Abstract

Objectives

To assess emergency preparedness (EP) actions in women with a recent live birth.

Methods

Weighted survey procedures were used to evaluate EP actions taken by women with a recent live birth responding to an EP question assessing eight preparedness actions as part of the 2016 Tennessee Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System (PRAMS) survey. Factor analysis was used to group preparedness actions.

Results

Overall, 82.7% [95% Confidence Interval (CI) 79.3%, 86.1%] of respondents reported any preparedness actions, with 51.8% (95% CI 47.2%, 56.4%) completing 1–4 actions. The most common actions were having supplies at home (63.0%; 95% CI 58.5%, 67.4%), an evacuation plan for children (48.5%; 95% CI 43.9%, 53.2%), supplies in another location (40.2%; 95% CI 35.6%, 44.7%), and a communication plan (39.7%; 95% CI 35.1%, 44.2%). Having personal evacuation plans (31.6%; 95% CI 27.3%, 36.0%) and copies of documents in alternate locations (29.3%; 95% CI 25.0%, 33.5%) were least common. Factor analysis yielded three factors: having plans, having copies of documents, and having supplies. Specific preparedness actions varied by education and income level.

Conclusions for Practice

Most Tennessee women (about 8 in 10 women) with a recent live birth reported at least one EP action. A three-part EP question may be sufficient for assessing preparedness in this population. These findings highlight opportunities to improve public health education efforts around EP.

Significance

What is known on this subject? Current emergency preparedness guidelines recommend making emergency plans, building a disaster supplies kit, and having access to important personal documents.

What this study adds? A majority of women (about 8 in 10) with a recent live birth had made at least some emergency preparations. Specific preparedness actions varied by education and income level. This highlights an opportunity to develop tailored public health emergency preparedness messaging according to population needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Natural disasters, including tornadoes, floods, and wildfires, are unforeseen incidents whose stressors can be mitigated with emergency preparedness efforts (Cannon, 2008). Since 2010, Tennessee (TN) has averaged two major disaster declarations per year; most have been for severe storms, tornadoes and flooding (FEMA, Declared Disasters, ). While earthquakes are not a common occurrence in Tennessee, West Tennessee, representing approximately a third of the state’s geography, sits along the New Madrid Fault Line, along with seven other states. A 2009 geological study estimated that a significant earthquake in that region would impact at least 20 Tennessee counties and potentially include up to 86,000 casualties across the affected states (Elnashai et al., 2009). After an event of this magnitude, damage to local infrastructure, including to bridges, roadways, and schools, and delays in delivery of aid are anticipated. In March 2020, several counties in Tennessee were impacted by an overnight outbreak of 13 tornadoes, which killed 24 people and caused over $1.6 billion in property damage, including homes, schools, grocery stores, and designated emergency shelters (NESDIS, 2020). One week after the tornadoes, many were still without electricity. Adding to the complexity of the post-disaster environment, in the same month, Tennessee identified its first case of COVID-19 and announced statewide Safer-at-Home orders. (State of Tennessee Executive Order No. 17, 2020; State of Tennessee Executive Order No. 27, 2020). Both earthquakes and tornadoes occur with minimal warning, and can have significant impacts, highlighting the need for households to be self-sufficient until local resources can be restored.

Current preparedness guidelines include making emergency plans, building a disaster supplies kit, and having access to important personal documents (FEMA, Make a Plan, 2021; FEMA, Build a Kit, 2020; FEMA, Financial Preparedness, 2021). Emergency plans include knowing how to maintain and protect family health and wellness; discussing ways to communicate with family, friends, and caregivers; practicing way to stay calm in an emergency; and how to stay informed by finding sources of reliable health and emergency information. (CDC, Plan Ahead, 2021) Preparedness activities might include gathering food, water, and medical supplies to last at least 72 h, preparing an emergency supply of prescription medications, learning self-help and life-saving skills to use during an emergency, preparing for power outages, and collecting and protecting important documents and medical records. (CDC, Take Action, 2021).

