Abstract

In this paper, I draw attention to comparative preference claims, i.e. sentences of the form \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \). I show that preference claims exhibit interesting patterns, and try to develop a semantics that captures them. Then I use my account of preference to provide an analysis of desire. The resulting entry for desire ascriptions is independently motivated, and finds support from a wide range of phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A rich source of material for philosophical theorizing concerns the nature of our mental states. A prominent research program in this area tries to shed light on the character of these states by providing a logical, or semantical, account of their expression in natural language. This program focuses on describing the meaning, or truth-conditions, of so-called “propositional attitude reports”. In particular, there has recently been a considerable amount of work on desire ascriptions, for example reports of the form \(\ulcorner \)S wants/hopes/wishes p\(\urcorner \).Footnote 1 In this paper, I aim to contribute to this logico-semantic research agenda in two ways.

My first goal is to draw attention to a closely related, but underdiscussed construction, namely comparative preference claims: sentences of the form \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \).Footnote 2 I show that preference claims exhibit interesting properties, and try to develop an account that captures them. The key idea behind my theory is that preference is alternative-sensitive. This means that the objects relevant for the evaluation of preference claims are certain propositions, called alternatives; and whether p is preferred to q doesn’t just depend on the content of p and q alone, but also on which alternatives are relevant in context.

My second goal is to investigate whether my semantics for preference can help to provide an account of desire. I take inspiration from a fairly long tradition in philosophy that assumes there is a deep connection between preference and desire.Footnote 3 I develop this idea in a novel direction by proposing that the preference-desire connection is reflected in the object language itself. That is, I explore the idea that a desire report \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) means virtually the same as the preference claim \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to \(\lnot \)p\(\urcorner \). The resulting account of desire is elegant and independently motivated. It also allows us to explain a wide range of phenomena.

The paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2 I present a semantics for preference claims, and outline some of its most interesting features. Then in Sect. 3 I use my account of preference to provide a semantics for desire reports. Finally, Sect. 4 raises and responds to some concerns for my approach to preference and desire.

2 Preference

In this section, I put forward my account of preference claims. First, I present some observations that any adequate theory should be able to explain (Sect. 2.1). Then I consider, and reject, some accounts of preference adapted from the existing literature on desire (Sect. 2.2). Finally, I develop my positive proposal, and discuss some important features of this semantics (Sect. 2.3).

2.1 Some observations about preference

Our first set of observations involves closure under entailment. If preference claims were upward monotonic in their first argument, then the following would hold:Footnote 4

Upwardness 1

If \(p \models q\), then \(\textit{S prefers p to r} \models \textit{S prefers q to r}\)

But our first observation is that Upwardness 1 fails. For instance, none of the (ii) examples below follow from the (i) examples:

You preferring prawns to chicken doesn’t mean that you prefer any type of seafood to chicken, e.g. you might well like lobster much less than chicken. Similarly, although preferring winning $100 to winning $50 is rational, (1b-ii) suggests that you prefer losing $100 to winning $50, which isn’t. Finally, for (1c) imagine that when Ann and Carol are together at a party they’re funny, charming and tell great stories. But if one attends without the other, the person attending always ends up being a real bore, and inevitably makes the party worse for everyone else. Then although (1c-i) will be true, (1c-ii) won’t be since Ann’s attending leaves open that she attends without Carol, and you certainly wouldn’t like that.

Similar patterns are exhibited by the second argument of preference claims. If preference claims were upward monotonic in their second argument, then the following would hold:

Upwardness 2

If \(r \models s\), then \(\textit{S prefers p to r} \models \textit{S prefers p to s}\)

But Upwardness 2 also fails. For example, none of the (ii) examples below follow from the (i) examples:

You preferring chicken to lobster doesn’t mean that you prefer chicken to any type of seafood, e.g. you might well like prawns much more than chicken. Similarly, although preferring winning $100 to winning $50 is rational, (2b-ii) suggests that you prefer winning $100 to winning $1000, which isn’t. As for (2c) suppose that when Ann attends a party alone (i.e. without Carol) she’s funny, charming and tells great stories. But if she and Carol attend together, they always end up being a real bore, and inevitably make the party worse for everyone else. Then although (2c-i) will be true, (2c-ii) won’t be since Ann’s attending leaves open that she attends without Carol, and you’d prefer this to neither attending.

Our second cluster of observations concerns downward monotonicity. If preference claims were downward monotonic in their first argument, then the following would hold:

Downwardness 1

If \(p \models q\), then \(\textit{S prefers q to r} \models \textit{S prefers p to r}\)

We observe that Downwardness 1 has something of a mixed status: a fairly wide range of phenomena provide support for the principle, but there are also cases which suggest that Downwardness 1 cannot be unrestrictedly valid.

On the one hand, the (ii) examples below can be legitimately inferred from the (i) examples:

Moreover, conjoining the (i) examples in (3) with the negation of the (ii) examples leads to infelicity. For instance, both (4a) and (4b) are unacceptable (as indicated by the ‘#’ preceding each example):

This is exactly what we would expect if Downwardness 1 was valid, and the (i) examples entailed the (ii) examples.

Further support for Downwardness 1 comes from the fact that if p and q are related by entailment, then \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is unacceptable. For instance, (5) is infelicitous:

Downwardness 1 provides us with a neat explanation of why this should be. If (5) was true, then by Downwardness 1 ‘You prefer getting prawns to getting prawns’ would be true as well. But we can assume that nothing can be preferred to itself. So, (5) must be false.

On the other hand, Downwardness 1 cannot be unrestrictedly valid. For instance, (6b) does not follow from (6a):

You preferring seafood to chicken doesn’t mean that you prefer seafood along with an arbitrarily bad outcome, for example having your house burn down, to chicken. But You get seafood and your house burns down obviously entails You get seafood.

The same patterns are exhibited by the second argument of preference claims. The relevant principle here is Downwardness 2:

Downwardness 2

If \(r \models s\), then \(\textit{S prefers p to s} \models \textit{S prefers p to r}\)

Once again, a wide range of phenomena provide support for Downwardness 2, but there are also cases which suggest that it cannot be unrestrictedly valid.

On the one hand, the (ii) examples below seem to follow from the (i) examples:

Also, Downwardness 2 provides a neat explanation for why the examples in (8) are unacceptable:

If (7a-i) entails (7a-ii), then (8a) cannot be true. And if Downwardness 2 holds, then (8b) entails ‘You prefer getting prawns to getting prawns’, but presumably the latter cannot be true.

On the other hand, (9a) does not entail (9b):

You preferring chicken to seafood doesn’t mean that you prefer chicken to seafood along with an arbitrarily good outcome, for example winning one million dollars. But You get seafood and you win one million dollars obviously entails You get seafood.

At this point, it is worth pausing to address some concerns raised by a reviewer involving the contention that preference claims are (restrictedly) downward monotonic in both their arguments. First, the reviewer argues that if the arguments of preference claims are downward monotone, then they should license weak negative polarity items (NPIs) such as ‘any’ and ‘ever’. However, the reviewer observes that although the second argument seems to license these expressions, NPIs sound degraded when they appear in the first argument:

In response, it is worth pointing out that there is a healthy debate about the correctness of monotonicity-based approaches to NPI licensing, and alternative licensing conditions have been developed.Footnote 5 So, the existence of a straightforward connection between downward monotonicity and NPI licensing shouldn’t necessarily be taken for granted. Moreover, even those who tie NPI licensing to monotonicity tend not to take downward monotonicity as sufficient for NPI licensing. Rather, they only take it to be a necessary condition.Footnote 6 Indeed, there are well-known counterexamples to sufficiency. For example, the restrictor arguments of the quantifiers ‘each’, ‘both’ and ‘the’ are all standardly taken to be (restrictedly) downward monotonic environments,Footnote 7 but these positions fail to license NPIs:

So, although it is worth investigating why the second argument of preference reports more readily accepts NPIs than the first argument, this doesn’t undermine the claim that both positions are restrictedly downward monotone.

Second, the reviewer suggests that some of the data I have canvassed in support of downward monotonicity could be explained by other means. In particular, they point out that disjunctions inside the scope of certain modal expressions are independently known to have a distributive effect. For instance, consider the so-called “free choice” phenomenon that arises when disjunctions are embedded inside possibility modals, e.g. epistemic ‘might’:

An utterance of (12a) implies (12b), i.e. (12a) suggests both that your winning a car is epistemically possible, and that your winning a caravan is epistemically possible.Footnote 8 The idea is that whatever mechanism is responsible for the distribution effect in (12a) is also responsible for this effect in examples such as (3b-ii) (‘You prefer winning a car or a boat to winning a caravan’).

