Abstract

This paper investigates audit committee (AC) practices in relation to the oversight of financial reporting and external auditors. We conducted semi-structured interviews of Polish public interest entities to explore AC processes in a different environment from the widely researched Anglo-American model of corporate governance. The results of the study highlight the complexity and contradictory nature of solving governance issues in an environment characterized by a high concentration of ownership. Monitoring is stronger for companies whose dominant shareholder is a foreign investor. Local firms are generally slower to embrace an AC as an effective tool of oversight for financial reporting and external auditors. In general, the processes utilized by ACs are similar to those reported in the literature. The collected evidence does not provide support for a single dominant theory that explains the actual practices of ACs. In fact, multivocality proves to be a more useful approach for explaining various aspects of AC practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The audit committee (AC) plays an important role in corporate governance. Because of the separation of corporate management and ownership, supervisory boards protect shareholders’ interests because managers may not always act in the best interest of shareholders (Fama 1980; Fama and Jensen 1983; Jensen and Meckling 1976). Thus, the goal of the board of directors/supervisory board is to oversee management activities. Because of the diverse responsibilities of a board of directors/supervisory board, some of its oversight responsibilities must be delegated to various committees. The role of an AC is to oversee financial reporting, internal control, external auditors, and business risks. The importance of ACs has recently been emphasized after a series of financial scandals at the turn of the century, with Enron as the most spectacular.

ACs have attracted increasing attention from regulators, practitioners, and researchers. A number of accounting firms and practitioners have advocated approaches and guidelines for more effective ACs (KPMG 2004). A number of these recommendations have been incorporated into well-known laws and regulations, such as the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) in the United States (US) and the Combined Code in the United Kingdom (UK). Regulators have assigned various duties to auditing committees, including the oversight of financial reporting and external auditors. These two duties are considered important factors in ensuring both the integrity of financial reporting and the ability of financial consumers to make informed decisions.

At the European level, the European Parliament and Council amended the Eighth Directive on Company Law requiring public interest companies to establish an AC, which shifted the focus from the need for ACs to the effectiveness of existing ACs. The amended directive thus created broader possibilities to study ACs outside of the environment of Anglo-Saxon corporate governance.

Prior research (Aguilera et al. 2008) indicates that the interdependencies of companies and their business environments and cultures can lead to differences in effective governance practices. Thus, there is no reason to assume that the solutions that are suitable in a specific environment will be efficient in a different setting. In addition, a number of previously published works call for AC research outside of the Anglo-Saxon world (DeZoort et al. 2002; Bedard and Gendron 2010; Carello et al. 2011; Böhm et al. 2012).

The goal of this paper is to study ACs (and, therefore, corporate governance and accounting in action) as described by Gendron (2009). A number of accounting researchers have been called upon to study social objects—including accounting—by employing diverse perspectives and lenses (Cooper and Morgan 2008; Burchell et al. 1980; Hopwood 1983). Because social interactions (including corporate governance practices) can be complex, ambiguous, and contradictory, there has been a call for more context-based studies of ACs. The practices of ACs are vital to better understand and improve our knowledge of the substance of AC activities and the role of ACs in ensuring the overall effectiveness of corporate governance mechanisms (Spira 1999; Turley and Zaman 2004; Gendron and Bédard 2006; Gendron 2009).

This paper offers a potential contribution to the literature by providing further insights into specific AC processes in a setting outside the Anglo-Saxon corporate governance model. It is a response to calls for research into governance processes (not simply governance characteristics, such as independence and financial expertise) and for examination of corporate governance in different settings, particularly in countries that do not follow the Anglo-American governance model (Carcello et al. 2002; Bedard and Gendron 2010; He et al. 2009). For instance, Bedard and Gendron (2010) noted in their summary that “our review also highlights important gaps in the literature. Most studies are relational and explanatory; few are exploratory, descriptive and transformative. Psychological and sociological perspectives of analysis are neglected. Knowledge is scant on ACs in jurisdictions that do not follow the Anglo-Saxon model of corporate governance. Further, research on dynamics surrounding AC processes is scarce.”

Unlike other papers that have explored the effectiveness of ACs in general, this paper provides greater insight into specific aspects of AC effectiveness in an insider setting. Previous studies have indicated that the effectiveness of ACs has increased over time. Based on US data, Beasley et al. (2009) concluded that AC members strive to provide effective monitoring of financial reporting and to avoid serving on ceremonial ACs. However, in the six specific AC process areas that were investigated (accepting and continuing due diligence processes, selecting AC nominees, AC meeting processes, AC oversight of financial reporting processes, oversight of internal and external audit processes, and other AC activities), the evidence is mixed. By performing a more in-depth investigation of selected processes connected to financial reporting and external auditors (and by identifying the strengths and weaknesses of practices related to these processes), this paper may have implications for improving the overall quality of corporate governance.

In addition, this study offers evidence about practices in a corporate governance system characterized by a high concentration of ownership. The background for the development of a free-market economy consists of the establishment of capital markets and effective capital market institutions. In Polish corporate governance, these specific developmental features are associated with the manner in which privatization was executed during the transition from a centrally planned economy to a market-based economy. The privatization program in Poland led to a capital market characterized by significant concentration of ownership. The structure of shareholding has changed over time, with the average shareholdings of the largest owners in privatized firms at 34 % in 1996 and 50 % in 2000. The highest ownership concentrations (up to 75 %) are observed in firms that have been bought by foreign investors (Grosfeld and Hashi 2007). Another reason for choosing Poland as a research site is that it has a relatively young capital market and is representative of countries of the so-called “New (enlarged) Europe”; Poland entered the EU in 2004 after a rapid economic transformation. Although there has been some global convergence in AC practices, the effectiveness of ACs in transition economies may be limited by the availability of appropriate human resources and the time to develop effective AC practices. This may be particularly apparent in an environment with concentrated ownership, in which strong owners enjoy the benefits of private control and may restrain the initiatives and incentives of other shareholders to acquire information and control managerial decisions. An AC’s effectiveness in this “insider” model of corporate governance is likely to be limited.

Given the fragmentary nature of the evidence about corporate governance in general (and with papers focusing primarily on the Anglo-Saxon world), this study provides additional insight into corporate governance in Poland. Based on the above discussion, three sets of research questions emerge for this study:

-

1.

How do ACs perform their monitoring duties regarding the oversight of financial reporting and external auditors? How are ACs involved in the process of external auditor selection?

-

2.

What resources are available to ACs for effectively performing these duties?

-

3.

What are the critical factors that affect AC efficiency? Does an environment characterized by a high concentration of ownership influence the practices and processes of ACs?

This paper is structured in seven parts. Section 1 introduces the context and presents the main reasons for undertaking this study. Section 2 presents a literature review related to AC effectiveness and, more specifically, to AC processes and resources. Section 3 introduces the context of the present study by providing background information about the corporate governance system and ACs in Poland. Section 4 offers information about the research method. Section 5 presents the findings of the AC. Section 6 provides a discussion using the three sets of guiding research questions as an organizational framework. Section 7 summarizes our conclusions and illustrates possible directions for further research.