Pregnant women, postpartum women, and infants are cited as at-risk individuals who may be affected by an emerging public health threat in the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advancing Innovation Act (PAHPAI) of 2019. Pregnancy increases the risk of adverse outcomes from infectious diseases and introduces additional considerations for treatment of disaster-related injuries. Environmental disasters may increase the risk of pregnancy loss, preterm birth, and low birth weight infants among exposed pregnant women. (American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, 2017). Households with infants and young children may experience additional health risks during public health emergencies, as infants and children may be more susceptible to the effects of a disaster (Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advancing Innovation Act of 2019; American Academy of Pediatrics, 2015). Pregnant women, postpartum women, and infants may experience interruptions in the delivery of healthcare services and loss of access to supplies—such as supplemental infant formula—in the setting of damaged infrastructure and supply chains. Adoption of preparedness behaviors among women in TN with infants or young children is unknown.

The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) is a state- and population-based surveillance system designed to monitor selected self-reported behaviors and experiences before, during, and after pregnancy among women who have had a recent live birth (Shulman et al., 2018). In 2016, TN PRAMS was one of two jurisdictions that included the new and optional eight-part emergency preparedness question. The authors sought to assess emergency preparedness behaviors in women with a recent live birth.

Methods

Each month, women with a live birth in the past 2–6 months were randomly sampled from provisional birth certificate data. The participants were then mailed the PRAMS Survey up to three times. If a woman did not respond to the mailed survey, she was then contacted by phone to complete the survey (Shulman et al., 2018). Consent was implied if the woman returned the completed survey by mail; for surveys completed by phone, verbal consent was obtained. This project was approved by the Tennessee Department of Health and CDC Institutional Review Boards.

In 2016, TN PRAMS included an eight-part emergency preparedness question, pretested by the CDC, to assess eight distinct preparedness actions (CDC, 2016). Respondents were included in the analysis if they answered at least one part of the emergency preparedness question:

-

(a)

I have an emergency meeting place for family members (other than my home).

-

(b)

My family and I have practiced what to do in case of a disaster.

-

(c)

I have a plan for how my family and I would keep in touch if we were separated.

-

(d)

I have an evacuation plan if I need to leave my home and community.

-

(e)

I have an evacuation plan for my child or children in case of disaster (permission for day care or school to release my child to another adult).

-

(f)

I have copies of important documents like birth certificates and insurance policies in a safe place outside of my home.

-

(g)

I have emergency supplies in my home for my family such as enough extra water, food, and medicine to last for at least three days.

-

(h)

I have emergency supplies that I keep in my car, at work, or at home to take with me if I have to leave quickly.

Data from the Tennessee birth certificate included maternal age, maternal education, marital status, urban or rural residence, maternal race, and participation in Women Infants and Children (WIC) services during pregnancy. Age was collapsed into five categories: less than 20 years, 20–24 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, and 35 years or greater. Race was categorized as White/Non-Hispanic, Black/Non-Hispanic, and Other (including Hispanic ethnicity of any race, Asian, more than one race/ethnicity, or other race). Education was categorized as less than high school diploma, high school diploma or General Educational Development (GED), some college, and college degree or greater. Information obtained from PRAMS included total income and family size. Total income captured the reported household income 12 months prior to the birth, and family size was defined as number of individuals living on the total income in the 12 months prior to the live birth. A variable categorizing income as a percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) was developed from total income and family size, compared to the January 2016 poverty guidelines issued by the Federal Register of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS, 2016). Four FPL groups are reported as less than or equal to 100%, 101–185%, 186–300%, and greater than 300% FPL, consistent with federal programing eligibility (DHHS, 2016). Data regarding pregnancy intention, pre-existing hypertension, and pre-gestational diabetes are collected as part of PRAMS. Urbanicity (urban or rural) was established by county of residence. Three distinct regions (East, Middle, and West) were defined based on county of residence within the Grand Divisions of Tennessee (State of Tennessee, Tennessee Code Annotated § 4-1-201; § 4-1-202; § 4-1-203; § 4-1-204). The three regions are distinct, with differences based on regional topography and potential natural hazards such as severe weather, earthquakes, and flooding.

