Abstract

Diphenyl sulfide was oxidized to sulfoxide and sulfone over V-doped TiO2 using a 30% solution of H2O2. The TiO2 samples with different intended content of vanadium (0.02, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.18 mass%) were prepared by incipient wetness impregnation. Physicochemical properties of the V-doped TiO2 were characterized by chemical analysis (ICP-OES), X-ray diffraction (XRD/in situ HT-XRD), UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectrometry (UV–Vis DRS), N2-sorption measurements, electron paramagnetic resonance and cyclic voltammetry. Both vanadium oxide loading and calcination temperature influenced the structure of the V-TiO2 samples. Vanadium species deposited on TiO2 decreased temperatures required for anatase to rutile phase transformation. The V-TiO2 samples were found to be efficient catalysts for oxidation of sulfides to sulfones. The sample with the lowest vanadium content (0.02VTiO2) presented among the studied catalysts the best catalytic properties with respect to high conversion of diphenyl sulfide to diphenyl sulfonate. An increase in vanadium loading resulted in decrease in catalytic activity of the samples. Also non-modified TiO2 presented significantly lower catalytic activity in comparison with 0.02VTiO2. This interesting effect was related to the formation of highly dispersed vanadium species catalytically active in Ph2S oxidation in the case of the samples with lower V-content. An increase in vanadium loading results in the formation of more aggregated V-species inactive, or less active, in the process of diphenyl sulfide oxidation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The interest in organic sulfoxides and sulfones production continuously increases due to their importance as synthetic intermediates for production of a broad range of chemically and biologically active substances, which can be used as therapeutic agents in many ailments including: antiulcer (proton-pump inhibitor) [1], antibacterial, antifungal, antiatherosclerotic [2], antihypertensive [3] and cardiotonic agents [4], as well as psychotronics [5] and vasodilators [6]. Many various oxidants (e.g., KMnO4, HNO3, RuO4) have been used for sulfide oxidation, but most of them are not suitable as catalysts to a large-scale operation for several reasons [7]. Most of them are characterized by high costs of production, low content of effective oxygen and formation unfavorable co-products during oxidation process [8, 9].

Among various methods of organic sulfoxides and sulfones synthesis direct catalytic oxidation of sulfides using H2O2 as oxidizing agent seems to be one of the most promising [7]. Hydrogen peroxide is not only effective oxidant, but also environmental-friendly because does not result in the formation of any harmful or toxic by-products. (Only water is formed as by-product of H2O2 decomposition.) Moreover, an aqueous solution of H2O2 is more effective from many other oxidants because of high content of active oxygen (about 47%) [9] and relatively low cost of its production [10] as well as safety in storage and operation. Hydrogen peroxide due to above-mentioned properties is often called as green oxidant. Moreover, H2O2 is very promising as oxidant in liquid-phase reactions because of its high solubility in water and various organic solvents [11]. The selective oxidation of organic sulfides to sulfoxides or sulfones using hydrogen peroxide as an oxidant needs effective catalysts. There is still discussion related to the role of catalysts and reaction mechanisms [9]. One of the most accepted mechanisms includes activation of hydrogen peroxide by electrophilic catalysts and its subsequent reaction with organic sulfides resulting in oxidized products [12]. Recently, many various transition metal (Ti, Fe, Mo, V, W, Mn, Re, Ru) compounds have been studied as potential catalysts for Ph2S conversion [13, 14].

Titanium dioxide is often used as catalyst or catalytic support due to its high chemical stability, low toxicity and relatively low cost [15, 16]. TiO2-supported vanadium oxides are extensively studied as effective and selective catalysts of organic compounds conversion [17,18,19]. For example V-doped TiO2 was studied as catalysts for selective oxidation of ethanol [20], degradation of aldehyde [21] or photo-oxidation of methane in air [22]. Moreover, V2O5–TiO2 oxide system is used as catalysts for the selective reduction of NOx to N2 by ammonia in flue gases emitted by power station and diesel cars [23]. Moreover, Ti-modified zeolites and mesoporous silica materials were tested as catalysts of the sulfoxidation reactions of aromatic sulfur compounds with hydrogen peroxide [24]. High catalytic activity of Ti-BEA and Ti-HSM was reported. On the other hand, Chica et al. [25] studied oxidative desulfurization of various organic S-containing compounds (thiophene, 2-methylthiophene, benzothiophene, 2-methylbenzothiophene, dibenzothiophene, 4-methyldibenzothiophene and 4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene) with tert-butyl hydroperoxide, as an oxidizing agent, on different metal-containing molecular sieves. It was shown that high catalytic efficiency of Ti-MCM-41 in the studied processes was related to a relatively high internal diffusion rate of reactants inside silica pores as well as the resistance of Ti species incorporated into silica wall to leaching.

