Abstract

This paper offers a dialectical analysis of the law relating to the Greek crisis. The form and content of the measures introduced in the Greek legal system to deal with the debt crisis is examined under the concept of ‘necessity’. It is argued that this concept, used by the Greek Council of State to justify the constitutionality of these measures, opens a path for a more comprehensive analysis of the measures implemented through the mechanism of the Greek Memoranda of Understanding. The measures are seen as ‘necessary’: on the one hand in their accordance and basis on principles of the European Union; on the other hand in their class orientation and reflecting of specific social (class) interests. But despite their necessity, neither their content, nor the form of implementation of these measures is fixed; it is rather contingent, i.e. dependent on the level of intensification of social (class and intra-class) and economic antagonisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Is a Damoclean sword hung over Greece and other EU countries? This metaphorical question could be answered in the affirmative, on the assumption that this sword takes the form of Memoranda of Understanding. Perhaps more accurately, one could argue that this sword takes the form of an EU-wide supervisory mechanism, the framework for which has been set by the Fiscal CompactFootnote 1 of 2012. Karl Marx uses the same metaphor to describe the change in the form of exercise of bourgeois political power during Louis Napoleon’s reign (Marx 2009). This change involved the prioritisation of executive procedures at the expense of parliamentary discussions. The bourgeoisie that had previously extolled the liberal freedoms of parliamentarism now promoted the strengthening of executive powers and the removal of decision-making from popular strata; a tactic that was enabled by the fundamental aspect of the modern political and legal apparatus, described as raison d’état, and has to do with the vital need of the state to perpetuate itself as an entity.

In analysing this fundamental element of modern constitutional and political structures, Marx discerned the social content behind the political form. He identified the intensification of social and economic contradictions as the motor behind this change in the form of exercise of public power. The point of departure in this paper is that the form of the Greek crisis legislation can only be explained if it is assessed in its unity with the socio-economic content. Legislative form and content are to be seen in their dynamic unity, reflecting the level of intensification of social antagonisms. In the context of the Greek crisis legislation, the exceptional form is presented in the form of the Memoranda of Understanding. This exceptional form is certainly not an EU phenomenon but originated in the transformation of South-American economies on the basis of aggressive capitalist policies imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The ‘Greek crisis legislation’ includes the three Memoranda of Understanding, the corresponding primary (i.e. four implementing Acts, N.3845/2010, N.4046/2012, N.4093/2012, and N.4336/2015) and secondary legislation implementing them within the Greek legal order, and their basis on EU law. All three Memoranda of Understanding (‘Memoranda’) were agreed upon by the Greek government and the Troika—the IMF, European Central Bank (‘ECB’), and European Union Commission (‘Commission’)—and accompanied the Greek bail-out. In fact the bail-out is conditional upon the implementation of these measures, according to the principle of conditionality, which accompany all similar programmes drafted by the IMF.

In this paper, the Greek crisis legislation will be submitted to a dialectical analysis, in the sense that the measures included therein will be examined as a unity of form and content. The term dialectics is used in full awareness of the bibliographyFootnote 2—to which we concur—that the dialectics cannot be characterised as merely a method; it is rather a mode of conceiving reality in its many-sided and contradictory movement. Dialectics is identified with many-sided analysis of processes in their interconnection. It, therefore, helps us grasp the totality of changes in a social formation; the changes in the legal and political forms are assessed in their mutual unity with social and economic change.

The dialectical pair of form and content is a crucial analytical tool for this endeavour. Marx’s theory of labour uses this conceptual pair in the process of moving from the relation between ‘free and equal’ legal subjects in the sphere of exchange (abstract legal form) to the relation between exploiters and exploited in the depths of the production process (concrete socio-economic content). But it is even more important to grasp that the economic content and the legal form are abstract constitutive elements—i.e. two sides—of one and the same actual relation. These abstract economic and legal relations do not exist in their ‘pure form’ in empirical reality; only in the field of theoretical abstraction can the legal form be separated from its content (Lapayeva 1982, p. 55).

Consequently, submitting the Greek crisis legislation to a dialectical analysis essentially means that the form of the Memorandum will be examined together with the set of class-oriented measures it introduces. The Memoranda, as form of implementation of these measures, invoke the ‘exceptional circumstance’ of the ‘unprecedented’ Greek crisis in order to ‘exceptionally’ justify the implementation of these measures. However, the simple condemnation of the exceptional form in favour of a normal procedure, or in favour of the ‘true essence’ of the Constitution, is not enough. The Greek Council of State (CoS) has accepted the constitutionality of these measures based on the justification that they are ‘necessary’.

On the basis of this ‘necessity’, the Memoranda are analysed as the form of implementation of measures that were seen as necessary even before the crisis. The fact that they were ‘necessary’ does not mean, of course, that the content of these measures was ‘fixed’. It is important then to ask ourselves why these specific measures were introduced and look for the answer in the dynamic concept of class struggle, in the sense of the intensification of social and economic antagonisms. If there has been a change in form (the proliferation of the form of the Memoranda in Europe as well as a more general tendency of ‘necessary’ legislation passed in the ‘general interest’) we need to ask ourselves what is the content of this form. What is ‘necessary’ about these measures? Why and for whom are they ‘necessary’?

On the basis of the above, the paper is structured as follows: the first section begins with an analysis of the form of the Memorandum. This form was introduced in order to cope with the effects of the Greek sovereign debt crisis in an efficient manner, through the introduction of measures which are necessary in order for the Greek economy not to default. It is argued that the efficiency of the Memorandum is strongly connected with the language of necessity and the phenomenon of judicial deference. This leads to a critical analysis of the concept of necessity and general interest, with reference to Hegel’s dialectical analysis. This analysis of necessity points towards the socio-economic content of the measures, which are class-oriented and contingent upon the intensification of socio-economic contradictions.

To understand the necessity of the form of the Memorandum one has to understand the content of the measures introduced with the form of the Memorandum. This endeavour includes two parts. In the second section, the content of ‘necessity’ is sought in EU legislation. EU law is analysed as an integral whole and a principled system, i.e. a totality of rules and principles which relate to each other and are informed by a particular political conception of how social and economic relations should develop and be regulated. The Memorandum is seen as a form of implementation of policies and principles found in EU legal and political documents.

The third section of the paper looks at the socio-economic contradictions and their intensification due to the uneven development in capitalism, which necessitates the measures implemented through the form of the Memorandum. The third Greek Memorandum ensures the implementation of measures which are introduced across the EU according to ‘best practice’. The concept of ‘best practice’ stands for a practice which is ‘necessary’ and which is followed with or without the Memorandum form. This section involves a comparative analysis of labour law reforms implemented in countries without memoranda, such as France and Italy, in order to identify what is considered ‘necessary’ in these ‘best practices’. It is argued that these measures, which are ‘necessary’ to restore the competitiveness of each Member State and the EU as a whole, are due to the intensification of intra-class antagonisms which leads to intensification of class struggle. On the basis of capitalist uneven development, capitalist countries need to lower wages and increase exploitation in order to compete amongst themselves and with other antagonists.

Therefore, the concept of class struggle—in the sense of a dynamic process of intensification of social (class and intra-class) contradictions which necessitates changes in the form of exercise of public power whenever there is a ‘need’—is crucial for the analysis. The last section examines the class-orientation of the Greek crisis legislation. It is argued that both form and content are contingent upon the intensification of class and intra-class antagonisms. In this way, the Greek crisis legislation is assessed in the context of the capitalist crisis, necessitated by the contradictions (overproduction, over-accumulation and uneven development) of capitalism; a global crisis affecting all monopoly groups and transnational companies (magnifying the interdependency of globalised capitalism) but, more importantly, affecting the workers and popular strata throughout the world, whose exploitation must be intensified so that capital might hope for a way out of the crisis.

