Abstract

The synthesis and characterization of luminescent hybrid composites based on bisphenol A glycerolate (1 glycerol/phenol) diacrylate (BPA-Acr) as a cross-linking monomer and N-vinylpyrrolidone (NVP) as an active diluent, in the presence of UV initiator (Irgacure 651), are presented. Eu(III) and Tb(III) carboxylate complexes were added as luminescent components of composites. In their preparation, a constant concentration of the initiator (1%) and the BPA-Acr to NVP (10:3) ratio were applied. The structures of the obtained materials were confirmed by the infrared spectra (ATR-FTIR). Thermal properties of the cross-linked products were determined by different thermal analysis methods in air and nitrogen (TG–DTG–DSC and TG–FTIR). Thermal stability, pathways of thermal decomposition and volatile products of degradation were determined. Photoluminescence properties of the lanthanide complexes and the obtained composites were established. These materials can have the potential application as coatings filtering harmful UV radiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The synthesis of hybrid materials by the combination of organic polymers with inorganic compounds has been intensively investigated in recent years to obtain products of specific and unique properties [1]. Generally, organic (polymeric) materials are characterized by great flexibility and processability, while inorganic ones often exhibit an excellent heat resistance and non-inflammability. Due to such combinations, the hybrid materials possess properties not possessed by precursors, e.g., flexibility, and, at the same time, they are characterized by high mechanical strength and thermal stability. Owing to their advanced properties, the organic–inorganic hybrid materials find extensive application in topical fields like chemical sensors, optoelectronics, laser systems, environmental protection medicine, etc. [2,3,4,5].

Recently, much attention has been paid to the production of organic and inorganic nanocomposites. The introduction of inorganic nanoparticles into the polymer matrix permits obtaining new, high-quality materials of desired properties. The advantage of these systems is that the nanofiller and polymer matrix interact with each other at the molecular level. Additionally, the nanofiller added even in a small amount can significantly change the selected properties of nanocomposites. The commonly used inorganic fillers are non-metal oxides (e.g., SiO2), metal oxides (e.g., TiO2, ZnO, Al2O3), metal particles (e.g., Au, Ag, Al, Fe) and many others [6].

The main methods of synthesis of organic–inorganic nanocomposites include mixing method, sol–gel process, in situ polymerization and in situ preparation of nanoparticles in a polymer matrix [6]. Both macro- and nanocomposites are characterized by large stiffness, strength and thermal stability. However, in the case of nanocomposites their properties are much better even with very low nanofiller contents [7]. It is clearly visible in the case of mechanical (Young’s modulus, impact strength, scratch resistance) and thermal (stability and conductivity) properties [7,8,9,10].

A large number of organic and inorganic materials allow to create an unlimited amount of hybrid materials whose properties and application will mostly depend on the applied materials [11]. For the synthesis of organic–inorganic hybrid materials characterized by photoluminescence and thermal properties, the lanthanide complexes are commonly applied [2, 3, 12, 13].

The most intensively investigated lanthanide complexes used as dopants for different types of hosts are molecular chelates based on β-diketone ligands [14]. The main advantages of such compounds are ligands’ commercial availability, easy synthesis and excellent luminescence properties. Another significant group of lanthanide complexes incorporated into different hosts are those based on the carboxylate ligands [15]. Embedding such kind of lanthanide complexes in the matrices is first of all beneficial for their thermal properties. Lanthanide carboxylate complexes exhibit thermal stability compared to those based on other ligands. This feature is very important from a practical point of view because in most cases their addition improves chemical and thermal stability of hybrid materials. Owing to the growing importance of materials based on polymeric matrices doped with lanthanide complexes, their investigations are very perspective [16,17,18]. It is worth to mention that carboxylate ligands very often play a role of “antenna” which effectively transfers absorbed energy to lanthanide ions making electron forbidden f–f transitions of Ln(III) ions more efficient [3].

Photoluminescent properties of polymeric material derivatives of naphthalene 2,7-diol were the subject of our earlier research [19, 20]. However, due to the high absorption of the radiation, the use of UV curing method for these copolymers was impossible.

