Abstract

Introduction

An unprecedented shortage of infant formula occurred in the United States (U.S.) in 2022 and posed widespread challenges to infant feeding nationwide. The purpose of this study is to investigate mothers’ experiences during the 2022 infant formula shortage and its perceived impacts on infants’ diet and health.

Methods

Mothers (n = 45) of infants under 8 months old from Washington D.C. were invited to participate in a virtual study meeting during the summer of 2022. Mothers completed surveys regarding their demographics, infants’ anthropometrics, infant feeding practices, information they have received about infant feeding, and knowledge about infant feeding practices. They then participated in a qualitative interview about their experiences during the infant formula shortage.

Results

Overarching themes were: the shortage (1) had adverse impacts on mothers’ mental and emotional health; (2) had significant financial and intangible costs; (3) led to changes in infant feeding practices; (4) social and family networks were helpful in navigating the shortage; and (5) mothers felt fortunate to have resources to breastfeed and/or obtain formula.

Discussion

The infant formula shortage adversely impacted mothers’ mental and emotional health, and was costly, in terms of financial and intangible costs. Findings demonstrate the need to develop clinical and policy approaches to support mothers in feeding their infants and provide education about safe infant feeding practices.

Significance

An unprecedented shortage of infant formula occurred in the United States (U.S.) in 2022 and posed widespread challenges to infant feeding nationwide. Findings call attention to concerning impacts of the infant formula shortage on mothers’ mental and emotional health and highlight the disproportionate adverse impacts on Black mothers and mothers from low-income households. Enhanced efforts to connect mothers with resources such as community health workers are needed to support mothers in providing their infants with proper nutrition, particularly during shortages or other unexpected crises that may pose a barrier to infant feeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An unprecedented shortage of infant formula occurred in the United States (U.S.) in 2022. This is alarming because the vast majority of U.S. infants are partially or entirely reliant on infant formula for nutrition, with only one in four infants exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life (United States Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, 2023b). Infants from low-income households are particularly likely to rely on infant formula, and 56% of all U.S. infant formula sold each year is consumed by infants enrolled in the WIC program (United States Department of Agriculture, 2022). Disproportionate reliance on infant formula among mothers enrolled in the WIC program is related to persistent racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in breastfeeding in the U.S. (Jones et al., 2015), which result largely from social determinants including disparities in access to paid maternity leave, lactation support, and breastfeeding education (Standish & Parker, 2022).

The infant formula shortage was caused in part by voluntary recalls of several formulas produced by Abbott Nutrition, the shutdown of an Abbott Nutrition plant in Michigan in February 2022 due to bacterial contamination (United States Food and Drug Administration, 2023), and ongoing supply chain interruptions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic (Calder et al., 2021). Because Abbott is among the largest suppliers of infant formula in the U.S. and produces specialized formulas for infants with severe allergies, gastrointestinal conditions, and metabolic disorders (Choi et al., 2020), access to specialized formulas rapidly diminished early in 2022. This resulted in a lack of appropriate nutrition for infants with these and other health conditions (Abrams & Duggan, 2022). The availability of routine formulas also declined drastically, posing challenges to infant feeding nationwide (Abrams & Duggan, 2022). By May 2022, out-of-stock rates were 74% nationally (Paris, 2022) and 82.4% in Washington, D.C. (“What You Need To Know About the Baby Formula Shortage,” 2022). The purpose of this qualitative study was to investigate mothers’ experiences during the infant formula shortage and examine perceived impacts of the shortage on infants’ diet and health. We also examined mothers’ sources of information about infant formula and their knowledge about the safety of alternative approaches for infant feeding during the shortage.

Methods

Recruitment and Sample

Mothers were recruited from Washington D.C. between June 2022 and August 2022 using community listservs and social media groups. Interested mothers were contacted by the research team to determine study eligibility. Inclusion criteria were (1) residing in Washington D.C. and (2) having a child less than 8 months old. The age range of up to eight months was selected to include both younger infants who were likely only consuming breast milk and/or formula as well as older infants who had been introduced to solid foods. This was intended to allow us to explore if mothers had increased the amount of or accelerated the introduction of complementary foods and/or cow’s milk relative to the recommended ages of 4–6 months and 12 months, respectively.