2 Audit committee (AC) research

A review of the literature reveals that a number of papers have presented summaries of research or meta-analyses about ACs (DeZoort et al. 2002; Cohen et al. 2004; Turley and Zaman 2004; Cohen et al. 2007; He et al. 2009; Bedard and Gendron 2010; Carello et al. 2011). Most papers have examined a variety of process issues primarily by interviewing both AC members and internal and external auditors. These studies have found contradictory evidence about substantive/ceremonial and formal/informal AC processes. This literature review indicates that the resources (characterized mainly by independence, knowledge, and expertise) in the hands of ACs have generally increased over time, particularly in the post-SOX period. An overview of the AC literature related specifically to AC processes and resources is presented below.

Beasley, Besley et al. (2009) examined the AC process by exploring practices in 42 US public companies in the post-SOX era and found a variety of AC practices. However, AC members are increasingly becoming more engaged in the substantive monitoring of financial reporting.

Cohen et al. (2002) studied auditor experiences in their interactions with ACs and boards of directors in the US and the resulting effects on the audit process. They found that auditors’ experiences with ACs were less than satisfactory. ACs were often found to lack the financial expertise, authority and skepticism necessary to be effective. The auditors came to understand the ACs as passive governance instruments that played merely a ritualistic role. In a later study from the post-SOX era, the same authors (Cohen et al. 2010) found that the role of the AC had changed: auditors now considered the board and the control environment as important actors in a firm’s governance structure. However, management was still understood to be the key driver in determining auditor appointments and terminations, although certification requirements by CEOs and CFOs had a positive effect on the integrity of financial reporting. ACs were considered to have sufficient expertise and authority to fulfill their responsibilities; members of ACs played important roles in overseeing internal controls, maintaining reporting quality, ensuring sufficient audit fees, identifying risks, asking challenging questions, and overseeing the whistle-blowing process. In yet another study, Cohen et al. (2007) found that auditors perceived ACs to be more diligent, active, and expert after the introduction of SOX. However, Fiolleau et al. (2013) reported a significant involvement of management in the auditor selection process.

Gendron et al. (2004) provided insights into AC meeting practices, including meetings in which members met privately with auditors. The study highlighted the key matters that AC members emphasized during meetings, such as the accuracy of financial statements, the appropriateness of the wording used in financial reports, the effectiveness of internal controls, and the quality of work performed by the auditors. The ACs that was examined generally perceived themselves as effective.

In the UK, Spira (1999, 2002, 2003) determined that AC activities were more ceremonial in nature and that the AC was a seeker and provider of comfort to CFOs and various consumers of auditing and financial statements and reports. Another study by Turley and Zaman (2007) determined that AC’s greatest impact was represented in informal processes, such as meetings with auditors or management.

Studies related to AC effectiveness indicate an increasing demand for AC resources and responsibilities (Carcello et al. 2002; Carcello and Neal 2000; DeZoort 1997; DeZoort et al. 2002; DeZoort and Salterio 2001). DeZoort et al. (2002) provided a framework for the evaluation of AC effectiveness and synthesized the literature into four components: AC composition, AC authority, AC resources and AC diligence.

Vafeas (2001) found that members appointed to an AC had significantly less board tenure with the firm, served on fewer committees and were less likely to serve on other committees. AC members were more likely to be “grey” directors (with a past or present relationship with the firm or its management). Carcello et al. (2002) examined the US market by looking at AC disclosures in charters and reports. The authors reported discrepancies between descriptions of ACs and their actions. The findings of the study indicate that there was a generally high level of compliance across firms with respect to compulsory disclosures and voluntary disclosures of AC activities were more prevalent in larger companies with independent ACs. Prior to enactment of SOX, studies also reported a large number of grey directors on ACs (Vicknair et al. 1993). Studies related to AC independence suggest a correlation with the independence of the board (Klein 2002; DeZoort and Salterio 2001).

As for knowledge and expertise, DeZoort (1997) found that AC members were not fully aware of their formal responsibilities when comparing their responses to those reported in a company’s proxy statement. This experimental study showed that AC members with experience were more likely to execute effective oversight of the external auditor. Because it selects the AC, the board exerts significant influence on AC quality (Beasley and Solterio 2001).

Collier and Zaman (2005) studied the AC concept in the European setting and found that it has become accepted in European governance codes in countries with both one- and two-tier corporate governance systems. Turley and Zaman (2007) found that informal networks between AC participants condition the AC’s impact and that the most significant effects of the AC on governance outcomes occur outside the formal structures and processes. In a developing country setting, Al-Twoijry et al. (2002) found that AC resources in Saudi Arabia were limited and that AC members lacked terms of reference, restrictions on the scope of work, independence, a working relationship with external and internal auditors, and experience.

Gendron and Bédard (2006) adopted a social constructivist approach to better understand the processes by which meanings regarding AC effectiveness are internally developed and sustained within the small group of people who attended AC meetings. Drawing on Latour (1987), the researchers argued that perceptions of the actors involved in internal processes constitute an “obligatory passage point” to make sense of and understand the effectiveness of ACs. Their paper examined the processes by which meanings of effectiveness are internally produced within the small group of actors involved in the corporate governance process.

The importance of corporate governance for emerging market economies has been widely recognized. However, the debate has focused on issues such as privatization, board composition, executive compensation, hostile takeovers and shareholder activism, corporate governance disclosures, and the general performance of corporate governance systems (Mickiewicz 2009; Berglof and Sarmistha 2007; Mallin and Ranko 2000; Koładkiewicz 2001; Filatotchev et al. 2007a, b, c; Filatotchev 2006; Tamowicz and Dzierzanowski 2003). The research related to ACs in this context is limited. Zain and Subramaniam (2007) examined internal auditors’ perceptions of AC interactions in Malaysia. They found no clear reporting lines and infrequent interaction of internal auditors with ACs. Al-Twoijry et al. (2002) studied AC practices in Saudi Arabia and concluded that ACs lack the resources to be effective.

In sum, ACs are well researched social objects in the setting of the Anglo-American governance model. However, the review of literature indicates a gap in knowledge related to the other setting like insider model of corporate governance, characterized, among others by high concentration of ownership. Also, a review of literature on corporate governance in emerging markers indicates little understanding of AC practices this context.

3 Setting up the context: corporate governance and ACs in Poland

Despite the scarcity of published literature on ACs in developing countries, studies show that these countries are making efforts to improve their corporate governance systems. International organizations such as the World Bank and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) provide guidelines for corporate reforms in many developing countries. The European Union (EU) is also undertaking efforts to reform the corporate governance systems of its member states (Official Journal of the European Union 2005). At the local level, regulators and local stock exchanges have also introduced changes and new requirements related to corporate governance, often in the form of Corporate Governance Codes (CGCs), which are a set of best-practice recommendations regarding the behavior and structure of the board (Aguilera and Cuervo-Cazurra 2009).

Poland is an example of these changes outside the well-researched Anglo-Saxon world. The Polish corporate governance system in its current stage has emerged over the last 20 years with reforms that simultaneously encompass ownership transformation and the building of a market-based financial system, including the establishment of a capital market (Koładkiewicz 2001). The contemporary corporate governance system in Poland can be characterized as the “insider” model of corporate governance, in which owners monitor, oversee, and control companies from within. In this model, owners frequently take large ownership stakes in individual companies and actively cooperate with management, which enables investors to retain direct hierarchical control over management and reduce agency costs. Therefore, individual investors often have large ownership stakes. In the insider model of corporate governance, the board of directors is often replaced by a supervisory board.

