Abstract

Objective

To estimate the relationship between household income and child health outcomes for male and female children, aged 0–5 years, in rural Pakistan.

Method

The study uses 2014 round of Pakistan Rural Household Panel Survey (PRHPS) and regression analyses to estimate the relationship between household income and child health outcomes for male and female children in rural Pakistan.

Results and Policy Implications

We find that increase in income is associated with an increase in child weight-for-age and weight-for-height z-scores, and reduction in the likelihood of a child being underweight or wasted. However, our results suggest that these gains associated with an increase in income are greater for male children as compared to female children. These differences in income-nutrition gradient can be explained by the gender-differences in consumption of health inputs (e.g., food intake, vaccinations, and nutritional supplements) associated with an increase in income. Our results indicate the need for policy instruments that can encourage an equitable resource allocation within households.

Significance

This study documents the gender bias in income-health relationship for children in rural Pakistan. Our results imply that interventions that target poverty alleviation at the household level may not have equitable impacts on all members of the household because of possible ‘son-preference’. This suggests that there is a need to design gender-sensitive interventions to ensure that improvements in nutritional outcomes are shared across genders within households.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Undernutrition poses a major development challenge for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). It has been linked to high mortality rates among children; approximately half of the deaths of children under the age of 5 years can be attributed to under nutrition (Black et al., 2008; UNICEF, 2019). Poor nutrition starts in-utero and can result in low birth weight and an increased susceptibility to communicable and non-communicable diseases (Pena & Bacallao, 2002). Children who are undernourished are often stunted, wasted, or underweight. Low weight-for-height (wasting) signals acute growth disturbance, low height-for-age (stunting) reflects long term growth faltering, and low weight-for-age (underweight) reflects a combination of short- and long-term effects (Marcoux, 2002). Such children are also more likely to experience poor cognitive development and reduced productivity in adulthood (WHO, 2020).

The relationship between income and child health, and the mechanisms through which income and child health are related are an important policy-related issue that has been the focus of a large empirical literature (e.g., Behrman & Deolalikar 1987; Burgess et al., 2004; Case et al., 2002; Currie & Stabile, 2003; Currie et al., 2007; Frijters et al., 2005; Smith & Haddad, 2002). Furthermore, literature has documented several dimensions of inequitable intrahousehold resource allocation between male and female children, especially in the context of South Asia, (Abdullah & Wheeler, 1985; Behrman, 1988a, 1988b; Cowan & Dhanoa, 1983; Miller 1997; Gupta, 2016; Javed & Mughal, 2019; Jayachandran & Pande, 2017). However, little attention has been given to understanding differences in the income-nutrition gradient across male and female children, especially in a developing country context. In this paper, using Pakistan as a case, we investigate the relationship between income and child health outcomes and if higher income translates into increased consumption of an array of health inputs for both male and female children.

Income is often linked to poor health outcomes, with studies suggesting ‘wealthier is healthier’ (Smith & Haddad, 2002). Social scientists often point to the “gradient in health status”, which refers to “the phenomenon that relatively wealthier people have better health and longevity” and argue that this gradient is “evident throughout the income distribution” (Case et al., 2002). For instance, using data on children from the US National Health Interview Survey, Case et al. (2002) provides evidence of a significant positive income gradient, where children in poorer families have worse health outcomes as compared to those from richer families with this relationship becoming more pronounced as children grow older (Case et al., 2002). Similarly, in another study focusing on Canadian children, Currie and Stabile (2003) find that the income of a family is negatively related to being in poor health and the income gradient increases with child age. This income-nutrition gradient holds when an increase in income is accompanied by an increase in consumption of an array of health inputs including better caloric intake and dietary diversity (Agrawal et al, 2019; Black et al., 2008; Mahmudiono et al., 2017; Melaku et al., 2018; Moges et al., 2015; Nnyepi, 2007; Rah et al., 2010; Vella et al., 1994).

Yet, other studies find that income does not lead to improved health outcomes. For instance in studies focusing on British children, Burgess et al (2004) and West (1997) find that the gradient between family income and child health is very small and the slope of the gradient does not increase with the age of the child (Burgess et al., 2004; West, 1997). Similarly, using a sample of 13,000 children in England, Currie et al (2007) find that while there is a family income gradient in child health, the size of the gradient is very small. Other studies drawing on panel data across countries, also do not find strong evidence that supports the link between income and health outcomes (Adams et al., 2003; Frijters et al., 2005; Meer et al., 2003).