The Necessary Form of the Memorandum

Let us begin the examination of the Greek crisis legislation as a unity of form and content with the first of the constituent parts of this relation, i.e. the form and, more specifically, the form of the Memorandum. Why the Memorandum and why in Greece? The goal is to see why the Memorandum was considered the appropriate form of the Greek crisis legislation, as well as to identify the relation between the form of the Memorandum and the language of necessity used by the Greek courts to justify its implementation in the Greek legal order. As mentioned above, Memoranda of Understanding were an integral part of the IMF’s structural adjustment programmes which introduced aggressive capitalist policies in South American economies. In the last decade Memoranda have been essential parts of the agreements between several EU Member States (Greece, Ireland, and Portugal) and the IMF and EU institutions for the bail-out of these Member States’ economies.

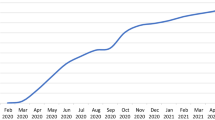

Crucial for the development of these policies and the adoption of this form of implementation has been the construction of the capitalist crisis as a ‘sovereign debt crisis’. The dominant interpretation of the economic crisis, as it developed in the Eurozone countries, attributed the crisis to weaknesses of governance of these specific countries, as well as the ‘euro area’ in general.Footnote 3 In this context the focus was on reasons endogenous to these specific Member States: administrative reasons (systems which foster political clientelism, and weak control of public expenditure); and economic reasons (low competitiveness, trade and investment imbalances, and fiscal mismanagement). According to this narrative, Member States which had failed to implement measures to enhance their competitiveness could not keep up with strong and growing economies and resorted to heavy borrowing, therefore increasing their sovereign debt.

Consequently, the Memorandum of Understanding aims to serve a double purpose of dealing with the sovereign debt through the provision of bilateral loans, while introducing into the legal systems of these Member States the necessary remedies for their respective economies. The Memorandum as form of implementation achieves the following: on the one hand, it is considered necessary in order to meet the exigencies of the crisis; on the other hand, it is considered binding because it is part of an international agreement and failure to meet the objectives set therein will automatically result in the default of the Greek economy, which, according to the narrative which has shaped Greek politics for the last years, will bring economic disaster, chaos, and poverty.

The Memoranda comprise documents of at least 600 pages each, containing a detailed list of measures aimed at the radical reorientation of the Greek economy and encompassing the whole spectrum of public policy-making—fiscal policy; fiscal institutional reforms; financial sector regulation and supervision; privatisations, and ‘growth-enhancing structural reforms’, i.e. labour market reforms; enhancement of competition in open markets; and reformation of the educational and judicial systems. Crucially, the ratification of all three Memoranda by the Hellenic Parliament took place with the use of the emergency parliamentary procedure.Footnote 4 As a result of the use of this exceptional procedure, there was no substantive public consultation over the reforms. This was justified on the basis that ‘it was not possible to accommodate participatory methods when Greece was about to default on its loans’ (Koukiadaki and Kretsos 2012).

The form of the Memorandum can, thus, be explained by reference to its efficiency. However, this efficiency could be undermined. For a dualist legal system, like Greece, implementation of the Memorandum can only be incorporated into the Greek legal order through an Act of Parliament. Furthermore, in Greece judicial review involves the courts checking the constitutionality of statutes. In addition to this, the legislation included in Memoranda arguably contradicts certain rights safeguarded in the Greek Constitution (such as Articles 22 and 23, i.e. the right to work and the freedom to unionise respectively).Footnote 5 So, the form of the Memorandum could be rendered ineffective if Acts of Parliament were found unconstitutional by the Greek Council of State.

We come to the conclusion that the form of the Memorandum would not be so efficient had it not been accompanied by another closely associated form of exercise of public power, i.e. the phenomenon of judicial deference, which involves the alignment of the will of the judiciary to the will of the executive. In the UK context, this doctrine has been applied by UK courtsFootnote 6 to justify the reluctance of judges to deal with ‘political’ questions relating to public emergency, national security, national or general interest. As Lord Carswell put it, ‘a rule of abstinence should apply’ and the court should avoid interfering with what is essentially a political judgment.Footnote 7 This alignment is effectuated through the use of the interrelated concepts of necessity and general (or public) interest. The courts lack the democratic legitimacy and expertise to decide on what constitutes a national emergency and would abstain from reviewing measures considered necessary by the executive to deal with a crisis.

To return to our object of analysis, the form of the Memorandum itself facilitates this phenomenon since the very rationale for introducing the Memorandum is the crisis, as well as the urgent nature of the measures. The principle of conditionality, which accompanies the Memorandum, feeds to the above. Therefore, the form of the Memorandum itself necessitates the language of necessity and general interest which is vital to the phenomenon of judicial deference. In the context of the Greek crisis legislation, the question ‘Quis judicabit?’ re-emerges, as the judiciary recedes before the political judgment of the legislator and his technocratic adequacy, proclaiming him, thus, the original interpreter of the crisis. The aligning of the two distinct wills (that of the judge and that of the legislator) in this internal dialogue of the state is evidence of the unity of the state in reproducing the bourgeois rule.

Let us elaborate on this point. The unity of the two wills, i.e. the will of the legislator and the will of the judge, is certainly not constant in a liberal constitutional democracy. In fact it is a broken unity, not only in ‘normal’ times, but also in times of ‘emergency’ as dictated by the principle of the ‘rule of law’. Such was the case in Judgment 2307/2014 of the Greek Council of State, which found unconstitutional a limited aspect of the labour-law regulations of the Second Memorandum, i.e. the unilateral recourse to arbitration. This is also evidence of law’s ‘relative autonomy’.Footnote 8 Law cannot be reduced to a voluntaristic phenomenon; it is not identified with the arbitrary will of the ruling class, however influenced it may be by the latter.

Nevertheless, Panayiotis Pikrammenos, former President of the Greek Council of State, in an article explaining Judgment 668/2012 of the Court on the constitutionality of the first Memorandum, argues that the exceptional circumstances, which necessitate the judge’s decision on whether the divergence from legal normality is justified, do not put the judge himself in the position of the Sovereign, in the Schmittian sense of the term (Pikrammenos 2012). Therefore, it is under this prism that we should assess the Greek case-law on the constitutionality of the Memoranda. The aforementioned Judgment 668/2012 adopted, according to Pikrammenos, many elements of the theory of the exception and the language of necessity.

In both this judgment and Judgment 2307/2014 of the Greek Council of State, on the constitutionality of the second Memorandum, it was held that reasons of ‘overriding public interest’ necessitated the loan agreement, and that full compliance with the principles of proportionality and necessity was achieved. According to the Court ‘the measures were neither inappropriate, nor can it be proven that they were not necessary’. They are ‘part of a larger program of fiscal adjustment’, and ‘they serve the public interest and the immediate need to address the economic needs of the country’.Footnote 9 So, according to the Court’s jurisprudence there is in fact an emergency to be met. However, the measures introduced to deal with this emergency are not temporary, and certainly not exceptional. They are, rather, considered as necessary measures, which form part of a larger programme of fiscal adjustment, and they serve the public interest.