Mothers were recruited through convenience sampling and those who initially enrolled in the study were predominantly highly educated and non-Hispanic white. Therefore, eligibility for SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) and/or WIC (Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children) and/or identifying as Black/African American or Hispanic/Latino, were added as inclusion criterion in mid-July 2022 to enroll a more diverse sample of mothers. Neighborhood listservs and listservs of community organizations geared toward mothers and families in Wards 5, 7, and 8 of Washington, D.C., which are underserved areas, were used to target recruitment efforts to engage mothers from communities of color and/or underserved backgrounds.

Procedures

Mothers were scheduled for a 30-minute, virtual, study meeting with a research team member in a private Zoom™ room. Mothers provided informed consent via RedCap™ prior to completing a brief survey. The survey included questions about the mother’s and infant’s demographics, infant’s birthweight and current weight, infant feeding practices, whether the mother had received advice from their doctor during the formula shortage; information sources influencing their decisions about infant feeding and what sources of information they trust (Appleton et al., 2020), and whether they perceived various alternatives to infant formula as safe. Following completion of the survey, an in-depth interview was conducted by one of two trained, female, interviewers using a semi-structured guide developed by the research team (Supplement 1). The guide included questions about mothers’ feelings related to the shortage, difficulties finding formula during the shortage, the extent to which mothers perceived the shortage impacted their infants’ diet, weight, and health, and how the shortage affected their experience as the mother of an infant.

Interviews occurred between June 22, 2022, and September 15, 2022, at which point forty-five mothers enrolled and saturation of the data had been reached. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim using NVivo Transcription. Each mother received $50 as compensation via direct deposit, check, or debit card per participant preference. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the George Washington University (IRB #: NCR224282) and reporting of qualitative findings is in accordance with the COREQ guidelines.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participants’ demographics and survey responses. Three coders independently coded an initial subset of three transcripts using Microsoft Word, which formed the basis of a shared codebook. Two coders coded the remaining transcripts using the shared codebook. The coders added new codes as they emerged and reorganized existing codes to develop the final codebook (Supplement 2). All transcripts were reviewed by the three coders to ensure coding complied with the final codebook, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion among the three coders and an additional research team member. After coding was completed on all transcripts, similarities and differences across race/ethnic and income subgroups (i.e., white vs. Black/African American and eligible vs. ineligible for SNAP or WIC) were examined using an exploratory approach by comparing the presence and frequency of codes across subgroups. Thematic analysis was used to identify emergent themes and subthemes, which were discussed amongst the research team, and refined collaboratively. Representative quotations for each theme and subtheme were selected.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The sample was racially diverse (Table 1), with 31% self-reporting as Black or African American, 11% self-reporting as Asian, and 7% self-reporting as more than one race. Of 11 mothers who reported SNAP and/or WIC eligibility, 9 (82%) self-identified as Black or African American. The mean age of the infants was 4.5 months and approximately half reported their infant was female (49% female, 51% male).

Quantitative Results

Most mothers reported using infant formula, whether exclusively (29%) or in combination with breast milk (42%), while 29% reported exclusively breastfeeding their infant. Of those using formula, 36% indicated using specialty formula, and nearly half (44%) reported switching brands and/or types of formula due to the shortage.

While 69% of mothers reported receiving information about infant feeding from their doctor or midwife (for their present infant), only 18% reported receiving feeding advice from their doctor or midwife specifically regarding the formula shortage (Table 2). Most mothers indicated family (58%) and healthcare workers (60%) influenced their opinion about what to feed their infant, and half indicated they trusted friends or family to provide accurate information about infant feeding. While 84% of mothers reported they trusted medical professionals to provide accurate information about infant feeding, along with medical organizations (e.g., American Academy of Pediatrics) and government agencies (e.g., United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), they did not feel supported in obtaining infant formula during the shortage. Additionally, although most mothers correctly indicated that making their own infant formula, substituting toddler milk for infant formula, or diluting infant formula were unsafe, several mothers (9%, 7%, and 9%, respectively) perceived these practices as safe. None of the mothers indicated cow’s milk as a safe alternative for infant formula.

