Abstract

Context

Transportation and wildlife agencies may consider the need for barrier structures and safe wildlife road-crossings to maintain the long-term viability of wildlife populations. In order to prioritize these efforts, it is important to identify species that are most at risk of extirpation from road-related impacts.

Purpose

Our goal was to identify reptiles and amphibians in California most susceptible to road mortality and fragmentation. With over 160 species and a lack of species-specific research data, we developed an objective risk assessment method based upon road ecology science.

Methods

Risk scoring was based upon a suite of life history and space-use characteristics associated with negative road effects applied in a hierarchical manner from individuals to species. We evaluated risk to both aquatic and terrestrial connectivity and calculated buffer distances to encompass 95% of population-level movements. We ranked species into five relative categories of road-related risk (very-high to very-low) based upon 20% increments of all species scores.

Results

All chelonids, 72% of snakes, 50% of anurans, 18% of lizards and 17% of salamander species in California were ranked at high or very-high risk from negative road impacts. Results were largely consistent with local and global scientific literature in identifying high risk species and groups.

Conclusions

This comparative risk assessment method provides a science-based framework to identify species most susceptible to negative road impacts. The results can inform regional-scale road mitigation planning and prioritization efforts and threat assessments for special-status species. We believe this approach is applicable to numerous landscapes and taxonomic groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There have been many attempts to better characterize and quantify threat criteria in order to classify species at higher risk of extinction at state, national, and global levels (Congress 1973 (U.S. Endangered Species Act); Mace et al. 2008; Hobday et al. 2011; Thomson et al. 2016; IUCN 2017). Roads are a significant threat to wildlife populations (e.g., Forman et al. 2003; Andrews et al. 2015a; van der Ree et al. 2015), causing both barrier (habitat fragmentation) and depletion (road mortality) effects. Barrier effects occur when animals avoid crossing roads, in which case roads essentially fragment species habitat. Barrier effects include reduced size and quality of available habitat, reduced effective population size, reduced ability to find mates and resources, increased genetic structuring, and increased probability of local extirpation (e.g., Forman et al. 2003; Fahrig and Rytwinski 2009; D’Amico et al. 2016). Depletion effects occur when animals attempt to cross roads and are killed by vehicles. Depletion effects include all of the risks from barrier effects as well as reduced survivorship, making high road mortality an even greater concern (Jackson and Fahrig 2011). Among other stressors, such as habitat loss and fragmentation, invasive species, pesticide use, changing climate, and disease, the negative impacts from roads may independently or cumulatively threaten the persistence of populations and even species.

Amphibians and reptiles have been identified as being particularly susceptible to the negative effects of roads within their habitat (e.g., Klauber 1931; Forman et al. 2003; Rytwinski and Fahrig 2012; Andrews et al. 2015a, b; D’Amico et al. 2015). Many are slow moving, do not avoid roads, and are simply too small for drivers to see and avoid. During rains many amphibians make long linear terrestrial movements regardless of the presence of intersecting roadways (Glista et al. 2008), and because paved roads typically absorb and retain more heat than the surrounding habitat, snakes and lizards are often attracted to roads for thermoregulation (Case and Fisher 2001; Jochimsen et al. 2004). In fact, road surveys are one of the most common methods for surveying these reptiles (e.g., Sullivan 2012). Many herpetofauna species utilize both aquatic and terrestrial habitat for breeding, development, foraging, and overwintering and therefore require connectivity within and between both aquatic and terrestrial habitats to support basic life history requirements.

The primary goal of this study was to provide information to transportation and other planning agencies in California to assist them in prioritizing road mitigation efforts for amphibian and reptile species. Although there is still a lot to learn about the effectiveness of different designs of road mitigation systems, the use of barrier systems, underpasses, and overpasses can reduce road mortality and help to maintain connectivity and safe passage across roads for herpetofauna and other wildlife (Jochimsen et al. 2004; Colino-Rabanal and Lizana 2012; Langton 2015; Langen et al. 2015b). Because it is currently unrealistic and cost prohibitive to mitigate all roadways for all species, it is vital to identify species most susceptible to road-related impacts. Within species ranges, risks to populations and need for mitigation can then be evaluated based upon local road densities and matrix, road-types, traffic, and road locations in relation to species habitat and movement corridors (e.g., Jaeger 2000; Litvaitis and Tash 2008; Langen et al. 2015b; Zimmermann Teixeira et al. 2017).

Here we describe a road risk assessment methodology applied to native amphibian and reptile species in California, a global biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al. 2000). We also included analysis of subspecies if they had special federal or state protection status. This includes 166 species and subspecies of frogs, toads, salamanders, snakes, lizards, turtles, and tortoise. Rankings and prioritizations such as these can be very subjective. In order to avoid including low risk species that may be favored by the assessors or to unintentionally overlook species that are at high risk, it was important for this be done in an objective manner informed by current road ecology literature.

Very few quantitative data are available on the impact of roads on population persistence. Jaeger et al. (2005) were the first to develop a relative ranking system to compare the impact of roads on wildlife populations. Their ranking system was largely based upon behavioral responses of animal species to the road surface, road size, traffic noise, and vehicles with varying road sizes and traffic volumes. However, knowledge of these detailed behavioral responses to ranges in road and traffic characteristics is rarely found in literature and the link between individual behavior and population-level effects has not been clearly established (Rytwinski and Fahrig 2012, 2013).

Rytwinski and Fahrig (2012) performed a meta-analysis of wildlife groups to test whether certain life history characteristics were related to negative responses to roads. High reproductive rate (fecundity) was negatively associated with the magnitude of population-level effects for amphibians. No associations were significant in reptiles, although there were few studies to inform this analysis. However, a strong link was shown between body size, greater mobility, lower reproductive rates and the magnitude of negative road effects in mammals, the most studied wildlife group. Conversely, simulations predicted populations of species with small home ranges and high reproductive rates were the least likely to be affected by roads (Rytwinski and Fahrig 2013).

We used these findings as a basis for creating a multi-tiered system to rank and identify reptile and amphibian species that may be most susceptible to road impacts. We based our ranking upon a suite of species life history and space-use characteristics associated with negative road effects, as well as including species distribution and conservation status. We evaluated risk to both aquatic and terrestrial connectivity and include buffer distances that were calculated to encompass 95% of population movements. Relative confidence in these distances is given for each species based upon the amount of support from scientific studies. We solely focused on the direct effects of roads as barriers and sources of road mortality and not impacts from road construction and maintenance or indirect effects from increased human use of the landscape once a road is in place (see review by Langen et al. 2015a).

Because we based the risk assessment solely upon space-use and life history characteristics, this represents a species relative susceptibility to road impacts. It is understood that circumstances associated with particular populations (e.g., local road types, locations, densities) may elevate or reduce the risk for certain populations and species.

Methods

Road risk assessment (overview)

We assessed the relative risk of California herpetofauna species to negative road-related impacts at three scales in a hierarchical fashion. We first assessed risk at the scale of an individual animal and then expanded the risk to the population and then to species (Fig. 1).

California reptile and amphibian road risk assessment conceptual model (ARSSC Amphibian and Reptile Species of Special Concern (Thomson et al. 2016))

At the individual-level, we based road risk primarily upon the likelihood that an individual would encounter one or more roads. We considered this a product of movement distance (home range, seasonal migrations) and movement frequency (e.g., active foragers, seasonal migrants, sit-and-wait predators vs. sedentary species) (e.g., Bonnet et al. 1999; Carr and Fahrig 2001). Because many species are semi-aquatic, movement distance and frequency were scored separately for both aquatic and terrestrial habitats.