Since 1990, Poland has successfully walked down the path toward a market economy. This rapid economic transition could not have been achieved without a rapid privatization program and the establishment of a vibrant stock market. The Warsaw Stock Exchange (WSE) opened its first trading session on April 16, 1991 with only five listed companies. Today, the WSE is a medium-sized stock exchange with a leading position in Central and Eastern Europe, with a main market capitalization on December 31, 2010 of 201,132.32 million Euros and 400 traded companies.

The rapid development over the transition period has aimed at catching up with developed economies (through neither evolution nor revolution) and improving capital market and financial institutions. Unlike mature markets in which strong corporate governance mechanisms are considered a precondition of an effectively functioning capital market, corporate governance and capital markets develop simultaneously in emerging economies (Dobija and Klimczak 2010). In 2011, the Polish governance system may be characterized as follows:

-

(a)

A continental model of a two-tiered governance system in which the supervisory and management boards are separate. Consequently, the independence of the supervisory board members is a problematic issue. Since 2002, the CGC recommended the presence of independent supervisory board members;Footnote 1 however, this recommendation was rarely adhered to (Dobija et al. 2011).

-

(b)

A significant ownership concentration with dominant shareholding, in which the dominant shareholder’s stake is approximately 41 % and executives are the most frequent dominant shareholders (Aluchna 2007). Aluchna also notes that the significant dominance of executives in ownership is the result of a pyramid approach in which many domestic companies are controlled by the executives of a parent company.

-

(c)

Low enforceability of external monitoring mechanisms and transparency rules (Kuchenbeker 2008).Footnote 2

Aguilera and Cuervo-Cazurra (2009) describe two possible mechanisms for corporate code implementation, mandatory and voluntary. The first mechanism implements codes through the development of corporate legislation, such as SOX. The second mechanism uses voluntary self-regulation and is based on the rule of “comply and explain,” in which it is not required that companies comply with all code recommendations. Instead, companies are required to state how they have applied the principles in the code; non-compliance must be justified (e.g., the UK Combined Code of 2009).

Initially, Poland chose the second mechanism of CGC implementation—self-regulation. Seven years later, the voluntary principles related to the existence of ACs were replaced by mandatory regulation. When the first CGCFootnote 3 was introduced in Poland in 2002, there was no direct reference to an AC. However, one of the rules recommended the presence of an independent supervisory board member while selecting an external auditor. The second version of the CGC, issued in 2005, recommended the creation of an AC and a remuneration committee. The CGC recommended that all members of an AC be independent. The 2005 CGC also recommended a rotation of external auditors every 5 years. These independence criteria were deemed too strong for an emerging corporate governance system characterized by a high concentration of ownership. Thus, after 3 years of experience with the CGC, a new version was created that relaxed the requirements regarding the committees and their membership. The 2008 CGC recommended at least two independent board members and abolished the recommendation for a remuneration committee. The CGC continued to recommend the creation of an AC with at least one independent member with “competence” in the area of accounting and finance. For the criteria related to independence (and for a detailed description of the responsibilities of the AC), the CGC recommended the use of the EU recommendations (Official Journal of the European Union 2005). A timeline for the development of corporate governance regulation in Poland, including regulations for ACs, is presented in Table 1.

With the changes to the Eighth EU Company Law Directive on 17 May 2006, the EU countries began the process of adjusting their regulations to the European Law. In 2009, Poland issued new legislation regulating the role of ACs. The new regulation was included in a Parliamentary Act on Certified Auditors, their Self-government, and Entities Authorized to Audit Financial Statements and Public Supervision (Journal of Laws 2009). The establishment of the AC on a supervisory board was now formally requested, and the responsibilities of the AC were set on a mandatory basis. The responsibilities listed in the Act included the oversight of financial reporting, internal control systems, internal audits, risk management, and external audits, in addition to establishing the independence of the auditor. The Act also specified that the AC recommend an audit firm. According to the regulation, the AC should have at least three members, at least one of who should be independent and possess qualifications in accounting or financial auditing. A summary of the Polish regulations and legislation related to ACs is presented in Table 2.

It is rather surprising that AC regulations are included in the legislation related to accounting and auditing. The WSE does not have an enforcement mechanism for the establishment of ACs. Companies are requested only to submit a compliance report in which information about the AC should be included.

4 Research method

This study adopts an exploratory qualitative study method to examine AC practices in transitioning economy. Qualitative studies are generally better than quantitative studies at exploring a new phenomenon; they offer better descriptions of the phenomenon because they permit details naturally suppressed in studies of large samples (Silverman 1985; Patton 2002).

One of the important aspects of qualitative and interpretive research is a well-kept balance between rigor and openness (Ahrens and Chapman 2006). Openness can be achieved through methodological flexibility and multivocality, which, according to Gendron (2009:127), are not independent of one another. Methodological flexibility allows for the adoption of data collection and analysis according to the emergence of important trends and patterns from the data. For instance, Patton (2002) stressed that the researcher is not required to be locked into rigid methodological designs that eliminate responsiveness. Multivocality, however, relates to the belief that diverse theories can be simultaneously descriptive of a reality, as no single theory, perspective of analysis, or method of producing knowledge can account for the complexity of human behavior (Gendron 2009:127).

The primary research was conducted from January 2009 to June 2010. In May 2009, a new auditing act was introduced in Poland, which became effective in 2010. The new legislation required the establishment of ACs and their active involvement in financial reporting oversight as well as cooperation with external auditors. It was assumed that the introduction of the new regulation would not have a direct influence on the research sample—particularly in relation to the second stage of the research—as the companies in question were selected because their AC was active. The new legislation could be considered to have institutionalized practices previously in existence. Because the research focused on the practices of ACs in companies in which ACs were previously functioning, the archival data analysis concentrated on the information reported by companies in relation to the practices of ACs that were previously active. The new legislation was likely to affect the number of companies reporting the existence of an AC but less likely to change the practices of existing committees.

The subjects of our study were the ACs of companies listed on the WSE. The primary data were collected during fieldwork. The archival documentation was reviewed and interviews were conducted. The archival data were primarily obtained from publicly available sources such as corporate websites and financial data services, in addition to from the companies directly. Reports and charters of supervisory boards and ACs were retrieved. Other documentation, such as annual reports and corporate governance reports filed with the WSE, were reviewed for 2009.

Semi-structured in-depth interviews with AC members were conducted. To ensure construct validity (McKinnon 1988), the questions were designed to reflect the following key theoretical constructs (Silverman 1985; Patton 2002): the resources and expertise of the AC, the meeting process, involvement in external auditor selection, and oversight of financial reporting and other issues, including AC efficiency. The research instrument included a set of 20 questions divided into 4 groups (Appendix 1). In accordance with standard practices of qualitative research, the interview questions were refined during the fieldwork period based on the responses of the interviewees (Yin 2003). The respondents were informed about the purpose of the session. Prior to the interview, they were instructed that the interview’s purpose was to collect their own experiences with ACs and that, therefore, they should not be afraid of providing incorrect answers. The interviewed AC members were assured that their responses would be used in strict confidence. They were also asked for their permission to record the interview. To provide a reasonable comfort level related to sensitive data, the interviewees who allowed session recordings were also instructed that, in the case of sensitive information, they could ask the interviewer to switch off the recording device. In the event of such a request, the interviewer took notes and recorded a summary of the missing parts immediately after the interview.

