Abstract

A curriculum innovation requires new learning material for students and a preparation program for teachers, in which teacher learning is a key ingredient. In this paper we describe how three experienced teachers, involved in the development and subsequent classroom enactment of student learning material for context-based chemistry education, professionalized. For data collection a questionnaire, three interviews and discussion transcripts were used. Our results show that: (a) teachers, cooperating in a network under supervision of an expert, can develop innovative learning material; (b) the development of learning material can be seen as a powerful program to prepare teachers for an innovation; and (c) teachers’ knowledge increased in all five pedagogical content knowledge domains during the development and class enactment phases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A rather recent curriculum change in chemistry in several countries is the development and introduction of context-based education. In this type of education, appealing contexts for students are used as a starting point for learning, not merely to demonstrate science applications in daily life at the end of a topic. Context-based science education adopted the view that science content is negotiated within realities, evolving and flexible (Bencze and Hodson 1999), and not just a set of rules and principles to be memorized. Specific forms of context-based approaches were developed in chemistry curriculum renewal schemes in, for example, Chemistry in the Community in the United States (Schwartz 2006), Salters Advanced Chemistry in the United Kingdom (Bennett and Lubben 2006) and Chemie im Kontext in Germany (Parchmann et al. 2006). A similar context-based curriculum change was initiated in the Netherlands (Driessen and Meinema 2003), under the name “context-concept” approach. This reform is seen as a complete renewal of the chemistry high-school curriculum, touching upon the educational goals, the subject content and the pedagogy. Successful implementation of such a curriculum requires attention for students and teachers. For students, new learning material has to be developed, a process often performed by professional developers. Teachers need to understand and be prepared and equipped for this context-based education, as they are the ones to enact it in their classes. Development of student learning material and teacher preparation can be combined through the involvement of teachers in the development of the material. This study is about professional growth of three teachers during the development and subsequent class enactment of student learning material for a context-based chemistry curriculum. In the following sections we will first look at teacher learning to prepare for a reform, next at the teacher as developer of student learning material, and finally describe the context in which this study is embedded.

Teacher Learning in Preparation of a Reform

What teachers do in class is largely influenced by their knowledge and beliefs about teaching and learning (Sanders 1993; Walberg 1991). In turn, experiences in class influence teachers’ knowledge and beliefs (Veal 2004). In their daily work teachers use their practical knowledge (Barnett and Hodson 2001) of which pedagogical content knowledge, PCK, is an essential part. Shulman (1987) initially described PCK as knowledge for teaching. Since Shulman, PCK has been studied by many researchers and been interpreted in different ways (Cochran et al. 1993; Gess-Newsome 1999). Park and Oliver (2008) defined PCK as “teachers’ understanding and enactment of how to help a group of students understand specific subject matter…”, and it is therefore shaped in school practices through reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. PCK can be characterized comprising five components: (a) knowledge of science curricula, (b) knowledge of students’ understanding of science, (c) knowledge of assessment, (d) knowledge of instructional strategies, and (e) orientation to teaching subject matter (Abell 2008; Grossman 1990; Magnusson et al. 1999). An expert teacher has well formed PCK for all topics taught, developed and shaped in teaching practice through reflection, active processing and integration of its components (Clermont et al. 1994; Van Driel et al. 1998). Teachers’ beliefs act like a filter through which new knowledge is interpreted and integrated (Pajares 1992).

As teachers’ knowledge and beliefs greatly impact classroom practices, expanding and changing these must be a key ingredient in any educative reform (Pintó 2005). Different intervention programs to prepare teachers for a curriculum change have been described in literature. Some studies focused on inservice activities to train teachers for a renewal (Fullan 1998). In general, these activities were not effective. Therefore, Lumpe (2007) called on science educators to stop one-shot workshop models of professional development as teachers seldom put into practice in their classrooms what they had learned. Other studies let teachers experience the learning they wanted to engage their students in for themselves (Jeanpierre et al. 2005; Loucks-Horsley et al. 1998). These studies showed that deep science content and process knowledge plus opportunities for practice did help some teachers to take the renewal into their classes. Other scholars reported on the use of curriculum materials to support teacher learning for a renewal (Van den Akker 1988; Voogt 1993). It appeared from these studies that the use of material with detailed lesson descriptions and specific support for teacher thinking, can help implementation but is still insufficient with respect to the renewal intentions (Schneider et al. 2005). Furthermore, teacher characteristics such as knowledge, beliefs, and dispositions towards reflection, also limit the effectiveness of curriculum material used for teacher learning (Davis and Krajcik 2005). In all these intervention programs, the center-periphery model of curriculum development was used (Guskey 2000; Stronkhorst and van den Akker 2006) in which teachers are at best involved in the process of piloting curriculum material developed by others.

A complicating factor is that reform policies affecting teachers’ classrooms can give rise to emotions towards the reform (Schmidt and Datnow 2005), may elicit actions of resistance (Kelchtermans 2005), and might be threatening to teachers’ professional identities (Van Veen and Sleegers 2006). In the Dutch chemistry curriculum renewal scheme described in the next section, resistance and feelings of threat may arise, because the current chemistry teachers have not been educated to teach, nor have experience with, context-based chemistry (De Vos and Verdonk 1990). These aspects are addressed when teachers are engaged in the curriculum change process from the beginning, for example through participation in the development of student learning material (George and Lubben 2002; Tal et al. 2001).

Teacher as Developer of Learning Material

Dutch teachers consider the combination of teaching and developing curriculum material as valuable (Coenders et al. 2008). In their day-to-day work teachers experience how students learn and what fascinates them, and they can use this knowledge when they act as learning material developers.