Consequently, in spite of arguments that the country is under a state of emergency imposed by the Troika, the legal facts, i.e. the valid ratification of the measures by the Parliament and the decisive judgment of the courts, prove the integration of the Memoranda regulations in a regime of constitutional legality (Karavokyris 2014, p. 31). In addition to this, it is argued that the limitations on fiscal sovereignty stem not only from the programme imposed upon the Greek government by the Troika, its institutional creditors, due to its oversize sovereign debt and extreme deficit, but ‘simultaneously from the obligation of compliance with the commitments undertaken by the Greek government becoming a Member of the Eurozone, and signing as a sovereign state the Maastricht Treaty, the Lisbon Treaty, and the Stability and Growth Pact’ (Manitakis 2011, my emphasis).

Necessity and General Interest

As Pikrammenos admits, many elements of the language of necessity were used by the Greek courts. What is more, on a jurisprudential basis one would be justified in arguing that the legal form—and content—of the Memorandum was necessitated by the ‘general interest’. Let us then look at this concept, through which the appropriate measures for the securing of the state’s life are dressed in the gown of legality and constitutionality (Karavokyris 2014, p. 200). The idea of the general interest can be traced back to the Roman maxim of salus populi suprema lex esto. This phrase appears in ‘The Laws’ of Cicero as part of an ideal constitution embodying the principles of the uncorrupted Republic. When faced with a violent threat to the security of the republic, the Senate was to designate the consuls as supreme military commanders and authorise them to take any measures they thought necessary to counter the threat (Poole 2015, p. 1). The state assumes an exceptional form to protect the ‘safety’ and the ‘welfare’ of the ‘people’.

In the Greek crisis legislation, the fiscal-economic content of ‘public interest’ is revealed, as ‘necessity’ consists in safeguarding fiscal balance and public wealth. The positivist approach to this notion holds that ‘public interest’ is expanded so as to include the fiscal balance and avoidance of economic disaster of the country (Karavokyris 2014, p. 93). While it is undoubtedly true that the abstract notion of ‘public interest’ has to acquire historically different meanings, since its elasticity allows it to develop and adapt to the concrete juridico-political conditions (Karavokyris 2014, p. 100), we wish to focus on the ideological function of this notion as a legitimating force, which seeks to obfuscate the class divisions and create and sustain a false, albeit necessary for the reproduction of the bourgeois state, idea of social cohesion. On this basis, a different understanding of necessity which contests the possibility of a general interest in a class-divided society is important for our analysis.

How can we speak of a ‘general interest’ and ‘welfare’ of the people as a whole in a class-divided society? To answer this question it is pertinent to critically discuss the concepts of ‘general interest’ and salus populi, with reference to G.W.F. Hegel’s analysis of the institution of Notrecht. This will lead to a dialectical understanding of necessity, unearthing the social contradiction that this notion serves to obfuscate.

One could argue that Hegel’s dialectical—i.e. many-sided—but idealist analysis is already ‘turned on its head’ at the point where he discusses the institution of the Notrecht (i.e. ‘right of need’). There, he reveals and places emphasis on the contradictions of property and propertylessness. For Hegel, an illegal action, such as theft, which infringes upon the right of property, may be justified on the basis of the institution of Notrecht. Notrecht is the right of extreme need, which can be invoked by a person who finds himself in a dire situation of propertylessness, such that his very existence is put in danger. Then, his right of need, his absolute right to his life, trumps the one-sided right of property.

Hegel sees the contradictions of modern civil society and its property regime as the social context which necessitates the appearance of such a legal institution. His analysis is juxtaposed to those of Kant and Fichte, for whom Notrecht is only related to exceptional situations; the Not stems from a natural catastrophe and from an accidental event and cannot question the existing legal system, let alone the social formation in its totality (Losurdo 2004, p. 157). On the contrary, Hegel argues that Notrecht is not to be confused with the jus necessitatis that refers to exceptional circumstances generally caused by natural disasters. The ‘Not’, i.e. the extreme need that causes Notrecht, is a social issue and refers to conflicts and concrete clashes brought on by the existing social relationships.

Additionally, Notrecht is not to be confused with the jus resistentiae which we find in Locke. Locke’s right to resistance is directly linked to the inviolability and fundamental role of property in civil society; an individual’s property is more inviolable than his own life. For Locke, tyranny is the violation of private property and it is lawful to resist that tyranny: this is the essence of Locke’s right to resistance. On the contrary, Hegel’s Notrecht is the ‘right of extreme need’ of those who risk starving to death; not only do they have the right to steal the bread that will keep them alive, but the ‘absolute right’ to transgress the right of property, that legal norm which condemns theft (Losurdo 2004, p. 87). Hegel prioritises the right to keep oneself alive, if found in a state of extreme poverty due to socio-economic contradictions over the abstract right to property.

Crucial points for the analysis of the form of exercise of public power can be derived from the above examination. So far, necessity has been identified with the fundamental need of the state to reproduce its rule and the objective need of reproducing a regime of power, property and productive relations. On the contrary, Hegel presents a different ‘necessity’: a Not (need) as the need of man to feed himself; a necessity, therefore, which threatens, contradicts and, in fact, violates the property regime that the necessity we encountered so far functions to reproduce. In fact, this concept of necessity could serve as a basis for the social rights of the exploited classes, which are under attack by crisis legislation.

Consequently, we arrive at two fundamentally different conceptions of ‘necessity’. To put it in different terms, Hegel reveals that in a class-divided society, which develops through contradictions, the salus populi can be as validly interpreted as necessitating the protection of private property, as much as necessitating the violation of private property. Furthermore, these two conflicting conceptions reflect the social contradictions which give rise to them and, consequently, the conflicting social interests between the propertied classes and the propertyless. The social-class contradictions between propertied and propertyless, exploiters and exploited, cancels out the generality of the concept of people and general interest.

The full implications of Hegel’s dialectical analysis fall outside the scope of this paper. However, a crucial insight into the relationship between form and content is offered. The dialectical understanding of necessity does not refer to general interest and public welfare but to what is necessary for the reproduction of capitalist relations. In that sense, necessity is on the one hand shown to be ‘relative’ to class position. For instance—and this is where Hegel’s Notrecht is important in this context—for the poor, necessity is subsistence and theft, whereas for the rich, necessity is property and its protection. In the same manner and in the context of the Greek crisis legislation, for capital, necessity is the legislation enabling conditions of intensified exploitation, whereas for the working class and popular strata, necessity is the contestation of these aggressive capitalist policies relations. Furthermore, and following from the above, the content of ‘necessary’ measures is contingent upon the intensification of contradictions—a point to which we shall return later, on the conflict between austerity and Keynesian approaches to the crisis. This dialectical understanding of necessity (as a legal term employed by the Greek Council of State, as well as a term which points towards social and economic needs and processes) opens the floor for an analysis of the socio-economic content of the Greek crisis legislation.

The Necessary Content of the Memorandum

What, then, is the content that needed implementation through the form of the Memorandum? To unearth the socio-economic content of the ‘necessary’ measures introduced through the form of the Memorandum one has to begin by looking at their basis in EU legislation. EU law is here analysed as an integral whole and a principled system, i.e. a totality of rules and principles which relate to each other and are informed by a particular political conception of how social and economic relations should develop and be regulated. In that way, the Memorandum is seen as a form of implementation of policies and principles found in EU legal and political documents.

It is here argued that European Union Law, the body of law which resulted from the limitation of competence or a transfer of powers from the States to the Community,Footnote 10 is a principled totality which consists of rules, principles and policies. It is also argued that some of these principles, which reflect a specific political conception of the way social and economic relations should develop, outweigh all others in a balancing process. To substantiate this claim, reference can be made to a number of ‘hard cases’, such as those of Laval (2007) and Viking (2007), where the relative strength of the principle of the freedom of establishment over other principles is mostly evident.