The contribution of this paper to this above-mentioned literature is twofold. First, this paper contributes to the literature by estimating the income-nutrition gradient for male and female children, aged 0–5 years, in rural Pakistan. While the literature has documented instances of intrahousehold gender inequality in South Asia in related dimensions, such as height advantage for first-born sons (Behrman, 1988a; Jayachandran & Pande, 2017), participation in household decision-making (Javed & Mughal, 2019), and voting (Cheema et al., 2022), the differences in income-nutrition gradient across genders within households are not documented. Second, the paper estimates the relationship between income and health inputs for both male and female children to understand the mechanisms that may underlie the gradient and the gender differences in the gradient.

We find that while increases in income are associated with betterment in several child health outcomes, the gains are consistently greater for male children as compared to female children. These differences in income-nutrition gradient between boys and girls can be explained through inequality in intra-household resource allocation. Indeed, we find that gains associated with increased income in terms of intake of individual food items, vaccines and vitamin A supplements are greater for boys as compared to the girls. This finding with respect to income-nutrition differences among male and female children is especially interesting, as currently little work as has been done to document these gendered income-nutrition patterns.

Data and Methods

This paper uses the data from the 2014 round of Pakistan Rural Household Panel Survey (PRHPS). PRHPS is a panel survey from 2012 to 2014 that collected information from 1876 rural households in three provinces (Sindh, Punjab, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) of Pakistan (IFPRI, 2017). However, information on child nutritional outcomes and food intake are collected for the 2014 round specifically. Therefore, we use the 2014 wave of the PRHPS data for our analysis.

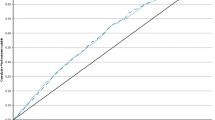

Table 1 describes the data and Table 2 provides summary statistics. Height and weight of about 900 children below or equal to the age of 5 years was measured by the survey team. Height-for-age (HAZ), weight-for-age (WAZ) and weight-for-height (WHZ) z-scores were calculated from these height and weight measurements based on the World Health Organization’s child growth standards (WHO, 2006). Outcome variables, Stunted, Underweight and Wasted, are dummy variables equal to 1 if HAZ, WAZ and WHZ are less than − 2, zero otherwise (using the WHO, 2006). In our sample, 43%, 41% and 21% of the children are Stunted, Underweight and Wasted, respectively. Incidence of Stunted, Underweight and Wasted children is at 48%, 43% and 21% for boys and 38%, 38% and 20% for girls, respectively. Pairwise t-tests suggest that means of Stunted and Underweight are statistically different (at 1% level of significance) between male and female children, with burden of undernutrition more on male children in rural Pakistan. Means of Wasted are statistically indifferent. We plot the incidence of the three anthropometric outcomes against quintiles of household income (Fig. 1). From Fig. 1, the relationship between income and child anthropometric outcomes is not entirely clear.

Annual household income is calculated as household’s per capita consumption expenditure (including expenditures on food, electricity, communication, transport, health, schooling, clothes other, etc.) aggregated at the annual level. This annual consumption expenditure, which we refer to as income in rest of the manuscript, is divided by the number of household members to obtain per capita yearly income of the household. In our sample, the mean per capita income is Rs. 20,986 (about $210 according to PKR-USD exchange rate in 2014). Therefore, an average household in our sample earns less than $2 a day. Other important variables included in the analysis are mother’s education levels, father’s education levels, child’s age and gender, age of the household head and region of residence.

The survey also includes information on the number of food items a child (of ≤ 5 years of age) consumed in the last 24 h. This information was collected from the mothers of the children. We use this information to develop the variable, Child Food Intake, which is a Guttman scale of number of food items (including cereals, meat, milk, eggs, and pulses). This variable is used to reflect dietary quality/diversity of children in the household. Mean of Child Food Intake is 1.16 items with 0 being the minimum and 5 being the maximum.Footnote 1 Means for individual items are also presented in Table 2. 7% of the children consumed meat (poultry, fish, beef, mutton or lamb) in the last 24 h. This average consumption is 52% of for milk products (ghee, butter, yogurt), 9% for pulses, 30% for cereals (rice, wheat, maize, semolina etc.) and 14% for eggs.

