Abstract

Digitalisation is shaping the contemporary technological context of entrepreneurial activities, where firms grow through interacting with digital ecosystem stakeholders. This study investigates how incumbent firms seek entrepreneurial growth by re-configurating their knowledge bases in digital business ecosystems. We propose and develop a conceptual framework that blends the digital business ecosystem perspective and the knowledge-based view of the firm. Through a longitudinal case study of a Chinese textile manufacturing firm, we identify three pathways for entrepreneurial growth. The results contribute to the entrepreneurship literature by demonstrating how digital technologies foster corporate entrepreneurship in incumbent firms. The proposed framework extends the analytical power of the knowledge-based view by incorporating ecosystem elements into the firm’s internal and external knowledge management. The findings also generate relevant and actionable managerial implications for entrepreneurs, managers, and policymakers that are applicable in the context of digital business ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Entrepreneurship research aims at understanding the “discovery and exploitation of profitable opportunities” (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000:217). Entrepreneurial activities and processes are embedded in and shaped by various contexts, e.g., the institutional, cognitive, social, and technological environments where entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial organisations operate (Audretsch & Belitski, 2017; Audretsch et al., 2022a; Bejjani et al., 2023). Digitalisation serves as an important technological context of entrepreneurial activities. Digitalisation, sometimes considered as a synonym of Industry 4.0 (Franke et al., 2020; Hoe, 2019; Petrovic et al., 2019), is a socio-technical phenomenon driven by the advancement of digital technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), Big Data, and Cloud Computing (Autio, 2017; Hoe, 2019; Wamba et al., 2017). The progress of digital technologies engenders multiple effects on organisations, such as learning, innovation, and agility (Kuusisto, 2017). These have led to multi-faceted impact on entrepreneurship, e.g., in organisational status, behaviour, and performance (Audretsch et al., 2015).

A rich literature has been developed on the role of digital technologies in entrepreneurship (Nambisan, 2017; Zaheer et al., 2019). For example, Nambisan (2017) argues that digital transformation has resulted in less predefined entrepreneurial agency and less bounded entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. Autio et al. (2018) conclude that digital technologies promote technological affordance for the pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities through innovation and suggest considering entrepreneurial ecosystems as digital economy phenomena. The extant studies point at directions for further exploration: how, when and under what conditions digital technologies can support entrepreneurial growth (Audretsch et al., 2022c; Boccali et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023).

In terms of the way digital technologies empower firm growth, the phenomenon of digital business ecosystem (DBE) – the co-evolution and complementarity of organisations inter-connected through digital mechanisms and networks – have gained much attention (Senyo et al., 2019). Scholarly understandings of DBE focus primarily on the owner firm of and the entrepreneurs dependent on digital platforms (Kapoor & Agawal, 2017; Ecknardt et al., 2018; Cutolo & Kenney, 2021) – the shared digital infrastructure, architectures, and services that host business collaboration and operations, e.g., software-based systems and marketplaces such as Amazon and Uber (Lenkenhoff et al., 2018). However, there is limited research on non-platform-owner firms in the DBE regarding the way digital technologies empower their entrepreneurial processes (Cozzolino et al, 2021; Elia et al. 2021). These firms are the traditional producers of goods and services. They do not own digital platforms or rely on major digital platforms for sales, but they represent key stakeholders of the DBE. To develop our understanding on firm growth in DBE, this study investigates how the non-platform-owner firms pursue growth through entrepreneurial activities (Wright & Stigliani, 2013).

In terms of when digital technologies support firm growth, digital technologies empower entrepreneurial activities at different stages of development, from stand-up to start-up and scale-up (Autio et al., 2018). They satisfy firms’ various needs in the conception, gestation, infancy, and adolescence of business ideas (Audretsch et al., 2022a; Li et al., 2016). The extant literature focuses mainly on the early stages of entrepreneurship, such as new ventures (Nambisan & Baron, 2013, 2021) and start-ups (Cavallo et al., 2019; Dagnino & Mariani, 2010; Ghezzi & Cavallo, 2020). However, the latter stage of firm growth in incumbent firms also calls for our research attention and understanding (Audretsch et al., 2020). Often larger and older than early-stage enterprises, incumbent firms are established firms, and they need to overcome disadvantages in costs and flexibility and remain responsive to the dynamic business environment (Audretsch et al., 2021b). For this purpose, they seek new profitable opportunities and engage with entrepreneurial activities to sustain their growth (Caiazza et al, 2020). Entrepreneurial behaviours inside incumbent firms are conceptualised as corporate entrepreneurship (Kuratko et al., 2021). This includes the creation of new business ventures inside or outside the incumbent firm, as well as the development of new products, services, and processes within the firm (Audretsch et al., 2021b; Yildiz et al., 2021). In this study, we offer a focused analysis of entrepreneurial growth in incumbent firms – their exploitation of new opportunities through engagement with innovative activities.

Entrepreneurship process highlights the condition of generating profits from new or new combinations of knowledge (Audretsch & Caiazza, 2016). The development of digital technologies brings about increased flows of data and digital information. This improves the efficiency of knowledge sharing and transfer, promotes intra-organisational collaboration and inter-organisational cooperation (Czakon et al., 2020; Stojčić, 2021), and enhances the firm’s access to knowledge as well as learning capacity (Za et al., 2014). The knowledge-based view (KBV) theorises that a firm’s knowledge is the most strategic resource (Kogut & Zander, 1992) and that a firm’s knowledge base is the foundation for growth and competitive advantage (Eisenhardt & Santos, 2002). Through this lens, firms’ knowledge management processes constitute mechanisms of discovering, realising, and sustaining innovation opportunities for growth (Eisenhardt & Santos, 2002; Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2011; Mariani & Nambisan, 2021). This study combines the KBV with the DBE literature through incorporating the boundaryless integration of knowledge and learning within the firm’s ecosystem (Seyedghorban et al., 2020). Building on the KBV and drawing upon the wider literature on knowledge management, we develop a conceptual framework to address the following question:

RQ

How do incumbent firms pursue entrepreneurial growth through knowledge base reconfiguration in their digital business ecosystems?

To answer this question, we deploy an in-depth case study of a Chinese textile manufacturing firm. Through the case analysis, we identify three pathways for firms’ entrepreneurial growth in a DBE: Internal Exploitation, Internal Exploration and External Exploration. This study makes a relevant theoretical contribution as it develops a holistic conceptual framework blending the KBV and the DBE literatures. The results add to both theoretical foundation and empirical evidence of corporate entrepreneurship in incumbent firms. They also entail the firm’s knowledge resources and learning activities and extend the KBV’s analytical applicability in the contemporary technological context. Meanwhile, the study generates practical contributions in the guise of managerial implications for firms seeking entrepreneurial growth through the adoption of digital technologies, as well as policymakers designing entrepreneurship support.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on entrepreneurial growth, DBE, and the KBV. It also introduces the proposed conceptual framework. Section 3 discusses the research methodology. Section 4 presents the findings. Section 5 concludes this study, discusses its contributions, and points out limitations and directions for future research.