The subjects of the study were AC members of companies listed on the WSE. In total, 16 interviews were conducted. Because AC practices are relatively new phenomena, it was difficult to gain access to many AC members willing to share their insights into their AC’s practices. We began the research with the goal of interviewing 30 AC members; however, only 16 persons agreed to be interviewed. One of the main reasons given for rejection was the that development practices in the candidate’s AC remained in its early stages. Details of the participants, the companies selected, and the interviews are presented in Appendix 2. Most of the interviews were recorded and transcribed. A draft report was presented to the interviewees to allow for comments on the reliability, validity and overall credibility of the observations and conclusions (Patton 2002).

Once the data had been collected, collated, and transcribed for each stage, they were manually coded using the key theoretical constructs (Ahrens and Dent 1998). Patterns and exceptions were identified in the coded data (Ahrens and Dent 1998). Two independent coders read all materials independently of one another and coded them into the same summary table. Coding differences were discussed and resolved by the two coders. The patterns that emerged from the data were then compared with prior research on ACs. The results were documented once this process was complete. A similar process of pattern identification was undertaken for the document review process. This process is consistent with the pattern matching described by Ahrens and Dent (1998). The results section of the paper discusses the elements coded in this table.

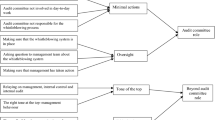

5 Results

This study determined that the AC construct may be adopted in a setting outside the Anglo-American world. However, during the dominance of the best-practice model, the process of adoption was rather slow and was generally apparent only in the case of the largest listed companies. The evidence collected in this paper does not provide a clear picture of the effectiveness of ACs. Some organizations, particularly those with majority shareholding in the hands of foreign investors, implement AC practices and processes aimed at the effective monitoring of management. In other cases, when dominant shareholding is in the hands of management or one entrepreneurial family, the picture is a bit different. In these cases, the need for an effective AC is more relaxed, as the monitoring of management can be undertaken directly by the owners.

The following three subsections present the major findings from the interviews on the oversight of financial reporting and external auditor processes (Sect. 5.1), critical resources required for effective monitoring (Sect. 5.2), and the critical factors affecting AC efficiency (Sect. 5.3).

5.1 AC oversight of financial reporting and external auditor processes (Q1)

The interview records of the actual practices related to the setting/reviewing of accounting policies and of alternative accounting treatments are mixed and range from no monitoring to a more substantial overview, which is actually consistent with previous studies (Beasley et al. 2009). The data analysis reveals that approximately 30 percent of ACs did not set/review accounting policies or alternative accounting treatments. In many cases, AC members considered financial reporting to be the domain of the management board and felt no reason to interfere beyond simply accepting the policies without discussion. One respondent suggested minimal involvement, whereas nearly 70 % confirmed some engagement in the setting of accounting policies. However, when performing this oversight, AC members primarily relied on the external expertise and judgment of the external auditors in most cases. An internal auditor would sometimes also be questioned about the appropriateness of a selected accounting policy and alternative accounting treatments.

Participant 8:

We are not concerned with accounting policies as there is something like IFRS and all public companies have to use them. You look at the most recent auditor’s report and you see if the company uses accounting policies in the right way. Sometimes, we also discuss some specific issues, like accounting policy and cost allocation procedures. But usually there are only one or at most two members of the supervisory board who seem to understand anything from the discussion.

For the oversight of financial risks (similar to the oversight of accounting policies), the degree and scope of the involvement also varied among respondents. However, the data revealed that the respondents were more concerned with financial risks than accounting policies and alternative accounting treatments, and they seemed to be more confident in their ability to monitor risk. There was also some evidence that AC members were directly involved not only in the monitoring process but also in the design of the risk-reporting systems. Some respondents were fairly confident in their ability to monitor financial risk and described the models they built or used in their work. Others, however, were more skeptical about their ability to grasp all the possible risks and noted that systematic risk was something that could, to some degree, be monitored at a relatively low cost. Again, one respondent suggested that the oversight of financial risks comes from the external auditor, who was also responsible for the preparation of a monitoring report. As one respondent described:

Participant 1:

There are two types of risk: systematic and unsystematic. I will not be able to say anything about unsystematic risk, except that it may happen. We are more concerned with systematic risk, and this is what we can better control and eliminate. We set a gold standard, silver standard or brown standard. But what we really want to have is a red flag system to signal that something is wrong, although we are unable to prevent more substantial unusual events.

The interviews confirmed AC participation in the selection of external auditors. However, their involvement and activity in this process varied. In practice, the requirement to exclude management from the process of selecting an external auditor was not fully met, and management frequently and actively participated in both the search for and selection of an auditor. The letter of inquiry was typically sent at the request of the AC by the company’s administrative department, which handled the affairs of the committee. The tenders for auditing services were submitted to management’s administrative department (or other administrative department of the company) and analyzed there. Management often actively participated in the process of assessing the tenders and in elaborating a short list of potential auditing companies, which was later presented to the members of the AC. Subsequently, the AC short list of potential auditing companies was then presented for approval at a meeting of the supervisory board.

Some of the respondents briefly presented the issues related to selecting an independent auditor.

Participant 6:

The management searches for an external auditor. The AC is not involved in this process. Naturally, we can suggest during the meeting: “Do not take company X, take company Y”.

Others confirmed the involvement of management in the process of selecting an independent auditor, but they also noted that certain solutions were applied that were supposed to create awareness among all the actors in the process regarding who was responsible for the choice of the auditor.

Participant 16:

…the general idea is to, where possible, always emphasize and create the awareness, both on the side of the management and of the auditing company or candidate for auditing company, that it is the supervisory board, which is represented by the AC, who hires the auditing company and not the management. There are subtle ways of doing this, for example, the letter of invitation to tender. This letter may be signed by the CEO, but the letter itself emphasizes that it is on behalf of the AC that the invitation is sent and that the meeting will be held with the AC. We collect the tenders, make a short list, meet with the companies on this list, negotiate the terms and conditions, formulate recommendations and then go to the supervisory board, who makes the final choice.

Further analysis confirmed the participation of management in the selection process. In half of the analyzed cases, the AC had not even met with the representatives of the auditing companies before making the decision to recommend a given auditing company to the supervisory board. In only one case did the AC meet twice with the potential auditors; in the other cases, they only met once. In most cases, management representatives took part in these meetings. Most of the respondents did not see anything wrong with the management actively participating in the selection process. Some even emphasized that this participation is necessary because management would be collaborating with the independent auditor on a daily basis, which is why it was important that there be a “good vibe” between the auditor and the management. Notably, this asymmetry of authority, with significant management control in the selection of an external auditor, has also been documented in the Anglo-American context (Humphrey and Moizer 1990; Gendron and Bédard 2006; Cohen et al. 2010; Fiolleau et al. 2013).