I am sympathetic to the thought that disjunction has special properties. But I will leave it to others to try to use non-Boolean analyses of disjunction in order to explain examples such as (3b-ii).Footnote 9 This is because a response that simply appeals to the special properties of disjunction won’t provide us with a complete account of our observations. As we have seen above, the data motivating downward monotonicity for preference go beyond cases which feature explicit disjunction, e.g. the inference from (3b-i) (‘You prefer seafood to chicken’) to (3b-ii) (‘You prefer prawns to chicken’).Footnote 10 Here are some further examples:

These inferences seems robust. But neither (13a) nor (14a) involves disjunction, and so presumably these inferences can’t arise from a free choice effect. Indeed, note that the corresponding inferences with ‘might’ are much less good:

To summarize our observations: although preference claims aren’t unrestrictedly downward monotonic, downward monotonicity has a positive status not shared by upward monotonicity. This requires explanation, and the remainder of this section tries to satisfy this demand. I present my preferred account in Sect. 2.3. But before we get there, in the next subsection I consider two analyses of preference adapted from dominant theories of desire reports. These entries aren’t able to capture our observations, but their failures will be instructive.

2.2 Two attempts at a semantics for prefer

As mentioned in Sect. 1, preference claims have been given little attention in the literature on desire. But it might be thought that existing accounts of desire could be adapted to provide an analysis of preference. The extant literature is dominated by two sorts of accounts: (i) theories that analyze desire in terms of a subjective ordering over possible worlds (von Fintel , 1999; Rubinstein , 2012; Crnič , 2011); and (ii) decision-theoretic analyses that tie the desirability of a proposition to its expected value (Levinson , 2003; Lassiter , 2011; Phillips-Brown , 2021). I briefly consider natural extensions of these accounts to preference below.

2.2.1 Best worlds accounts

Best worlds analyses of desire involve two main elements: (i) a domain of worlds, or modal base \({\mathcal {B}}\), and (ii) a subjective ordering \(>_{S, w}\) over the worlds in \({\mathcal {B}}\).Footnote 11 The idea is that \(w' >_{S, w} w''\) when \(w'\) is more desirable to S (in w) than \(w''\).Footnote 12\(>_{S, w}\) is taken to be a strict partial order. The desirability of a proposition is usually measured by considering the top-ranked worlds in \({\mathcal {B}}\), as ordered by \(>_{S, w}\) (von Fintel , 1999). Since a preference claim \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) involves a comparison between p and q, simply considering the top-ranked worlds in \({\mathcal {B}}\) won’t be very helpful. For instance, even if all the top-ranked worlds are \(\lnot p \wedge \lnot q\)-worlds, \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) can still be true. One idea is that instead of considering the top-ranked worlds tout court, we should compare the top-ranked p-worlds to the top-ranked q-worlds. To make this a bit more precise, let us introduce a function \(\textsc {best}(\cdot )\) that takes a proposition p and yields the set of top-ranked p-worlds in \({\mathcal {B}}\), as ordered by \(>_{S, w}\).Footnote 13 Then the entry for ‘prefer’ is as follows:Footnote 14

Best worlds semantics for prefer

\(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is true relative to \(\langle w, {\mathcal {B}} \rangle \) iff for all \(w' \in \textsc {best}(p)\), and for all \(w'' \in \textsc {best}(q)\): \(w' >_{w, S} w''\)

In short, \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is true just in case every top-ranked p-world is preferred to any top-ranked q-world.

I have a general worry with this semantics, and also some more specific concerns relating to our observations in Sect. 2.1. The broad worry can be brought out by considering the following example adapted from Levinson (2003):

Insurance: Sue is deciding whether to take out house insurance. She estimates that the chances of her house burning down are \(\frac{1}{1000}\). But the results would be calamitous: she’d lose her home which is valued at \(\$1,000,000\). Comprehensive home insurance would cost her \(\$100\). Sue has a meeting with her insurance broker this afternoon, so she needs to decide what she would like to do.

If Sue is like most of us, (17) is true: even though she thinks it’s likely that her house won’t burn down, there is a small possibility that it does, and the badness of this possibility outweighs the cost of buying insurance. But the best worlds semantics seems to predict that (17) should be false: the best worlds in which Sue buys insurance are not better than the best worlds in which she doesn’t buy insurance, since Sue most prefers worlds where she spends no money on insurance (and there’s no fire). Examples such as (17) suggest that the relevant preference calculation shouldn’t be done at the level of individual worlds, but rather at a coarser grain, e.g. at the level of whole propositions.

The best worlds semantics also fails to capture our observations from Sect. 2.1. For one thing, although it doesn’t make preference claims fully upward monotonic, it still makes problematic predictions. Suppose that \({\mathcal {B}}\) consists of three worlds: \(w_{\textsc {c}}, w_{\textsc {p}}, w_{\textsc {l}}\), where \(w_{\textsc {c}}\) is the world where you get chicken, \(w_{\textsc {p}}\) is the world where you get prawns, and \(w_{\textsc {l}}\) is the world where you get lobster. Suppose that you love prawns, find chicken to be average, and hate lobster because you’re allergic to it. Then your ranking of these worlds looks as follows:

\(w_{\textsc {p}}>_{\text {You}} w_{\textsc {c}} >_{\text {You}} w_{\textsc {l}}\)

Then (3a-ii) (‘You prefer prawns to chicken’) is predicted to be true, since \(w_{\textsc {p}} >_{\text {You}} w_{\textsc {c}}\). But (3a-i) (‘You prefer seafood to chicken’) is also predicted to be true, since best(You get prawns) = best(You get seafood) = \(w_{\textsc {p}}\). But intuitively (3a-i) is not true in this context.

The best worlds semantics also renders Downwardness 1 and Downwardness 2 straightforwardly invalid, and fails to explain why these principles appear to have a positive status. For instance, although (3a-i) is true in the scenario sketched above, ‘You prefer lobster to chicken’ is false. Moreover, it allows \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) to be true even when p and q are related by entailment. For example, ‘You prefer getting seafood to getting lobster’ is predicted to be true in context.Footnote 15

2.2.2 Decision-theoretic accounts

Now let us turn to the decision-theoretic approach to desire. On this proposal, the desirability of a proposition for a subject S is tied to the expected value of this proposition for S (Levinson , 2003). The expected value of p for S is the utility of p for S weighted by S’s subjective probabilities (Jeffrey , 1965). Given this framework, a natural thought is that S prefers p to q when the expected value of the former is greater than the expected value of the latter:Footnote 16\(^{,}\)Footnote 17

Decision-theoretic semantics for prefer

\(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is true in w iff \(EV_{w,S}(p) > EV_{w,S}(q)\)

This account renders both Upwardness 1 and Upwardness 2 invalid. But it fails to explain the rest of our observations from Sect. 2.1. For instance, it allows \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) to be true even when p and q are related by entailment. Suppose once again that you will be given lobster, prawns or chicken. You really like prawns, you think chicken is average, and you hate lobster. Then we can assign utilities to these outcomes so that (8b) (‘You prefer getting prawns to getting seafood’) is predicted to be true. For instance, suppose your credences/utilities are as follows:

A routine exercise confirms that \(EV_{\text {You}}(\textit{You get prawns}) > EV_{\text {You}}(\textit{You get prawns or} \textit{lobster}) = EV_{\text {You}}(\textit{You get seafood})\). Thus, (8b) will be true.

It is worth remarking that although the decision-theoretic semantics fails to provide us with an adequate account of preference claims, I still think that decision-theoretic considerations impact preference. But as we will see in Sect. 2.3, this involves something more subtle than a simple expected value calculation of the arguments to ‘prefer’.

To sum up, we have considered two accounts of preference, both of which are extensions of popular approaches to desire, and found these accounts to be lacking. Our discussion provides us with sufficient motivation to consider a different approach, which is what I take up next.

2.3 An alternative-sensitive semantics for prefer

I develop my positive proposal in two stages. First, I provide a basic entry that captures some of the central features of my account. Then I propose a refinement that will help us generate a pleasing logic for preference.