2 Literature review

2.1 Entrepreneurial growth in the digital era

It was highlighted in a growing number of studies that technological context plays a significant role in regional entrepreneurial dynamics and entrepreneurs’ decisions (Audretsch et al., 2019, 2020). Technologies serve as the facilitator of new business avenues, the mediator of entrepreneurial collaborations, and the outcome of entrepreneurial operations (Steininger, 2019). The availability of new technologies affects entrepreneurial trajectories and results (Audretsch et al., 2022b) in the firm’s transition and growth (Caiazza et al., 2020). The recent advancement of digital technologies is considered an important context for venture creation and operational processes as well as entrepreneurial growth. The development of digital artefacts, platforms and infrastructures connects multiple stakeholders in the production, distribution, and more widely business processes, thus translating into firm growth opportunities and competitive advantages (Petrovic et al., 2019).

Digital technologies support individual communication and facilitate collective knowledge building (Kimmerle et al., 2010). Intra-organisationally, this promotes knowledge creation and diffusion among employees (Za et al., 2014). Inter-organisationally, the exchange of information and sharing of knowledge across firm boundaries create a stronger basis for value co-creation among different stakeholders (Autio, 2017; Balaji & Roy, 2017), fostering inter-organisational cooperation. Therefore, the availability of digital technologies brings new opportunities to the firm’s innovation and growth (Mariani & Wamba, 2020) and leads to the digitalisation of entrepreneurial activities.

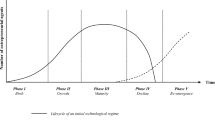

Firms’ growth continuum includes multiple stages, for which the impact of technologies varies. The pre-stage features latent and nascent entrepreneurship, where technologies are needed for access to initial information and networks and the validation of business ideas. The early-stage features emergent entrepreneurship with the critical task of transitioning from start-up to scale-up. The late stage focuses on growth entrepreneurship, where technologies are adopted to explore new opportunities and markets (Audretsch et al., 2020; Caiazza et al., 2020). The heterogeneity of entrepreneurial activities means that certain use of technologies may benefit early-stage firms by compensating for their limitation in resources and skills, while other technologies could be more useful for established firms to exploit accumulated knowledge and networks and pursue further growth (Audretsch et al., 2022b).

The extant literature on entrepreneurship in the digital era highlights the early stages of firm development, focusing on new venture ideas developed out of digital platforms and enabled by digital infrastructure (Nambisan, 2017). This stream of literature covers various aspects of the early-stage growth of enterprises. For example, Cavallo et al. (2019) discuss access to financing resources to foster the growth of digital start-ups. Ghezzi and Cavallo (2020) investigate business model innovation as a growth path for digital start-ups. However, incumbent firms, at a later stage of the growth continuum, are also important sources of entrepreneurship. Overlooked, neglected and uncommercialised knowledge in incumbent firms is a key source of entrepreneurial ideas and innovation (Acs et al., 2009; Audretsch & Keilbach, 2007). The literature on entrepreneurship in the digital era needs a broader range of analyses to cover different stages of entrepreneurship development (Audretsch et al., 2015). Compared to the early stages of firm growth, research on entrepreneurial growth in incumbent firms calls for more attention (Audretsch et al., 2020).

To fill this research gap, this study adopts the angle of incumbent firms and focuses on their pursuit of continuous growth in the digitalisation context. While entrepreneurs have a strong focus on external sources of ideas, the intrapreneurship research highlights both external and internal knowledge of the incumbent organisation (Audretsch et al., 2021b). This study develops a conceptual framework to understand the trajectories through which incumbent firms achieve entrepreneurial growth empowered by the adoption of digital technologies.

2.2 Digital business ecosystems

The advancement of digital technologies enables firms to strengthen the connection among internal units and develop links with external networks through sharing and exchange of digital information (Za et al., 2014). The firm’s pursuit of growth opportunities through adopting digital technologies calls for its absorption of information and knowledge embedded in the intensified social and organisational connectivity (Hoe, 2019; Leonardi & Treem, 2020). This echoes the business ecosystem concept (Moore, 1993), which highlights the co-evolution and complementarity of firms and their interconnected stakeholders in the business environment (Bejjani et al., 2023; Jacobides et al., 2018; Moore, 1993, 1996). Incorporating the significance of digital technologies into the business ecosystem, the research stream of DBE has gained recent attentions.

The DBE is defined as a business ecosystem where digital technologies serve as the key connecting mechanism of multiple entities (Senyo et al., 2019). It is a double-faceted concept and features characteristics of both digital ecosystem and business ecosystem. The digital aspect of DBE highlights the virtual environment centred around digital technologies as the core network links, and the business aspect focuses on organisational interdependence and value co-creation among stakeholders (Senyo et al., 2019).

Existing research on DBE highlights the key role of digital platforms (Koch & Windsperger, 2017; Nambisan, 2017) – the tools and services that connect stakeholders for collaboration in innovation and business activities. Empirical studies focus on the platform owner organisation, its coordination and leadership of the platform sponsor (Jacobides et al., 2018), and the DBE stakeholders organised around the platform – those platform-dependent firms (Gawer, 2021; Kenney & Zysman, 2020). However, many traditional incumbent firms are neither platform owners nor platform dependent. In a platform-based DBE, their roles are ecosystem members or complementors. These firms are important components of digital business networks. Recent studies show that the easily accessible platform resources can limit the market leaders’ development of unique resources and capabilities. As a result, the sustainable growth of incumbent firms’ business in the DBE calls for a shift of research focus beyond platform-centered structure and resources (Boudreau et al., 2021). To understand incumbent firms’ growth, further research is needed on the influence of digital technologies on the interactions among DBE stakeholders (Lenkenhoff et al., 2018). The DBE literature is also calling for theoretical development with the contextual focus, i.e., DBE-specific frameworks and models (Senyo et al., 2019).

Building on the research gap and ambiguity in the literature, this study adopts the perspective of firm-based ecosystem (Jacobides et al., 2018) and draws upon Adner’s (2017) ecosystem framework to observe the interactions among different stakeholders in the DBE. It combines the ecosystem perspective with the KBV and develops a DBE-specific framework for corporate entrepreneurship of incumbent firms. It investigates how the DBE surrounding incumbent firms affects their entrepreneurial processes in pursuing sustainable, innovation-led growth opportunities.