Participant 9:

The entire procedure is rather burdensome from the point of view of a member of the AC, who works full-time somewhere and who needs to spend the entire day at the company to listen to one-and-a-half-hour long presentations of the successive companies of the Big Four, which are really all the same, only trying to capture the subtle differences, which might in the end become the deciding factor. This is tiring and tedious. Subsequently, we discuss the options, taking into account the opinion of the management, of course. After all, it is the management that will be working with the auditor on a daily basis, not me. In such a case, the human factors also play an important role.

The analysis of the criteria taken into account when selecting an independent auditor was also notable. In the opinion of the respondents, the most important factor was the reputation of the auditing company, followed by the level of experience in the given industry and the price of the service. Reputation was usually identified with the auditing companies of the “Big Four.”

Participant 1:

…It is reputation that matters. We do not care about experience in the industry because every auditing firm has the same industry experience. In other words, if you take someone from the Big Four, they will have industry experience because there is industry experience in the world; and if they don’t, they will buy the necessary experience.

In only one case did the AC use a formal tool in the process of selecting an independent auditor. The other respondents admitted to the lack of such tools but indicated that they had plans to create an assessment tool of auditor candidates in the future.

The respondents noticed a recent (and significant) change in the practice of external and internal auditor oversight. Because auditors demonstrated a more active attitude, the AC was also compelled to increase its activity.

Participant 15:

…This is also changing. Previously, the board did not meet with the auditor at all. Only later, when the report was submitted, did the board meet with the auditor. So the auditor would present the report and say that he has no objections. So generally there was no reason to meet with the auditors because they always wrote the same thing, i.e., that they have no objections and that they do not take any responsibility. However, in the last two, three, four years, auditors have started to be more active and write all types of things. Consequently, the AC meets more often with the auditor now and they discuss different matters.

However, raising the requirements with respect to the role of the AC in an effective oversight system (which was enforced by, among other things, introducing regulations related to the responsibility of the supervisory board members for financial reporting) is an adequate mechanism for increasing the motivation and activity of the AC. Most of the respondents confirmed that there was continuous collaboration with the independent auditor and that the auditor was present during all meetings of the AC. In addition, the form of communication with the auditor has become increasingly important. ACs expected comprehensive and prompt communication on the relevant threats and risks to the company.

Participant 7:

The most important thing is that the auditor immediately and directly communicates all his suspicions of any irregularities or threats. Such a direct form of communication with the AC is very important. We want to make sure that all the threats will be communicated immediately after identifying them and that they will be communicated directly. Previously, we dealt with different situations. Any objections were usually formulated on the twentieth page and in small print. Taught by experience, we have decided that we want to have an auditor who will place such things on the first page.

The scope of the information presented also changed. In some cases, standard reports were elaborated, but in others, the AC requested detailed information. The scope of the information the auditors had to prepare varied, depending on the current needs and discussed issues during the AC’s meetings.

Participant 14:

It is obvious that this is a learning process for the auditors as well. In other words, until recently, they were not able to state anything else than what was written on the first page. When asked about, e.g., benchmarking, comparison, they did not have a clue what they were asked. I asked one of our auditors a question like that during a meeting of the supervisory board. I asked about benchmarking, to present our position in the industry. The auditor responded calmly that this does not fall within the scope of his tasks. He was right. However, currently such a requirement does exist and more and more supervisory boards ask the question: what does that really mean? Ok, we have such numbers, but how does that translate into our position within the industry? What is our position with respect to global benchmarks?

The increasing demands with respect to the quantity and quality of information that is presented to the AC form the basis for redefining the contacts with the independent auditor. More wide-ranging questions can now be asked: “What is the essence of the involvement of an independent auditor in the process of investigating a company?” and “Does the investigation contract also include delivering additional information upon the request of the AC?” Undoubtedly, increasing the expectations regarding the scope of the information provided creates a conflict of interests. If the additional information is delivered within the scope of the standard service provided by the auditor, this will cause the auditor to eventually protest (assuming that the fee for the service does not take into account such additional tasks). However, this can also directly cause an increase in the value of the additional service provided outside the scope of the audit and can change the income structure of the auditing company, which, in turn, may cause a greater reliance of auditing companies on additional forms of services and make them less independent. This is a relatively new phenomenon, so it is difficult in the current situation to assess the potential threat to the independence of the auditor. However, this phenomenon does need to be observed and analyzed.

A different picture can be drawn when analyzing the oversight of the internal control. Internal control is considered by many respondents to be the domain of the management board. Therefore, contacts with the internal auditors are rarer than in the case of external auditors and are performed primarily on a case-by-case or irregular basis. In only two cases did the respondents confirm meeting with an internal auditor (or the oversight of internal control) on a regular basis. In two other cases, the AC was not meeting with the internal auditor at all. All the respondents expressed the delicacy of not placing the internal auditor in an uncomfortable situation of “being forced to spy on their employer—the management board.”

Participant 1:

This is a very recent issue. It started just this year. We met the internal auditor, we agreed on the analysis of the control procedures and the internal audit. But we are still discussing how we are supposed to cooperate with the internal auditor. How do we ask a simple question? Shall we meet without the management present? It is obvious that we should meet the auditor alone, but how we do this is not so clear. If we meet without the management, the internal auditor can be treated as an internal cheater. This is a very delicate matter and this issue is on our agenda at this moment. But the AC will have to meet with the internal auditor and internal control and better understand their role in the organization.

The AC typically met with an internal auditor in the presence of the management board; however, in some cases they also had the option to meet without the board. The oversight can also be described as fragmentary. Only one respondent stated that the analysis and control of post-audit activities were analyzed on a regular basis. In most cases, the AC relied on the judgment of the external auditor or did not oversee the internal control at all.

5.2 Resources to perform the oversight of financial reporting and external auditors (Q2)

The literature on the effectiveness of ACs stresses the importance of adequate resources and the presence of independent members on the committee (DeZoort et al. 2002; Cohen et al. 2010).

This study also reveals that AC resources varied across different companies. In the case of larger companies and for those with a foreign investor as a dominant shareholder, the ACs generally enjoyed more resources than other companies. However, in both types of companies, financial literacy and financial expertise were considered the most critical factors affecting the efficiency of AC oversight and monitoring duties.

Although independence is a relatively new concept in the Polish capital market, it is considered an important factor by AC members. However, the interviews revealed that the understanding of the meaning of independence in Poland is slightly different from the EU definition and the charters and reports. The respondents stressed independence as a “state of mind,” in which a non-independent AC member can be independent in her/his judgment while simultaneously having the necessary knowledge related to the activities of the company to exercise effective oversight. In that sense, an independent member is someone who is unafraid to ask difficult questions and raise “uncomfortable” issues amid the silence of the other members.

Participant 10:

Generally, shareholders want to have not only an independent member but also an acquiescent member at the same time. Recently, I was interviewed as a candidate for an independent member and I was asked to what degree I would be independent, if I would also be thinking about the interest of the majority shareholder who owns 70 % of the company’s shares. My answer was that I will be completely independent and will not be thinking of their interest at all. A board member, according to the Commercial Code, should think only about the interest of the company and not about the interests of the owners. Let the owners think about his/her interests. We ended up in a long discussion because the panel members did not know what the interest of the company is and how it is different from the interest of the owners. For independent members, it is a matter of the state of mind. It is a very important institution; however, one has to remember the independent member becomes dependent with time. After two terms as an independent member, you become dependent: you like the company, you like the members of the management board, you trust them and you get used to them, and therefore, you become less alert. In my opinion, a rotation of independent board members should be compulsory.

