Abstract

This study investigates the financial performance of Dutch companies both with and without women on their boards. The analysis extends earlier methods used in research by Catalyst (The bottom line: corporate performance and women’s representation on boards, 2007) and McKinsey (Women matter. Gender diversity, a corporate performance driver. McKinsey & Company, USA, 2007), two studies that are often cited in the literature, although, each has a number of methodological shortcomings. This article adds to the international debate, which is often normative, through examining 99 listed companies in the Dutch Female Board Index. Our results show that firms with women directors perform better than those without women on their boards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The subject of women on boards of directors is a growing area of research. Scholars (e.g. Adams and Ferreira 2004; Burgess and Tharenou 2002; Van Ees et al. 2007; Sealy et al. 2007), professionals (e.g. McKinsey 2007) and societal pressure groups (e.g. Catalyst 2007) contribute to research on the subject indicating that the representation of women in the boardroom should be higher, and fewer all-male boards should occur for several reasons. Some authors (Brammer et al. 2007) look at the connection between the presence of women at the top and (good) corporate governance: a homogeneous group of directors does not accurately reflect the society in which it operates, and is both a symptom of weak corporate governance and a missed opportunity.

The present article investigates whether or not companies with female directors perform better than companies with no female directors. Firstly, an outline is given of the arguments in favor of diversity from both the economic and the moral perspective, and the hypothesis of the relationship with company performance. The focus then turns to the research by Catalyst (2007) and McKinsey (2007) into the relationship between diversity and the financial performance of a company. The media and opinion makers often refer to these reports, despite their (statistical) shortcomings. This study reflects on and improves the methods of Catalyst (2007) and McKinsey (2007), and in doing so contributes to the discussion.

The empirical investigation in this study uses Dutch data. Companies in the Netherlands use a two-tier board model: the executive board and the supervisory board are two separately functioning boards. Internationally the one-tier model is more usual; the executive and non-executive directors are together within one board of directors). To avoid confusion, this study adopts the international terminology, and refers to the executive board and supervisory board together as the “board”.

In The Netherlands the proportion of women on corporate boards is still very low. The Dutch Female Board Index 2007 shows for the first time in the Netherlands which Dutch listed companies had a woman in one of these two board-tiers; this index ranks firms according to the percentage of women on the board (Lückerath-Rovers 2008). At the end of 2007, 5% of all executive and non-executive directors in Dutch companies were female; this proportion was the weighted average of 2.1% female executive directors and 6.9% female non-executive directors. The absence of women on boards of directors and supervisory boards resulted in a motion put to the Lower House of the Dutch Parliament (Parliamentary Paper 31083, p. 17) to include a target for the proportion of women on the supervisory board in the Dutch Corporate Governance Code. Although, the Corporate Governance Monitoring Committee (Frijns Committee) acknowledged the importance of diversity, it did not include any targets in its recommendations of December 2008. The Committee proposed that the Dutch Corporate Governance Code should include the objective that a company must “aim for a diverse composition in terms of such factors as gender and age” and that each company should establish its own target. The new Dutch Corporate Governance Code from January 2009 includes this objective. A comparison with four other European Corporate Governance Codes (Lückerath-Rovers 2010) showed that France, Germany and the UK also do not include demographic characteristics of directors (including gender) in their corporate governance codes. In Spain, however, both a law is installed that obliges companies to adopt a more balanced composition of the board as the corporate governance code especially addresses the issue. The Spanish law indicates that “balanced” means that each sex should account for at least 40% of the board. The law provides for preferential treatment in the awarding of public contracts for companies that reach this target. The penalty in Spain seems less severe than in Norway (in Norway, a company can be closed down as a last resort), but it certainly has a compelling character.

2 Diversity and corporate governance

Van der Walt and Ingley (2003) describe diversity in the context of corporate governance as the composition of the board and the combination of the different qualities, characteristics and expertise of the individual members in relation to decision-making and other processes within the board. The gender of the board members is therefore only one of the characteristics of diversity. However, this article focuses only on gender forseveral reasons. Firstly, the (normative) debate focuses on gender in the boardroom resulting in quota-legislation in several countries (Norway, Spain, France and the Netherlands). Secondly, gender is the most easy distinguished demographic characteristic compared with age, nationality, education or cultural background, for example. Finally, our study aims to improve the methodology of the popular studies of McKinsey’s (2007) and Catalyst’s (2007) popular studies which also focus on gender.