Consumption of Vaccines and Vitamin A Supplements could be further mechanisms (health inputs) that may affect income-nutrition relationship and are included in the analysis. Children are given an average of 8.89 vaccinations (including OPV, Pentavalent vaccines, Pneumococcal vaccines, BCG vaccine, and measles vaccinations) with a minimum of 5 and maximum of 13. 15% of the children received a Vitamin A Supplement in the last two weeks of the survey.

For empirical analysis, we use several econometric models to understand income-nutrition gradient in rural Pakistan. First, we use OLS regressions to estimate the relationship between income and nutritional outcomes such as HAZ, WAZ, and WHZ. Then, we use Probit regressions to investigate if children in poorer households are more likely to be stunted, underweight and wasted. Furthermore, we use Probit and Negative Binomial regressions to estimate the impact on health inputs, to investigate which of the mechanisms potentially explain the underlying income-nutrition gradient.

Following Brown et al. (2019) and Currie et al. (2007), we introduce other sources of heterogeneity in terms of household-level and individual-level characteristics that can be expected to enhance power for predicting child health outcomes. We run several econometric regressions of the following form:

where \({y}_{ij}\) is (a) child anthropometric outcomes of the child i in household j or (b) health inputs (food intake, vaccinations, supplements) consumed by children (aged ≤ 5 years) of household j. Functional form of the regression, \(f\left(.\right)\), depends on structure of the outcome variable. For example, for child anthropometric outcomes that are standardized indices, linear regressions are used to estimate the relationship between child health and income. However, Poisson and Probit models are used when outcome variables are count or indicator variables, respectively.

\(Incom{e}_{j}\) is natural log of yearly per capita household expenditure. \({X}_{j}\) control for household-level variables, e.g., age and gender of household head and district of residence and \({Z}_{ij}\) control for individual-level variables like child’s age and gender and education levels of child’s father and mother. The district of residence fixed effects control for unobservable district-level characteristics (e.g., the unobserved quality of child or maternal health services in a district) that could be correlated with incomes as well as outcome variables.

These regressions are estimated for the full sample, as well as separately for boys and girls within the households. Wald tests are conducted to test the significance of differences in the income-nutrition gradient across boys and girls within households. Standard errors are clustered at the household-level to control for intra-household correlation in errors.

Results

Table 3 shows the results for the linear regression with HAZ, WAZ, and WHZ as dependent variables. In Column 1, Table 3, we provide results for the full sample. We find no significant relationship between HAZ and Per Capita Income of households. In column 2 and 3 of Table 3, we provide results disaggregated by gender of the children. Again, for HAZ, we do not find a statistically significant positive relationship between income and HAZ in our disaggregated regressions.

For the Weight-for-Age regressions, we find that a log-point increase in Per Capita Income is associated with an increase in WAZ scores of 0.357, statistically significant at 1% level of significance (p-value < 0.01). This coefficient is 0.470 for boys, statistically significant at 5% (p-value < 0.05), and 0.171 for girls, not statistically significant at conventional levels (Table 3, columns 2 and 3). We observe a similar pattern of relationship between income and WHZ scores. One log-point increase in per capita income is associated with increase in WHZ score of 0.40, statistically significant at 5% level of significance (p-value < 0.05). This coefficient is 0.427 for boys, statistically significant at 5% (p-value < 0.05) level of significance, and 0.266 for girls, not statistically significant at conventional levels (Table 3, columns 2 and 3).Footnote 2 This difference in magnitude of income-nutrition gradient among boys and girls suggests that the gains from income in terms of nutrition may not be equally dispersed between different members of the households and point towards inequitable intra-household allocation of resources.

Table 4 provides the elasticities for the relationship between income and incidence of Stunted, Underweight and Wasted. Again, consistent with the results in Table 3, we find no significant relationship between income and stunting outcome. However, for Underweight outcome, we find that a 10% increase in Per Capita Income is associated with a reduction in the likelihood of a child being underweight by 1.8% (statistically significant at 10% level of significance). This elasticity is − 0.161 and − 0.091 for boys and girls (not statistically significant at conventional levels), respectively. Furthermore, we find that a 10% increase in Per Capita Income is associated with a 4.4% reduction in the likelihood of being Wasted. This elasticity is − 0.416 for boys (statistically significant at 10% level of significance) and − 0.342 for girls (not significant at conventional levels. Again, we observe that the magnitude of coefficients for boys are greater than that of girls, but the magnitude of difference is less than what we observed in Table 3.