Independence was also often connected with the notion of the knowledge and skills of the AC member. Financial literacy allowed an AC member to know what questions to ask, but independence allowed them to actually ask the questions. As one of the respondents explained:

Participant 7:

We can discuss independence for hours, but in practice it is important if such a member is able to ask difficult questions that all the other members are uncomfortable with. But these questions must be asked to determine the real problem. Without competences, one would not know what question to ask, but without independence, even if one knows what question to ask, one would not verbalize the question.

Another important issue raised by the respondents related to expertise in accounting and finance. The Polish regulation stipulated that at least one AC member should have formal qualifications in accounting and finance. However, the respondents argued that possessing qualifications in accounting and finance was insufficient for the effective oversight of financial matters. They stressed competence in accounting and finance as a precondition, which is consistent with the EU recommendations (Official Journal of the European Union 2005), combined with business experience.

Participant 16:

The EU directive talks about competencies, but the Auditing Act talks about qualifications. Neither of them mention knowledge and skills. In my opinion, competencies are more important than qualifications. Therefore, I try to be liberal in that respect. I focus on the competencies of a candidate, accepting, for instance, undergraduate accounting courses as proof of formal qualifications.

On average, ACs met four times a year, but additional meetings could be scheduled if necessary. In the case of companies with a dominant foreign investor, the average number of meetings was higher. The AC members also communicated between meetings, typically by phone and less frequently by email. The respondents often suggested that the actual number of meetings depended on the involvement of the chair of the committee (one of the respondents initiated 27 AC meetings in one financial year). The agenda was usually set by the chair of the committee; however, the other members of the AC could add additional points to the agenda if necessary. In some cases, a new topic could also be added to the agenda by a member of the management board. In other cases, a new topic could be added by a member of the supervisory board who was not a member of the AC. The scope of the information received before the meeting was different and depended on the size of the company and the availability of other resources. The larger companies with a dominant foreign investor seemed to have more material provided to them before the meeting (in an extreme case, the AC member could have 200 pages to read, with an average of 20–30 pages). The material usually arrived 1 week before the AC meetings, which was considered by many AC members to be too late because it did not allow them sufficient time to become familiar with the content.

Participant 1:

In almost all companies, the information we get is late. This is an old trick, isn’t it? But I do not think it is mean. The truth is that we have too many points on the agenda and the company has a problem with the production of documents on time. In the largest companies, there are a number of people working for the supervisory board. In smaller companies, the management boards are supervising the preparation of the package, and in most cases it is ready 3–4 days before the meeting. So, most of the supervisory board members get familiar with the package on the train travelling to the meeting.

With the limited time they had to analyze pre-meeting packages, the AC members frequently looked for exceptions and contradictory evidence.

5.3 Critical factors affecting the efficiency of AC (Q3)

Both practitioners and the academic literature in the US and the UK have examined the effectiveness of ACs. A variety of characteristics have been considered to influence the effectiveness of AC members. The data revealed that the perceived efficiency of ACs has increased over time and is associated with the power of the AC members.

In general, the respondents agreed that institutions such as board committees (including ACs) add to the efficiency of corporate governance. They stressed that the size of the monitoring body matters because a large supervisory board makes the responsibilities more ambiguous. It can be observed that board sizes are decreasing. As a result of the introduction of new AC regulations, the size of the supervisory board has decreased to 5 members in some cases. This is because of a rule that states that a supervisory board with only 5 members does not necessarily constitute an AC.

In the past, supervisory boards were much larger; a board with 17 members was not uncommon. There were various reasons for such a large size; participation on a board was considered additional income for little responsibility. In many cases, investors treated an offer of participation on the board as a special bonus for a person they considered important or who had an important social network that could be of use. The development of the capital market and the introduction of the new regulations placed serious responsibilities on the supervisory board, making its members as responsible for financial reporting as management. Thus, the size of the board decreased to the number of members who could effectively contribute to its work.

These recent changes, including the requirement of constituting an AC, are considered additional changes that increase the effectiveness of corporate governance. Many respondents believed that the committees, including ACs, could direct their attention to the responsibilities assigned to them and felt greater responsibility for their actions. One of the respondents stated:

Respondent 1

As a separate institution, an AC has more power—perhaps not power per se, but better possibilities and better-assigned responsibilities. The AC members know that they should pay special attention to the finances of the firm and the firm’s financial reporting. This is something that motivates better and harder work because the AC member feels direct responsibility of being a member of the AC. If I feel stronger responsibility, I try to do better job on the one hand, but on the other hand I can have more of a voice in the discussion with the management of the firm.

Although independence was stressed as an important factor in AC effectiveness, it seems that the meaning of independence was understood differently from the regulations. Independence as a “state of mind which allows asking uncomfortable questions” was often stressed, whereas independence in light of the regulatory definition was often associated with insufficient competency in performing the duties of an AC member.

Because the dominant shareholder influenced the choice of supervisory board members to a great extent, the role of an independent member was often played by an academic professor of economics or management who formally met the criteria of the formal definition but could remain a part of the social network of the majority shareholder. This role could also be played by a quasi-professional board member, a professional consultant specializing in accounting or finance (very often with the qualifications of a financial analyst) who earned a living serving on a number of supervisory boards. These members would normally serve on ACs as independent members and simultaneously satisfied the second requirement of having appropriate qualifications in accounting and finance. In general, this was not regarded as a drawback. Academics are generally considered good contributors to an AC, as one respondent explained:

Participant 8:

I think that with the professionalization of the world, the value of people such as those coming from academia, is great. They can still ask an important question. They do not think in a typical way. They do not function well in the world of procedures, but they ask questions which the other AC members would not ask… It is worth stressing that this is also an important place for academics, as it is a place where they can learn about business fairly quickly. On top of the truly difficult and time-demanding work as a AC member, one can see everything, like a microworld from all possible perspectives. One can see the emotional side of business, taking tremendous pride and great vanity in the owners and/or management. You can see everything as a member of the board.

One respondent indicated that an effective AC is a committee that has a broad set of competencies because this level of diversity helps combine different experiences and perceptions to better see the entire picture of the company. AC members with experience in smaller companies (often with a local dominant shareholder) suggested that the efficiency depended to a great extent on the type of shareholding. Without a doubt, competence and independence were considered the most important characteristics, but demanding owners could also affect the overall efficiency of the AC in particular and the board in general.

Many respondents mentioned that a critical success factor for an efficient AC was the power of the chair. One of the respondents stated “a chair is a guardian of effectiveness.” The chair was considered to be the person responsible for the quality of the work performed because the chair sets the agenda, chairs the meeting, gives voice to the members of the AC during the meeting, and decides in some cases on the need for and type of voting. One of the respondents described the chair as someone who should give support to other AC members and who, with the support of a good lawyer, can push things forward.