2.3 Knowledge-based view

The impact of digital technologies on the firm is largely manifested through its internal and external knowledge resources and management activities. Entrepreneurship in an incumbent firm means seeking innovation-led opportunities, e.g., through new products, services, or organisational transformation. This relies on new and existing knowledge and requires exploration and exploitation of knowledge resources within and outside the organisation (Caiazza et al., 2015, 2020; Chatterjee & Mariani, 2022; Mendes et al., 2023). The context of digitalisation makes learning and knowledge management essential for the discovery and execution of entrepreneurial opportunities (Audretsch et al., 2020; Mariani & Nambisan, 2021). For this purpose, incumbent firms make investments in internal knowledge and knowledge collaboration, promote organisational structures and learning processes that develop intrapreneurial capabilities, and engage in innovative activities to search, create, and capture growth opportunities (Audretsch et al., 2021b; Klofsten et al., 2021).

The KBV is adopted in various studies to understand firm growth and high performance empowered by digital technologies through the use of internal and external knowledge (Audretsch et al., 2021b; Li et al., 2016). The KBV considers knowledge as the most important strategic resource of the firm, due to the difficulty for competitors to imitate these resources (Grant, 1996; Nonaka & Toyama, 2003). It is argued that a dynamically changing environment makes it hard for the firm to maintain a long-term, sustainable competitive advantage. In such circumstances, incumbent firms need to adapt to changes through learning capabilities and activities (Eisenhardt & Santos, 2002). This adaptation is a process for the firm to reconfigure its knowledge base. This is realised through the operational approach of learning activities, where the firm re-combines existing knowledge or/and creates new knowledge (Eisenhardt & Santos, 2002; Penrose, 2009). At the fast-growth and late stage of entrepreneurship, incumbent firms aim at maintaining and regenerating innovation-led growth and seeking new opportunities through knowledge base reconfiguration. Therefore, the KBV provides a solid foundation to understand how incumbent firms can achieve corporate entrepreneurship through adopting digital technologies.

Extant studies in knowledge management tend to consider internal and externa knowledge separately (Audretsch et al., 2020). In this study, we offer a development of the literature by providing an integrated view on incumbent firms’ knowledge base and processes of knowledge management. This provides an opportunity to revisit the KBV as a traditional theory on management and organisation in a novel context – the focal firm’s DBE. By answering research questions in new organisational dynamics, traditional theories can be extended to incorporate the contemporary context of firm growth and competition.

2.4 An integrated KBV framework with an ecosystem perspective

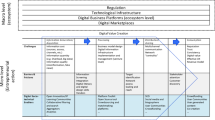

Based on the KBV, we propose two dimensions to explore the reconfiguration process of the incumbent firm’s knowledge base for its entrepreneurial growth in a DBE. The first dimension is knowledge resource, for which the firm has the option of focusing on resources owned by itself or resources that it can access through external cooperation. The second dimension is the firm’s learning activity, through which it can choose between reusing existing knowledge and creating new knowledge.

For each optional process of reconfiguration, we propose to observe the firm’s adaptation and transformation through the four key elements of ecosystem as structure: activities, actors, positions, and links (Adner, 2017). This integrates the ecosystem’s impact into the firm’s knowledge management processes for both internal-focused and external-involved practices. Among the four ecosystem elements: Activities are defined as value-proposition actions taken by entities within the ecosystem. This study investigates the reconfiguration of knowledge base and hence focuses on the focal firm’s key actions in adopting digital technologies and the corresponding knowledge management activities. These activities involve multiple Actors, including the focal firm and its ecosystem stakeholders, who play an important role in the reconfiguration process. Positions are the locations of these actors within the ecosystem, and Links describe the transfer of products and information among them in the reconfiguration process, digital or non-digital. Since the reconfiguration process focuses on the adoption of digital technologies, the transfer of technological information is considered part of the key activities. The transfer of information in the links among ecosystem actors refers to non-technological information (e.g., on product, market, and non-digital processes).

Figure 1 depicts the proposed two-dimensional framework of the firm’s process of knowledge base reconfiguration. The firm has four potential processes, each with a distinct focus on knowledge resource and learning activity: Process 1 features the reuse of the firm’s internal existing knowledge; Process 2 highlights the creation of new knowledge within the firm; Process 3 refers to the joint creation of new knowledge by the firm and its ecosystem stakeholders; and Process 4 means making use of existing knowledge of the firm’s ecosystem stakeholders. We use this framework to investigate how the firm pursues entrepreneurial growth in its DBE – its growth trajectories through reconfiguring knowledge base.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

This paper adopts an in-depth, qualitative case study (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007) to analyse firms’ entrepreneurial growth in DBEs. Case study method applies to contemporary and empirical research and incorporates the context of the phenomenon into the analysis (Yin, 2018). This paper analyses the subject of digitalisation, where the real-life context is relevant and important to the results. Entrepreneurial growth highlights the firm’s adaptation to the new context, with changes that involve many variables that cannot be tested with pre-set hypotheses. The firm’s processes of reconfiguring its knowledge resources and learning activities require an in-depth investigation and include qualitatively different types instead of quantified variation (King et al., 1994).

Our research uses a continuous process for data collection over a six-year period. This timeframe corresponds to the case firm’s digital transformation and allows key actions and changes to be captured. It guarantees live data for tracking the firm’s adaptation and gives the case study a longitudinal nature (Pettigrew, 1995). The theoretical foundation of this research is the KBV, which highlights the firm-specific history and path in knowledge accumulation and deployment. Our collected data covers the firm’s development history in the past four decades since its foundation. This allows the firm’s historical path in knowledge acquisition and accumulation to be taken into consideration.

3.2 Case selection

This study selected a Chinese textile manufacturing firm for the case analysis. Compared to the global leaders in digitalisation, e.g., the U.S., Germany and Sweden, Chinese firms are still catching up in terms of technological talents and resources (software and hardware), investment in manufacturing R&D, and cross-field collaboration (Chinese Academy of Engineering, 2018). Hence, the development of DBEs is at an emerging stage – achieving fast growth while at a mid-level on average. This is represented by the limited technological resources of various ecosystem stakeholders and the network connections among them (Chinese Academy of Engineering, 2018). This provides the research setting with rich materials of the learning and adaptation of firms within the DBE, demonstrating both progress and challenges of the process.