To understand the mechanisms behind the gradient between income and nutrition, we investigate the potential of an increase in income in improving dietary intake of children, vaccination adoption and vitamin A supplement use. Indeed, these variables may partially capture some of the many channels through which income affects child health and nutrition. Table 5, Row 1 shows that a 10% increase in Per Capita Income is associated with 1.7% (statistically significant at 5% level of significance) increase in the likelihood of consumption of additional food items. When disaggregated with respect to gender, we find that elasticities are 0.235 (statistically significant at 5% level of significance) and 0.149 (not statistically significant at conventional levels) for boys and girls, respectively.

Similarly, we also estimate the relationship between income and individual dietary components like meat, milk products, cereals, eggs, and pulses (Table 5). We find that a 10% increase in Per Capita Income is associated with 8.1% increase in the likelihood of an egg being consumed in the last 24 h. Again, the coefficient of this relationship for boys is almost three times that of the girls. Similarly, coefficients for milk products and cereals are larger for boys, though not statistically significant. We also find that a 10% increase in income is associated with an 11.5% increase in the likelihood of consuming meat in the last 24 h. This increase is fairly equally distributed among boys and girls in our sample.

Table 5 also provides the results for the relationship between Per Capita Income and Vaccines and Vitamin A Supplements. We find that a doubling of per capita income is associated with an increase of 9% in the likelihood of a child given additional vaccine, statistically significant at 10% level of significance. The elasticity for boys, 0.156 (statistically significant at 10% level of significance), is four times greater than that of the girls, which is 0.044 and not statistically significant at conventional levels. Regressions for Vitamin A Supplements do not appear to be significantly related to increase in per capita income. In most cases, Table 5 results show that the gradient for boys is greater than that of girls and is suggestive of inequality in intra-household resource allocation. Furthermore, these results help explain the differences in magnitudes of income-child health relationship among boys and girls in rural Pakistan.

Discussion

In this paper, using Pakistan as a case, we investigated the relationship between income and child health outcomes and if higher income translates into more diversified nutritional intake among children. Due to a son-preference phenomenon in South Asia, we disaggregated these results by gender to understand if gains from increases in income are equally distributed between different members of the household. We find that an increase in per-capita income is associated with an increase in WAZ and WHZ scores but not HAZ scores and the magnitude of income-nutrition gradient among boys is higher. In terms of the diversity of nutritional intake, we find that an increase in income is associated with improved dietary diversity and increased likelihood of consumption of most foods. Again, gains appear to be higher among male children as compared to female children.

Previous research provides mixed evidence for the presence of an income-nutrition gradient, with studies on both sides of the spectrum. Our findings are in line with the literature that suggests that income is related to improved nutritional outcomes among children (Case et al., 2002; Currie & Stabile, 2003; Smith & Haddad, 2002). However, we did not find significant results for the HAZ score. We suspect these results may be due to the cross-sectional nature of our data which does not allow us to study long term changes, which are more characteristic of child stunting (McGovern et al., 2017). Additionally, research in the context of South Asia highlights the presence of a ‘son preference’, where male children are preferred over daughters. Yet, little attention had been given to investigating the presence of son-preference in income-nutrition relationship, especially in the context of Pakistan. Our findings support the existing literature on son-preference (Abdullah & Wheeler, 1985; Brown et al., 1982; Carloni, 1981; Chen et al., 1981; Javed & Mughal, 2019; Jayachandran & Pande, 2017) and add to it by examining the sex disparities in income-nutrition relationships for Pakistan. This finding with respect to sex disparities in the income-nutrition relationship is unique, as little work has been done to document the gendered differences in income-nutrition gradient, especially in Pakistan.