6 Discussion

As suggested by Gendron (2009:128), a single theory should not be expected to explain the results obtained in a study; in fact, diverse theories can be employed simultaneously to describe a given reality. The literature reveals that researchers have utilized a number of theoretical approaches to study and explain AC practices, such as agency, institutional, and efficiency perspectives (Cohen et al. 2010; Beasley et al. 2009; Spira 1999). A different approach used in other studies was connected with the application of sociological perspectives to study corporate governance and AC practices in particular (Gendron and Bédard 2006).

According to agency theory, the AC is an independent monitor of management. Without a monitor, management may act in their best personal interests and not in the interests of the principals (shareholders) (Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama and Jensen 1983). Thus, the role of the supervisory board and its sub-committees (including an AC) is to independently monitor management to prevent possible opportunistic behavior. Efficiency theory considers organizations as rational actors and points to the gains in effectiveness or efficiency following the adoption of a new practice (Böhm et al. 2013), whereas institutional theory looks at changes in organizational processes over time (Cohen et al. 2002, 2007) and how existing structures fulfill ritualistic roles to help legitimize the interaction among various participants of the organization. In this view, ACs may be coerced into becoming similar through regulation, following the best practice model or by simply mimicking other organizations to enhance their legitimacy (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Cohen et al. 2007). The AC is often ceremonial in nature, with a focus on providing symbolic legitimacy but not necessarily vigilant monitoring (Spira 1999). When the AC plays a more ceremonial role, the external auditor bears a greater responsibility for reliable financial reporting.

The evidence collected in this study allows us to create a picture of audit practices in Poland. It can be observed that some ACs attempt to be effective monitors of management, as suggested by agency theory. These ACs actively oversee the financial reporting of the company and actively monitor the external auditor. They also play a key role in the external auditor selection process. This is particularly true for ACs in companies with foreign investors that hold a majority of company shares. These owners are highly interested in maintaining effective control over their investment. In the case of concentrated ownership, in which the majority of shares are in the hands of management or an entrepreneurial family, there is less need to introduce effective monitoring devices. In these cases, control can be implemented through direct or indirect involvement in company management or control.

However, there are a number of cases in which a major owner who used to be the CEO of a company becomes chair of the supervisory board upon retirement. In these cases, the AC plays a more ceremonial role and can be considered an ineffective tool in the oversight of financial reports and external auditors. In these cases, the AC relies to a great extent on external auditor reports in performing their oversight roles with respect to financial reporting, while leaving the external auditor selection to the management of the company. This is where the institutional theory may be more useful in explaining the reality of an AC’s function. The existence of an AC and its practices in these cases are to a great degree determined by the new regulations that requiring implementation of an AC and where the company wants to comply with the letter of law. The ACs in these instances often mimic the practices of other ACs to enhance their legitimacy. However, the actions taken are frequently intended to be symbolic and are not vigilant monitoring actions.

The gradual change in the processes of ACs and the perceived shift from symbolic legitimacy to effective monitoring (as described by the agency perspective) can also be explained through the lens of efficiency theory (Böhm et al. 2013). Once the AC begins its symbolic oversight and basic procedures are introduced to legitimize it, certain practices may eventually be found useful for monitoring a company’s activities. As a result, a given practice introduced as a result of new regulations or from the example of a different company, may be considered to be useful and value-adding, which will foster better monitoring. The practice may be used to more effectively monitor a company’s management because the actors in corporate governance see additional gains in effectiveness. According to efficiency theory, an intended symbolic process may, with time, become a significant tool of effective monitoring.

The evidence collected with respect to AC effectiveness in the countries characterized by the Anglo-American corporate governance model is mixed. For instance, Spira (1999, 2002) documented a more ceremonial role for the AC in the UK that was based on a study conducted prior to 2002. Other authors noted informal interactions and communications in accomplishing AC objectives (Gendron and Bédard 2006; Turley and Zaman 2007). The most recent study, based on US data (Beasley et al. 2009), suggests that many AC members strive to provide effective monitoring of financial reporting and to avoid serving on a ceremonial AC. The authors conclude that both substantive monitoring and ceremonial actions of ACs can be observed by analyzing AC processes. The authors suggest a shift toward more substantive oversight in the post-SOX era, with variations across different oversight processes. This change can be associated with the pressure of reforms on corporate governance systems, but can also be attributed to the development of AC practices over an extended period of time.

Outside of the Anglo-American corporate governance model, the AC is a relatively new phenomenon that has developed slowly in the post-SOX period due to the global trend of reforming corporate governance systems (Aguilera and Cuervo-Cazurra 2009). Companies with a large percentage of shares owned by foreign investors seem to be examples of effective monitoring, including active and efficient ACs. Foreign investors typically have a direct incentives to develop monitoring devices and have substantial experience in the introduction of monitoring mechanisms to safeguard their interests in subsidiaries. This practice is also observed in the case of ACs, in which the practices have been copied from headquarters. In the case of smaller listed companies with dominant local ownership, the ACs, if they exist, play an informal role in many cases; however, the degree of formality in AC practices typically increases over time.

In general, the interview data indicate that AC processes are informal in nature. However, the respondents stressed that the substance of oversight changed with time and that the processes became more formal. The informality of AC processes can be associated with the stage of development of the corporate governance mechanism, but can also be a signal of the refusal to directly adopt the foreign concept imposed by EU regulations. Because the Polish corporate governance model is characterized by the dominant ownership of large shareholders who enjoy easy access to the company, the need for better investor protection through better financial oversight processes may not be so evident. Conversely, however, minority investors do not have sufficient power to enforce effective monitoring by an AC.

One additional point to consider is the influence of culture on the adoption of a new practice. It is difficult to successfully promote the AC as a necessary mechanism of shareholder protection when the concept is not embedded in the business culture. In fact, ACs are often understood as a costly burden that must be adopted and enforced as a result of global efforts to strengthen corporate governance systems or as a solution enforced by a pan-national regulator. The perception of the role of an AC in the insider model was summarized by a respondent.

Participant 1:

It does not matter if it makes sense or not. This is not important now. This is a legal requirement now. This is a result of all those scandals from recent years. Perhaps in the long run, this may make sense, but in the short run, this is something like “all bark and no bite”. No one is eager to serve on an AC, and only a few of us feel we are professional in performing our duties.

7 Conclusions

This paper contributes to the literature by providing insights into the specific aspects of effectiveness of ACs by focusing on the AC oversight of financial reporting and external auditors in a country that does not follow the Anglo-Saxon model of corporate governance. Polish corporate governance is characterized as an “insider” model of corporate governance with a high concentration of ownership.

An in-depth analysis of the AC oversight processes indicates that development of ACs and of the processes of forming relations and collaborations between ACs and external auditors remains in an early phase. In the companies investigated, a range of practices may be observed from a merely formal involvement of the AC in the supervision of the reporting process and the work of independent auditors that sometimes has moved toward a more professional approach. This characterization, however, greatly depends on the size of the organizations and the type of ownership.

