Abstract

The gelcasting method was used to form gastight Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 samples proposed for use as proton-conducting electrolytes in solid oxide fuel cells. Methylcellulose was used as an environmentally friendly shaping agent for Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 powder in an ethanol solution. Samples of Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 were also prepared from the same powder via traditional isostatic pressing, as a reference for cast samples, and sintered in the same conditions. Comparative studies of the physicochemical properties of Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 electrolytes, formed by means of these two methods and then sintered at 1550 °C for 2.5 h, were presented and discussed. Using the X-ray diffraction method, only the pure orthorhombic phase of BaCe0.9Y0.1O3 was detected in the Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 powder, as well as in the Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 sintered pellets formed via both gelcasting (A) and isostatic pressing (B). Thermal effects occurring during heating of methylcellulose, as well as ceramic Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 powder, dried cast samples obtained from the prepared slurry, and sintered Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 samples, were examined by differential scanning calorimetry, differential thermal analysis, thermogravimetric analysis, and evolved gas analysis of volatile products using a quadrupole mass spectrometer. The measurements were performed within the temperature range of 20–1200 °C in air. Based on dilatometric tests, it was found that the Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 cast samples exhibited slightly higher degree of sinterability than the 5CBCY samples obtained by isostatic pressing. In comparison with pressed pellets, higher values of total electrical conductivity in air or in a gas mixture of 5% H2 in Ar were also attained for Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 cast samples. The Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 samples were used to construct oxygen–hydrogen electrolytes for solid oxide fuel cells. The results of the electrochemical performance of solid oxide fuel cells with Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 electrolytes were comparable to the data in the literature on BaCe0.9Y0.1O3 electrolytes. An electrochemical study of a Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3−δ|Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 interface was also performed. Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3−δ appears to be a suitable cathode material for a Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 electrolyte.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ceramic proton conductors appear to be valuable components in the development of cost-effective SOFCs operating within an intermediate-temperature (IT) range of 500–700 °C and a low-temperature (LT) range of 350–600 °C. Protons are characterised by a higher level of mobility than oxygen ions because of their much smaller size. The diffusion of protons is also much less temperature-dependent than that of oxygen ions. Therefore, it is potentially easier to obtain greater conductivity for proton conductors than for oxygen ion conductors at lower temperatures [1, 2]. One of the main groups of ceramic proton conductors with perovskite structures (ABO3) currently under investigation comprises cerates [3]. Although BaCe1−xYxO3 (0 < x < 0.2) ceramic proton conductors have been chiefly proposed for application in IT-SOFCs, they possesses certain disadvantages, namely limited stability in CO2 gas atmospheres and only moderately favourable mechanical properties [4, 5].

Compared to the starting composition BaCe0.9Y0.1O3, the partial substitution of calcium for barium, resulting in a (Ba1−xCax)(Ce0.9Y0.1)O3 solid solution, where 0 < x < 0.1, led to an improvement in chemical stability in atmospheres including CO2 gas. Thus, the modified Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 material appears to be a more suitable ceramic proton-conducting electrolyte for solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs), solid oxide electrolyser cells (SOECs), or probes for monitoring hydrogen in gas atmospheres or liquid metals [6, 7].

The commercial application of electrochemical devices based on Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 (5CBCY) requires the elaboration of gastight, complexly shaped ceramic parts from electrolytic materials. Tape casting is a low-cost process particularly well suited to the fabrication of thin (10–1000 µm) flat components for solid oxide fuel cells, enabling the production of a wide variety of controlled morphologies, from highly porous to fully dense microstructures such as electrodes and electrolytes. This technique is usually applied to the manufacture of components for planar elements for electrochemical devices such as SOFCs and SOECs. The physicochemical and electrochemical properties of 5CBCY ceramic tape obtained from a non-aqueous system were presented in our previous paper [8].

Nowadays, the gelcasting method of forming ceramic materials appears to be very useful in the development of intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cell (IT-SOFC) technology, along with variously shaped ceramic electrolytes for the construction of the desired electrochemical devices [9,10,11]. This method has been applied in order to obtain thin electrolytic films or variously shaped ceramic tubes involving yttria-stabilised zirconia (YSZ), samaria-doped ceria (SDC), or gadolina-doped ceria (GDC) [12, 13]. It has also been used in the fabrication of ceramic proton-conducting materials such as BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.2O3−δ [14].

In most prepared ceramic electrolytes, the aqueous gelcasting technique uses monofunctional acrylamide CH2=CHCONH2 and difunctional N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (CH2=CHCONH2)2CH2 as organic reactive monomers. The main disadvantage of this gelling system is that acrylamide is a neurotoxin [15]. Therefore, many new gel formers, especially those consisting of low-toxicity monomers or environmentally friendly biopolymers, are being studied extensively [16, 17].

Methylcellulose, a water-soluble organic compound widely used for extrusion and injection moulding, has been shown to undergo thermally induced gelation at temperatures within the range 70–80 °C [18, 19]. It is also known to form a sufficiently strong gel capable of converting a ceramic slurry to consolidated shapes via thermal gelation at 70–80 °C, even when the concentration of gelling matter is as low as below 0.5 mass%, as was shown in other papers concerning dense alumina and highly porous hydroxyapatite [20, 21]. With respect to Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 ceramics, the concentration of the organic gelling binder should be kept low, in order to minimise the carbon residue content following the sintering process, which may have an effect on the electrical properties of Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3. It should be noted that commonly used gelling agents, such as monomers with cross-linkers, serve as strong hydrogels when their concentration in ceramic slurry is much higher than methylcellulose, usually about 5 mass% [22].