Qualitative Results

Theme 1. The Infant Formula Shortage Adversely Impacted Mothers’ Mental and Emotional Health

A key overarching theme was the infant formula shortage adversely impacted mothers’ mental and emotional health (Table 3). Mothers experienced significant anxiety related to the infant formula shortage, specifically surrounding the prospect of not being able to find formula and fear that other mothers were unable to locate formula. Mothers also reported anxiety about their infant gaining weight appropriately if they were unable to locate formula. They described feelings of sadness, shock, and disbelief that a formula shortage could happen in the U.S. Even mothers who were exclusively breastfeeding reported considerable anxiety about needing to rely on breastfeeding and not having formula as a back-up, given the possibility that formula may not be available. Mothers described feelings of general stress about the shortage, as well as anger about the situation. Guilt about feeding their infant formula and heightened pressure to breastfeed and maintain their milk supply were also described.

Theme 2. The Infant Formula Shortage had Significant Financial and Intangible Costs

Another key overarching theme was that navigating the infant formula shortage had significant financial and intangible costs (Table 4). Mothers described financial strain resulting from the shortage; and in some cases, obtaining formula came at the expense of other basic household necessities, such as food or rent. Mothers who were enrolled in WIC described difficulties using their WIC benefits for formula during the shortage. Even mothers who indicated no difficulties affording formula described spending more on formula than planned due to rising costs of formula and the need to purchase formula in larger quantities or “stockpile.” Mothers also described intangible costs, including spending exorbitant amounts of time and energy searching for formula; this entailed driving from store to store, sometimes for hours, and searching online. Mothers also described feeling exhausted from the shortage, sacrificing their physical and emotional health, and changing their diet and lifestyle to prolong breastfeeding and/or continue pumping to avoid reliance on formula.

Theme 3. The Infant Formula Shortage Led to Changes in Infants’ Diet

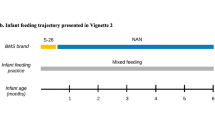

A third overarching theme was that the shortage led to changes in infants’ diets (Table 5). Mothers explained that their infant received fewer calories due to not having enough formula, resulting in they perceived to be inadequate weight gain. Mothers who were able to breastfeed mentioned freezing extra milk to have a back-up, and in some cases, donating extra breast milk to help others. Mothers also reported making efforts to conserve formula by reducing how much they provided to their infant, minimizing wasted formula, saving leftover formula, encouraging their infant to finish bottles, and earlier introduction of solid foods. Two mothers reported providing their infant with toddler milk or juice because infant formula was unavailable.

Theme 4. Social Networks Were Helpful in Navigating the Infant Formula Shortage but Mothers did not Feel Supported by the Government

Another theme was mothers found social networks helpful in locating infant formula but did not feel supported by the government and were frustrated by a general lack of support for breastfeeding (Table 6). Mothers explained they were able to locate formula through social media groups and friends and family in other parts of the country. A new or amplified sense of community was also described, where mothers were unified due to the difficulty of the situation.

Theme 5. Mothers Felt Lucky to have the Ability to Breastfeed and/or Obtain Formula During the Shortage

A final emergent theme was mothers felt lucky to be able to breastfeed and have resources to obtain formula (Table 7). Breastfeeding mothers explained feeling fortunate that their infant was able to latch and/or that their milk supply was plentiful. Mothers reported feeling grateful that they had supportive family members and friends who helped them find formula. Mothers also described feeling grateful that they had resources to obtain formula, financial means to purchase more expensive formula or enroll in formula subscription services, and lived near a plethora of retail outlets selling formula. This sentiment was primarily described by white mothers. While white and Asian mothers often described using subscription, delivery, and text services to obtain formula during the shortage, such services were not mentioned by any Black or SNAP- or WIC-eligible participants.

Subthemes Across Sociodemographic Subgroups

Several other subthemes also differed across sociodemographic subgroups. While feeling heightened pressure to breastfeed and guilt about not breastfeeding were widely described by white and Asian mothers and those not eligible for SNAP or WIC, this was not frequently described by Black mothers or by mothers eligible for SNAP or WIC. Meanwhile, Black mothers and those eligible for SNAP or WIC tended to describe a hesitancy to switch formulas and indicated their infant required a specific formula due to a pre-existing condition. While receiving help finding formula from friends and family and social media networks were described across race and income subgroups, these resources were described more frequently by white mothers and those not receiving SNAP or WIC benefits.

Discussion

The infant formula shortage adversely impacted mothers’ mental and emotional health; and, navigating the situation had significant and unanticipated financial, physical, emotional, and lifestyle-related (e.g., time) costs. Although in some cases mothers reported their infant received fewer calories due to the shortage and/or had gastrointestinal problems resulting from switching formula, most described altering their planned and/or preferred feeding practices to ensure their infant received adequate nutrition and did not suffer serious health consequences.