In the presented studies, vanadium-doped commercial TiO2 (P25) was tested as catalyst for oxidation of sulfides to sulfoxides and sulfones by H2O2.

Experimental

Materials

The following chemicals were used in the studies: titanium (IV) oxide (Aeroxide P25, > 99.5%, Acros Organics), ammonium metavanadate (100%, Merck Millipore), acetonitrile (99.8%, Aldrich), bromobenzene (> 99.5%, Aldrich), diphenyl sulfide (98%, Aldrich) and hydrogen peroxide (30%, POCH).

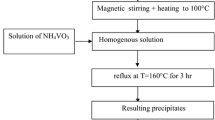

Catalyst preparation

Titania-supported vanadium catalysts were prepared by incipient wetness impregnation. The samples of the intended vanadium content of 0.02, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.18 mass% were obtained by soaking of the commercial titanium dioxide powder (P25) with an aqueous solution of ammonium metavanadate of suitable concentrations. The volume of the solutions used for impregnation was equal to water sorption capacity of P25. Then, the samples were dried overnight and finally calcined at 550 °C for 6 h (an increase of temperature from room temperature to 550 °C with the rate of 1 °C min−1 and then isothermal calcinations step at 550 °C for 6 h).

Catalysts characterization

The vanadium content in the samples was analyzed by ICP-OES method. Using Milestone mineralizer, 100 mg of the sample was dissolved in a mixture of 8 cm3 HCl (30%), 2 cm3 HNO3 (67%) and 1 cm3 HF (50%) at 190 °C. The obtained solution was analyzed with respect to V-content using ICP-OES instrument (iCAP 7400, Thermo Science).

The phases composition, crystal size and strain effects of the samples were studied by X-ray diffraction method (XRD) using a Bruker D2 diffractometer. The measurements were taken using CuKα radiation in the 2-theta range of 2–80° with a step of 0.02°. Moreover, the in situ high-temperature XRD (HT-XRD) measurements were taken in the temperature range of 25–900 °C in air atmosphere using a PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer (CuKα1/2, 1.54060Å). HT-XRD method was used to study the in situ phase changes as well as dynamics of crystal size changes and strain effects. Refinement of the anatase/rutile content was performed with the use of MAUD software for Rietveld analysis based on RITA/RISTA algorithms [26].

Textural parameters of the samples were determined by N2 adsorption at − 196 °C using a 3Flex (Micromeritics) automated gas adsorption system. Prior to the measurement, the samples were outgassed under vacuum at 350 °C for 24 h.

The form and aggregation of vanadium species deposited on TiO2 were analyzed by using UV–Vis DR spectroscopy. The measurements were taken on an Evolution 600 (Thermo) spectrophotometer in the range of 190–900 nm with a resolution of 4 nm.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of the studied samples were recorded at 25 °C using an ELEXSYS 500 Bruker spectrometer (Xband = 9.5 GHz) with the following parameters: magnetic field in the range of 2000 G, modulation amplitude around 3 G and 10 mW of power.

Cyclic voltammograms of the calcined samples were recorded in a three-electrode cell using a graphite paste electrode as the working electrode, platinum coil as the auxiliary electrode and Ag|AgCl as the reference electrode. Composite paste was prepared by mixing synthetic graphite (100–150 mg) with Nujol (0.05 cm3) and a small amount of the sample (0.005–0.010 g). The measurements were taken in acetate buffer (pH 4.0) as electrolyte at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1. Before experiment, the solutions were pretreated with argon to keep oxygen-free atmosphere during the measurement.