Whether the presence of women on the board improves the governance of a company is linked to the question of what good corporate governance should achieve. For example, Brown et al. (2002) argue that if good corporate governance does not result in improved performance, then the question of who sits on the board of the company or how that board operates has no practical value, and appointing women to the board then has merely symbolic value. Research into the presence of women on the board is directly connected with other aspects of corporate governance. These include the importance of a good relationship with stakeholders, as proposed by both stakeholder theory (Donaldson and Davis 1991) and resource dependence theory (Pfeffer and Salancik (1978); diversity as a measure of independence as advocated in agency theory [Jensen and Meckling (1976)]; and diversity as a necessity for fair and transparent decision-making Luoma and Goodstein (1999). Huse (2007) found that in Norway, where 40% of all directors are required by law to be female, the gender debate has contributed more to the evaluation of the role and position of the board than any other recent discussion, including shareholder activism or the development of best practices.

Resource dependence theory regards corporate boards as an essential link between the company and its environment and the external resources on which a company depends. This link is necessary for good corporate performance. Using the board of directors as a linkage mechanism with stakeholders provides companies with at least four benefits (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978, p. 145): firstly, linkage may provide the organisation with useful information, secondly, linkage provides a channel for communication purposes, thirdly, linkage is an important step in obtaining commitments of support from important elements of the environment and fourthly, linkage has a value in legitimizing organisations. Hillman et al. (2007) investigated organizational characteristics to determine which of these affect the likelihood of women being appointed. Using resource dependency theory as a basis, they investigated how boards of directors serve as a linkage instrument and under which organizational characteristics gender diversity is most valuable.

By recruiting female directors, companies may provide these benefits from linking with their stakeholders. However, providing legitimacy is especially mentioned in literature on gender diversity in the boardroom. Female directors on boards can provide a valuable form of legitimacy in the eyes of potential and current employees, and women directors also symbolise career possibilities to prospective recruits (Hillman et al. 2007; Singh and Vinnicombe 2004). A board of directors provides legitimacy with regard to several groups of stakeholders. As discussed by Brammer et al. (2007), greater equality of representation relates to direct and indirect benefits that may potentially arise from more closely reflecting the demographic characteristics of key stakeholder groups such as customers, employees and investors. Furthermore, customer-oriented businesses are more inclined to appoint female directors to their board, as such appointments give these businesses legitimacy with regard to their customers and enhances relations with customer stakeholders (Brammer et al. 2007). Also, such businesses show that ‘they are responding to calls for increased diversity for better governance and better use of available talent’ (Singh 2007, p. 2131). This might enhance their reputation and consequently their performance. Hillman et al. (2007) add that legitimacy and conformity to societal expectations are considered key components of organisational survival.

Adams and Ferreira (2004, p. 14) suggest that gender diversity on boards may have a political dimension. ‘Companies may care more about diversity when they are concerned about their public image, either because they are large firms which are visible to outsiders or because they are required to deal with government agencies which have preferences for diversity’. Large organisations are more likely to be a visible target for the demands of others in the social context and thus need to establish linking in the social context (Hillman et al. 2007, p. 944; Pfeffer and Salancik 1978, p.168) Indeed company size is one of the most consistent predictors of a company having female directors, according to Burgess and Tharenou (2002).

Can demographic characteristics of directors actually have so much impact on the organization that its performance improves? Finkelstein and Hambrick (1996) suggest two reasons why the composition of the board might affect the performance of a firm. Firstly, the board has the most influence on a company’s strategic decision-making. Secondly, the board also has a supervisory role, in that it represents the shareholders, must respond appropriately to takeover threats, and monitors the total value of the company. Given that individual board members jointly determine decision-making within the board, the composition of the board can affect the performance of a company. However, when researching the effect of the composition of the board, several complicating factors may arise. These complicating factors include firstly, how to measure diversity over time, secondly, causality between diversity and performance, and thirdly, critical mass theory. In the next section, which addresses previous research on the relationship between gender diversity and firm performance, we will further elaborate on these issues.

Recent literature suggests various arguments as to why the greater representation of women on boards results in better decision-making within the boardroom. The presence of women might improve team performance, because more diverse teams may consider a greater range of perspectives and therefore reach better decisions. These better decisions then ultimately could lead to higher business value and business performance (Burgess and Tharenou 2002; Singh and Vinnicombe 2004; Carter et al. 2003). Failure to choose the most suitable candidate affects company performance and the absence of women might be suboptimal for the firm. Brammer et al. (2007) argue that, if we assume that certain valuable qualities are not evenly distributed among demographic groups (men and women), the company is structurally denying these qualities by excluding women from decision-making positions. Companies with a higher degree of diversity on the board also give an important positive signal to (potential) employees of that company. The competitive situation both inside and outside the company (between existing and potential employees) is strengthened (Rose 2007), and performance should improve (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). Society also regards a higher degree of diversity as positive, and the reputation of the company improves. When the diversity within the company and its management reflects the diversity within the relevant market, a company is better able to serve and retain that market (Carter et al. 2003; Pfeffer and Salancik 1978; Donaldson and Davis 1991).