There is a theorized higher risk associated with depletion effects (i.e., road mortality) in comparison to barrier effects (Fahrig and Rytwinski 2009; Jackson and Fahrig 2011). Therefore, we gave additional weight to those species more likely to go out onto a road surface and be killed by vehicular traffic. For this we considered factors of habitat preference (e.g., open vs. closed), roads as potential attractants (e.g., for basking), and movement speed (e.g., slow vs. fast). However, individuals within and among species may respond differently to roads (attraction vs. avoidance) based upon local landscape features, road width, traffic volume, and perceived danger (Forman et al. 2003; Andrews 2005; Brehme et al. 2013; Jacobson et al. 2016). Because a state-wide analysis encompasses extreme variation in landscape and road characteristics, the extent to which roads act as barriers or sources of direct mortality within a species range is unknown. The risk disparity between depletion and barrier effects could also be highly variable. Therefore, we limited the additional weight for potential depletion effects to twenty percent of the individual risk score.

We assessed population-level road risk by multiplying individual risk with scores representing: (1) the relative proportion of the population at risk; and (2) the species ability to sustain higher rates of mortality. For instance, the proportion of the population at risk was expected to be higher for migratory species than for territorial species. Highly fecund species were expected to better withstand (or more quickly recover from) higher mortality in comparison to those with few annual offspring.

Finally, we assessed species-level road risk by multiplying population road risk with scores for range size (both within and outside of California) and conservation status according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS 2016) and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW 2016a; Thomson et al. 2016). Species with smaller ranges typically have fewer populations and are thus less resilient to population-level stressors. Endangered, threatened, and special concern species have already been designated at risk of extirpation, often due to multiple stressors, and are thus thought to be less likely to be resilient to additional road impacts.

Although we present both aquatic and terrestrial risk scores for semi-aquatic species, we used the higher of the two scores for the overall risk ranking.

Literature review

Species life history data were primarily taken from and cross-checked among the following species account review sources;

-

1.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Recovery Plans and 5-year Reviews https://www.fws.gov/endangered/.

-

2.

California Amphibian and Reptile Species of Special Concern (ARSSC; Thomson et al. 2016).

-

3.

A Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California (Stebbins and McGinnis 2012)

-

4.

Amphibian declines: the conservation status of United States species (Lannoo 2005).

-

5.

Conservation Status of Amphibians and Reptiles on USDA National Forests, Pacific Southwest Region, 2012 (Evelyn and Sweet 2012).

-

6.

Natureserve Explorer (natureserve.org): Species Accounts largely authored by G. Hammerson (2003–2016).

When these reviews were lacking life history information needed for the road risk assessment, we then searched for supplementary peer-reviewed literature using the Google Scholar search engine. Because movement distances (terrestrial, aquatic, home range, migratory) were so important for the risk assessment, we acquired referenced articles from the species accounts and independently searched the literature to acquire these data. Search terms included the species common name, scientific name, or genus and terms such as “movement”, “home-range”, “spatial”, and “telemetry”. We also reviewed articles for citations of other studies to find more recent information on movement. This literature included published articles, book chapters, M.S. Theses, Ph.D. dissertations, agency reports, and consultant reports. In the case that specific life history or movement information was not found for a species, we chose a surrogate species based upon phylogeny, habitat, and body size. We first looked for the closest related species within the genus or family and chose a closely related surrogate based upon similar habitat and body size. If surrogates were used, these are clearly reported.

Road risk metrics

The following section describes in detail the rank scoring used for Individual-level Road Risk, Population-level Road Risk, and Species-level Road Risk. All rank values are meant to represent the relative contribution of each attribute to either additive or multiplicative road risk.

Individual-level risk (100 points possible)

Out of a total of 100 points for individual road mortality risk, we attributed up to 80 points (80%) to the risk of encountering a road and up to 20 points (20%) for the risk of an individual moving onto a road and being killed by a motor vehicle.

The risk of encountering a road was based on a combination of movement distance and general movement frequency. Movement distance was ranked 1–40 based upon home range movement distances (diameter) for non-migrants or migration distances for seasonal migrants that spanned from 0 to > 1200 m (Table 1). The scores are linearly correlated with increasing movement distance.

For species that use both terrestrial and wetland/stream/riverine habitats, such as frogs, toads, aquatic snakes and turtles, we scored aquatic and terrestrial movement distances and frequencies separately. This was necessary as some species move much larger distances and at different frequencies in one habitat versus the other. This also informs the type(s) of mitigation structures that may be warranted based upon habitat type, buffer distances and risk scores for each species. Aquatic movement distances were not calculated for pond-breeding amphibians. Ponds are typically small ephemeral bodies of water and terrestrial movements of amphibians to and among ponds account for the majority of movement for these species.

The calculations and rankings for movement distances were well considered and deserve further explanation. Our original thinking was that maximum distances should reflect relative movement distances across species and these data were commonly reported in species accounts. However, it became increasingly difficult to determine whether maximum distances reported were seasonal migration movements, home range movements or rarer dispersal events. We believed this assessment should reflect annual movement distances and not rare dispersal events. We considered using average/median movement distances; however, these often underestimate the movement of seasonal migrants because in many cases a sizeable portion of the population may remain close to a breeding site, while another sizable portion make longer distance migrations causing an average or median to be uninformative. Therefore, we decided to use a buffer distance that incorporates the movement distances of 95% of the population studied. A 95% population movement distance is commonly accepted for the delineation of terrestrial buffer zones for amphibians (i.e., Semlitsch 1998; Semlitsch and Bodie 2003) and we believe it was the most biologically meaningful and useful measure for this study. This measure, which we will refer to as Maximum Population Movement Distance (MPMD), should include almost all population movements, such as seasonal migration distances and annual home ranges (diameter), but not rare dispersal events. The MPMD should also be useful for local risk assessments as these distances can be used to aide in mapping and mitigation decisions.

The calculation we used for MPMD is commonly known as the 95% upper tolerance interval (Vangel 2015). A tolerance interval is an interval that is meant to contain a specified percentage of individual population measurements. This should not be confused with a confidence interval, which is an interval that is meant to contain the population mean. We chose a 50% confidence level for the upper 95% confidence limit of movement distances which is equal to the 95% prediction interval for future observations and is the mean + 1.645 × standard deviation. In cases where a standard deviation was not reported, we back calculated standard deviation from the standard error and sample size, calculated it from the individual data, or estimated it based on the methods recommended by Hozo et al. (2005). Although non-parametric tolerance intervals would be more appropriate for non-normally distributed movement data, the data required to calculate these is rarely reported in the published literature. In the case of non-normally distributed data where medians, sample sizes and ranges are reported, Hozo et al. (2005) methods allow for approximation of means and standard deviations with no assumption of the underlying data distribution. We found the resulting MPMDs to be reasonable in excluding large outliers but including multiple long distance movements below the maximum movement distance.

We recognize that for any species there can be substantial variability in movement distances that depend upon varying local, landscape, and climatic factors. This was often reflected in studies with sometimes widely varying estimates of home range and migration distances. We attempted to be conservative by using the study data for calculation of MPMD in which the largest population movement distances were observed. For studies where movement distance significantly varied between females and males, we used the information from the wider ranging sex. For migratory distances, we did not use distances from extreme environments, such as Canada, where suitable overwintering sites are typically much farther away from breeding and summer activity areas than in milder California climates (e.g., Gregory 1984). We did use study data from adjacent states or lower estimates of migration distances from those reported in Midwestern states. In some cases where little information was available, we made an educated guess based upon limited study data and/or closely related species and noted these in the tables. For all MPMDs, we report a relative confidence level based upon the number and quality of studies, sample sizes, and locations in or adjacent to California. It is intended that the scores be adjusted as new information becomes available.

