Abstract

Objectives

The US opioid epidemic contributes to a growing population of children experiencing neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). A review of the developmental impacts of the opioid crisis highlights that both prenatal exposure to teratogens and ACEs can result in developmental delay and disabilities. Training for the early intervention/early childhood (EI) systems is needed to enable them to meet the needs of this growing population.

Methods

To address this, an IRB-approved online training on best practices for NAS, developmental monitoring and referral, and trauma-informed care was created for Ohio EI providers who provided informed consent to participate. The feasibility of utilizing an online training was assessed. Knowledge on opioid addiction, NAS, ACEs, and early intervention provider characteristics were collected for 2973 participants.

Results

Within 6 months, the training reached providers in all Ohio counties and seventeen other states. 57% of providers reported caring for one or more children with a caregiver who has confirmed opioid use. 31% reported these children had experienced four or more ACEs. Providers’ ACEs awareness was moderately associated with their experiences with prenatally-exposed youth. There was a significant increase in knowledge following training. Differences in post-training knowledge differed only by county-level opioid death rates, where those providers with low-medium opioid death rates reported more awareness of children with prenatal opioid exposure compared to participants who lived in a county with medium and medium-high opioid death rates.

Conclusions

Online-training is feasible for closing gaps in the early intervention system.

Significance

What is already known on this subject? The opioid epidemic in the United States has claimed millions of lives in the past two decades. The epidemic is associated with neonatal abstinence syndrome and traumatic event exposure to young children, which has detrimental effects on children’s development. Young children affected by the opioid epidemic are being referred at high rates to early intervention services.

What this study adds? We consolidated the evidence-based research on the topics and provided them in an asynchronous web-based training to the early childhood workforce. We then examined the feasibility and significance of the training on early childhood workforce knowledge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Significance

The United States is in an opioid epidemic (Dasgupta et al., 2014), with transgenerational impacts of maternal opioid use (Byrnes et al., 2011, 2013; Johnson et al., 2011). Opioid misuse by pregnant women has led to increases in overdoses, and a rise of children with in utero exposure needing early intervention (EI) services. Research suggests broad and complex implications, including developmental delays due to prenatal exposure, abuse, and neglect (Finnegan et al., 1975; Freeman et al., 2002; Medrano et al., 2002; Patrick et al., 2012; Saia et al., 2016; Suchman et al., 2006). Parent substance use can have detrimental effects on children’s mental health (Peisch, 2018; Rosen & Johnson, 1985; Van Baar, 1990). The stigma associated with parental substance use, adverse childhood experiences, and in utero exposure to substances may also contribute to developmental delays. We provide evidence for an asynchronous training for the early childhood workforce (ECW) on the impact of the opioid crisis on infants and young children and tools to meet their needs.

Training the Early Childhood Workforce (ECW)

The lack of information accessible to the ECW on the impact of the opioid epidemic on young children has been a critical barrier to developmental and mental health progress. In 2018, 54% of all 3–5 year-olds nationally attended preschool (CPS, 2018). 13% of young children receive home-based care from relatives, while 19% have no routine early care and education services (NCES, 2019). In 2016, 5.2% of US children birth to 2-years-old were served under Part C; this figure rose 1.2% from 2007 (NCES, 2019). After controlling for maternal tobacco use, education level, child’s birth weight, gestational age, and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit admission, children with a history of NAS (n = 1815) were more likely to be referred for a disability evaluation compared to children without NAS (n = 5441; 15.6 vs 11.7%, p < .0001), and to require classroom interventions (15.3 vs 11.4%, p < .0001; Fill et al., 2018). Because of the high volume of children being referred for disability services, ECW may benefit from learning evidence-based research on the developmental and mental health difficulties that these youth face.

Prior to Coronavirus, ECW trainings were in person, which presented barriers particularly for rural providers. The current system requires that providers who accept Medicaid waivers and licensed childcare centers participate in continuing education (CE). Child Care Resource & Referral Association (CCRRA) is the accrediting body of CE courses for the ECW in the state. Trainings are listed on the CCRRA website for participants to sign up. Our team developed a web-based training for ECW, which was informed by a review of the literature. The training modules included information on opioids and substance use, emerging best practices for NAS, developmental monitoring and referral, and trauma-informed care.