Diversity might also contribute to the discussion, exchange of ideas and performance of the group (Kang et al. 2007). On the other hand, however, taking into account a wider range of more perspectives can also be more time-consuming and result in more conflicts. Weighing up more perspectives can delay decision-making and may eventually make the board more divided than a less heterogeneous board would be (Rose 2007). Such behavior has been observed among diverse top management teams which can be more expensive and difficult to coordinate than homogeneous teams, and where the increased costs from lack of coordination can neutralise the increase in financial performance (Dwyer et al. 2003).

3 Research on diversity and company performance

The media and opinion makers regularly report that diversity on the board leads to higher performance (the so-called business case). The studies by consultancy firm McKinsey (2007) and non-profit organization Catalyst (2007) offer support for this positive relationship. However, methodological weaknesses fundamentally flaw both studies. For example, neither study indicates whether or not the differences in the performance measures are statistically significant and the selection of companies in the McKinsey report is based on subjective criteria (which will be described more in detail in the next section).

The results of other (empirical) studies of the relationship between diversity and business performance are also not consistent. Some studies have found a positive relationship between diversity and financial performance, while others have found no relationship or even a negative relationship (Rose 2007; Van Ees et al. 2007). For example, Krishnan and Park (2005) examined the relationship between diversity and return on total assets for 679 companies from the Fortune 1,000 data base. The results showed a positive relationship between diversity in management teams and financial performance. Carter et al. (2003) looked at the relationship between Tobin’s Q and the presence of women in the boards of the Fortune 1,000 companies and also found a statistically significant positive relationship. On the other hand Rose (2007) did not find a relationship between board diversity and Tobin’s Q for Danish listed companies.

It seems that research into the business case is complicated by several factors. Here we consider three of the most commonly discussed of these: time, causality and critical mass. Firstly, diversity can be measured as the number of women at a certain moment in time (a static measure) or as the change in the number of women on the board (a more dynamic measure) and the consequences of that change (Ryan and Haslam 2005). In 2003 The Times Footnote 1 reported that listed companies in the United Kingdom would probably be better off without women on the board. The author found a negative relationship between performance and companies at the top of the English Female FTSE100 Index 2003. Ryan and Haslam (2005) responded by criticizing the short-sightedness of the article. Ryan and Haslam (2005) investigated appointments of men and women to the board in relation to financial performance. They found that the performance of companies that appointed a woman was worse during the 5 months prior to that appointment than the performance of companies that appointed a man. They therefore introduced the term “glass cliff” to indicate that women are sometimes appointed when a company is in trouble. Lee and James (2003) observed a fall in stock prices after the appointment of a new chief executive officer (CEO), and this fall was greater after the appointment of a female CEO. According to Lee and James, an investor associates the appointment of a new CEO with increased uncertainty, and the uncertainty is even greater when that CEO is female. Precisely because the board has an influence on strategic decisions (see Finkelstein and Hambrick 1996) the effects cannot be measured in the short term and this also applies to a changes in the composition of the board.

Secondly, causality and endogeneity may impact conclusions. For example, Van Ees et al. (2007) argued that a more diverse board could arise in times of poor company performance. Shareholders are more likely to intervene in the decisions of top management (i.e. the executive directors) in difficult times, thus increasing the pressure to have more independent (non-executive) directors. Furthermore, if shareholders think that the more homogeneous a board is, the less critical it is likely to be, they may also increase the pressure to have greater diversity in the boardroom to improve this situation. If, later, researchers investigate the relationship between company performance and the appointment of independent board members (in this case: women), a negative rather than positive relationship can be found because the appointment of women directors followed from the poor performance. Adams and Ferreira (2009) provided evidence indicating that the presence of female directors has a positive relationship on board effectiveness, comparable to the impact oft independent directors. For example, they found that female directors have better attendance records than male directors, male directors display fewer attendance problems the more gender-diverse is the board, and women are more likely to join monitoring committees. However, they also found that the impact of these efforts on performance is positive for companies with previously weak governance, but negative for companies with an already strong governance structure. They suggest that this negative effect might be caused by the effect of over-monitoring in those companies.