The PRAMS sample was weighted to be representative of all women with a recent live birth in the state by accounting for sampling stratification, nonresponse, and noncoverage. All reported percentages were weighted.

Factor analysis was performed using the maximum likelihood estimate and varimax rotation, to assess underlying factors among the eight emergency preparedness actions. All analyses were conducted using survey procedures in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

In 2016, 1743 women were sampled and contacted for TN PRAMS participation, and 784 responded (weighted response rate, 48%). Of the 784 respondents to the 2016 TN PRAMS Survey, 745 (95.0%) answered at least one part of the eight-part emergency preparedness question. After weighting, this represented 74,596 women with a recent live birth in 2016. The following results are based upon the weighted estimate of 74,596 women. Weighted demographics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Overall, 82.7% (95% CI 79.3%, 86.1%) of respondents reported at least one preparedness action, with 51.8% (95% CI 47.2%, 56.4%) completing 1–4 actions, and 8.3% reporting all eight actions (data not shown). The most commonly reported actions were having supplies at home (63.0%; 95% CI 58.5%, 67.4%), having an evacuation plan for children (48.5%; 95% CI 43.9%, 53.2%), having supplies ready in case of evacuation (40.2%; 95% CI 35.6%, 44.7%), and having a communication plan (39.7%; 95% CI 35.1%, 44.2%). One third of respondents reported having practiced their disaster plans (34.3%; 95% CI 29.8%, 38.7%) or having a designated place to meet after the disaster (33.4%; 95% CI 28.9%, 37.8%). The least reported actions were having an evacuation plan for themselves (31.6%; 95% CI 27.3%, 36.0%) and having copies of documents in alternate locations (29.3%; 95% CI 25.0%, 33.5%) (Table 2).

Factor analysis grouped the emergency preparedness actions into three factors. The first factor (Having plans) captured women that responded yes to at least one of the actions: emergency meeting place, practiced what to do, plan to keep in touch, plan for themselves to evacuate, or an evacuation plan for their children. The second factor (Having copies) included women who responded yes to having copies of important documents, and the third factor (Having supplies), included women that had emergency supplies for at least three days and/or had emergency supplies prepared if they had to leave quickly. By factor, more than half of respondents reported having emergency preparedness plans (61.8%; 95% CI 57.4%, 66.1%) or supplies (65.5%; 95% CI 57.7%, 66.5%), while 29.0% (95% CI 23.5%, 31.5%) reported having copies of documents.

By maternal education level, the percentage of women reporting having plans was significantly greater among women with high school diploma or general educational development (GED) level of education (77.2%; 95% CI 69.1%, 85.4%) compared to women with a college degree or greater level of education (58.3%; 95% CI 50.3%, 66.3%). The percentage of women reporting having documents was greater among women with high school diploma or GED (37.0%; 95% CI 27.5%, 46.6%) compared to women with a college degree or greater level of education (19.4%; 95% CI 13.1%, 25.7%), though confidence intervals overlapped.

By income, the percentage of women reporting having plans was greater among women at ≤ 100% FPL (73.5%; 95% CI 66.4%, 80.6%) compared to women with income over 350% FPL (58.1%; 95% CI 49.0%, 67.3%), though confidence intervals overlapped. The percentage of women reporting having documents was greater among women at ≤ 100% FPL (38.8%; 95% CI 30.7%, 46.9%) compared to women with income over 350% FPL (21.8%; 95% CI 14.0%, 29.6%).

There were no statistically significant differences in having plans or having documents by age, race/ethnicity, parity, and pre-existing conditions, urbanicity, and geographic region (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences in having supplies among women by any of the included demographic characteristics.

Discussion

A majority (82.7%) of Tennessee women with a recent live birth in 2016 had undertaken at least one of the preparedness actions assessed; however, 17% had not taken any of these specific actions. They may have prepared in other ways not assessed in by the PRAMS emergency preparedness question. Specific preparedness actions varied by education and income level. These findings highlight opportunities to improve public health education efforts around emergency preparedness.