The objective of our investigations is to develop a method of photoluminescent hybrid composite synthesis in the thin layer form. As an organic matrix, the mixture of two reactive monomers, bisphenol A glycerolate diacrylate and N-vinylpyrrolidone, was used. Photopolymerization of the compositions with the use of the UV initiator (2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenyl-acetophenone) and different amounts of Eu(III) and Tb(III) carboxylate complexes (0.1, 0.25 and 0.5% w/w) was performed. A new complex of the formula Eu2(bpda)3(phen)5 with 1,10-phenanthroline (phen) and biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylate (bpda) ligands was used as a source of the europium(III) ions. The coordination environment of Eu(III) ions contains carboxylate oxygen atoms from the biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylate ligands and nitrogen atoms from 1,10-phenanthroline molecules. Such mode of metal centers binding was also observed in the other ligand mixed complexes of lanthanide ions [21, 22]. For the preparation of hybrid materials containing terbium(III) ions, the complex of Tb(III) with pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylic acid (H2pdc) of the formula Tb2(pdc)3(DMF)3 was used [23]. This polymeric complex contains terbium(III) centers coordinated by seven carboxylate oxygen atoms from the pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate ligands, and one oxygen atom of N,N′-dimethylformamide exhibits intense emission of green light after UV [23].

For the synthesis of hybrid materials, the UV curing technology was applied. This method has many advantages, e.g., high speed, low temperature of the process, low energy utilization, high chemical stability and low costs.

Experimental

Materials

Reagents were used as received without further purification. Bisphenol A glycerolate (1 glycerol/phenol) diacrylate (BPA-Acr), N-vinylpyrrolidone (NVP) and Irgacure 651 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. 1,10-Phenanthroline (for synthesis), pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylic acid (98%) and biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid (98%) were purchased from Merck.

Syntheses of lanthanide(III) complexes

The complex of europium(III) with biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid (H2bpda) and 1,10-phenanthroline (phen) of the general formula Eu2(bpda)3(phen)5 was obtained under the solvothermal conditions. The mixture of EuCl3·6H2O (0.1 mmol) and 1,10-phenanthroline (0.3 mmol) was dissolved in 40 cm3 of the solvent (H2O/CH3OH; 1:1) which was added to the 1.5 mmol of biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid solution. The obtained suspension was stirred and heated at 80 °C for 0.5 h and next transferred to the Teflon-lined steel autoclave and again heated at 100 °C during 5 days. The precipitate was filtered and washed with methanol.

ATR-FTIR (cm−1): ν(CH) 3054–2639; ν(CN) 1679; ν(CC) 1602; νas(COO−) 1583; νs(COO−) 1430; δ(CarH) 1141.

The complex of terbium(III) with pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylic acid (H2pdc) of the formula Tb2(pdc)3(DMF)3 was obtained in the reaction of terbium(III) chloride (1 mmol) with pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylic acid (1.5 mmol) in 20 cm3 of N,N′-dimethylformamide (DMF) by a solvothermal technique. The prepared mixture was sealed in the Teflon-lined autoclave which was heated at the autogenous pressure at 140 °C for 5 days. The precipitate was filtered and washed with DMF [23].

ATR–FTIR (cm−1): ν(CO)DMF 1668; νas(COO−) 1632, 1600; νs(COO−) 1384.

Synthesis of hybrid materials

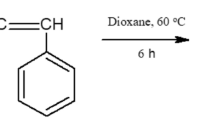

The photopolymerization of bisphenol A glycerolate (1 glycerol/phenol) diacrylate (BPA-Acr) with N-vinylpyrrolidone (NVP) in the presence of UV initiator (Irgacure 651) and luminescent complexes was performed (Table 1, Fig. 1). Firstly, BPA-Acr and NVP (10:3% w/w) were added to the polyethylene containers and mixed. Next, a suitable amount of Eu(III) and Tb(III) carboxylate complexes (0.1; 0.25 and 0.5% w/w) as luminescent components of composites were transferred to the organic mixture. The whole content was gently heated and stirred thoroughly. Finally, the UV initiator (Irgacure 651) (2% w/w) was added.

The liquid compositions containing initiator, monomers and complexes were placed inside the irradiation chamber where they were exposed to UV light by means of two mercury lamps of 500 W each for 0.5 h.

Methods of investigations

The ATR–FTIR (attenuated total reflection–Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy) spectra of Eu2(bpda)3(phen)5, Tb2(pdc)3(DMF)3, BPA-Acr–NVP as well as the prepared materials were recorded over the range of 4000–600 cm−1 on the Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrophotometer equipped with the Smart iTR attachment (diamond crystal).