Lastly, a complicating factor in investigating the impact of diversity on company performance comes from critical mass theory. This theory suggests that only when a certain threshold is reached (a critical mass) the impact of a subgroup (such as ‘women on the board’) becomes more pronounced (Kramer et al. 2006). Kramer et al. (2006, p. 53) argue that ‘a board with three or more women is more likely to experience the positive effects and contributions to good governance than a board with fewer women.’ According to Kanter (1977), being the only one with certain demographic characteristics can lead to tokenism. Tokens are considered to represent an entire demographic group (women) and are seen by the dominant group (men) as a stereotype. The stereotypical female director or supervisor can be expected to reflect characteristics and opinions of all women, rather than her own individual characteristics and opinions. Based on critical mass, research into the relationship between female directors and performance might require a distinction between boards with one woman and boards that have reached a certain threshold.

Catalyst (2007) and McKinsey (2007) pay little attention to these complicating factors, nor do they perform statistical tests of the significance of their results. However, given the popularity of the Catalyst and McKinsey research and their specific approach in categorising companies’ boards as diverse or non-diverse, for consistency and for pusposes of comparison we apply their methods to our study of listed companies in the Netherlands, but with improvements aimed at statistical weaknesses in their studies. These improvements include statistical significance tests within the univariate analyses and the addition of a multivariate regression analysis. The goal of our study is therefore twofold: firstly, to critical evaluate these two often cited studies and secondly, to investigate the relationship between women directors and company performance in the Netherlands.

4 The Catalyst (2007) and McKinsey (2007) studies

4.1 The Catalyst (2007) report

Catalyst (2007) examines the relationship between women on corporate boards and their companies’ financial performance in the United States. Catalyst ranked 520 companies according to the average percentage of women on those companies’ boards in 2001 and 2003 and divided the companies into four quartiles, each comprising 130 companies. The study compares the financial performance of companies in the top quartile (those companies with the highest percentage of women on their boards) with that of the bottom quartile (companies with the lowest percentage of women on their boards). The financial measures used by Catalyst were return on equity (ROE), return on sales (ROS) and return on invested capital (ROIC). Figure 1 shows the differences in the averages of the financial performance measures between the firms in the bottom quartile and the top quartile.

Results of Catalyst (2007)

Figure 1 shows that the financial performance of the top quartile is at least 41% higher (based on ROS) than that of the bottom quartile and is even higher (64%) for ROIC. Catalyst reported neither on statistical significance regardingthe differences, nor on whether or not extreme values were taken into account, which would affect the accuracy of the averages for the two groups of companies. Lee mentioned (in a footnote) that the correlation between the presence of women on the board and financial performance does not necessarily imply a causal relationship between these two variables.

4.2 The McKinsey (2007) report

The McKinsey Report (“Women Matter” 2007) consists of two studies (one a qualitative and the other a quantitative study) of the relationship between women in top management teams and firm performance. The qualitative investigation was a large-scale survey of 115,000 employees, inquiring into why companies with women at the top might perform better than companies with no women in top management teams. However, media attention focuses mainly on the quantitative investigation in the report. The McKinsey (2007) study is a collaboration with the Swiss company, AMM Finance, and its Amazone Euro Fund (AEF). The study compares the 89 European listed companies in the AMM/AEF data base with the best diversity score (scored by AMM/AEF) against their industry average. Unlike the Catalyst (2007) investigation, McKinsey (2007) does not compare companies on the basis of the percentage of women on the board, but rather compares the most gender-diversified companies against the average of the entire sector. The financial performance of these companies and the sector in which they operate was measured on the basis of return on equity (ROE), operating result (earnings before interest and taxes, EBIT) and stock price growth. The results showed that ROE was 11% higher for the more diverse companies), EBIT was 91% higher and stock price growth was 36% higher.

4.2.1 Selection of companies?

The McKinsey (2007) report includes the 89 companies in the study in collaboration with the Amazone Euro Fund, using three criteria for diversity devoped by AEF: (a) the proportion of female (executive) directors, (b) the presence of more than two female non-executive directors, and (c) the focus on (“special attention to”) diversity in the annual report. However, neither McKinsey (2007) nor AEF defined “specific attention” andthe metrics used to measure this criterion. Moreover, and most important, the companies in the Amazone Euro Fund are selected not only on the basis of these diversity criteria, but also on the basis of past performance. The Amazone Euro Fund flyer states that it uses: “Firstly a gender diversity scoring which has been defined under very strict criteria by ourselves, followed by a financial scoring which allows only the best quality stocks to be selected for the fund.” Given that the McKinsey (2007) results are based on AEF’s selection, which is made on the basis of performance, a bias necessarily occurs.