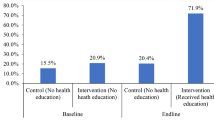

Over 80% of women had completed at least one preparedness action, and just over half of respondents had completed up to four actions. To our knowledge, Hawaii was the only other PRAMS site to adopt the emergency preparedness question, with very similar findings (Strid et al., 2022). In Hawaii, 79.3% of women had undertaken at least one preparedness action, and 11.2% completed all eight actions. Factor analysis also yielded similar results, with 59.8% having made any plans, 66.8% reported having supplies, and 31.8% reported having copies of important documents. As in Tennessee, lower income women in Hawaii were more likely to have copies of important documents than women of higher incomes.

Having taken some emergency preparedness actions may make respondents feel more prepared than they actually are. A study of parents of children with developmental disabilities found that parents who self-rated themselves as “very well prepared” had completed an average of only 4.7 of the 11 action steps assessed in that study (Wolf-Fordham et al., 2015). In the present study, more than two-thirds of respondents reported having made at least one type of emergency preparedness plan, but the rigor of those plans was not assessed. We also observed preparedness actions did not align across factor domains. For example, while 40% of respondents had emergency supplies ready if they needed to leave quickly, only 32% reported having an evacuation plan for themselves, and 21% had both an evacuation plan and supplies that could be taken quickly in case of an evacuation.

Having plans and having supplies were more common than having copies of important documents stored in a safe place away from home. Less than one-third of women reported having copies of important documents stored in a safe place away from the home, and women below 100% of the federal poverty level were almost twice as likely to report having documents stored away from the home as women at or above 350% of the poverty level. We are unable to determine the reasons for these findings based on available data. Practices around safe storage of important documents may vary depending on need to have the documents accessible at home for frequent use, accessibility to a safe physical storage (e.g., deposit box), use of electronic storage options for documents (e.g., cloud storage technology), availability of trusted individuals (e.g., relatives) to keep the documents, and the means to replace documents if lost or damaged.

In this analysis, the percentage of women completing preparedness actions related to plans and to documents was generally greater among women at lower income and education levels compared to women at higher income and education, though confidence intervals between many categories overlapped. This finding is somewhat consistent with that from the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), in which similar questions regarding general emergency preparedness were added by the state. Among the BRFSS sample of randomly selected non-institutionalized adults, respondents with incomes greater than $25,000 annually were more likely to have adequate supplies, but there was an inverse association between having a written disaster plan and income (TN BRFSS, 2015). Reasons for these observed differences in emergency preparedness actions by income level are not well understood but may include differences in perception of how preparedness may or may not mitigate impacts of disaster, differences in previous exposure to disasters, and differences in the accessibility to preparedness messaging (Rivera, 2020). Additionally, it is not clear if women with resources may be taking actions perceived as requiring less planning, such as finding lodging at a hotel or sheltering in the homes of friends or relatives. Based upon the small unweighted sample size, we were not able to stratify at the county level, but analyses at the Grand Division level and urban/rural residence did not yield any statistically significant differences in emergency preparedness actions.

Data from this analysis suggest that having supplies is the most common preparedness action taken by women with a recent live birth in Tennessee, and this action represents the minimum level of preparedness specified in guidelines. These data suggest an opportunity to raise awareness of other components of preparedness. Some natural events, such as tornadoes or earthquakes, offer no advance notice. In the days immediately following these events, access to resources may be limited for all individuals if roads are blocked or damaged, or stores are without electricity. Other natural events, such as hurricanes, may offer more advance preparation time, but can have a similar impact on local utilities and resources. The list of actions might be condensed into the three factors identified in this analysis—having plans, having copies, and having supplies—to simplify the list and to bring plans and copies forward as equal parts of preparedness planning. More information is needed regarding why certain emergency preparedness actions may be more commonly practiced and how EP messages are best received by women. Similarly, the PRAMS emergency preparedness question might benefit from simplification into fewer parts, which may in turn increase the use of this question by jurisdictions and potentially avoid reductions in participant response rates associated with longer questionnaires.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, the overall weighted response rate of 45% in Tennessee falls below the national PRAMS response rate of 54%; however, very few women were excluded from the analysis based on non-response to the emergency preparedness question. Second, PRAMS collects information from women with a recent live birth, and the responses do not represent those of all women with infants and young children. Third, while PRAMS methodology accounts for non-response, estimates of preparedness among women with a recent live birth in Tennessee may be different among non-respondents. Fourth, data for income had a higher percentage of missing values (6.4% of unweighted data) compared to other characteristics. Finally, there are limitations to the module used to assess emergency preparedness. It is unclear how PRAMS participants responded to questions if they had taken similar actions, but not those mentioned specifically in the question. For example: having three days of groceries on hand versus a supply of food items stored specifically as an emergency stash or storage of hard copy documents versus use of cloud storage and knowledge of how to replace lost or destroyed documents. There may also be other preparedness actions undertaken by this population not measured in the PRAMS emergency preparedness question, for example, child evacuation plans beyond those related to release from school to another adult. Additionally, it is possible other members of the household were responsible for preparedness actions, and respondents were not aware of all actions that had been taken.