There are several implications of our findings. First, an emphasis on effective nutritional programming can help in improving health outcomes. Nutritional programming focuses on the relationship between critical windows in the development of early life and the nutritional environment at that time. Specifically, undernourishment in the womb can be linked to severe developmental challenges later in life. The fetus makes adjustments based on the predicted environment available after birth, and the prenatal nutritional environment is the main source of information for making these predictions (“Nutritional programming during pregnancy and in early life”, 2011). Work in Gambia finds that for populations with high rates of under-nutrition in early life, there is greater susceptibility to infection related mortality and morbidity later in life (Moore, 2017). According to the National Nutrition Survey (NNS) 2018 for Pakistan (Government of Pakistan & UNICEF, 2019), women of reproductive age in Pakistan have severe nutritional deficiencies. Approximately 14.4% were underweight and 13.8% were obese. The prevalence of anemia very high (41.7%) and Vitamin A deficiency estimated around 22.4%. (UNICEF, 2022) For Pakistan, nutritional programming with an emphasis on gender can go a long way. Our findings also point towards a gender bias in income-health relationship, as well as consumption of health inputs like dietary diversity, suggesting a need to incorporate gender in nutritional programming. In recent years, there have been a number of interventions in Pakistan to improve child anthropometrics. Some of these have included school health programs which focus on providing nutrition to school going children (Niazi et al., 2012), micronutrient initiatives to address deficiencies such as iron, iodine, vitamin A, and zinc, among other micronutrients (Nutrition International, 2020), and a national nutrition program which targets various aspects of nutrition as well as maternal and child, infant, adolescent and adult nutrition (Ministry of National Health Services Regulation and Coordination, 2020). A specific focus on gender in nutrition is reflected in the Tawana Pakistan Project (Badruddin et al., 2008). This focused on increasing primary school enrollment among girls in villages, and also on combating malnutrition by providing them with freshly prepared meals is a step in the right direction. The program saw a reduction in malnutrition, stunting, and wasting in the girls in the target schools. It also saw an increase in the attendance of girls. Similarly, in other countries and municipalities such as Bangladesh and Philadelphia, nutrition interventions that have focused specifically on incorporating a gender dimension have been successful in mitigating some of the bias towards female children (Lannotti et al., 2009; Núñez et al., 2015).

While interventions targeted towards female children in the household can have positive impacts in the short to medium term, societal change will be required in the longer term to prevent discrimination against women in all forms, including nutrition deprivation (Haddad & Zeller, 1996). Such a shift involving female empowerment and expanded control of resources by women can enable greater investments in child health (Allendorf, 2007; Handa, 1996).

Second, we find evidence for an income-nutrition gradient for both WAZ and WHZ scores, suggesting that higher income, in our sample, translates into better health outcomes. Our findings with respect to income and WAZ and WHZ scores raise questions around how poverty alleviating interventions should be designed. In recent years, there has been an increase in cash transfers to households to improve child health outcomes. However, there is mixed evidence on their success in alleviating poverty and improving nutrition outcomes globally (Barham & Maluccio, 2009; Baulch, 2010; Gertler, 2004) and in Pakistan (Fenn et al., 2017; Jahangeer et al., 2020; Nayab & Farooq, 2014). For instance a recent study in Pakistan found that cash transfers did not lead to an improvement in anthropometrics (Jahangeer et al., 2020). However, another study found that they led to positive impact on health outcomes (Nayab & Farooq, 2014). More recent studies suggest that cash transfers coupled with behavioral interventions can lead to more promising results as they not only target income increase but also increase consumption of health inputs (Ahmed et al., 2019).

In our study, we investigated the relationship between income and dietary diversity, intake of micronutrients such as Vitamin A, and adoption of childhood immunization as potential health inputs, which may explain the positive income-child health gradient. We found that increase in income was associated with greater food diversity score, and higher likelihood of egg and meat consumption for the children. This result is consistent with previous studies indicating a positive relationship between income and dietary diversity and other health inputs (Annim & Frempong, 2018; Singh et al., 2020), which in turn result in better child health outcomes. However, gains in the consumption of these health inputs due to increase in income are higher for male children as compared to female children. This suggests that behavioral interventions which educate households on the benefits of a more equitable intrahousehold allocation, diversified diet and other health behaviors, such as seeking medical care, alongside cash transfers can help in creating an environment which may lead to better health outcomes (Adato & Bassett, 2009; Ahmed et al., 2019; Manley et al., 2013). Such interventions can be built into programs such as the EHSAAS welfare program in Pakistan which target the bottom 20% with cash transfers to raise per-capita incomes (Poverty Alleviation and Social Safety Division, 2020).

While targeted programs can have beneficial outcomes in the short to medium term, over the longer term, a greater commitment by the government for more broad based social welfare programs can enable greater and more equitable redistribution of resources (Korpi & Palme, 1998).