McKinsey (2007) then compares the results of the 89 companies with the average of their sector. However, the results are aggregated for all sectors together. The McKinsey (2007) report does not indicate which sectors are represented in the group of 89 companies, whether sectors are equally distributed, or how the companies are distributed across sectors or countries. Consequently, the information in the report and the companies concerned are neither verifiable nor is the study replicable. Van Ees et al. (2007) excluded the McKinsey (2007) report from their discussion of research into firm performance and gender diversity, because the report does not specify how the study was set up, which is not in line with the scientific requirement of reproducibility. Similarly, Wielaard and Nierop (2008) concluded that the hard evidence that McKinsey provides about the relationship between firm performance and women in top management is very thin.

5 Methods

5.1 Sample

The sample for our study consists of 116 Dutch companies listed on the Amsterdam Euronext stock exchange on June 30, 2008. Only companies with a statutory domicile in the Netherlands are included in the study, because there are large differences in diversity between countries and using companies with a statutory domicile in another country could affect the results (Lückerath-Rovers and Van Zanten 2008). Listed investment funds are also excluded because of the special nature and management of these companies. Data of sufficient quality for all 3 years in the period 2005–2007 was thus available for 99 companies. Of these 99 companies, 68 companies (69%) have no female directors, and 31 companies (31%) have one or more female directors. Most companies with female directors have only one woman on the board and most of these are non-executive directors (members of the supervisory board) For example in 2007 22 of the 31 companies have one female director, seven have two female directors, one company (TNT) has three female directors and only one company (Ahold) has four female directors on its board. Only six female directors (out of 50) are on the executive board. Due to the limited number of boards with more than one female director testing the critical mass theory is not useful in the context of The Netherlands. The average percentage of female directors for the overall sample of 99 companies is 4.02%, with 12.8% being the average percentage for the 31 companies with female directors.

5.1.1 Measures

Board diversity For this study three possible measures of board diversity could be adopted: the Catalyst (2007) method, the McKinsey (2007) method, and a relative measure.

Catalyst ( 2007 ) method In The Netherlands, Catalyst quartile method is not applicable. The division into four quartiles requires that the quartiles are distinctly different, and that the average percentage of women directors for companies in the list increases gradually from 0 to the maximum of 38% (for Ahold). However, the number of companies in the sample is 99, and 68 of these had no women on the board during the research period. Since each quartile in The Netherlands contains around 25 companies, there would be no distinction between the quartiles: both the first and second quartiles and almost all of the third would have no women on the board. Consequently, as an alternative to the quartile approach, a dummy measure of diversity is used for our study for comparison between companies without women on the board and companies with women on the board during the period 2005–2007.

McKinsey ( 2007 ) method The McKinsey (2007) study compared the performance of 89 companies that scored best on gender score against the average performance of the sector in which these companies operate. Our study compares the performance of the most gender-diversified companies (31 companies with female directors) against the average performance of all companies (and separately for their sector).

Relative diversity measure In addition to the diversity measures described above, a relative diversity measure is also tested in this study. This measure calculates the average proportion of female directors on the boards of the sample companies during the research period (2005–2007). The use of a multi-period average measure allows better control of changes in diversity, increases reliability and also makes the analysis more dynamic (Erhardt et al. 2003; Ryan and Haslam 2005).

Performance Our study uses the same performance measures as Catalyst (2007) and McKinsey (2007). As stated above, the measures used by Catalyst (2007) were return on equity (ROE), return on sales (ROS) and return on invested capital (ROIC), while McKinsey’s (2007) financial performance measures were return on equity (ROE), operating result (EBIT) and stock price growth. As in the McKinsey (2007) study we include total shareholder return (TSR) as a financial measure together with the accounting measures. In addition to stock price growth, TSR includes the dividends paid, thus providing a more complete picture of the return to the shareholder.

Control variables Both Catalyst (2007) and McKinsey (2007) compared means, which involves a univariate analysis, testing one variable at a time. However, they have not controlled for other variables that might interact with the likelihood of female directors being appointed. Some variables, such as board size and firm size, have an impact on this likelihood, if only because of the limited number of seats available. In our study, OLS regression analysis includes both board size and firm size (natural log of total assets) as control variables. It also includes a dummy variable for companies operating in the financial sector, because companies in that sector are on average the largest companies but also have the most female directors (Lückerath-Rovers and Van Zanten 2008).