Conclusions for Practice

Health departments might improve emergency preparedness education and communication efforts by emphasizing all three factors—having plans, having copies, having supplies—in messaging about emergency preparedness. While national emergency preparedness resources exist, they may also consider highlighting preparedness needs unique to postpartum and lactating women, as well as those with infants and young children, similar to call-outs specific to populations at risk for adverse health outcomes in disasters, such as for the elderly (FEMA, Seniors, 2020). Potential methods for disseminating emergency preparedness messaging include distribution or posting of informational materials at local health department clinics, obstetric or pediatric providers’ offices, publications or social media for parents, and community venues frequented by families with children.

Overall survey length is considered when deciding whether to include additional questions in the PRAMS survey, and is associated with response rate (Sahlqvist et al., 2011, Guo et al., 2016). Results of the factor analysis may also indicate that when survey length is limited, that the PRAMS emergency preparedness question might be reformatted into three parts to attain more general information in preparedness behaviors.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, AMM. The data are not publicly available based upon the data sharing agreement between Tennessee Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Code Availability

Code for data cleaning and analysis is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). (2015). Disaster preparedness advisory council and committee on pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatrics, 136, e1407. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3112

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2017). Hospital disaster preparedness for obstetricians and facilities providing maternity care. Committee Opinion No. 726. Obstetrics & Gynecology., 130, e291–e297.

Cannon, T. (2008) Reducing People’s Vulnerability to Natural Hazards: Communities and Resilience. Research Paper 2008/034. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/rp2008-34.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Take Action. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved June 23, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/prepyourhealth/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Plan Ahead. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved June 23, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/prepyourhealth/planahead/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). PRAMS Phase 8 Topic Reference Document. 2016; Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/prams/pdf/questionnaire/Phase-8-Topics-Reference_508tagged.pdf

Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). (2016). Annual update of the HHS poverty guidelines. Federal Register, 81(15), 4036–4037.

Elnashai, A. S., Jefferson, T., Fiedrich, F., Cleveland, L. J., Gress, T (2009). Impact of New Madrid Seismic Zone Earthquakes on the Central USA. Mid-America Earthquake Center Report 09-03. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from http://mae.cee.illinois.edu/publications/reports/Report09-03.pdf

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Build A Kit. United States Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved December 7, 2020a, from https://www.ready.gov/kit

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Seniors. United States Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved December 7, 2020b, from https://www.ready.gov/seniors

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Plan Ahead. United States Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved June 23, 2021a, from https://www.ready.gov/plan

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Financial Preparedness. United States Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved June 23, 2021b, from https://www.ready.gov/financial-preparedness. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Declared Disasters. United States Department of Homeland Security. https://www.fema.gov/disasters/disaster-declarations?field_dv2_state_territory_tribal_value=TN&field_year_value=All&field_dv2_declaration_type_value=DR&field_dv2_incident_type_target_id_selective=All&page=0. Accessed December 7, 2020.

