Abstract

Context

There is concern that urbanization threatens bees, a diverse group of economic importance. The impact of urbanization on bees is likely mediated by their phenotypic traits.

Objectives

We examine how urban cover and resource availability at local and landscape scales influences both species taxonomic and functional diversity in bees.

Methods

We used a combination of aerial netting and pan traps across six sampling periods to collect wild bees in 18 urban gardens spanning more than 125 km of the California central coast. We identified 3537 specimens to genus and, when possible, to species to obtain species richness and abundance at each site. For each species we measured a suite of bee traits, including body size, sociality, nesting location, nesting behavior, pollen-carrying structure, parasitism, and lecty.

Results

We found that increased garden size was positively associated with bee species richness and abundance. Somewhat counterintuitively, we found that urban cover surrounding gardens (2 km) was positively associated with bee species richness. Urban cover was also associated with the prevalence of certain bee traits, such as bees that excavate nests over those who rent, and bees with non-corbiculate structures. We suggest that urban habitats such as gardens can host a high number of bee species, but urbanization selects for species with specific traits.

Conclusions

These findings illustrate that local and landscape features both influence bee abundance, species richness, and the frequency of specific traits. We highlight the importance of trait-based approaches for assessing biodiversity in urban landscapes, and suggest conceptualizing urbanization as a process of habitat change rather than habitat loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Functional diversity can be used to infer how environmental stressors influence complex ecosystem processes (Laakso and Setälä 1999; Norberg et al. 2001; Cadotte et al. 2011). Functional diversity refers to traits, the components of an organism’s phenotype that are important for an ecosystem-level process (Tilman 2001; Petchey and Gaston 2006). Trait-based metrics of community functional structure include, for example, feeding types, habitat preferences, body size, and dispersal ability. Trait-based metrics may be more important than species taxonomic identity for predicting ecological processes (Petchey and Gaston 2006). For example, in insect pollinator guilds, traits related to sociality and nesting behaviors may be more critical than species identity for predicting responses to environmental disturbance (Winfree et al. 2009; Williams et al. 2010).

The composition of functional traits in a community may mediate the impact of habitat loss on species persistence (Bommarco et al. 2010; Maire et al. 2012; Tscharntke et al. 2012). Local features, such as resource availability, and landscape features, such as natural habitat availability or regional climate, may filter which species are present because they possess traits suitable for a given habitat (Keddy 1992; Diaz et al. 1998) or because species exhibit variation in life history strategies and tolerance to stress (e.g., Waser et al. 1996; Hulot et al. 2000). This is seen across multiple taxa, including bacteria (e.g., Langenheder and Prosser 2008), algae (e.g., Fowler-Walker et al. 2006), plants (e.g., Lavorel et al. 2007), and insects (e.g. Philpott et al. 2019) and birds (e.g., Tscharntke et al. 2008; Clough et al. 2009). For example, larger-bodied species may be more likely to decline than small-bodied species (Bartomeus et al. 2013) or more tolerant to the loss of resources than small-bodied species due to dispersal ability (Bommarco et al. 2010; Öckinger et al. 2010). Feeding generalists may be more resilient to fluctuations in resource availability than specialists with narrow diets (Root 1973; Kassen 2002; Rand et al. 2006), and social species may be more adaptive to environmental stress than solitary species due to risk spreading among group members (Gadagkar 1990; Hoiss et al. 2012).

Bees (Superfamily: Apoidea) are a species-rich group of mobile insects threatened by habitat loss (Potts et al. 2010; Goulson et al. 2015). While bee taxonomic (Klein et al. 2003; Gomez et al. 2007) and functional (Hoehn et al. 2008; Blüthgen and Klein 2011) diversity are both tied to the delivery of pollination, trait and taxonomic diversity may respond differently to land-use (Murray et al. 2009; Roulston and Goodell 2011; Hoiss et al. 2012). For example, bees who forage further may be able to persist in fragmented landscapes (Gathmann and Tscharntke 2002; Bommarco et al. 2010; Härtel and Steffan-Dewenter 2014; Redhead et al. 2016), but they may also be exposed to agrochemicals and pollutants (Hladik et al. 2016; Long and Krupke 2016). Higher reproductive capacity may buffer bee losses against disturbances (De Palma et al. 2015; Persson et al. 2015), or result in greater resource requirements (Schmid-Hempel and Durrer 1991; Woodard and Jha 2017). To date, investigations into how environmental landscapes structure bee functional diversity have focused on bee communities in natural or agricultural systems (e.g., Hoiss et al. 2012; Kennedy et al. 2013). We know less about bee functional diversity in urban systems (but see Martins et al. 2017; Normandin et al. 2017; Bulchholz et al. 2020).

Urbanization—the conversion of natural habitat into impervious land cover—often drives biotic homogenization, wherein a few species with competitive traits become dominant while many native species are lost (McKinney 2006). Urbanization impacts bee species richness and abundance, often due to losses of floral or nesting resources at local and landscape scales (e.g., Fischer et al. 2016; Ballare et al. 2019; Guenat et al. 2019). These local and landscape features may filter which bee traits are dominant within the community (Hung et al. 2019; Buchholz et al. 2020). For example, habitat and feeding specialists across multiple insect taxa often respond negatively to urbanization (Threlfall et al. 2015; Knop 2016), while generalist responses are highly variable (Burkman and Gardiner 2014). It is less clear if these generalizations apply to urban bees. Urbanization may also affect the relative representation of bee species characterized by their nesting behavior; Cane et al. (2006) found that ground-nesting specialists were underrepresented and less abundant than cavity-nesting species in smaller urban habitat fragments, and Quistberg et al. (2016) found that mulch cover in urban gardens is associated with fewer ground-nesting bees. Landscape-level features around urban sites are also important if remnant and restored habitat provide resources for species with particular traits (Buchholz et al. 2020).

Within cities, gardens are increasingly planted to support pollinators. Urban gardens may harbor high levels of bee trait diversity in comparison to other urban habitat types such as parks and cemeteries (Normandin et al. 2017). In this study, we evaluate and compare how local and landscape features influence bee taxonomic diversity and functional traits in community gardens spanning more than 125 km of central California, with the goal of understanding how gardens can be managed to support bees. We ask if bee richness, bee abundance, and functional traits of bees vary with local garden management and landscape features.

Methods

Study system

The study took place in 18 urban community gardens in the California central coast in Monterey, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz counties (Fig. 1). The gardens are surrounded by natural, agricultural, and urban land cover, reflecting a gradient in landscape diversity and intensity. The gardens are > 2 km apart in proximity from one another, have been in cultivation for 5 to 47 years, and are 444 to 15,525 m2 in size.

Bee surveys

We collected bees in each garden during summer 2015 using aerial netting and pan trapping methods. Sampling occurred over 5 periods between mid-June and mid-September 2015 (approximately every 3 weeks). We aerial netted within a 20 × 20 m plot placed at the center of each garden for 30 min. We also pan trapped using elevated color pan traps (yellow, white, and blue). Traps were mounted atop 1.2 m tall PVC pipes and the pan bowls were filled with a water and 1.5% soap solution. On sampling days, we positioned traps (one yellow, one white, one blue) in a triangular formation, 5 m apart within the 20 × 20 m survey plot. Traps were left for a total of 9–11 h, set out at 8–9 AM and collected the same day between 5 and 7 PM. We identified bees using online resources, image databases, books, and dichotomous keys (see Online Appendix A for full list and citations). We identified bees to species (or morphotaxon for certain genera such as Lasioglossum (Dialictus) where species identification is difficult). Identifications were verified by researchers trained in bee identification according to Michener et al. (1994) at the 2014 Bee Course (American Museum of Natural History).

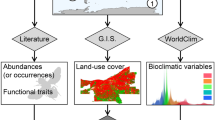

Trait data

We selected six bee traits recognized for their functional role in bee assemblages (Violle et al. 2007; Williams et al. 2010): body size, sociality, feeding behavior, nesting location, nesting behavior, and pollen-carrying structure (Tables 1, 2). We refer to these as ‘functional traits.’ We searched the literature (see Online Appendix A, Table S1) to determine which attributes each species exhibits in terms of sociality (solitary, social), feeding behavior (polylectic, oligolectic, variable), nesting location (above ground, below ground, both), nesting behavior (excavate, rent), and pollen-carrying structure (scopa on leg, scopa on abdomen, corbicula, crop). For social behavior, we grouped solitary, sub-social, and communal species as “solitary,” and advanced eusocial and primitively eusocial species as “social.” For parasitic species, we categorized their sociality as “parasitic,” pollen-carrying structure as “no structure,” their nesting location as the location of their host species, nesting behavior as “NA.” We used bee identification guides and peer-reviewed literature for references (see Online Appendix A: Table 1). We then measured intertegular distance (ITD), a proxy for body size (Cane 1987). We randomly selected ten female individuals from each species, then used a microscope that captured an image of each specimen and Leica software to measure ITD (mm). When ten individuals were not available, we used the number of individuals available (from two to ten). We calculated the mean value of these measurements to assign to all individuals from these species.

Local and landscape features

We surveyed garden habitat characteristics at each period within a 20 × 20 m plot at the center of each garden. We counted and identified all trees and shrubs, and noted whether they were in flower. Then, in four, randomly placed, 1 × 1 m quadrants within the plot, we measured the height of the tallest herbaceous vegetation, identified all herbaceous plants and classified them as crops, ornamental plants or weeds, counted all flowers and the number of species in flower, and estimated the percent ground cover from mulch, bare soil, herbaceous plants, and leaf litter. We also measured the size of each garden. We averaged values collected over the sample periods for each habitat measurement for each garden. For landscape features, we used the 2016 National Land Cover Database (NLCD, Homer et al. 2020) in ArcGIS to calculate the proportion of urban, agricultural, and natural land use cover within (2 km) buffers surrounding each garden—a scale at which bees respond to landscape scale features in our system (Egerer et al. 2017) and in others (Kremen et al. 2004).

Analysis

We tested the response of bee abundance and richness to local and landscape features. We then evaluated the role of these features on functional diversity. Because many local and landscape features were correlated, we prioritized including those previously found to be important in describing pollinator diversity in these gardens (Quistberg et al. 2016; Plascencia and Philpott 2017). We identified collinearity of features in our models by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each variable using the car package (Fox et al. 2018) in R (R Core Team 2020). We used a cutoff score of 3 and removed the predictor features with the highest value in a stepwise approach until all features received a score below the cutoff. Our models included the response variables: garden size (acres), the number of flower individuals, the number of trees and shrub individuals, proportion bare soil, the number of herbaceous plant species (richness of crops, weeds, and ornamentals), and urban cover within 2 km. We additionally calculated Pearson’s correlations for these variables (Online Appendix A, Table S2) and tested for collinearity between bee abundance and bee richness using the Hmisc package (Harrell and Dupont 2019). We included site as a random effect. To model total bee abundance, we fit a negative binomial error model to account for overdispersion. To model richness, we fit a Gaussian error model.

We fit linear and generalized linear mixed models (LMM and GLMM, respectively) to determine which local and landscape features influence bee richness and abundance. Our response variables were total bee abundance at each site at each sampling period and total bee richness at each site at each sampling period, calculated by merging pan trap data and aerial net observations. We included all specimens identified to species and morphotype. We used a model selection framework using the MuMln package (Barton 2018) and averaged the top models within two AICc points of the top model. Our approach averages a set of coefficients that are conditional on a specific set of covariates (Cade 2015; Banner and Higgs 2017). While we ensured little correlation between variables, it is controversial if averaging approaches should be used in cases where there is any multicollinearity between variables as this can lead to spurious results (Gunst 1983; Walker 2017). We used standard model assessment techniques to determine whether the final model met all the assumptions of a GLMM/LMM. To compute the unconditional variance, we used the method proposed by Burnham and Anderson (2004), as implemented in MuMIn. To determine the goodness-of-fit of the best models, we calculated a conditional pseudo-R2 value using the r.squareGLMM function.

We used the combined fourth corner and RLQ modelling approach in the ade4 package (Dray and Dufour 2007) in R to determine which local and landscape features of urban gardens filter bee traits. The RLQ method summarizes the joint relationships between local and landscape features (R matrix), bee species distribution among gardens (L matrix), and bee traits (Q matrix). The fourth corner approach tests for direct correlations between local and landscape features and bee traits (Dray and Legendre 2008; Dray et al. 2014). For the analysis, we removed singleton species and morpohotypes, as well as morphotypes that were missing trait data (those not identified to species) from the species abundance matrix (L) (19 species removed from trait analyses, 142 individuals). We included the same local and landscape features as in the analyses above. Following Dray et al. (2014), we first performed the RLQ method that consisted of a correspondence analysis on the species (L) matrix and principal component analysis on the R and Q matrices and used permutation models to evaluate (a) if garden features influence the distribution of bee traits (“model 2”), and (b) if traits influence the composition of species assemblages in relation to the local and landscape features (“model 4”). We visualized the RLQ results using a biplot to assess the global relationships between bee traits and local and landscape features. Second, we used the fourth corner analysis to determine the significance of each bee trait-factor relationship. For the analyses, we used Monte-Carlo permutations (n = 999) to test for correlations between quantitative variables and used the ‘D2’ correlation coefficient at a 0.95 level of significance to test for associations between quantitative variables and each categorical variable separately (Dray et al. 2014).

Results

Local and landscape features and bee richness and abundance

We documented 3537 individuals from 59 species and morphotypes of bees representing various traits (Table 1). The five most common bees recorded (74.2% all individuals) included honey bees (Apis mellifera), sweat bees (Halictus tripartitus and Lasioglossum (Dialictus) sp.), and bumble bees (Bombus vosnesenskii and Bombus caliginosus). 28.8% of species or morphotypes were rare and were recorded only once across sites. These include species with abdominal scopa (e.g., five species in Megachile) but also cleptoparasitic bees (Holcopasites sp.), mining bees (Andrena sp.), and others.

We found that both local and landscape features predicted bee species abundance, richness and traits in gardens. Bee abundance was significantly associated with garden size (Fig. 2) and marginally associated with urban cover (2 km), where larger gardens had more bee individuals (p < 0.05) and gardens surrounded by more urban cover had fewer individuals (p = 0.056). Bee richness was significantly associated with the number of flowers, garden size, and urban cover (2 km). Larger gardens (p < 0.01) and gardens surrounded by more urban cover (p < 0.01) had more bee species (p < 0.01), and gardens with more bare soil (p < 0.05) and more flowers (p < 0.001) had fewer species (Table 3 for test statistics for each model) (Fig. 3).

The variables significantly associated with wild bee richness. Garden size (acres) and urban cover (2 km) were positively related to richness. The number of flowers was negatively related to richness. The black line indicates the slope estimate and the gray is the 95% confidence interval around the estimate. Points represent wild bee abundance at a site at each survey period

Local and landscape features and bee traits

The gardens supported bees with a diverse range of body sizes, social behaviors, nesting locations, pollen-carrying structures, lecty, and parasitic behaviors (Tables 1, 2). The fourth corner test for bivariate relationships between traits and local and landscape factors found that below ground nesting, excavating, and legs with scopa were more positively associated with sites surrounded by more urban cover within 2 km, while above ground nesting, renting, and corbicula were negatively associated with urban cover (all relationships p < 0.05, Fig. 4a).

Results of the fourth-corner analysis and a combined fourth corner and RLQ analysis illustrate associations between local and landscape features and bee traits. Colored squares indicate significant associations (p < 0.05), where red indicates a positive and blue is a negative association. Grey is a nonsignificant association. Panel A shows a correlation table of bivariate associations between each trait with each factor. Panel B shows the correlation table between the RLQ axes and bee traits. Panel C shows which local and landscape features are associated with each RLQ axis

The combined RLQ and fourth-corner analysis revealed that, overall, local and landscape features did not influence the distribution of bee species (Model 2, P2 = 0.141) and bee traits did not influence the composition of species found in sites with certain local and landscape features (Model 4, P4 = 0.319). However, individual features were still significantly related to changes in certain bee traits. The first trait axis was driven by differences in the number of flowers (p < 0.05), where gardens with fewer flowers had fewer species exhibiting above-ground nesting, renting, and corbicula, and more species exhibiting below-ground nesting, excavating, and scopa on legs. The second trait axis was driven by urban cover (p < 0.01), where gardens surrounded by more urban cover were negatively associated with social bees and positively associated with solitary behavior and pollen transport in the crop (Fig. 4b, c).

Discussion

Local and landscape features and bee richness and abundance

Our study adds to the growing evidence that urban environments can support bee species (Matteson et al. 2008; Verboven et al. 2012), and that bee richness, abundance, and traits are driven by local and landscape features of the urban environment. In this system, percent urbanization ranged from 7.85 to 93.15% and we found that gardens surrounded by more urban land cover supported a higher richness of bee species. This is possibly because the urban landscape in this region is a mosaic of suburban and non-industrial areas such as gardens, parks, and semi-natural habitat that can serve as refugia and resources for a diverse assemblage of species within the urban matrix (Hall et al. 2017). Alternatively, gardens may act as resource-rich islands within an inhospitable habitat, attracting species who have nowhere else to go. Interestingly, we found that bee abundance declined with more urban cover, echoing the findings of similar studies (Fortel et al. 2014). In other words, while the urban environment supported a high diversity of bees, their abundance was low. If the urban matrix indeed includes diverse resources for pollinators, one speculative explanation is that gardens may not attract large numbers of bees from nearby home gardens and parks, which have been found to host an abundance of bees (Lowenstein et al. 2014; Hülsmann et al. 2015). These findings suggest that urbanization should be conceptualized as a process of habitat change, rather than habitat loss, with implications for the distribution of biodiversity.