Conclusion

Using Pakistan as a case, we estimated the relationship between income and child health outcomes and if higher income translates into more diversified nutritional intake among male and female children. We found that an increase in per-capita income is associated with an increase in WAZ and WHZ scores but not HAZ scores and the magnitude of income-nutrition gradient among boys was higher. In terms of the diversity of nutritional intake, we find that an increase in income is associated with improved dietary diversity and increased consumption of most food items. Again, gains appear to be higher among male children. Our findings point towards a need to design gender-sensitive health interventions and raise important avenues for discussion with regards to designing poverty alleviating interventions.

Notes

While the survey also includes questions on vegetable and fruit intake of children, there is a lot of missing information in those variables and therefore we decided to not use those questions.

Table A1 provides robustness checks with fewer controls. Our estimates remain stable and robust and we observe that gains from increase in income are greater for boys as compared to girls. Table A2 provides similar regressions with income coded in quartiles. Again, the gains seem to be larger for boys as compared to girls for both WAZ and WHZ outcomes. Furthermore, the gains seem to increase with the increase in income-levels.

References

Abdullah, M., & Wheeler, E. F. (1985). Seasonal variations, and the intra-household distribution of food in a Bangladeshi village. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 41(6), 1305–1313.

Adams, P., Hurd, M. D., McFadden, D., Merrill, A., & Ribeiro, T. (2003). Healthy, wealthy, and wise? Tests for direct causal paths between health and socioeconomic status. Journal of Econometrics, 112(1), 3–56.

Adato, M., & Bassett, L. (2009). Social protection to support vulnerable children and families: The potential of cash transfers to protect education, health and nutrition. AIDS Care, 21(sup1), 60–75.

Agrawal, S., Kim, R., Gausman, J., Sharma, S., Sankar, R., Joe, W., & Subramanian, S. V. (2019). Socio-economic patterning of food consumption and dietary diversity among Indian children: Evidence from NFHS-4. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 73(10), 1361–1372.

Ahmed, A., Hoddinott, J., & Roy, S. (2019). Food transfers, cash transfers, behavior change communication and child nutrition: Evidence from Bangladesh. International Food Policy Research Institute.

Allendorf, K. (2007). Do women’s land rights promote empowerment and child health in Nepal? World Development, 35(11), 1975–1988.

Annim, S. K., & Frempong, R. B. (2018). Effects of access to credit and income on dietary diversity in Ghana. Food Security, 10, 1649–1663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0862-8

Badruddin, S. H., Agha, A., Peermohamed, H., Rafique, G., Khan, K. S., & Pappas, G. (2008). Tawana project-school nutrition program in Pakistan-its success, bottlenecks and lessons learned. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 17(S1), 357–360.

Barham, T., & Maluccio, J. A. (2009). Eradicating diseases: The effect of conditional cash transfers on vaccination coverage in rural Nicaragua. Journal of Health Economics, 28(3), 611–621.

Baulch, B. (2010). The medium-term impact of the primary education stipend in rural Bangladesh. International Food Policy Research Institute.

Behrman, J. R. (1988a). Nutrition, health, birth order and seasonality: Intrahousehold allocation among children in rural India. Journal of Development Economics, 28(1), 43–62.

Behrman, J. R. (1988b). Intrahousehold allocation of nutrients in rural India: Are boys favored? Do Parents exhibit inequality aversion? Oxford Economic Papers, 40(1), 32–54.

Behrman, J. R., & Deolalikar, A. B. (1987). Will developing country nutrition improve with income? A case study for rural South India. Journal of Political Economy, 95(3), 492–507.

Black, R. E., Allen, L. H., Qar, Z., Bhutta, A., Caulfield, L. E., de Onis, M., Ezzati, M., Mathers, C., Rivera, J., the Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. (2008). Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet, 371(9608), 243–260.

Brown, C., Ravallion, M., & van de Walle, D. (2019). Most of Africa’s nutritionally deprived women and children are not found in poor households. Review of Economics and Statistics, 101(4), 631–644.

Brown, K. H., Black, R. E., Becker, S., Nahar, S., & Sawyer, J. (1982). Consumption of foods and nutrients by weanlings in rural Bangladesh. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 36(5), 878–889.

Burgess, S. M., Propper, C., & Rigg, J. (2004). The impact of low-income on child health: Evidence from a birth cohort study. London School of Economics.

Carloni, A. S. (1981). Sex disparities in the distribution of food within rural households. Food and Nutrition, 7(1), 3–12.

Case, A., Lubotsky, D., & Paxson, C. (2002). Economic status and health in childhood: The origins of the gradient. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1308–1334.