The aim of this paper is to examine the potential for forming ceramic materials from modified calcium–barium–yttrium-doped cerate with the formula Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 (5CBCY) via the gelcasting method, using methylcellulose as an environmental networking agent. Thus, the current paper investigates the physicochemical properties of 5CBCY sintered samples, as well as electrochemical cells constructed using these samples.

Experimental

Preparation of Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 (5CBCY) powder

Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 (5CBCY) monophase powder was synthesised by means of a solid-state reaction. The starting reagents were barium carbonate and calcium carbonate (Avantor Performance Material Poland S.A, p.a.), yttrium(III) oxide (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.99%), and cerium oxide (Acros Organics, 99.9%). Stoichiometric amounts corresponding to the Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 formula were homogenised and milled in a planetary ball mill (Retsch PM 100), in dry ethanol with grinding media made from yttria-stabilised zirconia with a diameter of 5 mm. According to previous experiments, the rotational speed of the mill was established at 300 rpm. The powders were homogenised for 24 h in 20-min cycles consisting of 5-min milling stages and 15-min cooling stages. The total homogenisation time of the powders was 6 h. The pure monophasic 5CBCY was synthesised at 1200 °C. The 5CBCY powder was ground in dry ethanol with grinding media made from yttria-stabilised zirconia, 5 mm in diameter. The total milling time of monophasic 5CBCY powder samples was 8 h. The BET surface area was ca. 5 g m−2; the average particle size (D50) was 0.5 µm. The procedure was previously described in paper [7, 8].

Preparation of slurry for the 5CBCY gelcasting process

Methylcellulose (Sigma-Aldrich, Poznań, Poland, M.W. ~ 90.000) was used in this paper as a gelling agent. Methylcellulose solution (2 mass%) was prepared by dissolving 1 g of methylcellulose in 49 g of water. The solution was set aside for 24 h for defoaming. Fifteen grams of 5CBCY powder were mixed with 2.5 g of dry ethanol. Subsequently, 5 g of methylcellulose solution and 0.15 g of a dispersing agent (Dolapix PC75) were introduced into the powder suspension, which was vigorously mixed for 10 min and degassed under vacuum (− 0.85 bar, 5 min). Next, the slip was poured into aluminium or polythene moulds and heated to 80 °C in an oven to initiate gelling. During the gelling process, the samples were covered with a Petri dish. The final stage of drying was carried out overnight in an oven at 80 °C. Dried samples were sintered at 1550 °C for 2.5 h on platinum foil. During the sintering process, the samples were covered with a platinum crucible. The samples formed via the gelcasting technique are designated as (A) throughout this paper. Reference pellets of 5CBCY with similar dimensions were also formed from the same powder via the isostatic pressing method whereby the samples were first pressed in a mould measuring 28 mm under 0.5 MPa. At this stage, the samples were only mechanically formed, stable shapes. In the next stage, the pressed samples were placed in plastic foil, outgassed, and pressed under 250 MPa. A National Forge isostatic cold press (Germany) was used. These samples are designated as (B) throughout this paper. The samples obtained by method B were sintered and investigated in analogous conditions. Thus, it was possible to make a direct comparison of the physicochemical properties of 5CBCY samples formed via different methods.

Analytical methods of evaluation of the physicochemical properties of 5CBCY samples

The rheological behaviour of the suspensions involving 5CBCY powder was determined using rotary a rheometer (Rheotest R.V.2, Rheotest Messgeräte Medingen, Germany) fitted with double concentric cylinder geometry. All rheological measurements were conducted at shear rates from 5 to 1310 s−1 at room temperature.

XRD measurements, performed using a PANalytical Empyrean system with monochromatic CuKα radiation, were used to determine the phase composition of 5CBCY powder as well as of sintered 5CBCY samples obtained by method (A) or (B). The lattice parameters of the 5CBCY samples were determined using the Rietveld method. Thermal analysis (DTA/TG; DSC/TG, STA 449 F3 Jupiter thermal analyser, Netzsch, Germany) was used to determine thermal effects occurring during the heating of starting reagents such as methylcellulose (MC) as well as of 5CBCY ceramic powder, dried cast samples obtained from prepared slurry, and 5CBCY sintered samples. The measurements were performed within the temperature range of 20–1200 °C in air. The applied rate of increase in temperature over time (ramp) was 10 °C min−1. Some investigations were also performed on a thermoanalyser (TA Instruments SDT 2960), which enabled simultaneous detection of mass changes and heat effects occurring during the heating of the samples. Gaseous products of reactions were analysed using a quadruple mass spectrometer.

Dilatometry was used to identify variations in the dimensions of 5CBCY samples heated within a temperature range of 25–1200 °C. A Netzsch DIL 402 (Germany) apparatus was used. The density of the 5CBCY samples was determined using Archimedes’ method. Scanning electron microscopy (Nova NanoSEM 200 FEI, Netherlands) coupled with an EDS system (EDAX, Netherlands) was used to examine the microstructure of the 5CBCY sintered samples (A) and (B).

Electrical conductivity measurements

Electrical conductivity measurements of the sintered 5CBCY gelcast samples were performed using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The measurements were performed in air and in an H2–Ar gas atmosphere within the temperature range 400–750 °C, using a Solartron SI 1255B Frequency Response Analyser equipped with a 1287 Electrochemical Interface; AC voltage with an amplitude of 10 mV was applied within a frequency range of 1 Hz–1 MHz.

Electrochemical tests of 5CBCY-electrolyte-supported solid oxide button fuel cells

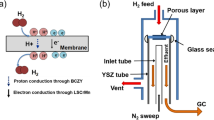

The following hydrogen–oxygen solid oxide fuel cell was investigated:

Sintered 5CBCY electrolytes were cropped to the shape of discs with diameters of 20 mm. The top and bottom surfaces were ground in order to reduce the thickness of each electrolyte to less than 1 mm. Porous platinum electrodes (with active surfaces of approximately 1.3 cm2) were applied in the initial electrochemical tests described in this paper. The electrodes were screen-printed from commercial Pt (Heraus, Germany). Electrolytes with Pt electrodes were heated at 1000 °C for 1 h to obtain porous forms for both electrodes and to bind the platinum layers firmly to the electrolyte. Fuel cell performance was tested within the temperature range 550–700 °C. The anode was fed with humidified hydrogen; humidified air was supplied to the cathode. The electrochemical set-up for the investigation of electrolyte-supported solid oxide button fuel cells was described in the previous paper [23].

Electrochemical investigations of the cathode–electrolyte interface in a BSCF|5CBCY system

Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3−δ (BSCF) (Treibacher, Austria) powder was mixed with α-terpineol (Sigma-Aldrich) to obtain a paste. The electrochemical cell used for the electrode tests in air was a three-electrode cell, prepared by means of slurry-coating the prepared paste with the use of a shaped mask and a blade on both sides of the electrolyte disc. BSCF working and counter electrodes with diameters of 6 mm were placed on opposite sides of the 5CBCY electrolyte; a BSCF reference electrode in the shape of a ring with an inner diameter of 12 mm and an outer diameter of 14 mm was placed on the same side as the working electrode, as shown in Fig. 1 in [24]. Thus prepared, the electrodes were dried at 90 °C for 12 h and sintered at 1100 °C for 2 h at heating and cooling rates of 2.0 and 3.0 °C min−1, respectively. Platinum nets were used as current collectors on all electrodes and connected to an Autolab PGSTAT302 N potentiostat with a frequency response analyser. Impedance measurements were performed at open-circuit potential at 600 °C in oxygen and in mixtures of argon with oxygen with values of \(P_{{{\text{O}}_{2} }}\)P−1 of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 and a flow rate of 100 mL min−1. Spectra were recorded with a density of 8 points per decade, with 10 mV sinusoidal perturbation amplitude within a range of 0.1 Hz–100 kHz. The program MINUIT [25], obtained from CERN, based on a complex nonlinear regression least-squares procedure, was used to fit an equation describing the assumed equivalent electrical circuit (EEC) to the measured data. The data treatment procedure is described in detail elsewhere [26].

Results and discussion

Figure 1 presents the viscosity measurements with shear rates of 35 vol% ceramic slurries without methylcellulose (MC) and with an addition of 0.6 mass% of MC on the basis of solids. The plot for ceramic slurry with the addition of methylcellulose clearly indicated an increase in viscosity. This effect was expected, since the methylcellulose solution was characterised by generally higher viscosity than pure solvent. However, the viscosity within a shear rate range of 10–100 s−1 was less than 1.5 Pa, i.e. convenient for gelcasting slips. All the slips prepared in this work revealed shear thinning. This behaviour is characterised by a decrease in viscosity along with increasing shear rate and is typically found in the dispersion of ceramic suspensions containing a large percentage of solids.

Figure 2a–d presents the following 5CBCY samples: (a) those resulting from the gelcasting process, (b) cast samples after being dried in the laboratory dryer, (c) samples sintered at 1550 °C for 2.5 h, and (d) 5CBCY-electrolyte-supported solid oxide fuel cells with covered Pt porous electrodes. Rounded 5CBCY sintered samples with diameters of ~ 20 mm were used for electrochemical investigations. This size is typical of ceramic electrolytes for solid oxide button fuel cells, which are often used in laboratory tests prior to being scaled to larger dimensions [27].

Figure 3 presents the X-ray diffraction pattern recorded for sintered 5CBCY samples formed by means of the gelcasting (A) and isostatic pressing (B) methods. Data for the 5CBCY starting powder (P) have been added. For all samples, the XRD patterns reflect the references symmetry of the orthorhombic BaCe0.9Y0.1O3 phase.

Table 1 presents the cell parameters and cell volume determined for the Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 samples formed via the gelcasting method (A) or via cold isostatically pressing (B). Similar cell parameters and calculated cell volumes were obtained for both samples. These data are in close agreement with the results presented in our previous paper [7].

Thermal analysis (DSC/TG) was performed to determine the thermal effects that might occur during the heating of 5CBCY samples. Data on variations in 5CBCY cast samples during heating are necessary to establish optimal sintering conditions in order to obtain gastight samples. This crucial processing operation during the densification of 5CBCY samples involves release of the organic medium from the ceramic part, reduction in porosity, and acquisition of gastight samples without cracks or certain defects.

Figure 4a, b presents the DSC/TG curves recorded for the main starting reagents used for preparing slurry: (a) methylcellulose or (b) 5CBCY starting ceramic powder. The heating of methylcellulose to ~ 300 °C caused a decrease in mass due to the start of the process of methylcellulose pyrolysis, which corresponds to a small exothermic peak at 297.4 °C on the DSC curve. The thermal decomposition of methylcellulose generally occurs through pyrolysis reactions such as primary thermal decomposition, followed by secondary decomposition reactions. An increase in temperature caused the presence of the second exothermic peak at ~ 365 °C on the DSC curve, which also corresponds to the processes of char formation. Within the temperature range 500–600 °C, total combustion of organic matter was usually observed [28, 29]. On the DSC curve, a strong exothermic peak at ~ 472 °C corresponds to the combustion of organic matter. Based on TG analysis, the total mass decomposition equalled ~ 99.97% at 500 °C An analysis of mass variation for methylcellulose was also conducted following the heating of samples at temperatures of 300–500 °C in air for 30 min at each temperature. Mass losses of the original sample at 300 °C were estimated at 7%, but as the temperature rose to 400 °C and then to 500 °C, total mass losses of, respectively, ca. 99.5% and ca. 99.8% were observed. These results were in close agreement with the data which had been recorded for the TG curve.

In the case of DSC/TG and EGA (Fig. 4b) recorded for the pure monophase 5CBCY powder, continued heating of the sample within the temperature range 20–1200 °C did not lead to any significant thermal effects. Only a small endothermic peak was observed at ca. 970 °C. It can be attributed to decomposition of residual BaCO3. The appearance of the CO2 current peak at this temperature on the EGA curve confirmed these observations. The total mass losses were estimated at ca. 4.3% compared to the initial sample. Figure 4c presents DSC/TG curves recorded for dried cast 5CBCY samples within the temperature range 25–1100 °C. Generally during ceramic processing, the organic medium is removed by thermolysis in an oxidising atmosphere. The first visible thermal effect on the DSC curve is a small endothermic peak at ~ 119 °C. This peak may correspond to the evaporation of water. An increase in temperature caused the presence of two small exothermic peaks at ~ 272.9 and ~ 290.7 °C on the DSC curve. These effects correspond to the onset of decomposition of organic matter in the 5CBCY sample. The observed thermal effects (at 812 °C, 1059 °C, and 1082 °C) may also be connected with the decomposition of CaCO3 or BaCO3, as possible products of the BaCe0.9Y0.1O3 and CO2 phases. The increase in the H2O or CO2 current at respective temperatures on the EGA curve confirmed these observations. It is generally known that BaCe0.9Y0.1O3 is characterised by limited stability in the presence of CO2 [30,31,32]. Previous studies found that Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 was characterised by improved chemical resistance compared to BaCe0.9Y0.1O3, but the problem of instability was not completely solved. The decomposition reaction (2) was described in [7].

The total pressure of CO2 in a gas atmosphere also has an impact on the initial temperature of BaCO3 decomposition. The total mass losses were estimated at ~ 10% within the investigated temperature range.

The performed DSC/TG analysis (Fig. 4a–c) helped to elaborate the profile of sintering 5CBCY samples formed via the gelcasting method (A), which can be seen in Fig. 5.

For methylcellulose (MC) and Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 dried samples, the thermal effects corresponding to decomposition and initial burning of organic parts (MC or a mixture of solvent MC, ethanol, and Dolapix) occurred at the first stage of heating to 450 °C, and losses of mass on the TG curve were visible; accordingly, an increase in heating temperature of 1.5 °C min−1 and heating for 120 min enabled the removal of gases as products of organic decomposition. Slow heating of samples from 450 to 1550 °C enabled the evaporation of all gases, which may directly correspond to the combustion of organic. It is important to remove carbon originating from an organic medium from sintered samples, because the residual carbon can affect the total electrical resistance as well as increasing electronic conduction, which is undesirable for the application of 5CBCY as ceramic ionic conduction membranes. Another reason was to obtain a uniform microstructure, which enabled the acquisition of high values of electrical conductivity as well as tolerance in terms of the dimension and quality of sintered discs. Cooling to 1000 °C was also accomplished slowly.

DTA/TG curve recorded for the crushed 5CBCY crushed sample (A), sintered according to the profile in Fig. 5, is presented in Fig. 6. The aimed aim of this investigation was to determine the possible potential mass losses, which can be connected with removing the removal of CO2 as a product of the combustion of residual carbon. Based upon the TG analysis, the estimated mass losses were amounted to ca. 0.3%, so it can concluded that residual carbon was removed in the applied sintering conditions. The similar level of mass losses on TG curve was observed in case of BaCe0.9Y0.1O3 or Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 samples formed by method (B). Another reason for mass losses at this temperature might also be the decrease in H2O content as well as increase in nonstoichiometry in anion/oxygen sublattice ABO3−δ [33, 34].

