Abstract

In this work, problems arising from performing trace element analysis using inductively coupled plasma—mass spectrometry with low measurement uncertainties are addressed. It is shown that some reference materials certified for massic concentration of lanthanides may have either deviating concentrations or underestimated measurement uncertainties. It is also shown that the choice of methods for sample preparation and linear regression to perform external calibration is affecting the outcome of the measurement results and their uncertainties. The results show that, from the selection of methods investigated in this work, the lowest measurement uncertainties can be achieved by using weighted linear regression to evaluate the calibration function and gravimetric dilutions of samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nuclear forensic science is a discipline that deals with providing information regarding chemical and physical characteristics of material connected to criminal investigations concerning e.g. illicit use of nuclear- and other radioactive material. In nuclear forensics, it is very important that the results from measurements, used for the interpretation of the materials in an investigation, are precise and accurate to stand up in court. Incorrectly estimated measurement uncertainties may lead a comparison between different materials or a comparison between a material and a nuclear forensic library to false conclusions, which at the end may result in wrong decisions. If the measurement uncertainties are underestimated, the comparison may give the result that an investigated material is different from another material or an entry in a nuclear forensic library even though they are similar. On the other hand, a measured material with an overestimated measurement uncertainty may not be possible to distinguish from another material even though they, in fact, are different. Therefore, it is imperative in nuclear forensics that the evaluated measurement uncertainty is as low as possible for a given measurement technique, but still accurate, to sharpen comparisons when materials are similar. For example, isotopic composition of uranium may be performed at an uncertainty level of 1–2% using gamma spectrometry [1] while mass spectrometric measurements using thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS) may reach uncertainty levels as low as 0.1% [2] Even so, the uncertainty of the gamma spectrometric measurement may be adequate if compared materials are different enough.

One important characteristic in nuclear material are trace elements either as contamination from the production process or from the ore [3, 4]. This signature may be used, together with other characteristics such as isotopic and molecular composition [5, 6] to identify the origin of the material or what type of processes the material has undergone. [7, 8]. For example, rare earth elements have previously been used to determine the origin of uranium [3, 9]. Another application is to use trace elements to compare different materials in order to establish a possible common origin or history.

A suitable technique for quantification of trace elements is inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Depending on the analyte, the quantification can be performed in different ways. In general, isotope dilution is known to provide the lowest measurement uncertainties [10]. However, for many elements, isotopically enriched reference materials are rare and for elements with single isotopes, isotope dilution is not possible. Standard addition is another technique that can be used, but require tedious measurements as each sample requires many measurements in order to obtain a result. Therefore, the most widely used technique for quantification is external calibration.

To achieve confidence in measurement results, quality assurance is essential. Quality control (QC) during measurement assures the instrumental status and the laboratory proficiency. In quantification of elements, a common QC is the use of a QC sample consisting of a certified reference material with a known and certified concentration. Preferably, this material should be of different supplier than the reference material used for the calibration. If the measured concentration of the control sample deviates from the certified concentration this deviation needs to be handled. The most common way of handling deviating results from QC samples is to discard the measurement sequence due to some identified instrumental or sample preparation problem. However, if the deviation remains during multiple measurements and no cause of the deviation can be identified, the anomaly may need to be treated differently. Kessel et al. [11] approached this problem in a similar context by increasing the measurement uncertainty when replicates of the same sample deviated in measured concentration. Another important aspect in performing accurate measurements is the evaluation of the measurement data. It is important that the choice of evaluation method provides accurate results and measurement uncertainties.

In this study, three certified reference materials of different origins have been measured using sector field ICP-MS (ICP-SF-MS) to show that, when attempting to minimize the measurement uncertainties, there are indications that the certified reference materials may not be, within the stated uncertainty, accurate in terms of concentrations. The study showed that the choice of linear regression method and method of sample preparation affects the quality of the measurement results at this level of uncertainty. The study was performed on the lanthanide series but the discussion would be transferable to any element measurable using e.g. ICP-MS.

