Abstract

Recent work on mood choice considers fine-grained semantic differences among desire predicates (notably, ‘want’ and ‘hope’) and their consequences for the distribution of indicative and subjunctive complement clauses. In that vein, this paper takes a close look at ‘intend’. I show that cross-linguistically, ‘intend’ accepts nonfinite and subjunctive complements and rejects indicative complements. This fact poses difficulties for recent approaches to mood choice. Toward a solution, a broad aim of this paper is to argue that—while ‘intend’ is loosely in the family of desire predicates—it differs from ‘want’ and ‘hope’ in that it has a causative component, and this is relevant to its mood choice behavior, given that causative predicates also systematically reject indicative complements. More concretely, my analysis has three ingredients: (i) following related proposals in philosophy, intention reports have causally self-referential content; (ii) encoding causal self-reference requires abstraction over the complement clause’s eventuality argument; and (iii) nonfinite and subjunctive clauses enable such abstraction but indicative clauses do not. Aside from causative predicates, independent support for the proposal comes from the syntax of belief-/intention-hybrid attitude predicates like ‘decide’ and ‘convince’, anankastic conditional antecedents, aspectual predicates, and memory and perception reports. Synthesizing this result with that of previous literature, the emergent generalization is that subjunctive mood occurs in attitude reports that involve either comparison or eventuality abstraction. Toward a unified theory of mood choice, I suggest that both comparison and eventuality abstraction represent departures from the clausal semantics of unembedded assertions and consequently that subjunctive mood signals such a departure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Here and throughout, I use single quotes around a predicate to refer collectively to it and its cross-linguistic translational equivalents.

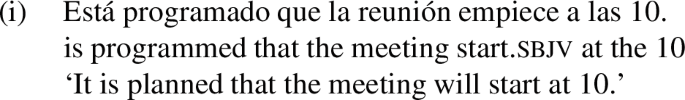

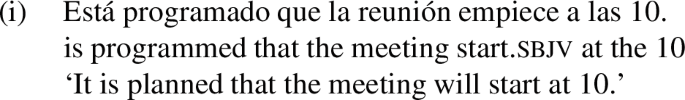

See Nematollahi 2023 for a study that comes to a similar conclusion regarding mood choice in Persian. Nematollahi argues that Persian complement clauses come in two semantic types: \(\langle st\rangle \) (propositions/world descriptions) and type \(\langle \epsilon t\rangle \) (event descriptions), with complements to causative predicates being a canonical example of the latter. For Nematollahi, mood choice in Persian is sensitive to a number of factors, one of which is that subjunctive always appears under predicates that select type \(\langle \epsilon t\rangle \) complements.

Glossing in this paper is kept to a minimum (for example, I do not gloss subject agreement inflectional information on verbs), except when it comes to mood choice in embedded clauses, where the following abbreviations are employed: fut = future; ind = indicative; inf = infinitive; sbjv = subjunctive.

According to Portner and Rubinstein (2020), some Italian speakers do accept indicative complements under volere ‘want’ under some conditions, with a difference in meaning that is not yet clear. I will set this aside in what follows.

Here and throughout, judgments for all unattributed non-English data come from my language consultants, who are named in the Acknowledgements.

According to Villalta (2008), Spanish esperar can take the indicative when the complement clause is about a future event, but in that case it means ‘anticipate’ or ‘expect’ rather than ‘hope’.

For some French speakers, espérer accepts subjunctive complements, at least under some conditions. (See Godard 2012; Anand and Hacquard 2013; Portner and Rubinstein 2020 for relevant discussion.) In that sense, French displays—in some limited form—the same kind of language-internal variability that we’re about to see in Portuguese, Italian, Greek, Romanian, and English.

For Jackendoff and Culicover, these kinds of sentences are the result of coercion: the introduction of semantic material (in this case, ‘bring it about that’) not present in the syntax. Grano (2017b), however, argues that an appropriately formulated semantics for ‘intend’ allows for a coercion-free semantics of the sentences in question. In this paper, I remain neutral on this question; however, this paper’s analysis is compatible with a coercion-free approach—see note 28.

In a similar vein, an anonymous reviewer reports that the French verb compter (literally, ‘count’) has among its various senses an ‘intend’ meaning and can take subjunctive complements with that meaning, whereas an indicative complement gives rise to an ‘expect’-like meaning.

The reviewer also reports a similar contrast between hope and have hopes. Paula Menéndez-Benito (pers. comm.) reports that in Spanish, tener esperanzas ‘have hopes’ may allow for inconsistent outcomes whereas tener la esperanza ‘have the hope’ seems not to, which suggests that the singular vs. plural status of the nominal needs to be taken into account.