DTA/TG curve recorded for 5CBCY crushed sample (A) following the sintering process according to the profile from Fig. 5

Figure 7 presents the densification behaviour of a 5CBCY ceramic sample formed via method (A) or (B) and heated at a constant rate of 5 °C min−1 within a temperature range of 25–1200 °C. Shrinkage of 5CBCY sample A began at about 200 °C, with gradual densification of cast samples along with increased temperatures. At 1250 °C, the linear shrinkage reached values close to 8%. In the case of 5CBCY sample B, the level of linear shrinkage Δl reached a value close to 5% at the same temperature. In the case of the 5CBCY cast and sintered sample at 1550 °C for 2.5 h, linear shrinkage reached ~ 18%. The relative density of a 5CBCY sample formed by (A) or (B) at a temperature of 1550 °C reached ~ 94–95% of theoretical density.

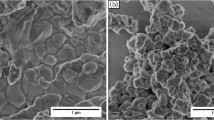

The results of SEM observations of a cross section of a sintered 5CBCY sample formed via method (A) are presented in Fig. 8a. A uniform microstructure with grain sizes of 5–10 μm was visible. Only negligible porosity was noted in the observed cross section of the 5CBCY electrolyte. For comparison, the SEM image recorded for 5CBCY sample (B) formed via isostatic pressing and sintered at 1550 °C for 2 h is also presented in Fig. 8b. As can be seen, the two samples are characterised by similar levels of densification. A uniform microstructure and grain sizes of 6–8 µm were observed.

This result indicates that applied gelcasting with an environmentally friendly system appears to be a promising technique for forming ceramic electrolytes based on modified Ca0.05Ba0.95Ce0.9Y0.1O3.

The electrical and electrochemical properties of 5CBCY samples are crucial for their application as electrolytes in electrochemical devices. The temperature dependences of total conductivity, measured via the four-probe DC method in dry air, for 5CBCY formed via method (A) or (B) are presented in Arrhenius plots in Fig. 9. In a direct comparison of total electrical conductivity dependence in air recorded for 5CBCY samples A and B, it was found that the sample formed via gelcasting exhibited slightly higher values of electrical conductivity than that formed via the isostatic pressing method. It was also found that energy activation Ea for total electrical conductivity determined for 5CBCY sample (A) reached lower values than for that obtained via method (B). This finding can be attributed to the superior homogenisation of powders in the casted 5CBCY samples. The dependence of total electrical conductivity (σ) versus temperature (Fig. 10) was also recorded for 5CBCY samples formed via methods A or B in a 5 vol% H2–Ar wet gas mixture. Moreover, higher values of total electrical conductivity within the investigated temperature range were obtained for the 5CBCY sample formed via the gelcasting technique than for that formed via method B. Also, lower energy activation values (Ea = 0.49 eV) were determined for 5CBCY sample A than for sample B (Ea = 0.59 eV).

The data for total electrical conductivity (σ) obtained in this study for Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 samples formed via methods (A) or (B) were compared with the data in the relevant literature for BaCe0.9Y0.1O3-based samples. For all samples, the data, collected in Table 2, refer to measurements in air.

Analysis of total electrical conductivity values (σ) for 5CBCY samples as well as BCY samples in air within the temperature range 600–700 °C determined that the former exhibited essentially the same level of total electrical conductivity as the latter. This finding is dependent on the microstructure of the ceramic materials. The conditions applied to powder preparation and the formation of shapes and sintering of ceramic parts exert a considerable impact on the creation of their microstructure under the applied thermal treatment conditions. The humidity level of the air during electrical conductivity (σ) measurements also has a great impact on the slight differences visible in the electrical conductivity values presented in Table 2 [35,36,37].

Figure 11 presents the voltage (U)–current (I) dependence recorded for 5CBCY-electrolyte-supported solid oxide fuel cells. Initially, as can be seen, the recorded OCV values are close to 1 V. These results indicate that the 5CBCY gelcast electrolyte is obtained as a gastight ceramic part. The increase in temperature caused a higher power output Pmax from the investigated solid oxide fuel cells. A Pmax value of 20 mW cm−2 was obtained at 700 °C for a 5CBCY E-SOFC. Similar SOFC performance in analogous conditions was obtained from an E-SOFC involving a 5CBCY sample obtained via method B. The obtained values of 5CBCY E-SOFC performance are rather low due to the extreme thickness of the sample, which has a great impact on the total resistivity of the cell. The results of the electrochemical performance obtained for hydrogen–oxygen solid oxide fuel cells with 5CBCY electrolytes within the temperature range 500–700 °C were compared with the data in the literature for hydrogen–oxygen solid oxide fuel cells involving BaCeO3-based electrolytes, where anode and cathode materials were prepared from porous metallic (Ag, Pt) electrodes.

Voltage (U)–current (I) and power density (P)–current (I) curves recorded for hydrogen–oxygen solid oxide fuel cell (1)

Bonanos et al. [38] reported that electrolyte-supported solid oxide fuel cells involving BaCe0.9Gd0.1O3 (thickness ~ 1.2 mm), with porous silver as cathode material and Pt as anode material, exhibited a power output Pmax of ~ 20mW cm−2 at a temperature of 800 °C. Reduction in the thickness of a BaCe0.9Sm0.1O3 electrolyte to 0.5 mm enabled the acquisition of a Pmax value of approximately 200 mW cm−2 at 1000 °C from an SOFC with metallic electrodes (Ag cathode, Pt anode) [39].

One of the strategic goals leading to the improved performance of a SOFC with a 5CBCY electrolyte should be the identification of a suitable cathode material. The oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) occurring at the cathode of a SOFC causes most of the associated energy losses, leading to a reduction in the cell’s energy efficiency. In the case of a ceramic fuel cell with a proton-conducting ceramic membrane, water is formed on the cathode side, complicating the cathode reaction mechanism and resulting in a higher level of polarisation resistance in the cathode. In the previous paper [8], it was found that LSCF-5CBCY appeared to be a suitable cathode material for an E-SOFC involving 5CBCY as an electrolyte. In this study, we focused on electrochemical investigations of the BSCF|5CBCY interface.

The EIS spectra recorded for the cell with BSCF electrodes consist of three clearly separated semicircles (Fig. 12). The high-frequency (HF) semicircle is only partly visible within the spectra due to the limitations of the hardware in use; the medium frequency (MF) semicircle is well formed, whereas the low-frequency (LF) semicircle is scattered. The spectra were fitted using an EEC consisting of three resistor-and-capacitor (R, C) pairs connected in series. Instead of capacitors, constant phase elements (CPEs) were used. The impedance of the CPE can be expressed by the following formula [26]:

where j is an imaginary unit, f is the frequency, f0 is the frequency of reference, Ci is the capacitance at the frequency of reference, usually assumed to be f0 = 1000 Hz [26], index i is the number of the (R, CPE) pair (inset, Fig. 12) and α is a coefficient equal to 1 for an ideal capacitor, but usually with values in the range 0.8–1.0 or close to 0.5 for a diffusion process. The capacitances obtained for the HF semicircle fall within the range 32–94 nF cm−2, indicating that the HF semicircle represents the electrolyte grain boundary (GB) response [7]. The total 5CBCY electrolyte resistance Rs was calculated as the sum of R0 and R1. The capacitances obtained for the MF and LF semicircles belong to the range 0.42–0.63 mF cm−2 and 85–302 mF cm−2, respectively. These values indicate that MF and LF semicircles represent oxygen reduction reaction processes [40, 41]. The polarisation resistance Rp was calculated as the sum of R2 and R3. Resistances obtained by means of fitting impedance spectra are presented in Fig. 13. Resistances depend on oxygen partial pressure according to the equation

where a and m are coefficients. All resistances are weakly dependent on oxygen partial pressure. The coefficient m is equal to 0.019 and 0.061 for Rs and Rp, respectively. Electrolyte resistance should be independent of oxygen partial pressure within the examined range from 0.05 to 1. The weak dependence may indicate that this semicircle is overlapped by another semicircle representing the elementary step of the electrode reaction process [26]. The m coefficient obtained for Rp is much smaller than the value of 0.10 reported for a BSCF cathode examined with an SDC electrolyte [42]. This indicates that, in the case of a 5CBCY|BSCF interface, the two slowest oxygen reaction steps both involve an O2− ion rather than molecular or atomic oxygen [43]. The polarisation resistance is dependent to a slight degree on oxygen partial pressure and falls within a range from 0.24 to 0.30 Ω cm2 in the examined oxygen concentrations.

Example of the spectra of a BSCF electrode at 600 °C, open-circuit potential, and \(P_{{{\text{O}}_{2} }}\)P−1 = 0.1. Crosses indicate measured data; circles indicate fitted data; numbers above points denote logarithms of frequency. An equivalent electrical circuit was used to fit the data in the inset

Resistances and capacitances obtained by fitting impedance spectra versus oxygen partial pressure on a logarithmic scale, at 600 °C and open-circuit potential; R0—black squares, R1—blue circles, R2—green triangles, R3—pink triangles, C1—green diamonds, C2—navy-blue triangles, Rs—red triangles and Rp—violet circles. (Color figure online)

The EIS spectra recorded for a cell with porous platinum electrodes within a temperature range of 550–700 °C are presented in Fig. 14. Total 5CBCY electrolyte resistance Rs is assumed to be the resistance of the HF intercept of the spectra with the x axis, and to be equal to resistance R0, calculated with the use of the EEC (presented as the inset in Fig. 14) assumed for the spectra obtained in this series of experiments, whereas polarisation resistance Rp, assumed to represent the difference between the HF and LF intercepts with the x axis, is calculated as the sum of R1 and R2. Resistances Rs and Rp decrease with the increases in temperature (Fig. 15). The calculated activation energies for conductivities σs and σp equal to 0.52 and 0.71 eV, respectively. The obtained value of the activation energy of total 5CBCY conductivity, 0.52, agrees closely with the value of 0.53 measured by means of the four-probe DC method in dry air. A BSCF electrode connected with a 5CBCY electrolyte exhibits much lower polarisation resistance than a platinum electrode at 600 °C.

Conclusions

The results presented in this paper indicated the potential for forming Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 ceramic components by the gelcasting method, using methylcellulose as a gelling agent. It was found that the addition of 0.6% methylcellulose to slurries containing 35 vol% of ceramic powder resulted in a slow increase in viscosity compared to suspensions without it. On the basis of comparative DSC/TG curves registered for dried Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 cast samples, it was found that total mass losses at 1200 °C were approximately 11%. While heating dried 5CBCY cast samples in the temperature range of 25–1200 °C, decomposition of CaCO3 or BaCO3 was observed at temperatures higher than 800 °C. The presence of carbonates as secondary products of reaction between Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 and the CO2 phase is likely under these experimental conditions. The relative density of sintered 5CBCY gelcasted samples was ~ 94–95% and was comparable with samples prepared by isostatic pressing.

Analysis of the electrical conductivity of 5CBCY samples, as well as the electrochemical performance of 5CBCY-electrolyte-supported solid oxide fuel cells, indicated their suitability for application as components of electrochemical devices. In addition, the results of research on the electrolytic properties of 5CBCY ceramic parts indicate the need to undertake further research on the application of this method of formation in the manufacture of 5CBCY electrolytes as components for tubes or crucibles for use in electrochemical devices. Electrochemical studies showed that BSCF is a suitable cathode material for a 5CBCY electrolyte. At 600 °C, a cell with a BSCF cathode exhibits polarisation resistance within the range 0.24–0.30 Ω cm2 and weak dependency of oxygen partial pressure within the range 0.05–1 atm.

References

Vielstich W, Lamm A, Gasteiger HA. Handbook of fuel cells: fundamentals, technology and applications. New York: Wiley; 2003.

Yang J, Ji B, Si J, Zhang Q, Yin Q, Xie J, Tian C. Synthesis and properties of ceria based electrolyte for IT-SOFCs. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2006;41:15979–84.

Vladikova D, Stoynov Z, Chesnaud A, Thorel A, Viviani M, Barbucci A, Raikova G, Carpanese P, Krapchanska M, Mladenova E. Application of yttrium doped barium cerate for improvement of the dual membrane SOFC design. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2014;39:21561–8.

Hossain S, Abdalla AM, Jamain SN, Zaini JH, Azad AKA. review on proton conducting electrolytes for clean energy and intermediate temperature-solid oxide fuel cells. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;79:750–64.

Marrony M, editor. Proton-conducting ceramics: from fundamentals to applied research. New York: Pan Stanford; 2015.

Dudek M, Lis B, Rapacz-Kmita A, Gajek M, Raźniak A, Drożdż E. Some observations on the synthesis and electrolytic properties of (Ba1−xCax)(M0.9Y0.1)O3, M = Ce, Zr-based samples modified with calcium. Mater Sci Poland. 2016;34:101–14.

Dudek M, Lis B, Lach R, Daugėla S, Šalkus T, Kežionis A, Mosiałek M, Socha RP, Morgiel J, Gajek M, Sitarz M, Ziąbka M. Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 as an electrolyte for proton-conducting ceramic fuel cells. Electrochim Acta. 2019;304:70–9.

Lis B, Dudek M, Kluczowski R, Krauz M, Kawalec M, Mosiałek M, Lach R. Physicochemical properties of ceramic tape involving Ca0.05Ba0.95Ce0.9Y0.1O3 as an electrolyte designed for electrolyte-supported solid oxide fuel cells (IT-SOFCs). J Therm Anal Calorim. 2018;133:95–105.

Li G, Ren R. Preparation of 3YSZ-TZP solid electrolytes by gel casting technology. J Environ Sci. 2011;23:170–2.

Navarro ME, Capdevila XG, Morales M, Roa JJ, Segarra M. Manufacturing of anode-supported solid oxide fuel cells by a new shaping technique using aqueous gel-casting. J Power Sources. 2012;200:45–52.

Wiecinska P, Graule T, Bachonko M. Organic additives in gel-tape casting of ceramic powders—a novel approach to the problem of elasticity and cracking of thin tapes. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2015;35:3949–57.

Liu XL, Ma JF, Hou WH, Gao J. Fabrication of ceria-based electrolyte by gel-casting. Key Eng Mater. 2002;224–226:179–82.

Morales M, Navarro ME, Capdevila XG, Roa JJ, Segarra M. Processing of grade anode-supported micro-tubular solid oxide based on samaria-doped ceria via gel-casting and spray-coating. Ceram Int. 2012;38:3713–22.

Gao D, Guo R. Yttrium-doped barium zirconate powders synthesised by the gel-casting method. J Am Ceram Soc. 2010;93:1572–5.

Omatete OO, Janney MA, Nunn SD. Gelcasting: from laboratory development toward industrial production. J Eur Ceram Soc. 1997;17:407–13.

Chen Y, Xie Z, Yang J, Huang Y. Alumina casting based on gelation of gelatine. J Eur Ceram Soc. 1999;2:271–5.

Szuderska A, Mizerski T, Sakka Y, Szafran M. Application of new low toxic monomers in gelcasting process of alumina powder. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2011;18:1–4.

Hareesh UNS, Anantharaju R, Biswas P, Rajeswari K, Johnson R. Colloidal shaping of alumina ceramics by thermally induced gelation of methylcellulose. J Am Ceram Soc. 2011;94:749–53.

Sarkar N, Greminger GK. Methyl cellulose polymers as multifunctional processing aids in ceramic. Am Ceram Soc Bull. 1983;62:1280–4.

Hareesh UNS, Anantharaju R, Biswas P, Rajeswari K, Johnson R. Colloidal shaping of alumina ceramics by thermally induced gelation of methylcellulose. J Am Ceram Soc. 2011;94:749–53.

Cyster LA, Grant DM, Howdle SM, Rose FRAJ, Irvine DJ, Freeman D, Scotchford CA, Shakesheff KM. The influence of dispersant concentration on the pore morphology of hydroxyapatite ceramics for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:97–702.

Janney MA, Omatete OO, Walls CA, Nunn SD, Ogle RJ, Westmoreland G. Development of low-toxicity gelcasting systems. J Am Ceram Soc. 1998;81:581–91.

Lis B. Selected aspects of the design and diagnostics of solid oxide fuel cells. In: E3S Web Conf, vol 10, pp 1–7;2016.

Barbucci A, Bozzo R, Cerisola G, Costamagna P. Characterisation of composite SOFC cathodes using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Analysis of Pt/YSZ and LSM/YSZ electrodes. Electrochim Acta. 2002;47:2183–8.

James F, Roos M. Minuit a system for function minimalization and analysis of the parameter errors and correlations. Comput Phys Commun. 1975;10:343–67.

Mosiałek M, Nowak P, Dudek M, Mordarski G. Oxygen reduction at the silver|Gd0.2Ce0.8O1.9 interface studied by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and cyclic voltammetry at the silver point electrode. Electrochim Acta. 2014;120:248–57.

DiGiuseppe G, Sun L. Long-term SOFCs button cell testing. J Fuel Cell Sci Technol. 2014;11:1–5.

Rowe RC, Sheskey PJ, Quinn ME. Handbook of pharmaceutical excipients. 6th ed. London: Pharm Press American Pharm Assoc; 2009.

Kibbe H. Handbook of pharmaceutical excipients. 3rd ed. London: Am Pharm Assoc Pharm Press; 2000.

Besmann TM, Carneim RD, Armstrong TR. Decomposition of yttrium-doped barium cerate in carbon dioxide. In: Bose AC, editor. Inorganic membranes for energy and environmental applications. New York: Springer; 2009.

Lacz A. Effect of microstructure on chemical stability and electrical properties of BaCe0.9Y0.1O3−δ. Ionics. 2016;22:1405–14.

Ryu KH, Haile SM. Chemical stability and proton conductivity of doped BaCeO3–BaZrO3 solid solutions. Solid State Ionics. 1999;125:355–67.

Zając W, Rusinek D, Zheng K, Molenda J. Applicability of Gd-doped BaZrO3, SrZrO3, BaCeO3 and SrCeO3 proton conducting perovskites as electrolytes for solid oxide fuel cells. Cent Eur J Chem. 2013;11:471–84.

Biswas P, Rao YS, Johnson R. Processing of alumina honeycomb catalyst substrates and studies on methyl cellulose binder burn out kinetics. J Adv Catal Sci Technol. 2015;2:38–43.

Ding Y, Li Y, Huang W. The role of Ba concentration on the structural characteristics and electrical conductivities of BaxCe0.9Y0.1O3−α. Mater Res Bull. 2017;95:328–33.

Kulkarni S, Duttagupta S, Phatak G. Sol–gel synthesis and protonic conductivity of yttrium doped barium cerate. J Sol-Gel Sci Technol. 2015;74:94–102.

Amsif M, Marrero-Lopez D, Ruiz-Morales JD, Savvin SN, Gabás M, Nunez P. Influence of rare-earth doping on the microstructure and conductivity of BaCe0.9Ln0.1O3−δ proton conductors. J Power Sources. 2011;196:3461–9.

Bonanos N, Knight KS, Ellis B. Perovskite solid electrolytes: structure, transport properties and fuel cell applications. Solid State Ionics. 1995;79:161–70.

Iwahara H, Yajima T, Hibino T, Ushida H. Performance of solid oxide fuel cell using proton and oxide ion mixed conductors based on BaCe1−xSmxO3−δ. J Electrochem Soc. 1993;140:1687–93.

Baumann FS, Fleig J, Habermeier HU, Maier J. Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3−δ thin film microelectrodes investigated by impedance spectroscopy. Solid State Ionics. 2006;177:3187–91.

Giuliano A, Carpanese MP, Clematis D, Boaro M, Pappacena A, Deganello F, Liotta LF, Barbucci A. Infiltration, overpotential and ageing effects on cathodes for solid oxide fuel cells: La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3−δ versus Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3−δ. J Electrochem Soc. 2017;164:F3114–22.

Mosiałek M, Kędra A, Krzan M, Bielańska E, Tatko M. Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3−d–La0.6Sr0.4Co0.8Fe0.2O3−d composite cathode for solid oxide fuel cell. Arch Metall Mater. 2016;61:1137–42.

Wang Y, Zhang L, Chen F, Xia C. Effects of doped ceria conductivity on the performance of La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3−d cathode for solid oxide fuel cell. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2012;37:8582–91.

Acknowledgements

This paper was carried out under a contract (11.11.210.217) with the AGH University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Energy and Fuels, Cracow, Poland. Some measurements were performed using scientific equipment belonging to the laboratories of the AGH-UST Energy Centre, Cracow, Poland. M. Mosiałek acknowledge the European Union Erasmus + programme (project number: 2017-1-PL01-KA103-035642) for providing scholarship (financial support) for the research/mobility/training.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dudek, M., Lis, B., Kocyło, E. et al. Utilisation of methylcellulose as a shaping agent in the fabrication of Ba0.95Ca0.05Ce0.9Y0.1O3 proton-conducting ceramic membranes via the gelcasting method. J Therm Anal Calorim 138, 2077–2090 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08856-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08856-8