Abstract

Objective: To summarize changes in folic acid awareness, knowledge, and behavior among women of childbearing age in the United States since the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) 1992 folic acid recommendation and later fortification. Methods: Random-digit dialed telephone surveys were conducted of approximately 2000 women (per survey year) aged 18–45 years from 1995–2005 in the United States. Results: The percentage of women reporting having heard or read about folic acid steadily increased from 52% in 1995 to 84% in 2005. Of all women surveyed in 2005, 19% knew folic acid prevented birth defects, an increase from 4% in 1995. The proportion of women who reported learning about folic acid from health care providers increased from 13% in 1995 to 26% in 2005. The proportion of all women who reported taking a vitamin supplement containing folic acid increased slightly from 28% in 1995 to 33% in 2005. Among women who were not pregnant at the time of the survey in 2005, 31% reported taking a vitamin containing folic acid daily compared with 25% in 1995. Conclusions: The percentage of women taking folic acid daily has increased modestly since 1995. Despite this increase, the data show that the majority of women of childbearing age still do not take a vitamin containing folic acid daily. Health care providers and maternal child health professionals must continue to promote preconceptional health among all women of childbearing age, and encourage them to take a vitamin containing folic acid daily.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Spina bifida and anencephaly – the most common neural tube defects (NTDs) – are serious birth defects that occur early in pregnancy, often before a woman realizes she is pregnant. Important studies show that intake of the B vitamin folic acid reduces the incidence of NTDs by 50–70% when taken before conception and during the first trimester of pregnancy [1, 2]. This compelling research prompted the 1992 U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) recommendation that all women of childbearing age who are capable of becoming pregnant consume 400 micrograms (mcg) of folic acid daily [3]. For women who previously had an infant with an NTD and were planning a pregnancy, it was recommended that they consume a much larger dose, 4,000 mcg of folic acid per day at least one month before becoming pregnant and during the first three months of pregnancy [3].

In 1998, the 1992 USPHS recommendation was reaffirmed by the Institute of Medicine, which stated that women capable of becoming pregnant should take 400 micrograms of “synthetic folic acid” daily from fortified foods or supplements or a combination of the two, in addition to consuming natural folate from a varied diet [4]. Additionally, in 1998 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began requiring folic acid fortification of enriched breads, cereals, flours, pastas, rice, and other grain products [5], to aid in increasing folic acid consumption by an estimated average of 100 mcg daily in women of childbearing age. Other organizations, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have supported the USPHS recommendation [6, 7]. National and state organizations implemented educational and media campaigns during the mid-1990s to promote the awareness and consumption of folic acid among women of childbearing age [8, 9]. Since the implementation of national policies, the number of pregnancies affected by NTDs in the U.S has decreased approximately 26% – from 4,000 affected pregnancies prior to fortification to 3,000 affected pregnancies after fortification [10]. Despite these efforts, the 50 percent reduction anticipated by the USPHS in 1992 has not been forthcoming. This report summarizes results from nine surveys conducted between 1995–2005 after the USPHS 1992 recommendation and folic acid fortification. It documents the steady increase in awareness and knowledge of folic acid – and the as yet modest change in consumption of a vitamin containing folic acid – among U.S. women of childbearing age.[11].

Methods

The data for this study include a national sample of approximately 2000 women (per survey year) aged 18–45 years from 1995–2005. The March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation contracted the Gallup Organization to conduct random-digit-dialed telephone surveys. Since 1995, response rates have ranged from 24% to 52%. The response rate for the 2005 survey was 32% (2,647 women). Statistical estimates were weighted based on Current Population Survey (CPS) data to reflect the total population of women aged 18–45 years in the contiguous United States who resided in households with telephones. In 2005, the sampling design included an oversampling of women ages 18–25. In 1995–2004, the margin of error for estimates based on the total sample size was ±3% and in 2005 it was ±2% . The questionnaire and methods used were described previously and were the same in all survey years [12].