Our study also illustrates that the current practice has difficulties maintaining the development of corporate governance regulations, particularly those related to ACs. The codification of the law mandating ACs is common in developed capital markets and represents a milestone in the convergence of corporate governance systems in Europe and on a global scale. However, this solution constitutes a challenge for the economy in Poland because the corporate governance system is, to a great extent, shaped by historical and cultural determinants, in addition to the development level of the capital market. It should also be noted that previous studies show that experiences with ACs vary from country to country, but in none of these cases do the committees fulfill the hopes that are invested in them; however, there is evidence that ACs are shifting from a mostly ceremonial nature toward the actual oversight of external auditors and financial reporting.

For ACs to efficiently perform their responsibilities, they must have access to greater resources, including organizational resources that would provide them with a greater degree of independence in performing the functions entrusted to them. The quality of the human resources is also important. Those who are exercising control over the auditor should have adequate knowledge, experience and skills in the fields of accounting, financial auditing and finance. It is also important that the auditor respects the expertise of the AC members. Moreover, AC members should realize that supervision of the reporting and auditing process should not be treated on an ad hoc basis but should typically occur for several hours four times a year. Perhaps as a result of the increased expectations with respect to the tasks performed by members of the AC, it should be expected that a group of quasi-professional AC members will be form who will be able to ask the right questions and quickly pick up on inaccuracies. In this way, the transfer of knowledge regarding the financial situation of a company will not be one-sided.

Additional research into AC practices might shed more light on the development of these practices over time. This paper does not provide information on the involvement of ACs in the monitoring of internal auditors or on the broad set of risks companies face. Another avenue of exploring AC practices might be the sociological perspective, including the ways ACs use different types of expertise to efficiently perform their duties, how AC members develop trust in the various participants of a corporation, and how AC members reduce discomfort connected with the performance of oversight and monitoring responsibilities.

Notes

The 2002 and 2005 Codes recommended that half the supervisory board’s members be independent. Because this recommendation is the most frequently rejected rule by companies, the 2008 amendment in the CGC introduced a requirement of at least two independent board members. With respect to independence criteria, the board is supposed to use the EU Directive as of February 15, 2005.

Of the 368 listed companies, only 230 submitted their compliance reports to the WSE in 2008 (Smardz 2008). The most common forms of non-compliance in the area of good practices of supervisory boards include rules to form an AC, to publish information on corporate websites, and to carry out a self-evaluation of the supervisory boards (Kuchenbeker 2008).

The Corporate Governance Code presents a weak form of implementing corporate governance standards by adopting the “comply or explain” rule as recommended by the Cadbury Report. Under this rule, companies must file a compliance report with the specific corporate governance principles or explain the extent of the non-compliance with corporate governance principle(s).

References

AC Institute. (2004). Exploring Expectations of AC Effectiveness (Fall). KPMG Audit Committee Roundtable Series.

Aguilera, R. V., & Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2009). Codes of good governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(3), 376–387.

Aguilera, R. V., Filatotchev, I., & Jackson, H. G. (2008). An organizational approach to comparative corporate governance: Costs, contingencies, and complementarities. Organization Science, 19(3), 475–492.

Ahrens, T., & Chapman, C. S. (2006). Doing qualitative field research in management accounting: Positioning data to contribute to theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(8), 819–841.

Ahrens, T., & Dent, J. (1998). Accounting and organisations: Realising the richness of field study research. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 10(1), 1–39.

Al-Twoijry, A. A. M., Brierley, J. A., & Gwiliam, D. R. (2002). An examination of the role of ACs in the Saudi Arabian corporate sector. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 10(4), 288–296.

Aluchna, M. (2007). Mechanizmy Corporate Governance w Spółkach Giełdowych. Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH.

Aluchna, M., & Koładkiewicz, I. (2010). Polish corporate governance—The case of small and medium sized companies. International Journal of Banking, Finance and Accounting, 2(3), 218–235.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (2005). Management overrsight of internal controls: The Achilles’ heel of fraud prevention. New York, NY: AICPA.

Auditing Standard Board. (1988). Communication with Auditing Committee. AICPA.

Beasley, M., Carcello, J., Hermanson, D., & Neal, T. L. (2009). The AC oversight process. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(1), 65–122.

Bedard, J., & Gendron, Y. (2010). Strenthening the financial reporting system: Can audit committees deliver? International Journal of Auditing, 14(2), 13–35.

Berglof, E., & Sarmistha, P. (2007). Symposium on corporate governance. Economics in Transition, 15(3), 429–432.

Beasley, M., & Solterio, S. (2001). The relationship between board characteristics and voluntary improvements in AC composition and experience. Contemporary Accounting Research, 18(4), 539–570.

Blue Ribbon Committee (BRC). (1999). Report and recommendations of the Blue Ribbon Committee on improving the effectiveness of corporate audit committee. Stamford, CT: Blue Ribbon.

Böhm, F., Bollen, L. H., & Hassink, H. F. (2013). Spotlight on the design of European ACs: A comparative descriptive study. International Journal of Auditing, 17(2), 138–161.

Burchell, S. C., Clubb, C., Hopwood, A., & Nahapiet, J. (1980). The role of accounting in organizations and society. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(7), 663–685.

Carcello, J., & Neal, T. L. (2000). AC composition and auditor reporting. The Accounting Review, 75(4), 453–468.

Carcello, J. V., Hermanson, D. H., & Neal, T. L. (2002). Disclosures in AC charters and reports. Accounting Horizons, 16(4), 291–304.

Carello, J., Hermanson, D. R., & Ye, Z. (2011). Corporate governance research in accounting and auditing: Insights, practice, implications, future research directions. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(3), 1–31.

Cohen, J. R., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. M. (2002). Corporate governance and the audit process. Contemporary Accounting Research, 19(4), 573–594.

Cohen, J. R., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. M. (2004). The corporate governance mosaic and financial reporting quality. Journal of Accounting Literature, 23, 87–152.

Cohen, J. R., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. M. (2007). The impact of roles of the board on auditors’ risk assessments and program planning decisions. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 26(1), 91–112.

Cohen, J. R., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. M. (2010). Corporate governance in the post Sarbanes–Oxley era: Auditor experiences. Contemporary Accounting Research, 27(3), 751–786.

Collier, P., & Zaman, M. (2005). Convergence in European corporate governance; the AC concept. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 13(6), 753–768.

Committee of Corporate Governance Final Report, (Hampel Report). (1997). Gee and Co. Ltd.

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, COSO. (1992). Internal Control—Integrated Framework. COSO, New York.

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, COSO. (1994). Internal Control—Integrated Framework. The Addendum, COSO, New York.

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, COSO II. (2004). Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework. COSO, New York.

Confederation of British Industry (CBI). (1998). Study group on directors’ remuneration (Greenbury Report).

Cooper, D. J., & Morgan, W. (2008). Case study research in accounting. Accounting Horizons, 22(2), 159–178.

DeZoort, F. T. (1997). An investigation of ACs’ oversight responsibilities. Abacus, 33(2), 208–227.

DeZoort, F. T., & Salterio, S. E. (2001). The effects of corporate governance experience and financial-reporting and audit knowledge on AC members’ judgments. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 20(2), 31–47.

DeZoort, F. T., Hermanson, D. R., Archambeault, D. S., & Reed, S. A. (2002). AC effectiveness: A synthesis of the empirical AC literature. Journal of Accounting Literature, 21(1), 38–75.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron case revisited. Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.