Abstract

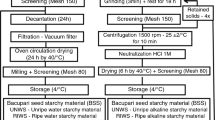

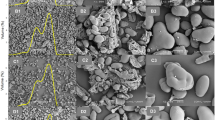

Starch was isolated from the seeds of ripe and unripe fruits of achachairu (Garcinia humilis) using three extraction methods: neutral, using distilled water at pH 7.0, acid, using ascorbic acid solution at pH 4.0, and alkaline, using sodium hydroxide solution at pH 10.0. After extraction, the starches were characterized in terms of proximate composition and antioxidant, morphological, structural, thermal and spectrometric properties. In general, the highest starch yield was observed for neutral extraction, although the morphological structure and proximate composition revealed higher purity for the starch obtained by acid extraction. Starches obtained from mature matrices can be characterized as products with a high-amylose content, as they resulted in amylose contents greater than 50%. However, alkaline extraction, in addition to promoting greater agglomeration and damaged starch, is also related to the reduction in amylose–lipid complexes. The viscosity parameters of the starches confirmed their apparent levels of amylose, mainly those extracted from mature seeds. Starches also showed antioxidant activity, especially those obtained by neutral extraction, since the highest total phenolic content was determined in this sample, while the other extractions (acid and alkaline) showed results according to method affinity for antioxidant activity. The results suggest that the attributes of the starches found in achachairu seeds make them viable for use in several applications, mainly in the development of biodegradable films, especially for starches obtained in neutral extraction, whose rheological characteristics proved to be favorable for this application.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hornung PS, Oliveira CS de, Lazzarotto M, Lazzarotto SR da S, Schnitzler E. Investigation of the photo-oxidation of cassava starch granules: Thermal, rheological and structural behaviour. J Thermal Anal Calorimetry. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-015-4706-x

Sangseethong K, Termvejsayanon N, Sriroth K. Characterization of physicochemical properties of hypochlorite and peroxide oxidized cassava starches. Carbohyd Polym. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.05.003.

de Oliveira CS, Andrade MMP, Colman TAD, da Costa FJOG, Schnitzler E. Thermal, structural and rheological behaviour of native and modified waxy corn starch with hydrochloric acid at different temperatures. J Thermal Anal Calorimetric. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-013-3307-9.

Barbosa MC. Efeito da adição de proteína nas propriedades físicas e reológicas dos géis obtidos a partir de amido de semente de jaca (Artocarpus Integrifólia). Dissertação (Mestrado em Engenharia de Alimentos) – Itapetininga: Universidade Estadual do Sudoesta da Bahia – UESB; 2013. pp. 91.

Kim YS, Wiesenborn DP, Orr PH, Grant LA. Screening potato starch for novel properties using differential scanning calorimetry. J Food Sci. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.1995.tb06292.x.

Pinto VZ, Vanier NL, Deon VG, Moomand K, El Halal SLM, Zavareze EDR, Lim LT, Dias ARG. Effects of single and dual physical modifications on pinhão starch. Food Chem. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.037.

Wang X, Chen L, Li X, Xie F, Liu H, Yu L. Thermal and rheological properties of breadfruit starch. J Food Sci. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01888.x.

Maniglia BC, Tapia-Blácido DR. Isolation and characterization of starch from babassu mesocarp. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.11.001.

Alcázar-alay SC, Angela M, Meireles A. Physicochemical properties, modifications and applications of starches from different botanical sources. Food Sci Technol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-457X.6749.

Villarreal ME, Ribotta PD, Iturriaga LB. Comparing methods for extracting amaranthus starch and the properties of the isolated starches. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2012.11.009.

Nogueira GF, Fakhouri FM, Oliveira RA de. Extraction and characterization of arrowroot (Maranta arundinaceae L.) starch and its application in edible films. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.024

Silva HR da, Assis D da C de, Prada AL, Silva JOC, Sousa MB, Ferreira AM, Amado JRR, Carvalho H de O, Santos AVT de LT, Carvalho JCT. Obtaining and characterization of anthocyanins from Euterpe oleracea (açaí) dry extract for nutraceutical and food preparations. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjp.2019.03.004

Molin MMD, Silva S, Alves DR, Quintão NLM, Monache FD, Filho VC, Niero R. Phytochemical analysis and antinociceptive properties of the seeds of garcinia achachairu. Arch Pharmacal Res. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12272-012-0405-3.