Let us say that \({\mathcal {A}}\) is a set of alternatives if it is a set of pairwise incompatible propositions. So, if \(A, B \in {\mathcal {A}}\), then \(A \cap B = \emptyset \). To illustrate, let ann, mary, pete, and sue represent the propositions that Ann wins the race, Mary wins the race, Pete wins the race, and Sue wins the race, respectively. Then \({\mathcal {A}}_{1} = \{\) ann, mary, pete, sue\(\}\) is a set of alternatives. I propose that the set of objects that is relevant for the evaluation of a preference claim \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is a set of contextually supplied alternatives.Footnote 18\(^{,}\)Footnote 19

Given a set of alternatives \({\mathcal {A}}\) and a world w, \({\mathcal {O}}^{{\mathcal {A}}, w}(\cdot )\) is an ordering function from individuals to orderings over \({\mathcal {A}}\). It is assumed that \({\mathcal {O}}^{{\mathcal {A}}, w}(S)\) is a strict partial order. Intuitively, \({\mathcal {O}}^{{\mathcal {A}}, w}(S)\) represents S’s preference ordering over \({\mathcal {A}}\) in w, denoted \(\succ _{w, S}\). For instance, Bill’s preferences over \({\mathcal {A}}_{1}\) are represented below:

ann \(\succ _{\text {Bill}}\) mary \(\succ _{\text {Bill}}\) pete \(\succ _{\text {Bill}}\) sue

I propose that preference claims are evaluated relative to a contextually determined ordering function.

My first-run account of preference can then be expressed as follows:

Account 1

\(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is true relative to \(\langle w, {\mathcal {A}}, {\mathcal {O}} \rangle \) iff

for every \(B \in {\mathcal {A}}\) such that \(B \subseteq p\), and every \(C \in {\mathcal {A}}\) such that \(C \subseteq q\): \(B \succ _{w, S} C\)

In short: \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is true just in case S ranks every p-entailing alternative more highly than every q-entailing alternative. It is worth emphasizing that this semantics is in some sense strong: every p-entailing alternative and every q-entailing alternative is relevant for the assessment of a preference claim. So, it is sufficient for \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) to be false that that there is some p-entailing alternative that fails to be more highly ranked than some q-entailing alternative. Note, however, that the fact that preferences are computed over propositions rather than individual worlds means that this semantics isn’t implausibly strong. It is not required that subjects prefer every p-world to every q-world. As we saw in Sect. 2.2.1, this would be problematic: Sue can prefer buying insurance to not buying insurance, even if most worlds where she buys insurance are worse, by her lights, than most worlds she doesn’t buy insurance. By contrast, alternatives are relatively coarse-grained entities. So, even if there are some worlds in an alternative B that are non-optimal by S’s lights, S can still rank B higher than the other alternatives.

At this point, two natural meta-semantic questions arise for Account 1: (i) how exactly does the set of alternatives \({\mathcal {A}}\) get determined in context, and (ii) how is the subject’s ordering over alternatives \(\succ _{S}\) structured?Footnote 20 Regarding (ii), I’m attracted to the idea that the subject’s ordering is tied to decision-theoretic considerations. Most straightforwardly: \(A \succ _{S} B\) when \(EV_{S}(A) > EV_{S}(B)\). Assuming that the relevant alternatives in the Insurance scenario are just the proposition that Sue buys insurance and the proposition that she does not, this would explain why (17) (‘Sue prefers buying insurance to not buying insurance’) is true: the expected value of buying insurance, for Sue, is greater than the expected value of not buying insurance. As for (i), I will return to this issue in Sect. 4.2. For now, I want to discuss which features are exhibited by preference claims when we fix a context, and thereby fix a set of relevant alternatives and ordering over these alternatives. That is, our present concern is to detail the logic of preference.

Account 1 allows us to explain failures of upward monotonicity. Suppose that the relevant set of alternatives is \({\mathcal {A}} = \{\textsc {p}, \textsc {l}, \textsc {c}\}\), where p is the proposition that you get prawns, \(\textsc {l}\) is the proposition that you get lobster, and c is the proposition that you get chicken. Let us also suppose that your preferences over these alternatives look as follows:

p \(\succ _{\text {You}}\) \(\textsc {c}\) \(\succ _{\text {You}}\) \(\textsc {l}\)

Then (1a-i) (‘You prefer prawns to chicken’) is true, since p is ranked above every other alternative. However, (1a-ii) (‘You prefer seafood to chicken’) is false, since l entails that you get seafood, but it is ranked below c. Similarly, (2a-i) (‘You prefer chicken to lobster’) is true, since c is ranked above l. However, (2a-ii) (‘You prefer chicken to seafood’) is false, since p entails that you get seafood, but it is ranked above c. The other examples from Sect. 2.1 involving failures of disjunction introduction and conjunction elimination can be explained in a similar way.

However, Account 1 doesn’t quite capture our observations about downward monotonicity. The problem is that the logic it generates is too strong; it makes preference claims straightforwardly downward monotonic in both arguments. This has some good consequences, e.g. it predicts that (3a-i) entails (3a-ii), which explains why the latter seems to follow from the former:

After all, if every seafood-entailing alternative is ranked above every chicken-entailing alternative, then every prawns-entailing alternative will be ranked above every chicken-entailing alternative.

On the other hand, in Sect. 2.1 we saw that preference claims aren’t unrestrictedly downward monotonic. For instance, (6b) does not follow from (3a-i):

But (3a-i) also entails (6b) on Account 1: if every seafood-entailing alternative is ranked above every chicken-entailing alternative, then every seafood \(\wedge \) house burns down-entailing alternative will be ranked above every chicken-entailing alternative.

What examples such as (6b) show is that p and q need to be suitably related to \({\mathcal {A}}\) in order for \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) to be true. I will capture this as follows. Given a set of alternatives \({\mathcal {A}}\) and proposition p, let us say that p is represented by \({\mathcal {A}}\) just in case every alternative in \({\mathcal {A}}\) either entails p or entails \(\lnot p\).Footnote 21 For instance, the proposition that Ann or Mary wins the race is represented by \({\mathcal {A}}_{1} = \{\) ann, mary, pete, sue\(\}\), but the proposition that Mary eats pizza is not. And given a set of alternatives \({\mathcal {A}}\) and proposition p, let us say that p is non-trivially represented by \({\mathcal {A}}\) just in case (i) p is represented by \({\mathcal {A}}\), and (ii) there is some p-entailing alternative in \({\mathcal {A}}\).

I propose that \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is true only if both p and q are non-trivially represented by \({\mathcal {A}}\). One could impose this requirement as a regular truth-condition. However, I will instead treat it as a definedness condition, or presupposition, triggered by preference claims. The main reason for going this route is that it allows us to develop a pleasing logic for preference, which I will outline in a moment. The final entry for ‘prefer’ then looks as follows:

Alternative-sensitive semantics for prefer

\(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is defined relative to \(\langle w, {\mathcal {A}}, {\mathcal {O}} \rangle \) only if

both p and q are non-trivially represented by \({\mathcal {A}}\)

If defined, \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is true relative to \(\langle w, {\mathcal {A}}, {\mathcal {O}} \rangle \) iff

for every \(B \in {\mathcal {A}}\) such that \(B \subseteq p\), and every \(C \in {\mathcal {A}}\) such that \(C \subseteq q\): \(B \succ _{w, S} C\)

In our discussions of upward and downward monotonicity, I (implicitly) assumed a classical notion of validity which requires preservation of truth at a point of evaluation. But now that we have presuppositions as part of the meaning of preference claims, more sophisticated notions of consequence can be formulated. More specifically, the notion that will be of particular relevance is that of Strawson validity (von Fintel , 1999). Essentially, an argument from a set of sentences \(\Gamma \) to a sentence \(\psi \) is Strawson valid just in case whenever all of the \(\varphi \in \Gamma \) and \(\psi \) are defined, if all of the \(\varphi \in \Gamma \) are true, then \(\psi \) must be true as well. A bit more explicitly:Footnote 22

Strawson Validity:

\(\Gamma \models \psi \) iff there is no context c and world w such that (i) every \(\varphi \in \Gamma \) and \(\psi \) are all defined at c, w; (ii) every \(\varphi \in \Gamma \) is true at c, w; and (iii) \(\psi \) is false at c, w.

On this alternative-sensitive semantics, preference claims are Strawson downward monotonic in both of their arguments. That is, Downwardness holds:

Downwardness

If \(p \models q\) and \(r \models s\), then \(\textit{S prefers q to s} \models \textit{S prefers p to r}\)

Suppose \(\ulcorner \)S prefers q to s\(\urcorner \) is true, and \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to r\(\urcorner \) is defined. Consider some arbitrary p-entailing alternative B, and some arbitrary r-entailing alternative C (such alternatives must exist since both p and r are non-trivially represented). Because \(p \subseteq q\) and \(r \subseteq s\), B entails q, and C entails s. Since \(\ulcorner \)S prefers q to s\(\urcorner \) is true, we must have \(B \succ _{S} C\). But then since B and C were arbitrary, \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to r\(\urcorner \) must be true as well.