The case firm—Wensli—was chosen based on its achievement of fast, continuous growth and constant innovation empowered by new knowledge and technologies. The firm was founded in 1979 in Hangzhou as a township and village enterprise (TVE), specialised in the manufacturing of textile and clothing products based on silk materials. After privatisation in 2003, it operated as a family business and went public in 2021 (Wensli Group, 2021). Wensli has maintained a leading position in both revenue and brand awareness in the Chinese textile industry, ranked among the top 500 Chinese private enterprises for consecutive years (Wensli Group, 2015). The firm has made dedicated efforts on digital transformation since 2015. Its business development demonstrated increasing knowledge intensity (e.g., in new product, service, network cooperation and business portfolio), which makes it a good example for dynamic learning and adaptation. Its process of adopting digital tools and platforms illustrates the focus of adaptations and transformations in the industry and reflects the characteristics of Chinese textile firms.

Wensli has built strong network connections with multiple stakeholders in its DBE. This has been achieved through its in-house R&D infrastructure, long-term partnerships with local suppliers, research collaborators, and both commercial and business consumers. Its current transformation focuses on building an AI-based platform to integrate the design, manufacturing, and sales of silk textile products to connect internal designers, external suppliers, and customers. It has been involved in a wide range of inter-organisational cooperation, both nationally and internationally, and hence serves as a representative case firm for our analysis of the different processes in the proposed conceptual framework.

3.3 Data collection

This research collected primary data through semi-structured interviews and field visits. Field research allows researchers to be present and embedded in the context analysed to explore the interconnectedness of observations (Pettigrew, 1995). Multiple field visits were conducted by the research team to facilitate the understanding of new products and processes supported by digital technologies, and for maintaining communication with the management team for timely update and feedback. To track the case firm’s process of transformation and growth, the collection of interviews started in June 2015 and continued until November 2020, with a total duration of 26.5 h of communication.

A case study protocol was developed to guide the data collection process, including the procedure and focus of interviews and visits. The case firm was approached via the alumni network of a local university. Through its existing mechanism of termly communication with research partners, the research team conducted 10 in person visits to the firm between 2015 and 2019. The interviews conducted in person were integrated with one additional interview in 2020 that was conducted online due to restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic. The onsite visits allowed in-depth discussion with the firm and yielded longer interviews (1.5 to 5 h). The design of interview questions followed the proposed conceptual framework (Fig. 1).

Early interviews focused on the strategic planning of the firm’s digital transformation. Key members of the top management team were selected as interviewees because of their strategic leader roles in the corresponding decision-making process. As the digital transformation unfolded, operational-level managers were then interviewed to gain insights on specific changes in the firm’s activities and routines. Table 1 summarises the data collection process of both primary and secondary data.

3.4 Data analysis—data coding

The thematic analysis techniques of coding, categorising, and theme-building were applied to the collected data. This aimed at establishing connections and detecting patterns among observations. The coding process followed an abductive logic (Danermark et al., 2019; Linneberg & Korsgaard, 2019). It began with open coding to identify dominant categories and proceeded with axial coding guided by the proposed conceptual framework (Fig. 1). The literature served as a source of ideas to generate codes, delimit the field, and make sense of and theorize from categorization (Locke et al., 2022). The software NVivo was adopted to store and organise data. Coding was conducted and cross-checked by 4 researchers in the team. Secondary data were collected and used for triangulation purpose. For example, company reports and IPO prospectus were used to verify the internal transformation of the firm, and local news provided evidence of the firm’s cooperation with ecosystem partners. Evidence was kept chained with theoretical constructs and the process of analysis featured continuous refinement. The coding results were verified among collaborating researchers to ensure consistency, and the primary data were triangulated with secondary data to improve the reliability of analysis results (Yin, 2018). Figure 2 presents the main coding results.

4 Findings and discussion

The results of data analysis verified the conceptual framework, and the findings are presented in Fig. 3. Wensli started in 2015 to introduce digital technologies into its business and operations processes. By 2021, the firm had adopted a wide range of digital technologies in production, distribution, marketing, and service. The main achievements through entrepreneurial growth include digital distribution and marketing, digital production, and digital service. Digital distribution and marketing extended Wensli’s business-to-business market through target marketing and sales. Digital production allowed Wensli to enter a new market of digital printing machinery and diversified its business portfolio. Digital service expanded Wensli’s business-to-consumer market through personalised design. The new system equipped with digital technologies enabled Wensli to initiate a new consumer-to-manufacturer business model. The four processes of knowledge base reconfiguration were observed in Wensli’s digital transformation and are discussed below.

4.1 Process framework for knowledge base reconfiguration

4.1.1 Process 1: reusing internal existing knowledge

In this process of the firm’s knowledge base reconfiguration, the key learning activities showed a focus on knowledge application. This process was realised through fundamental changes in the firm’s organisational structure and involved the key sub-processes of reactivating and integrating knowledge. In the DBE, the key actors involved in this process include the focal firm in the position of non-digital knowledge provider, the external software suppliers in the position of digital knowledge provider, and customers who are directly involved through the digital platform.

Wensli’s development of digital distribution featured the reuse of existing knowledge of its employees, realised via a mobile app platform. This digital platform allowed quick and easy sharing of product information (e.g., descriptions and photos) and facilitated the salespersons’ direct interaction with customers. The digital tool also enabled order placement and payment via QR code, making transactions easier and faster. The sales record is attached to the salesperson’s individual profile and linked with performance data for incentives (e.g., commissions). The adoption of digital distribution promoted the link with customers and improved customer engagement and retention. At the same time, it established a strong connection between staff performance and evaluation, which improved the flexibility, efficiency, and motivation of employees’ engagement in sales activities.

“With the Internet Plus infrastructure, we put every employee in the position of a salesperson…” (CEO)

“Once the transaction is complete, the sales record will be immediately transferred to the employee’s performance record…” (General Manager)

A similar process was observed in Wensli’s development of digital marketing. With the digital platform of a mobile app, employees were required to share advertising articles with the customer network. The data of reads, likes, and reposts of the shared articles were collected and analysed for management purposes. Wensli’s accumulated expertise on silk products and customer communities allowed it to tailor product types and categories to particular needs of business customers and achieve target marketing. This development was based on the information collected through the digital tool.

“The mobile app is managed by our brand centre... It is used to facilitate and monitor employees’ participation in promoting products and services. Employees are required to repost and share marketing articles on a daily basis through the app, the record of which is checked every week, and incentives will be provided to those who perform well.” (General Manager)

4.1.2 Process 2: creation of new knowledge within the firm

This process focuses on the activities of knowledge renewal, realised through the establishment of new R&D routines and relied on the sub-processes of extending the firm’s internal knowledge and coordinating firm resources and activities for the exploration. In the DBE, the key actors in this process include the focal firm in the position of digital knowledge provider and the external hardware provider (a local machinery supplier) in the position of digital knowledge complementor. Another actor directly involved was the subcontract manufacturer of in-process products (with no digital elements). The subcontractors were needed for the focal firm to concentrate resources on the exploration of digital knowledge. In the DBE, these subcontractors took the position of non-digital knowledge provider.