To compute the risk of encountering a road, the MPMD was multiplied by a relative index of the expected frequency of longer distance movements (1–2 points; Table 1). We defined three frequency categories largely based upon annual migratory movements or foraging strategies for non-migratory species. The highest category included actively foraging predators which are characterized by frequent wandering movements throughout their home range (Pianka 1966). Less frequent movers included seasonal migrants traveling among breeding, summer foraging, and/or overwintering sites and non-migratory ‘sit-and-wait’ predators that remain still for long periods of time to ambush prey (Pianka 1966). Finally, low frequency included highly sedentary species with high site fidelity, particularly specialized rock, crevice, soil, or tree dwellers that may rarely traverse terrestrial or aquatic habitats.

The risk of an individual moving onto a road and being killed by a moving vehicle was ranked by attributes of habitat preference, road use, and movement speed (Table 2). Habitat preference represents the degree to which an individual is expected to go out onto or avoid an open road as predicted from their habitat and microhabitat preferences. Open habitat specialists and generalists were expected to more readily move onto a road than species that prefer cover (e.g., Forman et al. 2003; Brehme et al. 2013). Although many amphibians are closed habitat specialists, most readily move through open habitats during rain events, when most overland migratory movements tend to occur (Glista et al. 2008). Therefore, amphibians were considered open habitat specialists for this ranking. An additional factor that may increase road use is for thermoregulation for lizards and snakes, as roads often retain more heat than the surrounding environment (Colino-Rabanal and Lizana 2012; Mccardle and Fontenot 2016). Finally, there is an increased risk of road mortality for slow versus fast moving species (see Andrews and Gibbons 2005; Mazerolle et al. 2005; Andrews et al. 2015b).

Population-level Road Risk (400 points possible)

To assess the risk of negative road impacts on the persistence of a population we incorporated scores for population-level movement behavior and fecundity (Table 3). For the proportion of a population expected to encounter a road, we scored the greatest risk to species that seasonally migrate to overwintering and breeding areas (Jackson et al. 2015). For those that do not migrate, we expected higher proportions of non-territorial or loosely territorial species (“wandering”) to encounter roads than species that defend distinct territories.

Species with low fecundity are less resilient to road mortality impacts than highly fecund species (Rytwinski and Fahrig 2013). Relative fecundity was simply calculated from the average number of potential offspring per year whether the animals were oviparous or live-bearing. For egg-laying species, the number of potential offspring was calculated by multiplying the average clutch size by the average number of clutches per year.

Individual mortality risk (1–100 points) was multiplied by the sum of these population-level factors (1–4 points) to calculate population-level road risk.

Species-level road risk (1200 points possible)

In comparison to population-level risk, we considered the overall risk of roads to species to be negatively associated with species range and conservation status. Although some populations may be at high risk, species with a wide distribution and many populations should be more resilient to localized declines and extirpations. Therefore, we assigned a range isolation score ranging from 0 to 1 that considered species distributions range-wide (North America) and within California (CA) (Table 4). Range-wide distribution varied from “CA only” to “widespread” (> 4 states). If the species range extended into Mexico and/or Canada, these countries were counted as another state for calculation of the index. California-wide distribution was calculated based upon the number of CA geographic regions occupied out of twelve regions defined by Hickman (1993) and used in Stebbins and McGinnis (2012). These two scores (Range-wide isolation, CA isolation) were summed and divided by two in order to normalize the overall range isolation score to a 0 to 1 scale.

At the species-level, we also incorporated conservation status (Table 4). Some species are declining and are at higher risk of extinction often due to multiple stressors. Federal and State Threatened and Endangered Species were given the highest score (1.0). In California, forty-five species are designated “Species of Special Concern (SSC)” with a ranking of 1, 2, or 3 based upon severity and immediacy of threats affecting each taxon (Thomson et al. 2016). SSC species were given a conservation status score ranging from 0.25 to 0.75 based upon their SSC ranking. Population-level Road Risk (score range 1–400) was multiplied by (1 + Range Isolation Score + Conservation Status Score; score range 1–3) to calculate the final Species-level Road Risk.

Range and conservation status were only used as a multiplier for species-level road risk if the population-level road risk was greater than 80 (20% of possible population score). This helped to prevent false inflation of the road risk metrics for low road susceptible species.

Because all members of the genus Batrachoseps (slender salamanders) are similar in body size, range size and general life history characteristics, we scored the genus as whole with the most conservative estimates and conservation status but included all 20 species in the final count and calculations.

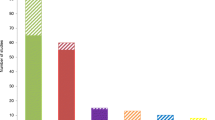

Once all 166 species (including subspecies with conservation status) were scored for species-level road risk within both terrestrial and aquatic habitats, we took the maximum score for each species and sorted them from the highest to lowest scores. We grouped species into categories of risk (Very high, high, medium, low, and very low) based upon ranges of values that represented frequency distributions in 20% increments of all species scores (Table 5, Fig. 2).

As a way to support the results of our ranking model with species literature, we focused on special status species. We reviewed recovery plans and 5-year reviews for federally listed species and state species accounts for California listed species and species of special concern (collectively referred to as special status species). For each rank group (i.e., “very low” to “very high”), we calculated the percentage of special status species where roads were specifically listed as a threat. Similarly, we tallied the number of species identified in a recent California preliminary road risk assessment (Levine 2013, Amy Golden pers. comm.) and compared the number of species that fell within each of our road risk categories.

Results

All chelonids, 72% of snakes, 50% of anurans, 18% of lizards and 17% of salamander species were ranked as high or very high risk from negative road impacts. (Table 6, Fig. 3).

Review of species accounts, recovery plans, and 5-year reviews for all special status species showed that 94% (17/18) of species accounts that referenced roads as a threat to the species were ranked as “high” or “very high” in our risk assessment (Table 7). Of the special status species that ranked ‘high’ and ‘very high’, close to fifty percent (17/35) had road-related threats referenced in their listing literature. In comparison, only 4% (1/27) of ‘medium’ to ‘very low’ risk special status species accounts mentioned roads as a potential threat. In addition, 79% (15/19) of species of concern recommended in a recent Caltrans preliminary road risk assessment scored as ‘high’ or ‘very high’ risk in our analysis (Levine 2013, Amy Golden pers. comm.).

Risk scores and relative rankings for California reptile and amphibian species in both terrestrial and aquatic habitats are presented in Tables 8. Terrestrial and Aquatic rankings are provided separately in Tables 9 and 10 and also include population-level risk scores, 95% population buffer distances, confidence levels, and identification of any surrogate species used for the distance calculations. Species scores for all ranking criteria and life history and movement references are provided in Appendices 1 and 2.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to objectively assess the relative risk of roads at a species level using a logical and scientifically based framework and apply it across a large array of species and habitats. We believe this approach could be useful for assessing and comparing susceptibility of species to negative road impacts within and among all taxonomic groups. To date, such risk assessments have been based largely upon expert opinion, limited information available on road mortality, and even less information available on population or species-level road effects (Levine 2013; Rytwinski and Fahrig 2015).

Overall, this is meant to be a first step in highlighting reptile and amphibian species that may be at highest risk from roads transecting their habitat. These species may deserve consideration for further study and for implementing mitigation solutions to reduce mortality and to maintain or enhance connectivity. The risk assessment was done for both terrestrial and aquatic habitats to further inform mitigation. Some aquatic species may greatly benefit from fish passages while others may better benefit from terrestrial barriers and wildlife crossings or both.