Experimental

Instrumentation

The measurements were performed using an Element 2 (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) with a concentric nebulizer and a cyclonic spray chamber (both GlassExpansion, Melbourne, Australia). The conditions for the measurement setup can be found in Table 1. The instrument was tuned with a 1 ng g−1 cerium solution to maximize the signal of cerium while keeping the formation of CeO low, as cerium typically is one of the strongest oxide-formers of the lanthanide series [12, 13]. The magnitude of the CeO formation was 2.5% during the measurements.

Standard solutions

Three different certified reference materials (CRM) were measured. The standard solutions were Periodic Table Mix 3 for ICP (Sigma Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland), Spectrascan (Spectrascan, Inorganic Ventures, Christiansburg, USA) and CPAchem (CPAchem Ltd, Stara Zagora, Bulgaria), all certified by mass and traceable to NIST. The measurement uncertainties varied between 0.2 and 0.8%, k = 2, depending on analytes and brands. One of the standard solutions was used as the calibration standard and the other two standard solutions were used as QC samples. The standard solutions were diluted using MQ-water and in-house sub-boiled nitric acid to suitable concentrations. The calibration standard was diluted and measured at concentrations 0 pg g−1, 500 pg g−1, 1000 pg g−1, 1500 pg g−1, 2000 pg g−1 and 2500 pg g−1. The standard solutions used as QC samples were diluted to 100 pg g−1 and 1000 pg g−1. Rhodium was used as internal standard according to [3], and was added to all measured samples to a concentration of 1 ng g−1. All sample preparations were performed gravimetrically in order to reduce uncertainties compared to volumetric additions. However, uncertainty modelling was also done in order to compare volumetric and gravimetric additions from an uncertainty perspective. The analytical balance used in this work was a Mettler Toledo AX204 (Columbus, Ohio, US) with an uncertainty of 0.3 mg. It should be noted that in the case of measuring real samples, the calibration solutions as well as the QC samples should be matched to have the same matrix as the samples to be quantified. Preferentially, the QC samples should originate from a certified reference material of the same composition as the unknown samples.

Data evaluation

To achieve the lowest measurement uncertainties and to account for all uncertainty contributions, all data evaluation was performed offline. The raw intensity for each sample and isotope was extracted from the Element ICP-MS software (ver. 3.1.2.242). The mean value and standard deviation of the mean were calculated from the 500 data points from each sample and isotope resulting from 5 samples per peak and 100 runs. The intensities were corrected for dead-time using the method presented by Appelblad and Baxter [14]. Thereafter, the intensities were corrected for internal standard. To provide accurate internal standard corrections, the internal standard intensities were corrected for the added amount of internal standard, see Eq. 1.

Icorr,i,j is the intensity for isotope j in sample i corrected for internal standard, Ii,j is the dead-time corrected intensity of isotope j in sample i, IIS,i and IIS,blk are the dead-time corrected intensities of the internal standard in sample i and the blank sample and mIS,i and mIS,blk are the masses of the added internal standard in sample i and the blank sample.

To obtain a calibration curve, the measurement data from the calibration standards were used. Ordinary least squares regression (OLS) was performed using the Microsoft Excel 2016 function LINEST(). Additionally, linear regression was performed on the same data set using weighted least squares regression (WLS), weighted with the reciprocal variance of Icorr,i,j according to Sayago and Asuero [15], to fit the line

where ci,j and Icorr,I,j is the concentration and the measured intensity of isotope j in sample i, respectively. Using WLS regression, two calibration functions were calculated where uncertainties from the sample preparations performed gravimetrically and volumetrically, respectively, were included. For each method of linear regression, the slope, kj, and intercept, mj, and their corresponding uncertainties were evaluated. In the Excel OLS regression, the additional regression statistics was retrieved and used as uncertainties. For the WLS regression the uncertainties were evaluated according to Sayago and Asuero [15]. This was followed by the calculation of the limit of detection according to Miller and Miller [16]:

The results from the measurements of Standard solution 1 and 2 were used as quality control samples. The corrected intensities were used to calculate the concentrations using the calibration function. The calculated concentrations were compared to the certified values using the zeta score (ζ) [17]:

where cmeasured is the measured and calculated concentration and creference is the certified concentration and u(cmeasured) and u(creference) are their respective uncertainties. If \( \left| \zeta \right| \le 2 \) the measured value is consistent with the certified value within their respective uncertainties at 95% confidence level.

All uncertainties were evaluated according to ISO GUM [18] using the software GUM Workbench Pro (Metrodata GmbH, Weil am Rhein, Germany). All uncertainties are, unless stated otherwise, presented with a coverage factor k = 2, corresponding to an approximate 95% confidence level.

Results and discussion

Considerations for linear regression

Performing different linear regressions on the same calibration data provides the opportunity to evaluate the adequacy of the methods. For OLS to be valid there are a number of conditions that need to be fulfilled. Two important conditions for using OLS in calibration is homoscedasticity in the variance of the dependant variable (in this case Icorr,i,j) and that the variance in the independent variable (ci,j) is zero or very small compared to the variance in the dependant variable. The homoscedasticity condition implies that the absolute standard deviation of each point Icorr,i,j is constant throughout the calibration interval. Even though this is rarely true in many analytical methods, OLS is commonly used for constructing calibration curves [19]. In ICP-MS, the expected signal variance is similar in relative measures with the exception that the uncertainty is relatively higher close to zero. Since OLS gives each point in the calibration equal importance in the regression, the calibration points closer to zero will be given less weight than they should be given, even though these points are more certain in absolute measures. Whereas OLS might work well on heteroscedastic data in the high end of the calibration, since the equal weight gives the points in the high end of the calibration unreasonably high importance to the calibration model, the lower part of the calibration tends to be badly estimated which in turn will result in severely overestimated limits of detection [20,21,22].

It can be discussed what weight to use in the regression. Weighting with the reciprocal variance of the y data has been the classical method for WLS [15, 23]. This is also the weight that has been used throughout this work. However, using the variance for weighting may be difficult in cases where there is only one measurement for each x. In these cases, another weight has to be used. There are a number of suggestions of different weights such as 1/y, 1/x, 1/y2 [24, 25]. However, there may be very little statistical difference between using 1/y and 1/x for a linear model [24] and, moreover, using a weight such as 1/x may be impossible if the measurement of the blank, x = 0, is included in the calibration [26]. Therefore, the choice of weight is an important consideration for the evaluation of the calibration function.

Detection limits

The detection limits, calculated using Eq. 3, for each element and evaluated calibration functions based on OLS and WLS using gravimetric dilutions, can be seen in Fig. 1.

The detection limits calculated from the OLS method are orders of magnitude larger than the corresponding results using the WLS methods. This is the result from giving too little weight to calibration points close to the y axis in comparison to calibration points high up in concentration. This results in very high uncertainties in the intercept and also, in many cases, an intercept deviating immensely from the blank measurement. One consequence of this is that if for example a sample containing trace elements at 1 pg g−1, the question whether this concentration is detectable or not is dependent on the type of regression applied. If the sample was evaluated using OLS the concentration would be clearly below detection limit while if the sample was evaluated using WLS there would be quantifiable amounts present even though the same sample is measured, and the same measurement data is used to evaluate the calibration curve.

Quality control samples

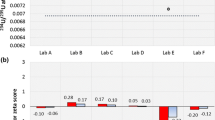

The results from the evaluated concentrations and uncertainties of the 1 ng g−1 QC samples using WLS and uncertainties from gravimetric sample preparation, together with corresponding certified values are shown in Fig. 2. The figure also displays the zeta score from the comparison between measured and certified values. The figure shows that there are large deviations in concentrations between the measured and certified values for some elements in Standard solution 1. When the zeta score is larger than 2, the difference between measured and certified values is not covered by their uncertainties on an approximate 95% confidence level. The difference cannot not be explained by polyatomic interferences since possible interferences should be cancelled out if the composition of the element standards are the same. To make sure that the isotopic composition of the rare earth elements were not fundamentally different or that no other interferences were present in the three solutions, all masses from 137 to 176 in a sample from each CRM were measured and compared. The examination showed no large differences in composition between the materials.

Measurement results and certified values of each element together with the calculated zeta score. The blue series correspond to Standard solution 1 and the orange series corresponds to Standard solution 2. The continuous lines are the measured values and the dashed lines are certified values. The bars corresponds to the calculated zeta scores

The results from Standard solution 2 do not show any significant differences in concentration between measured and certified values. This means that this CRM correlates well with the CRM used for calibration. The conclusion that can be drawn is that the stated concentrations of certain elements in Standard solution 1 are significantly different from those in the calibration solution, or that the uncertainty in one, or both, CRMs are underestimated.

The discrepancy between measured and certified concentrations in QC samples can be handled in different ways. According to ISO Guide 33:2015 [27], any discovered bias should primarily be reduced or eliminated, secondly corrected for and the additional uncertainty added to the uncertainty budget and thirdly, if these approaches are regarded as impossible to carry through, the bias should be included in the uncertainty budget [27]. Since it is difficult to determine which of the solutions that has the correct concentration, this bias was regarded as an additional uncertainty component. Therefore, an extra input quantity, δ, was added to the model equation for the calculation of the concentration of isotope j in sample i, ci,j, of the measured sample where mj is the intercept and kj is the slope of the calibration function and Icorr,i,j is the intensity of isotope j in the sample i corrected for dead-time and internal standard:

δ has value 0. In the measurement uncertainty software GUM Workbench, the uncertainty of δ, u(δ), was increased until the relative expanded uncertainty (k = 2) of the difference between measured concentration and certified concentration was 100%. This is equivalent to a zeta score of 2 (see Eq. 4).

This approach ensures that the result of the measurement of the QC sample corresponds to the certified value within uncertainties at the 95% confidence level. This methodology has previously been applied on replicate samples by Kessel et al. [11] in a similar fashion. It should be noted that if the choice was made to use the same CRM for the calibration as for the QC sample, this anomaly would not have been detected and the risk of reporting analytical results containing bias or underestimated uncertainties would be considerable.

The initial combined uncertainty when u(δ) = 0 varied between 0.7 and 1.5% depending on the measured isotope. The main part of the initial uncertainty originates from the uncertainty in the slope, k, of the calibration function. In cases where an extra uncertainty, u(δ), had to be added, the contribution to the total measurement uncertainty was, in most cases, dominated by this extra uncertainty. However, even though the extra uncertainty u(δ) was added, the combined expanded measurement uncertainties were rarely higher than 2%. The relative combined uncertainty for the final measurement uncertainty calculations can be seen in Fig. 3. The elements in Standard solution 1 that have obviously deviating uncertainties do all have an extra uncertainty, u(δ), added to the measurement uncertainty budget.

Relative uncertainties for the measured 1 ng g−1 control samples when an extra uncertainty has been added when necessary. The following data are evaluated using weighted linear regression: The triangles correspond to Standard solution 1, the circles to Standard solution 2 both with dilutions performed gravimetrically, the squares to Standard solution 1 in the case where dilutions were performed volumetrically. The diamonds correspond to the control sample from Standard solution 1 evaluated using OLS

The, in most cases, low measurement uncertainty is the result of diluting all the samples gravimetrically rather than volumetrically and using a CRM certified for mass. If the dilutions were performed volumetrically instead, assuming a combined uncertainty of 0.8%, k = 1, for volumes less than 1 ml and 0.4% for volumes greater than 5 ml, the combined uncertainty would increase to approximately 3%, see Fig. 3. The uncertainty was evaluated according to ISO 8655-6 [28] In this case, most of the uncertainty originates from the uncertainty in the addition of the internal standard and the uncertainty of the slope of the calibration function. In the case of volumetric sample preparation, there was no need for the extra uncertainty, u(δ), for any element at the 1 ng g−1 level.

The relative uncertainties in the data evaluated using OLS is, in general, following the relative uncertainties of the WLS evaluated data, see Fig. 3. This implies that at the 1 ng g−1 level, the ordinary least regression provides as accurate calibration as the weighted linear regression. The large difference can be seen in the evaluation of a 100 pg g−1 sample, see Fig. 4. The relative uncertainties for the results based on WLS are at the same level as for the 1 ng g−1 samples but for the results based on OLS the relative uncertainties are substantially higher than for the 1 ng g−1 sample. This is a result of the large uncertainty in the intercept that follows when performing an OLS on heteroscedastic data [29].

Relative uncertainties for the measured 100 pg g−1 control samples when an extra uncertainty has been added when necessary. The following data are evaluated using WLS: The triangles correspond to Standard solution 1, the circles to Standard solution 2 both with dilutions performed gravimetrically and the squares to Standard solution 1 in the case where dilutions were performed volumetrically. The diamonds correspond to the control sample from Standard solution 1 evaluated using OLS

Of course, the easy option to evaluate the measurement results is to use the software of the ICP-MS instrument. This method, however, does not provide the full picture of the uncertainty estimation, i.e. it is not fully transparent to the analyst. The software does not ask for any uncertainty of the dead-time, which, even though it may be small, may affect the overall uncertainty at high count rates. Further, the software does not include any uncertainty from the linear regression into the calculations of the sample concentration and does not give any room for corrections due to addition of the internal standard, which, at least for volumetric additions, is a substantial part of the uncertainty. The uncertainty provided by the software is based on the standard deviation (not the standard deviation of the mean) of the calculated concentrations for each sweep, which basically is the uncertainty of the blank subtracted measured intensity. These uncertainties are, in general, larger than the uncertainties from the volumetrically prepared samples and the uncertainties are, in fact, evaluated on the wrong assumptions, including uncertainties that can be made smaller and leaving out uncertainties that may be significant.

An example of when this methodology has been applied to measurements of trace elements in a uranium matrix can be found in another published paper [30].

Conclusions

Since nuclear forensic evidence, like all evidence presented in a court of law, need to be defensible, it is important that the results and the attached uncertainties are correctly evaluated. This work shows that to perform accurate and precise measurements of elements using ICP-MS, the data evaluation should be made manually with careful considerations regarding sample preparation and choice of regression method prior to performing the measurements, to be able to retrieve correct information from the measurements.

In this paper, it is shown that gravimetric sample preparation is preferred over volumetric sample preparation to achieve the lowest measurement uncertainties and that OLS provides large measurement uncertainties at low concentrations and unrealistically high detection limits. However, depending on the purpose and thus the requirements of the measurement, work effort might be saved if volumetric sample preparations are done but then on the cost of higher measurement uncertainties.

The study also shows that careful quality control is imperative to measurements at this uncertainty level. The risk of biases due to inconsistencies in the certified reference materials needs to be carefully monitored and attended. In this study, the bias was addressed by adding an extra uncertainty to the calculated concentration since it was not possible to know which of the certified reference materials that was deviating either in the value of the certified concentration or in its uncertainty. The discrepancy between the deviating CRMs would not have been observed if volumetric sample preparation had been done.

References

Abousahl S, Michiels A, Bickel M, Gunnink R, Verplancke J (1996) Applicability and limits of the MGAU code for the determination of the enrichment of uranium samples. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A 368:443–448

Bürger S, Essex RM, Mathew KJ, Richter S, Thomas RB (2010) Implementation of guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement (GUM) to multi-collector TIMS uranium isotope ratio metrology. Int J Mass Spectrom 294:65–76

Varga Z, Wallenius M, Mayer K (2010) Origin assessment of uranium ore concentrates based on their rare-earth elemental impurity pattern. Radiochim Acta 98:771–778

Spano TL, Simonetti A, Corcoran L, Smith PH, Lewis SR, Burns PC (2018) Comparative chemical and structural analyses of two uranium dioxide fuel pellets. J Nucl Mater 518:149–161

Mayer K, Wallenius M, Varga Z (2015) Interviewing a silent (Radioactive) witness through nuclear forensic analysis. Anal Chem 87:11605–11610

Kristo MJ, Gaffney AM, Marks N, Knight K, Cassata WS, Hutcheon ID (2016) Nuclear forensic science: analysis of nuclear material out of regulatory control. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 44:555–579

Varga Z, Krajko J, Peńkin M, Novák M, Eke Z, Wallenius M, Mayer K (2017) Identification of uranium signatures relevant for nuclear safeguards and forensics. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 312:639–654

Healey G, Button P (2013) Change in impurities observed during the refining and conversion processes. Esarda Bull 49:57–65

Mercadier J, Cuney M, Lach P, Boiron M-C, Bonhoure J, Richard A, Leisen M, Kister P (2011) Origin of uranium deposits revealed by their rare earth element signature. Terra Nova 23:264–269

Vogl J, Pritzkow W (2010) Isotope dilution mass spectrometry—a primary method of measurement and its role for RM certification. J Meter Soc India 25:135–164

Kessel R, Berglund M, Wellum R (2008) Application of consistency checking to evaluation of uncertainty in multiple replicate measurements. Accred Qual Assur 13:293–298

Dulski P (1994) Interferences of oxide, hydroxide and chloride analyte species in the determination of rare earth elements in geological samples by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Fresenius J Anal Chem 350:194–203

Longerich H, Fryer B, Strong D, Kantipuly C (1987) Effects of operating conditions on the determination of the rare earth elements by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Spectrochim Acta 42B:75–92

Appelblad P, Baxter D (2000) A model for calculating dead-time and mass discrimination correction factors from inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry calibration curves. J Anal At Spectrom 15:557–560

Sayago A, Asuero A (2004) Fitting straight lines with replicated observations by linear regression: part II. Test Homog Var Crit Rev Anal Chem 34:133–146

Miller JN, Miller JC (2010) Statistics and chemometrics for analytical chemistry, 6th edn. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow. ISBN 978-0-273-73042-2

ISO 13528:2015 (2015) Statistical methods for use in proficiency testing by interlaboratory comparison. The International Organization for Standardization, Geneva

ISO/IEC Guide 98-3:2008 (2008) Uncertainty of measurement—Part 3: guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement. The International Organization for Standardization, Geneva

Raposo F (2016) Evaluation of analytical calibration based on least-squares linear regression for instrumental techniques: a tutorial review. Trends Anal Chem 77:167–185

Zorn ME, Gibbons RD, Sonzogni WC (1997) Weighted least-squares approach to calculating limits of detection and quantification by modeling variability as a function of concentration. Anal Chem 69:3069–3075

Rajaković LV, Marković DD, Rajaković-Ognjanović VN, Antanasijević DZ (2012) Review: the approaches for estimation of limit of detection for ICP-MS trace analysis of arsenic. Talanta 102:79–87

del Río Bocio F J, Riu J, Boqué R, Rius FX (2003) Limits of detection in linear regression with errors in the concentration. J Chemom 17:413–421

Deming WE (1964) Statistical adjustment of data. Dover, New York

Almeida AM, Castel-Branco MM, Falcão AC (2002) Linear regression for calibration lines revisited: weighting schemes for bioanalytical methods. J Chromatogr B 774:215–222

Asuero AG, González G (2007) Fitting straight lines with replicated observations by linear regression. III. Weight Data Crit Rev Anal Chem 37:143–172

Tellinghuisen J (2008) Weighted least squares in calibration: the problem with using “quality coefficients” to select weighting formulas. J Chromatogr B 872:162–166

ISO Guide 33:2015 (2015) Reference materials—good practice in using reference materials. The International Organization for Standardization, Geneva

ISO 8655–6:2002 (2002) Piston-operated volumetric apparatus—Part 6: gravimetric methods for the determination of measurement error, the International Organization for Standardization. Switzerland, Geneva

Ketkar SN, Bzik TJ (2000) Calibration of analytical instruments. Impact of nonconstant variance in calibration data. Anal Chem 72:4762–4765

Vesterlund A, Ramebäck H (2019) Avoiding polyatomic interferences in measurements of lanthanides in uranium material for nuclear forensic purposes. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 321:723–731

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Swedish Defence Research Agency. The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, Project No. B40095, is gratefully acknowledged for funding this work. Thanks to Leif Persson, Department of Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics, Umeå University, for valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Vesterlund, A., Ramebäck, H. Achieving confidence in trace element analysis for nuclear forensic purposes: ICP-MS measurements using external calibration. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 322, 941–948 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-019-06795-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-019-06795-0