Downwardness allows us to explain our remaining observations from Sect. 2.1. In the most natural contexts where (3a-i) (‘You prefer seafood to chicken’) is assessed, the proposition that you get prawns will be non-trivially represented by the relevant set of alternatives. Thus, since Downwardness holds, if (3a-i) is true, (3a-ii) (‘You prefer prawns to chicken’) will be true as well. However, in these same contexts, (3a-i) can be true without (6b) (‘You prefer seafood and having your house burned down to chicken’) being true: the proposition that you get seafood and your house burns down won’t be (non-trivially) represented by the relevant set of alternatives. For instance, if \({\mathcal {A}} = \{\textsc {p}, \textsc {l}, \textsc {c}\}\) from above, then if (3a-i) is true, (3a-ii) will be true as well. But (6b) won’t be defined, since some alternatives in \({\mathcal {A}}\) entail neither You get seafood and your house burns down nor \(\lnot \)You get seafood and your house burns down.Footnote 23

Moreover, we can explain why examples such as (4a) and (5) are unacceptable:

If both conjuncts in (4a) are defined, then since Downwardness holds, the second conjunct will be false if the first conjunct is true. And if one of the conjuncts isn’t defined, then the whole conjunction will fail to be defined.Footnote 24 So, (4a) can never be true. For (5), we observe that preference claims are irreflexive on this semantics:Footnote 25

Irreflexivity

\(\models \lnot \textit{S prefers p to p}\)

So, if (5) is defined, then given Downwardness it will be false. And if (5) isn’t defined then of course it cannot be true. In any event, (5) cannot be true.

Strawson entailment also allows us to validate several further patterns which are arguably necessary conditions for a subjective ordering to be considered a preference relation:Footnote 26

Transitivity

\(\textit{S prefers p to q}, \textit{S prefers q to r} \models \textit{S prefers p to r}\)

Asymmetry

\(\textit{S prefers p to q} \models \lnot \textit{S prefers q to p}\)

We also validate the following intuitively plausible principles:Footnote 27\(^{,}\)Footnote 28

Preference Weakening 1

\(\textit{S prefers p to q}, \textit{S prefers r to q} \models \textit{S prefers p or r to q}\)

Preference Weakening 2

\(\textit{S prefers p to q}, \textit{S prefers p to r} \models \textit{S prefers p to q or r}\)

I’lll close this section with a possible concern for my approach to preference involving indifference claims, i.e. sentences of the form \(\ulcorner \)S is indifferent between p and q\(\urcorner \).Footnote 29 A prima facie plausible principle linking preference to indifference is the following:

Preference-to-Indifference

\(\lnot \textit{S prefers p to q}, \lnot \textit{S prefers q to p} \models \textit{S is indifferent} \textit{between p and q}\)

That is, a lack of preference in either direction between p and q is sufficient for the truth of the corresponding indifference claim. However, my semantics appears to invalidate this pattern. Consider our running seafood example once again, where your preferences over the alternatives are as follows: p \(\succ _{\text {You}}\) \(\textsc {c}\) \(\succ _{\text {You}}\) \(\textsc {l}\). Then on my entry both ‘You don’t prefer seafood to chicken’ and ‘You don’t prefer chicken to seafood’ are true (relative to the most natural set of alternatives). However, (20) doesn’t seem acceptable in context:Footnote 30

In response, I maintain that such cases do indeed bring natural counterexamples to Preference-to-Indifference. In the seafood example, it would be natural for you to say something like ‘I don’t prefer seafood to chicken, since lobster is much worse than chicken, and I don’t prefer chicken to seafood, since prawns are much better than chicken, but I also wouldn’t say that I’m indifferent between seafood and chicken’. Such contexts illustrate that a lack of preference isn’t sufficient for indifference, and that natural language expressions of indifference denote a more substantial mental state than we might have antecedently assumed. One proposal for indifference claims set in the alternative-sensitive framework that makes good on this idea is the following:

Alternative-sensitive semantics for indifference

\(\ulcorner \)S is indifferent between p and q\(\urcorner \) is defined relative to \(\langle w, {\mathcal {A}}, {\mathcal {O}} \rangle \) only if

both p and q are non-trivially represented by \({\mathcal {A}}\)

If defined, \(\ulcorner \)S is indifferent between p and q\(\urcorner \) is true relative to \(\langle w, {\mathcal {A}}, {\mathcal {O}} \rangle \) iff

for every \(B \in {\mathcal {A}}\) such that \(B \subseteq p\), and every \(C \in {\mathcal {A}}\) such that \(C \subseteq q\): \(B \not \succ _{w, S} C\) and \(C \not \succ _{w, S} B\)

In other words, a subject is indifferent between p and q only if no p-entailing alternative outranks any q-entailing alternative, and no q-entailing alternative outranks any p-entailing alternative. This is why (20) is false in the seafood context: the You get chicken-entailing alternative “splits” the You get seafood-entailing alternatives.

However, note that although this account of indifference invalidates Preference-to-Indifference, it is straightforward to check that it validates its converse:

Indifference-to-Preference

\(\textit{S is indifferent between p and q} \models \lnot \textit{S prefers p to q}\)

That is, being indifferent between p and q suffices for a lack of preference in either direction. This is a good result, since Indifference-to-Preference appears to be much more robust than Preference-to-Indifference.Footnote 31\(^{,}\)Footnote 32

In this section, we began with some observations about preference claims. I then developed an account of preference whose crucial features are (i) preference claims are alternative-sensitive, and (ii) the semantics is strong: in order for \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) to be true, every p-entailing alternative needs to be more highly ranked than every q-entailing alternative. I showed that this entry allows us to explain our initial observations, and gives rise to an intuitive logic for preference. In particular, this account explains the positive status of downward monotonicity without making it unrestrictedly valid; on my theory preference claims are Strawson, but not classically, downward monotonic. In the next section, I turn to desire reports, and explore whether the semantics for preference can help us develop an account of want ascriptions.

3 Desire

I begin by presenting an entry for ‘want’ that is inspired by my entry for ‘prefer’ (Sect. 3.1). Then I consider the logic that this semantics generates, and show that the proposal explains a wide range of phenomena that isn’t captured by existing accounts (Sect. 3.2).

3.1 An alternative-sensitive semantics for want

As mentioned in Sect. 1, many philosophers have assumed that there is a deep connection between preference and desire. I develop this thought in a novel direction by proposing that the preference-desire connection is in some sense reflected in the object language itself. More precisely, I want to explore the idea that a desire report \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) means virtually the same as the preference claim \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to \(\lnot \)p\(\urcorner \). We can find some intuitive motivation for this proposal if we consider how we tend to justify our desires: in providing reasons for why one wants or desires p, it is natural to appeal to one’s preference for p over the other relevant options. For example, (21b) is a perfectly natural answer to the question in (21a):

Moreover, in many contexts, \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) and \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to \(\lnot \)p\(\urcorner \) seem virtually synonymous. For instance, consider (22a) and (22b):

It is difficult to recover coherent interpretations of these sentences, which is what we would expect if desire reports and preference claims share an underlying semantics.Footnote 33

Supposing that \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) means the same as \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to \(\lnot \)p\(\urcorner \), and given our entry for ‘prefer’, the entry for desire reports is then the following:Footnote 34

Alternative-sensitive semantics for want

\(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) is defined relative to \(\langle w, {\mathcal {A}}, {\mathcal {O}} \rangle \) only if

both p and \(\lnot p\) are non-trivially represented by \({\mathcal {A}}\)

If defined, \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) is true relative to \(\langle w, {\mathcal {A}}, {\mathcal {O}} \rangle \) iff

for every \(B \in {\mathcal {A}}\) such that \(B \subseteq p\), and every \(C \in {\mathcal {A}}\) such that \(C \subseteq \lnot p\): \(B \succ _{w, S} C\)

\(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) is defined only if both p and \(\lnot p\) are non-trivially represented by the set of relevant alternatives. If defined, \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) is true just in case S ranks every p-entailing alternative above every \(\lnot p\)-entailing alternative. As with our account of preference, every p-entailing alternative and every q-entailing alternative is relevant for evaluating a desire report. So, if defined, it is sufficient for \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) to be false that there is some p-entailing alternative that fails to be more highly ranked than some \(\lnot p\)-entailing alternative.

It is worth pausing to bring out a feature of this semantics. Almost all existing accounts of desire posit a close connection between what is desired and what is believed. More precisely, most accounts posit the following constraint: \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) is true only if S neither believes p nor \(\lnot p\) (Heim , 1992; von Fintel , 1999; Levinson , 2003).Footnote 35 By contrast, nowhere in my semantics for ‘want’ do I appeal to the subject’s beliefs. I take this to be a good-making feature of the entry. It has been recognized for some time (though it is often ignored) that subjects can want things that they are certain won’t obtain, as well as things that they are certain do obtain/will obtain:

These examples are perfectly felicitous, but they are difficult to account for given standard belief constraints on want ascriptions.Footnote 36 But my semantics has no problem with these cases, since I place no restrictions on what the set of alternatives needs to be like.