Young children are disproportionately exposed to the opioid epidemic and childhood traumatic events (CTE; PCSAO, 2017). Separation from caregivers because of parental substance use and childhood traumatic events has been associated with increased risk for mental health difficulties and developmental delays (Kaltenbach & Jones, 2016; Larson et al., 2019). The opioid epidemic is complex in regard to understanding risks and associated sequalae. Current public policies that utilize a punitive approach as opposed to a trauma-informed care approach to substance use disorders appear to contribute to the complexities of the opioid epidemic on young children (Kaltenbach & Jones, 2016). Around 75–90% of infants exposed in utero to opioids and other substances experience neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS; Hudak & Tan 2012), which is an acute withdrawal syndrome from substances. Some infants exposed to opioids in utero experience no NAS symptoms. There is a distinction in the literature between NAS and neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), which can be difficult to delineate due to the lower likelihood of single substance use (e.g., opioids only versus opioids and nicotine or other substances). Thus, we focus on NAS, which incorporates NOWS, as opposed to NOWS exclusively. NAS symptoms vary by infant and can impact the central nervous, autonomic, and gastrointestinal systems (Hudak & Tan, 2012). NAS is a risk factor for abuse and neglect (Lynch et al., 2018; Uebel et al., 2015), which has developmental and psychological adversities (Hildyard & Wolfe, 2002).

Understanding the risks of in utero exposure to opioids is also complicated by whether a woman who is pregnant received treatment for her substance use disorder, the extent of her compliance with treatment and prenatal care for her fetus (Finnegan, 1978; Strauss et al., 1974). For example, infants born to women who received treatment for their opioid use disorder while pregnant experienced higher birth weight and were less likely to be premature compared to women who did not receive treatment for opioid use disorder while pregnant (Kotelchuck et al., 2017). Risks of in utero exposure to opioids is further complicated by whether pregnant women have also experienced traumatic events at any time before and during her pregnancy (Chaplin & Sinha, 2013; Schwerdtfeger & Goff, 2007). There is less research on fathers’ histories of traumatic event exposure on the intergenerational transmission of stress; however, the research available suggests fathers can transmit stress response via sperm and appear to play a role in shaping the stress response of their children (Bowers & Yehuda, 2016). For example, there are genetic, social, and environmental factors that contribute to the complex interplay of the intergenerational transmission of traumatic stress (Clayton et al., 2009; Compton et al., 2005; Thomas, 2007) by both mothers and fathers (Bowers & Yehuda, 2016). We underscore that vulnerability for developmental delays and mental health difficulties underlies young children’s risks who are impacted in some way by the opioid epidemic. Individuals with childhood traumatic events (CTE) access health care up to 2.5 times more than those with no CTE (Koss & Heslet, 1992), thus the economic healthcare costs are $333-$750 billion dollars annually (Dolezal et al., 2009). The intergenerational transmission of CTE facilitates and maintains opioid use disorders and traumatic stress. Although the research on opioid exposure in utero has inconclusive findings on long-term developmental effects, research does support in utero exposure and environmental impacts (e.g., socioeconomic factors, traumatic stress, stigma of having a parent with a substance use disorder) in combination make children vulnerable to negative developmental outcomes (Welton et al., 2019).

In the current study, a web-based training was developed for ECW and focused on providing education about NAS, traumatic stress, developmental delays monitoring and referral, and addiction basics. We hypothesized that the web-based training would be disseminated statewide within a year. We also hypothesized that the training would increase participants’ knowledge. Finally, we hypothesized that participants who had worked with youth with either in utero exposure or Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) would learn less from the training than participants who were unaware of youth in their care with opioid exposure or ACEs.

Method

Recruitment

ECW were recruited through the state CCRRA website. Potential participants were able to view a training description among a list of other CCRRA-accredited trainings and decide whether to access it for CE credits. Information about the training was also included on the University website. An IRB-approved announcement of the training was circulated to state and national organizations and agencies (e.g., Early Intervention Programs, Head Start, Division of Early Childhood, and University Centers on Disabilities) with the request to circulate to their membership. Finally, participants could forward the link to others.

