Abstract

A series of Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped calcium molybdato-tungstates, i.e., Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x (0 < x ≤ 0.2222 when y = 0.0200 and 0 < y ≤ 0.0667 when x = 0.1667, ⌷ represents vacancy) materials were successfully synthesized via high-temperature annealing. XRD results confirmed the formation of single, tetragonal scheelite-type phases (space group I41/a). A change in both lattice constants (a and c), lattice parameter ratio c/a and progressive deformation of MoO4/WO4 tetrahedra with increasing Eu3+ as well as Mn2+ contents were observed. The melting point of doped materials is lower than the melting point of pure matrix, i.e., CaMoO4. New materials exhibit strong absorption in the UV range. They are insulators with the optical direct band gap (Eg) higher than 3.50 eV. The Eg values nonlinearly change with increasing dopants concentrations. EPR measurements allowed to establish the nature of magnetic interactions among Mn2+ ions. Additionally, EPR spectra were sensitive on both parameters: Mn2+ and Eu3+ concentration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Metal molybdates and tungstates were proved to be excellent host lattice of luminescent materials due to their high thermal stability and chemical tolerance. These compounds show many different types of structures, i.e., scheelite (I41/a, No. 88), pseudo-scheelite (Pnma, No. 62), wolframite (P2/c, No. 13), zircon (I41/amd, No. 141) and fergusonite (C2/c, No. 15) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Most divalent metal molybdates and tungstates take scheelite-type or scheelite-related structure. Scheelite-type A(Mo,W)O4 compounds possess eight symmetry elements, a body-centered unit cell and four molecules per one unit cell [1,2,3, 6, 7]. Each A-site divalent ion is surrounded by eight oxygen anions and forms AO8 dodecahedra [1,2,3, 6, 7]. Each Mo6+ or W6+ ion is coordinated to four oxygen ions forming (Mo,W)O4 tetrahedron [1,2,3, 6, 7].

Materials doped with trivalent rare-earth (RE) ions have been studied for many applications, such as lasers, solid state lightings, display panels and optical amplifiers [8]. Among of trivalent RE ions, Eu3+ ion is characterized by the lowest excited level 5D0 of 4f6 configuration and displayed mainly very sharp red light emission centered at 615 nm ascribed to the 5D0 → 7F2 transition [9]. Divalent manganese ion plays an important role in some inorganic phosphors. It can produce a broad emission due to the transition from 4T1 to 6A1 level. The emission color strongly depends on a crystal field strength as well as coordination number of Mn2+, and it varies from green (tetrahedral coordination of manganese ions) to red (octahedrally coordinated Mn2+) [10,11,12,13,14]. Thus, simultaneously doping the host material with Eu3+ and Mn2+ ions allows to energy transfer from Mn2+ to Eu3+ ions and improve the luminescent efficiency of doped samples [15, 16].

In our earlier papers, we have focused on three scheelite-type matrices, i.e., CdMoO4, PbMoO4 and PbWO4. Our studies have shown the existence of new scheelite-type solid solutions described by the following chemical formulas: (Cd,Pb)1−3x⌷xRE2xMoO4 and (Cd,Pb)1−3x⌷xRE2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x, where RE = Pr–Yb [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. The substitution of divalent Cd2+ or Pb2+ ions by trivalent rare-earth ones is connected with a charge-compensating defect. Charge balance is achieved by the formation of A-site vacancies, which is denoted by us as ⌷, i.e., 3 Cd2+(Pb2+) → 2 RE3+ + ⌷. Presence of these vacancies is seen in the dependence of wavenumber and integral intensity of some electronic absorption, IR and Raman bands on increasing concentration of the point defects in the RE3+-doped materials. The presence of vacancies results also in significant deformation of the crystal lattice, particularly around RE3+ ions, and which results in the emission of broadbands associated with f–f transitions in RE3+ ions [19,20,21]. The RE3+-doped molybdates or molybdato-tungstates are promising laser materials, phosphors and good microwave dielectric microcrystalline ceramics for band-pass filters, resonators and antenna switches (mobile and satellite communication) [19,20,21,22].

In this work, microcrystalline samples of new Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x solid solution with different Mn2+ (y = 0.0066; 0.0200; 0.0333; 0.0667) as well as Eu3+ (x = 0.0005; 0.0025; 0.0050; 0.0098; 0.0283; 0.0455; 0.0839; 0.1430; 0.1667; 0.1970; 0.2059; 0.2222) contents were successfully obtained by a high-temperature sintering. Their structure, thermal stability and optical properties were examined. Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR) was used to determine the types of magnetic interactions and the local symmetry of Mn2+ ions.