5.1.2 Comparison of financial ratios

Both the Catalyst (2007) and McKinsey (2007) studies compare the means of several financial ratios of companies with or without female directors but, again,they do not report whether or not the differences are statistically significant. However, even if these statistical tests were performed, it is questionable whether the comparison of means is an appropriate test. Whittington (1980) identified two uses of financial ratios: normative and positive. The normative use is for the measurement of differences in performance, and the positive use is for the estimation of an empirical relationship. The normative use enables a conclusion to be drawn as to whether the financial ratio is high or low compared with the standard. The different statistical models available for the normative (comparative) or positive (predictive) use of financial ratios require different statistical properties in the underlying data. The comparison of means requires that the data have equal intervals, have a normal distribution and show homogeneity of variance. Since financial ratios often do not follow a normal distribution (Barnes 1987) and means are affected by extreme values, our study also applies a median test. Although, the median test is considered to be less powerful, the comparison will not be influenced by extreme values.

5.1.3 Research limitations

Although, a relationship between the presence of women on the board and firm performance can be found, it is more difficult to prove a causal relationship. Hambrick and Mason (1984) note that attention to causality in such research is important, because company characteristics may also affect the composition of the board. For example, a retail company may have more female directors than an oil-and gas company, when considering the gender of employees and customers. More female employees at all levels of a company will probably lead to more women at senior positions, and ultimately, on the board. A company with more female customers may have more incentives to communicate and link effectively with these customers by means of also female employees at all levels (as also suggested by Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) in the Resource Dependency Theory) Moreover, as discussed before, previous studies show that investors do not always respond positively to the appointment of a woman (see Lee and James 2003; Ryan and Haslam 2005; Van Ees et al. 2007).

6 Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for all companies in the sample and also the differences in means and medians between companies with and without female directors. During the period 2005–2007, 31% of the 99 companies had one or more women on the board, and on average 4% of the directors were women. This is the weighted average of 2% female executive directors and 8% female non-executive directors. The average total board (combined executive board and supervisory board) had 7.8 board members: 10.0 for companies with female directors and 6.3 for companies without female directors. The difference in board size is significant (t = 5.4). Firm size is significantly larger for companies with female directors (t = 4.4). Table 1 also shows the differences in means and medians for financial performance. The comparison of means is similar to the Catalyst (2007) approach, and is discussed in the next section.

6.1 Catalyst (2007) method

Figure 2 shows the averages of return on equity (ROE), return on sales (ROS) and return on invested capital (ROIC) for the two groups of companies (with and without female directors). (Figure 2 is derived from Table 2, but displays the information in the same way as the Catalyst (2007) report (see Fig. 1) for ease of comparison).

Using the same variables as used by Catalyst (2007) shows that companies with women directors score, on average, better than companies without women directors. The difference is greatest for ROE: companies with women directors have an average ROE of 23.3% while companies without women directors have an ROE of only 11.1%, which is a significant difference of 110% (t = 4.0). The ROS and ROIC for companies with women directors are, respectively, 17% (t = 1.2) and 54% (t = 2.3) higher than for companies without women directors. The difference in ROIC is significant. Comparison of medians shows similar results although, the difference in ROIC using this measure is no longer significant. Surprisingly the comparison of the means and medians for TSR shows a negative relationship and, while not significant, represents a counter-intuitive result. Moreover, stockprice growth shows a positive (but not significant) relationship, yet paid-out dividends is the only difference from TSR. This couldimply that companies with female directors pay-out relatively lower dividends than companies without female directors. However, determining reasons for this difference would require further research.

6.2 McKinsey (2007) method

Using the McKinsey (2007) approach, the differences between the companies with female directors and the overall average of all companies are shown in Fig. 3.

For the first three performance measures (as used in the McKinsey (2007) approach—which does not compare companies with and without female directors but rather investigates whether companies with female directors perform above the average of all companies) the companies with female directors do indeed perform above the average: ROE is 56% higher than the average for the overall sample, EBIT is 17% higher and stock price growth is 8% higher. However, for the additional financial measure, TSR, the result is slightly lower (−9%) for the companies with female directors. The analyses by sector (not shown) display a similar picture. The t test is not applicable for this comparison. However, on the basis of the correlation coefficients (see Table 2) only the correlation between ROE and the presence of female directors is positive and significant (P < 0.01).

The correlation coefficients also show that the probability of the presence of a woman on the board increases with firm size and board size. Both the presence of a woman on the board (dummy variable) and the percentage of women on the board are significantly and positively correlated with ROE. As with the comparison of means in the previous section, the correlation with TSR is negative but not significant. There is no multi-collinearity between the variables.