Guo, Y., Kopec, J. A., Cibere, J., Li, L. C., & Goldsmith, C. H. (2016). Population survey features and response rates: A randomized experiment. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 1422–1426. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303198

National Environmental Satellite Data and Information Service (NESDIS). (2020, March). Deadly Tornadoes Tear Through Tennessee. U.S. Department of Commerce. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/content/deadly-tornadoes-tear-through-tennessee

Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advancing Innovation Act of 2019. In. Sen. Burr RR-N, trans. 116 ed2019. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/s1379/BILLS-116s1379enr.pdf

Retrieved November 3, 2020, from https://www.ready.gov.

Rivera, J. D. (2020). The likelihood of having a household emergency plan: Understanding factors in the US context. Natural Hazards (dordrecht, Netherlands). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04217-z

Sahlqvist, S., Song, Y., Bull, F., et al. (2011). Effect of questionnaire length, personalisation and reminder type on response rate to a complex postal survey: Randomised controlled trial. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-62

Shulman, H. B., D’Angelo, D. V., Harrison, L., Smith, R. A., & Warner, L. (2018). The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): Overview of design and methodology. American Journal of Public Health, 108, 1305–1313. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304563

State of Tennessee. Tennessee Code Annotated. § 4-1-202. Retrieved February 22, 2021, from https://casetext.com/statute/tennessee-code/title-4-state-government/chapter-1-general-provisions/part-2-grand-divisions-and-state-capital/section-4-1-202-eastern-grand-division. Published 2020b

State of Tennessee. Tennessee Code Annotated. § 4-1-203. Retrieved February 22, 2021, from https://casetext.com/statute/tennessee-code/title-4-state-government/chapter-1-general-provisions/part-2-grand-divisions-and-state-capital/section-4-1-203-middle-grand-division. Published 2020c

State of Tennessee. Tennessee Code Annotated. § 4-1-204. Retrieved February 22, 2021, from https://casetext.com/statute/tennessee-code/title-4-state-government/chapter-1-general-provisions/part-2-grand-divisions-and-state-capital/section-4-1-204-western-grand-division. Published 2020d

State of Tennessee Executive Order No. 17 (2020a). Retrieved December 7, 2020a, from https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/pub/execorders/exec-orders-lee17.pdf. Published 2020

State of Tennessee Executive Order No. 27 (2020b) Retrieved December 7, 2020b, from https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/pub/execorders/exec-orders-lee27.pdf. Published 2020

State of Tennessee. Tennessee Code Annotated. § 4-1-201. Retrieved February 22, 2021, from https://casetext.com/statute/tennessee-code/title-4-state-government/chapter-1-general-provisions/part-2-grand-divisions-and-state-capital/section-4-1-201-grand-divisions Published 2020a

Strid, P., Fok, C. C. T., Zotti, M., et al. (2022). Disaster preparedness among women with a recent live birth in Hawaii, results from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2016. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 16(5), 2005–2014. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.274

Tennessee Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2015. State Added Codebook 2015. Office of Population Health Surveillance, Division of Population Health Assessment, Tennessee Department of Health. Retrieved July 10, 2020, from https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/documents/brfss/State%20Added%20Report%202015.pdf

Wolf-Fordham, S., Curtin, C., Maslin, M., Bandini, L., & Hamad, C. D. (2015). Emergency preparedness of families of children with developmental disabilities: What public health and safety emergency planners need to know. Journal of Emergency Management, 13(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2015.0213

Funding

This project was funded through Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Grant No. 1U01DP006245.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMM performed statistical analysis and contributed to writing of the manuscript; RRG conceived and designed the analysis and contributed to writing of the manuscript; LH conducted statistical analysis; PS conceived and designed the analysis and contributed to writing of the manuscript; UL participated in data collection and contributed to writing of the manuscript; SRE conceived and designed the analysis and contributed to writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Ethical Approval

This project was approved by the Tennessee Department of Health and CDC Institutional Review Boards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the analysis.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors have indicated that this study data has been presented previously as an abstract at the 2020 CityMatCH Leadership and MCH Epidemiology Conference on September 16, 2020.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, A.M., Galang, R.R., Hall, L.E. et al. Emergency Preparedness in Tennessee Women with a Recent Live Birth. Matern Child Health J 27, 1335–1342 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03649-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03649-w