Unfavorable mental, emotional, physical, financial, and lifestyle-related impacts of the shortage were widely described irrespective of mothers’ sociodemographic characteristics; however, the most severe financial impacts were described by mothers who were eligible for SNAP and/or WIC. While WIC is a supplemental program and is not designed to meet all formula needs for infants enrolled in the program, mothers described challenges using their WIC benefits during the shortage and had to pay for formula out-of-pocket, resulting in significant financial strain. It is important to note that while the present study was conducted among mothers in Washington, D.C., resources and support available to families enrolled in WIC during the infant formula shortage varied across states, and complications using WIC during the shortage were observed throughout the U.S. (Kalaitzandonakes et al., 2023).

Mothers in our study expressed frustration at the general lack of support for breastfeeding and the physical, emotional, and time-related barriers to continue breastfeeding, consistent with prior literature (Li et al., 2008). In order to better support the unique needs of breastfeeding mothers, community-based organizations could be leveraged to connect mothers to resources, such as culturally relevant breastfeeding advertisements, resource guides, and virtual breastfeeding workshops (Lilleston et al., 2015). While feeling grateful to be able to breastfeed was described across race and income subgroups, Black mothers and mothers from low-income households described facing heightened challenges to breastfeeding during the shortage, including inflexible work schedules, shorter paid maternity leaves, and/or not working in an environment conducive to pumping. The U.S. remains the only industrialized country without a national paid maternity leave policy despite notable mental and physical health benefits for mothers and infants. And racial inequities in the conduciveness of the work environment for breastfeeding (Van Niel et al., 2020) are well-described barriers to breastfeeding in the infant feeding literature (Jones et al., 2015).

Adverse consequences of the formula shortage on mothers’ mental and emotional health are particularly alarming because the postpartum period is already a time of heightened stress (Tully et al., 2017). In the year following the birth of a child, 15% of women suffer from postpartum anxiety (Shorey et al., 2018), and approximately 12.5% of women in the U.S. have postpartum depression (United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Both conditions have unfavorable short and long-term impacts on maternal and infant health (Grace et al., 2003) and also interfere with mother-child bonding (Dubber et al., 2015) and infant feeding outcomes (Fallon et al., 2016). Even in the absence of postpartum anxiety and/or depression, the months following childbirth involve sleep exhaustion, feelings of isolation, new demands of parenting, and changes in physique and sexuality, all of which detract from mothers’ mental and physical health (Walker & Murry, 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated mental health challenges during the postpartum period and posed a barrier to accessing postpartum medical care and social support (Goldstein et al., 2022).

Difficulty finding formula and the prospect of hypothetically being unable to feed their infant were key contributors to reported stress and anxiety associated with the formula shortage. Even in the absence of an infant formula shortage and global pandemic, feelings of maternal shame and anxiety surrounding infant feeding practices (Thomson et al., 2015) and a lack of social and institutional support for breastfeeding in the U.S. (United States Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, 2023a) are well-documented. Experiencing breastfeeding problems leads to feelings of disappointment, guilt, failure, shame, and frustration (Ikonen et al., 2015), as breastfeeding is tied to mothers’ self-worth and identity (Demirci et al., 2018). Mothers in our study who reported exclusively breastfeeding described considerable anxiety about their milk supply and ability to avoid switching to formula due to the shortage. Stress associated with the perception of inadequate milk supply is widespread, and often leads to cessation of breastfeeding (Li et al., 2008) and/or supplementation with infant formula (Bookhart et al., 2021).

Mothers whose infants were fed formula described spending exorbitant amounts of time searching for formula, which further aggravated their stress and anxiety associated with the shortage. Time spent searching for formula was reported to contribute to exhaustion, disrupt work productivity and detract from time spent with older children. Considering that time constraints are a key barrier to healthy eating and physical activity among postpartum women (Ryan et al., 2022), which are important for preventing postpartum weight retention (Amorim Adegboye & Linne, 2013) and psychological morbidity (Dipietro et al., 2019), excessive time spent searching for formula may also have indirect, unfavorable impacts on mothers’ physical and psychological health.