Catalytic studies

The samples of vanadium-doped TiO2 were tested as catalysts for oxidation of diphenyl sulfide (Ph2S) to diphenyl sulfoxide (Ph2SO) and sulfone (Ph2SO2) using hydrogen peroxide as an oxidation agent. The reaction was performed in 100-mL round-bottom flask equipped with a stirrer, dropping funnel and thermometer. The reaction mixture consisted of 2 mL (0.4 mmol) of diphenyl sulfide, 20 mL of acetonitrile used as a solvent, 10 μL (0.1 mmol) of bromobenzene used as internal standard and 25 mg of catalyst. The obtained mixture was stirred (1000 rpm) at 25 °C for 10 min, and then, 60 μL (2 mmol) of 30% hydrogen peroxide was added. In order to avoid photocatalytic reactions, the catalytic runs were performed in the dark. The progress of the reaction was monitored by analysis of the reaction mixture by HPLC method, using a mixture of acetonitrile/water with the volume ratio of 80:20 as an eluent. The samples of the reaction mixture were taken in regular intervals, filtered using 0.22-μm nylon membrane filter and analyzed by PerkinElmer Flexar chromatograph equipped with a COL-Analytical C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 μm pore size). The column was maintained at 25 °C throughout analysis, and UV detector was set at 254 nm.

The leaching of vanadium species from P25 was studied for the selected catalysts by chemical analysis of the reaction solution after separation from the solid catalyst by using ICP-OES method (iCAP 7400, Thermo Science). Moreover, in order to check the catalytic activity of V-species leached from the solid catalysts, into the solution separated after catalytic test the fresh reactants (H2O2 and Ph2S) were added and catalytic test was performed for the next 4 h.

Results and discussion

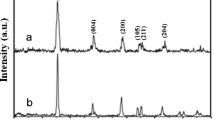

Phase composition of the samples was analyzed by XRD method. Diffractograms recorded for commercial TiO2 (P25) and its modifications with vanadium are presented in Fig. 1. It should be mentioned that all these diffractograms were recorded for the calcined samples, including also non-doped TiO2 (550 °C, 6 h). The reflections characteristic of two TiO2 phases—anatase (A) and rutile (R)—were identified in the studied samples [27, 28]. It should be noted that intensities of the reflections characteristic of rutile increased, while intensities of the reflections characteristic of anatase decreased after deposition of vanadium on the TiO2 support. It has to be remained that all the samples, including non-doped P25, were calcined at these same conditions. Thus, it seems that vanadium species deposited on TiO2 induced the phase transformation of anatase to rutile. Similar results were recently reported by Shao et al. [29], who suggested that this interesting effect is related to many factors, duration and temperature of calcination, synthesis method and type of dopant metal used. It is suggested that the anatase to rutile phase transformation is accelerated by incorporation of V4+ cations into vacant Ti4+ positions in TiO2 (anatase) [27, 30]. Such substitution is possible because of similar ionic radius of Ti4+ and V4+, which is 0.061 and 0.058 nm, respectively [30]. Moreover, this same valency of both cations results in electroneutrality of TiO2 anatase lattice. Consequently, V4+ incorporated into anatase lattice acts as initiation nuclei for anatase to rutile phase transformation [31]. In our studies, vanadium as V5+ ions was introduced into TiO2 with using a solution of NH4VO3. So the question is about possible reduction of V5+ to V4+ during the V-TiO2 sample synthesis. Recently, Kathun et al. [27] reported reduction of V5+ to V4+ deposited on TiO2 during calcination (450–750 °C) in air. The V5+:V4+ molar ratio, determined by authors, was 67:33 in the case of the sample containing 3 mol.% of vanadium and 45:55 for the sample containing 6 mol.% of vanadium. Moreover, similar effect of V5+ to V4+ reduction was observed by Banaras et al. [31] for the V-TiO2 catalysts during the process of methane oxidation.