For Spanish, French, and one of the two Italian patterns, the ‘intend’ column concerns the pattern for what would be more accurately glossed as ‘have (the) intention’. Elsewhere, the patterns summarized here are for verbal forms only, not nominal forms.

Regarding the French example in (37), while one of my French informants finds it completely natural, another reports that it sounds unnatural but would become perfect if fait ‘made’ were replaced with obligé ‘made’/‘forced’ or forcé ‘made’/‘forced’. In any case, this does not affect the main point that the complement clause has an infinitival syntax.

Examples taken from https://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/faire/32701

According to Portner (2018), causative and implicative predicates “typically take subjunctive, but not in Greek” (p. 75). Examples are provided of causative predicates with subjunctive complements in Spanish and Catalan (p. 77); however, no Greek data with causatives is presented, and according to my informant, Greek causatives embed subjunctives only (see also Rouchota 1994 for this claim). It is also well documented that Greek implicative predicates like ‘manage’ take subjunctive complements as well (see, e.g., Giannakidou and Staraki 2013; Giannakidou and Mari 2021).

In an appendix, Portner and Rubinstein (2020) also consider Catalan, Portuguese, Italian, and Romanian.

For Heim (1992), von Fintel (1999), this background is given by what the attitude holder “believes to be the case no matter how he chooses to act” (Heim 1992, p. 199). Portner and Rubinstein (2020), however, follow Giorgi and Pianesi (1997), Rubinstein (2017) in taking a more flexible approach, where the background is given by some subset of the attitude-holder’s beliefs.

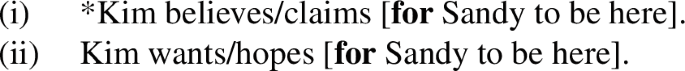

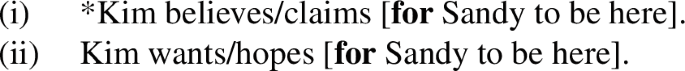

Evidence that for-to infinitives are like subjunctive clauses in being compatible only with verbs that provide a pair of modal backgrounds comes from contrasts like (i)–(ii): verbs that provide just one modal background, like believe and claim, reject for-to complements, whereas verbs that provide a pair of modal backgrounds, like want and hope, accept for-to complements.

Data similar to (51)–(52) are documented by Grano (2017b), building in part on Condoravdi and Lauer 2016. It should be noted, however, that the question of whether one can intend what one believes to be impossible has been the subject of debate among philosophers; see, e.g., Hedman 1970; Ludwig 1992; Buckwalter et al. 2021.

It is also relevant to ask how sentences like (56) behave in other Romance languages. According to Paula Menéndez-Benito (pers. comm.), the Spanish equivalent of (56) requires subjunctive mood:

It turns out that this solution does not cover the full range of data, as Heim herself points out. For example, Heim points out that the account erroneously predicts that ‘I want this weekend to last forever’ presupposes that I believe it is possible for the weekend to last forever. See Grano and Phillips-Brown 2022 for a proposal regarding the semantics of ‘want’ that accommodates this sort of data as well.

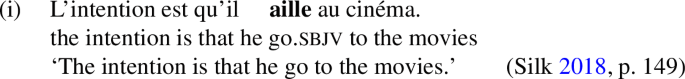

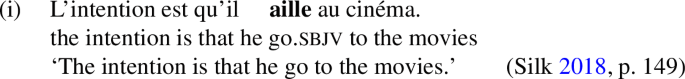

As discussed in Sect. 2.2 above, French avoir l’intention seems not to be comfortable with either indicative or subjunctive mood, though some speakers may accept subjunctive mood under some conditions. Silk cites the following piece of data in support of the conclusion that French ‘intend’ takes subjunctive mood:

However, as a reviewer cautions, there are two complications here. The first is the nominal status of the predicate, as we discussed in Sects. 2.2 and 3.1. The second is that this is a copular construction, which might have its own special properties that would need to be investigated separately.

In fact, Giannakidou and Mari (2021) go so far as to claim that ‘want’ is anti-veridical, so that a wants p entails a believes \(\lnot p\). While I think this is too strong, it is not immediately relevant to this discussion, since the weaker notion of non-veridicality is sufficient on Giannakidou and Mari’s theory to account for the mood choice behavior of ‘want’.

Though see Fara 2013 for potential complications to this simple picture of desire reporting. These complications are orthogonal to the concerns of this paper.

What are ‘worlds compatible with one’s intentions’? Is it something reducible to other concepts related to intention that have emerged in recent literature such as effective preferences (Condoravdi & Lauer, 2016; Grano, 2017b), committed priorities (Rubinstein, 2012), actionable ends (Charlow, 2013), or action goals (Alonso-Ovalle & Menéndez-Benito, 2017)? Possibly so, but this level of articulation will not be relevant to this paper’s core proposal, so I will remain neutral on this question. I will also remain neutral on whether the set of worlds that ‘intend’ quantifies over is derived from a single modal background or from a pair of modal backgrounds that selects a highest-ranked set of worlds, since (unlike for Portner and Rubinstein 2020), this distinction will not play a role in my account of mood choice behavior for this predicate. The only substantive constraint to be imposed on this set of worlds is that it must have a non-empty intersection with the set of worlds compatible with one’s beliefs (see below).

I assume that denotations are relativized to a possible world (w) and an assignment function (g), and beginning with (77), they will also be relativized to a time (t). I represent the assignment function only where it is relevant, namely in (73-c) for the interpretation of PRO. Symbols for primitive semantic types used here and in what follows are: e (individuals), s (possible worlds), t (truth values), i (times), and v (eventualities).

The assumption of individual abstraction in the complement clause still allows for the analysis of non-control intention reports like Kim intends for Sandy to leave, provided we analyze for-to infinitives like for Sandy to leave as involving vacuous individual abstraction. See in this connection Grano 2017a, who follows earlier work by Stephenson (2010) and Pearson (2013) in treating control and non-control clauses as type-theoretically identical.

Here, I use ‘>’ as a relation that holds between two times t and \(t^{\prime }\) iff t is later than \(t^{\prime }\). Note also that the compositional semantics given here embodies the hypothesis that it is the embedding predicate rather than its infinitival complement that encodes future orientation. This is not a new idea (see e.g. Pearson 2016 for a recent example) but also not universally accepted (see e.g. Wurmbrand 2014 for the alternative view). As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, shifting the future orientation to the infinitive would help enable a leaner analysis of attitude verbs (see note 30 below), although for reasons of space I will not pursue this alternative possibility here.

The introduction of the state variable enables but does not compel a more neo-Davidsonian compositional approach to attitude reports, whereby the attitude verb by itself simply denotes a predicate of states, and the complement clause is integrated into the interpretation via a left-peripheral modal functional head, as has been pursued by Kratzer (2006), Moulton (2009), Bogal-Allbritten (2016), Portner and Rubinstein (2020) and others. For now, I will not pursue this approach; however, see Sect. 7 below—where I sketch a way of unifying this paper’s core proposal with Portner and Rubinstein’s (2020) analysis of mood choice—for a few words on what such an approach would look like when applied to intention reports.

The cause* relation plays a role analogous to the resp(onsibility) relation in Grano’s (2017b) approach to the semantics of intention reports. The resp relation is originally due to Farkas (1992), for whom it is a relation between individuals and situations. Grano repurposes resp as a relation between individuals and propositions. The position taken in this paper represents yet a third variation on this theme, albeit one that is closer in spirit to Farkas’s: a relation between two eventualities.

An anonymous reviewer asks what it means for a state of intention (here, s) located in a particular world (here, w) to cause eventualities in potentially different worlds. A similar issue arises for Kratzer’s (2015) account of transfer of possession verbs, which, like the present proposal, has a causally self-referential component. (Thanks to Paula Menéndez-Benito for drawing my attention to this work.) For example, on Kratzer’s account, a sentence like Peter promised Harriet a rose is true if and only if all worlds compatible with Peter’s promise are worlds where Harriet has a rose as a result of Peter’s promise. In this connection, Kratzer proposes that “all modal alternatives have a duplicate of the modal anchor” (p. 42) (the modal anchor in this case being Peter’s promise). Adopting Kratzer’s suggestion here, we assume that all intention alternatives have a duplicate of that intention that can participate in causal relations.

An anonymous reviewer points out that this approach to intention reports entails a commitment to negative events. In particular, a sentence like Kim intends not to leave would need to be analyzed in a way that involves an intention causing an event of not leaving. For an approach to negative events in compositional semantics that could help carry this out, see Bernard and Champollion 2018.

Here, \(\tau \) represents Krifka’s (1992) temporal trace function from eventualities to their respective runtimes.

This is not to say that the presence or absence of eventuality abstraction is the only factor that regulates mood choice. See Sect. 7 below for a proposal on how to embed this result within a more comprehensive theory of mood choice.

Another possible implementation—suggested to me by Paula Menéndez-Benito (pers. comm.) would be to assume that existential closure over the eventuality argument is effected not by mood itself, but rather by something that sits structurally below indicative mood but above subjunctive. Therefore, indicative complements would necessarily contain this existential closure but not subjunctive complements. And this may fit with independent evidence that subjunctive clauses are smaller than indicative clauses (see, e.g., Giorgi 2004). While I lack the space to assess this possibility here, it may be worth pursuing as an alternative to the implementation sketched here.

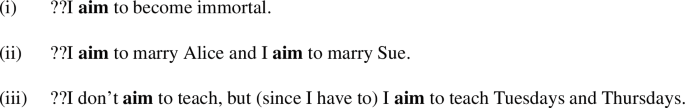

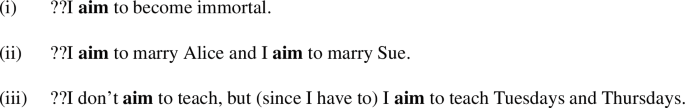

Of course, insofar as goal-oriented predicates like aim have a comparative semantics, their behavior is also captured by comparison-based theories of mood choice. However, it bears noting that at least some of the predicates considered here, just like intend, pattern like hope and unlike want in their logical properties:

In a comparison-based theory like Portner and Rubinstein’s (2020), the difference in mood behavior between aim and hope is unexpected. A theory that recognizes a role for eventuality abstraction in influencing mood choice, however, accommodates these facts.

Earlier precedent in the literature for the idea of action-denoting complements include Lasnik and Fiengo 1974 (who suggest such an analysis for try) and Rochette 1988 (who applies such an analysis to restructuring verbs in French). In a sense, one aim of this paper is to argue for eventuality abstraction as a formal semantic correlate of the more intuitive notion ‘action’.

At first blush, it may look as though (96-b) has an indicative complement paraphrase using should or would, as in (i).

-

(i)

Kim decided that she should/would quit smoking.

However, (96-b) and (i) are not in fact equivalent, as brought out by the non-contradictory status of (ii)-(iii).

-

(ii)

Kim decided to quit smoking, but not that she should/would quit smoking.

-

(iii)

Kim decided that she should/would quit smoking, but did not decide to quit smoking.

(These examples are adapted from Jackendoff 2007, who credits Searle 1983; Jackendoff 1985; Bratman 1987 for the relevant analytical point.) That being said, an anonymous reviewer points out that the data in 94–(95) do not rule out the possibility that (i) is ambiguous between a belief-forming interpretation and an intention-forming interpretation. While I cannot decisively rule out an ambiguity analysis, I think that a more parsimonious account is one in which (i) is unambiguously belief-forming, but conversationally implicates intention formation, on the grounds that a belief that one will or that one should undertake some action is stereotypically accompanied by an intention to do so.

-

(i)

Just as is the case for hybrid attitude predicates, this could be due either to polysemy of the attitude verbs themselves, or due to an appropriately underspecified semantics for the attitude verbs coupled with an appropriately enriched semantics for the complement clauses that would encode the intention interpretation or lack thereof. This choice is orthogonal to the point made here.

Of course, remember can take a (control) infinitival complement, as in (i), but in that case takes on a different, implicative meaning, entailing the prejacent.

-

(i)

Kim remembered to take out the trash.

Baglini and Francez (2016) argue that the implicative verb manage has a causative semantics. If this is right—and if it extends to implicative verbs as a class—then this paper’s core proposal can also explain why implicative verbs accept nonfinite complements in English and subjunctive complements in Greek (see Giannakidou and Mari 2021) but reject finite indicative complements in both languages, insofar as the encoding of causation semantics requires access to the eventuality variable.

-

(i)

Another line of reasoning concerning aspectual predicates, suggested to me by Paula Menéndez-Benito (pers. comm.), is that subjunctive clauses induce obviation in Romance languages, and are therefore incompatible with aspectual predicates because such predicates require co-reference. However, this raises another question: why do aspectual predicates require co-reference? Grano (2016) argues that aspectual predicates require co-reference because the syntactic strategies needed to bring in independent subjects bring along modal meaning that is semantically incompatible with such predicates. If that reasoning is on the right track, then the obviation facts are epiphenomenal, and rooted in principles of modal compatibility.

The status of aspectual predicates with respect to this divide is controversial, given Dowty’s (1977) imperfective paradox. See, e.g., Parsons 1990 for an extensional event-based treatment of aspect and Landman 1992; Portner 1998 for intensional event-based treatments of progressive aspect in particular.

Though see Quer 1997 for a defense of a hypothesis along these lines. Quer argues that the concept of causation underpins part of the distribution of subjunctive clauses, even for predicates for which this is not immediately obvious such as ‘want’.

Note that on this view, what is asserted is not (the characteristic function of) a set of worlds, but rather (the curried characteristic function of) a set of world-time-individual triples. Such objects nonetheless yield truth evaluability as assertions via the assumption that a speaker speaks truly iff the triple consisting of the evaluation world, the speech time, and the speaker is a member of the asserted set. See Pearson 2013, p. 152 for discussion.

This view stands in tension with the view discussed in Sect. 4.3 above that indicative clauses instantiate individual and time argument abstraction optionally or not at all. If we take the position that indicative clauses uniformly instantiate individual and time argument abstraction, then the difference between indicative and subjunctive/nonfinite clauses in terms of the distribution of individual and temporal de se readings would have to be accounted for through some other means, such as in terms of differences in the distribution of de se pronouns; e.g., à la Pearson 2015, PRO is lexically specified to be obligatorily bound by a left-peripheral abstractor (and is therefore obligatorily de se) and can only appear in the subject position of nonfinite clauses, whereas ordinary pronouns like he and she are optionally bound by a left-peripheral abstractor (therefore optionally de se) and can only appear in the subject position of finite clauses. Against the spirit of Sect. 4.3, this alternative approach makes it appear accidental that the very same kinds of clauses that have an affinity for obligatorily abstractor-bound pronouns are also the kinds of clauses that enable eventuality argument abstraction. But a theory naturalizing this connection will have to await another occasion.

Interestingly, this conclusion is roughly the opposite of that of Schlenker (2005), who proposes that, at least in French, subjunctive clauses represent a semantic default. A careful comparison between Schlenker’s theory of mood choice and that in this paper, however, will have to await another occasion.

Portner and Rubinstein’s content(s) is similar though not identical to content(s) from the semantics for intention reports given in (78) and (79) of Sect. 4.2 above. On a technical level, the main difference is that content(s) as defined in (78) above is a set of world-time-individual triples, whereas Portner and Rubinstein’s content(s) is either a modal base or a pair consisting of a modal base and an ordering source, depending on whether s is associated with one or two modal backgrounds.

I assume here that ‘intend’ involves just one modal background and therefore requires sn (simple necessity) rather than ln (local necessity). However, this assumption is not crucial; see note (26) above.

References

Abusch, D. (1997). Sequence of tense and temporal de re. Linguistics and Philosophy, 20, 1–50.

Alonso-Ovalle, L., & Menéndez-Benito, P. (2017). Projecting possibilities in the nominal domain: Spanish uno cualquiera. Journal of Semantics, 35, 1–41.

Anand, P. (2006). De de se. Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Anand, P., & Hacquard, V. (2013). Epistemics and attitudes. Semantics and Pragmatics, 6, 1–59.

Baglini, R., & Francez, I. (2016). The implications of managing. Journal of Semantics, 33, 541–560.

Bernard, T. & Champollion, L. (2018). Negative events in compositional semanitcs. In Maspong, S., Stefánsdóttir, B., Blake, K., and Davis, F., editors, Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 28, pp. 512–532. Linguistic Society of America.

Bogal-Allbritten, E. (2016). Building meaning in Navajo. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Massachusetts.

Bratman, M. E. (1987). Intentions, plans, and practical reason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Buckwalter, W., Rose, D., & Turri, J. (2021). Impossible intentions. American Philosophical Quarterly, 58, 319–332.

Cable, S. (2021). A basic introduction to the semantics of aspect. Lecture notes for Proseminar in Semantic Theory, UMass Amherst, Fall 2021, available at: https://people.umass.edu/scable/LING720-FA21/Handouts/3.Aspect-Basics.pdf.

Champollion, L. (2014). The interaction of compositional semantics and event semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy, 38, 31–66.

Charlow, N. (2013). What we know and what we do. Synthese, 190, 2291–2323.

Chierchia, G. (1989). Anaphora and attitudes de se. In R. Bartsch, J. van Benthem, & P. van Emde Boas (Eds.), Semantics and contextual expression (pp. 1–32). Foris.

Chisholm, R. (1966). Freedom and action. In K. Lehrer (Ed.), Freedom and Determinism (pp. 11–44). Random House.

Condoravdi, C., & Lauer, S. (2016). Anankastic conditionals are just conditionals. Semantics & Pragmatics, 9, 1–61.

Crnič, L. (2011). Getting Even. Ph.D. Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Culicover, P. W., & Jackendoff, R. (2005). Simpler syntax. Oxford University Press.

Dowty, D. (1977). Toward a semantic analysis of verb aspect and the English ‘imperfective progressive’. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1, 45–78.

Dowty, D. (1979). Word meaning and Montague grammar. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Dowty, D. (1985). On recent analyses of the semantics of control. Linguistics and Philosophy, 8, 291–331.

Fara, D. G. (2013). Specifying desires. Noûs, 47, 250–272.

Farkas, D. (1992). On the semantics of subjunctive complements. In P. Hirschbueler & K. Koerner (Eds.), Romance Languages and Modern Linguistic Theory (pp. 69–104). Benjamins.

Giannakidou, A. (1997). The landscape of polarity items. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Groningen.

Giannakidou, A. (1999). Affective dependencies. Linguistics and Philosophy, 22, 367–421.

Giannakidou, A. (2015). Evaluative subjunctive as nonveridicality. In J. Blaszczak, A. Giannakidou, D. Klimek-Jankowska, & K. Migdalski (Eds.), Mood, aspect, modality revisited: New answers to old questions (pp. 177–217). The University of Chicago Press.

Giannakidou, A., & Mari, A. (2021). Truth and veridicality in grammar and thought: Mood, modality and propositional attitudes. University of Chicago Press.

Giannakidou, A., & Staraki, E. (2013). Ability, action, and causation: From pure ability to force. In A. Mari, C. Beyssade, & F. D. Prete (Eds.), Genericity (pp. 250–275). Oxford University Press.

Giorgi, A. (2004). From temporal anchoring to long distance anaphor binding. Paper presented at the 23rd West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. April 23–25, University of California at Davis.

Giorgi, A., & Pianesi, F. (1997). Tense and aspect. Oxford University Press.

Godard, D. (2012). Indicative and subjunctive mood in complement clauses: from formal semantics to grammar writing. In C. Piñon (Ed.), Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics 9 (pp. 129–148). CSSP.

Grano, T. (2016). Semantic consequences of syntactic subject licensing: Aspectual predicates and concealed modality. In Bade, N., Berezovskaya, P., and Schöller, A., editors, Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 20, pp. 306–322. semanticsarchive.

Grano, T. (2017a). Control, temporal orientation, and the cross-linguistic grammar of trying. Glossa, 2(1), 94.

Grano, T. (2017b). The logic of intention reports. Journal of Semantics, 34, 587–632.

Grano, T. (2019). Belief, intention, and the grammar of persuasion. In Ronai, E., Stigliano, L., and Sun, Y., editors, Proceedings of the 54th annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, pp. 125–136. Chicago Linguistic Society, Chicago.

Grano, T. (2022). Enough clauses, (non)finiteness, and modality. Natural Language Semantics, 30, 115–153.

Grano, T., & Phillips-Brown, M. (2022). (Counter)factual want ascriptions and conditional belief. The Journal of Philosophy, 119, 641–672.

Hacquard, V. (2006). Aspects of modality. Ph.D. Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Harman, G. (1976). Practical reasoning. The Review of Metaphysics, 29, 431–463.

Hedman, C. G. (1970). Intending the impossible. Philosophy, 45, 33–38.

Heim, I. (1992). Presupposition projection and the semantics of attitude verbs. Journal of Semantics, 9, 183–221.

Higginbotham, J. (1983). The logic of perceptual reports: An extensional alternative to situation semantics. The Journal of Philosophy, 80, 100–127.

Higginbotham, J. (2003). Remembering, imagining, and the first person. In A. Barber (Ed.), Epistemology of Language (pp. 496–534). Oxford University Press.

Hintikka, J. (1969). Semantics for propositional attitudes. In J. W. Davis, D. Hockney, & W. Wilson (Eds.), Philosophical logic (pp. 21–45). Reidel.

Homer, V. (2007). Intervention effects: The case of presuppositions. Master’s thesis, UCLA.

Huitink, J. (2005). Analyzing anankastic conditionals and sufficiency modals. Student organization of linguistics in Europe (ConSOLE), 13, 135–156.

Huitink, J. (2008). Modals, conditionals and compositionality. Nijmegen: Radboud University Dissertation.

Jackendoff, R. (1985). Believing and intending: Two sides of the same coin. Linguistic Inquiry, 16, 445–460.

Jackendoff, R. (1995). The conceptual structure of intending and volitional action. In Campos, H. and Kempchinsky, P., editors, Evolution and Revolution in Linguistic Theory: Studies in Honor of Carlos P. Otero, pp. 198–227. Georgetown University Press

Jackendoff, R. (2007). Language consciousness culture essays on mental structure. MIT Press.

Jackendoff, R., & Culicover, P. W. (2003). The semantic basis of control in English. Language, 79, 517–556.

Kirkpatrick, C. (1983). What do for-to complements mean? In Chukerman, A., Marks, M., and Richardson, J. F., editors, Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 19. Papers from the nineteenth regional meeting, pp. 214–223. Chicago Linguistic Society, Chicago.

Klein, E., & Sag, I. (1985). Type-driven translation. Linguistics and Philosophy, 8, 163–201.

Kratzer, A. (1991). Modality. In A. von Stechow & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research (pp. 639–650). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1998). More structural analogies between pronouns and tenses. In Strolovitch, D. and Lawson, A., editors, Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory VIII, pp. 92–109. CLC Publications, Cornell University.

Kratzer, A. (2006). Decomposing attitude verbs. Talk given in honor of Anita Mittwoch. The Hebrew University Jerusalem. Handout available at http://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/DcwY2JkM/attitude-verbs2006.pdf.

Kratzer, A. (2015). Creating a family: transfer of possession. Slides for presentation at ‘Modality across categories’, Barcelona, November 5, 2015. Available at https://www.academia.edu/64487615/Creating%20a%20Family%20Transfer%20of%20Possession%20Verbs%20Slides

Krifka, M. (1992). Thematic relations as links between nominal reference and temporal constitution. In I. A. Sag & A. Szabolcsi (Eds.), Lexical Matters (pp. 30–53). Stanford: CSLI.

Landau, I. (2018). Direct variable binding and agreement in obligatory control. In P. Patel-Grosz, P. Grosz, & S. Zobel (Eds.), Pronouns in embedded contexts at the syntax-semantics interface (pp. 1–41). Springer.

Landman, F. (1992). The progressive. Natural Language Semantics, 1, 1–32.

Lasnik, H., & Fiengo, R. (1974). Complement object deletion. Linguistic Inquiry, 5, 535–571.

Lewis, D. (1973). Counterfactuals. Harvard University Press.

Lewis, D. (1979). Attitudes de dicto and de se. The Philosophical Review, 88, 513–543.

Ludwig, K. (1992). Impossible doings. Philosophical Studies, 65, 257–281.

Ludwig, K. (2016). From Individual to Plural Agency. Oxford University Press.

Maier, E. (2011). On the roads to de se. In Ashton, N., Chereches, A., and Lutz, D., editors, Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 21, pp. 393–412. eLanguage.

Morgan, J. (1970). On the criterion of identity for noun phrase deletion. In Proceedings of Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 6, pp. 380–389. CLS, Chicago.

Moulton, K. (2009). Natural selection and the syntax of clausal complementation. PhD dissertation, University of Massachusetts.

Nematollahi, N. (2023). Mood selection in complement clauses in Persian. In Karimi, S., Nematollahi, N., and an Jian Gang Ngui, R. K., editors, Advances in Iranian Linguistics II, pp. 180–209. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Nissenbaum, J. (2005). Kissing Pedro Martinez: (existential) anankastic conditionals and rationale clauses. In Georgala, E. and Howell, J., editors, Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 15, pp. 134–151. Cornell University.

Ogihara, T. (1996). Tense, attitude, and scope. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Ogihara, T. (2007). Tense and aspect in truth-conditional semantics. Lingua, 117, 392–418.

Parsons, T. (1990). Events in the semantics of English: A study of subatomic semantics. MIT Press.

Patel-Grosz, P. (2020). Pronominal typology and the de se/ de re distinction. Linguistics and Philosophy, 43, 537–587.

Pearson, H. (2013). The sense of self: Topics in the semantics of de se expressions. PhD dissertation, Harvard University.

Pearson, H. (2015). The interpretation of the logophoric pronoun in Ewe. Natural Language Semantics, 23, 77–118.

Pearson, H. (2016). The semantics of partial control. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 34, 691–738.

Pearson, H. (2018). Counterfactual de se. Semantics & Pragmatics, 11, 1–41.

Percus, O., & Sauerland, U. (2003a). On the LFs of attitude reports. In Weisberger, M., editor, Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 7, pp. 228–242, Konstanz. Universität Konstanz.

Percus, O., & Sauerland, U. (2003b). Pronoun movement in dream reports. In Kadowaki, M. and Kawahara, S., editors, Proceedings of North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 33, pp. 347–366, Amherst. GLSA.

Phillips-Brown, M. (2019). Anankastic conditionals are still a mystery. Semantics and Pragmatics, 12, 2–17.

Piñango, M. M., & Deo, A. (2016). Reanalyzing the complement coercion effect through a generalized lexical semantics for aspectual verbs. Journal of Semantics, 33, 359–408.

Portner, P. (1992). Situation theory and the semantics of propositional expressions. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Massachusetts.

Portner, P. (1998). The progressive in modal semantics. Language, 74, 760–787.

Portner, P. (2017). On the relation between verbal mood and sentence mood. MS, Georgetown University.

Portner, P. (2018). Mood. Oxford University Press.

Portner, P., & Rubinstein, A. (2012). Mood and contextual commitment. In Chereches, A., editor, Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 22, pp. 461–487. CLC Publications, Ithaca, NY.

Portner, P., & Rubinstein, A. (2020). Desire, belief, and semantic composition: Variation in mood selection with desire predicates. Natural Language Semantics, 28, 343–393.

Quer, J. (1997). In the cause of subjunctive. In J. Coerts & H. D. Hoop (Eds.), Linguistics in the Netherlands 1997 (pp. 171–182). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Reinhart, T. (1990). Self-representation. ms. based on lecture delivered at Princeton conference on anaphora, October 1990.

Rochette, A. (1988). Semantic and syntactic aspects of Romance sentential complementation. Ph.D. Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Rouchota, V. (1994). The semantics and pragmatics of the subjunctive in modern Greek: A relevance-theoretic approach. PhD Dissertation, University College London.

Roussou, A. (2009). In the mood for control. Lingua, 119, 1811–1836.

Rubinstein, A. (2012). Root modalities and attitude predicates. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Rubinstein, A. (2017). Straddling the line between attitude verbs and necessity modals. In A. Arregui, M. L. Rivero, & A. Salanova (Eds.), Modality Across Syntactic Categories (pp. 109–131). Oxford University Press.

Sæbø, K. J. (1985). Notwendige bedingungen im deutschen: Zur semantik modalisierter sätze. Tech. rep. Universität Konstanz, Sonderforschungsbereich 99: Linguistik.

Sæbø, K. J. (2001). Necessary conditions in a natural language. In C. Féry & W. Sternefeld (Eds.), Audiatur vox sapientiae: A Festschrift for Arnim von Stechow (pp. 427–449). Akademie-Verlag.

Schaffer, J. (2016). The Metaphysics of Causation. In Zalta, E. N., editor, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, fall 2016 edition.

Scheffler, T. (2008). Semantic operators in different dimensions. PhD Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Schlenker, P. (2005). The lazy Frenchman’s approach to the subjunctive (speculation on reference to worlds and semantic defaults in the analysis of mood). In Geerts, T., van Ginneken, I., and Jacobs, H., editors, Proceedings of Going Romance XVII, pp. 269–310. John Benjamins.

Schlenker, P. (2011). Indexicality and de se reports. In C. Maienborn, K. von Heusinger, & P. Portner (Eds.), Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning (pp. 1561–1604). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Searle, J. (1983). Intentionality: An Essay in the Philosophy of Mind. Cambridge University Press.

Silk, A. (2018). Commitment and states of mind with mood and modality. Natural Language Semantics, 26, 125–166.

Smirnova, A. (2011). Evidentiality and mood: Grammatical expressions of epistemic modality in Bulgarian. PhD Dissertation, The Ohio State University.

Stephenson, T. (2010). Control in centred worlds. Journal of Semantics, 27, 409–436.

Thomason, R. (2014). Formal semantics for causal constructions. In B. Copley & F. Martin (Eds.), Causation in Grammatical Structures (pp. 58–75). Oxford University Press.

Villalta, E. (2008). Mood and gradability: An investigation of the subjunctive mood in Spanish. Linguistics and Philosophy, 31, 467–522.

von Fintel, K. (1999). NPI-licensing, Strawson-entailment, and context-dependency. Journal of Semantics, 16, 97–148.

von Fintel, K., & Gillies, A. S. (2010). Must...stay ...strong! Natural Language Semantics, 18, 351–383.

von Fintel, K., & Iatridou, S. (2005). What to do if you want to go to Harlem: Anankastic conditionals and related matters MS. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

von Fintel, K., & Iatridou, S. (2023). Prolegomena to a theory of X-marking. Linguistics and Philosophy, 46, 1467–1510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-023-09390-5

von Stechow, A. (1995). On the proper treatment of tense. In Simons, M. and Galloway, T., editors, Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 5, pp. 362–386. Cornell University, Ithaca.

von Stechow, A., Krasikova, S., & Penka, D. (2006). Anankastic conditionals again. In T. Solstand, A. Grønn, & D. Haug (Eds.), A festschrift for Kjell Johan Sæbø: In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the celebration of his 50th birthday (pp. 151–171). Forfatterne.

Wurmbrand, S. (2014). Tense and aspect in English infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry, 45, 403–447.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks go to my language consultants, whose judgments and commentary constitute much of the core data of this paper. These are: Juan Escalona Torres and Karlos Arregi (Spanish); Charlène Gilbert, Fabienne Martin and Barbara Vance (French); Jairo Nunes (Portuguese); Alessia ‘Alex’ Cherici (Italian); Anastasia Giannakidou (Greek), and Mihaela Moreno and Ion Giurgea (Romanian). Earlier versions of the ideas in this paper were presented at the Syntax-Semantics Reading Group at Indiana University, Semantics and Linguistic Theory 31, Agency and Intentions in Language 2, and a Princeton University graduate philosophy seminar on Action Theory. I am grateful to the audiences at all of these venues for their feedback. Finally, thanks go to Linguistics and Philosophy editor Paula Menéndez-Benito and two anonymous reviewers, whose encouragement and constructive criticism helped shape the final version of this paper. Of course, I take full responsibility for any remaining errors and shortcomings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Grano, T. Intention reports and eventuality abstraction in a theory of mood choice. Linguist and Philos 47, 265–315 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-023-09397-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-023-09397-y