Avoidance of infant health problems due to the formula shortage was predominantly attributed to mothers’ ability to breastfeed and/or ultimately finding sufficient formula after taking extreme or unconventional measures to acquire formula (e.g., leveraging social and family networks, searching multiple stores). While reported changes such as conserving formula through saving leftover formula for subsequent feeds and encouraging their infant to finish bottles did not result in major health problems, these practices are inconsistent with bottle-feeding guidance (United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021) and may pose risks to infant food safety (United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021) and contribute to overfeeding (Li et al., 2012). Furthermore, mothers reported providing their infant with solid foods earlier than planned, which is concerning because early introduction of solids is associated with later childhood obesity, particularly among formula-fed infants (Daniels et al., 2015). Two mothers reported providing their infant with bottles of toddler milk or fruit juice as a substitute when formula was unavailable during the shortage, both of which are not recommended by public health and medical organizations (Healthy Eating Research, 2019). Milk banks provide a safer alternative to high risk infant feeding practices; yet they remain underutilized, especially during public health emergencies, due to inaccessibility of donor milk, infant feeding needs (i.e., specialty formula), and mothers’ perceptions and preferences (Kalaitzandonakes et al., 2023).

Alarmingly, some mothers (7–9%) did not recognize that infant feeding practices such as making their own infant formula, substituting toddler milk for infant formula, or diluting formula to make it last longer were unsafe, which underscores the need for medical professionals and government agencies to provide mothers with more education about infant feeding. In fact, 5.6% of parents in the U.S. attempted to make formula at home and 13.3% substituted with a product other than formula or breast milk, such as cow’s milk (Kalaitzandonakes et al., 2023). Encouragingly, no mothers in the present study identified cow’s milk as a safe alternative to formula. As only 18% of mothers reported receiving information from their doctor or midwife about feeding their present infant (i.e., their most recent pregnancy and delivery as opposed to for any prior children) during the shortage, more proactive outreach by healthcare providers during emergencies is needed. Nearly half of the mothers in our sample reported that they trusted friends and family to provide accurate information about infant feeding, both of which are common sources of health misinformation (Suarez-Lledo & Alvarez-Galvez, 2021). Fortunately, healthcare providers and medical organizations were reported as the most trusted sources of information.

Social, partner, and family support were critical facilitators of acquiring infant formula during the shortage and are known to positively influence mothers’ physical and mental health during the postpartum period (Faleschini et al., 2019). Mothers described social media groups as a key source of support in navigating and locating formula during the shortage. Social media is an important source of social support during pregnancy and postpartum (Baker & Yang, 2018), and further efforts to provide postpartum women with support and reputable resources through online and in-person social networks are warranted.

Limitations

Key limitations of this study include the focus specifically on mothers in Washington, D.C and the virtual data collection methods, which may limit the extent to which the findings are generalizable to mothers in other regions of the country or those that do not have access to internet and social media. Furthermore, only about one-quarter of the sample was eligible for WIC or SNAP, which is lower than national rates (United States Department of Agriculture, 2022) and 82% had educational attainment of college or higher, compared to approximately 38% nationwide (United States Census Bureau, 2022). While one of the two interviewers on the research team identifies as a woman of color, greater diversity among team members may have increased participation from marginalized communities. However, the consistency of the present findings with recent quantitative studies examining impacts of the infant formula shortage across the nation enhances the likelihood that our findings are broadly applicable. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine mothers’ experiences during the 2022 infant formula shortage and is further strengthened by the racially diverse sample of participants.

Conclusion

Findings call attention to concerning impacts of the infant formula shortage on mothers’ mental and emotional health and highlight the importance of social and family support in locating and acquiring infant formula during the shortage, which can be utilized in future emergency outreach efforts. These results demonstrate disproportionate adverse impacts of the shortage on Black mothers and mothers from low-income households and emphasize the urgent need to implement proper advocacy channels within the community to address systemic inequities in infant feeding practices. Enhanced efforts to connect mothers with community health workers and health advisors are needed to educate mothers about providing their infants with proper nutrition, particularly during shortages or other unexpected crises that may pose a barrier to infant feeding. Sustainable policy solutions to support infant feeding (i.e., national guaranteed paid maternity leave and increased access to milk banks), address this unprecedented crisis, and prevent recurrences, should be pressing public health priorities.