Procedures

This study was approved by the IRB and conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were provided access to the training via a web link. Upon clicking the link, they saw a slide containing the consent to participate in this IRB-approved study. They had the opportunity to decide if they would like to participate. All interested individuals were granted access to the web-based training regardless of whether they decided to participate in the pre-posttest. Only those who signed up on the CCRRA website and participated in the research project were granted CE credit. The training was provided at no cost to the participants. No other incentives were provided. On average, the training took 1 hour to complete. This training included video interviews with nurse navigators, a foster parent, and an OBGYN specialized in working with pregnant women who have opioid use disorders. We included a case narrative woven throughout the modules to apply knowledge learned to a simulated case. Further, the training included written text about the topics. Please refer to Edrees et al., (2022) for a full review of the development of the web-based training. Overall, Edrees et al., (2022) found the training to be well-received by participants.

Measures

A Demographic Questionnaire given during the pre-test asked about state, county, zip code, age, sex, race, ethnicity, highest level of education, professional license(s), current occupation and setting, Head Start program affiliation (yes/no), and length of time working in childcare and current position.

Awareness of Opioid Exposure Questionnaire, given during the pre-test, was a five-item survey about awareness of youths’ in utero exposure, and/or having a parent/caregiver suspected of or confirmed use of opioids. The response options were “Yes/No/I don’t know”. The items were developed by our team for the purpose of measuring participants’ awareness of parental opioid use and in utero exposure. This questionnaire was added after data collection had started, so we do not have this information on 46% of participants (n = 1367). The internal consistency was excellent, α = 0.80.

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Survey (ACEs; Felitti, 1998), given during the post-test, is a 10-item survey asking about childhood negative life events (e.g., parents divorced, had a parent who was incarcerated, verbally abusive or domestic violent household) and was modified. Instead of asking about the adult’s childhood experiences, the questions were rephrased to ask, “That you are aware of, have any of the children that you are currently working with experienced any of the following?” The internal consistency was excellent, α = 0.87.

Knowledge Survey consisted of 16-items assessing knowledge of addiction, NAS, traumatic stress in young children, and developmental monitoring and referral for services was given at the pre- and post-test. The response format was 4- or 5-item multiple choices. Pre-/Posttest internal consistency was low, α = 0.42 and 0.43.

Training Feedback We had a question on the post-test asking for open-ended responses to the training.

Participants

Participants were 2973 adults (92% female, 3% male, < 1% other, 5% declined to answer) aged 18 + who are early intervention specialists, childcare providers, or others who work with 0–5-year-olds. Most were between 25 and 44 years old (53%), Caucasian (69%), and had completed some college or obtained a post-secondary degree (66%; refer to Table 1). Participants were mostly from Ohio (91%). All 88 Ohio counties were represented. The 9% who were not from Ohio identified as being from Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, West Virginia, Wyoming, and Washington. 63% self-reported having had no experience with children with in utero opioid exposure, 2% were not sure, and 36% had prior experience. The Ohio Department of Health has previously categorized counties by opioid overdose death rates (Ohio Department of Health, 2020). Utilizing these categories, we highlight the reach of our training to counties with the highest levels of opioid overdose deaths (See Fig. 1).

Ohio participant representation by opioid overdose death rate. Figure of the percentage of participants from Ohio by the opioid overdose death rate in the county. Illustrates that most participants were coming from areas where there was a high need for information on the impact of opioid in utero exposure on young children

Results

Post-test data was available for 1907 participants (retention rate = 64%). Those who completed and those who did not complete the post-test differed in their work position, X2 (7, N = 2971) = 28.93, p = .000. In-Home Health Providers, Teacher Aides, and Center Directors were more likely to complete the post-test. Participants who had fewer years working in childcare (M = 11.08, SD = 9.19) were less likely to complete the post-test compared to those with more years (M = 11.95, SD = 9.62), t(2953) = -2.38, p = .02. Those who work in Head Start were less likely to complete the post-test compared to those who do not, X2 (1, N = 2971) = 12.98, p = .000. We found no other demographic differences: age, X2 (5, N = 2917) = 4.81, p = .441; sex, X2 (1, N = 2796) = 0.730, p = .393; race/ethnicity, X2 (4, N = 2782) = 8.77, p = .067; education, X2 (4, N = 2773) = 6.10, p = .192; licensed, X2 (1, N = 2698) = 0.018, p = .894; work setting, X2 (2, N = 2971) = 1.00, p = .606; county, X2 (5, N = 2923) = 4.76, p = .446; years in current role, t(2960) = − 0.479, p = .63.