Cheema, A., Khan, S., Liaqat, A., & Mohmand, S. K. (2022). Canvassing the gatekeepers: A field experiment to increase women voters’ turnout in Pakistan. American Political Science Review, 2022, 1–21.

Chen, L. C., Huq, E., & d’Souza, S. (1981). Sex bias in the family allocation of food and health care in rural Bangladesh. Population and Development Review, 7(1), 55–70.

Cornia, G., & Stewart, F. (1992). Two errors of targeting. Washington: World Bank Conference on Public Expenditures and the Poor: Incidence and Targeting.

Cowan, B., & Dhanoa, J. (1983). The prevention of toddler malnutrition by home-based nutrition health education. Nutrition in the community: A critical look at nutrition policy, planning, and programs. Wiley.

Currie, A., Shields, M. A., & Price, S. W. (2007). The child health/family income gradient: Evidence from England. Journal of Health Economics, 26(2), 213–232.

Currie, J., & Stabile, M. (2003). Socioeconomic status and child health: Why is the relationship stronger for older children? American Economic Review, 93(5), 1813–1823.

Fenn, B., Colbourn, T., Dolan, C., Pietzsch, S., Sangrasi, M., & Shoham, J. (2017). Impact evaluation of different cash-based intervention modalities on child and maternal nutritional status in Sindh Province, Pakistan, at 6 mo and at 1 y: A cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Medicine, 14(5), e1002305.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2005). The causal effect of income on health: Evidence from German reunification. Journal of Health Economics, 24(5), 997–1017.

Gertler, P. (2004). Do conditional cash transfers improve child health? Evidence from PROGRESA’s control randomized experiment. American Economic Review, 94(2), 336–341.

Government of Pakistan & UNICEF. (2019). National Nutrition Survey 2018: Key findings report. Islamabad: Nutrition Wing, Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination, Government of Pakistan.

Gupta, S. D. (2016). Son preference and gender gaps in child nutrition: Does the level of female autonomy matter? Review of Development Economics, 20(2), 375–386.

Haddad, L., & Zeller, M. (1996). How can safety nets do more with less? General issues with some evidence from Southern Africa. International Food Policy Research Institute.

Handa, S. (1996). Expenditure behavior and children’s welfare: An analysis of female headed households in Jamaica. Journal of Development Economics, 50(1), 165–187.

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); and Innovative Development Solutions (IDS). (2017). Pakistan Rural Household Panel Survey (PRHPS) 2014, Round 3. Washington, DC: IFPRI [dataset] https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JWMCXY

Jahangeer, A., Zaidi, S., Das, J., & Habib, S. (2020). Do recipients of cash transfer scheme make the right decisions on household food expenditure? A study from a rural district in Pakistan. JPMA, 70(5), 796–802.

Javed, R., & Mughal, M. (2019). Have a son, gain a voice: Son preference and female participation in household decision making. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(12), 2526–2548.

Jayachandran, S., & Pande, R. (2017). Why are Indian children so short? The role of birth order and son preference. American Economic Review, 107(9), 2600–2629.

Korpi, W., & Palme, J. (1998). The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: Welfare state institutions, inequality, and poverty in the Western countries. American Sociological Review, 63, 661–687.

Lannotti, L., Cunningham, K., & Ruel, M. (2009). Improving diet quality and micronutrient nutrition. International Food Policy Research Institute.

Mahmudiono, T., Sumarmi, S., & Rosenkranz, R. R. (2017). Household dietary diversity and child stunting in East Java, Indonesia. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 26(2), 317–325.

Manley, J., Gitter, S., & Slavchevska, V. (2013). How effective are cash transfers at improving nutritional status? World Development, 48, 133–155.

Marcoux, A. (2002). Sex differentials in undernutrition: A look at survey evidence. Population and Development Review, 28(2), 275–284.

McGovern, M. E., Krishna, A., Aguayo, V. M., & Subramanian, S. V. (2017). A review of the evidence linking child stunting to economic outcomes. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(4), 1171–1191.

Meer, J., Miller, D. L., & Rosen, H. S. (2003). Exploring the health–wealth nexus. Journal of Health Economics, 22(5), 713–730.

Melaku, Y. A., Gill, T. K., Taylor, A. W., Adams, R., Shi, Z., & Worku, A. (2018). Associations of childhood, maternal and household dietary patterns with childhood stunting in Ethiopia: Proposing an alternative and plausible dietary analysis method to dietary diversity scores. Nutrition Journal, 17(1), 14.

