eng Fract Mech vpl. 5:365–377

Sukumar N, Srolovitz DJ (2004) Finite element-based model for crack propagation in polycrystalline materials. Comput Appl Math 23(2–3):363–380

Sun CT, Jin ZH (2012) Fracture Mechanics. Academic, Elsevier Inc, Amsterdam

Theocaris PS, Andrianopoulos NP (1982) The Mises elastic–plastic boundary as the core region in fracture criteria. Eng Fract Mech 16:425–432

Van Mier JGM, Van Vliet MRA (2003) Influence of microstructure of concrete on size/scale effects in tensile fracture. Eng Fract Mech 70:2281–2306

Wriggers P, Moftah SO (2006) Mesoscale models for concrete: homogenisation and damage behaviour. Finite Elem Anal Des 42:623–636

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Podgórski, J. The criterion for determining the direction of crack propagation in a random pattern composites. Meccanica 52, 1923–1934 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11012-016-0523-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11012-016-0523-y