Awareness of Opioid Exposure

About half (57%) had one or more children with a parent/caregiver who had confirmed opioid use. 62% had one or more children that they suspected has a parent/caregiver who uses opioids. Participants who lived in a county with low-medium opioid death rates reported more awareness of children with prenatal opioid exposure compared to participants who lived in a county with medium and medium-high opioid death rates, X2 (5, N = 1588) = 47.19, p < .001.

Awareness of ACEs

Participants reported being aware of an average of 2.8 ACEs experienced by children in their care. 31% reported that the children they worked with experienced four or more ACEs. After excluding the 9% of participants from outside of Ohio, there was not a significant difference, X2 (5, N = 817) = 42.81, p = .755), in awareness of ACEs by Ohio county opioid death rate.

We investigated the relationship between ACEs awareness (broken down by any ACEs and total number of ACEs awareness) and opioid exposure awareness. Participants’ awareness of ACEs was moderately associated (r = .47) with their experience with youth exposed in utero to opioids (See Table 2). We also found a strong correlation between knowledge of youth’s confirmed in utero exposure and awareness of parental opioid use (r = .71).

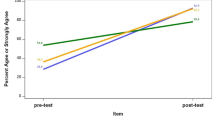

Evaluating Participants’ Learning

We found a significant difference in the participants’ knowledge growth after completion of the online learning modules, measured by pre- (M = 10.17, SD = 1.94) and post-test (M = 11.26, SD = 1.92), t(1906) = 24.586, p = .000. To evaluate whether awareness of ACEs or in-utero opioid exposure impacted knowledge growth, participants were divided into low or no awareness versus moderate to high awareness using a median split. Baseline level of education, awareness of ACEs, t(357) = 1.39, p = .166, nor awareness of opioids in-utero, t(1024) = 0.487, p = .626, affected learning. We found no difference for either of these measures on pre-/post-test knowledge.

Responses to the question soliciting feedback about the training revealed supplemental qualitative information about the training’s impact on learners’ work. Several themes emerged from the participants’ responses as highlighted next. “The training was wonderful. I can’t wait to apply the techniques and skills that I learned.” “The training was very helpful; I have more ideas for improvement.” “It hit every aspect of the crisis and was informative for childcare providers.” “It was very well executed.” “It was great! I truly enjoyed every part.” “I really liked the Youtube clips. It was a very informative training module on the growing Opioid epidemic and ways to help children exposed as they learn in our early childhood classrooms.”

Discussion

Much of the opioid crisis funding and research has addressed addiction and treatment. With increased opioid use in adults comes exposure to children, both in-utero and during early childhood. While limited, available research demonstrates the impact of this exposure on young children’s development. The burden of the opioid epidemic on our ECW, from neonatal specialty care to early intervention, foster care, childcare centers, Head Start, and preschools, all require broadening the scope of efforts to address factors that can lead to and maintain disabilities across the lifespan. The goal of this project was to provide professional development to the ECW to enable them to meet the needs of these youth. The asynchronous web-based training resulted in significant changes in pre/post knowledge with a wide reach. Additionally, the surveys collected as a part of the training, allowed us to gather information on the characteristics of the children served. This training can serve as a model as we begin to broaden professional development.

Training Impact

Within 4 months, over 1,000 providers had completed this training. The reach of this project, with participants from all 88 counties in Ohio and multiple states, speaks to the ECW demand for professional development on this topic. In addition to reaching all areas of the state, we were able to reach a range of educational levels and professional backgrounds. The reach of the training is likely due to a few factors. Most importantly, our topic is timely, especially in the state of Ohio, where rates of overdose and NAS have continued to rise. Additionally, the training format also likely increased participation, particularly in rural areas of the state where there is a paucity of trainings and logistical and financial challenges to traveling to urban areas for in-person training. This training resulted in small changes in pre/post knowledge and no differences in scores based on education level or other demographic factors. Specifically, we found a one-point difference in pre-post knowledge, which may not reflect a real-world meaningful impact. In reviewing the qualitative responses to the training, it appeared to increase learners’ skillsets, met their needs and piqued their interests.