Data Availability

Data described in the manuscript will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Code Availability

The code book used to code the data manuscript will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Abrams, S. A., & Duggan, C. P. (2022). Infant and child formula shortages: Now is the time to prevent recurrences. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 116(2), 289–292. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqac149.

Amorim Adegboye, A. R., & Linne, Y. M. (2013). Diet or exercise, or both, for weight reduction in women after Childbirth. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, (7), CD005627. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005627.pub3.

Appleton, J., Fowler, C., Laws, R., Russell, C. G., Campbell, K. J., & Denney-Wilson, E. (2020). Professional and non-professional sources of formula feeding advice for parents in the first six months. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 16(3), e12942. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12942.

Attainment Data Census.Gov. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/educational-attainment.html.

Baker, B., & Yang, I. (2018). Social media as social support in pregnancy and the postpartum. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare : Official Journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives, 17, 31–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2018.05.003.

Bookhart, L. H., Joyner, A. B., Lee, K., Worrell, N., Jamieson, D. J., & Young, M. F. (2021). Moving Beyond Breastfeeding initiation: A qualitative study unpacking factors that influence infant feeding at Hospital Discharge among Urban, socioeconomically disadvantaged women. J Acad Nutr Diet, 121(9), 1704–1720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2021.02.005.

Calder, R. S. D., Grady, C., Jeuland, M., Kirchhoff, C. J., Hale, R. L., & Muenich, R. L. (2021). COVID-19 reveals vulnerabilities of the food-energy-water Nexus to viral pandemics. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 8(8), 606–615. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00291.

Choi, Y. Y., Ludwig, A., Andreyeva, T., & Harris, J. L. (2020). Effects of United States WIC infant formula contracts on brand sales of infant formula and toddler milks. Journal of Public Health Policy, 41(3), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-020-00228-z.

consumed an estimated 56% of U.S. infant formula in 2018. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=103970.

Daniels, L., Mallan, K. M., Fildes, A., & Wilson, J. (2015). The timing of solid introduction in an ‘obesogenic’ environment: A narrative review of the evidence and methodological issues. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39(4), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12376.

Demirci, J., Caplan, E., Murray, N., & Cohen, S. (2018). I just want to do everything Right: Primiparous women’s accounts of early breastfeeding via an app-based Diary. Journal of Pediatric Health Care : Official Publication of National Association of Pediatric Nurse Associates & Practitioners, 32(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.09.010.

Dipietro, L., Evenson, K. R., Bloodgood, B., Sprow, K., Troiano, R. P., Piercy, K. L., Vaux-Bjerke, A., & Powell, K. E. (2019). & Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory, C. Benefits of Physical Activity during Pregnancy and Postpartum: An Umbrella Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 51(6), 1292–1302. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001941.

Dubber, S., Reck, C., Muller, M., & Gawlik, S. (2015). Postpartum bonding: The role of perinatal depression, anxiety and maternal-fetal bonding during pregnancy. Archives Women’s Mental Health, 18(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0445-4.

Faleschini, S., Millar, L., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Skouteris, H., Hivert, M. F., & Oken, E. (2019). Women’s perceived social support: Associations with postpartum weight retention, health behaviors and depressive symptoms. Bmc Women’s Health, 19(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0839-6.

Fallon, V., Groves, R., Halford, J. C., Bennett, K. M., & Harrold, J. A. (2016). Postpartum anxiety and infant-feeding outcomes. Journal of Human Lactation : Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 32(4), 740–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334416662241.

General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/resources/calltoaction.htm.

Goldstein, E., Brown, R. L., Lennon, R. P., & Zgierska, A. E. (2022). Latent class analysis of health, social, and behavioral profiles associated with psychological distress among pregnant and postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Birth. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12664.

Grace, S. L., Evindar, A., & Stewart, D. E. (2003). The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: A review and critical analysis of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health, 6(4), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-003-0024-6.

Healthy Eating Research (2019). Healthy Beverage Consumption in Early Childhood: Recommendations from Key National Health and Nutrition Organizations. https://healthyeatingresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/HER-HealthyBeverage-ConsensusStatement.pdf.

Ikonen, R., Paavilainen, E., & Kaunonen, M. (2015). Preterm infants’ mothers’ experiences with milk expression and breastfeeding: An integrative review. Advances in Neonatal Care : Official Journal of the National Association of Neonatal Nurses, 15(6), 394–406. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000232.