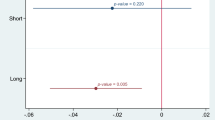

6.3 Regression analysis

In addition to the Catalyst (2007) and McKinsey (2007) methods, this study also uses a regression analysis to further explore the relationship between ROE and the presence of female directors. Table 3 shows the regression analysis with ROE as the dependent variable (models 1–3). Model 1 is the control model, including firm size, board size and a dummy variable for financial companies. In all three models, ROE relates positively to the size of the company and negatively to financial sector. The results in Model 2 show that the presence of one or more female directors on the board relates positively and significantly (t = 3.2) to ROE. The adjusted R 2 increases from 0.18 in Model 1–0.25 in Model 2. The results in Model 3 show that the relative presence of women on the board is related positively and significantly (t = 2.5) with ROE, and the adjusted R 2 increases to 0.22.

A striking result that follows from this study is that higher return on equity is consistently and statistically significantly for companies with women on the board than for companies without women on the board. The regression analysis also shows the presence of women to be a significant variable in relation to ROE. Both results suggest that on average the presence of women on the board is a distinctive feature of companies that perform better. However, the other variables do not show a significant relationship, and for TSR the relationship is negative. However, this study does not suggest that there is causality and would therefore be premature to use this positive relationship as an argument for appointing women to a board.

7 Conclusion

Recent literature assumes that a more diverse board leads to better quality decision-making, as the board is more independent and takes account of more perspectives. However, the impact on the decisions made and subsequently on financial performance is difficult to measure because many factors affect the performance of a company. Causality and cross-linkage between diversity and other performance-influencing factors make single factor research problematic.

Nevertheless, as with the McKinsey (2007) and Catalyst (2007) studies higher ROE in our study is consistently and statistically significant for companies with female directors compared to companies without female directors. However, in The Netherlands the majority of female directors are non-executive directors who are often the only woman in the boardroom. Furthermore, not all performance measures in our study show a significant positive relationship with the presence of women in the board. From these findings it cannot be conclude definitely that one woman on the board impacts the performance of the company on her own. Along with previous empirical studies, our results may ad support to the idea that having women on the board is a logical consequence of a more innovative, modern, and transparent enterprise where all levels of the company achieve high performance (a.o. Singh and Vinnicombe 2004). The results may also support the notion that companies with women on their boards have a better connection with the relevant stakeholders at all levels of the company, which also improves the company’s reputation. This follows from the resource dependency theory, which theory describes the board of directors also serves as a linkage mechanism towards all relevant stakeholders. (see Pfeffer and Salancik 1978; Hillman et al. 2007). Also (female) employees at companies with women on their boards are more motivated to excel because they all see that they can reach the top (Rose 2007). Companies with women on the their board could be more successful because people are promoted on the basis of their capabilities and not on the basis of demographic characteristics (Krishnan and Park 2005) and the companies are more successful in making use of the whole talent pool for competent directors instead of only half of the talent pool. More research is required, however, to discover the reasons behind the better ROE performance and the other elements conjectured above of these specific companies. Other i questions worthy of further investigation include whether or not the women on the board have different management or supervisory styles from their male colleagues on the board, whether or not companies with more women on their boards are also more diversified at other levels, and why the shareholder return does not relate positively to diversity. Results of such may help to shed more light on the cause and effect relationship between diversity and firm performance.

From our study, three furtherr issues are highlighted. Firstly, while this study is based on the percentages of female directors at year-ended 2007, it is worth investigating whether the goal included in the Dutch Corporate Governance Codefrom 2009, to ‘aim for a diverse composition in terms of gender’ has resulted in an increase in the representation of female directors. If so, then other countries might also consider including a similar goal in their Corporate Governance Code. If no substantial progress is made as a result of this measure in the Dutch context, then other more affirmative actions comparable with those taken by Spain or Norway could be considered. Secondly, as mentioned before, the relevant interval before or after the appointment of a woman on the board and the existence of a potential threshold (critical mass) needs to be considered in seeking evidence for building the business case for more women on boards. Finally, the contradiction in the results regarding the relationship between female representation on the board and both stockprice growth and total shareholder return needs further investigation. While the only difference between the results for these two measures is paid-out dividends, this may indicate a difference in attitude between male and female directors towards the shareholders’ and the company’s interests.

Notes

Women on board: Help or hindrance? The Times, 11 November (2003).

References

Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2004). Gender diversity in the boardroom. ECGI working paper series in Finance.

Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94, 291–309.

Barnes, P. (1987). The analysis and use of financial ratios: A review article. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 14, 449–461.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Pavelin, S. (2007). Gender and ethnic diversity among UK corporate boards. Corporate Governance, 15(2), 393–403.

Brown, D. A. H., Brown, D. L., & Anastasopoulos, V. (2002). Women on boards: Not just the right thing…but the “bright” thing. Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada.

Burgess, Z., & Tharenou, P. (2002). Women board directors: Characteristics of the few. Journal of Business Ethics, 37(1), 39–49.