In order to have more insight into anatase to rutile transformation in the presence of vanadium species an additional analyses, the Rietveld refinement and in situ HT-XRD studies, were done. The example of the Rietveld refinement of a theoretical line profile to the measured XRD profile is presented in Fig. 2, while the phase compositions of the samples determined by this method are compared in Table 1. Moreover, the average size of the anatase and rutile crystallites as well as the real vanadium content is included in this table. First of all, it should be mentioned that for all the samples the Rietveld refinement matches well with the observed diffraction peaks (similarly to the example presented in Fig. 2). Comparison of the results of the Rietveld refinements clearly shows that in a series of the samples calcined at 550 °C a significantly higher contribution of rutile phases is in the samples of TiO2 doped with vanadium (56–57%) in comparison with pure calcined TiO2 (13%). Moreover, it is shown that the content of introduced vanadium does not influence the anatase/rutile ratio in the samples. It should be also noted that doping of TiO2 with vanadium resulted in an increase of the size of anatase and rutile crystallites possibly during calcination process. This effect is more significant for rutile than for anatase. In Table 1, also textural parameters of the studied samples are compared. It can be seen that after introduction of vanadium the BET surface area of the samples increases from 9 to 27–39 m2 g−1. This effect is possibly related to partial opening of intercrystalline space associated with the anatase to rutile phase transformation and possibly also due to deposition of V-species on the surface of P25 particles in highly dispersed form. The BET surface area of the fresh (non-calcined) P25 sample was about 40 m2 g−1 and after calcination decreased to 9 m2 g−1, possibly as a result of sintering of the TiO2 crystallites. It should be also noted that the real content of vanadium deposited on the P25 surface is close to the intended values.

Example of Rietveld refinement plot for the 0.05VTiO2 sample. The observed patterns are expressed as solid blue line, and calculated point is represented by the dotted line. The difference between the experimental and the calculated intensities from the Rietveld refinement model is shown as red curve at the bottom of the diagram

In situ HT-XRD studies, performed for non-calcined pure TiO2 (P25) as well as its non-calcined modifications with various vanadium lodgings—0.02VTiO2 and 0.05VTiO2 are presented in Fig. 3. The measurements were taken at 25 °C and then from 100 to 900 °C with steps of 100 °C in air atmosphere with the linear temperature increase of 5 °C min−1. In the case of pure TiO2, a very significant increase in the intensities of the reflection characteristic of rutile and decrease in the intensities of the reflection attributed to anatase occurred between 700 and 800 °C. Such effect was also observed for the samples doped with vanadium (examples of the results for 0.02VTiO2 and 0.05VTiO2 are presented in Fig. 3) however, in these cases occurred at temperature lower by about 200 °C (between 500 and 600 °C). Thus, the results of in situ HT-XRD analysis of the non-calcined samples are in agreement with the results of XRD studies of the calcined samples and support the hypothesis that vanadium introduced into TiO2 (P25) catalyses thermally induced transformation of anatase to rutile. The significant difference in temperature of anatase to rutile phase transformations determined in XRD studies of the calcined samples (Fig. 1) and in situ HT-XRD measurements of the non-calcined samples (Fig. 3) could be explained by the relatively long duration (6 h) of the calcination process at 550 °C and relatively fast temperature increase (5 °C min−1) in the in situ HT-XRD studies of the non-calcined samples.

The nature of vanadium species deposited on TiO2 was studied by two spectroscopic methods—UV–Vis DR and EPR. Both vanadium and titanium species produce the UV–Vis adsorption bands in similar range, and therefore, the analysis of spectrum of the materials containing simultaneously both these elements is difficult. In order to overcome the problems with analysis of vanadium-doped TiO2 the original spectrum of calcined P25 was subtracted from the spectrum of the vanadium-modified P25. Figure 4 presents such differential spectra of the vanadium-doped TiO2 samples calcined at 550 °C and is related mainly to the presence of vanadium species. The spectra of the 0.02VTiO2 sample are characterized by the presence of only one intense adsorption band centered at 380 nm, which is probably superposition of two sub-bands. The first one, expected at about 350 nm, is related to rutile phases (different contribution of rutile in calcined P25 and in the samples doped with vanadium, see Table 1), while the second sub-band, expected at 400 nm, is assigned to the monomeric V5+ cations in tetrahedral coordination deposited on the TiO2 surface [31,32,33,34]. In spectra of the samples with higher vanadium loadings (0.05VTiO2, 0.1VTiO2 and 0.18VTiO2), apart from the band at 380 nm another band centered at about 450 nm can be found. The intensity of this band increases with an increase in vanadium loading. This band is related to octahedrally coordinated V5+ cations in small aggregates of V2O5 [29,30,31]. Thus, it could be suggested that small amounts of vanadium introduced to TiO2 are deposited in the form of the monomeric vanadium cations in tetrahedral coordination, while an increase in vanadium content results in its aggregation with the formation of V2O5. Banares et al. [31] suggested that highly dispersed vanadium species are stabilized by surface hydroxyl groups of titania. The content of such surface hydroxyl groups is larger for anatase than for rutile, and therefore, phase transformation from anatase to rutile accelerates the formation of aggregated V2O5 species, which are characterized by a weaker interaction with titania support.

The EPR spectra of pure and V-modified TiO2 are presented in Fig. 5. Compared with pure TiO2, the EPR spectrum of a series of the VTiO2 samples is significantly different. For undoped TiO2, the EPR spectra show small peaks at around 3500–3550 Gauss, which are assigned to the oxygen vacancy defects [35]. Such vacancy defects are possibly a result of the formation of Ti3+ ions with spectral slitting characteristic for hyperfine interactions with 47,48Ti nuclei [15]. In the case of V-doped TiO2, the peaks at around 3500–3550 Gauss are still present, indicating the paramagnetic features of the doped V-ions. The intensity of these signals increases with an increase in loading of vanadium introduced to the TiO2 support. In the case of the samples with higher V-content, the signals were broadened due to spin–spin interactions [15].

Moreover, the resolved hyperfine coupling, the same as for the undoped and vanadia-modified samples, shows that the dopant ions are dispersed in the crystal host. Tian et al. [36] reported that the eight-component hyperfine structure of the V-modified samples characterizes V4+ ions, which are incorporated into the crystal lattice of TiO2. (V5+ ions do not give signals in EPR.) The intensities of signals raised sharply, when vanadium loading increased from 0.05 to 0.1%, while the differences in signals of 0.02VTiO2 and 0.05VTiO2 as well as between signals of 0.1VTiO2 and 0.18VTiO2 are less significant. This effect could be explained by incorporation of V4+ cations into vacant positions in TiO2 lattice in the case of the samples with low vanadium loadings. With increasing content of vanadium, after filling of all available Ti vacancies by V4+ cations, vanadium is deposited in the form of extra-framework species, which at higher vanadium content, as it was shown by UV–Vis DRS studies (see Fig. 4), aggregate to small crystallites of V2O5. The results of EPR studies support presented earlier hypothesis related to the possible oxidation of V4+ to V5+ on the surface of TiO2 as well as show that V4+ can be incorporated into Ti vacancies in TiO2 lattice and act as initiation nuclei for anatase to rutile phase transformation.

The electrochemical properties of the selected samples were examined by cyclic voltammetry. Figure 6 shows the cyclic voltammograms obtained for calcined TiO2 and its modifications with vanadium—0.02VTiO2 and 0.18VTiO2. The main oxidation wave for the TiO2 sample is visible at Epa = 165 mV, while less intensive signals are located at 18, 370 and 617 mV. These signals are possibly related to the oxidation of Ti3+ cations present in the structure of TiO2. As it can be seen stabilization of such Ti3+ cations against oxidation to Ti4+ is different and possibly depends on their surroundings. The reduction wave can be observed at Epc = − 202 mV and could be assigned to the reduction of Ti4+ to Ti3+. The shape of the voltammogram profiles shows that the redox process is irreversible and oxidation dominates over reduction of the TiO2 sample.

Doping of TiO2 with very small amount of vanadium (0.02VTiO2) resulted in a shift of oxidation waves from 370 and 617 mV to 357 and 613 mV, respectively. This effect shows that doping of TiO2 with small amounts of vanadium results in easier oxidation of stable Ti3+ sites. Also reduction process proceeded easier for the 0.2VTiO2 sample in comparison with TiO2 (shift in the position of reduction wave from − 202 to − 191 mV). An increase in vanadium content to 0.18 mass% (0.18VTiO2) resulted in a shift of the main oxidative wave from 165 to 176 mV, what is possibly related to stronger stabilization of Ti3+ cations in TiO2. However, a shift of small signal from 18 to − 23 mV may suggest the existence of small fraction of easy-oxidizing sites.

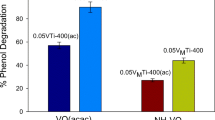

The samples of V-doped TiO2 were tested as catalysts for oxidation diphenyl sulfide (Ph2S) by H2O2. The results of the catalytic studies are presented in Fig. 7. The only detected products of Ph2S oxidation are diphenyl sulfoxide (Ph2SO) and diphenyl sulfone (Ph2SO2). It was reported by many authors that transformation of sulfides to sulfones proceeds via the sulfoxides intermediates [7, 9]. Thus, the progress in Ph2S oxidation can be determined by analysis of the substrate conversion as well as the progress in selectivity. The diphenyl sulfide oxidation in the presence of TiO2 resulted in the Ph2S conversion of about 77%, with 67% selectivity to Ph2SO2, after 4 h of the catalytic test. Introduction of small amounts of vanadium into TiO2, resulting in the 0.02VTiO2 sample, caused dramatic increase in the Ph2S conversion and selectivity to Ph2SO2. The nearly complete conversion of diphenyl sulfide in the reaction mixture with 100% selectivity to diphenyl sulfone was obtained after 3 h of the catalytic tests. Thus, it can be seen that modification of TiO2 with small amount of vanadium resulted in a very significant activation of the catalyst in oxidation process. An increase in vanadium content deposited on TiO2 resulted in gradual decrease in both Ph2S conversion and selectivity to Ph2SO2; however, these parameters are still higher than in the case of pure TiO2.

The leaching of active components deposited on the support is a common problem of the heterogeneous catalysis performed in a liquid phase. The analysis of the solutions after catalytic runs shows that this problem is also present in the case of our VTiO2 samples, especially those with higher vanadium loadings, which lost about 10% of active component. This effect was negligible for the samples with the lowest V-content. It was also shown, by additional test with the reaction mixture separated from the solid catalyst, that V-species leached from the catalyst were inactive in the process of Ph2S oxidation. Thus, the V-species leached from the solid catalyst are inactive in the studied process and interaction between such species and TiO2 support is necessary for their catalytic activation.

Thus, it could be concluded that introduction of small amounts of vanadium activated TiO2 much more effectively than deposition of larger amounts of vanadium. As it was shown by EPR and UV–Vis DRS studies disposition of small amounts of vanadium on TiO2 results in incorporation of V4+ cations in vacant Ti positions of titania as well as deposition of V5+ cations (or small oligomeric V-species) on the support surface. So, these forms of vanadium should be taken into account as potential catalytically active surface species. Banares et al. [31] reported that V4+ cations incorporated into Ti vacancies of rutile are very stable and do not have any tendency to be oxidized. Thus, no oxygen activation on such sites is expected. Probably the role of catalytically active species play V5+ cations deposited on the TiO2 surface, which can be relatively easy reduced to V4+ or even to V3+ and then re-oxidize to V5+ [30]. An increase in vanadium loading, as it was shown by UV–Vis DRS, results in aggregation of highly dispersed V-species to V2O5, which is probably inactive or less active than dispersed V5+ sites. Banares et al. [31] suggested that aggregated V2O5 is characterized by weaker interaction with titania support than highly dispersed V-species. Similarly to a leak of catalytic activity of V-species leached from the solid catalyst into solution, possibly also in the case of V2O5 only weak interaction with TiO2 support results in its lower catalytic activity in the studied process. Thus, it seems that both the form of V-species and their interaction with titania support determine catalytic properties of the VTiO2 samples.

Conclusions

The V-doped TiO2 samples, with different concentrations of vanadium, were obtained by wetness impregnation of the commercial titanium dioxide (P25) powder with aqueous solutions of ammonium metavanadate with suitable concentrations. Afterward, the obtained samples were characterized from the point of view of their structure, morphology, thermal behavior and catalytic properties in the process of Ph2S oxidation. Increasing V-content in TiO2 did not influence in major extent the structural, thermal and textural properties, but significantly change the catalytic activity. The catalytic tests of the TiO2 samples with different V-loading have shown that the introduction of small amounts of vanadium into titanium support (0.02VTiO2) resulted in more effective catalytic activation of titania—the nearly complete Ph2S conversion and 100% selectivity to final product. As the vanadium content increases, both Ph2S conversion and selectivity to Ph2SO2 slightly decrease. However, for all the V-modified samples the parameters characterizing the catalytic activity are still high.

It was suggested that V5+ cations dispersed on TiO2, which can be relatively easy reduced and re-oxidized, are the active sites of the studed catalytic reaction. On the other hand, V4+ cations, identified by EPR, are located in vacant Ti positions of TiO2 and are strongly stabilized against oxidation. Therefore cannot play a role of oxygen activation sites. An increase in vanadium loading results in aggregation of surface V-species to vanadium oxide (V2O5), which interact with titania significantly weaker than dispersed vanadium ions in the samples with low V-loadings and therefore catalysts with higher vanadium loadings presented lower catalytic activity. Thus, it could be concluded that both the form of V-species and their interaction with TiO2 support determine activity of the studied catalysts.

References

Lai SKC, Lam K, Chu KM, Wong BC, Hui WM, Hu WH, Lau GK, Wong WM, Yuen MF, Chan AO, Lai CL, Wong JN. Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long-term low-dose aspirin use. New Engl J Med. 2002;346:2033–8.

Sovova M, Sova P. Pharmaceutical significance of Allium sativum L. Antifungal effects. Ceska Slov Farm. 2003;52:82–7.

Kotelanski B, Grozmann RJ, Cohn JNC. Positive inotropic effect of oral esproquin in normal subjects. Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14:427–33.

Schmied R, Wang GX, Korth M. Intracellular Na+ activity and positive inotropic effect of sulmazole in guinea pig ventricular myocardium. Comparison with a cardioactive steroid. Circ Res. 1991;68:597–604.

Nieves AV, Lang AE. Treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in patient with Parkinson’s disease with modafinil. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2002;25:111–4.

Padmanabhan S, Lavin RC, Durant GJ. Asymmetric synthesis of a neuroprotective and orally active N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor ion-channel blocker, CNS 5788. Tetrahedron Asymmetr. 2000;11:3455–7.

Al-Maksoud W, Daniele S, Sorokin AB. Practical oxidation of sulphides to sulfones by H2O2 catalysed by titanium catalyst. Green Chem. 2008;10:447–51.

Prech J, Morris RE, Cejka J. Selective oxidation of bulky organic sulphides over layered titanosilicate catalysts. 2016;6:2775–86.

Sato K, Hyodo M, Aoki M, Zheng XQ, Noyori R. Oxidation of sulfides to sulfoxides and sulfones with 30% hydrogen peroxide under organic solvent- and halogen-free conditions. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:2469–76.

Jones CW. Applications of hydrogen peroxide and derivatives. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 1999.

Golchoubian H, Hosseinpoor F. Effective oxidation of sulfides to sulfoxides with hydrogen peroxide under transition-metal-free conditions. Molecules. 2007;12:304–11.

Vassell KA, Espenson JH. Oxidation of organic sulfides by electrophilically-activated hydrogen peroxide: the catalytic ability of methylrhenium trioxide. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:5491–8.

Kaczorowska K, Kolarska Z, Mitka K, Kowalski P. Oxidation of sulfides to sulfoxides. Part 2: oxidation by hydrogen peroxide. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:8315–27.

Bolm C, Bienewald F. Asymmetric sulfide oxidation with vanadium catalysts and H2O2. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 1996;34:2640–2.

Srinivas D, Holderich WF, Kujath S, Valkenberg MH, Raja T, Saikia L, Hinze R, Ramaswamy V. Active sites in vanadia/titania catalysts for selective aerial oxidation of β-picoline to nicotinic acid. J Catal. 2008;259:165–73.

Keshavarz M, Mojtaba Zebarjad S, Daneshmanesh H, Moghim MH. On the role of TiO2 nanoparticles on thermal behavior of flexible polyurethane foam sandwich panels. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;127:2037–48.

Busca G, Centi G, Marchetti L, Triifiro F. Chemical and spectroscopic study of the nature of a vanadium oxide monolayer supported on a high-surface-area TiO2 anatase. Langmuir. 1986;2:568–77.

Busca G, Marchetti L, Centi G, Triifiro F. Surface characterization of a grafted vanadium–titanium dioxide catalyst. J Chem Soc, Faraday Trans. 1985;81:1003–14.

Dyrek K, Serwicka E, Grzybowska B. ESR studies of the solid solutions of vanadium ions in TiO2. React Kinet Catal Lett. 1979;10:93–7.