The process was observed in Wensli’s development of digital production. Wensli established product lines with digital printing technology and an AI-based colour system. The digital printing software was developed by Wensli’s newly established sub-company which focuses on the R&D of digital technologies. The software allowed Wensli to apply digital printing machinery available in the market to silk materials. With digital printing machines purchased from a local supplier, Wensli adapted the equipment for the manufacturing of its own products. During this process, digital technologies played the role of enhancing the knowledge intensity in the product and providing a foundation for production data standardisation. The digital printing machinery for silk materials was then made available to the sector as a new product of Wensli, together with the supply of digital printing software and production training to business customers. This diversified the firm’s business portfolio.

“In 2015, we set up a new sub-company dedicated to R&D on digital technologies…” (HR Dean)

“There are over ten research groups in it, each in charge of a new product/service line based on digital technologies, and digital printing is one of them.” (General Manager)

“We set up a new factory dedicated to production lines with the digital printing system…” (CEO)

4.1.3 Process 3: joint creation of new knowledge with ecosystem stakeholders

This process focuses on creating new knowledge among different actors through knowledge combination. The realisation of this process requires active cooperation with partners for problem-solving. It involved the sub-processes of exchanging and synthesising knowledge. In the DBE, the key actors involved in this process include the focal firm, its R&D partners and customers. Both the focal firm and its R&D partners are in the position of digital knowledge provider.

Since 2018, Wensli has focused on the development of digital services. It jointly designed and created an AI-based mobile app with Microsoft China. This tool was embedded with a database of graphic elements of design. Customers can make simple choices over music and pictures to indicate individual characters, preferences, fashion styles, emotions, and moods. The AI platform matches the indicators with graphic elements in the database and generates personalised designs of products. The confirmed design was then sent to Wensli’s digital production line, where the exported design data were automatically transformed and recognised by digital printers. This digital platform initiated a systematic connection between customer needs and the design and manufacturing of products. Meanwhile, it significantly increased the efficiency of Wensli’s design activities. During this process, digital technologies played the role of codifying knowledge and serving as a platform for further innovation.

“Personalised design is time consuming and comes with costs. Using artificial intelligence to replace some steps in design significantly improved our efficiency.” (General Manager)

4.1.4 Process 4: using existing knowledge of ecosystem stakeholders

This process focuses on knowledge transfer. The realisation of this process relies on knowledge sourcing from other actors as well as the accommodation of the obtained knowledge for the firm’s specific use. In the DBE, the key actors in this process include the focal firm in the position of a non-digital knowledge provider, software suppliers in the position of digital knowledge providers, and both business and individual consumers in the position of customers.

This process was observed in various aspects of Wensli’s digital transformation. In both digital distribution and marketing, Wensli adopted mobile apps obtained from external software suppliers. The apps served as platforms for information sharing and facilitated the precision of marketing and collection of market information, e.g., customer preferences (Barbosa et al., 2022). For digital production, Wensli purchased the hardware – digital printing machines – from a local supplier and adapted the equipment with the software developed by themselves. For digital services, the jointly built platform was adapted from an existing AI tool developed by Microsoft China.

Observations from the case showed that adopting existing knowledge from ecosystem actors served as an important step in multiple aspects of the firm’s digitalisation. This process was supportive to many transformation activities.

“The digital printing machinery is produced by a local supplier, and we developed the software for it to work on silk materials…” (Director of Operations)

“To use big data for target marketing, we need to cooperate with external platforms for access to data…” (General Manager)

“For the sales activity through live streaming, we cooperated with the local TV company…” (General Manager)

4.2 Pathway framework for entrepreneurial growth

Through data analysis, all processes of the proposed framework are proven to be meaningful and important for the firm’s pursuit of entrepreneurial growth. However, the process of using existing knowledge of ecosystem actors (Process 4 in the proposed framework) itself does not qualify for a growth pathway. The entrepreneurial growth requires combination of the firm’s internal knowledge and its available external knowledge, and so the role of Process 4 in entrepreneurial growth is supportive to the other three processes. Based on the results of data analysis, we developed an entrepreneurial growth framework (see Fig. 3) with three identified pathways: Pathway I Internal Exploitation, Pathway II Internal Exploration, and Pathway III External Exploration. These pathways explain the firm’s pursuit of entrepreneurial growth empowered by digital technologies and the roles of key elements in its DBE.

4.2.1 Pathway I: internal exploitation

The first pathway highlights the application of internal knowledge of the firm. The growth can be achieved through increasing the efficiency of applying commercialised knowledge, but more importantly, it allows the exploitation of uncommercialised knowledge within the firm. In Wensli’s case, this was realised through facilitating individual-level differentiated knowledge to contribute to firm growth. The digital platform enabled the connection between sales performance to individual incentives and stimulated opportunity-seeking behaviours at the level of individual staff, pushing all employees to seek market opportunities for the firm growth.

“…the mobile app allowed employees to promote products easily and quickly through their personal networks.” (General Manager)

From the perspective of DBE, the interactions among the key actors were through the transfer of digital products from the software supplier to the focal firm, the transfer of non-digital products from the focal firm to customers, and the transfer of product information from the focal firm to both the suppliers and customers. In this pathway, the role of the DBE is to provide access to external technologies and facilitate the integration of relevant platforms and tools into the firm’s internal system.

“Our IT department manages all apps and the data generated through them. The team also tracks new software and tools available in the market that can add to the functions of our system…” (General Manager)

“We approach various technology holders for cooperation on a regular basis…” (General Manager)

From the perspective of knowledge management, digital technologies serve as a mechanism that allows the direct application of individual-level differential knowledge. For the scope and sustainability of the growth through this pathway, the firm needs to build mechanisms to convert such differential knowledge into firm-level integrated knowledge. Inside the firm, this requires supporting practices, including adjustment of internal structure and setting up new processes. Externally, the firm needs to extend links in the ecosystem to maintain and strengthen the value creation of the exploited (newly commercialised) knowledge. In Wensli’s case, examples of such links include access to technology and the channel for commercialisation and value creation with individual and business customers.