Teachers’ beliefs regarding learning material need to be taken into account (Cotton 2006; Rousseau 2004), and this is provided for by placing teachers in the role of developers of learning material. When the learning material has to be innovative, developers need to be able to draw on external resources for new ideas. Clarke and Hollingsworth (2002) called these resources the External Domain in their interconnected model of teacher professional growth. Different kinds of external resources can be used. For example, someone with specific expertise can be consulted or included in a development team. Literature is another potential external source. Reflections on teaching experiences can also act as sources, internal for the reflective teacher personally, and external for other teachers. The idea behind the teacher-as-developer is that the design and development of learning material suitable for their own students can be considered as professional development for the teachers involved (Ball and Cohen 1996). It is supposed that this process creates ownership of the learning material, boosts confidence, and stimulates deliberate reflection on action (Valli 1992). Collaborative interactions in which teachers work together to examine and improve their practice, are powerful (Borko 2004). In this approach, teacher-developers do not need in-service programs before implementation, because they can immediately employ the material in their classes as the preparations for class enactment have taken place concurrently with the development of the learning material. Elements previously to be included in traditional inservice training programs (Joyce and Showers 1995), like explanation of the rationale and goals of the innovation, demonstration of vulnerable aspects, and practice with the material, can now become attention points and discourse themes throughout the process of developing learning material.

The Context of the Study

A committee, installed by the Dutch Ministry of Education, to investigate problems and shortcomings of the current chemistry curriculum (Van Koten et al. 2002) published recommendations for a new curriculum (Driessen and Meinema 2003). The major recommendations were: (a) the chemistry content should appeal to all students, not only those who want to pursue a career in chemistry; (b) contemporary chemistry and societal challenges should be included in the curriculum; and (c) the introduction of the context-concept approach in pedagogy. Teacher networks would be set up to develop the new student learning material. To avoid confusion, in the rest of this paper the term ‘teacher-developer’ will be used for those teachers who, in addition to performing normal teaching tasks in their own school, are involved in the development of student learning material in a network.

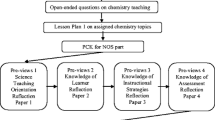

A teacher network consisted of three to five teacher-developers from different schools, plus a coach who acted as a chair and served as the liaison between the network and the national coordination. The schools employing the teacher-developers facilitated the development process by releasing these teacher-developers from part of their teaching tasks, and agreed to test the initial version of the learning material. The mission of the network was to develop and test student learning material, in the form of a complete module, in line with the national recommendations, in particular the context—concept approach. A complete module comprises of all texts, exercises and assignments, practical activities, and other student learning activities, ready for direct class use. A framework of the development process of a module is depicted in Fig. 1. In this development process two distinctive phases for teacher learning were distinguished: a writing phase and a class enactment phase. During the writing phase of the module, all texts, exercises and assignments, practical activities, and other learning activities were developed. After completion, the module was enacted in class and the resulting experiences were used to revise the module.

Networks received the following instructions: (1) The module has to be suitable for Form 3, the first year students (of about 15 years of age) take a chemistry course in secondary school. (2) The interaction between an interesting context for students and a number of chemistry concepts present in this context needs to be the central element (the context-concept approach). (3) The network bears responsibility for the selection of the context and of the concepts students have to learn. (4) Concepts should follow “naturally” from the context as was exemplified in the Salters materials (Campbell et al. 1994). Rigid following of syllabus objectives or of a subject content structure should be avoided. (5) The four stages used by Chemistry in Context in Germany (Parchmann et al. 2006) had to be applied in the module: (a) the teacher first introduces the context; (b) students are made curious and plan their investigations; (c) students carry these out and process the results; and (d) finally all knowledge is brought together. (6) The module should be appropriate for approximately 8–10 periods of 50 min each. Within these guidelines, a teacher network had freedom to decide on a context, on learning activities and materials, on pedagogy, and on assessment methods of student learning results. Process variables like the members’ task allocation within the network, the number of face-to-face meetings, and the communication between the meetings were also left to the discretion of a network. Several teacher networks were established throughout the country.

Aims of the Study

This study concerns the professional development of teachers: to what extend do the knowledge and beliefs of the teacher-developers change during the development and the subsequent class enactment of a new chemistry module? The following specific research questions were addressed: (1) What are the teacher-developers’ perceived goals of context-concept based chemistry education (a) before the development process (b) after the writing phase of the module, and (c) after class enactment of the module? (2) What did teacher-developers learn (a) during the writing phase (b) during the class enactment phase?

Method

A multiple case study design (Yin 2003) was used, because the purpose was to thoroughly investigate the changes each teacher-developer goes through. To address internal validity we employed different data collection instruments. This multi-method approach (Meijer et al. 2002) is inherently time consuming but teachers’ knowledge and beliefs system are complex (Pajares 1992), and developments in this system difficult to assess.

Participants

This particular network, which had a similar composition and operated like all the others, was chosen for purely practical reasons: the teachers were employed by three different schools not too far from the university of the researchers. The network consisted of three experienced chemistry teachers, all having a masters’ degree plus teaching qualification in chemistry, and more than 5 years of teaching experience. We will name these Pete, Lisa and Ed. A male coach employed by the teacher training department from a university was chair of the network. The coach, an experienced author of chemistry textbooks, contributed to the discussions by bringing in new ideas, alternative teaching approaches, literature, and he advised during the writing up phase. All teachers were currently teaching and participated on a voluntary base in this development process for which they received a reduction in teaching load of half a day per week from their school.

Instruments

Different instruments were used at various stages in the development process. Two instruments were used before the development activities in the network started: a questionnaire (A1) and an interview a few weeks later (A2). After the writing phase, each teacher-developer was interviewed (B), and once again after class enactment of the module (C). For each interview a semi-structured interview guide was used. Figure 2 depicts where the different instruments were employed in the process. In the appendix the instruments A1, A2, B and C are shown.

During the interviews more questions were posed than used for this article; they will be reported elsewhere. Questions of A1, A2, B, and C referring to the perceived goals of chemistry education were used to address research question 1 about the beliefs teacher-developers have with respect to the goals of chemistry education. To answer research question 2 on what teachers have learned, in both interview B and C teacher-developers were asked what they had learned. Some questions provided indirect information on research question 2. For example what the teacher-developers considered new aspects in the module in comparison to their “traditional” chemistry education, and why they considered this new. The different instruments in relation to the research questions are shown in Table 1.