In this system, urban cover was negatively co-linear with tree and shrub abundance, and therefore the positive impact of urban cover on bee richness may indicate that tree and shrub abundance had a negative impact on bee richness. This was unexpected, as was the finding that the number of flowers was negatively associated with bee richness. We suggest that increases to floral abundance and tree and shrub abundance in the gardens are associated with a dilution effect. Dilution has previously been observed for pollinators visiting sites with increase floral resources, especially in sites with high landscape diversity (Sha and Vandermeer 2009; Riedinger et al. 2014; Wenninger et al. 2016). This finding further builds the case against the assumption that all urban landscapes are bereft of resources for pollinators, and we propose that future studies in this region employ detailed, fine-scale assessments of urban landscape-level features. An alternative explanation is that an increased abundance of flowers may have not attracted bee species if they were the “wrong” type. It is well established that pollinator preference plays a role in community assembly. Because bees have preferences for certain plant groups (e.g., Asteraceae, Lamiaceae), flower identity and composition are important for shaping bee communities in urban gardens (Frankie et al. 2005), even more so than floral abundance (Lowenstein et al. 2019). Furthermore, although it is often assumed that native plants promote bee species in gardens, this has not been found previously in this system (Egerer et al. 2020), where the average native plant richness across gardens is 24.4% of all plants cultivated and ranges from 0 to 100%. In other systems, native plants may (Pardee and Philpott 2014) or may not (Matteson and Langelloto 2011) influence bee community composition. We therefore suggest that more research on plant preference is critical for promoting urban pollinators.

The only local factor important for both bee richness and abundance was garden size. Larger gardens supported both greater bee richness and greater abundance. Our observation supports previous research on the importance of habitat patch size for promoting bee diversity in agricultural and natural systems (Steffan-Dewenter 2003; Krauss et al. 2009; Hopfenmüller et al. 2020). Moreover, our findings are similar to other urban bee studies showing a positive effect of garden size on bees (Frankie et al. 2005; Cane et al. 2006; Matteson and Langellotto 2011; Pardee and Philpott 2014; Quistberg et al. 2016). However, some studies have found no effect of garden size on bees (Potter and LeBuhn 2015; Lanner et al. 2019). Garden size is likely associated with a greater number and diversity of resources for bees that could impact richness and abundance, though this may be region-dependent.

Local and landscape features and bee traits

While habitat change is often associated with colonization by generalist species across multiple systems (Rand and Tscharntke 2007; Rocha and Fellowes 2020), we did not find an association between lecty and urbanization or between lecty and any other factor we measured. Bee diet breadth can explain sensitivity to land use changes in agricultural (Steffan-Dewenter et al. 2006; Moretti et al. 2009), natural systems (Hopfenmüller et al. 2014), and urban systems (Fetridge et al. 2008; Banaszak-Cibicka and Żmihorski 2012), yet our results do not support any generalizations between diet and urbanization. We did find a link between urbanization and sociality—urban land cover supported more solitary bees than social bees. It has been observed that bees exhibiting social traits may be more impacted by disturbances (Winfree et al. 2009) and isolation from natural habitat (Williams et al. 2010). For example, Wilson and Jamieson (2019) found that social Bombus and Lasioglossum were negatively affected by urbanization, though other work has found either positive or no association between urbanization and social behaviors (Carper et al. 2014; Guenat et al. 2019). One possible explanation is that species that exhibit solitary behaviors may able to utilize urban environments in ways that social bees cannot and in ways not captured by our trait measurements.

Bees with scopa were positively associated with urban land cover. This finding is possibly driven by bees in the genus Halictus, which are a highly abundant group in our garden sites that feature scopa and are known to tolerate and utilize a wide range of floral resources (Cane 2015). Finally, like Buchholz et al. (2020), we found that urbanization was associated with nesting behavior and location, with gardens surrounded by more urban cover associated with below ground nesting species and excavators. This could be because these gardens provide the necessary soil substrate that is otherwise limited in highly urbanized areas with greater impervious land cover. Nesting location has previously been associated with responses to isolation from natural habitat, where species that nest above ground were most sensitive to habitat loss than below ground species (Williams et al. 2010). Clearly, more work is needed to make strong generalizations about the impact of urbanization, but this study suggests that urbanization is a strong determinant of trait composition in urban gardens.

We observed that local floral resources were negatively associated with solitary bee traits and with bees that carry pollen internally in their crop (a specialized behavior specific to bees such as those in the genus Hylaeus). This is surprising, because it is often assumed by conservation initiatives that flowers promote a variety of wild bees with different traits. But this study shows that not all bees benefit universally from increased floral abundance in gardens. However, our finding may be biased because we did not observe many social bee species, and the most abundant social species in our system was the honey bee (Apis mellifera), a generalist known to utilize a very wide range of plant species and that has been hypothesized to outcompete native species (Steffan-Dewenter and Tscharntke 2000). Indeed, the abundance of honey bees has previously been negatively correlated with wild bee species richness in our study sites (Plascencia and Philpott 2017). In urban gardens, Threlfall et al. (2015) found that the presence of exotic, non-native plants had a positive impact on honey bees, but not wild bees, suggesting that there is an interaction between floral identity and the prevalence of social insects in the garden that our study could not pinpoint. More research is needed on which floral types support a diverse assemblage of pollinators (see Rollings and Goulson 2019).

We expected to find a relationship between body size and local or landscape features because body size is directly related to foraging range (Greenleaf et al. 2007). Other urban bee studies have shown that urbanization filters for smaller bees (Hamblin et al. 2017), potentially due to heat island effects (Eggenberger et al. 2019), where larger bodied bees are more vulnerable to overheating than smaller species. We suggest that body size does not consistently respond to urban landscape-scale fragmentation, as some studies have found that small‐bodied bees are more sensitive (e.g., Cane et al. 2006) while other studies have concluded that small‐bodied bees respond positively to urbanization (e.g., Wray et al 2014). We expect that this variability reflects the fact that cities vary widely across regions. There may also be a trade‐off between the ability to access widely distributed resources and the ability to thrive on locally scarce resources (Harrison and Winfree 2015).

Our study results may also reflect some limitations of our methodologies. In our analyses, we pooled species with the same life-history traits for the fourth corner analysis. One limitation of this approach is that it may mask general responses (Williams et al. 2010). For example, if most large bees increased in response to urbanization but one abundant, small bee decreased, decline of the abundant species could obscure increases in the number of the others. We also acknowledge the difficulty of categorizing species by their functional traits. We justified our choices based on previous analyses. For example, following Forrest et al. (2015), we described species as either solitary or social, simplifying categories together. This means that socially polymorphic species such as Halictus rubicundus, which can have both eusocial and non-eusocial relatives within populations, was classified as social.

Conclusion: ecological applications

We confirm that bee abundance and richness respond to urbanization (Guenat et al. 2019; Ballare et al. 2019). Urbanization was associated with increases to bee richness and decreases to bee abundance, suggesting that while multiple species can utilize urban systems, their populations are low in abundance. While landscape-scale urbanization is not easily managed by local community gardeners, examining trait diversity reveals that local-scale management (e.g. creating nesting habitat) could affect the assemblage of the bee community. While we contribute to a growing number of studies that suggest traits can be used to understand how bees respond to habitat management, we also highlight that the trait-based literature has found mixed impacts of urbanization on bee traits (Tonietto et al. 2011; Normandin et al. 2017; Fitch et al. 2019; Wilson and Jamieson 2019). These discrepancies are possibly due to how urbanization and traits are measured. Approaches that utilize distance-based frameworks to measure trait diversity and conceptualize species traits relative to a community average (Laliberté and Legendre 2010; Coux et al. 2016) may be more predictive of how bee communities respond to change landscapes and offer a promising future methodological direction. Understanding the impact of anthropogenic change on bee communities is important because changes in the composition of species and traits likely influences the functioning of urban ecosystems (Faeth et al. 2001). This is especially relevant in urban agricultural systems like gardens, where bees support pollination services of urban crops (Potter and LeBuhn 2015; Lowenstein et al. 2015). For urban pollinators, we need a greater understanding of which bee traits influence species vulnerability to disturbance and which influence their ability to provision ecosystem services.

Data availability

Data is available on a public repository at github.com/hamutahlc/beetraits.

Code availability

Code is available on a public repository at github.com/hamutahlc/beetraits.

References

Ballare KM, Neff JL, Ruppel R, Jha S (2019) Multi-scalar drivers of biodiversity: local management mediates wild bee community response to regional urbanization. Ecol Appl 29(3):e01869

Banaszak-Cibicka W, Żmihorski M (2012) Wild bees along an urban gradient: winners and losers. J Insect Conserv 16(3):331–343

Banner KM, Higgs MD (2017) Considerations for assessing model averaging of regression coefficients. Ecol Appl 27(1):78–93

Bartomeus I, Ascher JS, Gibbs J, Danforth BN, Wagner DL, Hedtke SM, Winfree R (2013) Historical changes in northeastern US bee pollinators related to shared ecological traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(12):4656–4660

Blüthgen N, Klein AM (2011) Functional complementarity and specialisation: the role of biodiversity in plant–pollinator interactions. Basic Appl Ecol 12(4):282–291

Bommarco R, Biesmeijer JC, Meyer B, Potts SG, Pöyry J, Roberts SP, Öckinger E (2010) Dispersal capacity and diet breadth modify the response of wild bees to habitat loss. Proc R Soc B 277(1690):2075–2082

Buchholz S, Gathof AK, Grossmann AJ, Kowarik I, Fischer LK (2020) Wild bees in urban grasslands: urbanisation, functional diversity and species traits. Landsc Urban Plann 196:103731

Burkman CE, Gardiner MM (2014) Urban greenspace composition and landscape context influence natural enemy community composition and function. Biol Control 75:58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2014.02.015

Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2004) Multimodal inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol Methods Res 33:261–304

Cade BS (2015) Model averaging and multimodal inferences. Ecology 96:2370–2382

Cadotte MW, Carscadden K, Mirotchnick N (2011) Beyond species: functional diversity and the maintenance of ecological processes and services. J Appl Ecol 48(5):1079–1087

Cane JH (1987) Estimation of bee size using intertegular span (Apoidea). J Kansas Entomol Soc 60:145–147

Cane JH (2015) Landscaping pebbles attract nesting by the native ground-nesting bee Halictus rubicundus (Hymenoptera: Halictidae). Apidologie 46(6):728–734

Cane JH, Minckley RL, Kervin LJ, Roulston TAH, Williams NM (2006) Complex responses within a desert bee guild (Hymenoptera: Apiformes) to urban habitat fragmentation. Ecol Appl 16(2):632–644

Carper AL, Adler LS, Warren PS, Irwin RE (2014) Effects of suburbanization on forest bee communities. Environ Entomol 43(2):253–262. https://doi.org/10.1603/EN13078

Clough Y, Putra DD, Pitopang R, Tscharntke T (2009) Local and landscape factors determine functional bird diversity in Indonesian cacao agroforestry. Biol Conserv 142(5):1032–1041

Coux C, Rader R, Bartomeus I, Tylianakis JM (2016) Linking species functional roles to their network roles. Ecol Lett 19(7):762–770

De Palma A, Kuhlmann M, Roberts SP, Potts SG, Börger L, Hudson LN, Purvis A (2015) Ecological traits affect the sensitivity of bees to land-use pressures in European agricultural landscapes. J Appl Ecol 52(6):1567–1577

Diaz S, Cabido M, Casanoves F (1998) Plant functional traits and environmental filters at a regional scale. J Veg Sci 9(1):113–122

Dray S, Dufour AB (2007) The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J Stat Softw 22(4):1–20

Dray S, Legendre P (2008) Testing the species traits–environment relationships: the fourth-corner problem revisited. Ecology 89(12):3400–3412

Dray S, Choler P, Doledec S, Peres-Neto PR, Thuiller W, Pavoine S, ter Braak CJ (2014) Combining the fourth-corner and the RLQ methods for assessing trait responses to environmental variation. Ecology 95(1):14–21

Egerer MH, Arel C, Otoshi MD, Quistberg RD, Bichier P, Philpott SM (2017) Urban arthropods respond variably to changes in landscape context and spatial scale. J Urban Ecol 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/jue/jux001

Egerer M, Cecala JM, Cohen H (2020) Wild bee conservation within urban gardens and nurseries: effects of local and landscape management. Sustainability 12(1):293

Eggenberger H, Frey D, Pellissier L, Ghazoul J, Fontana S, Moretti M (2019) Urban bumblebees are smaller and more phenotypically diverse than their rural counterparts. J Anim Ecol 88(10):1522–1533