“The digital distribution required integration of the new channel and corresponding routines into the overall coordination of our internal system.” (General Manager)

“The new online channel expanded our customer range but led to a dispersed distribution of individual customers – the concentration and stability of sales through these channels are low… This caused uncertainty in terms of the sustainability of sales... To mitigate the uncertainty in sales through online channels, we need to maintain the customer base and develop personalised design and services to improve the differentiation of our products.” (General Manager)

From the perspective of entrepreneurial growth, this pathway highlights the role of digital technologies in facilitating intrapreneurship via unlocking knowledge embodied in employees for value creation. This is realised through fostering knowledge flows within and outside the organisation. Structural changes with the establishment of digital mechanisms in the firm allowed individual employees to efficiently interact with internal and external ecosystem actors. This facilitated decision-making and problem-solving, stimulated individual employees’ self-initiative, and promoted creativity and innovation (Audretsch et al., 2021b).

“Linking transaction records to individual profile largely helped with our management of sales and incentives to high-performing employees.” (HR Dean)

4.2.2 Pathway II: internal exploration

The second pathway focuses on internal innovation through creating new knowledge within the firm. The adoption of digital technologies was realised through the firm’s targeted R&D on digital tools and platforms. In this case, Wensli created digital knowledge itself and promoted differentiation through innovation in techniques and processes.

“Digital printing, compared to the traditional method used for silk products, has obvious advantages in terms of the richness of colours and the fineness of patterns. It is also more friendly to the environment and allows a higher level of production safety…" (Director of Operations)

“With digital printing technologies, we became able to manufacture in small batches and respond to market quickly.” (Director of Operations)

From the perspective of DBE, the links among ecosystem actors include the transfer of digital products from the digital knowledge complementor to the focal firm, and transfer of non-digital products from the non-digital knowledge provider to the focal firm. The focal firm transferred product and process information to both the digital knowledge complementor and the non-digital knowledge provider for the alignment of activities. In terms of the interactions among DBE actors, the focal firm plays the role of digital knowledge provider, and hence it has the flexibility to switch among available hardware suppliers in the market without over-relying on individual complementors. Yet a long and stable partnership with the complementor contributes to the sustainability of cooperation. For the link with the non-digital knowledge provider, it is important for the focal firm to provide support in product and process information, to achieve continuous and effective quality and process control. The main function of the DBE in this pathway is to assist the firm in commercialising the digital technology of its own development.

“Our cooperation with the local suppliers complements our own technology… and largely assisted the realization of our new ideas…” (General Manager)

From the perspective of knowledge management, the focal firm needs to dedicate resources to R&D and the update of key internal processes (digital production lines in Wensli’s case). Internally, this requires managerial support as well as the accumulation of knowledge and learning capabilities within the firm as the foundation of exploration. The mechanisms of knowledge creation played a key role (e.g., individuals and organisational processes and routines). For external knowledge management, the firm needs to access complementary knowledge to realise the value creation of its newly developed digital technologies (hardware in the form of digital printing machine in Wensli’s case). Meanwhile, for the concentration of resources on new knowledge (core knowledge for innovation-led growth), it also relies on suppliers for in-process products and non-core-knowledge value creation.

“In the past decades, Wensli has built up its capability in R&D and also paid close attention to the new tools/technologies available in the sector…” (CEO)

“We gradually transferred less knowledge-intensive manufacturing processes to local, subcontract suppliers, in order to concentrate on our core competences and technologies.” (General Manager)

From the perspective of entrepreneurial growth, the internal exploration pathway highlights the innovation-friendly corporate context of the incumbent firm (Kuratko et al., 2021). It requires the firm’s resource accumulation and investments in digital knowledge, skills, structure and processes. More importantly, intrapreneurial employees need a strong learning orientation to constantly search for new idea and commercialisation opportunities (Yildiz et al., 2021) with available technological infrastructure within the firm. In the process of digital transformation of incumbent firms, employers have important influence on the likelihood of intrapreneurship through cultivating an entrepreneurial culture in the organisation and encouraging an entrepreneurial mindset of employees (Urbig et al., 2021).

“Our CEO worked for many years as an engineer in textile manufacturing before joining Wensli, and hence he has a strong technology orientation…” (Assistant of CEO)

“He (the CEO) serves as the head of our research institute and has led various projects on digital technologies… the supervision and support are at the level of operational activities…” (General Manager)

4.2.3 Pathway III: external exploration

The third pathway highlights the joint creation of new knowledge between the firm and its ecosystem actors. This pathway involves using external existing knowledge, but simply obtaining it on a transaction basis was proven not sufficient for an entrepreneurial growth. The firm needs to achieve a higher extent of participation in learning activities, to allow a greater level of control over the outcomes as well as a significant impact on the firm’s resource base. Such an external exploration can bring innovation-led opportunities.

“It was not difficult for Microsoft China to adapt their existing software to create our AI tool. But the realisation of personalised products relied on our database of the design-patterns…” (General Manager)

“As the foundation of the new platform, our team spent a lot of time building a design-pattern database. It relied on our accumulated expertise in silk materials and the Chinese culture…” (General Manager)

From the perspective of DBE, the key actors in the DBE were linked through the transfer of digital products (and services) from the focal firm to customers, and the transfer of market information from customers to the focal firm. In addition to the new technology platform, other complementors are also required:

“We need to promote the new C-to-M (consumer-to-manufacturer) options to our consumers… More live streaming services would help to demonstrate our digital platform and train the consumers to familiarise with the new tool…” (General Manager)

“Our revenues and efficiency of the new C-to-M (consumer-to-manufacturer) model are currently limited by the non-digital, post-printing processing devices, as they cannot support small-scale production required by the personalised design… As a result, we had to postpone the production and delivery of some orders.” (General Manager)

From the perspective of knowledge management, the focal firm needs to coordinate its newly created and existing processes, e.g., the digital and non-digital production processes for the consistency of human and AI-based design in Wensli’s case. Hence the focus is the combination of internal and external knowledge. This starts with searching, tracking, and selecting available technologies accessible via the DBE with clear purposes and criteria. It then involves knowledge exchanging and synthesising, i.e., creating synthesis of knowledge from both sides to explore new ideas and solutions. This pathway also involves knowledge transfer, including the sourcing and accommodation of important information.

“We are constantly searching for potential co-operators. These include universities, research institutions and various companies...” (CEO)

“After discussion with a few organisations, we finally chose Microsoft China…” (General Manager)

“We worked closely with the Microsoft team... we are continuously expanding for more human emotional elements to be connected with and recognised by the auto-design app.” (General Manager)

From the perspective of entrepreneurial growth, this pathway highlights the digital capabilities of the incumbent firm. The cooperative innovation procedure demands the firm’s strategic alignment between its management and digital operations (Audretsch et al., 2022b) and coordination with various ecosystem partners for value creation and capture. This includes the management of digital and non-digital knowledge and interactions within and beyond organisational boundaries and the ability to take risks and drive changes for the joint search and commercialisation of digital opportunities. The digital capabilities also require agility in acting on markets with experiments, efficiently allocating and transferring resources, and effectively participating in various networks (Audretsch, et al., 2021b).