Procedure

The complete development process lasted one school year. The first face-to-face meeting was held in September 2004, the last in June the following year. In total nine meetings took place, varying in time between 2–4 h. In between the meetings e-mail correspondence occurred.

The module was developed from scratch. A brainstorm session to identify potential contexts and concepts within these contexts initiated the beginning of the development process. Several themes were discussed in light of the main criterion that the context should be appealing to all students. At the end ‘Baking’ was selected, and the specific context became ‘Baking a cake’. The concepts emerging from this context were not new to the teacher-developers as they were part of the existing syllabus. However the way students were introduced to these concepts starting from the context was new. Network meeting transcripts show that after intensive discussions it was agreed that cooperative learning, including the use of students’ roles with specific tasks within the group, and the use of a group logbook, would be used. The envisaged advantage was that students could work more independently in cooperative groups and would require less teacher assistance. These could spend more time on organizational issues and on monitoring learning progress. Cooperative learning, using group roles and a logbook, was new to all three teacher-developers.

Analysis

All interviews, A2, B and C from each teacher-developer were first transcribed verbatim. In each transcript, passages that exemplify ideas related to the research questions were identified and highlighted. These characteristic phrases from each questionnaire were then tabulated in a created word table. The results for research question 1, related to beliefs on goals of chemistry education, are shown in Table 2. Analysis of the characteristic phrases with respect to teacher-developer learning, research question 2, resulted in two categories in which learning occurred: teaching methodology, and learning materials and chemistry content. Learning during the writing phase is reported in Table 3, during enactment in Table 4. To ensure the reliability of the data processing, a researcher, not previously involved in this research, was asked to perform two tests. The first one served to confirm the presence of each of the characteristic phrases in the transcribed interviews. A second to determine whether all sentences considered characteristic were indeed identified and tabulated. This resulted in first instance in 85% agreement. Disagreement occurred with two characteristic phrases not confirmed by the second researcher, who added also eight new ones. Parts not agreed upon were discussed and verified against the transcripts. The outcome of this process was that one characteristic phrase was changed and that seven were added to the original set.

Results

We will first describe relevant context for each of the three teacher-developers and then present the results to address the research questions.

Pete

At the start of the network Pete had neither experience with the development of student learning material, nor had he used contextualized material in his classes. His main reason to participate in this network was personal—he wanted to grow further as a teacher. He found it important to continuously professionalize as “the world constantly changes.” Pete used the module in two of his classes, but did make some minor changes to the material before class use, because he did not have sufficient time to enact the module as planned.

Lisa

Lisa had no experience with the development of learning materials for students of these levels, and had never used context-based materials. Her main reason for participation in this network was change. She wanted to get away from teacher-centered teaching and she sought to develop an alternative with colleagues. She slightly adapted the module before class use. At her school, two teachers not involved in the development process, wanted to use the module also in their classes and negotiated with Lisa about adaptations to be made in the module.

Ed

Ed had been involved in the development at national level of practical assignments for students, but had no experience in developing context-based materials. He had not previously used context-based materials. His main reason to join the development process was triggered by a discussion he had with a non-science colleague at school who had no idea how chemistry contributed to his life, something Ed considered an imperative goal for chemistry education. He used the module in his class, as did a colleague at his school not involved in the development. A few minor changes were made in the material before class use. Ed, being the advocate of a role-play to model a chemical reaction, had his students perform this role-play in class.

Perceived Goals

A summary of the data to answer these teacher-developers’ perceptions of the goals of chemistry education, research question 1, are presented in Table 2.

Pete’s initial goals of chemistry education were rather vague and general. According to Pete, the relevance of chemistry should be emphasized using news items from newspapers or magazines. Students also need to become enthusiastic for chemistry and have to realize that chemical concepts are close to their own life world. The following phrase, in which Pete talked about decomposition, a common chemistry concept, illustrates this: “Students need to be able to apply acquired concepts in a new context and should recognize decomposition during a barbeque”. Concrete contexts should be transferred into abstract concepts: “students have to consider what happens at molecular level during decomposition at the barbecue.”

During class enactment of the module, he experienced that students did not acquire concepts from a context automatically. This will require explicit attention both in the material and from the teacher in class. As another goal of context-based chemistry education, Pete now mentioned that students should be able to link acquired concepts. He noticed that students did not do this by themselves and he said: “Students need to learn this; it is a skill to discover structure in chemistry concepts.”

Before the development process started, Pete’s goals of chemistry education were general in nature, and in his view students would be able to pick up the concepts easily from a context. Class enactment showed that students did not automatically discover concepts, and did not learn how to link the concepts they acquired. In these aspects Pete’s goals evolved.

Lisa formulated the goals of chemistry education at the start of the development process in very general educational terms. For her, students should learn to appreciate chemistry and the role it plays in people’s life. She said: “students should develop the idea that one always deals with chemistry, and not perceive it as a weird and compulsory subject.”

After the writing phase she translated the goals in more concrete terms as is illustrated by the following phrases: “I hope that students can work independently and will enjoy what they do. They can work on own small research projects, for example to separate colors from sweets.” She also acknowledged cooperation within student groups as a specific goal, but this at the same time frightened her as she was concerned to lose control. Lisa was aware of the gender differences: “Students being more independent can do things they appreciate, but how girls experience it is to be seen, although the context ‘baking’ looks promising.”

Class enactment showed that students did not learn what was anticipated. The activities were carried out, but the students did not get the chemistry concepts clear. Lisa formulated this as follows: “Students became quite independent but did not always see what was meant. I think that this needs to be added, a kind of a summary of the concepts.” A bit later Lisa said: “Students hardly link concepts, also not previously learned concepts. Before this module students had learned a lot about safety in the lab, but did not link this to safety issues in this module.” Looking at the complete development process, Lisa’s beliefs about goals changed noticeably–from very general notions initially, to more pedagogic goals after the writing phase, to goals associated with learning at a conceptual level after class enactment.