Miller, B. D. (1997). Social class, gender and intrahousehold food allocations to children in South Asia. Social Science & Medicine, 44(11), 1685–1695.

Ministry of National Health Services Regulation and Coordination. (2020). Nutrition wing: Pakistan. Retrieved July 21, 2020 from http://nwpk.org/projects.html.

Moges, T., Birks, K. A., Samuel, A., Kebede, A., Kebede, A., Wuehler, S., Zerfu, D., Abera, A., Mengistu, G., & Tesfaye, B. (2015). Diet diversity is negatively associated with stunting among Ethiopian Children 6–35 months of age. European Journal of Nutrition & Food Safety, 5(5), 1185–1186.

Moore, S. E. (2017). Early-life nutritional programming of health and disease in the Gambia. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism, 70(3), 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1159/000456555

Nayab, D., & Farooq, S. (2014). Effectiveness of cash transfer programmes for household welfare in Pakistan: The case of the Benazir income support programme. The Pakistan Development Review, 53(2), 145–174.

Niazi, A. K., Niazi, S. K., & Baber, A. (2012). Nutritional programmes in Pakistan: A review. Journal of Medical Nutrition and Nutraceuticals, 1(2), 98–100.

Nnyepi, M. S. (2007). Household factors are strong indicators of children’s nutritional status in children with access to primary health care in the greater Gaborone area. Scientific Research and Essay, 2(2), 55–61.

Núñez, A., Robertson-James, C., Reels, S., Jeter, J., Rivera, H., & Yusuf, Z. (2015). Exploring the role of gender norms in nutrition and sexual health promotion in a piloted school-based intervention: The Philadelphia Ujima™ experience. Evaluation and Program Planning, 51, 70–77.

Nutrition International. (2020). Micronutrient Initiative: Pakistan. Retrieved July 21, 2020 from http://www.micronutrient.org/english/view.asp?x=606

Nutritional programming during pregnancy and in early life. (2011). Nutri-facts. Retrieved February 23, 2023 from https://www.nutri-facts.org/en_US/news/articles/nutritional-programming-during-pregnancy-and-in-early-life.html

Pena, M., & Bacallao, J. (2002). Malnutrition and poverty. Annual Review of Nutrition, 22(1), 241–253.

Poverty Alleviation and Social Safety Divison. (2020). Ehsaas Welfare Program: Pakistan. Retrieved July 21, 2020 from https://www.pass.gov.pk/

Rah, J. H., Akhter, N., Semba, R. D., De Pee, S., Bloem, M. W., Campbell, A. A., MoenchPfanner, R., Sun, K., Badham, J., & Kraemer, K. (2010). Low dietary diversity is a predictor of child stunting in rural Bangladesh. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 64(12), 1393–1398.

Singh, S., Jones, A. D., DeFries, R. S., & Jain, M. (2020). The association between crop and income diversity and farmer intra-household dietary diversity in India. Food Security, 12, 1–22.

Smith, L. C., & Haddad, L. (2002). How potent is economic growth in reducing undernutrition? What are the pathways of impact? New cross-country evidence. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 51(1), 55–76.

UNICEF. (2019). Data by topic and country: Child nutrition. Retrieved June 19, 2020 from https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/child-nutrition/

UNICEF. (2022). Maternal Nutrition Strategy 2022–2027 Pakistan. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/pakistan/media/4356/file/Pakistan%20Maternal%20Nutrition%20Strategy%202022-27.pdf

Vella, V., Tomkins, A., Borgesi, G. B., & Dryem, V. Y. (1994). Determinants of stunting and recovery from stunting in Northwest Uganda. International Journal of Epidemiology, 23(4), 782–786.

West, P. (1997). Health inequalities in the early years: Is there equalisation in youth? Social Science & Medicine, 44(6), 833–858.

WHO. (2006). WHO child growth standards: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. World Health Organization.

WHO. (2020). Nutrition: Stunting in a Nutshell. Retrieved June 19, 2020 from https://www.who.int/nutrition/healthygrowthproj_stunted_videos/en/

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, H., Khalid, H. Income-Nutrition Gradient and Intrahousehold Allocation in Rural Pakistan. Matern Child Health J 27, 1208–1218 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03633-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03633-4