More specifically, in two of the most important Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) decisions on the relationship between national labour law provisions and fundamental EU principles, the place of labour law within the EU system of rules and principles was clarified. In Laval (2007) and Viking (2007) the CJEU held that the right to take industrial action is, on the one hand, a ‘fundamental right which forms an integral part of the general principles of community law’. On the other hand, the Court held that the consequence of recognising that the right to take industrial action has its origins in community law is that the right can only be exercised in a manner that is compatible with that law. The important consequence of this is that ‘the right is fettered in so far as it restricts freedom of movement and freedom of establishment such that where industrial action restricts freedom of movement or establishment, it will only be lawful if it is both justified and proportionate’ (Ornstein and Smith 2008).

It is evident from the above that the freedom of establishment outweighs any other conflicting principle of the EU legal system. As a result, the economic content of EU principles conditions and qualifies the exercise of fundamental social rights, such as the right to strike. Let us further develop this argument and provide a link to the Greek context, by looking at the recent opinion of Advocate General Wahl on a request for a preliminary ruling from the Greek Council of State. The legal issue arose on the occasion of a dispute between the Greek government and a cement company (AGET Iraklis 2016) after a decision of the latter to proceed to collective dismissals of its labour-force. The question referred to the CJEU (Case C-201/15) concerned the compatibility of Article 5(3) of Act 1387/1983 of the Hellenic Parliament with Articles 49 TFEU (freedom of establishment) and 63 TFEU (free movement of capital). In particular, Article 5(3) of the above provision lays down as a condition for collective redundancies to be effected in a specific undertaking that the administrative authorities must authorise the redundancies in question on the basis of criteria as to (a) the conditions in the labour market; (b) the situation of the undertaking; and (c) the interests of the national economy.

The Advocate General advanced the opinion that the Greek legislation regulating collective redundancies is incompatible with Article 49 TFEU because ‘the rule at issue is not appropriate for the purpose of protecting workers and, in any event, it goes beyond what is necessary to achieve that purpose’ (para. 76). The reason he gives for his opinion is based on a value judgment of the relation between labour legislation and the protection of workers. The Advocate General opines that the rule at issue merely gives the impression of being protective of workers. In reality, according to the Advocate, this protection is only temporary until the employer becomes insolvent (para. 73). Therefore, the presence of an acute economic crisis accompanied by unusual and extremely high unemployment rates cannot justify restricting the freedom of establishment and the freedom to conduct a business, by restricting the rights of employers to enact collective dismissals (para. 78).

The Advocate General’s opinion is an example of how essentially political ideas about how economy should be managed inform the content of a judicial opinion. In fact, according to the Advocate, the idea of a balancing exercise in this case is without an object: protecting the workers concerned is not at odds with either the freedom of establishment or the freedom to conduct a business (para. 74). The reason for this is that workers are best protected by an economic environment which fosters stable employment (para. 73). The Advocate’s opinion concludes with reference to the Third Memorandum introduced in the Greek legal order with Law No 4336/2015 and the political reasoning behind it: ‘in times of crisis, it is important to reduce all the factors which deter new undertakings from investing, as economic efficiency may help stimulate job creation and economic growth’ (para. 80, my emphasis). The way to achieve these—and subsequently to protect workers from unemployment—is for Greece to ‘undertake rigorous reviews and modernisation of collective bargaining, industrial action and, in line with the relevant EU directive and best practice, collective dismissals’.

As a result, in order for the workers to be protected against unemployment, any protection against collective dismissals has to be forfeited. It is argued that the essence of EU law is presumed in the Advocate’s opinion as coinciding with a specific purpose: competitiveness, growth, and job creation as a result of the free enterprise of companies and the reduction of all factors which deter new undertakings from investing. The Advocate General is advancing a teleological interpretation based on the principles and policies of EU law. He arrives at the conclusion that Greek law fails to protect from unemployment despite its declared intentions, because it is the opposite law that would protect from unemployment: a law that protects not the employee but the employer.

This opinion, informed by a particular political conception, reveals the EU legal system as a principled totality whose telos is found in the principles of growth and competitiveness and the accommodating principles of budgetary efficiency and flexibility. In fact, it manifests that fiscal principles go hand in hand with labour law reforms. The principle of growth translates into investment. And as we saw above, no enterprise will invest unless it is reassured that the production costs are reduced. Central among these costs that need to be reduced ‘for an agreeable investing environment’ is the cost of labour. The way to reduce the cost of labour is by reducing the protection of workers, either through amending the legislation which regulates collective dismissals, or by changing the level at which collective bargaining takes place and moving it closer to the enterprise level, or through other means (such as reducing the possibility of industrial action). The same policies that would lead to growth are the ones providing a particular economic environment with a competitive advantage, according to the same politico-economic conception.

The fundamental EU monetary principle of budgetary efficiency, proclaimed in the Fiscal CompactFootnote 11 and confirmed by the Pringle decision,Footnote 12 is supplemented with the economic principles of growth and competitiveness. These necessary principles are promoted by the Memorandum due to the exacerbation of the socio-economic contradictions following the 2008 global financial crisis. We saw previously that the Greek CoS accepts the constitutionality of the measures introduced with the Memoranda and their basis on EU legislation. The Court invokes the notion of ‘supreme social interest’ in order to justify the constitutional compliance of the measures which contribute ‘to the reduction of unemployment and the enhancement of competitiveness of the national economy’.Footnote 13 The main EU economic principles of competitiveness and growth are presented, in their acceptance by the Court, as of ‘supreme social interest’.

Therefore, ‘necessity’ is concretised in the form of the Memorandum and the content of the labour law reforms as part of a programme of internal devaluation, which is supposed to lead to growth and competitiveness (Lapavitsas et al. 2010, p. 364). The Memoranda of Understanding are here seen as a unity of form and content: a form of implementation (as is, for instance, the Open Method of Coordination) of a ‘necessary’ content, which itself changes on the basis of concrete antagonistic interests. The exceptional circumstances of the ‘unprecedented crisis’ justified the Greek bail-out, but the measures accompanying the bail-out are justified as necessary to fulfil a normal—oh, so normal—obligation of EU Member States, i.e. budgetary efficiency and an economic policy coordination to achieve growth and competitiveness. The aggressive and exceptional form of the Memorandum accompanies the equally aggressive measures which enhance competitiveness through depreciation of labour.

Therein is located the necessity of the measures. Both the concrete content of these measures and their form of implementation correspond to the level of intensification of contradictions following the economic crisis, but the root of the economic policies and legislative choices of the Memoranda is found in EU ordinary decision-making. For this reason, it is pertinent to assess the EU economic principles of Growth, Competitiveness, and Employment in the White Paper (1993), with particular focus on the employment policies and labour-market regulation. The main purpose behind this document was the assertion of the need for sustained economic growth which could be achieved through ‘changes in economic and social policies and changes in the employment environment as expressed in the structure of labour market, taxation and social security incentives’. Central among these changes is the introduction of the principle of flexibility, as the more efficient means of reducing labour costs.

Lack of flexibility in labour-regulation—more particularly in terms of the organisation of working time, pay and mobility—is identified in the White Paper as the root cause of ‘what are relatively high labour costs, which have risen at a much greater rate in the Community than among our principal trading partners’ (European Commission 1993, p. 123). The main reason behind the White Paper is the assessment of the loss of competitive angle of European monopoly groups. This reason is cited as ‘a contributory factor to the loss of jobs, particularly in labour-intensive or unskilled sectors’ (European Commission 1993, p. 124); as if it is not the internationalisation of the production process itself—as manifested in the phenomenon of off-shoring—which has led businesses to move their plants to countries where labour costs are extremely low because of the de-regulation of labour, and where the conditions allow intensified exploitation in ever-worsening working conditions.