Ed’s goals of chemistry education initially focused on meaningful chemistry and how chemistry positively contributes to people’s lives. He was quite outspoken in this as he formulated quite a number of broad goals. In the interview, Ed said that he wanted “students to learn more naturally in order to get more feeling and understanding from within towards the subject, which will create more ownership and sympathy.”

During the writing phase another goal emerged–the notion of differentiation and personal concept deduction. He said: “Students should be given the opportunity to develop the concepts themselves, I have some experience with it and it worked out well.” As the developed module was meant for the last term of the school year, Ed added as specific goal that students need to end the year pleasantly.

Finally, his classroom experiences strengthened the differentiation goals, and the concept development goals concretized as the students’ ability to transform concrete interaction with materials to an abstract level. Ed stated: “So this concrete, the interaction between the concrete and the abstract is extremely important.” In his view another goal would be to foster student’s confidence in the sense that they should experience being able to acquire knowledge themselves, something that can be elicited by starting from a concrete situation. Ed’s beliefs about the goals of chemistry education changed and matured during the complete development process.

Teacher-Developer Learning

The following section is devoted to what Pete, Lisa and Ed learned, research question 2. We will first present teacher learning during the writing phase, then in the class enactment phase.

Teacher Learning during the Writing Phase

Two categories of answers emerged: (a) about teaching methodology, and (b) about learning materials and chemistry content. A summary of the results is presented in Table 3.

Pete discovered cooperative learning as a methodology: “Specific attention for cooperative learning processes as such and the reflection that is explicitly incorporated is for me renewing.” A bit earlier Pete said: “I intend to use cooperative learning, including the group member roles and the logbook, and want to use the T-cards to teach cooperative skills.” This use of cooperative learning will enable him to move away from teacher centered classes: “Looking back I have been very teacher centered, in this module students will get more control.”

At a network meeting Pete said “I do not feel comfortable with the role-play where students act as atoms, join hands to represent molecules, and then cannot pass a door”. A bit later he said: “I would like to experience, to feel, how it is to do a role-play, can Ed demonstrate this for us?” Ed then explained the role-play and the teacher-developers performed it, and it was decided to include it in the material.

Pete also learned that starting with a context has potential or in his words: “I have forced myself to start with a context in the material and see what concepts will emerge… I am excited to see what it will bring for the students.”

Lisa focused on methodological issues in her responses. Although network meetings’ discourse continuously focused on student learning, Lisa was anxious about class enactment:

I find it a bit scary. Education was teacher controlled and now students have to come up with group activities themselves. In your own lessons you know from experience this will go like this and that like that, and students have difficulties with that section. Now you don’t have this knowledge in advance and honestly I have no idea where students are going to end up!

To this point her students did not work in groups, and in the interview before class use Lisa said: “I have never been enthusiastic about students working in larger groups, but these rotating group roles is an excellent idea.” At a network meeting, she also clearly articulated the advantage of larger groups for her own role in class: “The advantage of groups of four to five students is that it is easier. When groups are small and all come with questions to you, you get nuts.”

With respect to the learning material two issues are of importance to Lisa. First of all the use of a student logbook to monitor progress and to keep track of the student roles: “For each lesson one page. First students indicate the date of the period, the roles of all students in that lesson, planning, answers to questions, etc.” A bit later she stated: “It also helps students themselves to monitor the process and they can say, hey you were supposed to do this and did not do it.” A second important aspect for the learning material is the inclusion of open practical assignments. In the interview she said: “What I noticed last year is that during practical activities everything is ready and students sit down and look around to what the others are doing and copy this.” A bit later she said: “In the past students used all the things that were prepared…but now they need to think in advance about what to do and what materials are needed for this. That is attractive.”

Ed’s responses indicated that he learned it was possible to start from a context. It is not necessary to first explain the principles and then demonstrate these using a daily life example, as he often had done in the past as he observed in the interview:

…the concrete must precede other things—so first the context and then the concept and never the other way around. Yes, this was an eye opener and I must use this more often and I am doing this already. I no longer start with the tricks and thereafter the applications.

With respect to the learning material he noted that it is not always possible to find a good alternative for experiments: “I tried to find an alternative for the poisonous lead iodide, but did not succeed. Each alternative had shortcomings.” Ed also experienced that it was not easy creating and keeping internal consistency in the learning material, because a change at some point affected the rest.

Teacher Learning during the Class Enactment Phase

To organize the data the categories ‘teaching methodology’ and ‘learning materials and chemistry content’ were used. A summary of the results is presented in Table 4.

Pete was especially happy about cooperative learning, enabling him to assist individual groups. Although he noted that students initially did not cooperate effectively, and did not divide the tasks at hand:

I noted that three students watched a colleague who poured a solution in a beaker, another solution in a test tube and then mixed these in the beaker. Eight eyes then saw that the color changed to yellow. This took 10 min and was not very effective for four students.

Learning cooperative skills requires time and specific attention, as he said: “After some time cooperation did go better. Students knew their roles and adhered to these.” After each period he collected the logbooks and went over each of them. He marked the answers to questions, commented on performed activities, wrote down suggestions for the next period and question marked passages he was dissatisfied with. What struck him was that each group at the beginning of a period first looked at his comments and then rectified or supplemented those parts he had marked. He noted that “connecting to and building upon what students had done in the previous period occurred therefore automatically.” Pete did not use the role-play because he argued that by the time his students reached this section he believed it would not contribute to students’ learning.

An innovative element in the material for Pete was that “the module does connect to students’ life world.” Pete’s students were very positive about the module and worked enthusiastically and hard, “Sir, can’t we do this more often, and why didn’t we do this earlier” was one of the expressions used by students. Pete mentioned another strong aspect in the material: “Students had to look back at what was done, they had to sit down and consider whether they had done what was required, and if not think of how to solve it… there was feedback on their own action.” Students also had to carry the consequences when they were not properly prepared, so when students came to Pete asking what to do, he responded: “Well, that is something you should have done yesterday afternoon.” He learned that written instructions in the material need to be explicit and clear, if not students need extra teacher support: “What I noticed is that when the material contains clear instructions, you only need half the manpower. That is what I really learned.” Also with respect to cooperation in the groups the material has to be clear as Pete in a network meeting said: “What you see is that some students manage to behave in such a manner that the work is done by others. The assignments should be formulated in such a way that each member takes responsibility for it.” Because of time constraints, assessment of the leaning outcomes was not possible. The groups prepared a poster and presented this to their colleagues, but no time was left for a written test.

Lisa was particularly satisfied about the cooperative group work, both about the process and about the opportunities it provided for the teacher to monitor the content of the group work, or in her words: “The fact that the students had to consult the group and then continued working, and this cooperation worked out quite well.” The enthusiasm of her students strengthened her opinions regarding the usefulness of context-concept learning and cooperative group work. After each period she collected the logbooks, went over the students’ answers and made comments about the content and the progress: “In the logbook I jotted down how satisfied I was with their work.” She assessed students’ answers to the module questions by marking their logbooks after the module was completed. This resulted in leveling out of the final grades.

Lisa did not let her students do the role-play in her classes, as she did not think it would lead to a better understanding of the concept of chemical reaction, and she feared unrest in class during the role-play activity. With respect to the learning material she noted that the logbook is important as it enabled the groups to work rather independent from the teacher. She also noted that all groups were very active and enthusiastic, and attributed this to the open practical activities in the material.

For Ed, class use did provide insights that could not have been anticipated before. Ed did not use group roles, and also left the formation of the groups to the students themselves. This resulted in groups of two and groups of five, and one student even worked alone. Ed decided not to let his students use the group logbooks, instead, the students could use their own personal way of presenting their answers. At a network meeting he said about the logbook: “This should be kept short, from such an administration one gets nuts or it will take a lot of time.” Ed assessed this work after completion of the module. To monitor and influence the learning processes in class he sat down with groups and observed their discussions.

Although Ed advocated the use of a role-play to model a chemical reaction, his opinion has changed due to students’ reactions to this activity. He discovered that students’ ability to think in terms of models was poorly developed: “I don’t know whether students find it difficult or not, but they don’t switch between reality and a model.” The role-play did not contribute to a better understanding of the concept of chemical reaction. It did create class unrest as students had to walk around.

Learning material needs to explicitly solicit for concepts, if not little learning will take place. Ed said about this in the interview: “Students do not reflect on experiences. And it was not called for to do so, so the material needs to explicitly ask for this.” Assessment of the final learning results was oral; the marking of the students’ answers after completion of the module also played a role in the final grade.

Teacher Learning during the Complete Development Process

Pete’s conception about the locus of control in class changed during the development process. He was initially teacher-centered, but he agreed to try cooperative learning where the control of the learning process lies within the groups. After class enactment he was very positive about cooperative learning, especially the use of a logbook which offered him a strong intervention tool to monitor and direct the groups’ learning. His comments and marks in the students’ logbook enabled each group to continue with the module without constant teacher intervention. He learned that student centered education can be effective, and that students’ motivation increased when they perceive ownership of their learning process. Linking chemistry with students’ experiential world created enthusiasm.

Pete used his initial general beliefs, for example about students acquiring a concept in a specific context and applying this in another context, to develop concrete student activities. In class, he experienced that students had difficulties developing the concepts and discovering structure between these concepts. This calls for scaffolding activities in the module or teacher interventions in class. After class enactment he realized that clear instruction saves teachers’ time as students can continue their activities without help. His initial skepticism with respect to the feasibility of students developing concepts ‘naturally’ from a context has disappeared, as he is now convinced that this approach is possible. The network discussions during the writing phase contributed in this transition process, but the turning point was clearly the way students responded to the module.

Lisa’s views on cooperative learning changed. Although she wanted to be less teacher-centered, she was initially hesitant because of the freedom students had. She learned that students were able to work rather independently in cooperative groups, and that the group logbooks helped her to monitor progress. She was however critical about two aspects. Firstly, in her practice, student results leveled out, meaning that there was little variation in the final grades, and these grades were different from those obtained by individual students on previous chapters. Therefore she proposed to change the grading system. Secondly, she felt that other teaching methodologies besides cooperative learning should be used in a school year to ensure diversity to accommodate differences in learning styles between students. Her confidence to engage in unknown teaching adventures received a boost.

Contrary to Pete and Lisa, Ed did not use cooperative learning. Instead he used a question-answers method in class to reveal student learning. This could be the reason that he did not mention to have learned something from cooperative learning as teaching methodology. He advocated the use of a role-play during the writing phase, used it in class, but was disappointed about the learning outcome. In future, he intends to use this as an activity for those students who need additional support to grasp a specific concept. To start a learning process from a context was the largest eye opener for him. He was not sure how students would respond to it, but it worked out very well, not only the learning results were as expected but student motivation was also high.

Discussion

The journey of developing student learning material and subsequent class use provides learning experiences for the teacher-developers. Our data mirrored Borko’s (2004) words: “Research using the individual teacher as the unit of analysis also indicates that meaningful learning is a slow and uncertain process for teachers…Some teachers change more than others through participation in professional development programs” (p. 6).

In this study, we showed that the teacher-developers changed with respect to the goals of chemistry education and with respect to teaching methodology and learning material. We see these changes as a learning process. In the next section we will first discuss teacher learning as the result of the writing and class enactment phases, and then turn to teacher learning and the five PCK domains.

Teacher Learning During the Development and Enactment of Learning Material

Our results show that developing a module can be seen as a training program in which personal characteristics, like knowledge, beliefs and dispositions toward reflection, form the starting point (Davis and Krajcik 2005). When teachers are not familiar with an innovation, they need to become equipped, for example through a training program (Joyce and Showers 1995) in which the goals are elucidated, vulnerable and difficult aspects are explained and discussed, opportunities for practice with materials is provided, and practicalities are exchanged. From our data we conclude that these aspects are addressed when teachers ‘in a network’ develop learning material. The two phases of the development process as indicated in Fig. 1, the writing phase and the enactment phase, were instrumental in these teacher-developers learning.