Characteristics of Children Served

This training allowed us to gather information about the children served by ECWs. Indeed, more than half to two-thirds of ECWs had one or more children in their care with a parent/caregiver with opioid use. Awareness of prenatal exposure varied by county. Participants who lived in a county with low-medium opioid death rates reported more awareness of children with prenatal opioid exposure compared to participants who lived in a county with medium and medium-high opioid death rates. We found the finding surprising with several potential explanations. First, in counties with the most opioid-related deaths the attention and allocation of resources may be funneled toward individuals who have overdosed, leading to the impact on children being under-addressed. We surmised that there could also be a high level of stigma in these communities of being a child whose parent died from an overdose; it might not be talked about outside the family, which impacts provider awareness. Indeed, obituaries do not include drug overdose as reason for death due to the associated stigma. Unfortunately, often the public has the misperception that if ACEs happen when the child is young and people do not talk about it, the child will fare better. We worked to correct this inaccurate misperception, as young children exposed to CTE experience mental health and developmental difficulties.

Participants reported that the children in their care have experienced 2.8 ACEs. 31% of participants reported that the children they worked with experienced four or more ACEs. When compared to national retrospective recall results that indicate 45% experienced one ACE in childhood (Felitti, 1998) this finding is startling. Only one in ten experience three or more ACEs before the age of 17 (Felitti, 1998). In comparison, in Ohio, one in seven adults reported experiencing 3 or more ACEs before age 17 (Groundwork Ohio, 2018). Given that we are specifically talking about 0–5 year-olds, this finding is an alarming number of ACEs.

We have some limitations that should be considered. First, all reports of the children’s experience of ACEs, including opioid/substance use by parents were reported by the ECWs. One concern is the possibility of both under- and over-reporting. Secondly, we relied on ECWs’ report to indicate the number of children with previous prenatal exposure that they served. Possibly due to stigma concerns and prohibitions on sharing health information, this information may be underreported to ECWs. Further, we were unable to track how many individuals began the training but did not complete it, and those who completed the training, but did not complete post-test. Those who were completing the course for a reason other than receiving CEs may not have wanted to complete the post-test. Another limitation is that we were unable to track the impact of this training on the professionals’ behavior, and subsequent child outcomes.

Implications for Future Professional Development

Many of the states significantly impacted by the opioid crisis have rural areas, often with limited direct access to educational resources available. Obtaining professional development, especially in more specialized topics is often challenging. Barriers to obtaining professional development need consideration. Web-based trainings, such as this one, offer an effective way to disseminate information to an array of disciplines across a wide area quickly. While they do not replace in-person training, our participants showed an increase in knowledge. Future projects should examine how to leverage online platforms to educate and provide an online learning collaborative for the workforce. In an area where the knowledge is emerging and often cutting edge, this kind of community could provide an efficient model to disseminate evidence-based practices. Future trainings should also consider the multi-disciplinary nature of the opioid crisis. Many others including mental health providers, case workers, nurse navigators, and physicians work with who work with families in addition to ECWs and substance use counselors.

Future Research

The initial literature review and the data collected provide many areas for future directions. First, more research is needed about the short- and long-term effects of in utero opioid exposure. Much of the existing research is old and may not reflect the current culture. Additionally, the older studies are mired with methodological and reporting flaws. For example, results must be interpreted with caveats due to the polysubstance use of the women included in the studies. Often the research does not follow neonates past infancy or children beyond preschool years. Our findings point to the perceived importance of understanding long-term effects that exposure has on learning, cognition, and mental health. In addition, rather than examining exposure in isolation, future research should include prospective longitudinal studies of child development and its relationship to parental opioid use and ACEs. We should track the number of youths served within early intervention, Head Start, and special education with in utero exposure histories. Researchers should follow children who were not exposed in utero but are witnesses to parental opioid use.

Research related to training and service delivery is also needed. Our participants’ scores on the knowledge measure improved. However, this instrument is new, which would benefit from validation studies. Another future direction would to be track outcomes of the children whose providers participated in a training to see if knowledge/awareness translates to skill use and whether the children benefit. Finally, those providing training should compare different delivery modalities to see which has the best outcomes.