Cury GC, Gisbert MCA, Porcel WJR. Um estudo da fruta comestível de Garcinia gardeneriano. Revista Boliviana de Química, La Paz- Bolívia. 2016. https://doi.org/10.32404/rean.v4i5.2189

Bagattoli PCD. Phytochemical profile and evaluation of antioxidant and cytotoxicity activity of fruits from the flora of the state of Santa Catarina (SC), Brazil. Dissertação (Mestrado em Produtos Naturais e Substâncias Bioativas) – Itajaí: Universidade do Vale do Itajaí; 2013. pp. 123.

Virgolin LB, Seixas FRF, Janzantti NS. Composition, content of bioactive compounds, and antioxidant activity of fruit pulps from the Brazilian Amazon biome. Pesqui Agropecu Bras. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-204X2017001000013.

Hornung PS, Ávila S, Lazzarotto M, Lazzarotto SR da S, Siqueira GL de A, Schnitzler E, Ribani RH. Enhancement of the functional properties of Dioscoreaceas native starches: Mixture as a green modification process. Thermochimica Acta. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tca.2017.01.006

Wang YJ, Chong SW. Effect of pericarp removal of wet-milled corn starch. Cereal Chem. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1094/CC-83-0025.

AOAC, American association of official analytical chemists. Official methods of analysis ofthe American association ofofficial analytical chemists. USA: Gaithersburg; 2000.

Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959. https://doi.org/10.1139/o59-099.

Martínez C, Cuevas F. Evaluación de la calidad culinaria y molinera del arroz. Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT). 1989. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Pantelić MM, Dabić Zagorac D, Davidović SM, Todić SR, Bešlić ZS, Gašić UM, Tešić ŽL, Natić MM. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds in berry skin, pulp, and seeds in 13 grapevine varieties grown in Serbia. Food Chem. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.05.051.

Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventós RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1974; 1998. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99017-1

Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci Technol. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5.

Benzie I, Strain J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “Antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay analytical biochemistry. Anal Biochem. 1996. https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.1996.0292.

Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biol Med. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3.

Ravi R, Manohar RS, Rao PH. Use of Rapid Visco Analyser (RVA) for measuring the pasting characteristics of wheat flour as influenced by additives. J Sci Food Agric. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199909)79:12%3c1571::AID-JSFA400%3e3.0.CO;2-2.

International Association for Cereal Science and Techonology - ICC, Schwechat, Austria. 1995. Retrivied from: https://www.infona.pl/resource/bwmeta1.element.baztech-article-BPOA-0013-0017. Accessed 6 Jan 2021.

Abdel-Aal ESM, Hernandez M, Rabalski I, Hucl P. Composition of hairless canary seed oil and starch-associated lipids and the relationship between starch pasting and thermal properties and its lipids. LWT. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109257.

Tester RF, Yousuf R, Kettlitz B, Röper H. Use of commercial protease preparations to reduce protein and lipid content of maize starch. Food Chem. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.041.

Brasil. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária – RDC 263 de 22 de setembro de 2005. Regulamento Técnico Para Produtos de Cereais, Amidos, Farinhas e Farelos

Damodaran S, Parkin KL, Fennema OR. Química de Alimentos de Fennema, 4th ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2010.

Singha KT, Sreeharsha RV, Mariboina S, Reddy AR. Dynamics of metabolites and key regulatory proteins in the developing seeds of Pongamia pinnata, a potential biofuel tree species. Ind Crops Prod. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111621.

Lineback DR. The starch granule: organization and properties. Bakers Digest; 1984. pp. 16–21.

Wu J, Wang X, Ma S. Study on Changes in the characteristics of key carbohydrates in wheat during the after-ripening period. Grain Oil Sci Technol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1447.gost.2018.18012.

Collona P, Leloup V, Buléon A. Limiting factors of starch hydrolysis. Euro J Clin Nutrition. 1992. https://europepmc.org/article/med/1330526

Parker R, Ring SG. Aspects of the physical chemistry of starch. Adv Carbohydr Chem. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0096-5332(08)60122-8.

Maieves HA, López-Froilán R, Morales P, Pérez-Rodríguez ML, Ribani RH, Cámara M, Sánchez-Mata MC. Antioxidant phytochemicals of Hovenia dulcis Thunb. peduncles in different maturity stages. J. Funct. Foods. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2015.01.044

Sampaio CRP, Hamerski F, Ribani RH. Antioxidant phytochemicals of Byrsonima ligustrifolia throughout fruit developmental stages. J Funct Foods. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2015.08.004.

Mali S, Grossmann MVE, Yamashita F. Filmes de amido: produção, propriedades e potencial de utilização. Semina: Ciências Agrárias. 2010. https://doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2010v31n1p137

Iahnke AOES, Costa TMH, Rios A de O, Flôres SH. Antioxidant films based on gelatin capsules and minimally processed beet root (Beta vulgaris L. var. Conditiva) residues. J Appl Polymer Sci. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.43094

Crizel T de M, Rios A de O, Alves V, Bandarra N, Moldão-Martins M, Flôres SH. Active food packaging prepared with chitosan and olive pomace. Food Hydrocolloids. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.08.007

Torres-León C, Vicente AA, Flores-López ML, Rojas R, Serna-Cock L, Alvarez-Pérez OB, Aguilar CN. Edible films and coatings based on mango (var. Ataulfo) by-products to improve gas transfer rate of peach. LWT. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2018.07.057

Ferreira MSL, Fai AEC, Andrade CT, Picciani PH, Azero EG, Gonçalves ÉCBA. Edible films and coatings based on biodegradable residues applied to acerolas (Malpighia punicifolia L.). J Sci Food Agric. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.7265

Andrade RMS, Ferreira MSL, Gonçalves ÉCBA. Development and characterization of edible films based on fruit and vegetable residues. J Food Sci. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.13192.

Adilah AN, Jamilah B, Noranizan MA, Hanani ZAN. Utilization of mango peel extracts on the biodegradable films for active packaging. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2018.01.006.

Zainuddin SYZ, Ahmad I, Kargarzadeh H. Cassava starch biocomposites reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals from kenaf fibers. Compos Interfaces. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1080/15685543.2013.766122.

Hoover R. Composition, molecular structure, and physicochemical properties of tuber and root starches: A review. Carbohyd Polym. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0144-8617(00)00260-5.

Li G, Zhu F. Amylopectin molecular structure in relation to physicochemical properties of quinoa starch. Carbohyd Polym. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.02.014.

Singh N, Singh J, Kaur L, Sodhi NS, Gill BS. Morphological, thermal and rheological properties of starches from different botanical sources. Food Chem. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00416-8.

Palacios-Fonseca AJ, Castro-Rosas J, Gómez-Aldapa CA, Tovar-Benítez T, Millán-Malo BM, Del Real A, Rodríguez-García ME. Effect of the alkaline and acid treatments on the physicochemical properties of corn starch. CYTA J Food. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1080/19476337.2012.761651.

Silveira TMG, Tápia-Blácido DR. Is isolating starch from the residue of annatto pigment extraction feasible? Food Hydrocolloids. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.09.027.

Suortti T, Gorenstein MV, Roger P. Determination of the molecular mass of amylose. J Chromatogr A. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9673(98)00831-0.

Rodriguez-Garcia ME, Hernandez-Landaverde MA, Delgado JM, Ramirez-Gutierrez CF, Ramirez-Cardona M, Millan-Malo BM, Londono-Restrepo SM. Crystalline Structures of the main components of Starch. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2020.10.002.

Hsien-Chih HW, Sarko A. The crystal structure of A-starch: is it double helical? Carbohydr Res. 1977. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-6215(00)80566-2.

Hsien-Chih HW, Sarko A. The double-helical molecular structure of crystalline a-amylose. Carbohydr Res. 1978. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-6215(00)84464-X.

Lima BNB, Cabral TB, Neto RPC, Tavares MIB, Pierucci APT. Characterization of commercial edible starch flours. Polimeros. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-14282012005000062.

Souza RCR, Andrade CT. Investigação dos processos de gelatinização e extrusão de amido de milho. Polímeros. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-14282000000100006.

Xu R. Investigation on after-ripening mechanism of wheat. Zhengzhou: Henan University of Technology. 2013. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1447.GOST.2018.18012

Weber FH, Collares-Queiroz FP, Chang, YK. Caracterização físico-química, reológica, morfológica e térmica dos amidos de milho normal, ceroso e com alto teor de amilose. Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos [online]. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-20612009000400008

Soliman AAA, El-Shinnawy NA, Mobarak F. Thermal behaviour of starch and oxidized starch. Thermochim Acta. 1997. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0040-6031(97)00040-3.

Rodrigues SC, da Silva AS, de Carvalho LH, Alves TS, Barbosa R. Morphological, structural, thermal properties of a native starch obtained from babassu mesocarp for food packaging application. J Market Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.11.030.

Aggarwal P, Dollimore D. A thermal analysis investigation of partially hydrolyzed starch. Thermochim Acta. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0040-6031(98)00355-4.

Adebowale KO, Afolabi TA, Olu-Owolabi BI. Functional, physicochemical and retrogradation properties of sword bean (Canavalia gladiata) acetylated and oxidized starches. Carbohyd Polym. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2005.12.032.

Micić DM, Ostojić SB, Simonović MB, Pezo LL, Simonović BR. Thermal behavior of raspberry and blackberry seed flours and oils. Thermochim Acta. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tca.2015.08.017.

Lawal OS. Studies on the hydrothermal modifications of new cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) starch. Int J Biol Macromol. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2005.12.016.

Morrison WR. Starch lipids and how they relate to starch granule structure and functionality. Cereal Food World. 1995; pp. 437–446.

Vandeputte GE, Vermeylen R, Geeroms J, Delcour JA. Rice starches. I. Structural aspects provide insight into crystallinity characteristics and gelatinisation behaviour of granular starch. J Cereal Sci. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0733-5210(02)00140-6

Cai J, Man J, Huang J, Liu Q, Wei W, Wei C. Relationship between structure and functional properties of normal rice starches with different amylose contents. Carbohyd Polym. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.02.067.

Zou J, Xu MJ, Wen LR, Yang B. Structure and physicochemical properties of native starch and resistant starch in Chinese yam (Dioscorea opposita Thunb.). Carbohydrate Polymers. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116188

Hu X, Huang Z, Zeng Z, Deng C, Luo S, Liu C. Improving resistance of crystallized starch by narrowing molecular weight distribution. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105641.

Eliasson AC. Carbohydrates in food. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1996. p. 664.

Cooke D, Gidley MJ. Loss of crystalline and molecular order during starch gelatinisation: origin of the enthalpic transition. Carbohyd Res. 1992. https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-6215(92)85063-6.

Beninca C, Demiate IM, Lacerda LG, Filho MASC, onashiro M, Schnitzler E. Thermal behavior of corn starch granules modified by acid treatment at 30 and 50 °C. Eclética Química. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-46702008000300002

Noda T, Tsuda S, Mori M, Takigawa S, Matsuura-Endo C, Saito K, Mangalika WHA, Hanaoka A, Suzuki Y, Yamauchi H. The effect of harvest dates on the starch properties of various potato cultivars. Food Chem. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.09.035.

Madsen MH, Christensen DH. Changes in viscosity properties of potato starch during growth. Starch/Stärke. 1996. https://doi.org/10.1002/star.19960480702.

Lui Q, Weber E, Currie V, Yada R. Physicochemical properties of starches during potato growth. Carbohyd Polym. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0144-8617(02)00138-8.

Acosta-Osorio AA, Herrera-Ruiz G, Pineda-Gómez P, Cornejo-Villegas MA, Martínez-Bustos F, Gaytán M, Rodríguez-García ME. Analysis of the apparent viscosity of starch in aqueous suspension within agitation and temperature by using rapid visco analyzer system. Mech Eng Res. 2011. https://doi.org/10.5539/mer.v1n1p110

Quemada D. Rheology of concentrated disperse systems: II. A model for non-newtonian shear viscosity in steady flows. Rheological Acta. 1978. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01522036

Quemada D. Rheology of concentrated disperse systems: III. General features of the proposed non-newtonian model. Comparision with experimental data. Rheological Acta. 1978. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01522037

Zeng M, Morris CF, Batey IL, Wrigley CW. Sources of variation for starch gelatinization, pasting, and gelation properties in wheat. Cereal Chem. 1997. https://doi.org/10.1094/CCHEM.1997.74.1.63.

OroI T, Limberger VM, M.Z. Miranda MZ de, Richards NSPS, Gutkoski LC, Francisco A de. Pasting properties of whole and refined wheat flour blends used for bread production. Ciência Rural. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782013005000026

Ragaee S, Abdel-Aal ESM. Pasting properties of starch and protein in selected cereals and quality of their food products. Food Chem. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.12.012.

Perera C, Hoover R. Influence of hydroxypropylation on retrogradation properties of native, defatted and heat-moisture treated potato starches. Food Chem. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00130-7.

Marcon MJA, Avancini SRP, Amante ER. Propriedades químicas e tecnológicas do amido de mandioca e do polvilho azedo. Florianópolis: Editora da UFSC; 2007.

Silverstein R, Webster F. Identificaçao Espectrofotométrica de Compostos Organicos, Livros Tecnicos e Científicos Editora: AS, 6a Edição; 2006. pp. 67–135.

Wang N, Zhang X, Han N, Bai S. Effect of citric acid and processing on the performance of thermoplastic starch/montmorillonite nanocomposites. Carbohyd Polym. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2008.09.021.

Tapia-Blácido DR, Sobral PJA, Menegalli FC. Potential of Amaranthus cruentus BRS Alegria in the production of flour, starch and protein concentrate: Chemical, thermal and rheological characterization. J Sci Food Agric. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.3946.

Leão DP, Franca AS, Oliveira LS, Bastos R, Coimbra MA. Physicochemical characterization, antioxidant capacity, total phenolic and proanthocyanidin content of flours prepared from pequi (Caryocar brasilense Camb.) fruit by-products. Food Chem. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.027

Zhang SD, Zhang YR, Zhu J, Wang XL, Yang KK, Wang YZ. Modified corn starches with improved comprehensive properties for preparing thermoplastics. Starch/Staerke. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1002/star.200600598.

Kizil R, Irudayaraj J, Seetharaman K. Characterization of irradiated starches by using FT-Raman and FTIR spectroscopy. J Agric Food Chem. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf011652p.

Pelissari FM, Andrade-Mahecha MM, Sobral PJDA, Menegalli FC. Isolation and characterization of the flour and starch of plantain bananas (Musa paradisiaca). Starch/Staerke. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/star.201100133.

Vicentini NM, Dupuy N, Leitzelman M, Cereda MP, Sobral PJDA. Prediction of cassava starch edible film properties by chemometric analysis of infrared spectra. Spectrosc Lett. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1080/00387010500316080.

Mendes FM. Produção e Caracterização de Bioplásticos a partir de Amido de Batata, Poster session presentation at the meeting of 10°. Congresso Brasileiro de Polímeros: Maringá; 2009.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Post-Graduation Program in Food Engineering (Federal University of Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil) for the support provided and achachairu producer Edgar Gessner, who provided the fruits used in this study.

Funding

The research was financially supported by CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) granted to M. Ikeda (Grant number 88882.381643/2019–01); and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development to R. H. Ribani (Grant number 432361/2018–9).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MI involved in conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing and project administration. BPC involved in conceptualization, software, formal analysis, investigation and writing—review and editing. AMM involved in methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, and writing—review and editing. IAEP involved in formal analysis, investigation and writing—review and editing. RHR involved in conceptualization, validation, resources, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualization and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ikeda, M., Costa, B.P., de Melo, A.M. et al. Impact of the ripening process and extraction method on the properties of starch from achachairu seeds. J Therm Anal Calorim 148, 4151–4169 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-023-12034-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-023-12034-2