Experimental

Synthesis of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x

New microcrystalline Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped calcium molybdato-tungstates with the following formula of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x were obtained by the two-step synthesis, in which both the steps consist of high-temperature sintering which is very often used in a preparation of many molybdates and tungstates [27,28,29,30,31,32]. The following reactants were used in the first step of synthesis: CaCO3, MnO, MoO3, Eu2O3 and WO3 (all raw materials of high-purity grade min. 99.95%, Alfa Aesar or Fluka, and without thermal pre-treatment). Calcium molybdate (CaMoO4), manganese molybdate (MnMoO4) as well as europium tungstate Eu2(WO4)3 were obtained according to the procedure used by us in previous studies [26, 32]. In the next step of synthesis, we prepared 15 ternary mixtures containing MnMoO4, Eu2(WO4)3 and CaMoO4. The concentrations of manganese molybdate and europium tungstate in each initial MnMoO4/Eu2(WO4)3/CaMoO4 mixture are shown in Table 1. The initial mixtures, not compacted to pellets, were heated in air, in ceramic crucibles, in several 12-h annealing stages, and at temperatures in the range of 1173–1473 K. After each heating period, obtained materials were cooled down to ambient temperature, weighed, ground in an agate mortar, followed by examination for their composition by XRD method. The mass change control of doped samples showed a slight mass loss observed for each material that did not exceed the value of 0.26%. This observation suggests that a synthesis of new materials runs practically without their mass change.

Methods

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of new doped materials were collected within the 2θ range of 10°–100° and under ambient conditions by using an EMPYREAN II diffractometer (PANalytical) and CuKα1,2 radiation (the scanning step 0.013°). High Score Plus 4.0 software was used to analyze registered XRD patterns. Lattice parameters were calculated using the procedure described and used in our previous works [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, 32]. Quantachrome Instruments Ultrapycnometer (model Ultrapyc 1200 e) was used to measure the density of each sample. As the pycnometric gas, nitrogen (purity 99.99%) was used. DTA-TG studies of manganese molybdate and europium tungstate were carried out on a TA Instruments thermoanalyzer (model SDT 2960) at the heating rate of 10 K min−1, and in the temperature range from 293 to 1473 K (the air flow 110 mL min−1). Melting point of some Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped ceramic materials was determined by using a pyrometric method. Selected samples, previously compressed into pellets, were heated in a resistance furnace, and their image was simultaneously recorded by a camera. Melting point of a sample was determined at the time when its image was not seen in a camera. IR spectra were recorded within the spectral range of 1500–200 cm−1 on a Specord M-80 spectrometer (Carl Zeiss Jena) using pellets with potassium bromide. UV–Vis reflectance spectra were recorded within the range of 200–1000 nm using JASCO-V670 spectrophotometer containing an integrating sphere. EPR spectra of Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped samples were determined by an X-band Bruker ELEXSYS E 500 CW spectrometer operating at 9.5 GHz with 100 kHz magnetic field modulation. Temperature dependence of the EPR spectra of doped materials within the 78–300 K temperature range was recorded using Oxford Instruments ESP liquid nitrogen and helium cryostat.

Results and discussion

XRD analysis

The powder diffraction patterns of pure CaMoO4 and Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1–3x(WO4)3x ceramics with different contents of europium(III) and manganese ions, i.e., when x = 0.0005; 0.0025; 0.0050; 0.0098; 0.0283; 0.0455; 0.0839; 0.1430; 0.1667; 0.1970; 0.2059; and 0.2222 for constant Mn2+ content (y = 0.0200) as well as when y = 0.0066; 0.0200; 0.0333; and 0.0667 for constant Eu3+ concentration (x = 0.1667) are shown in Fig. 1a, b. XRD analysis shows the powder diffraction patterns of Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped calcium molybdato-tungstates consisted of diffraction lines which can be attributed to scheelite-type framework. No impurity phases, i.e., initial reactants, oxides (Eu2O3, MnO, CaO, MoO3 and WO3), and other europium tungstates or molybdates were observed with increasing Eu3+ concentration only up to x = 0.2222 (40.00 mol% of Eu2(WO4)3 in initial MnMoO4/Eu2(WO4)3/CaMoO4 mixtures when y = constant). No additional phases we have also observed on the powder diffraction patterns of doped materials when Mn2+ content was only up to y = 0.0667 (10.00 mol% of MnMoO4 when x = 0.1667). The observed peaks attributed to scheelite-type structure shifted toward lower 2θ angle with increasing Eu3+ concentration (Fig. 1a) or toward higher 2θ angle with increasing Mn2+ content (Fig. 1b). All observed diffraction lines were successfully indexed to the pure tetragonal scheelite-type structure with space group I41/a (No. 88, CaMoO4—JCPDs No. 04-013-6763). This fact confirmed the formation of new solid solution of MnMoO4 and Eu2(WO4)3 in CaMoO4 matrix. The diffraction patterns of samples comprising initially above 40.00 mol% Eu2(WO4)3 in MnMoO4/Eu2(WO4)3/CaMoO4 mixtures (not presented in the paper) revealed simultaneously peaks which can be ascribed to the saturated solid solution, i.e., Ca0.3134Mn0.0200⌷0.2222Eu0.4444(MoO4)0.3334(WO4)0.6666 (x = 0.2222) as well as the diffraction lines characteristic of Eu2(WO4)3. It means that the solubility limit of europium tungstate in structure of CaMoO4 when the concentration of MnMoO4 equals 3.00 mol% is not higher than 40.00 mol%. On the other hand, the diffraction patterns of samples with an initial content of manganese molybdate above 10.00 mol% showed diffraction lines attributed to Ca0.4332Mn0.0667⌷0.1667Eu0.3334(MoO4)0.4999(WO4)0.5001 (y = 0.0667) as well as the diffraction lines characteristic of MnMoO4. It means that the solubility limit of manganese molybdate in structure of CaMoO4 when the initial concentration of Eu2(WO4)3 equals 25.00 mol% is not higher than 10.00 mol%.

The lattice constants calculated on the basic of XRD data for CaMoO4 as well as for Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped ceramics are presented in Table 1. Both unit cell parameters (a and c) of doped materials gradually increased with increasing Eu3+ concentration when Mn2+ content in samples was constant (y = 0.0200). This is not a typical situation because bigger Ca2+ ions (112 pm for CN = 8) in the matrix were substituted by much smaller Eu3+ ones (106.6 pm for CN = 8) [33]. We have already observed this phenomenon in other RE3+-doped and vacancied materials, i.e., Cd1–3x⌷xDy2xMoO4 [22]. The lattice parameters of all doped samples decreased gradually with increasing Mn2+ concentration for the materials with constant Eu3+ content (Table 1). It is a consequence of the substitution of big Ca2+ ions by much smaller Mn2+ ones (96 pm for CN = 8). In all scheelite-type molybdates and tungstates, Mo6+ and W6+ ions are tetrahedrally coordinated by oxygen ones and their ionic radii are 41 and 42 pm, respectively [33]. Thus, the substitution of Mo6+ by W6+ observed in Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1–3x(WO4)3x materials did not cause any visible changes in both lattice constants. Only a parameter as well as the volume of tetragonal cell (V) calculated for doped ceramics (when Eu3+ concentration was increasing and Mn2+ content was constant) obeys the Vegard’s law, i.e., they are nearly linear functions of x parameter (Fig. 2). The c parameter changes clearly nonlinearly with increasing Eu3+ content in the samples (Fig. 3, Table 1). In contrast, the lattice parameters (both a and c) as well as the volume of cell calculated for doped samples (when Mn2+ content was increasing and Eu3+ concentration was constant) obey the Vegard’s law when 0 < y ≤ 0.0667 (Figs. 4, 5). We also calculated the lattice parameter ratio c/a for two series of Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped ceramics (Figs. 3, 5). This parameter clearly nonlinearly changes with increasing x (Fig. 3) as well as practically linearly decreases with increasing y (Fig. 5). It means that in whole homogeneity range of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1–3x(WO4)3x solid solution we have observed a deformation of tetragonal scheelite-type cell of each doped sample in comparison with the tetragonal cell of pure CaMoO4. The experimental density values determined for each sample under study are given in Table 1. The density of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1–3x(WO4)3x samples almost linearly increases with increasing Eu3+ as well as Mn2+ content (Table 1).

Thermal stability of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x materials

Appropriate thermal studies of new Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped microceramics have been preceded by DTA experiments for some initial reactants, i.e., MnMoO4 and Eu2(WO4)3, due to the fact that information on their thermal properties is not completely, contrary or unknown. Figure 6a shows DTA curve of MnMoO4 recorded during controlled heating up to 1473 K. The single and very sharp endothermic effect with its onset at 1412 K is due to congruent melting of monoclinic manganese molybdate (a = 4.818(1) Å, b = 5.759(1) Å, c = 4.965(1) Å, β = 90.82(1)°, Z = 2, space group P2/c [34]). Only one endothermic peak is observed on DTA curve recorded during controlled heating of Eu2(WO4)3 (Fig. 6b). This effect with its onset at 1426 K is connected with congruent melting of monoclinic europium tungstate (a = 7.676(3) Å, b = 11.463(3) Å, c = 11.396(5) Å, β = 109.63(4)°, Z = 4, space group C2/c [35]). In contrary to isostructural Gd2(WO4)3, europium tungstate does not show polymorphism [35]. Crystallization process of Eu2(WO4)3 from a melt observed during controlled cooling (exothermic effect) is quite significantly shifted toward lower temperatures, and it starts at 1408 K. Pure matrix of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x solid solution, i.e., CaMoO4 melts congruently at 1753 K and this temperature has already been determined in our previous studies by using a pyrometric method [32]. Melting point of some Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped materials has also been determined by using the same method. These values are lower than the melting point of CaMoO4, and they are as follows: 1653 K (x = 0.0455, y = 0.0200), 1578 K (x = 0.1430, y = 0.0200), 1528 K (x = 0.1970, y = 0.0200), 1503 K (x = 0.2222, y = 0.0200) and 1518 K (x = 0.1667, y = 0.0667). Figure 7 shows powder diffraction patterns of some initial Mn2+- and Eu3+-doped materials as well as resulting melts obtained after their pyrometric studies. According to XRD analysis, the patterns of each melt consisted of only diffraction lines which can be attributed to a scheelite-type framework. However, the observed peaks shifted toward lower or higher 2Θ angle in comparison with diffraction lines recorded on the powder XRD patterns of initial Mn2+- and Eu3+-doped materials.

IR spectra

Figures 8 and 9 show the IR spectra of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1–3x(WO4)3x microceramics with different contents of Eu3+ as well as Mn2+ ions, respectively. Molybdates and tungstates with scheelite-type structure are characterized by molecules containing XO4 (X = Mo or W) tetrahedra showing strong covalent X–O bonds. For scheelite-type materials, the frequencies active in IR are observed within the spectral region of 900–700 cm−1 (ν1(A1)—symmetric—as well as ν3(F2)—asymmetric stretching modes) and 450–250 cm−1 (ν2(E1)—symmetric—and ν4(F2)—asymmetric bending modes) [36,37,38,39,40,41]. Figures 8 and 9 show IR spectra of pure CaMoO4 and Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped materials. Strong and narrow absorption bands observed in the IR spectra of CaMoO4 at 868 and 810 cm−1 can be assigned to the stretching modes of Mo–O bonds in MoO4 tetrahedra [36,37,38,39,40,41]. The bands with their maximum at 427 and 324 cm−1 can be related to the binding modes of Mo–O bonds in MoO4 tetrahedra [36,37,38,39,40,41]. The experimental results for calcium molybdate confirm a presence of only regular molybdate tetrahedra occupying sites of a cubic point symmetry Td characteristic for scheelite-type structure [36,37,38,39,40,41]. The IR spectra of doped ceramics show differences in an intensity and a width of observed absorption bands compared to those ones registered for pure matrix. They are wide and exhibit very low intensity. Additionally, with increasing content of Eu3+ in doped materials, the absorption bands moved toward higher wave numbers (Fig. 8). This phenomenon is clearly visible for bands due to bending vibrations of Mo–O bonds in MoO4 tetrahedra (Figs. 8, 9). It suggests the presence of tungstate tetrahedra in a crystal lattice of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1–3x(WO4)3x. For the samples when x ≥ 0.1430 we can observe additional absorption bands within the region of 940–915 cm−1 (Figs. 8, 9). This fact suggests the presence of other types of MoO4 and WO4 tetrahedra, i.e., distorted molybdate and tungstate anions. Deformation of the shape of both anions, i.e., changes in X–O and O–X–O bond lengths and/or angles in XO4 tetrahedra, compared to the shape of regular ones is a result of a presence of vacancies near corners of MoO4 or WO4 polyhedra. This deformation of regular tetrahedral shape of molybdate anions had already been observed in vacancied scheelite-type cadmium molybdates doped with RE ions, i.e., Cd0.25⌷0.25RE0.50MoO4, where RE = Pr, Nd, Sm–Dy as well as for Cd1−3x⌷xGd2xMoO4 [42, 43].

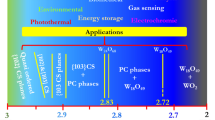

Optical properties of Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped ceramics

Optical energy band gap (Eg) of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x ceramics was determined by the method first used by Kubelka and Munk [44] and next applied by many authors [22,23,24,25, 32, 45,46,47,48,49]. This method is based on a transformation of diffuse reflectance spectra to estimate band gap energy values. In a case of parabolic band gap structure, an optical energy band gap as well as an absorption coefficient of material (α) can be calculated using the equation proposed by Tauc et al. [50, 51]:

where h is the Planck constant, ν is the light frequency, A is the proportionally coefficient characteristic for material under study, and n is the constant determined by an electronic transition type, and it can reach the following values: 1/2, 3/2, 2 and 3 for allowed directly, forbidden directly, allowed indirectly and forbidden indirectly transition, respectively [50, 51]. As it is known from literature information, all alkaline earth metal molybdates and tungstates with the tetragonal scheelite-type structure exhibit an optical absorption spectrum governed by direct absorption transition (n = 1/2). It means that an electron located in a maximum energy state in a valence band reaches a minimum energy state in a conduction band under the same point in the Brillouin zone [52,53,54,55,56]. Thus, the optical band gap of materials can be determined from the plots of (αhν)2 as a function of photon energy (hν) by extrapolating the linear portion of the curve to intersect the hν axis at zero absorption [22,23,24,25, 32, 45,46,47,48,49, 52,53,54,55,56]. Figures 10 and 11 show UV–Vis absorption spectra of pure CaMoO4 and Mn2+- and Eu3+-doped materials recorded within the spectral range of 200–800 nm. All samples show energy absorption ability in the UV region, and the absorption edge is near to 325 or 350 nm. The plots (αhν)2 versus hν and the extrapolated direct energy band gap Eg values are shown in Figs. 12 and 13 as well as are given in Table 1, respectively. The Eg values of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x ceramics are lower than the adequate value for pure matrix, and they nonlinearly change with increasing Eu3+ content when Mn2+ concentration was constant. We have also observed the same nonlinear dependence of Eg with increasing Mn2+ content when Eu3+ concentration was constant. The lowest value of Eg (3.46 eV) was found for the sample with x = 0.1970 and y = 0.0200 (Table 1).

EPR results

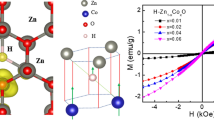

A group of doped materials with formula of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x with different combination of x and y parameters were studied using the EPR technique. Resonance spectra detected at temperature range of 78–300 K revealed an existence of multiline signal centered near 340 mT magnetic field (Figs. 14, 15). Observed resonance signal could be ascribed to the Mn2+ magnetic ions. Manganese metal is characterized by electronic spin value S = 5/2, giving usually a single asymmetric line in EPR experiment. But mentioned ion possesses nuclear spin value I = 5/2, resulting with characteristic splitting of the resonance signal to form six narrow lines.

Figure 14 presents an arrangement of chosen EPR spectra detected at c.a. 80 K for samples with various manganese ion doping represented by y parameter, but with constant europium ion concentration x = 0.1667.

As could be seen in Fig. 14, for samples with lower Mn2+ doping the obtained EPR signal possesses six quite well-resolved lines originated from hyperfine interactions between electronic and nuclear magnetic moment of Mn2+ ions. But such model works properly only for low-density Mn2+ ions. With increasing manganese content, the arrangement of Mn2+ ions starts to be systematically disturbed, finally giving only single wide resonance line for samples with y parameter above 0.0200.

Figure 15 shows the evolution of EPR spectra under europium doping variation, represented by x parameter, while manganese ion concentration is maintained at constant value y = 0.0200. As could be seen, relatively low Eu3+ concentration gives no influence on the manganese ions. Thus, a well-resolved hyperfine structure of six narrow lines is observed. Increase in europium doping leads to situation, where resonance signal is systematically overleaped. For x value 0.2222 and higher, the sixfold arrangement is invisible and the manganese signal consists of only one wide line.

Influence of y parameters on the EPR signal seems to be very expectable. If concentration of manganese is maintained below some critical value, magnetic system of Mn2+ ions could be described with model of isolated magnetic ions with Zeeman interaction, disturbed only by hyperfine interaction of Mn2+ nuclear spin. Increasing concentration of manganese leads to perturbation of the simple magnetic model. Additional interactions, mainly exchange and dipolar nature, result in widening and overleaping the overall resonance signal.

Coexistence of Eu3+ ions apparently gives no influence on the magnetic system of Mn2+, as trivalent europium is non-magnetic. But results shown in Fig. 15 indicate progressive disturbance of manganese system by the increase in europium ion concentration. Due to comparable ionic size, doped Eu3+ ions are incorporated into the Mn2+ positions. It leads to generation of charge unequilibrium areas (vacancies) localized near such manganese position. Obviously, number of vacancies directly depends on the level of Eu3+ concentration, and it increases with increasing x parameter. Thus, vacancy states are denoted in the proposed formula as ⌷x.

With higher number of vacancies, their localization near Eu3+ ions becomes less restrict. Due to charge compensation effect, vacancies could appear in other places, also near existed Mn2+ ions. Interaction between vacancies and manganese disturbs the Mn2+ electronic structure. Thus, with increasing x parameter, the EPR signal of Mn2+ ions starts to overleap, as is visible in Fig. 15.

Temperature dependence of the EPR signal intensity usually allows to describe the nature of interactions between responsible magnetic particles. All studied samples revealed decrease in the signal intensity (IEPR) with increasing temperature according to the Curie–Weiss law:

where C is the parameter connected with concentration of magnetic ions and θ is the parameter describing the sign of magnetic interactions.

According to Eq. 2, magnetic arrangement created by manganese ions revealed a strong antiferromagnetic (AFM) interaction proved by significant negative value of θ parameter for all samples. Generally, with increasing concentration of Mn2+ or Eu3+ the strength of AFM interaction increases, too. Figure 16a shows temperature dependence of the resonance signal and adequate fitting done using Eq. 2 for sample: Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x with x = 0.0283 and y = 0.0200. The sign of magnetic interactions could be also concluded from drawing of IEPR.T product as a function of temperature (Fig. 16b). Positive loops of calculated values indicate negative value of θ parameter, i.e., domination of AFM interactions among responsible Mn2+ ions.

a Intensity of the EPR signal as a function of temperature for sample x = 0.0283, y = 0.0200 (points) and fitting the result using Eq. 1 (line). b Dependence of IEPRT product as a function of temperature for sample x = 0.0005 and y = 0.0200

As we mentioned earlier, magnetic properties of manganese ions could be described by Zeeman and hyperfine interactions. Enriched spin-Hamiltonian, including additional interactions with crystal field (fine interactions), should has the following form:

where the first term represents the Zeeman interaction, the second zero-field splitting, the third hyperfine interaction and the last one higher-order fine interactions represented by Stevens operators.

In the case of axial or rhombic symmetry near magnetic particle, the zero-field splitting term could be expressed by standardized form using scalar D value and E parameter represented rhombic distortion near responsible magnetic ions. Thus, useful form of spin-Hamiltonian describing Mn2+ ions has the form:

Equation 4 is employed to simulate the EPR spectra in order to establish: g, D, E, A and B kq values. Simulation was done using EPR–NMR program [57]. As we already mentioned, the proposed model seems to be proper only for lower x and y values. Figure 17 presents the best comparison between experimental and simulated spectra using Eq. 4 for sample x = 0.0098, y = 0.0200. As could be seen, adjustment is quite good. Spin-Hamiltonian values calculated for this case are given in Table 2. Other B kq parameters are negligible, E = 0. The proposed model is not perfect, but values gi and Ai are typical for Mn2+ ions. From the other hand, zero-field splitting parameter with Dx = Dy indicates an axial symmetry near manganese ions crystallographic positions.

EPR spectrum of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x with x = 0.0098, y = 0.0200 (black line) and spectrum simulated using Eq. 3 (red line)

Conclusions

In summary, samples of new Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped calcium molybdato-tungstates with the formula of Ca1−3x−yMny⌷xEu2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x, where ⌷ represents vacancy with different Mn2+ (y = 0.0066; 0.0200; 0.0333; 0.0667) as well as Eu3+ (x = 0.0005; 0.0025; 0.0050; 0.0098; 0.0283; 0.0455; 0.0839; 0.1430; 0.1667; 0.1970; 0.2059; 0.2222) contents, were successfully obtained by a high-temperature sintering. The XRD patterns showed that doped materials have tetragonal, body-centered scheelite-type structure with space group I41/a. The melting point of each Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped material is lower than the melting of pure matrix (CaMoO4, 1753 K), and it strongly depends on Mn2+ as well as Eu3+ contents in scheelite-type framework. IR results confirmed the presence of MoO4 and WO4 tetrahedra, the deformation of their shape in comparison with the tetrahedral shape of regular MoO4 and WO4 polyhedra as well as very weak covalent nature of Mo–O and W–O bonds in doped materials. The Tauc plots were used to extrapolate a direct band gap of new ceramics. They are insulators with the optical direct band gap higher than 3.50 eV. For all doped ceramics, Eg values are lower than the direct band gap of pure matrix and they change nonlinearly with increasing Mn2+ and Eu3+ contents. EPR spectra confirmed the existence of magnetic species in the form of Mn2+ ions. Manganese ions behave as isolated magnetic centers, if concentration of Mn2+ is low. These ions are characterized by close to axial local symmetry, with significant AFM interactions among each other. Increasing manganese ions concentration leads to significant changes in a simple magnetic arrangement, where above y = 0.0200 a complex magnetic system of manganese is created. From the other hand, magnetic arrangement should be also changed by increasing concentration of europium ions. In this case, Eu3+ ions have influence on magnetic system by indirect interactions with Mn2+ ions. Model with isolated manganese species is changed at europium concentration above x = 0.2222.

References

Sleight AW. Accurate cell dimensions for ABO4 molybdates and tungstates. Acta Crystallogr. 1972;B28:2899–902.

Santamaria-Perez D, Errandonea D, Rodriguez-Hernandez P, Munoz A, Lacomba-Perales R, Polian A, Meng Y. Polymorphism in strontium tungstate SrWO4 under quasi-hydrostatic compression. Inorg Chem. 2016;55:10406–14.

Cavalcante LS, Longo VM, Sczancoski JC, Alemeida MAP, Batista AA, Varela JA, Orlandi MO, Longo E, Siu Li M. Electronic structure, growth mechanism and photoluminescence of CaWO4 crystals. CrystEngComm. 2012;14:853–68.

Macavei J, Schulz H. The crystal structure of wolframite type tungstates at high pressure. Z Krystall. 1993;207:193–208.

Christofilo D, Ves S, Kourouklis GA. Pressure induced phase transitions in alkaline earth tungstates. Phys Status Solidi B. 1996;198:539–44.

Daturi M, Busca G, Borel MM, Leclaire A, Piaggio P. Vibrational and XRD study of the system CdWO4–CdMoO4. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:4358–69.

Manjon FJ, Errandonea D, Garro N, Pellicer-Porres J, López-Solano J, Rodríguez-Hernández P, Radescu S, Mujica A, Muñoz A. Lattice dynamics study of scheelite tungstates under high pressure II. PbWO4. Phys Rev B. 2006;74:112–44.

Ronda CR, Jüstel T, Nikol H. Rare earth phosphors: fundamentals and applications. J Alloys Compd. 1998;277(275):669–76.

Czajka J, Piskuła Z, Szczeszak A, Lis S. Structural, morphology and luminescence properties of mixed calcium molybdate-tungstate microcrystals doped with Eu3+ ions and changes of the color emission chromaticity. Opt Mater. 2018;84:426–33.

Cao R, Wang W, Zhang J, Ye Y, Chen T, Guo S, Xiao F, Luo Z. Luminescence properties of Sr2Mg3P4O15:Mn2+ phosphor and the improvement by co-doping Bi3+. Opt Mater. 2018;79:223–6.

Kubus M, Castro C, Enseling D, Jüstel T. Room temperature red emitting carbodiimide compound Ca(CN2):Mn2+. Opt Mater. 2016;59:126–9.

Han B, Li P, Zhang J, Jin L, Luo W, Shi H. β-Zn3BPO7:Mn2+: a novel rare-earth-free possible deep-red emitting phosphor. Opt Mater. 2015;42:476–8.

Cao R, Shi Z, Quan G, Hu Z, Zheng G, Chen T, Guo S, Ao H. Rare-earth free broadband Ca3Mg3P4O16:Mn2+ red phosphor: synthesis and luminescence properties. J Lumin. 2018;194:542–6.

Chen C, Cai P, Qin L, Wang J, Bi S, Huang Y, Seo HJ. Luminescence properties of sodalite-type Zn4B6O13:Mn2+. J Lumin. 2018;199:154–9.

Song E, Zhao W, Dou X, Zhu Y, Yi S, Min H. Nonradiative energy transfer from Mn2+ to Eu3+ in K2CaP2O7:Mn2+, Eu3+ phosphor. J Lumin. 2012;132:1462–7.

Katayama Y, Kayumi T, Ueda J, Tanabe S. Enhanced persistent red luminescence in Mn2+-doped (Mg, Zn)GeO3 by electron trap and conduction band engineering. Opt Mater. 2018;79:147–51.

Tomaszewicz E, Filipek E, Fuks H, Typek J. Thermal and magnetic properties of new scheelite type Cd1–3x⌷xGd2xMoO4 ceramic materials. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2014;34:1511–22.

Tomaszewicz E, Dąbrowska G, Filipek E, Fuks H, Typek J. New scheelite-type Cd1–3x⌷xRE2x(MoO4)1−3x(WO4)3x ceramics—their structure, thermal and magnetic properties. Ceram Int. 2016;42:6673–81.

Guzik M, Tomaszewicz E, Guyot Y, Legendziewicz J, Boulon G. Eu3+ luminescence from different sites in scheelite-type cadmium molybdate red phosphor with vacancies. J Mater Chem C. 2015;3:8582–94.

Guzik M, Tomaszewicz E, Guyot Y, Legendziewicz J, Boulon G. Structural and spectroscopic characterizations of new vacancied Cd1−3xNd2x⌷xMoO4 scheelite-type molybdates as potential optical materials. J Mater Chem C. 2015;3:4057–69.

Guzik M, Tomaszewicz E, Guyot Y, Legendziewicz J, Boulon G. Spectroscopic properties, concentration quenching and Yb3+ site occupations in a vacancied scheelite-type molybdates. J Lumin. 2016;169:755–64.

Tomaszewicz E, Piątkowska M, Pawlikowska M, Groń T, Oboz M, Sawicki B, Urbanowicz P. New vacancied and Dy3+-doped molybdates—their structure, thermal stability, electrical and magnetic properties. Ceram Int. 2016;42(16):18357–67.

Piątkowska M, Tomaszewicz E. Synthesis, structure and thermal stability of new scheelite-type Pb1–3x⌷xPr2x(MoO4)1–3x(WO4)3x ceramic materials. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;126(1):111–9.

Piątkowska M, Tomaszewicz E. Solid-state synthesis, thermal stability and optical properties of new scheelite-type Pb1–3x⌷xPr2xWO4 ceramics. Mater Lett. 2016;182:332–5.

Piątkowska M, Fuks H, Tomaszewicz E, Kochmańska AE. New vacancied and Gd3+-doped lead molybdato-tungstates and tungstates prepared via solid state and citrate-nitrate combustion method. Ceram Int. 2017;43(10):7839–50.

Pawlikowska M, Piątkowska M, Tomaszewicz E. Synthesis and thermal stability of rare-earths molybdates and tungstates with fluorite and scheelite-type structure. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;130(1):69–76.

Keskar M, Krishnan K, Phatak R, Dash S, Sali SK, Kannan S. Studies on thermophysical properties of the ThW2O8 and UWO6. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;126(2):659–70.

Yanase I, Ootomo R, Kobayashi H. Effect of B substitution on thermal changes of UV–Vis and Raman spectra and color of Al2W3O12 powder. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2018;132:1–6.

Łącz A, Bak B, Lach R. Structure, microstructure and physicochemical properties of BaW1−xNbxO4−δ materials. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2018;133(1):107–14.

Tabero P, Frąckowiak A. Reinvestigations of the Li2O–WO3 system. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;130(1):311–8.

Tabero P, Frąckowiak A. Synthesis of Fe8V10W16O85 by a solution method. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;125(3):1445–51.

Pawlikowska M, Fuks H, Tomaszewicz E. Solid state and combustion synthesis of Mn2+-doped scheelites—their optical and magnetic properties. Ceram Int. 2017;43(16):14135–45.

Shannon RD. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr A. 1976;32:751–67.

Clearfield A, Moini A, Rudolf PR. Preparation and structure of manganese molybdates. Inorg Chem. 1985;24:4606–9.

Tomaszewicz E, Fuks H, Typek J, Sawicki B, Oboz M, Groń T, Mydlarz T. Preparation, thermal stability and magnetic properties of new AgY1−xGdx(WO4)2 ceramic materials. Ceram Int. 2015;41(4):5734–48.

Liegeois-Duyckaerts M, Tarte P. Vibrational studies of molybdates, tungstates and related compounds—II: new Raman data and assignments for the scheelite-type compounds. Spectrochim Acta A. 1972;28(11):2037–51.

Brown RG, Denning J, Hallett A, Ross SD. Forbidden transitions in the infra-red spectra of tetrahedral anions—VIII: spectra and structures of molybdates, tungstates and periodates of the formula MXO4. Spectrochim Acta A. 1970;26(4):963–70.

Tarte P, Liegeois-Duyckaerts M. Vibrational studies of molybdates, tungstates and related compounds—I: new infrared data and assignments for the scheelite-type compounds XIIMoO4 and XIIWO4. Spectrochim Acta A. 1972;28(11):2029–36.

Khanna RK, Lippincott ER. Infrared spectra of some scheelite structures. Spectrochim Acta A. 1968;24:905–8.

Hanuza J, Macalik L. Polarized i.r. and Raman spectra of orthorhombic KLn(MoO4)2 crystals (Ln = Y, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, Lu). Spectrochim Acta. 1982;38(1):61–72.

Hanuza J, Mączka M, van der Maas JH. Polarized IR and Raman spectra of tetragonal NaBi(WO4)2, NaBi(MoO4)2 and LiBi(MoO4)2 single crystals with scheelite structure. J Mol Struct. 1995;348:349–52.

Godlewska P, Tomaszewicz E, Macalik L, Hanuza J, Ptak M, Tomaszewski PE, Ropuszyńska-Robak P. Structure and vibrational properties of scheelite type Cd0.25RE0.5⌷0.25MoO4 solid solutions where ⌷ is the cationic vacancy and RE = Sm–Dy. J Mol Struct. 2013;1037:332–7.

Godlewska P, Tomaszewicz E, Macalik L, Hanuza J, Ptak M, Tomaszewski PE, Mączka M, Ropuszyńksa-Robak P. Correlation between the structural and spectroscopic parameters for Cd1−3xGd2x⌷xMoO4 solid solutions where ⌷ denotes cationic vacancies. Mater Chem Phys. 2013;139(2–3):890–6.

Kubelka P, Munk F. Ein Beitrag zur Optic der Farbanstriche. Z Tech Phys. 1931;12:593–601.

Urbanowicz P, Piątkowska M, Sawicki B, Groń T, Kukuła Z, Tomaszewicz E. Dielectric properties of RE2W2O9 (RE = Pr, Sm–Gd) ceramics. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2015;35(15):4189–93.

Franco A Jr, Pessoni HV. Optical band-gap and dielectric behavior in Ho—doped ZnO nanoparticles. Mater Lett. 2016;180:305–8.

Hone FG, Ampong FK, Abza T, Nkrumah I, Paal M, Nkum RK, Boakye F. The effect of deposition time on the structural, morphological and optical band gap of lead selenide thin films synthesized by chemical bath deposition method. Mater Lett. 2015;155:58–61.

Si S, Deng H, Zhou W, Wang T, Yang P, Chu J. Modified structure and optical band-gap in perovskite ferroelectric (1−x)KNbO3–xBaCo1/3Nb2/3O3 ceramics. Ceram Int. 2018;44(12):14638–44.

Lee HJ, Lee JA, Lee JH, Heo YW, Kim JJ, Park SK, Limb J. Optical band gap modulation by Mg-doping in In2O3(ZnO)3 ceramics. Ceram Int. 2012;38:6693–7.

Tauc J, Grigorovici R, Vancu A. Optical properties and electronic structures of amorphous germanium. Phys Status Solidi. 1996;15:627–37.

Tauc J, Menth A. States in the gap. J Non-Cryst Solids. 1972;8–10:569–85.

Lacomba-Perales R, Ruiz-Fuertes J, Errandonea D, Martinez-Garcia D, Segura A. Optical absorption of divalent metal tungstates: correlation between the band-gap energy and the cation ionic radius. EPL. 2008;83:37002.

Pontes FM, Maurera MAMA, Souza AG, Longo E, Leite ER, Magnani R, Machado MAC, Pizani PS, Varela JA. Preparation, structural and optical characterization of BaWO4 and PbWO4 thin films prepared by a chemical route. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2003;23(16):3001–7.

Zhang Y, Holzwarth NAW, Williams RT. Electronic band structure of the scheelite materials CaMoO4, CaWO4, PbMoO4, and PbWO4. Phys Rev B. 1998;57(20):12738–50.

Maurera MAMA, Souza AG, Soledade LAB, Pontes FM, Longo E, Leite ER, Varela JA. Microstructural and optical characterization of CaWO4 and SrWO4 thin films prepared by a chemical solution method. Mater Lett. 2004;58(5):727–32.

Singh BP, Parchur AK, Ningthoujam RS, Ansan AA, Singh P, Rai SB. Enhanced photoluminescence in CaMoO4: Eu3+ by Gd3+ co-doping. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:4779–89.

Mombourquette MJ, Weil JA, McGavin DG. EPR–NMR user’s manual. Saskatoon: Department of Chemistry University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon; 1999.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Karolewicz, M., Fuks, H. & Tomaszewicz, E. Synthesis and thermal, optical and magnetic properties of new Mn2+-doped and Eu3+-co-doped scheelites. J Therm Anal Calorim 138, 2219–2231 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08323-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08323-4