Data Availability

Data and material may be requested to Andrea Witwer, andrea.witwer@osumc.edu.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Bowers, M., & Yehuda, R. (2016). Intergenerational transmission of stress in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of The American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 41, 232–244. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.247

Byrnes, J. J., Babb, J. A., Scanlan, V. F., & Byrnes, E. M. (2011). Adolescent opioid exposure in female rats: Transgenerational effects on morphine analgesia and anxiety-like behavior in adult offspring. Behavioural Brain Research, 218(1), 200–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2010.11.059

Byrnes, J. J., Johnson, N. L., Carini, L. M., & Byrnes, E. M. (2013). Multigenerational effects of adolescent morphine exposure on dopamine D2 receptor function. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 227(2), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-012-2960-1

Chaplin, T. M., & Sinha, R. (2013). Stress and parental addiction. In N. E. Suchman, M. Pajulo, & L. C. Mayes (Eds.), Parenting and substance abuse: Developmental approaches to intervention (pp. 24–43). Oxford University Press.

Clayton, R. R., Sloboda, Z., & Page, B. (2009). Reflections on 40 years of drug abuse research: Changes in the epidemiology of drug abuse. Journal of Drug Issues, 39(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260903900105.

Compton, W. M., Thomas, Y. F., Conway, K. P., & Colliver, J. D. (2005). Developments in the epidemiology of drug use and drug use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(8), 1494–1502. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1494.

Dasgupta, N., Creppage, K., Austin, A., Ringwalt, C., Sanford, C., & Proescholdbell, S. K. (2014). Observed transition from opioid analgesic deaths toward heroin. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 145, 238–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.005

Dolezal, T., McCollum, D., & Callahan, M. (2009). Hidden costs in health care: The economic impact of violence and abuse. The Academy on Violence and Abuse.

Edrees, H., Roley-Roberts, M. E., Nidey, N., Foci, F., Storts, M., Nightingale, B., Walton, J., Williams-Arya, P., Witwer, A., Real, J., Froehlich, T., & Weber, S. (2022). Online training of early childhood education professionals on developmental and behavioral sequelae of the opioid epidemic: Development, dissemination, and trainee satisfaction.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Fill, M. M. A., Miller, A. M., Wilkinson, R. H., Warren, M. D., Dunn, J. R., Schaffner, W., & Jones, T. F. (2018). Educational disabilities among children born with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0562

Finnegan, L. P. (1978). Management of pregnant drug-dependent women. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 311(1), 135–146.

Finnegan, L. P., Connaughton Jr, J. F., Kron, R. E., & Emich, J. P. (1975). Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Assessment and management. Addictive Diseases, 2(1–2), 141–158.

Freeman, R. C., Collier, K., & Parillo, K. M. (2002). Early life sexual abuse as a risk factor for crack cocaine use in a sample of community-recruited women at high risk for illicit drug use. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 28(1), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.1081/ADA-120001284.

Groundwork Ohio (2018). The impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in Ohio. https://www.groundworkohio.org/single-post/2018/03/16/The-Impact-of-Adverse-Childhood-Experiences-ACEs-in-Ohio

Hildyard, K. L., & Wolfe, D. A. (2002). Child neglect: Developmental issues and outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26(6–7), 679–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00341-1.

Hudak, M. L., & Tan, R. C. (2012). Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3212

Johnson, N. L., Carini, L., Schenk, M. E., Stewart, M., & Byrnes, E. M. (2011). Adolescent opiate exposure in the female rat induces subtle alterations in maternal care and transgenerational effects on play behavior. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00029”

Kaltenbach, K., & Jones, H. E. (2016). Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Presentation and treatment considerations. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 10(4), 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000207.

Koss, M. P. (1992). Somatic consequences of violence against women. Archives of Family Medicine, 1(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1001/archfami.1.1.53.

Kotelchuck, M., Cheng, E. R., Belanoff, C., Cabral, H. J., Babakhanlou-Chase, H., Derrington, T. M., & Bernstein, J. (2017). The prevalence and impact of substance use disorder and treatment on maternal obstetric experiences and birth outcomes among singleton deliveries in Massachusetts. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21, 893–902.

Larson, J. J., Graham, D. L., Singer, L. T., Beckwith, A. M., Terplan, M., Davis, J. M., Martinez, J., & Bada, H. S. (2019). Cognitive and behavioral impact on children exposed to opioids during pregnancy. Pediatrics, 144(2), e20190514.

Lynch, S., Sherman, L., Snyder, S. M., & Mattson, M. (2018). Trends in infants reported to child welfare with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Children and Youth Services Review, 86, 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.01.035.

Medrano, M. A., Hatch, J. P., Zule, W. A., & Desmond, D. P. (2002). Psychological distress in childhood trauma survivors who abuse drugs. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 28(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1081/ADA-120001278

Ohio Department of Health (2020). Ohio department of health releases new report showing county type breakdown of 2018 drug overdose deaths. https://odh.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/odh/media-center/odh-news-releases/odh-new-report-county-type-breakdown-2018-drug-overdose-deaths

Patrick, S. W., Schumacher, R. E., Benneyworth, B. D., Krans, E. E., Mcallister, J. M., & Davis, M. M. (2012). Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures. Jama. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.3951

PCSAO (2017). The children services mission; safety, permanency, and well-being (13th Edition). www.pcsao.org

Peisch, V., Sullivan, A. D., Breslend, N. L., Benoit, R., Sigmon, S. C., Forehand, G. L., Strolin-Goltzman, J., & Forehand, R. (2018). Parental opioid abuse: A review of child outcomes, parenting, and parenting interventions. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(7), 2082–2099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1061-0

Rosen, T. S., & Johnson, H. L. (1985). Long-term effects of prenatal methadone maintenance. NIDA Research Monography, 59(1), 73–83.

Saia, K. A., Schiff, D., Wachman, E. M., Mehta, P., Vilkins, A., Sia, M., Prince, J., Samura, T., DeAngelis, J., Jackson, C. V., Emmer, S. F., Shaw, D., & Bagley, S. (2016). Caring for pregnant women with opioid use disorder in the USA: Expanding and improving treatment. Current Obstetrics and Gynecology Reports, 5(3), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13669-016-0168-9

Schwerdtfeger, K. L., & Goff, B. S. N. (2007). Intergenerational transmission of trauma: Exploring mother–infant prenatal attachment. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20179.

Strauss, M. E., Andresko, M., Stryker, J. C., Wardell, J. N., & Dunkel, L. T. (1974). Methadone maintenance during pregnancy: Pregnancy, birth, and neonate characteristics. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 120(7), 895–900.

Suchman, N., Pajulo, M., Decoste, C., & Mayes, L. (2006). Parenting interventions for drug-dependent mothers and their young children: The case for an attachment-based approach. Family Relations, 55(2), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00371.x.

Thomas, Y. F. (2007). The social epidemiology of drug abuse. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(6), S141–S146.

Uebel, H., Wright, I. M., Burns, L., Hilder, L., Bajuk, B., Breen, C., Abdel-Latif, M. E., Feller, J. M., Falconer, J., Clews, S., Eastwood, J., & Oei, J. L. (2015). Reasons for rehospitalization in children who had neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2767

U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, Current Population Survey (CPS) (2018). October 1970 through 2017 https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_202.10.asp

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2019). Preschool and Kindergarten Enrollment https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cfa.asp

Van Baar, A. (1990). Development of infants of drug dependent mothers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 31(6), 911–920. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb00833.x.

Welton, S., Blakelock, B., Madden, S., & Kelly, L. (2019). Effects of opioid use in pregnancy on pediatric development and behaviour in children older than age 2: Systematic review. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien, 65(12), e544–e551.

Acknowledgements

The team would like to thank Felicia Foci, Brooke Nightingale, and Michael Storts for their contributions to the project to which this manuscript is based.

Funding

This project was funded by funded by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau Grant Nos. T73MC24481 & T73MC00032.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MER-R: wrote and edited the introduction with the assistance of JT, the method and results with HE, SW, and RR. MER-R: supervised RR and JT in conducting the analyses. AW, JW, and MER-R: co-wrote the discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

This project was IRB reviewed by The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center IRB and was approved.

Consent to Participate

All participants in this study provided informed consent prior to participation.

Consent for Publication

All data published are done so in aggregate and de-identified. Participants consented to use of their data in presentations and publications.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Roley-Roberts, M., Edrees, H., Thomas, J. et al. Impact of an Asynchronous Training for the Early Intervention and Childcare Workforce Addressing the Developmental Impact of the Opioid Crisis on Young Children. Matern Child Health J 27, 1361–1369 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03679-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03679-4