Catalyst. (2007). The bottom line: corporate performance and women’s representation on boards.

Carter, D. A., Simkins, B. J., & Simpson, W. G. (2003). Corporate governance, board diversity and firm value. The Financial Review, 38, 44–53.

Donaldson, L., & Davis, J. H. (1991). Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management, 16(1), 49–64.

Dwyer, S., Richard, O. C., & Chadwick, K. (2003). Gender diversity in management and firm performance: the influence of growth orientation and organizational culture. Journal of Business Research, 56, 1009–1019.

Erhardt, N. L., Werbel, J. D., & Shrader, C. B. (2003). Board of director diversity and firm financial performance. Corporate Governance, 11, 102–111.

Finkelstein, S., & Hambrick, D. (1996). Strategic leadership: Top executives and their effects on organizations. USA: West Publishing Company.

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206.

Hillman, A. J., Shropshire, C., & Canella, A. A. (2007). Organizational predictors of women on corporate boards. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 941–952.

Huse, M. (2007). Boards, governance and value creation. The human side of corporate governance. USA: Wiley.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360.

Judge, E. (2003). Women on board: Help or hindrance? The Times, November 11, page 21.

Kang, H., Cheng, M., & Gray, S. J. (2007). Corporate governance and board composition: Diversity and independence of Australian boards. Corporate Governance, 15(2), 194–207.

Kanter, R. M. (1977) Men and women of the corporation. New York: Basic Books

Kramer, V. W., Konrad, A. M., & Erkut, S. (2006). Critical mass on corporate boards: why three or more women enhance governance, Wellesley centers for women. Report WCW 11.

Krishnan, H. A., & Park, D. (2005). A few good women: On top management teams. Journal of Business Research, 58, 1712–1720.

Lee, P. M., & James, E. H. (2003). She’-E-Os: Gender effects and stock price reactions to the announcements of top executive appointments. Darden business school working paper no. 02–11.

Lückerath-Rovers, M. (2008). De Nederlandse female board index 2007. Analyse van de vrouwelijke bestuurders en commissarissen bij 122 Nederlandse beursondernemingen, Erasmus Instituut Toezicht and Compliance, http://www.toezichtencompliance/publicaties.

Lückerath-Rovers, M. (2010). A comparison of gender diversity in the corporate governance codes of France, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Available at SSRN: http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=1585280, April 6, 2010.

Lückerath-Rovers, M., & van Zanten, M. (2008). Topvrouwen. Wie zijn ze. Waar zitten ze. En: Hoe krijgen we er meer. Academic service, ISBN: 9789052616926, p. 232.

Luoma, P., & Goodstein, J. (1999). Stakeholders and corporate boards: Institutional influences on board composition and structure. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 553–563.

McKinsey & Company. (2007). Women matter. Gender diversity, a corporate performance driver. Paris: McKinsey & Company, Available at: http://www.mckinsey.com/locations/swiss/news_publications/pdf/women_matter_english.pdf.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books.

Rose, C. (2007). Does female board representation influence firm performance? The Danish evidence. Corporate Governance, 15(2), 404–413.

Ryan, M. K., & Haslam, S. A. (2005). The glass cliff: Evidence that women are over-represented in precarious leadership positions. British Journal of Management, 16(2), 81–90.

Sealy, R., Singh, V., & Vinnicombe, S. (2007). The female FTSE report 2007, Cranfield University.

Singh, V. (2007). Ethnic diversity on top corporate board: a resource dependency perspective. International Journal of Human Resources Management, 18(12), 2128–2146.

Singh, V., & Vinnicombe, S. (2004). Why so few women directors in top UK boardrooms? Evidence and theoretical explanations. Corporate Governance, 12(4), 479–489.

Van der Walt, N., & Ingley, C. (2003). Board dynamics and the influence of professional background, gender and ethnic diversity of directors. Corporate Governance, 11(3), 218–234.

Van Ees, H., Hooghiemstra, R. B. H., van der Laan, G., & Veltrop, D. (2007). Diversiteit binnen raden van commissarissen van Nederlandse beursgenoteerde vennootschappen, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen.

Whittington, G. (1980). Some basic properties of accounting ratios. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 7(summer), 219–232

Wielaard, N., & Nierop, T. (2008). Spookcijfer: Vrouwen, winst en McKinsey. De Accountant, Available at: http://www.accountant.nl/Accountant/Actueel/Spookcijfer/Vrouwen+winst+en+McKinsey.aspx, February 7, 2008.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lückerath-Rovers, M. Women on boards and firm performance. J Manag Gov 17, 491–509 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-011-9186-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-011-9186-1