Thermal analyses of the hybrid materials were carried out by the TG–DTG–DSC methods using the SETSYS 16/18 analyzer (Setaram). The samples (about 7 mg) were heated in alumina crucibles at 30–1000 °C in the dynamic air atmosphere (v = 0.75 dm3 h−1) at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. The TG–FTIR measurements were taken using the Q5000 TA apparatus coupled with Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrophotometer. The samples (about 20 mg) were heated in platinum crucibles up to 700 °C at a heating rate of 20 °C min−1 in flowing nitrogen atmosphere (25 cm3 min−1).

The excitation and emission spectra of the obtained hybrid materials were recorded by means of a PTI QuantaMaster™ spectrofluorometer equipped with a continuous 75-W Xe-arc lamp as the light source at room temperature. The spectra were corrected with respect to the source and detector.

Results and discussion

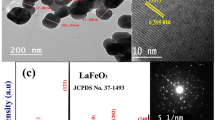

Six novel hybrid materials based on different carboxylate europium(III) and terbium(III) complexes incorporated into the copolymer of bisphenol A glycerolate (1 glycerol/phenol) diacrylate (BPA-Acr) and N-vinylpyrrolidone (NVP) monomers have been synthesized. As the reference material, the copolymer of bisphenol A glycerolate diacrylate with N-vinylpyrrolidone without the addition of complexes was obtained. BPA-Acr is a cross-linking monomer and provides the obtained materials, adequate stiffness and mechanical resistance. In turn, NVP is used as an active diluent and gives the appropriate viscosity of the compositions before cross-linking. The chemical structure of the monomers used in polymerization is shown in Fig. 1. Owing to such method of synthesis, these materials were obtained in the form of a thin layer. In Fig. 2 the fragment of proposed structure of hybrid materials is presented.

The lanthanide complexes of the formulae Eu2(bpda)3(phen)5 Tb2(pdc)3(DMF)3 (where bpda = biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylate; phen = 1,10-phenanthroline; pdc = 3,5-pyridinedicarboxylate; and DMF = N,N′-dimethylformamide) and the polymeric matrix are both coordination polymers due to the bridging character of the polycarboxylate ligands. The embedded complexes interact with copolymer most probably through the π–π stacking interactions between the aromatic rings from ligand and the bisphenol moieties as well as van der Waals forces. It is also possible to assume that the carbonyl groups from the pyrrolidone moieties interact with lanthanide ions forming covalent bonds. Implementation of the carboxylate complexes into the polymeric matrix resulted in luminescence properties originating from europium(III) and terbium(III) ions.

ATR-FTIR characterization

Infrared spectra of the matrix (BPA-Acr–NVP) as well as hybrid materials were recorded by the ATR-FTIR method (Fig. 3). All spectra are dominated by the bands derived from the bisphenol A glycerolate diacrylate compound. In the spectrum of BPA-Acr-co-NVP, the bands derived from the asymmetrical stretching νas(CH2) and symmetrical stretching νs(CH2) vibrations are observed at about 2960 and 2927 cm−1. The intense bands at 1729 and 1667 cm−1 were assigned to the stretching vibrations of the carbonyl groups C=O from the N-vinylpyrrolidone and esters moieties. In the ATR-FTIR spectra of the obtained materials, these bands are only very slightly shifted toward the lower wavenumbers 1727 and 1662 cm−1. This observation can point out the interactions between the incorporated lanthanide complex and the polymeric matrix [24]. In the region 1300–1000 cm−1, the bands’ characteristic of the C–O group of esters is observed. The peaks registered at 1631–1629 and 1607 and 1508 cm−1 were assigned to the stretching vibrations ν(CArCAr) and ν(CN) of aromatic and pyrrolidone rings. The infrared spectra of all obtained materials exhibit several bands at 1286, 1254, 1180, 1107 and 1038 cm−1 which can be ascribed to the stretching vibrations of C–(C=O)–C and C–O–C moieties [25,26,27,28]. The out-of-plane deformation γ(CArH) mode of benzene rings appears at 829 cm−1. The bands derived from ligands of doped complexes are almost invisible in the spectra of the obtained materials due to their low concentrations. Moreover, the bands from the complexes overlapped those from the polymeric matrix.

Thermal analysis of hybrid materials in air

The TG–DTG–DSC and TG–FTIR methods were used for the determination of thermal behavior of polymeric matrix BPA-Acr–NVP and synthesized materials composed of this copolymer as well as the europium(III) and terbium(III) complexes in air and nitrogen atmosphere.

Under the same conditions, thermal decomposition of all investigated materials proceeds a very similar. The addition of lanthanide(III) complexes did not influence significantly the thermal decomposition of polymeric matrix. However, the detailed analysis of the recorded TG–DTG curves of synthesized materials allows to distinguish very slight differences among them (Table 2). The dopants also influence the energetic processes during material heating which is reflected in the shape of DSC curves. The TG–DTG–DSC curves of matrix and hybrid the materials containing the largest amounts of complexes are given in Figs. 4–6.

The matrix is thermally stable in air atmosphere to 86 °C. Further heating leads to a three-stage decomposition resulting in mass losses of about: 13, 59 and 28% observed in the temperature ranges of 87–320, 320–460 and 460–660 °C, respectively. As can be deduced from the shape of DSC curve, heating over 300 °C causes matrix burning of matrix accompanied by a very strong exothermic effect with the maximum at 550 °C. In air the total mass loss for the copolymer is observed at 660 °C.

In the series of hybrid materials doped with 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5% amounts of the Eu2(bpda)3(phen)5 complex, their thermal stability slightly increases (95, 93 and 92 °C). Further heating results also in the three-step decomposition of materials. The detailed analysis of DSC curves allows to notice some differences among them due to the interactions between the dopant complex and the matrix structure. It is worth mentioning that the total mass loss for the europium-doped materials is observed at lower temperatures (636, 634 and 603 °C) compared to the matrix.

In the case of materials based on the Tb2(pdc)3(DMF)3 complex, their thermal stability increases slightly in comparison with the matrix. The material of 0.5% terbium complex concentration exhibits thermal stability to 107 °C, while the remaining materials of 0.25 and 0.1% concentrations of dopants are stable in 105 and 103 °C, respectively. At higher temperature, as it was observed for the materials with the europium complex, also the three-step decomposition takes place. The DSC curves shapes also confirm the presence of the dopants in the materials which affects the pathway of decomposition and burning of the investigated materials. The presence of terbium complex in the materials also decreases the temperature of the total mass loss which is observed for the materials containing 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5% of the complex at 635, 629 and 624 °C, respectively. For all investigated materials, the oxidation process takes place in the range of 450–600 °C.

TG–FTIR analysis in nitrogen atmosphere

Thermal behavior of the matrix and the obtained materials was also investigated in nitrogen atmosphere by the TG–FTIR method. This coupled technique allows to determine thermal stability and pathway of thermal decomposition in inert atmosphere as well as to identify volatile products evolved during heating of materials in inert atmosphere. Due to the great similarity of TG curves of all materials, only those of the materials of the largest content of lanthanide complexes are presented in Fig. 7.

The copolymer exhibits thermal stability in nitrogen up to 124 °C, while the hybrid materials are stable to about 113–111 °C. Only the material of 0.5% content of terbium complex shows higher thermal stability (134 °C) compared to the free matrix. Thermal decomposition of all investigated materials in inert atmosphere proceeds in two distinguishable steps as can be proposed from the shape of TG curves (Fig. 7), the Gramm–Schmidt plots (Fig. 8) and the stacked plot of FTIR spectra of gaseous products of matrix thermal decomposition (Fig. 9). The first mass loss of about 10–13% takes place in the range of 111–340 °C. As can be deduced from the FTIR spectra of gaseous products of thermal decomposition, this stage is probably connected with the release of pyrrolidone molecules. The single spectrum recorded at 260 °C during the copolymer decomposition (Figs. 10, 11) fits well with the reference spectrum from the library [29]. The bands with the maxima at 2983 and 2888 cm−1 assigned to the stretching vibrations of CH groups are observed. The strong band at 1739 cm−1 was assigned to the amide I band predominantly associated with the carbonyl group. The bands at 1381 and 1269 cm−1 are due to the bending vibrations of CH2 and NH groups from the pyrrolidone ring [26]. The other molecule released in the first step of decomposition is methyl acetate due to the presence of the bands in the range of 3050–2960 cm−1 and those at about 1460 and 1380 cm−1 from the stretching and deformation vibrations of methyl groups [29]. The other strong bands at about 1248 and 846 cm−1 can be ascribed to the stretching vibrations of C–O and CC groups [27, 28]. Further decomposition takes place in the range of 340–530 °C where at first carbon dioxide molecules are evolved. The single infrared spectrum recorded at 350 °C shows characteristic sharp bands with the maxima at 2390 and 2340 cm−1 and those at 669 cm−1 from the stretching and deformation vibrations of CO2 (Fig. 10). At the same time, a very indicative doublet of bands at 2150 and 2090 cm−1 is present due to carbon oxide release. Additionally, medium intense bands from the evolved water molecules appear in the ranges of 3900–3500 cm−1 and 1900–1400 cm−1 [30,31,32]. Simultaneously several bands are observed in the ranges of 3100–2900 and 1900–1150 cm−1 due to bisphenol A molecules which give the bands at: 3649 and 3030, and 2969 cm−1 assigned to the stretching vibrations of OH groups from phenol and CH groups from the aromatic rings and aliphatic systems of bisphenol A [25]. The bands present at 1607 and 1507 cm−1 are characteristic of the stretching vibrations CArCAr of aromatic rings. The bands at 1257, 1175, 827 and 746 cm−1 are due to stretching and bending vibrations of different HCH, CCH and COH moieties. Methane molecules are evolved along with bisphenol A which gives the very diagnostic band at 3015 cm−1.

Thermal decomposition of N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone units is responsible for the presence of characteristic bands for ammonia (960 cm−1), amides (1660 cm−1) as well as aldehydes and ketones (1700–1720 cm−1) and CO2 [33,34,35,36]. The proposed scheme of thermal decomposition of polymeric matrix is presented in Fig. 12.

Thermal decomposition of all investigated materials occurs with the release of similar decomposition volatile products. Only the shapes of Gramm–Schmidt plots (Fig. 8) which show intensity of evolved gases during heating allow to notice some differences in the mechanism of thermal decomposition of investigated materials.

Luminescent properties

Synthesized hybrids based on polymer material were investigated by the photoluminescence methods. Due to the well-known europium and terbium luminescence in the visible spectral region, the room temperature excitation and emission spectra were collected. The excitation spectrum of BPA-Acr–NVP-0.5Eu measured by monitoring the emission of Eu(III) ions at 616 nm is shown in Fig. 13. It exhibits a broadband in the region of 300–350 nm which originates from the ligand and surrounding matrix and can be attributed to intraligand charge change and the ligand–to–metal charge transfer [17]. The other bands in the spectrum located at 396, 417, 466, 527 and 537 nm are characteristic for Eu(III) ions and correspond to the 7F0–5L6, 7F1–5D3, 7F0–5D2, 7F0–5D1 and 7F1–5D1 transitions, respectively [37]. The investigation of photoluminescence spectra recorded using direct Eu(III) excitation at 396 nm in comparison with indirect excitation in the ligand band region (Fig. 14) clearly shows that sensitization of europium(III) emission occurs mainly through energy transfer from the ligand states of the complex embedded in the BPA-Acr–NVP polymer matrix. This process is known as the antenna effect. Upon excitation at 329 nm, all investigated europium complex doped materials display strong and narrow emission bands corresponding to characteristic transitions of trivalent europium ion: 5D0–7F0 (581 nm), 5D0–7F1 (594 nm), 5D0–7F2 (616–621 nm), 5D0–7F3 (653 nm), 5D0–7F4 (694–701 nm) (Fig. 15). The majority of the transitions observed in the photoluminescence spectra are induced electric dipole transitions. The most intense of them is the hypersensitive transition. Its intensity is much more influenced by the local symmetry of the Eu3+ ion and the nature of the ligands than the intensities of the other electric dipole transitions. It is also responsible for the red emission of the complex. The observed splitting of the band suggests D3 symmetry of the complex [3]. The 5D0–7F1 transition at 594 nm has a magnetic dipole character and is fairly insensitive to the metal environment.

Photoluminescence characterization of hybrid materials containing Tb is presented in Fig. 16. It is not as accurate as in the case of Eu due to the low intensity of the terbium bands. Nevertheless, the main emission bands at 488, 544, 582, 589, 614 and 621 nm due to 5D4 → 7F6,5,4,3 transitions are observed. The most intense and sharpest band is located at 544 nm and arises from 5D4 → 7F5 magnetic dipole transition generating the green luminescence of the complex [37, 38].

Conclusions

The efficient synthesis of hybrid transparent materials composed of polymeric matrix and special dopants—carboxylate europium(III) and terbium(III) complexes in the form of thin layers was presented. The lanthanide dopants did not drastically change the thermal stability of polymeric matrix. All hybrids decompose in three stages in air atmosphere, while in nitrogen they degraded in two steps. Additionally, these materials exhibit higher thermal stability in the inert atmosphere. TG–FTIR analysis allowed to distinguish the following volatile products of decomposition: pyrrolidone, methyl acetate, carbon oxides, water, bisphenol A and methane. Implementation of the lanthanide complexes into the polymeric matrix resulted in luminescence properties of obtained hybrids. Materials doped with europium(III) complex emit characteristic red luminescence, while those containing terbium(III) ions emit green one after UV irradiation. The strong emission from lanthanide ions after indirect excitation in the ligand spectral region is clearly observed due to antenna effect. It is worth to notice that surrounding polymer matrix does not disturb photoluminescence properties of Eu(III) and Tb(III) complexes. These kinds of transparent polymeric hybrid materials can be expected to have potential applications in industrial fields for example as UV-protective coatings.

References

Oban R, Matsukawa K, Matsumoto A. Heat resistant and transparent organic–inorganic hybrid materials composed of N-allylmaleimide copolymer and random-type SH-modified silsesquioxane. J Polym Sci Part A: Polym Chem. 2018;56:2294–302.

Unterlass MM. Green synthesis of inorganic–organic hybrid materials: state of the art and future perspectives. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2016;8:1135–56.

Binnemans K. Lanthanide-based luminescent hybrid materials. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4283–374.

Podkościelna B, Sobiesiak M. Synthesis and characterization of organic–inorganic hybrid microspheres. Adsorption. 2016;22:631–8.

Bolbukh Y, Podkościelna B, Lipke A, Bartnicki A, Gawdzik B, Tertykh V. Immobilization of polymeric luminophor on nanoparticles surface. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2016;11:206–15.

Kango S, Kalia S, Celli A, Njuguna J, Habibi Y, Kumar R. Surface modification of inorganic nanoparticles for development of organic–inorganic nanocomposites—a review. Prog Polym Sci. 2013;38:1232–61.

Jancar J, Douglas JF, Starr FW, Kumar SK, Cassagnau P, Lesser AJ, Sternstein SS, Buehler MJ. Current issues in research on structure–property relationships in polymer nanocomposites. Polymer. 2010;51:3321–43.

Florjańczyk Z, Dębowski M, Chwojnowska E, Łokaj K, Ostrowska J. Polimery syntetyczne i naturalne w nowoczesnych materiałach polimerowych. Polimery. 2009;54:611–25.

Chrissafis K, Bikiaris D. Can nanoparticles really enhance thermal stability of polymers? Part I: an overview on thermal decomposition of addition polymers. Thermochim Acta. 2011;523:1–24.

Chujo Y. Organic–inorganic nano-hybrid materials KONA. 2007;25:255–60.

Kickelbick G. Introduction to hybrid materials. In: Kickelbick G, editor. Hybrid materials: synthesis, characterization and applications. New York: Wiley; 2007. p. 1–48.

Carlos LD, Ferreira RAS, de Zea Bermudez V, Julian-López B, Escribano P. Progress on lanthanide–based organic–inorganic hybrid phosphors. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:536–49.

Wang J, Dou W, Kirillov AM, Liu W, Xu C, Fang R, Yang L. Hybrid materials based on novel 2D lanthanide coordination polymers covalently bonded to amine-modified SBA-15 and MCM-41: assembly, characterization, structural features, thermal and luminescence properties. Dalton Trans. 2016;46:18610–21.

Aguiar FP, Costa IF, Espínola JGP, Faustino WM, Moura JL, Brito HF, Paolini TB, Felinto MCFC, Teotonio EES. Luminescent hybrid materials functionalized with lanthanide ethylenodiaminotetraacetate complexes containing β-diketonate as antenna ligands. J Lumin. 2016;170:538–46.

Yang D, Wang Y, Wang Y, Li Z, Li H. Luminescence enhancement after adding organic salts to nanohybrid under aqueous condition. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:2097–103.

Łyszczek R, Gil M, Głuchowska H, Podkościelna B, Lipke A, Mergo P. Hybrid materials based on PEGDMA matrix and europium(III) carboxylates-thermal and luminescent investigations. Eur Polym J. 2018;106:318–28.

Ma X, Li X, Cha Y-E, Jin LP. Highly thermostable one-dimensional lanthanide(III) coordination polymers constructed from benzimidazole-5,6-dicarboxylic acid and 1,10-phenanthroline: synthesis, structure, and tunable white-light emission. Cryst Growth Des. 2012;12:52227–5232.

Tsaryuk V, Zhuravlev K, Zolin V, Gawryszewska P, Legendziewicz J, Kudryashova V, Pekareva I. Regulation of excitation and luminescence efficiencies of europium and terbium benzoates and 8-oxyquinolinates by modification of ligands. J Photochem Photobiol A. 2006;177:314–23.

Podkościelna B. New photoluminescent copolymers of naphthalene-2,7-diol dimethacrylate and N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone: synthesis, characterisation and properties. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2014;116:785–93.

Podkościelna B, Lipke A, Majdan M, Gawdzik B, Bartnicki A. Thermal and photoluminescence analysis of a methacrylic diester derivative of naphthalene-2,7-diol. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;126(1):161.

He H, Yuan D, Ma H, Sun D, Zhang G, Zhou H-C. Control over interpenetration in lanthanide-organic frameworks: synthetic strategy and gas-adsorption properties. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:7605–7.

Huang X, Wang Q, Yan X, Xu J, Liu W, Wang Q, Tang Y. Encapsulating a ternary europium complex in a silica/polymer hybrid matrix for high performance luminescence application. J Phys Chem. 2011;C115:2332–40.

Łyszczek R. Synthesis, structure, thermal and luminescent behaviors of lanthanide—pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate frameworks series. Thermochim Acta. 2010;509:120–7.

Srinivas Ch, Sanjeeva Rao B, Kalahasti S. Study on poly acrylic acid–silver polymer composites. Indian J Sci Res. 2017;13(1):212–7.

Ullah R, Ahmad I, Zheng Y. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of “bisphenol A”. J Spectrosc 2016;2016:1–5.

Pandey P, Samanta AK, Bandyopadhyay B, Chakraborty T. Infrared spectroscopy of 2-pyrrolidinone and its hydrogen bonded dimers in a cold (8 K) inert gas matrix. Vib Spectrosc. 2011;55:126–31.

Holly S, Sohar P. Absorption spectra in the infrared region. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado; 1975. p. 47–135.

Silverstein RM, Webster FX. Spectrometric identifications of organic compounds. New York: Wiley; 1998. p. 45–109.

Thermo Scientific™ Inc. OMNIC™ specta software. 2009.

Łyszczek R. Thermal investigation and infrared evolved gas analysis of light lanthanide(III) complexes with pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylic acid. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2009;86:239–44.

Łyszczek R, Łyszczek R, Bartyzel A, Głuchowska H, Mazur L, Sztanke M, Sztanke K. Thermal investigations of biologically important fused azaisocytosine-containing congeners and the crystal structure of one representative. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2018;135:141–51.

Yang Z, Gu Z, Yang X, Zhang Z, Wang X, Chen X, Yang L. The mechanism study on the cooperative flame resistance effect between HMP and NP in ABS by TG–FTIR. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;129:303–14.

Xu L, Che L, Zheng J, Huang G, Wu X, Chen P, Zhang L, Hu Q. Synthesis and thermal degradation property study of N-vinylpyrrolidone and acrylamide copolymer. RSC Adv. 2014;4:33269–78.

Sobiesiak M, Podkościelna B, Sevastyanova O. Thermal degradation behavior of lignin-modified porous styrene–divinylbenzene and styrene–bisphenol A glycerolate diacrylate copolymer microspheres. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2017;123:364–75.

Sidi-Yacoub B, Oudghiri F, Belkadi M, Rodriguez-Barroso R. Characterization of lignocellulosic components in exhausted sugar beet pulp waste by TG/FTIR analysis. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08179-8.

Yıldız Z, Ceylan S. Pyrolysis of tobacco factory waste biomass TG–FTIR analysis, kinetic study and bio-oil characterization. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2019;136:783–94.

Richardson FS. Terbium(III) and europium(III) ions as luminescent probes and stains for biomolecular systems. Chem Rev. 1982;82:541–52.

Bünzli JCG. On the design of highly luminescent lanthanide complexes. Coord Chem Rev. 2015;293-294:19–47.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Łyszczek, R., Podkościelna, B., Lipke, A. et al. Synthesis and thermal characterization of luminescent hybrid composites based on bisphenol A diacrylate and NVP. J Therm Anal Calorim 138, 4463–4473 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08914-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08914-1