Although data are currently lacking to validate completely the scoring and results of the risk assessment, our review of species accounts, recovery plans, 5-year reviews for federal and state-listed species and California species of special concern show a strong association between elevated road risk from our objective analysis and the probability that roads are listed as a potential threat to the species in the species listing literature.

Although more than 40% of special status species are semi-aquatic, roads were rarely considered a threat to aquatic connectivity in the species literature. This may be accurate if bridges or large culverts currently exist for water flow that also provide permeability to aquatic movement. Bridges are generally considered to be completely passable by all aquatic species. Bridges are more likely to be constructed adjacent to or over large water bodies and rivers, presumably resulting in less risk to aquatic movement of populations that inhabit lake and river systems. However, culverts that are more commonly constructed under roads in streams and wetlands vary in passability depending on factors such as diameter, length, slope, outlet configuration, and other characteristics (Furniss et al. 1991; Clarkin et al. 2005; Kemp and O’Hanley 2010). In fact, Januchowski-Hartley et al. (2013) found that only 36% of road crossings were fully passable to fish in the Great Lakes basin. In addition, many low water crossings in arid regions of the state are simply a dip in the road that allows water to flow over the surface during high flow events. These may be used as road crossings by species traveling along ephemeral stream corridors with or without water flow. Given these potential vulnerabilities, we believe that road impacts to aquatic connectivity of herpetofauna deserve greater consideration.

Across broad taxonomic groups, chelonids (tortoises/turtles) and snakes had the greatest percentages of species at ‘high’ or ‘very high’ risk from roads. They are similar in that many move long distances (home range and/or migratory), tend not to avoid roads (or are attracted to them for thermoregulation), are long lived, and have relatively low fecundity in comparison to other herpetofaunal groups. Because of these traits, chelonids and snakes have been identified elsewhere as being particularly susceptible to negative population effects from roads (Gibbs and Shriver 2002; Andrews et al. 2015b; Jackson et al. 2015).

There are only four species of chelonids in California, (desert tortoise (Gopherus agazzii), Northwestern pond turtle (Actinemys marmorata), Southwestern pond turtle (Actinemys pallida), and the Sonoran mud turtle (Kinosternon sonoriense)). There has been a high level of attention to road impacts on the desert tortoise (Gopherus agazzii) as numerous studies have documented not only high road mortality, but measurable road effect zones, and mostly positive responses to barriers and underpasses (e.g., Boarman and Sazaki 1996, 2006; Peaden et al. 2016; but see Peadon et al. 2017). Although not listed as a primary threat to pond turtle populations in California (Thomson et al. 2016), road mortality is a major concern for western pond turtle populations in Oregon (Rosenberg et al. 2009). Pond turtles travel kilometers within perennial waters and from pool to pool in intermittent aquatic habitats to forage and find mates (Goodman and Stewart 2000). In addition, females nest and lay eggs in terrestrial habitats up to 0.5 km away from water which make roads that parallel aquatic habitat a threat to both females and hatchlings (Reese and Welsh 1997; Rathbun et al. 2002; Pilliod et al. 2013). In fact, road mortality of females has been identified as a cause for male-biased sex ratios in some populations of pond turtles and other freshwater turtle species (Steen et al. 2006; Rosenberg et al. 2009; Reid and Peery 2014). Therefore, this species requires consideration of both aquatic and terrestrial connectivity to satisfy their annual resource requirements. Sonoran mud turtles also travel long distances within intermittent streams and thus may be at risk of roads that transect their aquatic habitat (Hensley et al. 2010).

Larger colubrid snakes (Family Colubridae; many genera) and rattlesnakes (genus Crotalus) were ranked among the highest risk from negative road effects. In addition to being attracted to paved road surfaces for thermoregulation, many large snakes have wide home-ranges or may move large distances between winter hibernacula and summer foraging areas. In contrast to smaller species, larger snakes are also less likely to avoid roads (Rosen and Lowe 1994; Andrews and Gibbons 2005; Andrews et al. 2008; Siers et al. 2016). High road mortality (e.g., Klauber 1931; Rosen and Lowe 1994; Jones et al. 2011), reduced abundance near roads (Rudolph et al. 1999; Jones et al. 2011), increased extinction risk (Row et al. 2007), and decreased genetic diversity (Clark et al. 2010; Hermann et al. 2017) have been documented for numerous snake species; as have positive responses to barriers and underpasses (Dodd et al. 2004; Colley et al. 2017). In our statewide risk analysis, coachwhips (genus Masticophis/Coluber) were amongst the highest risk groups at both the population and species-levels. These are particularly wide-ranging and very active foragers in comparison to other snake genera (Stebbins and McGinnis 2012). The coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum) was found to be ninefold more likely to be extirpated from habitats that were fragmented by roads and urbanization, contributing to their decline throughout California (Case and Fisher 2001; Mitrovich 2006). Similarly, habitat fragmentation from roads and urbanization were identified as primary threats to the Alameda whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus USFWS 2011). Although road use and mortality have been documented for many other terrestrial California snake species on road-riding surveys (e.g., Klauber 1931; Jones et al. 2011; Shilling and Waetjen 2017), there is a paucity of studies examining population-level effects of roads on California snake species. We could find only one such study, where presence of a highway was shown to reduce gene flow in the Western diamond-backed rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) in the Sonoran Desert, AZ (Hermann et al. 2017).

Long foraging movements within aquatic habitats also contributed to the majority of garter snakes (genus: Thamnophis) falling within the highest road risk categories. Maintaining aquatic and wetland connectivity is of primary concern for these species. Garter snakes also use terrestrial habitats for overwintering, reproduction, and for moving among wetland or aquatic patches. Some migrate long distances to winter hibernacula, making them also susceptible to roads within adjacent terrestrial habitats (Roe et al. 2006; Jackson et al. 2015). The highly aquatic giant garter snake (Thamnophis gigas) had the highest aquatic road risk score. Because it moves only short distances on land (Halstead et al. 2015), mitigation may best focus on functional aquatic passages with lengths of adjacent road barriers based upon their terrestrial movement distances.

Toads were the third highest ranking group with 64% ranked in the highest risk categories. In particular, Bufonid toads (family Bufonidae) may move large distances (> 1 km) in both aquatic and terrestrial habitats to satisfy their annual resource requirements; thus 5 of 7 bufonid species ranked high or very high risk from roads. Consistent with our risk assessment results, there is evidence that bufonid toads are particularly susceptible to negative impacts from roads elsewhere (Trenham et al. 2003; Orłowski 2007; Eigenbrod et al. 2008).

Roads and traffic have been associated with reduced abundance and species richness of frog populations (e.g., Fahrig et al. 1995; Houlahan and Findlay 2003). However, approximately half of California species are small, primarily aquatic, highly fecund, with relatively limited movements and thus ranked low for road impacts. Four of 11 species ranked within the highest risk groupings; California red-legged frog (Rana draytonii), Oregon spotted frog (R. pretiosa), Northern red-legged frog (R. aurora), and Cascades frog (R. cascadae). The Oregon spotted frog (R. pretiosa) is known to move large distances within aquatic habitats (Bourque 2008; USFWS 2009). Construction of a highway that bisected the Yellowstone population of Oregon spotted frogs was one important factor that reduced the population dramatically in the 1950s (see discussion in Watson et al. 2003). Although portions of the populations show high site fidelity, California red-legged frog and Northern red-legged frog migrants can move large distances (> 1 km) across both aquatic and terrestrial habitats (Bulger et al. 2003; Fellers and Kleeman 2007; Hayes et al. 2007). Road mortality or habitat fragmentation from roads and urbanization were listed as primary threats to these species elsewhere (USFWS 2002; COSEWIC 2015).