Writing phase. During the writing phase of the learning material, teachers learn by using the following five sources: (a) the written documents from the committee that initiated this context-concept renewal (Driessen and Meinema 2003); (b) the coach and in particular his specific expertise as a textbook writer; (c) experiences from each teacher who acted as inspiration for the others: teacher-developers build up an attitude of inquiry into one’s own practice, and engaged in deliberate reflection about a number of aspects of teaching and learning (Valli 1992); (d) discourse during network meetings about produced materials and envisaged class use; and (e) specific literature (e.g., on cooperative learning). These five sources constitute the components of what Clarke and Hollingsworth (2002) called the External Domain in their model. The teacher-developers constantly envisaged how their students will react to learning activities, what they will learn from these, and how practical problems can be solved. One can argue that the writing phase prepared teachers in an excellent way for class use of these materials.

Having quality learning material for students does not guarantee high-quality class enactment. Some scholars (Van den Akker 1988; Voogt 1993) had therefore included detailed lesson descriptions in their curriculum materials. This research demonstrates that developing a module provides the teacher-developers sufficient ‘how-to-do’ advice for their specific group of students. Practical advice about what to prepare, how to take it to class, how a logbook can be used to monitor student learning, and how to react to students, was over and over sought for and discussed in the network meetings. During such a process of discourse, writing, and reflecting, each teacher-developer becomes familiar with the operationalization of the educational goals in the instructional material and resources for own class use.

An innovation affecting classroom practices involves emotions (Schmidt and Datnow 2005). All teacher-developers were initially hesitant about the potential of the context-concept approach because it was perceived as a threat to their professional identities (Van Veen and Sleegers 2006). Initially they wondered whether it would be possible to develop context-based learning material for students to acquire concepts. Through discussion, their knowledge of the strong and weak aspects of the context-concept approach gradually increased and their beliefs changed. They wondered and conceived of how their students would react to a certain teaching methodology and how and what students would learn from a specific learning activity. The discussions about activities, the logbook and its possible use, and the simulation of the role-play during the network meetings, reduced anxiety as it demonstrated how these activities could be carried out in class. Before taking the module to class teacher-developers were convinced that it would be valuable for their students. This shows that the development of the module provides teacher-developers with ample opportunities to cope with emotional aspects of this specific reform, and prepares them for classroom practice.

The goals for chemistry education these three teacher-developers find important, like increasing students’ motivation, creating enthusiasm, and providing a learning motive by showing students how chemistry relates to daily life and what the relevance of the subject is, are in line with these of context-based approaches in other countries. Increasing students’ sense of ownership (Gilbert 2006) by providing learning process autonomy also becomes an important goal for these teacher-developers, as mirrored in the produced module in two ways. Students had to design and carry out their own research projects and report on their findings. One teacher-developer phrased it as follows: “you have to give the students the idea that they are the stationmaster.” Secondly, the organization in cooperative groups, with substantial group control on the learning process and product, makes exploring the module their own venture.

Class enactment phase. Traditionally, lesson preparation entails familiarization with the content and ways to engage students with assignments, all in a teacher controlled setting without much space for differentiation. In the new situation, students are guided by the learning material and the logbook, and can continue studying without constant teacher guidance. Each cooperative group designs its own research activities. This requires reflection on possible teacher roles (Coenders et al. 2008), and calls for a different kind of lesson preparation, in which a teacher establishes for example the feasibility of the groups’ research proposal in terms of materials, possible outcomes and safety. In traditional classes teachers talk to individual students, in this new setting groups will be addressed. A logbook is used to monitor group work.

Class enactment, after being involved in the development of the material, reinforces knowledge and beliefs learned during the writing phase, but we also noticed that in specific cases it could lead to incongruous experiences, as with the role-play. Ed observed that the role-play did not contribute to student learning. He now believes that a role-play will only contribute to learning in specific circumstances.

These three teacher-developers spent over 6 months developing a module, which for each of them contained innovative aspects. It was expected that the writing process and network discourse would create sufficient sense of ownership (Fullan 1998; Guskey 2000) to implement the module “as-is”. However, all decided to make changes before introducing the module in class, or changed it during class use. All had specific reasons for the changes made. Teacher-developers redesigned the module in accordance with their beliefs: ownership is at the end created personally, not in a group process.

Teacher Learning and the Five PCK Domains

Teacher learning can be expressed in the five PCK domains mentioned in the introduction.

-

1.

Knowledge of science curricula. Initially, before the development process started, the reported goals are rather general and vague, in terms of providing a learning motive (Gal’perin 1992), and permit different directions for their transfer to concrete learning material and teaching approaches. The nature of these goals are basically philosophical, of rationale and mission kind, and fit in the ideal curriculum representation from Goodlad (1979) and Van den Akker (1998). The articulated goals after the writing of the module, a process that involved the translation of the general ideas and notions into concrete learning activities and material for students, are more concrete, and reflect the written and the perceived curriculum. After the enactment of the module in class, the goals have shifted towards operational and experiential curriculum representations. These goals reflect the experiences from the interaction of students with the learning activities and material, and focus on what students should be able to do for learning and to reach understanding. For example, teachers express concerns about students’ ability to link up different concepts and the way this is regulated in the learning material and assignments. The construction of a coherent conceptual network by students is therefore mentioned as an important goal for chemistry education at this level.

-

2.

Knowledge of students’ understanding of science. Also with respect to student learning teacher-developers’ practice required scrutiny. In the current ‘normal’ curriculum, teachers, through year long experiences, know well what students learn, what is considered difficult, and how their own behavior, the textbook and other learning material all contribute to student learning. In the new module this is no longer obvious. Monitoring of the learning process and learning outcome on a daily basis is now imperative, not only to assess their own students, but also to improve the module.

-

3.

Knowledge of assessment. New ways of assessment suitable to establish student learning outcomes in context based education, like the logbook and posters, surfaced during the development of the module, and were put into practice in class.