In order for EU Member States and the EU as a whole to be able to restore its international competitiveness against low-wage countries, wages have to be reduced and the level of exploitation has to increase. This is the result of the deepening of the capitalist contradictions, an essential phenomenon of which is the uneven development of the economies and the capitalist competition which leads to intensified class struggle between Capital and Labour. The need for the introduction of the class-policies of flexibility is reflected in the policies promoted in the White Paper: policies focusing on ‘removing obstacles which make it more difficult or costly to employ part-time workers or workers on a fixed-duration contract, and gearing careers more closely to the individual, or facilitating forms of progressive retirement’; on ‘reducing working hours in a period of recession’; and on ‘gearing levels of pay to company performance and productivity’ (European Commission 1993, pp. 123-131).

Flexibility is nominally aimed at countering of unemployment. However, the goal of reducing unemployment in reality stands for the true goal of reducing labour-costs, through the intensified exploitation of a wider labour-force. The reduction of unemployment, in this context, in actuality means the enhancing of the numbers of the reserve army capable of work, so as to lower the cost of labour. Part-time, temporary relations (as well as the introduction of educational schemes for the unemployed) favour the inclusion of previously excluded elements in the workforce, so that the abundance of supply and the increase of workers’ exploitation reduce the labour-costs.

Flexibility, thus, translates into measures which promote part-time and temporary contracts, and performance-related wages, through the elimination of collective bargaining and the facilitation of dismissals during a period of recession. Precisely these measures, along with the principle of flexibility, were introduced into the Greek legal system with the Second and Third Memoranda, according to the demands of the White Paper that they be reflected in national collective bargaining rules and systems (European Commission 1993, p. 124). In particular, the Second Memorandum, apart from an immediate realignment of the minimum wage level (determined by the national collective agreement) by 22% (32% for young employees), provided for the elimination of unilateral recourse to arbitration; to a maximum duration of three years for all collective contracts; and to revision of the ‘after effects’ of collective contracts (the grace period after the contract expiration is reduced to three months, after which, if a new collective agreement cannot be reached, remuneration will revert back to the basic wage).Footnote 14

These measures have had an immediate and deep impact in the fields of labour law and private sector employment. The relevant provisions of the Memoranda, annexed to N.4046/2012 Act of the Greek Parliament and implemented through ministerial decision 6/28.2.2012, amend vital parts of N.1876/1990 Act,Footnote 15 the main document of Greek collective labour law. The elimination of the ‘after effects’, as well as the rendering useless of the tool of arbitration, have caused the precipitation of the pyramid of collective agreements (Petropoulos 2012). The sectoral collective contracts of private sector employees and workers have expired and employees are forced to renegotiate individual or business contracts, with their wages forced to the minimum wage threshold.Footnote 16 Last but not least, more recent statistics show that in 2015 55.36% of the jobs created were under part-time or fixed-term contracts, whereas only 44.64% were with open-ended full-time contracts. In addition to this, 60% of the wage-earners were dismissed at least once from their jobs in 2015.

It is evident that the promotion of a flexible approach to labour law has led to the elimination of collective bargaining at the sectoral level and the proliferation of individual contracts and bargaining at the level of the enterprise. This in turn leads to the worsening of working conditions, cuts in wages, and increase of uncertainty through the increase in the absolute and relative number of part-time and temporary contracts. Therefore, we can argue that the Second and Third Memoranda are the forms of implementation of strategic class-policies, developed as early as in the White Paper of 1993. It is argued, however, that the introduction of these measures in Greece and other European countries after the crisis of 2008 is ‘necessitated’ by the uneven development of capitalist economies and the intensification of socio-economic contradictions.

Best Practices, Capitalist Unevenness and Competition

The main ratio of the Greek crisis labour legislation is to introduce flexibility into the labour market so as to restore the competitiveness of the Greek economy, through the adoption of policies prescribed in non-binding EU documents such as the White Paper of 1993. The goal of ‘competitiveness restoration’ is a result of the uneven development of the EU capitalist economies and of the capitalist competition between the different EU economies, as well as between the EU economy as a whole and other competing international economic centres (such as the U.S.A., Japan, China, etc.). The necessary result of this competition is the intensification of the contradiction of Capital versus Labour. The quest for profitability of companies, industries and national economies is intensified in periods of economic recession, and so is the competition between different capitalist economies.

This necessarily leads to the adoption of the measures which were assessed above and were introduced in the Greek legal order in the form of the Memoranda. In fact Section E. 28 of the Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies (N.4336/2015) clearly states that since

the deep structural reforms will require time to fully translate into growth and the rigidities in labour market are preventing wages from adjusting to economic conditions, upfront measures are needed to allow reduction in nominal wages so as to rapidly close the competitiveness gap.

Restoration of competitiveness and profitability is the goal behind the policies of internal devaluation, which demand further weakening of labour protection, particularly through reducing trade union power; abolishing collective bargaining on wages; facilitating the entry of women into the labour force, especially in part-time and temporary jobs; removal of barriers into certain closed professions; reducing the tax burden on capital by introducing heavier indirect taxes; introducing privatisation into the education system; and significantly raising the pension age (Lapavitsas et al. 2010, p. 364).

This standard prescription amounts to the full unfolding, and even intensification, of the underlying ideas of the European Employment Strategy (Lapavitsas et al. 2010, p. 364). Of course the adoption of these policies is not predetermined, despite the fact that it has so far been the standard prescription. Objections to whether these policies can lead to sustained growth of productivity have been voiced (see, for instance, Holland and Varoufakis 2011; Lapavitsas et al. 2010; Krugman 2012, 2015), expressing different politico-economic conceptions of capitalist growth based on public investment and (neo-)Keynesian policies. Especially in the context of the Greek crisis, these alternative views were widely debated and were central in a process of an intense contestation of the model of austerity policies prescribed so far, following Syriza’s rise to power. This process, which was also a result of intensified contradictions, revealed rifts between Greece’s main creditors, i.e. the IMF and the EU.Footnote 17

However, for reasons that fall outside the scope of our analysis, the commitment of the European Union policies of internal devaluation was confirmed once again in the Third Memorandum, which was the result of the process of negotiation which lasted for seven months and culminated in the referendum of July 2015. Act No 4336/2015, which introduced the Third Memorandum into the Greek legal system, in a verbatim quote of the Euro Summit Statement of Brussels, 12 July 2015, provides for ‘the review of the existing frameworks in labour market, including collective dismissals, collective action and collective bargaining, taking into account best practices at international and European level’ (Euro Summit 2015, my emphasis). That this review ‘should not involve a return to past policy settings which are not compatible with the goals of promoting sustainable and inclusive growth’ (Euro Summit 2015) leaves no margin of misinterpretation as to its orientation.

The recent reiteration of the commitment to prioritising the freedom of the capitalist enterprise in conducting its business over the protection that collective labour law affords the employees of a company in the Advocate General’s opinion in the AGET case is also consistent with the argument developed here.Footnote 18 It is argued that the commitment to these ‘necessary’ measures, which will lead to the restoration of competitiveness and growth by worsening the position of Labour compared to Capital, is expressed in the concept of ‘best practices’. These ‘best practices’ must be taken into account when reviewing the existing frameworks in labour market, including collective dismissals, collective action and collective bargaining. This important concept, which points towards the content of measures to be introduced in the form of the Third Memorandum, requires a comparative analysis of the labour law reforms adopted in other EU Member States.

It is a concept of importance for an additional reason: it confirms that the measures taken in the exceptional Greek predicament correspond to the general EU principles and prescribed policies. The concept of ‘best practices’ reveals the content behind the different forms through which these measures are introduced. To legislate on the basis of ‘best practices’ means to take into account the labour law reforms introduced in 2016 in France and in 2015 in Italy—i.e. in countries without Memoranda—to restore competitiveness. Therefore, it means that on the basis of uneven development and capitalist competition, the labour law legislation reaches a point of convergence necessitated by these conditions of intensified contradiction and expressed in the concept of ‘best practices’.

As a matter of fact, the means to restore the competitiveness of the French economy, prescribed in the 2016 labour law reforms, focus on the reduction of labour costs through measures which re-organise the working-hours and collective bargaining. The law brings the French model closer to the UK one, where bargaining takes place at the company level. This enables two things. On the one hand, companies have more ‘flexibility’ in deciding the terms required at each point of the economic cycle. On the other hand, the loss of mass participation in negotiations taking place at the sectoral or national level reduces the negotiating power of the employees. The prioritisation of bargaining at company rather than sectoral level is complemented with the reform of the law relating to collective dismissals. These are facilitated by the reduction of the power of judges in matters of redundancies. So far, French judges could oppose lay-offs if the parent company, even if based abroad, was profitable. In the new legislation, a French subsidiary can cut jobs if its revenues have fallen for four consecutive quarters and if it has posted operating losses for two quarters. Judges would only verify the accuracy of the financial statements and no longer delve deeper into the reasons (Chassany 2016).

The facilitation of collective redundancies and the adjustment of bargaining at company level result in the loss of negotiating power of the employees and increase the uncertainty of their working conditions by ‘raising a Damoclean sword’ over their heads. Therefore, firms are given greater freedom to intensify the exploitation of labour, by reducing pay, increasing the working-hours, negotiating holidays or maternity leave, etc. The means to restore competitiveness of the French economy are a prescription for intensification of the exploitation of labour. For this reason they were met with popular resistance and several weeks of protest. It is precisely this resistance which forced the government to pass these measures under an extra-ordinary procedure.

With regards to Italy, the main ratio behind the Jobs Act of 2015 was the re-boosting of the economy through the reduction of unemployment (which was up to 12.8% overall and 42% among workers under the age of 29) and precariousness. The policy of the Jobs Act was based on the mainstream politico-economic conception of labour market ‘rigidities’—namely, strong trade unions, generous social benefits, high minimum wages, or firing restrictions—as the main causes behind persistent unemployment and loss of competitiveness, which we saw reflected in the White Paper of 1993 (Caldwell 2015; McKay 2014; Fana et al. 2015). The Act sought to ‘improve’ the economy by establishing a more ‘flexible’ labour market which would entice employers to hire new employees by making dismissals less costly and burdensome to employers and introducing a new type of contract.

As far as collective dismissals are concerned, the Jobs Act amended Article 18 of the old legislation, which required that employers with at least 15 employees reinstate permanent employees who had been unlawfully terminated. Pursuant to the reforms, employers will only be required to reinstate employees who were unlawfully terminated for discriminatory or retaliatory reasons; and those subject to terminations which are null and void pursuant to statute, such as the termination of an employee on maternity leave, and in the case of non-written terminations. Employees subject to other unlawful terminations, such as ones for economic reasons, will only be entitled to compensatory relief, not reinstatement (Caldwell 2015).

Another measure which contributes to the freedom of enterprise of the employers is the facilitation of temporary contracts through the elimination of previous restrictions on their adoption—before the Jobs Act implementation, firms were allowed up to a maximum of 20% temporary over the total amount of contracts (Fana et al. 2015). However, a contradiction emerges between the Jobs Act’s declared intention (stimulating permanent employment) and its outcome (encouraging the diffusion of a contract type which allows extremely easy layouts) (Fana et al. 2015). The facilitation of collective redundancies means that the new permanent contract is deprived of the substantial requirements of an open-ended contract. Additionally, the data inspection shows that the Jobs Act is failing to meet its main goals of boosting employment and reducing the share of temporary and atypical contracts. Instead, an increase in the share of temporary contracts over the open-ended ones is observed, as well as a rise of part-time contracts within new permanent positions. In fact, 63% of new workers (158 out of 253,000) in the first nine months of 2015 have a temporary contract, whereas the only increase in employment detected is characterised mainly by temporary contracts signalling that the increase in permanent contracts is mostly due to the transformation of contracts’ and not to jobs’ creation (Fana et al. 2015).

Of course this tendency to proliferation of temporary contracts is the result and desired outcome of the introduction of more ‘flexibility’ in the labour market. As we saw above, this tendency is recorded in Greece too, where more than half of the new contracts in 2015 were temporary or part-time contracts. This tendency is also evident in Britain, an EU Member State which is not a member of the Eurozone. In Britain 2.5% of the labour-power is employed under zero-hour contracts, which is the most flexible form of employment.

Necessity and Contingency of Form and Content

It has been argued that austerity policies and policies of liberalisation cannot be understood if we do not consider the leading role of German capital (with its internal differentiations, of course) in the EU context. The competitive advantage of the German economy informed the EU response to the crisis, through the introduction of similar measures (which would restore competitiveness by intensifying exploitation) to other EU Member States. In this context it should be noted that the term ‘mini-job’ was coined in Germany. It is a form of marginal employment that is generally characterised as part-time with a low wage. According to the latest legislation, the monthly income of a mini-job is less than 450 Euros, exempting them from income tax (Blankenburg 2012). According to the figures of the German Employment Agency, 7.3 million Germans, or one in every five employees, held ‘mini-jobs’ in September 2010—an increase of 1.6 million since 2003. The number of workers taking ‘mini-jobs’ as additional side-jobs to make ends meet almost doubled from 1.3 million in 2003 to 2.4 million in 2010 (Blankenburg 2012).

The uneven and spasmodic character of the development of individual enterprises, of individual branches of industry and individual countries, under the capitalist system leads to intensified capitalist competition between the different enterprises, industries and countries. These class antagonisms in the form of capitalist unevenness and competition are to account for the introduction of measures for ‘flexibility’ and ‘growth’. In order for individual enterprises, industries and countries, to compete amongst themselves and with other antagonists they need to lower wages and increase exploitation. The intensification of intra-class antagonisms leads to intensification of class struggle. And the principles reflecting these tendencies are evident, for instance, in the EU policies promoting the facilitation of collective dismissals. The constituting principle of the AGET case is echoed in the labour law reforms of France, Italy and—probably—Greece.

In the EU context, capitalist unevenness is reflected in a specific intra-EU division of labour, which dates back to the beginning of the—then—European Community. This intra-EU division of labour has been one of the strategic choices in the EU’s response to competition with the USA, Japan, and more recently China and other developing economies. The choice of this intra-EU division of labour was based on the judgement that the traditional sectors of European industry are going through a crisis, while other cutting-edge sectors (microelectronics, telecommunications, biotechnologies, etc.) can guarantee constant and growing international demand, satisfactory rates of profit and a monopolised structure of productive technology (Papadopoulos 1994, pp. 30–31). Hence the powerful Member States chose to follow a methodically co-ordinated process of expanding the production of these sectors. In parallel, the least developed countries acquired the role of providing the rest of the Community with the surplus of agricultural and traditional (low technology) industrial products, as well as those of trading/transshipping centres (Papadopoulos 1994, pp. 30–31).

The Community, in this way, prioritised the economic goal of international competitiveness, while downgrading the goal of intra-European convergence of economies. The international competitiveness of the EU, as well as the intra-EU competition, is translated into the series of class-oriented policies assessed above, which worsen the condition of Labour compared to Capital. It is a necessity, then, that these policies are introduced on the basis of this intra-EU division of labour, albeit with differences as to the time and manner of their implementation, owing precisely to the unevenness of development of the EU. Thus, the EU and the Euro may facilitate the convergence of capitalist economies through the freedom of movement of capital, goods, services and labour-power, but each capitalist economy follows its own economic cycle, and the competition between them co-exists with their collaboration and is exacerbated in situations of crisis, despite their interdependence.

Of course the aim of this analysis lies far from characterising the relation between the countries occupying different positions in this division of labour as a (neo-)colonial one. In fact Greek capitalists consent to these strategic choices in the productive role of the country in this division of labour. Big industries have been demanding further measures in line with austerity and integration of the liberalisation of markets, most importantly the labour market, which would lead to profit-increase, since 1992 (Papadopoulos 1994, pp. 30–31). A determining factor for this consensus is the strategic choice of Greek capital for fast and easily attainable profits through the lowering of labour costs, without further investing in technological updating or reorientation towards the production of high technology.

Consequently, the ‘necessity’ of the Greek crisis legislation is here proven to be relative to its class-orientation. The Memorandum is the form of implementation of the strategic choices of (Greek and European) Capital in the Greek legal system. Based on fundamental EU principles, the Memoranda and the laws implementing them do not constitute an exceptional or extra-EU commitment, but an execution on behalf of the Member State of their EU obligations. These obligations secure the reproduction of capitalist productive relations in their intensified form; demands which existed before the crisis. In fact, various analyses have shown that even before the crisis, ‘proponents of laissez-faire approaches (including the IMF, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and World Bank) had urged Greek governments to promote far-reaching labour market reforms’ (Dedousopoulos 2012). These recommendations were ‘usually in line with the collective bargaining demands of the largest employers’ association in Greece, the Hellenic Federation of Enterprises (SEV), over the past two decades’ (Dedousopoulos 2012).

Examining the socio-economic content of the measures allows us to see their ‘necessary’ character; a necessity corresponding to the objective socio-economic contradictions of capitalism. Uneven development and capitalist competition generate demands for restoring competitiveness and profitability, through reduction of labour-costs and intensification of exploitation; a demand that, during a capitalist crisis, is expressed in many and different forms because of the intensification of social (not only class, but also intra-class) antagonisms. Every capitalist crisis brings with it the need for destruction of capital and productive forces. This need is expressed in policies of ‘internal devaluation’ and reduction of labour costs.

The dismantling of the system of collective bargaining and arbitration, introduced with the Second Memorandum, is in line with the policy of ‘internal devaluation’ and, thus, reflects this fundamental need of capital. In fact, the structural reforms undertaken in line with the loan agreements have been based upon the assessment that Greece had some of the strictest employment protection legislation amongst the OECD countries and was, therefore, in dire need of a more ‘flexible’ system of labour law on its way back to ‘growth’ (Koukiadaki and Kretsos 2012, p. 279). This ‘flexible system’, as concretised, among others, through the elimination of unilateral recourse to arbitration and the confinement of arbitration only to the determination of the basic wage/salary (excluding the introduction of any provisions on bonuses, allowances or other benefits) was consistent with SEV’s argument that compulsory arbitration should be abolished so as to allow negotiations to be ‘better aligned with reality’ (Koukiadaki and Kretsos 2012, p. 276).

Therefore, both form and content ‘in the last instance’ serve to introduce measures which worsen the condition of Labour compared to Capital, and are necessitated by the capitalist unevenness and competition, which is intensified in situations of crisis. Therein lies their ‘necessity’: in their class-orientation. As a result, the invocation of the ‘general interest’ by the bourgeois authorities serves in reality to obscure the intensification of exploitation and the class-orientation of the measures. In reality, the conflicting social interests of different social classes cancel out the generality of the concept of general interest. But, simultaneously, precisely because of its class-orientation and its response to intensified (class and intra-class) contradictions, the Greek crisis legislation has to assume the form of the Memorandum and use the language of necessity.

However, neither is the content of those necessary measures fixed, nor is the form of their implementation; this is due to the contingent nature of the developing contradictions. Form and content are contingent upon the intensification of these contradictions. Their specificity is determined by the level of intensification of social antagonisms, i.e. class struggle and intra-class conflict. The analysis so far has not been based on a mechanistic materialism, but rather on a dialectical one, mindful of the contradictory movement of social, economic and political reality. Legislation is not seen as the necessary reflection of the one-sided interests of a ruling class which acts as a metaphysical subject. On the contrary, we have focused on the existence of objective contradictions intensified by the development of capitalist antagonisms, which inform the principles deployed to deal with a crisis, and the form assumed in the exercise of these powers.

It has already been noted above that the policies of ‘internal devaluation’ do not come without adverse effects for the functioning of the capitalist market, as they lead to the hindering of demand, consumption and the valorisation of surplus-value. Of course, this understanding furthers the need for a Marxist analysis of legislation and its content. The many-sided analysis of the relation between these principles would involve a thorough scrutiny of the intra-capitalist contradictions, but this analysis lies outside the scope of this paper. Suffice to say that the different interests between states, but also the different interests of different sectors of monopoly groups and multinational enterprises within the states themselves, give rise to different approaches as to which set of policies and what level of decision-making will serve these interests better.

The content of the measures itself is, therefore, dynamic and reflects the contradictory development of the capitalist relations of production. So, the fact that austerity and policies of internal devaluation have been so far the prescribed policies of capital for recovery from the crisis does not mean they constitute the only way out for monopoly interests. For the reasons examined above, which relate to the profitability and competitiveness of capitalist economies, the content of the measures has so far been based on the prioritisation of policies of internal devaluation over policies of investment and providing the market with stimulus.

Nevertheless, the programme of quantitative easing promoted by the ECB has been pointing to another direction. This tendency might be reinforced by the recent report from the OECD which calls for less austerity and more public investment which would boost demand,Footnote 19 on the basis of its assessment for weak global growth in 2016–2017. Of course this will not necessarily entail the amelioration of the conditions for intensified exploitation of labour. According to the OECD, much more progress is needed in the EU with regards to ‘structural’ reforms in order to boost investment and productivity. Capital is invested where the conditions for profit-making are more favourable, i.e. where the conditions for the extractions of surplus value are more favourable.

The above is evidence of the role played by intra-class antagonisms (which include not only intra-national conflicts but also intra-EU and international antagonisms) over the content of the measures which can lead to the most profitable way out of the crisis, as well as of the role of the different levels of resistance presented by the working-class and social movements in each country, in influencing the content of the legislation as well as the form of its implementation.

If the content of the ‘necessary’ measures is not fixed, but corresponding to the level of intensification of social antagonisms, neither is the form of their implementation. A point to be raised with regards to both the ‘necessity’ of the measures and the contingency of their form of implementation is that such class-oriented measures are introduced in all EU countries, on the occasion of the capitalist crisis and the inability to foresee growth at any point in the future. In these countries these ‘necessary’ measures are introduced, despite the absence of ‘Memoranda’, albeit in different forms in each of them. In France, for instance the labour law reforms met with strong resistance by the working-class and the popular strata, and the reforms were adopted with the use of an extra-ordinary procedure. This point confirms the need for a different kind of analysis, a dialectical analysis of form in its unity with content, if we are to assess these measures in a critical manner.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper has offered a dialectical materialist analysis of the Greek crisis legislation. The form and content of this legislation has been examined in its movement and mutual relation to social and economic contradictory processes, such as capitalist unevenness and competition. In this context the principles used by the judiciary and the law-making mechanisms (of the European Union and the Greek government) to legislate in the context of a crisis-ridden Greece after 2010 were examined. It is argued that the formal justification of the measures of the Greek crisis legislation as necessary (to counter unemployment and restore growth and competitiveness, through the introduction of flexibility, i.e. deregulation of labour market, or rather regulation of labour market in a way that benefits enterprises as opposed to the employees) is masquerading the brutal reality of the need of capital to intensify the exploitation of the workers, so as to restore competitiveness and profitability.

Additionally, the unity of fundamental EU monetary (budgetary efficiency) and economic (growth and competitiveness) principles and policies reveals the class-orientation of policies of growth and competitiveness and their introduction in a process of deepening antagonisms, capitalist competition and class struggle. Nevertheless, ultimately the form and the content of the measures themselves are contingent, necessitated by the intensification of capitalist contradictions. The form and content of the Memoranda responds to the extraordinary circumstance of the global crisis, while acting as a mediator with a view to satisfying the ordinary—oh, so ordinary—need of the monopolies, found and proclaimed in EU documents throughout the life of the EU.

The reference to class struggle as a negating process renders the above analysis dynamic, by anchoring it in the reality of economic, social and political praxis. The outcome of legislation is not pre-determined. The legal form and content is contingent upon the clash of social forces. Austerity might be replaced by ‘New-Deal’ policies concentrating on fiscal stimuli and public investment. The recent forecasts for anaemic growth over the next years might prompt the EU and national authorities to prescribe a different ‘pharmakon’ for the resolution of the irresoluble capitalist contradictions. Measures of a different content will be promoted then. Last but not least, these measures might be introduced through a new mechanism of implementation; a mechanism based on the principle of the ‘ever-closer Union’. Whether a ‘pharmakon’ of a different form and content can be a cure rather than poison remains doubtful, but it will ultimately depend on the development of capitalist contradictions.

Notes

Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union (otherwise known as the ‘Fiscal Compact’).

See for instance Fredric Jameson’s warning against viewing the dialectics as a method, because such conception ‘necessarily carries within itself [a radical opposition] between means and ends. If the dialectic is nothing but a means, what can be its ends? If it is a metaphysical system, what possible interest can it claim after the end of metaphysics?’ (Jameson 2009).

Article 109 of the Standing Orders of the Greek Parliament provides that ‘if a bill is characterised as urgent, it is processed and examined in one sitting’, while ‘the debate and passage of the urgent bill is concluded in one meeting which cannot last more than ten hours’. Furthermore, the process of ratification of an Act by the Parliament is characterised as interna corporis, and as a result is not subject to judicial review.

These concerns are reflected in a Report conducted by J.P. Morgan Chase on the process of adjustment of the Euro-area economies to the crisis, where Southern European Constitutions are seen as aberrations to the EU social acquis and as obstacles to growth and competitiveness. According to the report: ‘The crisis has made apparent that there are deep seated political problems in the periphery, which need to change if EMU is going to function properly in the long run. Constitutions tend to show a strong socialist influence, reflecting the political strength that left wing parties gained after the defeat of fascism. Political systems around the periphery typically display several of the following features: weak executives; weak central states relative to regions; constitutional protection of labour rights; consensus building systems which foster political clientelism; and the right to protest if unwelcome changes are made to the political status quo’ (Mackie and Barr 2013, my emphasis).

Indicatively see R (Bancoult) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2008] UKHL 61 [109]; R (Corner House Research) v Director of the Serious Fraud Office [2008] UKHL 60 [23]; R (Abbasi) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2002] EWCA Cic 1598; as well as Thomas Poole’s assessment of the above cases under the prism of the category of ‘reason of state’ (Poole 2015, pp. 262–291).

See R (Bancoult) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2008] UKHL 61 [130].

Relative autonomy is a central concept for the Marxist analysis of state and law. It is necessary for the state to act as a factor of cohesion and consolidation of class power (intra-class aspect), as well as for the effective exercise of class rule (class aspect). As E.P. Thompson puts it with regards to the latter, the essential precondition for the effectiveness of law, in its function as ideology, is that it shall display an independence from gross manipulation and shall seem to be just; if the law is evidently partial and unjust, then it will mask nothing, legitimise nothing, contribute nothing to any class’s hegemony (Thompson 2013, p. 263). Along the same lines with regards to the former, according to Poulantzas, capitalist law appears as ‘the necessary form of a State that has to maintain relative autonomy of the fractions of a power-bloc in order to organize their unity under the hegemony of a given class or fraction’ (Poulantzas 2000, p. 91).

See paragraph 35 of Judgment 668/2012 of the Greek Council of State.

See case Flaminio Costa v ENEL (1964).

One could argue that the ultimate EU necessity, i.e. the primary goal, is fiscal stability. A principle-necessity which the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union sought to give binding force to, by requiring its ‘taking effect in the national law of the Contracting Parties through provisions of binding force and permanent character, preferably constitutional’ (Article 1, paragraph 2).

Paragraph 137 of the Pringle decision (Pringle 2012) reads: ‘Article 125 TFEU does not prohibit the granting of financial assistance by one or more Member States to a Member State which remains responsible for its commitments to its creditors provided that the conditions attached to such assistance are such as to prompt that Member State to implement a sound budgetary policy’ (my emphasis).

See paragraph 36 of Greek Council of State Decision 2307/2014.

Section E.28 of the Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies.

N.1876/1990 was ratified unanimously as an organic part of the Greek Constitution concerning collective bargaining (Petropoulos 2012).

According to data from the Labour Inspectorate, until the end of May 2012, 84,772 individual contracts had been submitted with an average earnings decline of 23.5%, as well as another 400 business contracts for 30,659 employees with an average pay cut of 24% (Inspectorate of Labour 2012).

A central point of disagreement, which showcases the intensified contradictions over the Greek programme and to an extent over the future of the Union, is the issue of the sustainability of the Greek debt. The IMF report on the sustainability of the Greek debt suggests the adoption of further measures of debt relief, a prospect strongly resisted by the EU. Notwithstanding this point of disagreement, the IMF’s report reiterates the mainstream commitment to measures that safeguard the reproduction of the capitalist productive relations by reforming the legislation on collective dismissals and industrial action and worsening the position of Labour compared to Capital. In the report we read: ‘As to broader structural reforms, the further postponement of reforms to the collective dismissals and industrial action frameworks to the fall of 2016—overdue since 2014—and the still extremely gradual pace at which Greece envisages to tackle its pervasive restrictions in product and service markets are also not consistent with the very ambitious growth assumptions used hitherto’ (IMF 2016, my emphasis).

Of course, it remains to be seen whether this commitment materialises into concrete policies. The concrete policies relating to this aspect of structural reforms of the Third Memorandum had not been introduced at the time of writing these lines. The process of consultation between different social partners had begun, but the actual materialisation of these policies would depend on the resistances met, either in the form of class struggle and popular resistance, or in the form of intra-class and intra-EU contradictions over the prescribed measures to deal with the general forecasts for anaemic growth in 2016 and the repercussions of the British vote to leave the EU in the referendum of 23 June 2016.