Note that my account is compatible with the idea that in many situations, the relevant alternatives for evaluating \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) will be things that S believes might obtain. But what the above examples show is that this isn’t always the case, and therefore shouldn’t be built into our semantics for want reports. Also, denying that there is a strong connection between believing and wanting is compatible with there being more subtle relationships between these states. For instance, beliefs could still play a role in explaining the way presuppositions project from desire contexts (Heim , 1992; Maier , 2015). Finally, claiming that ‘want’ does not carry strong belief requirements is compatible with thinking that other desire verbs do. For instance, analogues of the examples in (23) with ‘hope’ sound much worse:

This suggests that hope reports impose non-trivial constraints on the subject’s beliefs. We can capture such constraints if we introduce the following concept: given a subject S and world w, \(\hbox {Dox}_{w, S}\) is S’s belief set in w; the set of worlds compatible with everything S believes in w (Hintikka , 1962). Then we can say that hope reports carry an additional definedness condition: each alternative in \({\mathcal {A}}\) must have non-empty intersection with \(\hbox {Dox}_{w, S}\).Footnote 37 It is plausible that the meaning of other desire verbs, e.g. ‘wish’, can also be understood as variants of my semantics for ‘want’. But I’ll leave charting these fine-grained differences between desire verbs for future work. For the most part I’ll continue to focus on want reports.

Now that I have presented my account of desire, let us consider some of its most interesting logical properties.

3.2 The logic of desire

First, we have a number of closure failures: want reports are neither upward nor downward monotonic.

Not Up

There are p, q such that \(p \subseteq q\), but \(\textit{S wants p} \not \models \textit{S wants q}\)

Not Down

There are p, q such that \(p \subseteq q\), but \(\textit{S wants q} \not \models \textit{S wants p}\)

Such failures have been discussed a great deal in the literature on desire reports.Footnote 38 Not Up can be illustrated by considering the following case that is essentially from Levinson (2003):

Flip: Bill has agreed to play a game involving two coin flips. If the first coin lands heads, the game ends and Bill is given $200. If the first coin lands tails, then the second coin is flipped. If the second coin lands tails then the game ends and Bill gets $300, but if the second coin lands heads then the game ends and Bill gets nothing. That is, the outcomes are as follows: H = $200, TT = $300, TH = $0.

Although (26a) seems true, (26b) does not. After all, if the first coin lands tails, then Bill knows there’s a good chance he’ll get nothing. We can explain this if we suppose that the relevant set of alternatives is \({\mathcal {A}} = \{\textsc {h}, \textsc {tt}, \textsc {th}\}\), where h is the proposition that the first coin lands heads, \(\textsc {tt}\) is the proposition that both coins land tails, and \(\textsc {th}\) is the proposition that the first coin lands tails and the second lands heads. Bill’s ranking of these alternatives looks as follows:

tt \(\succ _{\text {Bill}}\) \(\textsc {h}\) \(\succ _{\text {Bill}} \textsc {th}\)

Then we predict that (26a) should be true, since tt is ranked above every other alternative. But (26b) is false, since \(\textsc {th}\) entails that the first coin lands tails, but it is ranked below \(\textsc {h}\). It is worth saying that although most existing accounts of desire make want reports non-monotonic, examples such as (26) are fairly controversial. Most notably, von Fintel (1999) has argued that desire is upward monotonic after all. We will consider his arguments in Sect. 4.1.

Note that even if p entails q, our semantics allows \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) to be true without \(\ulcorner \)S wants q\(\urcorner \) even being defined. This can account for Stalnaker’s (1984) observation that (27a) can be true without (27b) being true:

It is plausible that in most natural contexts, the relevant alternatives for evaluating (27a) will just be the proposition that I die peacefully, and the proposition that I die painfully. In that case, (27b) will be undefined, since there will be no alternatives that entail that I don’t die.

To illustrate Not Down, suppose that you are choosing between buying a Honda car, a Ford car, and a Vespa scooter. Scooters are dangerous, so you like the Vespa the least. Hondas have a reputation for being safe, so you like that the best. Then (28a) is true, but (28b) is not:

Let us suppose that the set of alternatives is \({\mathcal {A}} = \{\textsc {h}, \textsc {f}, \textsc {v}\}\), where h is the proposition that you buy a Honda car, f is the proposition that you buy a Ford car, and v is the proposition that you buy a Vespa scooter. Your ranking over these alternatives is as follows:

h \(\succ _{\text {You}}\) \(\textsc {f}\) \(\succ _{\text {You}} \textsc {v}\)

Then (28a) is true, since both h and f outrank v. But (28b) is false, since h entails that you don’t buy a Ford, and yet is ranked above f.

Another important fact is that desire isn’t closed under believed equivalence:

No Belief Closure

\(\textit{S wants p}, \textit{S believes p iff q} \not \models \textit{S wants q}\)

This feature of desire reports has been discussed by Villalta (2008), Rubinstein (2012), and Phillips-Brown (2018). For instance, Villalta observes that both (29a) and (29b) can be true while (29c) is false:

To see that this is possible, let wc, \(\overline{\textsc {w}}\) c, w\(\overline{\textsc {c}}\), and \(\overline{\textsc {w}}\overline{\textsc {c}}\) represent the propositions that Mary wins and physically collapses, that she doesn’t win but still collapses, etc. Consider some context where \({\mathcal {A}} = \{\) wc, \(\overline{\textsc {w}}\) c, w\(\overline{\textsc {c}}\), and \(\overline{\textsc {w}}\overline{\textsc {c}}\) \(\}\). Suppose further that Bill’s preferences over these alternatives are as follows:

\(\textsc {w}\overline{\textsc {c}}\) \(\succ _{\text {Bill}}\) wc \(\succ _{\text {Bill}}\) \(\overline{\textsc {w}}\overline{\textsc {c}}\) \(\succ _{\text {Bill}}\) \(\overline{\textsc {w}}\) c

Then (29a) and (29b) are true, but (29c) is false. Again, it is worth remarking that both (29a) and (29b) can be true without (29c) being defined. This could happen if, for instance, the alternatives are just w and \(\overline{\textsc {w}}\). Then (29c) will suffer from presupposition failure, since the proposition that Mary collapses physically won’t be represented. Presumably, this captures the felt infelicity of (29c) in many contexts.

So far, we have been concerned with failures of consequence, but there are also some interesting validities. For one thing, we have the following rule which Blumberg and Hawthorne (2021) call Want Weakening, after an analogous principle in deontic logic discussed by Cariani (2016):Footnote 39

Want Weakening

\(\textit{S wants p}, \textit{S wants q} \models \textit{S wants p or q}\)

The pattern exhibited by Want Weakening is highly plausible. However, it can be shown that several popular analyses of desire render it invalid.Footnote 40

Finally, we also have the following:Footnote 41

Acceptable Disjuncts

\(\textit{S wants p or q} \models \lnot (\textit{S wants} \ \lnot \textit{p})\)

Acceptable Disjuncts accounts for an observation by Crnič (2011, 166) to the effect that disjunctions in the scope of desire reports give rise to an “acceptability inference” regarding both disjuncts. That is, both disjuncts need to be judged to be acceptable, or OK, by the subject. For instance, neither (32a) nor (32b) are felicitous:Footnote 42

To sum up, the preference-based semantics for desire reports captures a fairly wide range of phenomena. Among other things, it accounts for why desire is neither upward nor downward monotonic (Stalnaker , 1984; Heim , 1992; Levinson , 2003; Lassiter , 2011), and why desire isn’t closed under believed equivalence (Villalta , 2008; Phillips-Brown , 2018). Moreover, although the theory allows for closure failures, it is not too weak, as it also validates some intuitively compelling principles. For instance, on this account \(\ulcorner \)S wants p or q\(\urcorner \) follows from \(\ulcorner \)S wants p\(\urcorner \) and \(\ulcorner \)S wants q\(\urcorner \), and it also explains why disjunctions in the scope of desire verbs give rise to an “acceptability inference” regarding both disjuncts (Crnič , 2011).Footnote 43 These successes are significant in themselves, but they gain even greater interest given that the proposal is independently motivated. The central features of the account of desire are shaped by the theory of preference from Sect. 2, and the intuitive connection between preference and desire. Overall, I think that this preference-based theory of want reports provides us with a promising approach to desiderative attitudes.

4 Possible worries

By way of a conclusion, I raise and respond to two concerns for the approach to preference and desire developed in Sects. 2–3. The first worry involves a detail in the logic of desire, namely non-monotonicity (Sect. 4.1). The second concern involves issues around how alternatives get fixed in context (Sect. 4.2).