Lizards had relatively low percentages of species in the high risk groupings. Many lizard species are small, non-migratory, territorial, have small home ranges and are thus at low risk of negative road effects. Similar to snakes, lizards can also be attracted to road surfaces for thermoregulation. A few wide ranging species scored in the highest risk categories including the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), leopard lizards (genus Gambelia) and two horned lizard species (genus Phrynosoma). The Gila monster has been negatively associated with urbanization, where larger home ranges and greater movement rates result in higher mortality for males (Kwiatkowski et al. 2008). Sensitive to habitat fragmentation, the blunt-nosed leopard lizard (Gambelia sila) was found to be largely absent from habitat patches less than 250 ha (Bailey and Germano 2015). Flat-tailed horned lizards (Phrynosoma mccallii) are also susceptible to habitat fragmentation with very large home ranges for their size, particularly in wet years (Young and Young 2000). In fact, road mortality is a well-known threat for this species (see review by CDFW 2016b). Horned lizards are also particularly vulnerable to being killed on roads due to their tendency to flatten and remain motionless while being approached (Young and Young 2000).

Salamanders also had relatively low percentages of species in the high risk grouping. Over 75% (35/46) of the California salamanders are lungless salamanders (Plethodontidae) and Torrent salamanders (Rhyacotritonidae). These species are mostly small, sedentary, non-migratory, closed habitat specialists with limited movement distances and these traits have resulted in a high level of speciation. This is exemplified by there being at least 20 species of slender salamanders (genus Batrachoseps) in California alone (Martinez-Solano et al. 2007; Vences and Wake 2007). However, within the salamander group, newts and several other migratory salamander species were ranked within the highest risk categories from negative road effects. There is substantial evidence that habitat fragmentation and mortality due to roads negatively affect many of these species. For instance, newts regularly migrate long distances over land from and to breeding ponds, and to terrestrial foraging habitats (> 2 km; Trenham 1998). Large numbers are found dead on roads during dispersal periods and newt species are often the first to disappear in fragmented landscapes (Gibbs 1998; Trenham 1998, Shields pers. comm.). Similarly, road mortality and habitat fragmentation are primary threats to the California tiger salamander and other Ambystomid salamanders because terrestrial habitat is used for interpond migration and overwintering (Semlitsch 1998; Trenham et al. 2001; Bolster 2010).

Because this assessment covers a wide array of species and habitats, the risk to particular species populations must be re-assessed on a local level. This includes consideration of the locations, types, and densities of roads in relation to population and species ranges along with goals for functional, meta-population, and genetic connectivity (e.g., Marsh and Jaeger 2015). Due to very low road densities in their limited ranges, some species and populations may be at lower risk. For instance the Gila monster, Oregon spotted frog, Sonoran mud turtle, Sonoran desert toad (Incilius alvarius) and Yosemite toad (Anaxyrus canorus) scored high due to life history and space-use characteristics, however their limited ranges are largely in protected or low road density areas in the state. Thus roads may not be a significant threat to these species in California. In contrast, high road densities may increase the risk for species within coastal regions such as remaining populations of Santa Cruz long-toed salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum), Alameda striped racer (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus), and San Francisco garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia). However, most species consist of numerous populations with a myriad of differing road-related threat levels. Although detailed species ranges and occupancy within ranges are well known for some species with very limited ranges, for most species range-wide surveys have not been conducted. Therefore, only general range boundaries are available that encompass large portions of the state and availability of species distribution models of habitat suitability and occupancy within their ranges is rare. This lack of detailed spatial information on species distribution further limits the potential to incorporate road locations, types, and densities in a state and species-wide assessment.

We also note that relative risk to negative road impacts is provided for both populations and species. Risk was elevated for species with small and isolated ranges and that are facing a myriad of other threats. Because of this, a few common widespread species scored high at the population-level but not at the species-level. This included gopher snakes (Pituophis catenifer) and western toads (Anaxyrus boreas) where road mortality has been identified as a threat to the persistence of local populations (e.g., COSEWIC 2012; Jochimsen et al. 2014).

To potentially aid in local assessments, we have provided distance estimates or “buffer zones” that contain estimates for 95% of population-level movements for all species (e.g., Semlitsch and Bodie 2003). We provide all references evaluated for distance estimates in Appendix 2. Meta-population movements can be very important to the stability of pond-breeding amphibians (e.g., Semlitsch 2008; Jackson et al. 2015) and are included in many of the buffer zone calculations. However, we note that buffer zones may not include meta-population-level movements if the rate of these dispersal movements was less than 5% in the studies we used for our analyses.

This should be considered an initial assessment of susceptibility to negative road impacts in a hierarchical framework (e.g., see Level 2; Hobday et al. 2011). Therefore, as previously stated it will be important to re-assess the risk of specific populations to roads within their habitat and to evaluate and compare alternatives at the local scale (e.g., Suter 2016). This may include more detailed information on specific road attributes (e.g., density, type, location), as well as species behavior (Jaeger et al. 2005; Rouse et al. 2011; Rytwinski and Fahrig 2013; Jacobson et al. 2016). Age structured and spatially explicit population viability models are valuable tools to predict long-term population responses to roads and to compare outcomes of multiple mitigation scenarios (e.g., Gibbs and Shriver 2005; Borda-de-Água et al. 2014; Polak et al. 2014; Crawford 2015). Need and placement of mitigation structures can be guided by local population or meta-population dynamics, landscape attributes, movement routes, and road mortality hot spots (e.g., Bissonette and Adair 2008; Langen et al. 2009, 2015b; D’Amico et al. 2016; Loraamm and Downs 2016).

The quantity and quality of life history information, particularly movement data, are highly variable among species (see confidence levels; Tables 9 and 10). Therefore it is important to re-assess risk as new information becomes available. Finally, this is a structured assessment of comparative risk across a range of target species; therefore specific values for high risk have not been established. The ranking or assessment methodology should be adaptive and updated with advancements of road ecology science (e.g., Linkov et al. 2006).

Conclusion

Although roads are a significant cause of mortality and habitat fragmentation for many wildlife populations, road-related risk rankings have been based largely on expert opinion due to a scarcity of literature on road effects for most species. Therefore, we developed an objective and scientifically-based comparative risk approach to assess the potential threat from negative road impacts using species life history and movement data. After applying it to over 160 herpetofaunal species (and subspecies) in the state of California, the results are consistent with road ecology literature in identifying known high risk species, and call attention to some species not previously identified. Overall, we found that snakes and chelonids had the largest proportion of species at high risk for negative road impacts due to longer movement distances (home range and/or migratory), lack of road avoidance, and relatively low fecundity in comparison to other herpetofaunal groups. Results also indicated that consideration of aquatic connectivity appears to be under-represented for semi-aquatic herpetofauna that use both terrestrial and stream, riverine, or wetland habitats.

In addition to informing transportation planning and mitigation considerations for California herpetofauna, we believe this approach may be useful for comparing the risk of road-related fragmentation and mortality for species elsewhere and for other taxonomic groups. The results can help to inform multi-criteria threat assessments for special status species or those in consideration for listing. Finally, this serves to highlight species that may deserve further study and consideration for aquatic and terrestrial road mitigation to reduce mortality and to maintain population-level connectivity.

This risk assessment approach compares the susceptibility of species to negative road impacts. Commonly, there are numerous populations within a species range that occupy areas with greatly differing road pressures. Therefore, the actual risk to specific species populations will depend upon local road densities, road-types, traffic, and road locations in relation to species habitat and movement corridors.

References

Andrews KM, Gibbons JW (2005) How do highways influence snake movement? Behavioral responses to roads and vehicles. Copeia 4:772–782

Andrews KM, Gibbons JW, Jochimsen D, Mitchell J (2008) Ecological effects of roads on amphibians and reptiles: a literature review. In: Mitchell JC, Jung Brown RE, Bartholomew B (eds) Urban Herpetology, Herpetological Conservation 3. Society for the Study of Reptiles and Amphibians, Salt-Lake City, UT, pp 121–143

Andrews KM, Nanjappa P, Riley SP (eds) (2015a) Roads and ecological infrastructure: concepts and applications for small animals. JHU Press, Baltimore, MD

Andrews KM, Langen TA, Struijk RPJH (2015b) Reptiles: Overlooked but often at risk from roads. Handbook of Road Ecology. Wiley, New York, pp 271–280

Bailey CV, Germano DJ (2015) Probability of occupancy of blunt-nosed leopard lizards on habitat patches of various sizes in the San Joaquin Desert of California. W Wild 2:23–28

Bissonette JA, Adair W (2008) Restoring habitat permeability to roaded landscapes with isometrically-scaled wildlife crossings. Biol Conserv 141(2):482–488

Boarman WI, Sazaki M (1996) Highway mortality in desert tortoises and small vertebrates: success of barrier fences and culverts (No. FHWA-PD-96-041)

Boarman WI, Sazaki M (2006) A highway’s road-effect zone for desert tortoises (Gopherus agassizii). J Arid Environ 65(1):94–101

Bolster BC (2010) A status review of the California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense). Report to the Fish and Game Commission, State of California. Nongame Wildlife Program Report 2010–4

Bonnet X, Naulleau G, Shine R (1999) The dangers of leaving home: dispersal and mortality in snakes. Biol Conserv 89(1):39–50

Borda-de-Água L, Grilo C, Pereira HM (2014) Modeling the impact of road mortality on barn owl (Tyto alba) populations using age-structured models. Ecol Model 276:29–37

Bourque R (2008) [North Coast] spatial ecology of an inland population of the foothill yellow-legged frog (Rana boylii) in Tehama County, California. Masters Thesis, California State University, Humboldt, pp 107

Brehme CS, Tracey JA, McClenaghan LR, Fisher RN (2013) Permeability of roads to movement of scrubland lizards and small mammals. Conserv Biol 27(4):710–720

Bulger JB, Scott NJ, Seymour RB (2003) Terrestrial activity and conservation of adult California red-legged frogs Rana aurora draytonii in coastal forests and grasslands. Biol Conserv 110(1):85–95

California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) (2016a) Threatened and endangered species. http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/t_e_spp/ (accessed August 2016)

California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) (2016b) A status review of the flat-tailed horned lizard (Phrynosoma mcallii) in California. Report to the Fish and Game Commission

Carr LW, Fahrig L (2001) Effect of road traffic on two amphibian species of differing vagility. Conserv Biol 15(4):1071–1078

Case TJ, Fisher RN (2001) Measuring and predicting species presence: coastal sage scrub case study. In: Hunsaker CT, Goodchild MF, Friedl MA, Case TJ (eds) Spatial uncertainty in ecology. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 47–71

Clark RW, Brown WS, Stechert R, Zamudio KR (2010) Roads, interrupted dispersal, and genetic diversity in timber rattlesnakes. Conserv Biol 24(4):1059–1069

Clarkin K, Conner A, Furniss MJ, Gibernick B, Love M, Moynan K, Wilson S (2005) National inventory and assessment procedure for identifying barriers to aquatic organism passage at road-stream crossings. US Dep Agric for Serv. http://www.stream.fs.fed.us/publications/PDFs/NIAP.pdf

Colino-Rabanal VJ, Lizana M (2012) Herpetofauna and roads: a review. Basic Appl Herpetol 26:5–31

Colley M, Lougheed SC, Otterbein K, Litzgus JD (2017) Mitigation reduces road mortality of a threatened rattlesnake. Wildlife Res. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR16130

Congress US (1973) Endangered species act. US Code 16:1534–1544

COSEWIC (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada) (2012) COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Western Toad Anaxyrus boreas in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiv + 71 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm)

COSEWIC (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada) (2015) COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Northern Red-legged Frog Rana aurora in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xii + 69 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm)

Crawford BA (2015) Lessons from terrapin mortality and management on the Jekyll Island Causeway, Georgia, USA. In: Andrews KM, Nanjappa P, Riley SPD (eds) Roads and ecological infrastructure. Concepts and applications for small animals. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp 21–41

D’Amico M, Román J, De los Reyes L, Revilla E (2015) Vertebrate road-kill patterns in Mediterranean habitats: who, when and where. Biol Conserv 191:234–242

D’Amico M, Périquet S, Román J, Revilla E (2016) Road avoidance responses determine the impact of heterogeneous road networks at a regional scale. J Appl Ecol 53(1):181–190

Dodd CK, Barichivich WJ, Smith LL (2004) Effectiveness of a barrier wall and culverts in reducing wildlife mortality on a heavily traveled highway in Florida. Biol Conserv 118(5):619–631

Eigenbrod F, Hecnar SJ, Fahrig L (2008) The relative effects of road traffic and forest cover on anuran populations. Biol Conserv 141(1):35–46

Evelyn CJ, Sweet SS (2012) Conservation status of amphibians and reptiles on USDA National Forests, Pacific Southwest Region, 2012. Prepared for: USDA National Forest Service, Region 5, Pacific Southwest Region

Fahrig L, Rytwinski T (2009) Effects of roads on animal abundance: an empirical review and synthesis. Ecol Soc 14. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss11/art21

Fahrig L, Pedlar JH, Pope SE, Taylor PD, Wegner JF (1995) Effect of road traffic on amphibian density. Biol Conserv 73(3):177–182

Fellers GM, Kleeman PM (2007) California red-legged frog (Rana draytonii) movement and habitat use: implications for conservation. J Herpetol 41(2):276–286

Forman RT, Sperling D, Bissonette JA, Clevenger AP, Cutshall CD, Dale VH, Fahrig L, France R, Goldman CR, Heanue K, Jones JA (2003) Road ecology. Science and Solutions. Island Press, Washington

Furniss MJ, Roelofs TD, Yee CS (1991) Road construction and maintenance. Am Fish Soc Special Publ 19:297–323

Gibbs JP (1998) Amphibian movements in response to forest edges, roads, and streambeds in southern New England. J Wildl Manage 62:584–589

Gibbs JP, Shriver WG (2002) Estimating the effects of road mortality on turtle populations. Conserv Biol 16(6):1647–1652

Gibbs JP, Shriver WG (2005) Can road mortality limit populations of pool-breeding amphibians? Wetl Ecol Manag 13:281–289

Glista DJ, DeVault TL, DeWoody JA (2008) Vertebrate road mortality predominantly impacts amphibians. Herpetol Conserv Biol 3(1):77–87

Goodman RH, Stewart GR (2000) Aquatic home ranges of female Western Pond Turtles, Clemmys marmorata, at two sites in Southern California. Chelonian Conserv Biol 3(4):743–744

Gregory PT (1984) Communal denning in snakes. In: Seigel RA, Hunt LE, Knight JL, Maralet LA, Zuschlag NL (eds) Contributions to vertebrate ecology and systematics: a tribute to Henry S. Fitch. University of Kansas Museum of Natural History Special Publication 10:57–75

Halstead BJ, Skalos SM, Wylie GD, Casazza ML (2015) Terrestrial ecology of semi-aquatic giant gartersnakes (Thamnophis gigas). Herpetol Conserv Bio 10(2):633–644

Hayes MP, Rombough CJ, Hayes CB (2007) Natural History: Rana aurora (Northern red-legged frog) movement. Herpetol Rev 38:192–193

Hensley FR, Jones TR, Maxwell MS, Adams LJ, Nedella NS (2010) Demography, terrestrial behavior, and growth of Sonora mud turtles (Kinosternon sonoriense) in an extreme habitat. Herpetol Monogr 24:174–193

Hermann HW, Pozarowski KM, Ochoa A, Schuett GW (2017) An interstate highway affects gene flow in a top reptilian predator (Crotalus atrox) of the Sonoran Desert. Conserv Genet 18:911–924

Hickman JC (ed) (1993) The Jepson manual of higher plants of California. University of California Press, Berkeley

Hobday AJ, Smith ADM, Stobutzki IC, Bulman C, Daley R, Dambacher JM, Deng RA, Dowdney J, Fuller M, Furlani D, Griffiths SP (2011) Ecological risk assessment for the effects of fishing. Fish Res 108(2):372–384

Houlahan JE, Findlay CS (2003) The effects of adjacent land use on wetland amphibian species richness and community composition. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 60:1078–1094

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I (2005) Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 5(1):1

IUCN (2017) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017-1. http://www.iucnredlist.org

Jackson ND, Fahrig L (2011) Relative effects of road mortality and decreased connectivity on population genetic diversity. Biol Conserv 144(12):3143–3148

Jackson SD, Langen TA, Marsh DM, Andrews KM (2015) Natural history and physiological characteristics of small animals in relation to roads. In: Andrews KM, Nanjappa P, Riley SPD (eds) Roads and ecological infrastructure. Concepts and applications for small animals. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp 21–41

Jacobson SL, Bliss-Ketchum LL, Rivera CE, Smith WP (2016) A behavior-based framework for assessing barrier effects to wildlife from vehicle traffic volume. Ecosphere 7(4):e01345

Jaeger JA (2000) Landscape division, splitting index, and effective mesh size: new measures of landscape fragmentation. Land Ecol 15(2):115–130

Jaeger JA, Bowman J, Brennan J, Fahrig L, Bert D, Bouchard J, Charbonneau N, Frank K, Gruber B, von Toschanowitz KT (2005) Predicting when animal populations are at risk from roads: an interactive model of road avoidance behavior. Ecol Model 185(2):329–348

Januchowski-Hartley SR, McIntyre PB, Diebel M, Doran PJ, Infante DM, Joseph C, Allan JD (2013) Restoring aquatic ecosystem connectivity requires expanding inventories of both dams and road crossings. Front Ecol Environ 11(4):211–217

Jochimsen DM, Peterson CR, Andrews KM, Gibbons JW, Drawer E (2004) A literature review of the effects of roads on amphibians and reptiles and the measures used to minimize those effects. USDA Forest Service, Idaho Fish and Game Department, Washington, DC

Jochimsen DM, Peterson CR, Harmon LJ (2014) Influence of ecology and landscape on snake road mortality in a sagebrush-steppe ecosystem. Anim Conserv 17(6):583–592

Jones TR, Babb RD, Hensley FR, LiWanPo C, Sullivan BK (2011) Sonoran Desert snake communities at two sites: concordance and effects of increased road traffic. Herpetol Conserv Biol 6(1):61–71

Kemp PS, O’hanley JR (2010) Procedures for evaluating and prioritising the removal of fish passage barriers: a synthesis. Fish Manag Ecol 17(4):297–322

Klauber LM (1931) A statistical survey of the snakes of the southern border of California. Bull Zool Soc San Diego 8:1–93

Kwiatkowski MA, Schuett GW, Repp RA, Nowak EM, Sullivan BK (2008) Does urbanization influence the spatial ecology of Gila monsters in the Sonoran Desert? J Zool 276(4):350–357

Langen TA, Ogden KM, Schwarting LL (2009) Predicting hot spots of herpetofauna road mortality along highway networks. J Wildl Manag 73(1):104–114

Langen TA, Andrews KM, Brady SP, Karraker NE, Smith DJ (2015a) Road effects on habitat quality for small animals. In: Andrews KM, Nanjappa P, Riley SPD (eds) Roads and ecological infrastructure. Concepts and applications for small animals. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp 21–41

Langen TA, Gunson KE, Jackson SD, Smith DJ, Ruediger W (2015b) Planning and designing mitigation of road effects on small animals. In: Andrews KM, Nanjappa P, Riley SPD (eds) Roads and ecological infrastructure. Concepts and applications for small animals. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp 146–177

Langton TES (2015) A history of small animal road ecology. Roads and ecological infrastructure. Concepts and applications for small animals. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp 21–41

Lannoo MJ (2005) Amphibian declines: the conservation status of United States species. University of California Press, Berkeley

Levine KK (2013) California amphibian and reptile crossing preliminary investigation. Report to Caltrans Division of Environmental Planning

Linkov I, Satterstrom FK, Kiker G, Batchelor C, Bridges T, Ferguson E (2006) From comparative risk assessment to multi-criteria decision analysis and adaptive management: recent developments and applications. Environ Int 32(8):1072–1093

Litvaitis JA, Tash JP (2008) An approach toward understanding wildlife-vehicle collisions. Environ Manag 42(4):688–697

Loraamm RW, Downs JA (2016) A wildlife movement approach to optimally locate wildlife crossing structures. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 30(1):74–88

Mace GM, Collar NJ, Gaston KJ, Hilton-Taylor C, Akçakaya HR, Leader-Williams N, Milner-Gulland EJ, Stuart SN (2008) Quantification of extinction risk: IUCN’s system for classifying threatened species. Conserv Biol 22(6):1424–1442

Marsh DM, Jaeger JAG (2015) Direct effects of roads on small animal populations. Roads and ecological infrastructure. Concepts and applications for small animals. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp 21–41

Martinez-Solano I, Jockusch EL, Wake DB (2007) Extreme population subdivision throughout a continuous range: phylogeography of Batrachoseps attenuatus (Caudata: Plethodontidae) in western North America. Mol Ecol 16(20):4335–4355

Mazerolle MJ, Huot M, Gravel M (2005) Behavior of amphibians on the road in response to car traffic. Herpetologica 61(4):380–388

Mccardle LD, Fontenot CL (2016) The influence of thermal biology on road mortality risk in snakes. J Thermal Biol 56:39–49

Mitrovich MJ (2006) A case study in conservation science: The spatial ecology and evolutionary history of the coachwhip snake (Masticophis flagellum) and striped racer (M. lateralis). Ph.D. dissertation. University of California, Davis, and San Diego State University. San Diego

Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, Da Fonseca GA, Kent J (2000) Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403(6772):853–858

NatureServe (2017) NatureServe explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. http://explorer.natureserve.org. (Accessed: May 25, 2017)

Orłowski G (2007) Spatial distribution and seasonal pattern in road mortality of the common toad Bufo bufo in an agricultural landscape of south-western Poland. Amphibia-Reptilia 28(1):25–31

Peaden JM, Tuberville TD, Buhlmann KA, Nafus MG, Todd BD (2016) Delimiting road-effect zones for threatened species: implications for mitigation fencing. Wildl Res 42(8):650–659

Peaden JM, Nowakowski AJ, Tuberville TD, Buhlmann KA, Todd BD (2017) Effects of roads and roadside fencing on movements, space use, and carapace temperatures of a threatened tortoise. Biol Conserv 214:13–22

Pianka ER (1966) Convexity, desert lizards, and spatial heterogeneity. Ecology 47(6):1055–1059

Pilliod DS, Welty JL, Stafford R (2013) Terrestrial movement patterns of western pond turtles (Actinemys marmorata) in central California. Herpetol Conserv Bio 8(1):207–221

Polak T, Rhodes JR, Jones D, Possingham HP (2014) Optimal planning for mitigating the impacts of roads on wildlife. J Appl Ecol 51(3):726–734

Rathbun GB, Scott NJ Jr, Murphey TG (2002) Terrestrial habitat use by Pacific pond turtles in a Mediterranean climate. Southwest Nat 47(2):225–235

Reese DA, Welsh HH (1997) Use of terrestrial habitat by western pond turtles, Clemmys marmorata: implications for management. In Proceedings: Conservation, restoration, and management of tortoises and turtles–an international conference. State University of New York, Purchase, New York, pp 352–357)

Reid BN, Peery MZ (2014) Land use patterns skew sex ratios, decrease genetic diversity and trump the effects of recent climate change in an endangered turtle. Divers Distrib 20(12):1425–1437

Roe JH, Gibson J, Kingsbury BA (2006) Beyond the wetland border: estimating the impact of roads for two species of water snakes. Biol Conserv 130(2):161–168

Rosen PC, Lowe CH (1994) Highway mortality of snakes in the Sonoran Desert of southern Arizona. Biol Conserv 68(2):143–148

Rosenberg D, Gervais J, Vesely D, Barnes S, Holts L, Horn R, Swift R, Todd L, Yee C (2009) Conservation assessment of the Western pond turtle in Oregon (Actinemys marmorata). USDI Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service, USDA Forest Service Region 6, Oregon

Rouse JD, Willson RJ, Black R, Brooks RJ (2011) Movement and spatial dispersion of Sistrurus catenatus and Heterodon platirhinos: implications for interactions with roads. Copeia 3:443–456

Row JR, Blouin-Demers G, Weatherhead PJ (2007) Demographic effects of road mortality in black ratsnakes (Elaphe obsoleta). Biol Conserv 137(1):117–124

Rudolph DC, Burgdorf SJ, Conner RN, Schaefer RR (1999) Preliminary evaluation of the impact of roads and associated vehicular traffic on snake populations in eastern Texas. In: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Wildlife Ecology and Transportation. FL-ER-73-99. Evink GL, Garrett P, Zeigler D (eds) Florida Department of Transportation, Tallahassee, Florida, pp 129–136

Rytwinski T, Fahrig L (2012) Do species life history traits explain population responses to roads? A meta-analysis. Biol Conserv 147(1):87–98

Rytwinski T, Fahrig L (2013) Why are some animal populations unaffected or positively affected by roads? Oecologia 173(3):1143–1156

Rytwinski T, Fahrig L (2015) The impacts of roads and traffic on terrestrial animal populations. Handbook of Road Ecology. Wiley, New York, pp 237–246

Semlitsch RD (1998) Biological delineation of terrestrial buffer zones for pond-breeding salamanders. Conserv Biol 12(5):1113–1119

Semlitsch RD (2008) Differentiating migration and dispersal processes for pond-breeding amphibians. J Wildl Manag 72(1):260–267

Semlitsch RD, Bodie JR (2003) Biological criteria for buffer zones around wetlands and riparian habitats for amphibians and reptiles. Conserv Biol 17(5):1219–1228

Shilling F, Waetjen D (2017) California Roadkill Observation System. UC Davis Road Ecology Center. http://wildlifecrossing.net/california(accessed April 2017)

Siers SR, Reed RN, Savidge JA (2016) To cross or not to cross: modeling wildlife road crossings as a binary response variable with contextual predictors. Ecosphere 7(5):19

Stebbins RC, McGinnis SM (2012) Field guide to amphibians and reptiles of California, vol 103. University of California Press, Berkeley

Steen DA, Aresco MJ, Beilke SG, Compton BW, Condon EP, Dodd KC, Forrester H, Gibbons JW, Greene JL, Johnson G, Langen TA (2006) Relative vulnerability of female turtles to road mortality. Anim Conserv 9(3):269–273

Sullivan BK (2012) Road riding. In: McDiarmid RW (ed) Reptile biodiversity: standard methods for inventory and monitoring. University of California Press, Oakland, CA, pp 215–218

Suter GW II (2016) Ecological risk assessment. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL

Thomson RC, Wright AN, Shaffer HB (2016) California amphibian and reptile species of special concern. University of California Press, Oakland, CA

Trenham PC (1998) Demography, migration, and metapopulation structure of pond-breeding salamanders. Ph.D. dissertation. University of California, Davis

Trenham PC, Koenig WD, Shaffer HB (2001) Spatially autocorrelated demography and interpond dispersal in the salamander Ambystoma californiense. Ecology 82(12):3519–3530

Trenham PC, Koenig WD, Mossman MJ, Stark SL, Jagger LA (2003) Regional dynamics of wetland-breeding frogs and toads: turnover and synchrony. Ecol Appl 13(6):1522–1532

US Fish and Wildlife (USFWS) (2016) United States species: Endangered and threatened wildlife (50 CFR 17.11). https://www.fws.gov/endangered/species/us-species.html (accessed August 2016)

US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (2002) Recovery plan for the California red-legged frog (Rana aurora draytonii). US Fish and Wildlife Service, Portland, Oregon, viii + 173 pp

US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (2009) Rana pretiosa. Species assessment and listing priority assignment form. USFWS Region 1, Portland

US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (2011) Alameda whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus) 5-year review summary and evaluation. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Sacramento, CA

van der Ree R, Smith DJ, Grilo C (2015) Handbook of road ecology. Wiley, New York

Vangel MG (2015) Tolerance interval. Statistics Reference Online. Wiley StatsRef, New York, pp 1–7

Vences M, Wake DB (2007) Speciation, species boundaries and phylogeography of amphibians. Amphib Biol 7:2613–2671

Watson JW, McAllister KR, Pierce DJ (2003) Home ranges, movements, and habitat selection of Oregon Spotted Frogs (Rana pretiosa). J Herp 37(2):292–300

Young KV, Young AT (2000) Final report: scientific study of the flat-tailed horned lizard, Phrynosoma mcallii. US Dept. of Navy Contracts N68711-95-LT-C0032, N68711-95-LT-C0035. 72 pp

Zimmermann Teixeira F, Kindel A, Hartz S, Mitchell S, Fahrig L (2017) When road-kill hotspots do not indicate the best sites for road-kill mitigation. J Appl Ecol 54(5):1544–1551

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the support and feedback from Harold Hunt, Amy Golden, and James Henke from the California Department of Transportation. Tony Clevenger, Tom Langton, Jeff Tracey, Amber Wright, Laura Patterson, Brian Halstead, Kari Gunson, Jon Richmond, and two anonymous reviewers gave thoughtful feedback that improved this manuscript. We thank Tristan Edgarian for reviewing and cross-checking our life history data and movement data and references. Finally, we appreciate all of the scientists that contributed life history information for California reptile and amphibian species (Appendices). Funding came from Caltrans Department of Transportation Contract #65A0553 and the Ecosystems Mission Area in USGS. This is contribution number 615 of the U.S. Geological Survey Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative (ARMI). The use of trade, product or firm names in this publication does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Brehme, C.S., Hathaway, S.A. & Fisher, R.N. An objective road risk assessment method for multiple species: ranking 166 reptiles and amphibians in California. Landscape Ecol 33, 911–935 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-018-0640-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-018-0640-1