Jones, K. M., Power, M. L., Queenan, J. T., & Schulkin, J. (2015). Racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding. Breastfeeding Medicine : The Official Journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(4), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2014.0152.

Kalaitzandonakes, M., Ellison, B., & Coppess, J. (2023). Coping with the 2022 infant formula shortage. Preventive Medicine Reports, 32, 102123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102123.

Li, R., Fein, S. B., Chen, J., & Grummer-Strawn, L. M. (2008). Why mothers stop breastfeeding: Mothers’ self-reported reasons for stopping during the first year. Pediatrics, 122(Suppl 2), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1315i.

Li, R., Magadia, J., Fein, S. B., & Grummer-Strawn, L. M. (2012). Risk of bottle-feeding for rapid weight gain during the first year of life. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 166(5), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1665.

Lilleston, P., Nhim, K., & Rutledge, G. (2015). An Evaluation of the CDC’s community-based Breastfeeding Supplemental Cooperative Agreement: Reach, Strategies, barriers, facilitators, and lessons learned. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 31(4), 614–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415597904.

Paris, M. (2022, June 2). One in Five US States Is 90% Out of Baby Formula. Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-02/us-baby-formula-shortages-hit-74-despite-biden-action.

Report Card. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm.

Ryan, R. A., Lappen, H., & Bihuniak, J. D. (2022). Barriers and facilitators to healthy eating and physical activity Postpartum: A qualitative systematic review. J Acad Nutr Diet, 122(3), 602–613e602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2021.11.015.

Shorey, S., Chee, C. Y. I., Ng, E. D., Chan, Y. H., Tam, W. W. S., & Chong, Y. S. (2018). Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 104, 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.08.001.

Standish, K. R., & Parker, M. G. (2022). Social determinants of Breastfeeding in the United States. Clinical Therapeutics, 44(2), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.11.010.

Suarez-Lledo, V., & Alvarez-Galvez, J. (2021). Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(1), e17187. https://doi.org/10.2196/17187.

Thomson, G., Ebisch-Burton, K., & Flacking, R. (2015). Shame if you do–shame if you don’t: Women’s experiences of infant feeding. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12148.

Tully, K. P., Stuebe, A. M., & Verbiest, S. B. (2017). The fourth trimester: A critical transition period with unmet maternal health needs. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(1), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.03.032.

United States Census Bureau (2022). February 24). Census Bureau Releases New Educational.

United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021, July 12). Feeding from a bottle. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/infantandtoddlernutrition/bottle-feeding/index.html.

United States Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (2023a, April 4). The Surgeon.

United States Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (2023b, April 13). 2022 Breastfeeding.

United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Depression among women. Retreived July 20, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/depression/

United States Department of Agriculture (2022, May 23). Infants in USDA’s WIC Program.

United States Food and Drug Administration (2023). FDA Investigation of Cronobacter Infections: Powdered Infant Formula (February 2022). FDA. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/powdered-infant-formula-recall-what-know.

Van Niel, M. S., Bhatia, R., Riano, N. S., de Faria, L., Catapano-Friedman, L., Ravven, S., Weissman, B., Nzodom, C., Alexander, A., Budde, K., & Mangurian, C. (2020). The impact of Paid Maternity leave on the Mental and Physical Health of Mothers and children: A review of the literature and policy implications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 28(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000246.

Walker, L. O., & Murry, N. (2022). Maternal stressors and coping strategies during the extended Postpartum Period: A retrospective analysis with contemporary implications. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle), 3(1), 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1089/whr.2021.0134.

What You Need To Know About the Baby Formula Shortage (2022). May 17). Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2022-us-baby-formula-shortage-explained/.

Funding

This project was funded by an internal Research Enhancement Award (PI: Sylvetsky) from the Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ACS, JM, JS, and ERS conceptualized and designed the study. ACS and JTK collected data. ACS, SAH, JTK, and HRM analyzed data. ACS drafted the initial manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approve of the final version submitted to MCHJ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

ACS is engaged in consulting work on behalf of Abbott. None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the George Washington University (IRB #: NCR224282).

Consent to Participate

Mothers provided informed consent via RedCap™ prior to participation.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sylvetsky, A.C., Hughes, S.A., Kuttamperoor, J.T. et al. Mothers’ Experiences During the 2022 Infant Formula Shortage in Washington D.C.. Matern Child Health J 28, 873–886 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03860-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03860-9