-

4.

Knowledge of instructional strategies. Our results also show a conceptual change in general pedagogical terms during the development process. Cooperative learning, the pedagogy used in this specific module, was extensively discussed at network meetings. Even though initially hesitant, teacher-developers gradually became more enthusiastic as the specific advantages of cooperative learning surfaced, and class practicalities were resolved. The use of the logbook was something that was shaped in practice (Clermont et al. 1994; Van Driel et al. 1998) as the three teachers, after the writing phase, decided to use it in their classes in a specific and personalized way.

-

5.

Orientation to teaching subject matter. The conceptualization of science teaching and learning in epistemological terms has also changed. In their previous educational experiences, teacher-developers used learning material in which students learned concepts based on the subject matter structure (De Vos and Verdonk 1990). Now they developed and used materials starting from a context, in which students selected and discussed concepts from the experiences of their own research projects. Although this was one of the main reform goals (Driessen and Meinema 2003), teacher-developers were initially not convinced that it would be possible and would lead to meaningful learning. After class use they experienced the potential of this approach: students were enthusiastic, active, linked up chemistry with daily life, and acquired concepts. Of course the materials were not perceived perfect as can be seen in the recommendation to strengthen the construction of a coherent conceptual network by students.

In conclusion, teacher-developers’ practical knowledge (Barnett and Hodson 2001) and especially their knowledge in all five PCK domains (Grossman 1990; Magnusson et al. 1999) increased during the cycle of development of learning material and its use in class (Fig. 1).

In this study the development process was left to the group of teacher-developers and their coach. They decided on the manner in which the group operated. The focus of the network was on the development of student learning material. As a by-product the process served as a learning experience for the teacher-developers themselves. The question that surfaces is whether it is possible to design a development process of learning material that maximizes teacher learning and if so what distinctive qualities would such a process have?

References

Abell, S. K. (2008). Twenty years later: Does pedagogical content knowledge remain a useful idea? International Journal of Science Education, 30, 1405–1416.

Ball, D. L., & Cohen, D. K. (1996). Reform by the book: What is—or might be—the role of curriculum materials in teacher learning and instructional reform? Educational Researcher, 25, 6–14.

Barnett, J., & Hodson, D. (2001). Pedagogical context knowledge: Toward a fuller understanding of what good science teachers know. Science Education, 85, 426–453.

Bencze, L., & Hodson, D. (1999). Changing practice by changing practice: Toward more authentic science and science curriculum development. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 36, 521–539.

Bennett, J., & Lubben, F. (2006). Context-based chemistry: The Salters approach. International Journal of Science Education, 28, 999–1015.

Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: Mapping the terrain. Educational Researcher, 33(8), 3–15.

Campbell, B., Lazonby, J., Millar, R., Nicolson, P., Ramsden, J., & Waddington, D. (1994). Science: The Salters approach—a case study of the process of large scale curriculum development. Science Education, 78, 415–447.

Clarke, D., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 947–967.

Clermont, C. P., Borko, H., & Krajcik, J. S. (1994). Comparative-study of the pedagogical content knowledge of experienced and novice chemical demonstrators. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 31, 419–441.

Cochran, K. F., DeRuiter, J. A., & King, R. A. (1993). Pedagogical content knowing: An integrative model for teacher preparation. Journal of Teacher Education, 44, 263–272.

Coenders, F., Terlouw, C., & Dijkstra, S. (2008). Assessing teachers’ beliefs to facilitate the transition to a new chemistry curriculum: What do the teachers want? Journal of Science Teacher Education, 19, 317–335.

Cotton, D. R. E. (2006). Implementing curriculum guidance on environmental education: The importance of teachers’ beliefs. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38, 67–83.

Davis, E. A., & Krajcik, J. S. (2005). Designing educative curriculum materials to promote teacher learning. Educational Researcher, 34(3), 3–14.

De Vos, W., & Verdonk, A. H. (1990). Een vakstructuur van het schoolvak scheikunde. [A subject structure for high school chemistry]. TD beta, 8, 19–35.

Driessen, H. P. W., & Meinema, H. A. (2003). Chemie tussen context en concept. Ontwerpen voor vernieuwing. [Chemistry between context and concept. Design for renewal]. Enschede: SLO.

Fullan, M. G. (1998). The new meaning of educational change. London: Cassell.

Gal’perin, P. I. (1992). The problem of activity in Soviet psychology. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 30, 37–59.

George, J. M., & Lubben, F. (2002). Facilitating teachers’ professional growth through their involvement in creating context-based materials in science. International Journal of Educational Development, 22, 659–672.

Gess-Newsome, J. (1999). Pedagogical content knowledge: An introduction and orientation. In J. Gess-Newsome & N. G. Lederman (Eds.), Examining pedagogical content knowledge (pp. 3–17). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer.

Gilbert, J. K. (2006). On the nature of “context” in chemical education. International Journal of Science Education, 28, 957–976.

Goodlad, J. (1979). Curriculum enquiry: The study of curriculum practice. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Grossman, P. (1990). The making of a teacher: Teacher knowledge and teacher education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. California: Corwin Press.

Jeanpierre, B., Oberhauser, K., & Freeman, C. (2005). Characteristics of professional development that effect change in secondary science teachers’ classroom practices. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42, 668–690.

Joyce, B. R., & Showers, B. (1995). Student achievement through staff development: Fundamentals of school renewal. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Kelchtermans, G. (2005). Teachers’ emotions in educational reforms: Self-understanding, vulnerable commitment and micropolitical literacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21, 995–1006.

Loucks-Horsley, S., Hewson, P. W., Love, N., & Stiles, K. E. (1998). Designing professional development for teachers of science and mathematics. California: Corwin Press.

Lumpe, A. T. (2007). Research-based professional development: Teachers engaged in professional learning communities. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 18, 125–128.

Magnusson, S., Krajcik, J., & Borko, H. (1999). Nature, sources, and development of pedagogical content knowledge for science teaching. In J. Gess-Newsome & N. G. Lederman (Eds.), Examining pedagogical content knowledge (pp. 95–132). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer.

Meijer, P. C., Verloop, N., & Beijaard, D. (2002). Multi-method triangulation in a qualitative study on teachers’ practical knowledge: An attempt to increase internal validity. Quality & Quantity, 36, 145–167.

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62, 307–332.

Parchmann, I., Gräsel, C., Baer, A., Nentwig, P., Demuth, R., & Ralle, B. (2006). “Chemie im Kontext”: A symbiotic implementation of a context-based teaching and learning approach. International Journal of Science Education, 28, 1041–1062.

Park, S., & Oliver, J. (2008). Revisiting the conceptualisation of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK): PCK as a conceptual tool to understand teachers as professionals. Research in Science Education, 38, 261–284.

Pintó, R. (2005). Introducing curriculum innovations in science: Identifying teachers’ transformations and the design of related teacher education. Science Education, 89, 1–12.

Rousseau, C. K. (2004). Shared beliefs, conflict, and a retreat from reform: The story of a professional community of high school mathematics teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20, 783–796.

Sanders, M. (1993). Erroneous ideas about respiration—the teacher factor. Journal of research in science teaching, 30, 919–934.

Schmidt, M., & Datnow, A. (2005). Teachers’ sense-making about comprehensive school reform: The influence of emotions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21, 949–965.

Schneider, R. M., Krajcik, J., & Blumenfeld, P. (2005). Enacting reform-based science materials: The range of teacher enactments in reform classrooms. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42, 283–312.

Schwartz, A. T. (2006). Contextualized chemistry education: The American experience. International Journal of Science Education, 28, 977–998.

Shulman, S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57, 1–22.

Stronkhorst, R., & van den Akker, J. (2006). Effects of inservice education on improving science teaching in Swaziland. International Journal of Science Education, 28, 1771–1794.

Tal, R. T., Dori, Y. J., Keiny, S., & Zoller, U. (2001). Assessing conceptual change of teachers involved in STES education and curriculum development: The STEMS project approach. International Journal of Science Education, 23, 247–262.

Valli, L. E. (1992). Reflective teacher education: Cases and critiques. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Van den Akker, J. J. H. (1988). Ontwerp en implementatie van natuuronderwijs. [Design and implementation of science education.]. Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Van den Akker, J. J. H. (1998). The science curriculum: Between ideals and outcomes. In B. Frazer & K. Tobin (Eds.), International handbook of science education (pp. 421–448). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer.

Van Driel, J. H., Verloop, N., & De Vos, W. (1998). Developing science teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 35, 673–695.

Van Koten, G., de Kruijff, B., Driessen, H. P. W., Kerkstra, A., & Meinema, H. A. (2002). Bouwen aan scheikunde. Blauwdruk voor een aanzet tot vernieuwing van het vak scheikunde in de Tweede Fase van het HAVO en VWO. [Building on chemistry. A blueprint to come to a new chemistry high school curriculum.]. Enschede, The Netherlands: SLO.

Van Veen, K., & Sleegers, P. (2006). How does it feel? Teachers’ emotions in a context of change. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38, 85–111.

Veal, W. R. (2004). Beliefs and knowledge in chemistry teacher development. International Journal of Science Education, 26, 329–351.

Voogt, J. M. (1993). Courseware for an inquiry-based science curriculum. An implementation perspective. Enschede, The Netherlands: University of Twente.

Walberg, H. (1991). Improving school science in advanced and developing countries. Review of Educational Research, 61, 25–69.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research, design and methods (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Questionnaire A1

-

1.

What are according to you important goals for the module to be developed for Form 3 Junior High? What is it the students need to learn?

-

2.

What roles do you see for yourself as teacher using such a module, and what activities will you carry out?

-

3.

What roles do you see for your students? What do you want your students to do?

-

4.

How would you like to evaluate the learning results?

-

5.

Do you already have possible contexts in mind?

Interview guide A2

-

1.

What do you consider goals for chemistry education?

-

2.

How do you see your own role in this? What are your tasks?

-

3.

How do you see the role of your students in this?

-

4.

What can you say about the content of chemistry education:

-

What is the relation between context and concept?

-

What kind of teaching methodology do you consider appropriate?

-

What assessment techniques do you think are appropriate?

-

-

5.

Did you previously develop teacher guides?

-

6.

Did you use innovative materials developed by others?

Interview guide B

-

1.

What do you hope the module will bring:

-

For yourself?

-

For your students?

-

-

2.

What do you consider your role in this?

-

3.

What are for you the strong aspects of the module?

-

4.

What do you consider difficult, of critical aspect of the module?

-

5.

Why do you consider this module innovative?

-

6.

Did you learn yourself something during the writing phase about:

-

Pedagogy?

-

Tips to be used in class?

-

Chemistry content?

-

-

7.

Are you going to use cooperative learning, including logbook and student roles?

Interview guide C

-

1.

What was you reason to participate in the development of the module?

-

2.

In what classes did you use the module?

-

3.

How many periods did you use?

-

4.

Did you make any changes in the module beforehand?

-

5.

How did the students respond to the module?

-

6.

What is your opinion about the module? Would you use it again next year?

-

7.

What do you consider now to be innovative in the module?

-

8.

Cooperative learning:

-

How were the groups formed?

-

Did you se the logbook?

-

Did you use roles for group members?

-

Would you do the above aspect again a next time?

-

-

9.

How did you assess the learning results?

-

10.

How were the learning results, also compared to previous chapters and topics?

-

11.

Did you yourself, during the class enactment phase, learn something about:

-

Pedagogy?

-

Chemistry content?

-

Other things?

-

-

12.

How do you see the context-concept approach now?

-

13.

Anything you would like to add?

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Coenders, F., Terlouw, C., Dijkstra, S. et al. The Effects of the Design and Development of a Chemistry Curriculum Reform on Teachers’ Professional Growth: A Case Study. J Sci Teacher Educ 21, 535–557 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-010-9194-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-010-9194-z