“As a private enterprise and benefiting from the support of the top management, our firm is flexible and highly efficient in approving and supporting R&D proposals, and our R&D personnel enjoy great autonomy...” (HR Dean)

“We encourage all employees to share and extend business networks for opportunities of new ideas and channels… Our successful cooperation with the top live streamers in China was established through an employee’s link…” (General Manager)

4.3 Entrepreneurial growth in digital business ecosystems

The case findings showed that each of the three pathways has led to entrepreneurial growth empowered by digital technologies, and they were also carried out simultaneously by the case firm to achieve large-scale innovation. The significance of the DBE in the firm’s entrepreneurial growth lies in the necessity of complementary knowledge accessible through the digital connections and interactions among actors in the ecosystem.

The impact of DBE on the firm’s entrepreneurial growth is twofold. First, it provides complementary knowledge to the focal firm. This could be digital knowledge (in Pathway I of the case study) or non-digital knowledge (in Pathway II). The case also showed further complementarity needs that create future opportunities for the firm’s continuous entrepreneurial growth. Second, the DBE facilitated and improved the interactions among the firm’s various knowledge management mechanisms, e.g., between internal and external processes and routines, and at individual and organisational levels. The consumer-to-manufacturer model achieved by the case firm through a combination of all three pathways provided an example of connecting customer preferences to the production line, a system that involves multiple knowledge management practices of the firm (knowledge application, transfer, exchange, synthesis etc.).

From the perspective of entrepreneurial growth, the three pathways reflect the characteristics of the incumbent firm, which are at a later stage compared to new ventures and start-ups. With a longer development history, their knowledge and learning capabilities accumulated in the early stages form the basis of the knowledge exploitation and exploration within the firm (for Pathway I and II). Where a culture and supporting mechanisms for innovation have been established, the firm would have a stronger foundation for joint R&D with its ecosystem partners (in Pathway III). Firms that have mature processes and routines of knowledge management and innovation activities can also expect smoother transitions in the internal system for the three pathways.

Based on the case findings, we use Fig. 4 to summarise Wensli’s digital transformation process, its DBE interactions, and the pathways of achieving entrepreneurial growth. Meanwhile, it illustrates the firm’s knowledge frontier in its DBE. This shows that the firm’s knowledge boundaries can be understood and managed from the perspective of entrepreneurial growth (Audretsch et al., 2021a; Zobel & Hagedoorn, 2020), and the proposed pathway framework provides a structure for such considerations.

5 Conclusions

This study incorporates the ecosystem perspective into the KBV framework, to create an integrated and holistic view of the incumbent firm’s pursuit for entrepreneurial growth through dynamic adaptation to digitalisation. It focuses on the firm’s process of reconfiguring its knowledge base to achieve digital transformation and adopts the key ecosystem elements to understand the process. Drawing upon the literature on corporate entrepreneurship, the KBV and DBE, we propose a conceptual framework for the systematic analysis of the incumbent firm’s entrepreneurial growth through digital transformation.

5.1 Theoretical contributions

This research makes multiple theoretical contributions. First, it contributes to the entrepreneurship literature: The proposed framework incorporates the firms’ digital networks and broadens the theoretical foundations of the role of technological context in promoting entrepreneurial activities (Audretsch et al., 2019, 2022a, 2022b). The focus on corporate entrepreneurship in the incumbent firm develops our understanding of entrepreneurial processes at later stages of the firm’s growth continuum. The case study adds to the empirical evidence of digital technologies’ roles in promoting the entrepreneurial environment (Audretsch et al., 2022a), in terms of management support, work discretion autonomy, rewards reinforcement, and organisational boundaries (Kuratko et al., 2021). It also demonstrates the effects of the firm’s digital capabilities in exploiting intrapreneurial opportunities through unlocking the neglected, incompletely commercialised knowledge in the incumbent firm (Audretsch et al., 2021a).

Second, this research contributes to the extant DBE literature: The proposed framework enhances the conceptual development of DBE-specific investigations (Senyo et al., 2019). The focus on non-platform-owner firms extends the current understanding on interactions among DBE stakeholders in promoting resource sharing and innovative cooperation for growth purpose (Lenkenhoff et al, 2018). The case study provides evidence of how the key elements of a DBE contribute to the focal firm’s knowledge base reconfiguration. This emphasizes the important effects of non-technology-owing firms’ digital connections on their knowledge management, and sheds light on the impact of the DBE on the sustainable growth and competitiveness of its stakeholder firms (Boudreau et al., 2021).

Third, this study extends the KBV’s analytical power in the contemporary context through developing the blended framework with ecosystem elements. It integrates the firm’s inter-connected business networks into its knowledge base, expands the observation and analysis beyond the firm level, bridges the discussion on knowledge boundaries and frontiers through digital connections and networks (Audretsch et al., 2021a), and provides a systematic approach to incorporate both internal and external knowledge management (Audretsch et al., 2020). The case study also enriches the understanding of the firm’s dynamic adaptation and transformation in the digitalisation context.

5.2 Managerial implications

The results of this research add to the current understanding of practitioners on the impact of digital technologies on technical processes in manufacturing firms (Zheng et al., 2021). The proposed framework could be used by entrepreneurs and managers to understand their strategic options when they operate in a DBE. It can guide the firm’s dynamic adaptation to the digital context in creating and delivering the value of Industry 4.0 (Mariani & Borghi, 2019). The case study demonstrates incumbent firms’ cultivation of a corporate environment that fosters intrapreneurship. It provides practical references for incumbent firms’ adoption of digital technologies and digital data to strengthen the links between performance and incentives and to achieve support for employees’ entrepreneurial intentions and execution (Urbig et al., 2021).

The three identified pathways provide structured references for the firm’s entrepreneurial decision-making in the pursuit of sustainable, innovation-led growth opportunities. They shed light on the firm’s development of effective knowledge management mechanisms and practices, including investing in internal knowledge and purchasing external knowledge (Caiazza, 2016), the recognition of internal tacit knowledge as well as the development of learning capabilities (Belitski et al., 2021). Within the contemporary DBE context, the firm can follow Pathway I to further exploit its core, non-digital knowledge to strengthen its competitive advantage. It can also follow the Pathway II and III, taking the position of digital-knowledge provider, to sustain entrepreneurial growth while avoiding dependence on external parties. The case study illustrates how to address the complex changes in these entrepreneurial processes, including products and services, organisational structure, business model, as well as the firm’s interactions with partners in the ecosystem (Belitski et al., 2021; Matt et al., 2015).

The research results can also be of interest for policymakers designing entrepreneurship and innovation policies. The focused analysis on incumbent firms in digitalisation provides references to policymakers in creating a supportive environment that accommodates the heterogeneity of entrepreneurship—the variation in contexts and stages (Audretsch et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). The demonstrated interactions among DBE actors in knowledge sharing and combination raise awareness of facilitation and investment in knowledge-creation activities (Audretsch & Link, 2012), as well as the cross-fertilisation of basic research, e.g., by R&D institutions, and applied research, e.g., by private-sector firms (Leyden & Menter, 2022). Governments can create opportunities for the integration of knowledge from different sources of research, establish mechanisms and provide incentives to promote DBE-based research, nurture network ties for flow of knowledge, and enhance interactions among various actors to share digital capabilities and co-create a comprehensive knowledge ecosystem (Leyden & Menter, 2018).

5.3 Limitation and direction for future research

This research investigates the firm’s digital transformation, which requires an in-depth analysis of a complex and continuous process. Therefore, our study adopts the single, longitudinal case study method. For the longitudinal study, the interview process could benefit from a higher frequency of communication, to enhance the real-time capture of activities and reduce omissions of details. To further develop the literature of the impact of technologies on the firm’s growth continuum, a future longitudinal study that compares the role of technologies in various stages of firm growth can provide a holistic view.

Following our proposed framework, multiple case studies can be conducted to enrich the understanding of the four reconfiguration processes and the pattern of changes in the ecosystem elements involved in each process. The framework can also be tested for analysing other types of resources in the firm’s resource pool and contribute to the understanding of boundaries, value creation and value appropriation in the interactions among DBE stakeholders.

The case study of this research focuses on a large firm, which has a mature management system. Future case studies can investigate small firms, as they may encounter more difficulties in the transformation process and modification of routines. For example, small firms may lack a well-established management information system, e.g., in terms of data format in production, quality control and accounting. Therefore, small firms may have different patterns in managing their digital transformation. This study investigates a case firm in the textile manufacturing industry. Future research can look at other industries with different levels of knowledge intensity to further explore the process of knowledge base reconfiguration.

References

Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15–30.

Adner, R. (2017). Ecosystem as structure: An actionable construct for strategy. Journal of Management, 43(1), 39–58.

Audretsch, D.B., Belitski, M., Caiazza, R., & Menter, M. (2022c). Call for Papers: Special issue on Entrepreneurial Growth, Value Creation and New Technologies. Retrieved 27 May 2023, from https://www.springer.com/journal/10961/updates/19860992

Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2017). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: Establishing the framework conditions. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 42, 1030–1051.

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., & Caiazza, R. (2021a). Start-ups, innovation and knowledge spillovers. Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(6), 1995–2016.

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., Caiazza, R., Guenther, C., & Menter, M. (2022b). Technology adoption over the stages of entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 14(4/5), 379–390.

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., Caiazza, R., Günther, C., & Menter, M. (2022a). From latent to emergent entrepreneurship: The importance of context. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121356.

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., Caiazza, R., & Lehmann, E. E. (2020). Knowledge management and entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(2), 373–385.

Audretsch, D., & Caiazza, R. (2016). Technology transfer and entrepreneurship: Cross-national analysis. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 41, 1247–1259.

Audretsch, D. B., Cunningham, J. A., Kuratko, D. F., Lehmann, E. E., & Menter, M. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: Economic, technological, and societal impacts. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(2), 313–325.

Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2007). The theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Journal of Management Studies, 44(7), 1242–1254.

Audretsch, D. B., Kuratko, D. F., & Link, A. N. (2015). Making sense of the elusive paradigm of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 45(4), 703–712.

Audretsch, D. B., Lehmann, E. E., Menter, M., & Wirsching, K. (2021b). Intrapreneurship and absorptive capacities: The dynamic effect of labor mobility. Technovation, 99, 102129.

Audretsch, D. B., & Link, A. N. (2012). Entrepreneurship and innovation: Public policy frameworks. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 37, 1–17.

Autio, E. (2017). Digitalisation, ecosystems, entrepreneurship and policy. Perspectives into Topical Issues In Society and Ways to Support Political Decision Making. Government’s Analysis, Research and Assessment Activities Policy Brief, 20/2017.

Autio, E., Nambisan, S., Thomas, L. D., & Wright, M. (2018). Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 72–95.

Balaji, M. S., & Roy, S. K. (2017). Value co-creation with Internet of Things technology in the retail industry. Journal of Marketing Management, 33(1–2), 7–31.

Barbosa, B., Saura, J.R., & Bennett, D. (2022). How do entrepreneurs perform digital marketing across the customer journey? A review and discussion of the main uses. The Journal of Technology Transfer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-022-09978-2

Bejjani, M., Göcke, L., & Menter, M. (2023). Digital entrepreneurial ecosystems: A systematic literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 189, 122372.

Belitski, M., Caiazza, R., & Lehmann, E. E. (2021). Knowledge frontiers and boundaries in entrepreneurship research. Small Business Economics, 56(2), 521–531.

Boudreau, K., Jeppesen, L. B., & Miric, M. (2021). The paradox of platform-based entrepreneurship: Competing while sharing resources. Retrieved 28 April, 2022, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3897435

Caiazza, R. (2016). A cross-national analysis of policies effecting innovation diffusion. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(6), 1406–1419.

Caiazza, R., Belitski, M., & Audretsch, D. B. (2020). From latent to emergent entrepreneurship: The knowledge spillover construction circle. Journal of Technology Transfer, 45(3), 694–704.

Caiazza, R., Richardson, A., & Audretsch, D. (2015). Knowledge effects on competitiveness: From firms to regional advantage. Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(6), 899–909.

Cavallo, A., Ghezzi, A., Dell’Era, C., & Pellizzoni, E. (2019). Fostering digital entrepreneurship from startup to scaleup: The role of venture capital funds and angel groups. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 145, 24–35.

Chatterjee, S., & Mariani, M. (2022). Exploring the influence of exploitative and explorative digital transformation on organization flexibility and competitiveness. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2022.3220946

Chinese Academy of Engineering. (2018). Research report on the development strategy of intelligent manufacturing in China's textile industry. Retrieved 28 April, 2022, from https://zhuanlishuju.oss-cn-qingdao.aliyuncs.com/

Cozzolino, A., Corbo, L., & Aversa, P. (2021). Digital platform-based ecosystems: The evolution of collaboration and competition between incumbent producers and entrant platforms. Journal of Business Research, 126, 385–400.

Cutolo, D., & Kenney, M. (2021). Platform-dependent entrepreneurs: Power asymmetries, risks, and strategies in the platform economy. Academy of Management Perspectives, 35(4), 584–605.

Dagnino, G.B. & