Abstract

A thermopile has been constructed for detecting heat of reaction during the individual steps taking place in the growth cycles of atomic layer deposition (ALD). The thermopile sensor consists of 64 junctions of thermocouple type K. It has successfully been applied to characterize ALD growth of Al2O3 from Al(CH3)3 (TMA) and H2O, and has furthermore been applied to explore energetics of ALD growth for the following combinations of precursors: TMA + O3, TMA + O2, TMA + hydroquinone, TiCl4 + H2O, and Zn(CH3CH2)2 + H2O. The thermopile clearly identifies exo/endothermal reaction steps, the effect of surface temperature on exposure to precursors from cold sources as well as variation in the flow of gases, and allows setting up of experiments where variations in precursors and pulsing parameters may provide mechanistic insight into the ALD growth. The sensor represents a new and complementary tool for in situ characterization of thin film growth by ALD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atomic layer deposition (ALD) is a thin-film-deposition technique utilizing alternating self-limiting gas-to-surface reactions. The film is formed by sequential pulsing of reactants separated by purging with inert gas between the precursor pulses to avoid gas-phase reactions [1–3]. Operated under ideal conditions, this process ensures saturation of all surfaces with precursor for each applied precursor pulse.

The mechanism behind ALD type of growth provides an ideal basis for studying reaction dynamics and kinetics of the underlying chemistry, benefiting from the alternating, self limiting, and repetitive operation. The reaction dynamics of ALD processes have previously been studied by various in situ techniques like: quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) [4–7], optical reflectometry [8–11], mass spectrometry [6, 7, 12], gravimetry [13], infrared absorption [14], reflection high-energy electron diffraction [15], ellipsometry [16], ion scattering [17], electronic resistivity [18], X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy [19], and now thermopile. The currently applied thermopile consists of a number of thermocouples connected in series where one collection of the thermo junctions is kept at a constant temperature, while the other is used as sensor. Thermopiles are currently being used as sensors in devices such as motion detectors, radiation detectors, heat sensors, and presently as a chemical reaction sensors for thin film depositions.

Typically, ALD type of depositions utilizes rather energetically favorable reactions, mostly being exothermic. It has until now not been possible to measure the release in thermal energy from deposition of one monolayer during ALD growth. By application of a thermopile as a measurement technique, the authors now demonstrate the feasibility to assess the relative magnitude in exothermal release in energy from the different subcycles of ALD growth.

Experimental

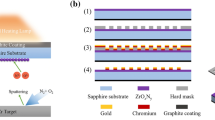

The thermopile is constructed according to the description in Fig. 1. The thermocouples used are of type-K (Chromel–Alumel) with a diameter of 0.2 mm, chosen due to easy availability and high-thermal sensitivity (41 μV/°C per thermocouple). The constructed thermopile consists of 64 thermocouples where one end is buried into the holes of a heat sink of brass. The holes were filled with heat resistant silicone to prevent reactions to take place at the reference junction, and also to electrically isolate the junctions from the heat-sink block.

The experiments were performed within an F-120 Sat reactor (ASM Microchemistry Ltd.) equipped with electrical feedthroughs. The signal from the thermopile was measured with an Agilent 34420A nanovoltmeter and recorded for post processing. The reactor pressure was maintained at ca. 2 mbar by employing a carrier-gas flow of 300 cm3 min−1 N2, supplied from a Nitrox 3001 nitrogen purifier with a purity of 99.9995% inert gas (N2 + Ar) according to specifications.

Deposition of Al2O3 by using Al(CH3)3 (TMA, Chemtura, 98%) and H2O (distilled) as reactants was chosen as process to test the sensor since this process is a well studied and further has a large exothermic signature [2, and references therein]. Depositions were made at a temperature of 186 °C and a pulsing sequence of 2 s TMA pulse, 1 s purge, 3 s H2O pulse, and finally 1 s purge. The flow of TMA and H2O was varied by using a Brooks 5-turn type needle valve. Both the TMA and H2O was kept at 20 °C by means of a Peltier cooling element, and both sources were delivered to the needle valve without use of any carrier gas.

Additional studies of thermopile performance and reaction energetics were performed using combinations of the precursors: TiCl4 (Fluka 99%), Zn(CH2CH3)2 (DEZ, diethylzinc, Chemtura, 98%), O3, and O2 (AGA, 99.999%). Ozone was produced by feeding pure O2 (AGA 99.999%) into an ozone generator (OT-020, OzoneTechnology) giving an O3 concentration of 15 vol.% according to specifications. The ozone gas was used at a flow of 500 cm3 min−1.

Results

The thermopile was used to investigate a series of campaigns, each consisting of five ALD deposition cycles, and where each campaign was separated by pauses of 1 min with only purge gas flowing past the sensor. For the various campaigns the flow of either TMA or H2O was varied by adjusting precursor inlet needle valves according to the scheme in Fig. 1. The very first campaign (not shown) was run with both valves fully open and thereby deposited a thin layer of Al2O3 that provides a representative surface termination for the proceeding campaigns. The signal from the thermopile was recorded under the entire deposition process and the data were post processed in order to remove a slowly undulating background. The results of the measured heat flow as function of pulse sequence and variations in the TMA and H2O flow are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

The evolution of heat as measured by a thermopile during alterations of TMA flow for the pulsing sequence: 5 s H2O, 2 s purge, 3 s TMA, 1 s purge. The valve for H2O was set at maximum (5-turns) and the valve for TMA was increased according to the numbers to the right of the graphs. The almost horizontal line represents the signal obtained when both precursors are closed

The evolution of heat as measured by a thermopile during alterations of H2O flow for the pulsing sequence: 5 s H2O, 2 s purge, 3 s TMA, 1 s purge. The valve for TMA was set at maximum (5-turns) and the valve for TMA was increased according to the numbers to the right of the graphs. The almost horizontal line represents the signal obtained when both precursors are closed

The reproducibility of the measurement technique was tested by comparing the signals recorded during different campaigns of the TMA + H2O process with both valves fully open. These campaigns were all separated by depositions of other types of materials (Fig. 4) without changing the experimental set-up. The complete test was done during one pump-down. The results prove the technique to be well-reproducible for a given parameter setting.

The evolution of heat during deposition of various materials as shown on right side of the figure. The pulse-purge scheme applied is: 3 s metal + 1 s purge + 4 s oxidant + 2 s purge. The data have been subjected to post processing to remove high- and low-frequency noise. TMA trimethylaluminium, DEZ diethylzinc, Hq hydroquinone

The thermopile was further applied for energetic characterization of depositions of other materials using the following combinations of precursors: TMA + O3, TMA + O2, TMA + hydroquinone, TiCl4 + H2O, and Zn(CH3CH2)2 + H2O. All pulsing sequences were 3 s metal source, 1 s purge, 4 s anion source, and finally 2 s purge. The valve settings on all sources were set at maximum for these experiments. All campaigns were separated by a campaign with TMA + H2O in order to produce a standard surface. The results are given in Fig. 4.

Discussions

The results from the thermopile measurements of the growth of Al2O3 in the TMA + H2O process confirm a notable exothermic reaction for both half reactions during the sequential pulsing. By inspection of the data in Figs. 2 and 3, several interesting observations are made.

By comparing the thermal signals obtained when one of the reactants is not delivered (closed valve) with the signals when both valves are closed, and also with the signal for overpulsing of reactants, it is evident that just supplying TMA and H2O to the surface have a cooling effect on the substrate. This is not surprising considering that the precursors are injected at a temperature of ca. 20 °C. The magnitude of this cooling effect appears to be larger for H2O than for TMA considering that it is able to bring the data set in Fig. 2 below its base line. This is reasonable considering the large heat capacity of H2O.

The measurements in Fig. 3 (maximum TMA pulse) were recorded after the campaign in Fig. 2 (maximum H2O pulse). By comparing the magnitude of the signals stemming from TMA and H2O-induced reactions in these different sets of data, it is evident that the magnitude of the signals from the TMA pulse and purges are nearly constant, whereas the magnitude of the energy release connected with the H2O pulse is nearly doubled in Fig. 3, i.e., for H2O reacting with an anticipated TMA saturated surface. If one anticipates that the exothermic signal observed for the TMA pulses correspond to a certain amount of reactive hydroxyl groups on the surface and methyl groups on TMA, one can conclude that there is a shift toward more liberation of heat when H2O is introduced for the latter series of campaigns where the films of Al2O3 has undoubtedly become thicker and covers the thermopile more completely. This could be interpreted as that the TMA reacts with fewer of its methyl groups when pulsed on a hydroxyl terminated surface as the film becomes thicker. The underlying reason for this observation is, however, unclear, but may stem from a chemical interplay with the surface of the thermocouple wire leading to differences in the surface chemistry as the film probably becomes more homogeneous.

The purging after a TMA pulse results in increased temperature, most probably due to removal of the cooling effect brought about by the excess TMA. It is interesting to note that the thermal effect on purging after the H2O pulse depends on the amount of introduced TMA. When H2O is pulsed alone, the subsequent purge results in increased temperature, probably also due to equilibration of the cooling effect by excess H2O, analogous to the TMA case above.

There are certain distinct differences in the growth of Al2O3 from TMA when H2O and O3 are used as the oxygen source (Fig. 4). For the reaction of TMA with the surface, the mechanism appears similar for both processes. However, when inspecting the reaction between O3 and the methyl-terminated surface, it is evident that the O3 reaction is much more rapid and more exothermic. This is reasonable considering that the flux of O3 is much larger than that of H2O, and that the subsequent reaction between |–CH3 and O3 to form CO2 and H2O is highly exothermic. When O3 is replaced by O2, a quite similar pattern is found for the O2 pulses, although of much smaller magnitude. However, almost no reaction is notable for TMA pulses, which is consistent with the fact that this system is not practical for film growth.

When water is replaced by hydroquinone, a pattern very similar to the TMA + H2O process is observed, although with a magnitude of the thermal effects reduced by a factor of three. Hydroquinone can replace water in a number of reactions with the result of forming organic–inorganic hybrid materials with much higher growth rates as their inorganic counterpart when using water [20]. The increased growth rate is due to the increased size of the hydroquinone, as compared with water, but this can also reduce the number of active sites on the surface for each reaction cycle. This latter effect can be observed using the thermopile in the sense that the thermal output is decreased accordingly, and can thus provide some hints on the relative surface occupation of the hydroquinone as compared to water. Even though, the time evolutions of the signal of the TMA reaction, as well as the relative magnitude of the signals from the half-reactions are quite identical.

For the growth of TiO2 from TiCl4 and H2O, the exothermic reaction appears comparable to that of H2O pulsed on to a TMA-terminated surface. The heat evolved during introduction of TiCl4 to the hydroxylated surface is, however, very small. When water is replaced by hydroquinone, almost no reaction is detectable by the thermopile even though the process results in growth rates much larger than when water is used.

When ZnO is grown from DEZ and H2O, just a minute exothermic reaction is seen after the introduction of DEZ on the hydroxylated surface. After the initial reaction the surface is effectively cooled by the excess DEZ, amounting to several mK. However, the effective reduction in surface temperature below its equilibrium value defined by the set-up, is counteracted already at the subsequent purging. The following introduction of H2O to the ethylated surface results furthermore in an exothermic reaction.

Figures 2 and 3 show that the process gases, H2O and TMA, reduce the temperature of the surface when introduced, which is expected since they both are introduced from precursors lines held at room temperature. The reduction in base line of the temperature may range up to 0.04–0.07 mV. For comparison the largest heat evolutions presented in Fig. 2 for a single cycle are ca. 0.02 mV. The authors have not been able to derive one accurate conversion factor from the thermopile signal into the temperature scale. However, an estimate is provided by considering the 64 type-K thermocouples with a sensitivity of 41 μV/K giving an overall sensitivity of 2.6 mV/K. This would suggest a variation in temperature of ca. 7.6 mK for a deposition cycle, and probably some 15–25 mK during the first cycles of deposition. It should be kept in mind that the current construction of the thermopile contains several sources for possible systematic errors, such as thermal transport through the wires, the heat capacity of the wires and the sensor in overall, as well as the competing cooling effects of the flushing gases and the precursor itself. However, all these effects work toward reducing the temperature. This indicates that the actual increase in temperature of the topmost surface could be larger than estimated.

A theoretical response of the TMA + H2O process can be constructed considering that the present thermopile is constructed of K-type thermocouples, Chromel and Alumel, with respective heat capacities of 0.521 and 0.526 J/gK and densities of 8.5 and 8.6 g/cm3. By combining this with the overall sensitivity of the present thermopile of 2.62 mV/K, the heat response of this thermopile can be calculated to be 36.4 mV/J for its complete active area or specifically 113 μV/Jmm2.

The heat evolved for the complete TMA + H2O reaction:

can be calculated based on heat of formation of the individual compounds [21, 22] to be −1206 kJ/mol. The overall ALD growth rate for this process has been reported to be ca. 0.09 nm/cycle [2], which gives an average density of reaction sites containing Al of ca. 4.24 Al/nm2 when taking basis in a unit cell volume of Al2O3 of 0.2547 nm3 [23] and six formula units in the unit cell.

With this as basis, the heat evolved per surface area should be 4.24 μJ/mm2 and the signal recorded for the complete reaction for this thermopile should be 50 mV, while it was ca. 20 mV for the half reaction of H2O with the methyl terminated surface (Fig. 2), and ca. 5 mV for the half reaction of TMA with the hydroxylated surface (Fig. 3).

These variations in temperature should be of relevance for evaluation of measurements by in situ QCM analysis for assessing mass differences during depositions. The QCM technique is sensitive toward changes in temperature above some 150 °C [24]. At 200 and 300 °C it is estimated that the sensitivity toward temperature is some 70 and 240 Hz/K, respectively [24]. When combining the dimensions of a typical 6 MHz crystal with the theoretical heat evolution for the TMA + H2O process of 4.24 μJ/mm2, one obtains a variation in temperature of 0.015 K for a complete cycle. This result in signal responses of 1.0 and 3.5 Hz for measurements performed at 200 and 300 °C, respectively. The response during QCM measurements varies greatly between different sensor constructions and material processes. It may range from a few Hz to above 100 Hz/cycle. The in-house measurements of the TMA + H2O process results in responses of ca. 25 Hz/cycle. In conclusion, the evolution of heat may be responsible for 5–15% of this QCM signal. The present thermopile detected only about half of the expected signal from the exothermic reactions. However, as Figs. 2 and 3 reveals, the sensor is also influenced by other thermal effects which are significantly large in magnitude.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the capabilities of a thermopile for characterization of heat evolved during individual reaction steps during the growth cycles in the ALD process. Using the thermopile, the authors have characterized the heat signatures of the growth of Al2O3 from TMA and H2O, as well for thin films grown by the precursor combinations: TMA + O3, TMA + O2, TMA + hydroquinone, TiCl4 + H2O, and Zn(CH3CH2)2 + H2O. The thermopile represents a new tool that shed light on the energetics of reactions taking place during thin film growth by ALD.

References

Ritala M, Leskelä M. In: Nalwa HS, editor. Handbook of thin film materials, vol. 1. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. p. 103–59.

Puurunen RL. Surface chemistry of atomic layer deposition: a case study for the trimethylaluminum/water process. J Appl Phys. 2005;97:121301/1–52.

Pakkala A, Putkonen M. In: Bunshah RF, editor. Handbook of deposition technologies for films and coatings, vol. 1. 2nd ed. Burlington: Elsevier; 2010. p. 364–91.

Rocklein MN, George SM. Temperature-induced apparent mass changes observed during quartz crystal microbalance measurements of atomic layer deposition. Anal Chem. 2003;75:4975–82.

Elam JW, Groner MD, George SM. Viscous flow reactor with quartz crystal microbalance for thin film growth by atomic layer deposition. Rev Sci Instrum. 2002;73:2981–7.

Matero R, Rahtu A, Ritala M. In situ quadrupole mass spectrometry and quartz crystal microbalance studies on the atomic layer deposition of titanium dioxide from titanium tetrachloride and water. Chem Mater. 2001;13:4506–11.

Rahtu A, Ritala M. Integration of a quadrupole mass spectrometer and a quartz crystal microbalance for in situ characterization of atomic layer deposition processes in flow type reactors. Proc Electrochem Soc. 2000;2000–13:105–11.

Bellandi E, Crivelli B, Elbaz A, Alessandri M, Boher P, Defranoux C. Optical characterisation of high-κ materials deposited by ALCVD. Proc Electrochem Soc. 2003;2003–3:316–21.

Rosental A, Adamson P, Gerst A, Niilisk A. Monitoring of atomic layer deposition by incremental dielectric reflection. Appl Surf Sci. 1996;107:178–83.

Nishi K, Usui A, Sakaki H. In situ optical characterization of gallium arsenide and indium phosphide surfaces during chloride atomic layer epitaxy. Thin Solid Films. 1993;225(1–2):47–52.

Kobayashi N, Kobayashi Y. In situ monitoring and control of atomic layer epitaxy by surface photo-absorption. Thin Solid Films. 1993;225(1–2):32–9.

Henn-Lecordier L, Lei W, Anderle M, Rubloff GW. Real-time sensing and metrology for atomic layer deposition processes and manufacturing. J Vac Sci Technol B. 2007;25:130–9.

Koukitu A, Kumagai T, Taki T, Seki H. Halogen-transport atomic-layer epitaxy of cubic GaN monitored by in situ gravimetric method. Jpn J Appl Phys. 1999;38:4980–2.

Dillon AC, Ott AW, Way JD, George SM. Surface chemistry of Al2O3 deposition using Al(CH3)3 and H2O in a binary reaction sequence. Surf Sci. 1995;322:230–42.

Bankras RG, Holleman J, Schmitz J. In situ RHEED of atomic layer deposition. Proc Electrochem Soc. 2005;2005–09:555–62.

Langereis E, Heil SBS, van de Sanden MCM, Kessels WMM. In situ spectroscopic ellipsometry study on the growth of ultrathin TiN films by plasma-assisted atomic layer deposition. J Appl Phys. 2006;100:023534/1–10.

Chang HS, Hwang H, Cho M-H, Moon DW. Investigation of the initial stage of growth of HfO2 films on Si(100) grown by atomic-layer deposition using in situ medium energy ion scattering. Appl Phys Lett. 2005;86:031906/1–3.

Schuisky M, Elam JW, George SM. In situ resistivity measurements during the atomic layer deposition of ZnO and W thin films. Appl Phys Lett. 2002;81:180–2.

Kodama K, Ozeki M, Sakuma Y, Mochizuki K, Ohtsuka N. In situ X-ray photoemission spectroscopy for atomic layer epitaxy of indium phosphide and gallium arsenide. J Cryst Growth. 1990;99:535–9.

Nilsen O, KlepperK B, Nielsen HØ, Fjellvåg H. Deposition of organic-inorganic hybrid materials by atomic layer deposition. ECS Trans. 2008;16:3–15.

Dean, John A. Lange’s handbook of chemistry. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1979. p. 94–994.

Kurt WE, Alan TC. Reaction of group III metal alkyls in gas phase. VI. The addition of ethylene to trimethylaluminium. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:1810–5.

Thompson P, Cox DE, Hastings JB. Rietveld refinement of Debye-Scherrer synchrotron X-ray data from Al2O3. J Appl Crystallogr. 1987;20:79–83.

Elam JW, Pellin MJ. GaPO4 sensors for gravimetric monitoring during atomic layer deposition at high temperatures. Anal Chem. 2005;77:3531–5.

Acknowledgements

This study has received financial support from FUNMAT@UiO/SMN.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nilsen, O., Fjellvåg, H. Measuring the heat evolved from individual reaction steps in atomic layer deposition. J Therm Anal Calorim 105, 33–37 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-011-1630-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-011-1630-6