Results

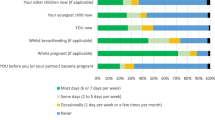

Table 1 displays the percentage of women reporting awareness of and knowledge about folic acid, and their daily use of vitamins containing folic acid. Between 1995 and 2001, the percentage of women reporting having heard or read about folic acid increased from 52% in 1995 to 79% in 2001. Since 2001, awareness of folic acid has remained relatively constant at about 80%. Of all women surveyed in 2005, 19% knew that folic acid prevented birth defects, compared to 4% in 1995. Also in 2005, 7% of women knew that folic acid should be taken before pregnancy, compared to 2% in 1995. The proportion of all surveyed women who reported taking a vitamin supplement containing folic acid daily has remained almost unchanged but increased gradually from 28% in 1995 to 40% in 2004, but decreased to 33% in 2005. Of women surveyed in 2005 who were aware of folic acid, 26% identified green leafy vegetables as good sources of folic acid. However, in 2000, fortified cereals were added to the list of possible sources, and only 2–5% of women identified fortified cereals as a good source of folic acid.

Table 1 also displays women's reported sources of information about folic acid. From 1995 to 2005, the proportion of women who reported learning about folic acid from health care providers showed a two-fold increase from 13% in 1995 to 26% in 2005. Of women surveyed in 2005, 31% reported that their health care provider discussed the benefits of folic acid with them, compared to 24% in 2001. Of the same group of women in 2005, 30% reported being told by their health care provider that folic acid prevented birth defects. However, only 7% of women in 2005 reported that their health care provider said folic acid needs to be taken before pregnancy. This statistic has ranged from 3% in 2004 to 8% in 2003 since its inclusion in the survey in 2002.

For the last ten years, the percentage of women learning about folic acid from media sources such as radio and television increased from 10% in 1995 to 18% in 2005, whereas information about folic acid obtained from magazines or newspapers decreased from 35% in 1995 to 26% in 2005. These results are shown in Table 1.

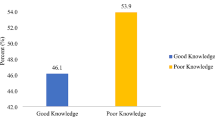

Table 2 displays the percentage of women of childbearing age 18–45 who reported awareness of folic acid by selected sociodemographic characteristics. In 2005 the women least likely to be aware of folic acid were non-white women (71%), women aged 18–24 years (72%), those women with less than a high school education (58%), and those with a household income of less than $25,000 (72%). These results are consistent with years prior to 2005.

Table 3 displays the percentage of women of childbearing age 18–45 who reported taking folic acid daily, by selected sociodemographic characteristics. Of all women surveyed in 2005, those least likely to consume a vitamin containing folic acid daily include non-white women (23%), those women aged 18–24 (24%), those with less than a high school education (20%), and those with household incomes of $25,000 or less (27%). Among women who were not pregnant at the time of the survey in 2005, 31% reported taking a vitamin containing folic acid daily compared with 25% in 1995. Among women who were surveyed in 2005 who were currently pregnant, 90% reported taking a vitamin containing folic acid daily compared to 79% in 1997.

In 2005, 67% of childbearing age women reported they did not take daily supplements. The most common reasons for not taking any daily vitamin or mineral supplements are that they “forget to take them”, stated by 28% of women, or “don't feel they need them” as reported by 16% of women. However, in 2005, 86% of women who were not currently taking daily vitamins or mineral supplements reported they would be likely to start taking a multivitamin daily if advised by their health care provider or physician.

Discussion

The findings in this study show that whereas a large percentage of women have heard of folic acid, only a small proportion are aware that folic acid prevents birth defects and should be taken before pregnancy. Furthermore, despite the USPHS recommendation in 1992 [3] the percentage of women taking a vitamin supplement containing folic acid daily has only modestly increased between 1995 and 2005. There was a substantive increase in the percentage of women taking folic acid daily in 2004, but this increase was not sustained in 2005. Clearly, the observed increases in awareness and knowledge about folic acid are not translating into increased multivitamin use.

Increased awareness of the importance of folic acid is due in part to educational outreach activities undertaken over the years by CDC, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation and its chapters, the Spina Bifida Association of America, and members of the National Council on Folic Acid. These activities culminated in a national meeting in January 1999 to coordinate a folic acid promotional campaign (May through September 1999) with continuing independent educational outreach efforts [8]. Although there were no substantial changes in folic acid use, recent dietary habits might provide insight into the sudden increase in folic acid use in 2004. A recent study found that women on low-carbohydrate diets were 50% more likely to take folic acid daily than women on other diets; however, in 2005, folic acid use was similar across dieting types [13]. The results from the 2004 survey may be an anomalous finding, given that many of the findings returned to pre-2004 levels (e.g., multivitamin use). Our findings may suggest the need for more continued and increased media messages to encourage women to consume adequate amounts of folic acid every day through fortified foods, dietary supplements, and a folate-rich diet. Furthermore, communities should identify food products that provide recommended levels of folic acid available in local grocery stores, and encourage women to select diets with sufficient folic acid.

Recent educational efforts alone do not appear to be adequate to demonstrate an impact on changing behavior with regard to folic acid consumption. The findings from this report can be used to develop multi-pronged targeted public health programs to increase the number of women of childbearing age consuming a vitamin containing folic acid daily. Demographic, sociocultural, and environmental factors impact behavior and more attention must be given to these factors. Results from these surveys indicate that variations exist in folic acid awareness, knowledge, and use among women of different race/ethnicity, age groups, education levels, and socioeconomic status. This suggests that the linkage between folic acid awareness, knowledge, and use is more complicated than simply increasing awareness and knowledge. Non-white women, those between the ages of 18–24, those less educated, and those of a lower socioeconomic status are associated with both lower folic acid knowledge and lower use of a vitamin containing folic acid. Targeted messages and teachable opportunities of communication for younger women, women of racial and ethnic groups, and women of low socioeconomic status need to be identified and mobilized to increase the number of childbearing age women taking folic acid daily, regardless of pregnancy plans.

Our results indicated that despite the fact that some women learn about folic acid from their health care provider, most women are not currently following their health care provider's advice even though they might feel the recommendation is important. This is apparent when looking at the proportion of women taking a multivitamin daily. In addition, women report they do not take a vitamin containing folic acid because they “feel they don't need to”, or are not receiving the folic acid message from their health provider. More research is needed to understand what the motivators and barriers are for consuming a multivitamin containing folic acid daily to design appropriate interventions (whether service delivery, policy, media messages, or educational in nature) for women of childbearing age. It is important to continue to target educational efforts at health care providers with emphasis on the importance of women of childbearing age taking folic acid daily to prevent NTDs. But, education of health care providers may not be enough by itself. Changing health care provider practices is not merely a matter of knowledge acquisition. Public health programs need to forge stronger alliances with the health care delivery systems at the local and national level to develop and incorporate meaningful folic acid messages into routine counseling and existing health programs and services, since preconceptional counseling is not available to all women of childbearing age. Strategies are needed to understand the context of patient and provider interaction to promote consumption of a daily vitamin containing folic acid among all women of childbearing age, regardless of whether or not they are planning a pregnancy.

The findings from this survey are subject to several important limitations. First, because women under the age of 18 were not included in the survey, the full extent of folic acid knowledge and consumption among the entire population of women of childbearing age is unknown. Second, women without telephones were excluded; therefore, data may underestimate the number of women of childbearing age from low socioeconomic groups. Third, folic acid knowledge and consumption of nonparticipants might have been different from those of participants: participating women were more highly educated than the total U.S. population. The prevalence of consuming vitamin supplements might have been higher among these women than among U.S. women in general because vitamin consumption is positively correlated with education [11, 12]. Fourthly, folic acid use may have been under ascertained since we did not have information on women's dietary folate consumption or their folate levels. Further, self-report of dietary intake, such as taking multivitamins, could be biased by social desirability – the tendency of respondents to respond in a way so as to avoid disapproval, rather than reporting actual beliefs or actions. Finally, surveys of a more representative sample of women of childbearing age in the United States are needed to obtain more precise estimates of folic acid use among this population.

Policy and practice implications

Fortification efforts are an effective method of reducing the number of NTD-affected pregnancies, and have led to a 26% decline in the number of NTD-affected pregnancies since the 1998 mandate that enriched cereal grain flours be fortified with 140 mcg per 100 gram (g) [10]. Although this is a substantial decline, it does not reach the 50% reduction estimated by the USPHS in 1992 [1]. While the U.S. is seeing a decline in the number of NTDs, other countries have seen similar or greater declines. In Chile for example, wheat flour was fortified in 2000 with 220 mcg folic acid per gram of the pre-mix already used in wheat flour. Nine public hospitals in Santiago, Chile, which account for approximately 25% of the births in that country, reported a 40% decline in the number of NTDs [14]. Canada's flour was fortified with folic acid in 1998 with 150 mcg of folic acid per 100 g of grain and certain provinces reported almost a 50% decline of NTDs[15].

Some countries have chosen to recommend the use of folic acid supplementation for women of childbearing age instead of fortification. One study examined data from thirteen birth defect registries from areas in Europe and Israel with over 8,000 cases of spina bifida and anencephaly to determine the impact of recommendations on the rate of NTDs [16]. Although some countries saw a slight decline in rates, the majority of countries saw no detectable decrease in the rates of NTDs using recommendations for supplementation alone [16]. This small decline implies that although recommendations might be an important aspect of reducing the rate of NTDs, programs such as fortification could have a broader and more effective impact on the overall rates of NTDs. Countries who try to use a combination of methods – such as fortification and supplementation, along with recommendations and education programs – might see a greater decline in the rates of NTDs.

Conclusions

The Healthy People 2010 objectives call for an increase to 80% in the number of nonpregnant women aged 15–44 years consuming daily amounts of 400 mcg of folic acid through fortified foods or dietary supplements (Objective 16–16a) and to increase the median red blood cell (RBC) folate level to 220 ng/ml among nonpregnant women aged 15 to 44 years by 2010 (Objective 16–16b) [17]. Although substantial increases in RBC folate levels among women of childbearing age has been achieved [18], more aggressive efforts are needed to increase the number of women consuming 400 mcg of folic acid daily through fortified food or dietary supplement to reduce the prevalence of NTDs.

To succeed in eliminating all folic acid preventable birth defects beyond what fortification has already achieved, more must be done besides educating women and their health care providers. Pregnancies and births affected by spina bifida or anencephaly have profound physical, emotional, and financial effects on families and communities. This year there will be an estimated 3,000 NTD-affected pregnancies. This study reinforces the need for public health practitioners to mobilize multiple sectors, including health care professionals, government organizations, state and local organizations, advocacy groups, and concerned citizens to coordinate efforts and activities to help alleviate a devastating public health issue.

References

MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. Lancet 1991;338:131–7.

Milunsky A, Jick H, Jick SS, et al. Multivitamin/folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy reduces the prevalence of neural tube defects. JAMA 1989;262:2847–52.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendation for the use of folic acid to reduce the number of cases of spina bifida and other neural tube defects. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1992;41(14):1–7.

Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998.

Food and Drug Administration. Food standards: amendment of standards of identity for enriched grain products to require addition of folic acid. Fed Regist 1996;61:8781–97.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Genetics. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects. Pediatrics 1999;104:325–7.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Planning your pregnancy and birth. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2000.

Daniel K, Prue C. Tracking the process and progress of the national folic acid campaign. In: Steckler A, Linnan L, editors. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention program for reducing risk for neural tube defects—South Carolina, 1992–1994. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep 1995;44:141–2.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Spina bifida and anencephaly before and after folic acid mandate—United States, 1995–1996 and 1999–2000. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep 2004;53:362–5.

March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation. Folic acid and the prevention of birth defects: A national survey of pre-pregnancy awareness and behavior among women of childbearing age 1995–2005. White Plains, NY.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Knowledge and use of folic acid by women of childbearing age – United States, 1995. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1995;44:716–8.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Folate status in women of childbearing age- United States, 1999. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2000;49:962–4

Hertrampf E, Cortes F. Folic acid fortification of wheat flour: Chile. Nutr Rev 2004;62:S44–8.

Mills J, Signore C. Neural tube defect rates before and after food fortification with folic acid. Birth Defects Research (Part A). Clin Mol Teratol 2004;70:844–5.

Botto LD, Lisi A, Robert-Gnansia E,xd et al. International retrospective cohort study of neural tube defects in relation to folic acid recommendations: are the recommendations working? BMJ 2005;330:571–6.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of dietary supplements containing folic acid among childbearing age women—United States 2004–2005. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54:955–8.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010 (conference ed, 2 vols). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000.

Acknowledgements

Trends in Folic Acid Awareness and Behavior in the United States: The Gallup Organization for the March of Dimes Foundation Surveys, 1995–2005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Green-Raleigh, K., Carter, H., Mulinare, J. et al. Trends in Folic Acid Awareness and Behavior in the United States: The Gallup Organization for the March of Dimes Foundation Surveys, 1995–2005. Matern Child Health J 10 (Suppl 1), 177–182 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-006-0104-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-006-0104-0