Klosek S, Raftery D. Visible light driven V-doped TiO2 photocatalyst and its photooxidation of ethanol. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:2815–9.

Yang X, Cao Ch, Hohn K, Erickson L, Maghirang R, Hamal D, Klabunde K. Highly visible-light active C- and V-doped TiO2 for degradation of acetaldehyde. J Catal. 2007;252:296–302.

Yunarti RT, Lee M, Hwang YJ, Ha J-M. Transition metal-doped TiO2 nanowire catalysts for the oxidative coupling of methane. Catal Commun. 2014;50:54–8.

Bosh H, Janssen F. Catalytic reduction of nitrogen oxides. A review of the fundamentals and technology. Catal Today. 1988;2:369–79.

Hulea V, Fajula F, Bousquety J. Mild oxidation with H2O2 over Ti-Containing molecular sieves—a very efficient method for removing aromatic sulfur compounds from fuels. J Catal. 2001;198:179–86.

Chica A, Corma A, Dómine ME. Catalytic oxidative desulfurization (ODS) of diesel fuel on a continuous fixed-bed reactor. J Catal. 2006;242:299–308.

Ferrari M, Lutterotti L. Method for the simultaneous determination of anisotropic residual stresses and texture by X-ray diffraction. J Appl Phys. 1994;76:7246–55.

Khatun N, Rajput P, Bhattacharya D, Jha SN, Biring S, Sen S. Anatase to rutile phase transition promoted by vanadium substitution in TiO2: a structural, vibrational and optoelectronic study. Ceram Int. 2017;43:14128–34.

Kurajica S, Minga I, Mandic V, Matijasic G. Nanocrystalline anatase derived from modified alkoxide mesostructured gel. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;124:645–55.

Shao GN, Jeon S-J, Haider MS, Abbas N. Investigation of the influence of vanadium, iron and nickel dopants on the morphology, and crystal structure and photocatalytic properties of titanium dioxide based nanopowders. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;474:179–89.

Martinez-Huerta MV, Fierro JLG, Banares MA. Monitoring the states of vanadium oxide during the transformation of TiO2 anatase-to-rutile under reactive environments: H2 reduction and oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane. Catal Commun. 2009;11:15–9.

Banares MA, Alemany LJ, Jimenez MC, Larrubia MA, Delgado F, Granados ML, Martinez-Arias A, Blasco JM, Fierro JG. The role of vanadium oxide on the titania transformation under thermal treatments and surface vanadium states. J Solid State Chem. 1996;124:69–76.

Wang H, Qian W, Chen J, Wu Y, Xu X, Wang J, Kong Y. Spherical V-MCM-48: the synthesis, characterization and catalytic performance in styrene oxidation. RSC Adv. 2014;4:50832–9.

Vu AT, Nguyen QT, Bui THL, Tran MC, Dang TP, Tran TKH. Synthesis and characterization of TiO2 photocatalyst doped by transition metal ions (Fe3+, Cr3+ and V5+). Adv Nat Sci: Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2010;1:015009.

Chanquia CM, Canepa AL, Winkler EL, Rodriques-Castellon E, Casuscelli SG, Eimer GA. Directly synthesized V-containing BEA zeolite: acid-oxidation bifunctional catalyst enhancing C-alkylation selectivity in liquid-phase methylation of phenol. Mater Chem Phys. 2016;175:172–9.

Palkovska M, Slovak V, Subrt J, Bohacek J, Barbierikova Z, Brezova V, Fajgar R. Investigation of the thermal decomposition of a new titanium dioxide material—TA/MS and EPR study. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;125:1071–8.

Tian B, Li Ch, Gu F, Jiang H, Hu Y, Zhang J. Flame sprayed V-doped TiO2 nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation. Chem Eng J. 2009;151:220–7.

Acknowledgements

Part of the research was done with equipment purchased in the frame of European Regional Development Fund (Polish Innovation Economy Operational Program—contract no. POIG.02.01.00-12-023/08).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Radko, M., Kowalczyk, A., Bidzińska, E. et al. Titanium dioxide doped with vanadium as effective catalyst for selective oxidation of diphenyl sulfide to diphenyl sulfonate. J Therm Anal Calorim 132, 1471–1480 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-018-7119-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-018-7119-9