Faeth SH, Saari S, Bang C (2001) Urban biodiversity: patterns, processes and implications for conservation. eLS. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470015902a0023572

Fetridge ED, Ascher JS, Langellotto GA (2008) The bee fauna of residential gardens in a suburb of New York City (Hymenoptera: Apoidea). Ann Entomol Soc Am 101(6):1067–1077

Fischer LK, Eichfeld J, Kowarik I, Buchholz S (2016) Disentangling urban habitat and matrix effects on wild bee species. PeerJ 4:e2729

Fitch G, Wilson CJ, Glaum P, Vaidya C, Simao MC, Jamieson MA (2019) Does urbanization favour exotic bee species? Implications for the conservation of native bees in cities. Biol Lett 15(12):20190574

Forrest JR, Thorp RW, Kremen C, Williams NM (2015) Contrasting patterns in species and functional-trait diversity of bees in an agricultural landscape. J Appl Ecol 52(3):706–715

Fortel L, Henry M, Guilbaud L, Guirao AL, Kuhlmann M, Mouret H, Vaissière BE (2014) Decreasing abundance, increasing diversity and changing structure of the wild bee community (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) along an urbanization gradient. PLoS ONE 9(8):e0104679

Fowler-Walker MJ, Wernberg T, Connell SD (2006) Differences in kelp morphology between wave sheltered and exposed localities: morphologically plastic or fixed traits? Mar Biol 148(4):755–767

Fox J, Weisberg S, Adler D, Bates D, Baud-Bovy G, Ellison S, Heilberger R (2018) Package “car”: companion to applied regression. Computer software package at. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/car/index.html

Frankie GW, Thorp RW, Schindler M, Hernandez J, Ertter B, Rizzardi M (2005) Ecological patterns of bees and their host ornamental flowers in two northern California cities. J Kansas Entomol Soc 78(3):227–246

Gadagkar R (1990) Evolution of eusociality: the advantage of assured fitness returns. Philos Trans R Soc Lond 329(1252):17–25

Gathmann A, Tscharntke T (2002) Foraging ranges of solitary bees. J Anim Ecol 71(5):757–764

Gómez JM, Bosch J, Perfectti F, Fernández J, Abdelaziz M (2007) Pollinator diversity affects plant reproduction and recruitment: the tradeoffs of generalization. Oecologia 153(3):597–605

Goulson D, Nicholls E, Botías C, Rotheray EL (2015) Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 347(6229):1255957

Greenleaf SS, Williams NM, Winfree R, Kremen C (2007) Bee foraging ranges and their relationship to body size. Oecologia 153(3):589–596

Guenat S, Kunin WE, Dougill AJ, Dallimer M (2019) Effects of urbanisation and management practices on pollinators in tropical Africa. J Appl Ecol 56(1):214–224

Gunst RF (1983) Regresion analysis with multicollinear predictor variables: definition, derection, and effects. Commun Stat 12(19):2217–2260

Hall DM, Camilo GR, Tonietto RK, Ollerton J, Ahrné K, Arduser M, Goulson D (2017) The city as a refuge for insect pollinators. Conserv Biol 31(1):24–29

Hamblin AL, Youngsteadt E, López-Uribe MM, Frank SD (2017) Physiological thermal limits predict differential responses of bees to urban heat-island effects. Biol Lett 13(6):20170125

Harrell Jr FE, Dupont MC (2019) Package “hmisc”: Harrell Miscellaneous. Computer software package at. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Hmisc/index.html

Harrison T, Winfree R (2015) Urban drivers of plant-pollinator interactions. Funct Ecol 29(7):879–888

Härtel S, Steffan-Dewenter I (2014) Ecology: honey bee foraging in human-modified landscapes. Curr Biol 24(11):R524–R526

Hladik ML, Vandever M, Smalling KL (2016) Exposure of native bees foraging in an agricultural landscape to current-use pesticides. Sci Total Environ 542:469–477

Hoehn P, Tscharntke T, Tylianakis JM, Steffan-Dewenter I (2008) Functional group diversity of bee pollinators increases crop yield. Proc R Soc B 275(1648):2283–2291

Hoiss B, Krauss J, Potts SG, Roberts S, Steffan-Dewenter I (2012) Altitude acts as an environmental filter on phylogenetic composition, traits and diversity in bee communities. Proc R Soc B 279(1746):4447–4456

Homer C, Dewitz J, Jin S, Xian G, Costello C, Danielson P, Auch R (2020) Conterminous United States land cover change patterns 2001–2016 from the 2016 National Land Cover Database. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens 162:184–199

Hopfenmüller S, Steffan-Dewenter I, Holzschuh A (2014) Trait-specific responses of wild bee communities to landscape composition, configuration and local factors. PLoS ONE 9(8):e104439

Hopfenmüller S, Holzschuh A, Steffan-Dewenter I (2020) Effects of grazing intensity, habitat area and connectivity on snail-shell nesting bees. Biol Conserv 242:108406

Hulot FD, Lacroix G, Lescher-Moutoué F, Loreau M (2000) Functional diversity governs ecosystem response to nutrient enrichment. Nature 405(6784):340–344

Hülsmann M, von Wehrden H, Klein AM, Leonhardt SD (2015) Plant diversity and composition compensate for negative effects of urbanization on foraging bumble bees. Apidologie 46(6):760–770

Hung KLJ, Ascher JS, Davids JA, Holway DA (2019) Ecological filtering in scrub fragments restructures the taxonomic and functional composition of native bee assemblages. Ecology 100(5):e02654

Kassen R (2002) The experimental evolution of specialists, generalists, and the maintenance of diversity. J Evol Biol 15(2):173–190

Keddy PA (1992) A pragmatic approach to functional ecology. Funct Ecol 6(6):621–626

Kennedy CM, Lonsdorf E, Neel MC, Williams NM, Ricketts TH, Winfree R, Carvalheiro LG (2013) A global quantitative synthesis of local and landscape effects on wild bee pollinators in agroecosystems. Ecol Lett 16(5):584–599

Klein AM, Steffan-Dewenter I, Tscharntke T (2003) Fruit set of highland coffee increases with the diversity of pollinating bees. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B 270(1518):955–961

Knop E (2016) Biotic homogenization of three insect groups due to urbanization. Glob Change Biol 22(1):228–236

Krauss J, Alfert T, Steffan-Dewenter I (2009) Habitat area but not habitat age determines wild bee richness in limestone quarries. J Appl Ecol 46(1):194–202

Kremen C, Williams NM, Bugg RL, Fay JP, Thorp RW (2004) The area requirements of an ecosystem service: crop pollination by native bee communities in California. Ecol Lett 7(11):1109–1119

Laakso J, Setälä H (1999) Sensitivity of primary production to changes in the architecture of belowground food webs. Oikos. https://doi.org/10.2307/3546996

Laliberté E, Legendre P (2010) A distance-based framework for measuring functional diversity from multiple traits. Ecology 91(1):299–305

Langenheder S, Prosser JI (2008) Resource availability influences the diversity of a functional group of heterotrophic soil bacteria. Environ Microbiol 10(9):2245–2256

Lanner J, Kratschmer S, Petrović B, Gaulhofer F, Meimberg H, Pachinger B (2019) City dwelling wild bees: how communal gardens promote species richness. Urban Ecosyst. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-019-00902-5

Lavorel S, Díaz S, Cornelissen JHC, Garnier E, Harrison SP, McIntyre S, Urcelay C (2007) Plant functional types: are we getting any closer to the Holy Grail?. In: Terrestrial ecosystems in a changing world. Springer, Berlin, pp 149–164

Long EY, Krupke CH (2016) Non-cultivated plants present a season-long route of pesticide exposure for honey bees. Nat Commun 7(1):1–12

Lowenstein DM, Matteson KC, Xiao I, Silva AM, Minor ES (2014) Humans, bees, and pollination services in the city: the case of Chicago, IL (USA). Biodivers Conserv 23(11):2857–2874

Lowenstein DM, Matteson KC, Minor ES (2015) Diversity of wild bees supports pollination services in an urbanized landscape. Oecologia 179(3):811–821

Lowenstein DM, Matteson KC, Minor ES (2019) Evaluating the dependence of urban pollinators on ornamental, non-native, and ‘weedy’ floral resources. Urban Ecosyst 22(2):293–302

Maire V, Gross N, Börger L, Proulx R, Wirth C, Pontes LDS, Louault F (2012) Habitat filtering and niche differentiation jointly explain species relative abundance within grassland communities along fertility and disturbance gradients. New Phytol 196(2):497–509

Martins KT, Gonzalez A, Lechowicz MJ (2017) Patterns of pollinator turnover and increasing diversity associated with urban habitats. Urban Ecosyst 20(6):1359–1371

Matteson KC, Langellotto GA (2011) Small scale additions of native plants fail to increase beneficial insect richness in urban gardens. Insect Conserv Divers 4(2):89–98

Matteson KC, Ascher JS, Langellotto GA (2008) Bee richness and abundance in New York City urban gardens. Ann Entomol Soc Am 101(1):140–150

McKinney ML (2006) Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biol Conserv 127(3):247–260

Michener CD, McGinley RJ, Danforth BN (1994) The Bee Genera of North and Central America (Hymenoptera: Apoidea). Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington

Moretti M, De Bello F, Roberts SP, Potts SG (2009) Taxonomical vs. functional responses of bee communities to fire in two contrasting climatic regions. J Anim Ecol 78(1):98–108

MuMIn BK (2018) Multi-model inference. R package version 1.15. 6. 2016

Murray TE, Kuhlmann M, Potts SG (2009) Conservation ecology of bees: populations, species and communities. Apidologie 40(3):211–236

Norberg J, Swaney DP, Dushoff J, Lin J, Casagrandi R, Levin SA (2001) Phenotypic diversity and ecosystem functioning in changing environments: a theoretical framework. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98(20):11376–11381

Normandin É, Vereecken NJ, Buddle CM, Fournier V (2017) Taxonomic and functional trait diversity of wild bees in different urban settings. PeerJ 5:e3051

Öckinger E, Schweiger O, Crist TO, Debinski DM, Krauss J, Kuussaari M, Bommarco R (2010) Life-history traits predict species responses to habitat area and isolation: a cross-continental synthesis. Ecol Lett 13(8):969–979

Pardee GL, Philpott SM (2014) Native plants are the bee’s knees: local and landscape predictors of bee richness and abundance in backyard gardens. Urban Ecosyst 17(3):641–659

Persson AS, Rundlöf M, Clough Y, Smith HG (2015) Bumble bees show trait-dependent vulnerability to landscape simplification. Biodivers Conserv 24(14):3469–3489

Petchey OL, Gaston KJ (2006) Functional diversity: back to basics and looking forward. Ecol Lett 9(6):741–758

Philpott SM, Albuquerque S, Bichier P, Cohen H, Egerer MH, Kirk C, Will KW (2019) Local and landscape drivers of carabid activity, species richness, and traits in urban gardens in coastal California. Insects 10(4):112

Plascencia M, Philpott SM (2017) Floral abundance, richness, and spatial distribution drive urban garden bee communities. Bull Entomol Res 107(5):658–667

Potter A, LeBuhn G (2015) Pollination service to urban agriculture in San Francisco, CA. Urban Ecosyst 18(3):885–893

Potts SG, Biesmeijer JC, Kremen C, Neumann P, Schweiger O, Kunin WE (2010) Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol Evol 25(6):345–353

Quistberg RD, Bichier P, Philpott SM (2016) Landscape and local correlates of bee abundance and species richness in urban gardens. Environ Entomol 45(3):592–601

Rand TA, Tscharntke T (2007) Contrasting effects of natural habitat loss on generalist and specialist aphid natural enemies. Oikos 116(8):1353–1362

Rand TA, Tylianakis JM, Tscharntke T (2006) Spillover edge effects: the dispersal of agriculturally subsidized insect natural enemies into adjacent natural habitats. Ecol Lett 9(5):603–614

R Core Team (2020) A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Redhead JW, Dreier S, Bourke AF, Heard MS, Jordan WC, Sumner S, Carvell C (2016) Effects of habitat composition and landscape structure on worker foraging distances of five bumble bee species. Ecol Appl 26(3):726–739

Riedinger V, Renner M, Rundlöf M, Steffan-Dewenter I, Holzschuh A (2014) Early mass-flowering crops mitigate pollinator dilution in late-flowering crops. Landsc Ecol 29(3):425–435

Rocha EA, Fellowes MD (2020) Urbanisation alters ecological interactions: Ant mutualists increase and specialist insect predators decrease on an urban gradient. Sci Rep 10(1):1–8.https://doi.org/10.1603/EN13078

Rollings R, Goulson D (2019) Quantifying the attractiveness of garden flowers for pollinators. J Insect Conserv 23:803–817

Root RB (1973) Organization of a plant-arthropod association in simple and diverse habitats: the fauna of collards (Brassica oleracea). Ecol Monogr 43(1):95–124

Roulston TAH, Goodell K (2011) The role of resources and risks in regulating wild bee populations. Annu Rev Entomol 56:293–312

Schmid-Hempel P, Durrer S (1991) Parasites, floral resources and reproduction in natural populations of bumblebees. Oikos. https://doi.org/10.2307/3545499

Sha S, Vandermeer JH (2009) Constrasting bee foraging in response to resource scale and local habitat management. Oikos. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17523.x

Steffan-Dewenter I (2003) Importance of habitat area and landscape context for species richness of bees and wasps in fragmented orchard meadows. Conserv Biol 17(4):1036–1044

Steffan-Dewenter I, Tscharntke T (2000) Resource overlap and possible competition between honey bees and wild bees in central Europe. Oecologia 122(2):288–296

Steffan-Dewenter I, Klein AM, Gaebele V, Alfert T, Tscharntke T (2006) Bee diversity and plant-pollinator interactions in fragmented landscapes. Spec Gener Plant-Pollinator Interact 387–410

Threlfall CG, Walker K, Williams NS, Hahs AK, Mata L, Stork N, Livesley SJ (2015) The conservation value of urban green space habitats for Australian native bee communities. Biol Conserv 187:240–248

Tilman D (2001) Functional diversity. In: Levin SA (ed) Encyclopaedia of biodiversity. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 109–120

Tonietto R, Fant J, Ascher J, Ellis K, Larkin D (2011) A comparison of bee communities of Chicago green roofs, parks and prairies. Landsc Urban Plan 103(1):102–108

Tscharntke T, Sekercioglu CH, Dietsch TV, Sodhi NS, Hoehn P, Tylianakis JM (2008) Landscape constraints on functional diversity of birds and insects in tropical agroecosystems. Ecology 89(4):944–951

Tscharntke T, Tylianakis JM, Rand TA, Didham RK, Fahrig L, Batáry P, Ewers RM (2012) Landscape moderation of biodiversity patterns and processes-eight hypotheses. Biol Rev 87(3):661–685

Verboven HA, Brys R, Hermy M (2012) Sex in the city: reproductive success of Digitalis purpurea in a gradient from urban to rural sites. Landsc Urban Plan 106(2):158–164

Violle C, Navas ML, Vile D, Kazakou E, Fortunel C, Hummel I, Garnier E (2007) Let the concept of trait be functional! Oikos 116(5):882–892

Walker JA (2017) A defense of model averaging. bioRxiv 133785

Waser NM, Chittka L, Price MV, Williams NM, Ollerton J (1996) Generalization in pollination systems, and why it matters. Ecology 77(4):1043–1060

Wenninger A, Kim TN, Spiesman BJ, Gratton C (2016) Contrasting foraging patterns: testing resource-concentration and dilution effects with pollinators and seed predators. Insects 7(2):23

Williams NM, Crone EE, T’ai HR, Minckley RL, Packer L, Potts SG (2010) Ecological and life-history traits predict bee species responses to environmental disturbances. Biol Conserv 143(10):2280–2291

Wilson CJ, Jamieson MA (2019) The effects of urbanization on bee communities depends on floral resource availability and bee functional traits. PLoS ONE 14(12):e0225852

Winfree R, Aguilar R, Vázquez DP, LeBuhn G, Aizen MA (2009) A meta-analysis of bees’ responses to anthropogenic disturbance. Ecology 90(8):2068–2076

Woodard SH, Jha S (2017) Wild bee nutritional ecology: predicting pollinator population dynamics, movement, and services from floral resources. Curr Opin Insect Sci 21:83–90

Wray JC, Neame LA, Elle E (2014) Floral resources, body size, and surrounding landscape influence bee community assemblages in oak-savannah fragments. Ecol Entomol 39(1):83–93

Acknowledgements

M. Plascencia, P. Bichier, M. MacDonald, J. Burks, and R. Schreiber collected bees and vegetation data. M. Plascencia identified bees. K. Ennis assisted with measuring bee body size and with data analyses. M. Otoshi organized the landscape data. We thank the following gardens for allowing us to conduct research: Aptos Garden, Beach Flats Community Garden, Berryessa Garden, Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, Chinatown Community Garden, Coyote Creek Community Garden, El Jardín at Emma Prusch Park, The Forge at Santa Clara University, Giving Garden at Faith Lutheran Church, Homeless Garden Project, La Colina Community Garden, Laguna Seca Garden, The Live Oak Grange, MEarth at Carmel Valley Middle School, Mi Jardín Verde at All Saints’ Episcopal Church, Our Green Thumb Garden at Monterey Institute for International Studies, Salinas Garden at St. George’s Episcopal Church.

Funding

Funding was provided to HC by the Heller Grant for Graduate Student Research, the GK-12 UCSC SCWIBLES Training Program (NSF DGE-0947923) and Sigma Grants-in-Aid of Research. The National Science Foundation GRFP (Grant 2016-174835) supported MHE. Additional support came from USDA-NIFA Grant 2016-67019-25185 to SMP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HC led study design, participated in fieldwork, coordinated lab work and insect identification, and coordinated manuscript writing. ME analyzed the data and contributed to the manuscript. S–ST collected samples and identified them. SMP led site selection, field research design, fieldwork logistics and contributed to manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, H., Egerer, M., Thomas, SS. et al. Local and landscape features constrain the trait and taxonomic diversity of urban bees. Landsc Ecol 37, 583–599 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-021-01370-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-021-01370-z