4.1 Abominable conjunctions

In Sect. 3.2, I showed that desire reports are not closed under entailment on my account. For instance, I predict that there are contexts where (26a) is true but (26b) is false:

Now, von Fintel (1999, 120) raises a challenge for approaches to desire that reject upward monotonicity. The central observation is that conjunctions such as (33) are unacceptable:

But this is surprising if desire reports are non-monotonic: if (26a) is true and (26b) is false, then why can’t one felicitously conjoin them as in (33)? By contrast, this is easily explained on accounts that validate monotonicity—conjunctions such as (33) can never be true. Von Fintel takes this to be a compelling argument for thinking that desire is closed under entailment.Footnote 44

However, recent work on desiderative attitudes suggests that von Fintel’s argument fails to be decisive. For one thing, as Blumberg (2021) observes, it simply isn’t the case that conjunctions of the form \(\ulcorner \)S wants p but S doesn’t want q\(\urcorner \) are always unacceptable when p entails q. Consider the following scenario from Blumberg (2021, 3):

Prisoner: Ann thinks that there is exactly one prisoner in the dock. She also thinks that this individual is either Bill or Carol, and that the prisoner might be hanged. Bill is Ann’s mortal enemy, so it would be best for Ann if Bill is the prisoner and is hanged. By contrast, Carol is Ann’s friend, so even if Carol is the prisoner, Ann would hate it if she was hanged.

The prisoner is Bill and Bill hangs obviously entails The prisoner hangs. Yet the conjunction (34) is perfectly acceptable. Indeed, Ann herself could say ‘I want the prisoner to be Bill and for Bill to hang, but I don’t want the prisoner to be hanged (since the prisoner could be Carol)’. This would be difficult to explain if desire was monotonic.

Moreover, Blumberg and Hawthorne (2022) note that the pattern exhibited by (33) also arises with attitude verbs that are plausibly non-monotonic. For instance, they consider ‘fear’. Suppose that you’ve just lost your job. Because you have bills to pay, (35a) is true. But it doesn’t follow that either (35b-i) or (35b-ii) are:

This indicates that ‘fear’ is non-monotonic. Now consider the following scenario from Blumberg and Hawthorne (2021, 3):

Fortune: Three coins will be flipped, and Bill’s reckless brother has bet the family fortune on the outcome. If the first coin lands heads, and the second or third coin lands tails, the fortune will be doubled. Any other configuration of the coins leads to the fortune being lost.

(36) is easily heard as true in this scenario:

After all, if all three coins land heads, Bill knows that the fortune will be lost, and he would certainly not like that. But by the same token, (37) is also easily heard as false:

After all, if the first coin lands heads, there’s a good chance that the fortune will be doubled, and Bill would certainly like that. However, Blumberg and Hawthorne observe that infelicity results if we try to conjoin (36) with the negation of (37):

Intuitively, the unacceptability of (38) is related to the infelicity of (33). Assuming that ‘fear’ is non-monotonic, the unacceptability of (38) can’t be explained by appealing to monotonicity. But then it is plausible that the infelicity of (33) shouldn’t be explained by appealing to monotonicity either. A more general explanation is needed. To be clear, such an explanation still needs to be provided, so there is more work to be done here. But for our purposes, the important point is that conjunctions such as (33) don’t obviously tell against a non-monotonic analysis of desire reports.Footnote 45

4.2 Fixing alternatives

Another worry is that my account seems to make too many desire reports come out false.Footnote 46 Consider the following example:

Wine: We’re at a restaurant choosing what to drink with dinner. The menu lists several wines and beers. The best wines are better than anything else, but some of the beers are better than some of the mediocre wines. You ask me what I’d like to drink. I reply:

(39) is perfectly acceptable here. However, the account seems to predict that the report should be false, since there are some wine-entailing alternatives that are ranked below some \(\lnot \)wine-entailing alternatives.

This worry assumes that the background set of alternatives is relatively fine-grained, so that each specific wine and beer is represented. But it’s not obvious that this is the case. If a comparatively coarser-grained set of alternatives is in play, then the account can handle this example. For instance, suppose that the relevant set of alternatives is \({\mathcal {A}} = \{\textsc {w}, \overline{\textsc {w}} \}\), where w and \(\overline{\textsc {w}}\) are the propositions that I get wine with dinner, and that I don’t get wine with dinner, respectively. We can suppose that my preference ranking over these alternatives is as follows:

w \(\succ _{\text {Me}}\) \(\overline{\textsc {w}}\)

In this case, (39) is predicted to be true.Footnote 47

This response touches on a more general issue about how the background set of alternatives gets determined in context. This is obviously an important topic, and the account won’t be complete without a predictive theory of how this parameter gets fixed. Unfortunately, I don’t have a detailed answer at present, and I must leave the provision of such a theory for future work. That said, I’d like to register that there is independent motivation for thinking that desire reports exhibit a fair amount of “shiftness” in the alternatives relative to which they’re evaluated. To see this, consider (40) in the following scenario:

Envelopes: There are two red envelopes and one blue envelope. One of the red envelopes contains $100, while the other contains $10; the blue envelope contains $50. An envelope will be selected at random and given to you. You say:

(40) is easily heard as false here. For instance, it would be natural for someone to respond by saying something like ‘I’m confused, since obviously you don’t prefer getting the red envelope with $10 to getting the blue envelope. So, how could you be happy with getting a red envelope?’. On the other hand, the report can also be heard as true. This can be brought out if it is made salient that the expected value of getting a red envelope is greater than getting the blue envelope:

(40) is acceptable here. But nothing concerning the subject’s internal psychology changed between these two contexts. So, accounts that reduce the semantic value of desideratives to internal psychological features will have a hard time explaining the contrast. This supports alternative-sensitivity: we can explain the differences in how (40) is heard by appealing to shifts in which alternatives are relevant. In the first context, a relatively fine-grained set of alternatives is relevant, e.g. \({\mathcal {A}} = \{\textsc {r100}, \textsc {r10}, \textsc {blue}\}\), where r100 is the proposition that you get the red envelope with $100, r10 is the proposition that you get the red envelope with $10, and blue is the proposition that you get the blue envelope. By contrast, (40) is acceptable in the second context because a more coarse-grained set of alternatives is used, e.g. \({\mathcal {A}} = \{\textsc {r}, \overline{\textsc {r}}\}\), where r is the proposition that you get given a red envelope, and \(\overline{\textsc {r}}\) is the proposition that you get given a non-red, i.e. blue envelope. If alternative-sensitivity is the correct way to explain what is going on here, then charting the dynamics of alternative shift is a project that should be of fairly broad interest.Footnote 48

It is also worth emphasizing that no matter how exactly this meta-semantic question gets settled, it constitutes progress to say that the evaluation of preference claims and desire reports goes by a contextually determined set of alternatives. As we have seen, the semantic structures that I have posited allow us to explain the logical features of these constructions in a neat fashion. So, to a fairly large degree, the good-making features of the account don’t essentially hang on how exactly the set of alternatives gets fixed in context.Footnote 49\(^{,}\)Footnote 50

Notes

Influential earlier work includes (Heim , 1992; von Fintel , 1999; Levinson , 2003). More recent work includes (Villalta , 2008; Wrenn , 2010; Crnič , 2011; Lassiter , 2011; Rubinstein , 2012; Anand and Hacquard , 2013; Fara , 2013; Maier , 2015; Condoravdi and Lauer , 2016; Pearson , 2016; Drucker , 2017; Grano , 2017; Phillips-Brown , 2018; Blumberg , 2018; Blumberg and Holguín , 2019; Jerzak , 2019; Pasternak , 2019; Phillips-Brown , 2021; Blumberg and Hawthorne , 2022; Blumberg and Hawthorne , forthcoming; Blumberg , 2021; Blumberg , forthcoming).

Although comparative preference claims have received relatively little attention, their analogue in the domain of deontic modality, namely claims of comparative betterness, have been more closely examined (Goble , 1989; Goble , 1990b; Goble , 1990a; Goble , 1993; Lassiter , 2017; Gillies , 2021). I leave a careful comparison of desideratives with deontic constructions for a future occasion.

See, for example, Davis (1984) for an explicit discussion of this connection.

I assume that the arguments to ‘prefer’ denote propositions, which for simplicity I take to be sets of possible worlds. But I expect that the main ideas could be readily adapted to frameworks on which propositions are more fine-grained entities, or even to non-propositional approaches to the arguments to ‘prefer’.

See von Fintel (1999, 100) for a clear statement of this position. Von Fintel explicitly allows that factors distinct from monotonicity properties can play a role in licensing NPIs.

By ‘restrictedly downward monotonic, I mean ‘Strawson downward monotonic’. For more on Strawson entailment, see Sect. 2.3.

The literature on free choice is vast. See among others (Kamp , 1974; Kamp , 1978; Dayal , 1998; Zimmermann , 2000; Kratzer and Shimoyama , 2002; Asher and Bonevac , 2005; Geurts , 2005; Schulz , 2005; Simons , 2005; Alonso-Ovalle , 2006; Aloni , 2007; Fox , 2007; Klinedinst , 2007; Ciardelli et al. , 2009; Chemla , 2009; Barker , 2010; Franke , 2011; Aher , 2012; Chierchia , 2013; Dayal , 2013; Roelofsen , 2013; Charlow , 2015; Fusco , 2015; Starr , 2016; Willer , 2017; Romoli and Santorio , 2017; Aloni , 2018).

It is worth noting that such a project will also involve developing a semantics for preference reports. This is because theories of free choice assume a background semantics for the embedding operator (in this case ‘prefer’). What exactly the background preference semantics would have to look like partly depends on the chosen account of free choice. For instance, theorists have observed that the canonical free choice effect is limited to existential modals, and doesn’t arise in the same form with universal modals, e.g. deontic ‘must’: ‘You must take an apple or a pear’ doesn’t imply that you must take an apple and that you must take a pear. Accounts of free choice such as that of Aloni (2007) are tailored to capture this difference, and only generate free choice effects for operators whose semantics involves existential quantification. Thus, if Aloni’s theory of disjunction in modal contexts is used as a basis to try to explain (3b-ii), the background semantics for ‘prefer’ would need to be based on existential, rather than universal, quantification.

The same reviewer suggests that the perceived goodness of the inference from (3b-i) to (3b-ii) could be due to our willingness to reason from super-kinds to sub-kinds, rather than the monotonicity properties of preference reports, as we have claimed. More specifically, they argue that super-kind to sub-kind reasoning is driven by stereotypes (Sloman , 1998), and since prawns are plausibly a stereotypical type of seafood, this explains why we tend to accept (3b-ii) on the heels of (3b-i). But this explanation does not cover enough of the data. For one thing, the truth of (3b-i) licenses inferences that go well beyond those that involve stereotypical forms of seafood. If X is any type of seafood on the buffet table, then so long as X has been made salient, the truth of (3b-i) implies that you prefer X to chicken. For instance, if it is common ground that there is urchin on the table, (3b-i) implies ‘You prefer urchin to chicken’. (Think of how bewildered you’d be if I brought you a plate of chicken and said ‘I know you saw that there was urchin on the table, and I know you said that you prefer seafood to chicken, but I thought you’d prefer chicken to urchin’.) But we may assume that urchin isn’t a stereotypical type of seafood. For another, we can construct examples featuring categories for which the stereotypical/non-stereotypical distinction plausibly fails to apply. For example, suppose that you will be given some colored shapes from a box of various shapes of different colors. If you say ‘I prefer red shapes to blue shapes’, we easily hear this as meaning that you prefer any sort of red shape to any sort of blue shape. (You’d have a right to complain if I gave you two blue squares and said ‘I know you saw that there were red triangles in the box, and I know you said that you prefer red shapes to blue shapes, but I thought you’d prefer blue squares to red triangles’.) But it is fairly implausible that these inferences are driven by stereotypicality judgments, since it is unclear what constitutes a stereotypical red shape in context. Similar points apply to the examples (13) and (14) below.

I will often drop the world subscript on preference orderings when no confusion arises.

More formally: for any subject S, world w, modal base \({\mathcal {B}}\), and proposition p: best(p) = \(\{ w' \ \in \ {\mathcal {B}} \ \cap \ p \ | \ \lnot \exists w'' \ \in \ {\mathcal {B}} \ \cap \ p \ \text {such that} \ w'' >_{w, S} w' \}\). Goble (1993) introduces an analogous function when discussing best worlds accounts of deontic ‘better’.

Theorists have also analyzed desire using orderings over worlds in a different way from that considered above. These are accounts based on “comparative desirability”: the idea is that S desires p when S prefers the closest p-worlds to the closest \(\lnot p\)-worlds (Stalnaker , 1984; Heim , 1992). The most natural extensions of these theories to preference claims suffer from similar problems to those raised here: they wrongly predict that (17) should be false, and they make Downwardness 1 and Downwardness 2 straightforwardly invalid. Also see Goble (1989, 1990a, 1990b, 1993) for a similarity-based account of comparative betterness claims. I think that analogous concerns could be raised for Goble’s account, but I will not pursue this line of criticism here.

\(EV_{w,S}(p) = \sum _{w' \in W}u_{w,S}(w')\cdot Cr_{w,S}(w'|p)\), where \(Cr_{w,S}\) represents S’s credences over the live possibilities in w, and \(u_{w,S}\) is an evaluation function, i.e. a function from W (the set of all worlds) to the real numbers.

See Goble (1996) for an analogous decision-theoretic account of comparative betterness claims.

One might want to allow the set of alternatives to vary from world to world. One could capture this by maintaining that interpretation proceeds relative to a function from worlds to sets of alternatives, rather than just a set of alternatives. But we’ll ignore this complication in what follows.

The idea that expressions of bouletic states in natural language should be evaluated relative to a set of alternatives goes back at least to Villalta (2008). Also see Phillips-Brown (2018), Blumberg and Hawthorne (2022, forthcoming) for more recent developments, as well as the discussion in fn.43.

Similar questions arise for the alternative-sensitive accounts of desire verbs mentioned in fn.19. I am sympathetic to the treatment of these issues in Blumberg and Hawthorne (2022, forthcoming). The discussion below and in Sect. 4.2 mirrors some of the arguments in these papers.

Cf. Cariani’s (2013) notion of a proposition being “visible” with respect to a background partition of logical space. This notion of representation is also put to use in Blumberg and Hawthorne (2021, forthcoming).

Strawson validity has been used to account for a range of natural language phenomena (see von Fintel, 1999; Cariani and Goldstein, 2018; Mandelkern, 2020. That said, one can raise questions about how exactly the notion of Strawson validity bears on intuitions about natural language inferences. For instance, Strawson entailment fails to be transitive (Dorr and Hawthorne , 2018). I’m sympathetic to these concerns, but I don’t think that they should trouble us here. For one thing, our use of Strawson validity is fairly constrained, since we’re mostly only interested in entailments from a single sentence schema. Moreover, the relevant definedness conditions that I propose for preference claims and desire reports essentially only serve to check that the space of alternatives is sufficiently well behaved. In most cases of interest, it is fair to assume that these presuppositions will be met (also see the discussion in Sect. 3.2).

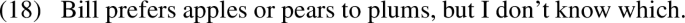

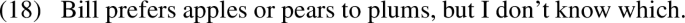

Some might worry about examples such as (18):

(18) is acceptable, but my account seems to predict that it should be incoherent, since the first conjunct should entail ‘Bill prefers apples to plums and Bill prefers pears to plums’ on a natural choice of alternatives. However, in this example I suggest that ‘or’ takes wide-scope with respect to the preference claim, and means the following:

It is worth noting that proponents of semantic accounts of free choice effects under possibility modals also appeal to wide-scope disjunction in response to similar examples (Simons , 2005; Aloni , 2007). See Fusco (2019) for a recent defense of this move.

For this proof sketch and the ones that follow, I assume that the sentential connectives are interpreted as standard Boolean functions, modulo presuppositions. Moreover, I assume that undefinedness obeys a weak Kleene logic in the metalanguage (Gamut , 1990). Essentially, this all means that if presuppositions are satisfied, then we proceed exactly as we would in a classical setting.

Suppose \(\ulcorner \lnot \)S prefers p to p\(\urcorner \) is defined. Then there must be some p-entailing alternative A. Since \(\succ _{S}\) is irreflexive, we have \(A \not \succ _{S} A\). Thus, \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to p\(\urcorner \) can’t be true, and so \(\ulcorner \lnot \)S prefers p to p\(\urcorner \) is true.

See, for example, Fishburn (1970) for the importance of transitivity and asymmetry to capture our intuitive notions of preference. Similarly, Goble (1989, 299) says that these properties are ‘generally regarded as a sine qua non of a notion of relative betterness’. As with Irreflexivity, Transitivity and Asymmetry flow from the transitivity and asymmetry of \(\succ \).

I take the “Weakening” name from a principle for desire verbs discussed by Blumberg and Hawthorne (2021)—see Sect. 3.2. Analogues of the Preference Weakening principles for comparative betterness claims are discussed by Goble (1989). For a proof of Preference Weakening 1, suppose \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is true, \(\ulcorner \)S prefers r to q\(\urcorner \) is true, and \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p or r to q\(\urcorner \) is defined. First, note that any \(p \vee r\)-entailing alternative A either entails p or entails r. For suppose not. Then A must contain both \(\lnot p\)-worlds and \(\lnot r\)-worlds along with p-worlds and r-worlds. But then neither p nor r can be represented. Now let A be any p-entailing alternative. Let B be any q-entailing alternative. Since \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is true, we must have \(A \succ _{S} B\). A similar argument shows that \(A \succ _{S} B\) if A is a r-entailing alternative. Since every \(p \vee r\)-entailing alternative entails p or entails r, and B was arbitrary, \(\ulcorner \)S prefers p or r to q\(\urcorner \) is true. A similar argument establishes the validity of Preference Weakening 2.

Preference Weakening should be sharply distinguished from principles such as the following: \(\textit{S prefers p to q}, \textit{S prefers r to s} \models \textit{S prefers p or r to q or s}\). Such principles are not valid on this semantics. This is as it should be: ‘You prefer prawns to chicken’ and ‘You prefer chicken to lobster’ can both be true without ‘You prefer prawns or chicken to chicken or lobster’ being true, since the latter suggests that you prefer chicken to itself.

Thanks to Sam Carter and Matt Mandelkern for helpful discussion of the issues discussed here.

For a further example, Preference-to-Indifference in conjunction with my semantics for ‘prefer’ implies that ‘You are indifferent between winning $100 or losing $100 and winning $50’ should be true on the natural choice of alternatives, which doesn’t seem quite right.

There are weaker semantics for indifference claims that also secure Indifference-to-Preference while still invalidating Preference-to-Indifference. A chain \(\Delta \) in a partially ordered set \(\Gamma \) is a totally ordered subset of \(\Gamma \). A maximal chain \(\Delta \) in a partially ordered set \(\Gamma \) is a chain in \(\Gamma \) such that if \(\Delta \subsetneq \Omega \subseteq \Gamma \), then \(\Omega \) is not a chain in \(\Gamma \). Then we could require for the truth of \(\ulcorner \)S is indifferent between p and q\(\urcorner \) that there be some maximal chain \({\mathcal {C}}_{1}\subseteq {\mathcal {A}}\) containing a p-entailing alternative that outranks any q-entailing alternative in \({\mathcal {C}}_{1}\); and there be some maximal chain \({\mathcal {C}}_{2}\subseteq {\mathcal {A}}\) containing a q-entailing alternative that outranks any p-entailing alternative in \({\mathcal {C}}_{2}\). (It can be checked that the entry for ‘indifferent’ in the main text is an instance of this semantics with the additional requirement that no maximal chain can contain both p-entailing and q-entailing alternatives.) I leave the exploration of such variant semantics for future research.

It is also plausible that ‘disprefer’ doesn’t merely express a lack of preference. For example, ‘You disprefer chicken to seafood’ doesn’t seem true in the seafood example (likewise, ‘You disprefer winning $100 or losing $100 to winning $50’ doesn’t seem true). A natural entry for ‘disprefer’ is the following:

Alternative-sensitive semantics for disprefer

\(\ulcorner \)S disprefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is defined relative to \(\langle w, {\mathcal {A}}, {\mathcal {O}} \rangle \) only if

both p and q are non-trivially represented by \({\mathcal {A}}\)

If defined, \(\ulcorner \)S disprefers p to q\(\urcorner \) is true relative to \(\langle w, {\mathcal {A}}, {\mathcal {O}} \rangle \) iff

for every \(B \in {\mathcal {A}}\) such that \(B \subseteq p\), and every \(C \in {\mathcal {A}}\) such that \(C \subseteq q\): \(C \succ _{w, S} B\)

To be clear, the claim we are exploring is that ‘prefer’ and ‘want’ have a similar semantics. I do not intend to argue for the stronger thesis that the meaning of ‘want’ is somehow built from the meaning of ‘prefer’, or that the latter is linguistically or psychologically prior to the former, e.g. in terms of morphology or acquisition. Thanks to a reviewer for helpful discussion here.

See Grano and Phillips-Brown (2020) for extensive discussion of this point.

See Blumberg and Hawthorne (2022) for an analysis of hope reports as well as a more detailed discussion of the doxastic constraints imposed by these ascriptions.

The proof of Want Weakening is similar to the proof of Preference Weakening 1 given in fn.27.

For instance, Blumberg and Hawthorne (2021) show that Levinson’s (2003) decision-theoretic analysis invalidates the principle (their countermodel is inspired by a similar countermodel provided by Cariani (2016) against certain decision-theoretic analyses of deontic modals.) It can also be shown that Heim’s (1992) account based on comparative desirability also fails to validate the inference.

Suppose \(\ulcorner \)S wants p or q\(\urcorner \) is true, and \(\ulcorner \lnot \)(S wants \(\lnot \)p)\(\urcorner \) is defined. Note that there must be both \(\lnot p \wedge \lnot q\)-entailing alternatives and p-entailing alternatives. Let A be an arbitrary \(\lnot p \wedge \lnot q\)-entailing alternative, and let B be an arbitrary p-entailing alternative. Then we must have \(B \succ _{S} A\), and so \(A \not \succ _{S} B\). But A entails \(\lnot p\), and so \(\ulcorner \lnot \)(S wants \(\lnot \)p)\(\urcorner \) is true.

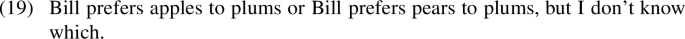

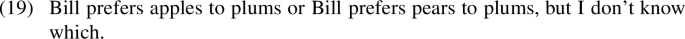

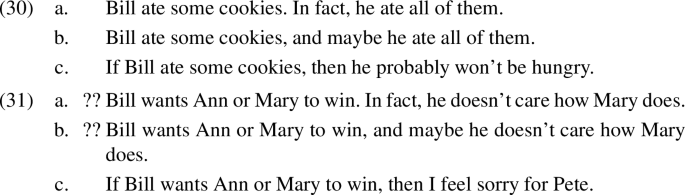

Crnič tries to capture this effect by maintaining that it is a type of implicature. However, the phenomenon doesn’t pattern with canonical implicatures. Consider, for instance, the non-exhaustivity inference triggered by ‘some’. It is plausible that this inference arises as an implicature in part because the relevant effect is optional. For example, in (30a) it is canceled, in (30b) it is suspended, and (30c) shows that it doesn’t survive being embedded. By contrast, it’s quite difficult to interpret (31a) and (31b). And the requirement that both Ann winning and Mary winning are highly preferred by Bill survives being embedded in a conditional, as (31c) illustrates. (These contrasts echo a similar argument by Cariani (2013) against pragmatic accounts of Ross’s Puzzle in the deontic domain.)

No existing analysis of desire that I’m aware of—apart from the one developed here—captures all of the effects discussed above. For instance, the popular best worlds semantics of von Fintel (1999) predicts that desire should be closed under entailment, and it predicts that desire should be closed under believed equivalence. It also fails to validate Acceptable Disjuncts. As for the decision-theoretic analysis of Levinson (2003), this theory also predicts that desire should be closed under believed equivalence, it renders Acceptable Disjuncts invalid, and as discussed in fn.40, it fails to validate Want Weakening. Heim’s (1992) account based on comparative desirability suffers from the same problems. What is more, it can be shown that many existing alternative-sensitive accounts of desire, namely the analyses of Villalta (2008), Lassiter (2011), and Phillips-Brown (2018) do not explain the phenomena. For instance, Lassiter’s entry fails to validate Want Weakening, and Phillips-Brown’s account makes desire closed under entailment.

Some might worry that my claims in this section are in tension with some of the arguments in Sect. 2.1, since there I used considerations from abominable conjunctions for preference (e.g. (4a) ‘You prefer seafood to chicken, but you don’t prefer prawns to chicken’) to support the validity of Downwardness. However, I also provided other reasons in favor of Downwardness, e.g. the fact that preference claims with entailing arguments are unacceptable. Also, the point here is not that considerations from abominable conjunctions never provide insight into the logical properties of the target operator, but rather that these data are not necessarily decisive.

Thanks to Milo Phillips-Brown for helpful discussion of the arguments in this section.

Note that the Wine case is in some ways similar to the Insurance case from Sect. 2.2.1. In the latter scenario, the alternatives relative to which (17) (‘Sue prefers buying insurance to not buying insurance’) is evaluated are just buying insurance and not buying insurance, even though the possible outcomes are more fine-grained, e.g. Sue could fail to buy insurance and there be no fire.

Also see Phillips-Brown (2022) for further arguments to the effect that desire reports exhibit various dimensions of context sensitivity, one of which is tied to the background set of alternatives in play.

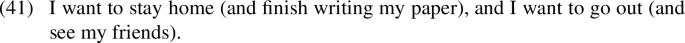

A reviewer argues that cases of conflicting desires such as (41) pose a problem for the analysis: