Abstract

Context

Restoring landscape connectivity can mitigate fragmentation and improve population resilience, but functional equivalence of contrasting elements is poorly understood. Evaluating biodiversity outcomes requires examining assemblage-responses across contrasting taxa.

Objectives

We compared arthropod species and trait composition between contrasting open-habitat network elements: core patches, corridors (allowing individual dispersal and population percolation), and transient stepping-stones (potentially enhancing meta-population dynamics).

Methods

Carabids and spiders were sampled from core patches of grass-heath habitat (n = 24 locations across eight sites), corridors (trackways, n = 15) and recently-replanted clear-fells (transient patches, n = 19) set in a forest matrix impermeable to open-habitat arthropods. Species and trait (habitat association, diet, body size, dispersal ability) composition were compared by ordination and fourth corner analyses.

Results

Each network element supported distinct arthropod assemblages with differing functional trait composition. Core patches were dominated by specialist dry-open habitat species while generalist and woodland species contributed to assemblages in connectivity elements. Nevertheless, transient patches (and to a lesser degree, corridors) supported dry-open species characteristic of the focal grass-heath sites. Trait associations differed markedly among the three elements. Dispersal mechanisms and their correlates differed between taxa, but dry-open species in transient patches were characterised by traits favouring dispersal (large running hunter spiders and large, winged, herbivorous carabids), in contrast to wingless carabids in corridors.

Conclusions

Core patches, dispersal corridors and transient stepping-stones are not functionally interchangeable within this system. Semi-natural core patches supported a filtered subset of the regional fauna. Evidence for enhanced connectivity through percolation (corridors) or meta-population dynamics (stepping stones) differed between the two taxa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Restoring functional connectivity is promoted in conservation strategies to facilitate biodiversity resilience and population survival in the face of anthropogenic landscape fragmentation, land-use intensification and climate change (Chetkiewicz et al. 2006; DEFRA 2018; Isaac et al. 2018). At local scales, enhanced connectivity within regional landscapes may improve local population persistence by enhancing rescue effects and reducing detrimental impacts of fragmentation (Beier and Noss 1998; Damschen et al. 2006) while at greater scales, connectivity is advocated to facilitate population range-response to climatic change (e.g. Heller and Zavaleta 2009; Imbach et al. 2013). While the optimal level of site aggregation or dispersion may differ between the aims of enhancing local persistence or favouring large-scale range-expansion (Hodgson et al. 2011), functional connectivity at both scales requires appropriate interventions within local landscapes (Jongman et al. 2004, 2011). Within such local networks, although some generalist species may disperse through surrounding matrix habitats, for specialist species population connectivity often requires connectivity elements of suitable quality and type, with corridors, stepping stones, or a less hostile matrix (Bennett 2003) intended to improve dispersal and functional connectivity between ‘core patches’ or ‘ecological refuges’—relict fragments of natural or semi-natural habitat that have retained local species-populations over decadal timescales (Davis et al. 2013). Despite the abundance of literature promoting restoration of ecological networks the relative benefits of corridor linkages or stepping stones are poorly understood (Dolman 2012). Furthermore, few connectivity studies report community or assemblage responses, with research often focused on a few target species (Haddad et al. 2014). Conservation strategies seeking to restore ecological connectivity are best informed by understanding responses to connectivity elements of differing configurations across multiple taxa (Pedley et al. 2013b; Kormann et al. 2015; Albert et al. 2017). Additionally, examining responses in terms of assemblages’ trait- rather than species-composition supports generalisation to other ecological systems (McGill et al. 2006; Pedley and Dolman 2014; Santini et al. 2016).

Connectivity is often conceived as movement corridors enabling dispersal between primary habitat patches (Simberloff et al. 1992). Meta-analysis of movement, considering both direct (movement frequency and rate) and indirect (abundance and species richness in connected patches) measures, confirms corridors increase species’ movement in fragmented landscapes (Gilbert-Norton et al. 2010), potentially recolonising vacant habitat or enhancing persistence through population rescue (Lawson et al. 2012). For slowly-dispersing and matrix-sensitive species, corridors of suitable quality may allow population percolation over multiple generations (Bennett 2003), assisting range responses to climate change (Krosby et al. 2010). However, corridors, which by their nature are narrow with high edge-area ratios (Simberloff et al. 1992), may have assemblages filtered and modified by edge impacts (Ewers and Didham 2008; Campbell et al. 2011). Alternatively, stepping stones, a series of discrete, smaller patches intended to link otherwise isolated habitat blocks, may provide connectivity for mobile species capable of occasional dispersal across the intervening matrix (Schultz 1998). A reduced edge-area may mitigate edge impacts and offer better habitat suitability for specialist species, although assemblages may be filtered by colonisation ability (Kormann et al. 2015). Both of these types of connectivity elements are often advocated without explicit consideration of their relative efficacy or functional equivalence (e.g. Lawton et al. 2010), with limited analysis of the trade-offs between differing configurations and taxa.

For species associated with early-successional or physically-disturbed habitats, stepping-stone suitability may be short-lived, with more frequent dispersal required for meta-population persistence (Amarasekare and Possingham 2001; Johst et al. 2002; Loehle 2007). Similarly, cyclic or episodic landuse, including much habitat management practiced for conservation, the development and building phases of physical infrastructure projects, and crop or forestry rotations, may all provide short-lived opportunities for specialists able to colonise, exploit and move on from stepping stones. Understanding assemblage responses to differing configuration of habitat can inform whether biodiversity conservation strategies can take advantage of spatially discontinuous and transient patches, or instead require permanent and spatially continuous, connectivity elements.

Here, we examine arthropod (carabid and spider) trait and assemblage responses to open-habitat elements of contrasting configuration, comprising: ‘core patches’ (semi-natural grass-heath sites supporting large numbers of scarce and threatened taxa), grass-heath habitat persisting as ‘linear corridors’ (formed by trackways and verges), and transient stepping-stone patches (formed by infrequent systematic physical disturbance events), with the latter two potential connectivity elements embedded in a plantation matrix impermeable to open habitat specialists (Pedley 2012). A fundamental assumption of our study, is that assemblage richness and composition in the recently-created connecting elements has been shaped by patterns of individual dispersal and colonisation (following Gilbert-Norton et al. 2010), particularly for open-habitat species for which the matrix is impermeable. The use of terrestrial arthropods, particularly carabids and spiders, provides a useful group with which to examine landscape configuration as they are highly speciose, have high reproductive rates, respond quickly to environmental change and contain many different life history stratagems including dispersal, feeding and body size (Duffey 1968; Robinson 1981; Lovei and Sunderland 1996; Marc et al. 1999; Rainio and Niemela 2003).

We use this system to examine whether assemblages in transient patches and corridors within the plantation resembled those of the core patches, or instead have been filtered in ways that can be predicted by life history traits. Three alternative colonisation hypotheses are considered for these elements: (1) assemblages in transient stepping-stone and corridor elements resemble those of core patches; (2) assemblages in transient stepping-stone and corridor elements comprise a sub-set of species lacking many specialists restricted to core patches; (3) compared to assemblages within corridors, transient elements have greater representation of dispersive species. We predicted that (P1) assemblages developing in transient patches of open habitat will be represented by small-bodied, aerial-dispersing, habitat generalists, whereas (P2) corridors will have assemblages dominated by large-bodied, active-hunting generalists and that (P3) edge effects will increase the species number and diversity in connectivity elements compared to core patches, due to an influx of vagrant and generalist species.

Material and methods

Study area and design

The study region in eastern England is characterised by a semi-continental climate, sandy, nutrient-poor soil and historically supported extensive semi-natural grass-heath (Dolman and Sutherland 1992). Most grass-heath was converted to arable or forestry during the twentieth century, but remaining grass-heath sites support large numbers of scarce and threatened taxa, characterised by specialist coastal, continental and Mediterranean species dependent on physically disturbed open habitats (Dolman et al. 2012). Most of the remaining grass-heaths are designated for their conservation value but are fragmented and isolated. Regional conservation strategy seeks to improve habitat quality within these remaining grass-heaths, but also to restore functional connectivity between these ‘core patches’, with a focus on connectivity across and within extensive (185 km2) plantation forest (Thetford Forest, 0° 40′ E, 52° 27′ N) established over former open habitats in the early twentieth century.

During this study Thetford Forest was dominated by conifers, comprising 80% Corsican (Pinus nigra) and Scots (P. sylvestris) pine, managed by clear-felling (typically at 60–80 years) and replanting of even-aged management patches (hereafter ‘stands’). The forest landscape also contains open-habitat elements that differ in configuration. Narrow linear grass-heath ‘corridors’ are retained along trackways and their perennial verges that form an extensive (1290 km, 18 km2) open-habitat network permeating the forest landscape; following planting of the adjacent tree crop each trackway section provides open conditions for at least 20 years (see below). Larger transient stepping-stone patches (mean area of sampled patches: 9.0 ha ± 8.6 SD) are provided by clear-felled and replanted stands that offer short-lived (5–7 years) open-habitat that is variably connected to the corridor network (Fig. 1); these provide an excellent opportunity to examine colonisation after regular, systematic disturbance events. Vegetation regeneration in these transient patches is derived from persistent grass-heath seed-banks, augmented by zoochorous and aerial dispersal (Eycott et al. 2006a, b, 2007). Both trackways and transient patches provide fine-grained mosaics of modified grass-heath vegetation and bare mineral soil.

Assemblages of ‘core patches’ were characterised by sampling three locations within each of eight grass-heaths (mean area 106 ha ± 130 SD), either abutting or located within 2.5 km of the forest (mean = 0.72 km ± 1.11 SD). These included seven Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) designated for biodiversity under UK conservation legislation, of which five were also designated as Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) under the European Habitats Directive. Most were bordered by plantation forest and or intensive agriculture. Sampled areas comprised physically-disturbed habitats on which characteristic regional biota depend (Dolman et al. 2012), including areas grazed by sheep and rabbits and recently-ploughed areas associated with heathland management.

Nineteen transient stepping-stones were sampled. Prior to planting, stands were cleared of coarse woody debris (residue of clear-felling) and planting lines ploughed exposing extensive bare mineral substrate. Bare soil is encroached by ground vegetation within 3–4 years (Wright et al. 2009); tree cover then progresses with canopy closure after 20 years (Hemami et al. 2005). Extensive sampling shows open-habitat carabid and spider species persist for approximately five and seven years following planting (Lin et al. 2007; Pedley 2012). In the current study sampling considered stands up to 7 years (n = 5 for 1-year-, 3-year- and 5-year-old; n = 4 for 7-year-old). These transient open-habitat patches are fragmented, comprising approximately 6–8% of the 60–80 year growth cycle, while the surrounding plantation crop is impermeable to open-habitat species (Bertoncelj and Dolman 2013a, Pedley and Dolman unpublished). Transient patches available for sampling were clustered in the core plantation area (Fig. 1), but distance to the nearest grass-heath site was similar to that of the corridor elements (t = − 1.472, DF = 30.7, P = 0.151; transient mean = 2.1 km ± 1.0 SD, corridor mean = 1.7 km ± 0.6 SD).

Fifteen corridor elements were sampled. Trackways (mean width 12.7 m ± 3.9 SD) comprised two elements: a central wheeling with sparse vegetation and exposed substrate, flanked by vegetated verges. Many heathland-associated carabid and spider species have been recorded from this trackway network (Lin et al. 2007; Pedley et al. 2013a) but are excluded by shading from those trackways within or bordering older stands (≥ 20 years) (Pedley et al. 2013a). Sampled verges were each adjacent to thicket-aged stands (11–20 year old, following Hemami et al. (2005) and a mean of 0.78 km (± 0.25 SD) from the nearest other sampled trackway. To minimise shading effects, for trackways oriented east–west the northern-most verge was sampled, and for those oriented north–south the widest verge was sampled.

Arthropod sampling

Ground-active arthropods were sampled in 2009 by pitfall transects that formed the standardised unit of replication for analysis. Although a single sampling year may miss year-on-year differences in compositional detail of sampled assemblages, previous research on ground invertebrates in the study region has shown relatively stable species compositions (Lin et al. 2007; Pedley et al. 2013b). A single pitfall transect was placed in each of the 15 corridor elements. Two transects were placed within each of the 19 transient stepping-stones, separated by at least 50 m for independence. In each of the eight heathland sites, three independent transects were again separated by at least 50 m. We acknowledge that replicate transects sampled within each grass-heath site, and within each transient patch, are not spatially independent, and where possible control for this spatial pseudo-replication by including site identity as a random effect in subsequent analyses (see below).

Arthropod assemblages were sampled in each transect in May and again in June, the peak periods of arthropod abundance and activity, each time using six pitfall traps (each 7.5 cm deep, 6.5 cm diameter, filled with 50 ml of 70% ethylene glycol), set 15 m apart and opened for seven consecutive days. The two catches were pooled to give one composite sample per transect for subsequent analyses. In August 2009, vegetation height in each transect was assessed at 40 points using a sward stick (diameter 90 mm, weight 250 g, following Dolman and Sutherland 1992), and percentage of bare substrate visually estimated in 20 cm × 20 cm at each point. At each of these points the presence of key structural vegetation features (herbs, grasses, moss, lichen, shrub, and succulent) was also recorded, providing frequency per transect.

Carabid identification followed Luff (2007). Adult spiders were identified to species following Roberts (1987, 1996), juveniles and sub-adults with undeveloped reproductive structures were not identified. Analysis of spider assemblages was confined to ground-active species as sedentary invertebrates, such as many web-spinning spider, are poorly represented by pitfall catches (Topping and Sunderland 1992). Ecological and habitat affinities of identified species were classified following Luff (1998, 2007) for carabids and Harvey et al. (2002) and Roberts (1996) for spiders. Habitat affinities comprised: shaded woodland habitats, hereafter ‘woodland’; ‘generalist’ species of multiple or any mesic habitat; and ‘dry-open’ species associated with dry calcareous or acidic grassland, dry lowland heathland, dunes, sand or gravel pits. Open habitat connectivity elements therefore provide potential habitat for these ‘dry-open’ species that are excluded from (unable to percolate through) the closed-canopy forest matrix, but their presence depends on colonisation following dispersal.

Life history traits

Potential ecological factors that may determine assemblage responses to habitat elements were selected. We considered the life history traits of dispersal ability and foraging type (Pedley and Dolman 2014) for which published information was available at the individual species level (Online Resource 1). To ensure ordinal variables had a useable number of species per category, uncommon sub-categories were merged into broader classes. For spiders, aerial dispersal by ballooning (passively floating on silk threads) is considered effective for both short- and long-distance dispersal to colonise suitable habitat (Duffey 1998; Bell et al. 2005). Following Lambeets et al. (2008) and Langlands et al. (2011), we assigned spider species as ballooners according to the review by Bell et al. (2005). Carabid dispersal ability was assessed by wing morphology following Barbaro and van Halder (2009), with species exhibiting well-developed wing structures (macropterous) considered effective aerial dispersers, relative to those with rudimentary wing development (brachypterous). Wing-dimorphism (species with both long- and short-winged forms) was classified separately and is considered to provide dispersal advantages over brachypterous species, especially in temporally- and spatially-heterogeneous landscapes (Kotze and O'Hara 2003).

Analysis

Spiders and carabids were analysed separately, considering composite samples from individual transects. All analyses were carried out using the R statistical software (R Development Core Team 2018). Sampling efficiency was compared between landscape elements using sample-size based rarefaction curves calculated using the iNext package (Hsieh et al. 2016). Assemblage composition was visualised using non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) performed on a matrix of Bray–Curtis dissimilarities of abundance data (square root transformed and Wisconsin double standardisation) using the vegan package in R (Oksanen et al. 2018). Habitat structure variables were tested for association with community composition (NMDS) using the envfit function in vegan.

Arthropod assemblage composition was compared among core patches, corridors, and transient stepping-stones by multivariate Generalised Linear Models (GLMs) implemented in the mvabund package (Wang et al. 2012) using likelihood-ratio-tests with a negative binomial error distribution.

Richness and aggregate abundance of dry-open, generalist and woodland species were compared between landscape elements using Generalised Linear Mixed Models (GLMM). Site (stand, trackway or heath site) was included as a random effect as transects in corridors may capture greater beta diversity than replicates (separated by ≥ 50 m) within individual grass-heaths or transient stepping-stones. Models used Poisson or negative binomial error as appropriate, with landscape element means compared by Tukey pairwise comparisons. GLMMs were implemented in R using the glmer and glmmabmb functions from the packages lme4 (Bates et al. 2015) and glmmADMB.

Linkages within trait data (across species) were examined by a Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) applied to a trait-dissimilarity matrix (traits as variables, species as samples), using the Gower coefficient (Gower 1971) using the vegan package. The Gower coefficient was used as it handles mixed data types (nominal, ordinal or continuous—here standardised to zero mean and unit variance). Associations among traits were visualised by plotting trait vectors (from Spearman rank correlation in relation to the first two PCoA ordination axes) following Langlands et al. (2011); species habitat affinities were examined to visualise correlations with species traits. Species were also grouped by family (spiders) or tribe (carabids) to allow a qualitative examination of taxonomic influence in trait space. Phylogenetic character analysis was not possible due to unresolved phylogeny of both the spider and carabid assemblages.

Trait-specific responses to habitat types were analysed using fourth-corner analysis (Dray and Legendre 2008) that tests the link between all combinations of species traits and environmental attributes (here: core patch, corridor and transient landscape elements). By re-sampling three data matrices this approach indirectly relates matrix ‘R’ (environmental attributes × site) to matrix ‘Q’ (trait × species), via matrix ‘L’ (species-abundance × site). The fourth-corner procedure uses a generalised statistic SRLQ that is equivalent to the Pearson correlation coefficient r when trait (Q) and environment (R) variables are quantitative, to χ2 when both sets are qualitative, and to the correlation ratio η2 for mixed data (Dray and Legendre 2008).

The observed strength of linkage among traits and environmental attributes is assessed against that which may arise by chance, with null models determined by the observed structure of data matrices, using randomisation and permutation (Dray and Legendre 2008). Permutation Model 1 was used to test the null hypothesis that R is not linked to Q, by examining links between fixed species traits and fixed site characteristics. This model randomises species’ relative to site characteristics (permuting within each column of matrix L), but does not re-sample either the species-trait (matrix Q) or environment-site (matrix R) relations; appropriate (Dray and Legendre 2008) as traits were determined from the literature not empirical sampling, while the environment matrix was classified a priori. Prior to analysis, arthropod abundance data were square root transformed to reduce the effect of dominant species. We conducted the analysis first on all recorded species, then separately on only those associated with dry-open habitats, and finally for the subset of species recorded on grass-heath sites. Fourth-corner analyses were calculated with 9999 permutations, adjusted using false discovery rate correction procedures that account for repeated testing, using the ade4 package (Dray and Dufour 2007).

Results

We identified 3660 carabid individuals from 70 species and 12,483 spiders from 115 species, of which 11,521 spiders from 60 ground-active species were considered in analyses. Pitfall trapping within each landscape element effectively represented carabids and ground-spiders with species accumulation curves approaching asymptotes (Online Resource 2).

Carabid and spider assemblages were also successfully represented in ordination space using NMDS (stress: 0.21 and 0.19 respectively). Both carabid and spider composition (Fig. 2) differed significantly between each of the three landscape elements (mvabund GLMs: deviance = 758.9, P < 0.001; deviance = 817.8, P < 0.001 respectively; paired comparisons all P < 0.001). For carabids, assemblages of core patches were distinct on NMDS axis one, while transient and corridor carabid composition differed from each other on axis two (Fig. 2). Similarly for spider assemblages, axis one separated core patches from both connectivity elements while axis two again separated transient and corridor elements (Fig. 2) though to a lesser extent than for carabids.

Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination of ground-active carabid and spider assemblages (stress = 0.21 and 0.19 respectively). Open circles represent sampled transects and shaded ellipses the 95% confidence intervals of habitat element centroids. Significant habitat structure variables are displayed as vectors, longer vectors represent stronger association with species ordination. Online Resource 3 gives the vector, R2 and p-value for each environmental variable

For both arthropod groups, assemblage composition was significantly associated with all habitat structure variables (Fig. 2, Online Resource 3). Heath sites and assemblages were characterised by greater representation of lichens, succulents, bare ground and short swards; transient patches had taller vegetation, while corridors had greater cover of herbs, shrubs and grasses than transient elements (Fig. 2, Online Resource 3).

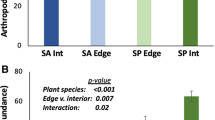

Arthropod species associated with dry-open habitats occurred across all three landscape elements. For dry-open carabids, mean species richness per sample was similar between core patches and both types of connectivity element, although their aggregate abundance was lower in corridors (Fig. 3, Online Resource 4). Rarefaction showed cumulative richness of dry-open carabids did not differ between core patches, corridors or transient patches (Online Resource 2). For dry-open spiders, mean richness per sample was similar between transient elements and core patches but lower in corridors, while abundance was lower in transient patches than core patches and was again lowest in corridors. Cumulative richness of specialist spiders was also significantly lower in corridors (Online Resource 2). Whilst core patches were dominated by dry-open species, both types of connectivity elements had greater representation of generalist and woodland species. For generalists, mean abundance and richness per sample were similar between transient and corridor elements for both taxa, with generalists particularly dominant in spider assemblages (Fig. 3). Rarefaction showed similar rates of species accumulation of generalists across elements for both taxa (Online Resource 2). Species associated with woodland were particularly scarce in the open grass-heath sites (with only two woodland spider individuals and 33 woodland carabid individuals recorded), but contributed to assemblages in both connectivity elements, with woodland spiders having greater mean abundance and richness in corridors than transient patches (Fig. 3).

Mean (± SE) of ground-active carabid and spider abundance and species richness shown separately for generalist, woodland-associated and dry-open habitat specialists, across three landscape elements. Means are calculated from standardized pitfall trap transects where each sample represents a composite of two sampling periods. Means that share a superscript (homogenous sub-sets, a–c) do not differ significantly (Tukey pairwise comparisons, P > 0.05). Online Resource 4 gives model statistics, P values and means for each comparison

Inter-relationship among traits

The first two axes of the PCoA represented 57.9% and 60.8% of the variation in traits among carabid and spider species respectively (Fig. 4, Online Resource 5), indicating inter-correlation among traits in each case. For carabids, PCoA axis one was positively associated with larger body size, brachypterous wing morphology and carnivorous feeding, and negatively associated with inter-correlated traits of herbivory and macroptery. Carabids associated with dry-open habitat were negatively related with PCoA axis one and positively with axis two, habitat generalists were negatively related with axis two. Distribution of carabid tribes within the PCoA suggested some phylogenetic pattern, with herbivory only found in the Zabrini (Amara and Curtonotus) and Harpalini (Harpalus, Bradycellus, Ophonus), which tended to be macropterous and mainly associated with dry-open habitats. Wing morphology was not strongly phylogenetically conserved in remaining carabid tribes.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) showing associations among ten traits of 69 carabid species and eight traits of 59 spider species. Trait vectors represent the Spearman correlations, with the length and direction indicating the relationship with composite PCoA axes (see Online Resource 1 for trait details and Online Resource 5 for trait loadings)

For spiders, PCoA axis one was positively associated with ambush hunting and habitat generalists and negatively associated with dry-open habitat association and a running hunting strategy. Spider PCoA axis two was positively associated with strongly inter-correlated traits of running hunting strategy and larger body size, and with flight dispersal, and was negatively associated with woodland habitat association and a stalking hunting strategy. The spider PCoA showed clustering of the main families (Fig. 4). The large, running hunters of the families Lycosidae, Gnaphosidae and Clubionidae were grouped towards the upper part of the ordination, but varied along axis one between species associated with dry-open habitats (in the upper-left of the ordination) and generalist species (upper right). Thomisidae, Theridiidae and Salticidae, were associated with ambush and stalking hunting strategies (lower part of the ordination) and tended to be smaller-bodied and habitat generalist or woodland-associated species.

Species traits among landscape elements

Fourth corner analysis revealed substantial differences in the trait composition of assemblages between the three landscape elements. Of the seven carabid and five spider traits tested, most correlated significantly with at least one landscape element (Table 1). Notably, all traits that significantly correlated with transient and corridor elements showed an opposite direction of correlation between these connectivity element types. Both carabid and spider assemblages in transient patches were correlated significantly with larger body size. Transient patches were also positively correlated with a carnivorous diet for carabids and with a running-hunting strategy for spiders. Importantly, traits conveying an increasing dispersal ability by flight (carabid macroptery) or aerial drift (spider ballooning) were not positively correlated with either type of connectivity element. For carabids, macroptery was negatively correlated with corridors, while for spiders ballooning was negatively correlated with transient elements. Wing-dimorphism for carabids was positively correlated with corridors and core patches, but negatively correlated with transient elements. Trait correlations tended to be reversed between core patches and transient elements; for example, small-bodied herbivorous carabids and small-bodied ambush-hunting spiders were correlated with core patches.

When considering only those species associated with dry-open habitats, several important trait-habitat correlations were apparent. For dry-open carabids, corridors were correlated with a carnivorous diet and lack of flight dispersal (brachyptery), while transient elements were correlated with large-bodied, herbivores with flight dispersal (Table 1). For dry-open habitat spiders, transient elements were again correlated with large, running hunters lacking ballooning dispersal, while corridors were not correlated with particular traits. Finally, restricting fourth-corner procedures to only species recorded in core patches did not provide any addition correlations for either taxa (Online Resource 6) with results largely consistent to previous analyses of the entire assemblage.

Discussion

Ground-active carabid and spider assemblages in core patches, transient stepping-stones and corridor connectivity elements differed in both species composition and trait representation, suggesting filtering by traits. Consequently connectivity elements differed in functional composition, both from each other and from the remaining grass heaths, but nevertheless increased beta diversity at the landscape-scale and supported obligate dry-open habitat species characteristic of core patches of grass heath. While corridors contained far fewer dry-open individuals than core patches, transient stepping-stone elements had similar mean dry-open richness to that in core patches. Our data on trait filtering did not resolve to generalised colonisation hypotheses that cut across these two taxa, due to differences between beetles and spiders in dispersal mechanisms and also their patterns of associations among traits. However, patterns regarding habitat association, generalist domination of connectivity elements, and increased species diversity in connectivity elements were consistent with our predictions (P3), while dispersal, habitat structure (patch quality) and edge effects (patch configuration) all appeared to influence differences in trait composition between elements.

Assemblage composition among landscape elements

We predicted that generalist species would dominate the connectivity elements and that richness and abundance would be greater in these patches, as expected from edge- and ecotone-effects. We found that generalist species made up a large proportion of the carabid assemblage and dominated spider assemblages, in both types of connectivity elements, with greater overall species richness of both taxa than in core patches of grass heath habitat. While both types of connectivity element also contained significant numbers of specialist carabids, core patches contained few species that were not specialists of dry-open habitat. Our results are consistent with others that find generalist species resilient to landscape change and dominant in disturbed or human-altered landscapes (Robinson and Sutherland 2002; Ewers and Didham 2008; Smith et al. 2015). As generalist species tend to be those associated with invasions and also better able to cope with changing, fragmented and disturbed ecosystems (Marvier et al. 2004), large numbers of generalists may be considered a concern for the conservation of natural and semi-natural assemblages.

Compositional edge effects are well known for forest boundaries (Downie et al. 1996; Muff et al. 2009; Campbell et al. 2011; Kowal and Cartar 2012); Ewers and Didham (2008) found increased beetle diversity at forest/grassland boundaries with compositional differences extending over 1 km. The greater richness of generalist and woodland-associated species within our corridor and transient elements, than in core patches, may partly be attributable to an influx of ‘vagrants’ from the adjacent matrix. Inflated species richness in narrow and small habitat patches is well documented for invertebrates (Halme and Niemela 1993; Driscoll and Weir 2005). Webb and Hopkins (1984) found that small heathland fragments supported greater invertebrate richness than larger intact sites, while Halme and Niemela (1993) found similar patterns in carabids inhabiting small forest fragments in Finland. In the current study it is likely that the narrow shape of corridors and the relatively small size of transient elements (and hence large edge ratios), favoured the incursion of woodland and generalist species from the matrix.

However, the greater species richness in connectivity elements also reflects the greater structural heterogeneity of habitats within these elements (Bieringer et al. 2013), not just edge-incursion (‘spill-over’) from the matrix. Both types of connectivity element contained a juxtaposition of: open micro-sites with bare disturbed mineral soil (trackway wheelings and ploughed planting rows), taller grassy herbaceous vegetation (trackway verges and baulks between planting rows) and woody ecotones at their margins, providing opportunities for species associated with these individual habitats but also those requiring micro-habitat juxtaposition and mosaics (Dolman et al. 2012). Similarly, Driscoll and Weir (2005) found linear strips of Australian mallee habitat were species-rich due to both ‘strip-specialists’ and matrix species. Assemblages in the core patches of grass heath habitat may represent not so much a pristine reference sample, but a sub-set of the landscape-wide biota filtered to exclude generalist and woodland associated species. This reflects the historic development of heathland from degraded pasture-woodland (Fuller et al. 2017).

Importantly, we found that the ground-active carabid and spider assemblages in connectivity elements were significantly different to each other as well as to assemblages of core patches. Although generalist abundance and richness did not differ between transient stepping-stones and corridor elements for either arthropod group, the mean richness and abundance of specialist dry-open associated arthropods was greater in transient stepping-stone elements than in corridors. For spiders, both mean (per sample) and cumulative (measured through rarefaction) specialist richness were similar between transient elements and core patches, but significantly lower in corridors. This is despite an expectation of efficient dispersal in linear elements with resistant (i.e. internally reflecting) borders set in a ‘hard’ matrix (i.e. one that is unlikely to provide dispersal or breeding habitat for target species) (Baum et al. 2004; Ockinger and Smith 2008; Bertoncelj and Dolman 2013b). This is also contrary to findings for a Hempiteran species, where in a soft (low-resistance) matrix, both corridors and stepping stones significantly improved connectivity, but in a hard matrix stepping-stone elements did not improve dispersal over non-connected controls (Baum et al. 2004). Despite the expectation of greater ease of colonisation along linear elements in a non-permeable matrix, other mechanisms may contribute to the greater abundance of specialist dry-open associated species in transient stepping-stones. First, although corridors are often conceptualised as conduits for individual movement and colonisation between habitat patches, diffuse resident populations may breed and disperse by percolation over several generations. Second, the larger transient patches, with reduced shading by adjacent forest and extensive disturbed mineral soil, may have provided greater habitat suitability for specialists than provided by corridors. Third, the larger size of transient patches relative to narrow corridors may have facilitated their colonisation by aerial-dispersing species.

Trait filtering

We predicted that assemblages developing in transient patches of open habitat would be represented by small-bodied, aerial-dispersing species, whereas corridors would be dominated by large-bodied, active-hunters. Trait correlations were in fact opposite to this prediction. However, while small body size and traits conveying greater dispersal ability were not more prevalent in transient patches overall; when analyses were confined to specialists of dry-open habitat (that are excluded from and do not percolate through the matrix), flight dispersal significantly correlated with transient elements for carabids. Where a significant trait correlation was detected with both corridor and transient elements, these were in opposing directions, indicating differential filtering of assemblages in these connectivity elements.

Differences in dispersal trait correlations were evident between the two arthropod groups and no consistent functional response to either connectivity type was found. The ability to disperse aerially is seen as a key trait for insects colonising unstable habitat (Roff 1990; Ribera et al. 2001) and ballooning spiders are often considered early colonists to newly-opened or disturbed habitat, such as after volcanic eruptions (Crawford et al. 1995) or in agricultural fields (Nyffeler and Sunderland 2003; Schmidt and Tscharntke 2005). Prevalence of aerial dispersal was only significantly greater in core patches for spiders and in transient patches for dry-open carabids. The findings for dry-open carabids are consistent with results in other systems (Gobbi et al. 2007; Moretti and Legg 2009; Wamser et al. 2012). Moretti and Legg (2009) reported large, highly-mobile insects respond to disturbance caused by regular winter fires, while Gobbi et al. (2007) found that younger sites with less stable soil conditions favouring greater representation of winged carbids in an alpine glacial chronosequence. In our long-lived corridors, dry-open carabids consisted of flightless carnivorous carabids, consistent with results from other stable or linear connectivity elements (Ribera et al. 2001; Wamser et al. 2012).

While disturbed and early-successional habitats have greater representation of flight capable species (Gutierrez and Menendez 1997; Ribera et al. 2001; Pedley and Dolman 2014), landscape configuration may also influence species distributions at the regional scale. Negative correlation of ballooning capable spiders with transient stepping-stone elements may in part be due to fragmentation of suitable habitat; with passive dispersal representing a high-risk strategy for narrow-niche species in fragmented landscapes. Bonte et al. (2003b) showed that specialist xerophilic spiders in fragmented sand dune habitat were less likely to balloon than habitat generalists. We found generalists were associated with flight dispersal for spiders but not for carabids, although brachyptery was associated with woodland carabid species, as expected by affinity of flightless species to more stable habitats (Ribera et al. 2001; Pedley and Dolman 2014).

For local dispersal, terrestrial movement alone may be sufficient for many ground-active species (Samu et al. 2003; Brouwers and Newton 2009). In the current study, large carabids and spiders were correlated with transient stepping-stone elements but not corridors, even when analysis was restricted to dry-open specialists. Results of a systematic review by Brouwers and Newton (2009) showed that larger carabids covered more ground per day than small species, likely due to both greater food requirements (Lovei and Sunderland 1996) and greater movement capability. Kormann et al. (2015) also found larger arthropods tended to benefit more from increased landscape connectivity, in the form of more closely-clustered grassland fragments, than did smaller species. For spiders, larger body size was associated with running hunters, of which Lycosidae made up the majority of the sampled assemblage. These running hunters have potential terrestrial dispersal distances of several hundred metres over a lifetime, with daily ranges recorded between 2-50 m (Kiss and Samu 2000; Bonte et al. 2003a, 2007). Such lifetime distances combined with high daily actively rates may explain the positive correlation of running hunters with transient patches, compared to less active hunting strategies (ambush and stalking) that are associated with smaller body size in spiders.

Conclusions

Concepts introduced through the theory of island biogeography and metapopulation dynamics suggest increasing habitat fragmentation will restrict species with poor dispersal to persistent refuges, while those with enhanced dispersal ability can take advantage of transient and connecting habitat elements. In the plantation landscape studied here, we found that the assemblages in core patches, corridors and transient stepping-stones were dissimilar in terms of both species’ composition and trait representation. Nevertheless, transient elements supported similar richness of characteristic dry-open associated specialists for which remnant heaths are designated. Dry-open habitat species in these transient patches were predominately large running spiders and large herbivorous carabids. However, dispersal strategies for these two arthropod groups were likely very different. In contrast, narrow linear corridors were less favourable to the open heathland assemblage, with spiders dominated by generalists. To provide connectivity for less-mobile species and taxa, corridors should reduce edge-related effects, as wider higher-quality corridors are likely to support more specialist species (Lees and Peres 2008; Pedley et al. 2013a). Carabids’ ability for directional flight, compared to spiders’ passive ballooning, may explain their greater ability to take advantage of transient connectivity elements within complex landscapes. Contrasts between carabids and spiders in their response to landscape configuration, emphasise the need for assessments to examine multiple taxa before making generalisations. Dispersal corridors and transient stepping-stones provided different trait and functional composition and were not interchangeable in this system.

References

Albert CH, Rayfield B, Dumitru M, Gonzalez A (2017) Applying network theory to prioritize multispecies habitat networks that are robust to climate and land-use change. Conserv Biol 31:1383–1396

Amarasekare P, Possingham H (2001) Patch dynamics and metapopulation theory: the case of successional species. J Theor Biol 209:333–344

Barbaro L, van Halder I (2009) Linking bird, carabid beetle and butterfly life-history traits to habitat fragmentation in mosaic landscapes. Ecography 32:321–333

Bates D, Machler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67:1–48

Baum KA, Haynes KJ, Dillemuth FP, Cronin JT (2004) The matrix enhances the effectiveness of corridors and stepping stones. Ecology 85:2671–2676

Beier P, Noss RF (1998) Do habitat corridors provide connectivity? Conserv Biol 12:1241–1252

Bell JR, Bohan DA, Shaw EM, Weyman GS (2005) Ballooning dispersal using silk: world fauna, phylogenies, genetics and models. Bull Entomol Res 95:69–114

Bennett AF (2003) Linkages in the landscape: the role of corridors and connectivity in wildlife conservation, 2nd edn. IUCN, Gland

Bertoncelj I, Dolman PM (2013a) Conservation potential for heathland carabid beetle fauna of linear trackways within a plantation forest. Insect Conserv Divers 6:300–308

Bertoncelj I, Dolman PM (2013b) The matrix affects trackway corridor suitability for an arenicolous specialist beetle. J Insect Conserv 17:503–510

Bieringer G, Zulka KP, Milasowszky N, Sauberer N (2013) Edge effect of a pine plantation reduces dry grassland invertebrate species richness. Biodivers Conserv 22:2269–2283

Bonte D, Lens L, Maelfait JP, Hoffmann M, Kuijken E (2003a) Patch quality and connectivity influence spatial dynamics in a dune wolfspider. Oecologia 135:227–233

Bonte D, Van Belle S, Maelfait JP (2007) Maternal care and reproductive state-dependent mobility determine natal dispersal in a wolf spider. Anim Behav 74:63–69

Bonte D, Vandenbroecke N, Lens L, Maelfait JP (2003b) Low propensity for aerial dispersal in specialist spiders from fragmented landscapes. Proc R Soc Lond B 270:1601–1607

Brouwers NC, Newton AC (2009) Movement rates of woodland invertebrates: a systematic review of empirical evidence. Insect Conserv Divers 2:10–22

Campbell RE, Harding JS, Ewers RM, Thorpe S, Didham RK (2011) Production land use alters edge response functions in remnant forest invertebrate communities. Ecol Appl 21:3147–3161

Chetkiewicz CLB, Clair CCS, Boyce MS (2006) Corridors for conservation: Integrating pattern and process. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 37:317–342

Crawford RL, Sugg PM, Edwards JS (1995) Spider arrival and primary establishment on terrain depopulated by volcanic eruption at Mount St-Helens, Washington. Am Midl Nat 133:60–75

DEFRA (2018) A green future: our 25 year plan to improve the environment. DEFRA, London

Damschen EI, Haddad NM, Orrock JL, Tewksbury JJ, Levey DJ (2006) Corridors increase plant species richness at large scales. Science 313:1284–1286

Davis J, Pavlova A, Thompson R, Sunnucks P (2013) Evolutionary refugia and ecological refuges: key concepts for conserving Australian arid zone freshwater biodiversity under climate change. Glob Change Biol 19:1970–1984

Dolman PM (2012) Mechanisms and processes underlying landscape structure effects on bird populations. In: Fuller RJ (ed) Birds and habitat: relationships in changing landscapes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 93–124

Dolman PM, Panter CJ, Mossman HL (2012) The biodiversity audit approach challenges regional priorities and identifies a mismatch in conservation. J Appl Ecol 49:986–997

Dolman PM, Sutherland WJ (1992) The ecological changes of breckland grass heaths and the consequences of management. J Appl Ecol 29:402–413

Downie IS, Coulson JC, Butterfield JEL (1996) Distribution and dynamics of surface-dwelling spiders across a pasture-plantation ecotone. Ecography 19:29–40

Dray S, Dufour A (2007) The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J Stat Softw 22:1–20

Dray S, Legendre P (2008) Testing the species traits-environment relationships: the fourth-corner problem revisited. Ecology 89:3400–3412

Driscoll DA, Weir T (2005) Beetle responses to habitat fragmentation depend on ecological traits, habitat condition, and remnant size. Conserv Biol 19:182–194

Duffey E (1968) An ecological analysis of spider fauna of sand dunes. J Anim Ecol 37:641–674

Duffey E (1998) Aerial dispersal in spiders. In: Proceedings of the 17th European Colloquium of Arachnology, Edinburgh, pp 187–191

Ewers RM, Didham RK (2008) Pervasive impact of large-scale edge effects on a beetle community. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:5426–5429

Eycott AE, Watkinson AR, Dolman PM (2006a) Ecological patterns of plant diversity in a plantation forest managed by clearfelling. J Appl Ecol 43:1160–1171

Eycott AE, Watkinson AR, Dolman PM (2006b) The soil seedbank of a lowland conifer forest: the impacts of clear-fell management and implications for heathland restoration. For Ecol Manag 237:280–289

Eycott AE, Watkinson AR, Hemami MR, Dolman PM (2007) The dispersal of vascular plants in a forest mosaic by a guild of mammalian herbivores. Oecologia 154:107–118

Fuller RJ, Williamson T, Barnes G, Dolman PM (2017) Human activities and biodiversity opportunities in pre-industrial cultural landscapes: relevance to conservation. J Appl Ecol 54:459–469

Gilbert-Norton L, Wilson R, Stevens JR, Beard KH (2010) A meta-analytic review of corridor effectiveness. Conserv Biol 24:660–668

Gobbi M, Rossaro B, Vater A, De Bernardi F, Pelfini M, Brandmayr P (2007) Environmental features influencing Carabid beetle (Coleoptera) assemblages along a recently deglaciated area in the Alpine region. Ecological Entomology 32:682–689

Gower JC (1971) General coefficient of similarity and some of its properties. Biometrics 27:857

Gutierrez D, Menendez R (1997) Patterns in the distribution, abundance and body size of carabid beetles (Coleoptera: Caraboidea) in relation to dispersal ability. J Biogeogr 24:903–914

Haddad NM, Brudvig LA, Damschen EI, Evans DM, Johnson BL, Levey DJ, Orrock JL, Resasco J, Sullivan LL, Tewksbury JJ, Wagner SA, Weldon AJ (2014) Potential negative ecological effects of corridors. Conserv Biol 28:1178–1187

Halme E, Niemela J (1993) Carabid beetles in fragments of coniferous forest. Ann Zool Fenn 30:17–30

Harvey P, Nellist D, Telfer M (2002) Provisional atlas of british spiders (Arachnida, Araneae), vols 1, 2. Biological Records Centre, Abbots Ripton

Heller NE, Zavaleta ES (2009) Biodiversity management in the face of climate change: a review of 22 years of recommendations. Biol Conserv 142:14–32

Hemami MR, Watkinson AR, Dolman PM (2005) Population densities and habitat associations of introduced muntjac Muntiacus reevesi and native roe deer Capreolus capreolus in a lowland pine forest. For Ecol Manag 215:224–238

Hodgson JA, Thomas CD, Cinderby S, Cambridge H, Evans P, Hill JK (2011) Habitat re-creation strategies for promoting adaptation of species to climate change. Conserv Lett 4:289–297

Hsieh TC, Ma KH, Chao A (2016) iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods Ecol Evol 7:1451–1456

Imbach PA, Locatelli B, Molina LG, Ciais P, Leadley PW (2013) Climate change and plant dispersal along corridors in fragmented landscapes of Mesoamerica. Ecol Evol 3:2917–2932

Isaac NJB, Brotherton PNM, Bullock JM, Gregory RD, Boehning-Gaese K, Connor B, Crick HQP, Freckleton RP, Gill JA, Hails RS, Hartikainen M, Hester AJ, Milner-Gulland EJ, Oliver TH, Pearson RG, Sutherland WJ, Thomas CD, Travis JMJ, Turnbull LA, Willis K, Woodward G, Mace GM (2018) Defining and delivering resilient ecological networks: Nature conservation in England. J Appl Ecol 55:2537–2543

Johst K, Brandl R, Eber S (2002) Metapopulation persistence in dynamic landscapes: the role of dispersal distance. Oikos 98:263–270

Jongman RHG, Bouwma IM, Griffioen A, Jones-Walters L, Van Doorn AM (2011) The pan European ecological network: PEEN. Landsc Ecol 26:311–326

Jongman RHG, Kulvik M, Kristiansen I (2004) European ecological networks and greenways. Landsc Urban Plan 68:305–319

Kiss B, Samu F (2000) Evaluation of population densities of the common wolf spider Pardosa agrestis (Araneae: Lycosidae) in Hungarian alfalfa fields using mark-recapture. Eur J Entomol 97:191–195

Kormann U, Rosch V, Batary P, Tscharntke T, Orci KM, Samu F, Scherber C (2015) Local and landscape management drive trait-mediated biodiversity of nine taxa on small grassland fragments. Divers Distrib 21:1204–1217

Kotze DJ, O'Hara RB (2003) Species decline—but why? Explanations of carabid beetle (Coleoptera, Carabidae) declines in Europe. Oecologia 135:138–148

Kowal VA, Cartar RV (2012) Edge effects of three anthropogenic disturbances on spider communities in Alberta's boreal forest. J Insect Conserv 16:613–627

Krosby M, Tewksbury J, Haddad NM, Hoekstra J (2010) Ecological connectivity for a changing climate. Conserv Biol 24:1686–1689

Lambeets K, Vandegehuchte ML, Maelfait JP, Bonte D (2008) Understanding the impact of flooding on trait-displacements and shifts in assemblage structure of predatory arthropods on river banks. J Anim Ecol 77:1162–1174

Langlands PR, Brennan KEC, Framenau VW, Main BY (2011) Predicting the post-fire responses of animal assemblages: testing a trait-based approach using spiders. J Anim Ecol 80:558–568

Lawson CR, Bennie JJ, Thomas CD, Hodgson JA, Wilson RJ (2012) Local and landscape management of an expanding range margin under climate change. J Appl Ecol 49:552–561

Lawton JH, Brotherton PNM, Brown VK, Elphick C, Fitter AH, Forshaw J, Haddow RW, Hilborne S, Leafe RN, Mace GM, Southgate MP, Sutherland WJ, Tew TE, Varley J, Wynne GR (2010) Making space for nature: a review of England’s wildlife sites and ecological network. DEFRA, London

Lees AC, Peres CA (2008) Conservation value of remnant riparian forest corridors of varying quality for Amazonian birds and mammals. Conserv Biol 22:439–449

Lin YC, James R, Dolman PM (2007) Conservation of heathland ground beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae): the value of lowland coniferous plantations. Biodivers Conserv 16:1337–1358

Loehle C (2007) Effect of ephemeral stepping stones on metapopulations on fragmented landscapes. Ecol Complex 4:42–47

Lovei GL, Sunderland KD (1996) Ecology and behavior of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Annu Rev Entomol 41:231–256

Luff ML (1998) Provisional atlas of the ground beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae) of Britain. Biological Records Centre, Appots Ripton

Luff ML (2007) The Carabidae (ground beetles) of Britain and Ireland. Royal Entomological Society, St Albans

Marc P, Canard A, Ysnel F (1999) Spiders (Araneae) useful for pest limitation and bioindication. Agric Ecosyst Environ 74:229–273

Marvier M, Kareiva P, Neubert MG (2004) Habitat destruction, fragmentation, and disturbance promote invasion by habitat generalists in a multispecies metapopulation. Risk Anal 24:869–878

McGill BJ, Enquist BJ, Weiher E, Westoby M (2006) Rebuilding community ecology from functional traits. Trends Ecol Evol 21:178–185

Moretti M, Legg C (2009) Combining plant and animal traits to assess community functional responses to disturbance. Ecography 32:299–309

Muff P, Kropf C, Frick H, Nentwig W, Schmidt-Entling MH (2009) Co-existence of divergent communities at natural boundaries: spider (Arachnida: Araneae) diversity across an alpine timberline. Insect Conserv Divers 2:36–44

Nyffeler M, Sunderland KD (2003) Composition, abundance and pest control potential of spider communities in agroecosystems: a comparison of European and US studies. Agric Ecosyst Environ 95:579–612

Ockinger E, Smith HG (2008) Do corridors promote dispersal in grassland butterflies and other insects? Landsc Ecol 23:27–40

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn DJ, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Szoecs E, Wagner H (2018) Vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.5-3. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan. Accessed Dec 2018

Pedley SM, Bertoncelj I, Dolman PM (2013a) The value of the trackway system within a lowland plantation forest for ground-active spiders. J Insect Conserv 17:127–137

Pedley SM, Dolman PM (2014) Multi-taxa trait and functional responses to physical disturbance. J Anim Ecol 83:1542–1552

Pedley SM, Franco AMA, Pankhurst T, Dolman PM (2013b) Physical disturbance enhances ecological networks for heathland biota: a multiple taxa experiment. Biol Conserv 160:173–182

Pedley SM (2012) Effects of experimental disturbance on multi-taxa assemblages and traits: conservation implication in a forest-open landscape mosaic. Doctoral thesis, University of East Anglia, UK

Pedley SM, Dolman P (unpublished) Forestry clear-fell patches benefit heathland arthropods

R Development Core Team (2018) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Rainio J, Niemela J (2003) Ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) as bioindicators. Biodivers Conserv 12:487–506

Ribera I, Doledec S, Downie IS, Foster GN (2001) Effect of land disturbance and stress on species traits of ground beetle assemblages. Ecology 82:1112–1129

Roberts MJ (1987) The spiders of Great Britain and Ireland. Harley Books, Colchester

Roberts MJ (1996) Spiders of Britain and Northern Europe. HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, London

Robinson JV (1981) The effect of architectural variation in habitat on a spider community—an experimental field-study. Ecology 62:73–80

Robinson RA, Sutherland WJ (2002) Post-war changes in arable farming and biodiversity in Great Britain. J Appl Ecol 39:157–176

Roff DA (1990) The evolution of flightlessness in insects. Ecol Monogr 60:389–421

Samu F, Sziranyi A, Kiss B (2003) Foraging in agricultural fields: local 'sit-and-move' strategy scales up to risk-averse habitat use in a wolf spider. Anim Behav 66:939–947

Santini L, Cornulier T, Bullock JM, Palmer SCF, White SM, Hodgson JA, Bocedi G, Travis JMJ (2016) A trait-based approach for predicting species responses to environmental change from sparse data: how well might terrestrial mammals track climate change? Glob Change Biol 22:2415–2424

Schmidt MH, Tscharntke T (2005) Landscape context of sheetweb spider (Araneae: Linyphiidae) abundance in cereal fields. J Biogeogr 32:467–473

Schultz CB (1998) Dispersal behavior and its implications for reserve design in a rare Oregon butterfly. Conserv Biol 12:284–292

Simberloff D, Farr JA, Cox J, Mehlman DW (1992) Movement corridors—conservation bargains or poor investments. Conserv Biol 6:493–504

Smith YCE, Smith DAE, Seymour CL, Thebault E, van Veen FJF (2015) Response of avian diversity to habitat modification can be predicted from life-history traits and ecological attributes. Landscape Ecol 30:1225–1239

Topping CJ, Sunderland KD (1992) Limitations to the use of pitfall traps in ecological-studies exemplified by a study of spiders in a field of winter-wheat. J Appl Ecol 29:485–491

Wamser S, Diekotter T, Boldt L, Wolters V, Dauber J (2012) Trait-specific effects of habitat isolation on carabid species richness and community composition in managed grasslands. Insect Conserv Divers 5:9–18

Wang Y, Naumann U, Wright ST, Warton DI (2012) mvabund—an R package for model-based analysis of multivariate abundance data. Methods Ecol Evol 3:471–474

Webb NR, Hopkins PJ (1984) Invertebrate diversity on fragmented Calluna heathland. J Appl Ecol 21:921–933

Wright LJ, Hoblyn RA, Green RE, Bowden CGR, Mallord JW, Sutherland WJ, Dolman PM (2009) Importance of climatic and environmental change in the demography of a multi-brooded passerine, the woodlark Lullula arborea. J Anim Ecol 78:1191–1202

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Neal Armour-Chelu for logistical help, the Forestry Commission for study permission and Natural England, Elveden Estate, Forest Heath District Council, Norfolk Wildlife Trust, and Suffolk Wildlife Trust for access to heathland sites. Funding was provided by the Natural Environment Research Council, Suffolk Biodiversity Partnership and the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Online Resource 1

Description of species traits (PDF 63 kb)

Online Resource 2

Rarefaction curves for the sampled arthropod communities (PDF 91 kb)

Online Resource 3

Summary of habitat structure variables and vector loadings (PDF 48 kb)

Online Resource 4

Results of Mixed Models (PDF 55 kb)

Online Resource 5

PCoA loadings (PDF 41 kb)

Online Resource 6

Fourth-corner model statistics (PDF 60 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pedley, S.M., Dolman, P.M. Arthropod traits and assemblages differ between core patches, transient stepping-stones and landscape corridors. Landscape Ecol 35, 937–952 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-00991-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-00991-0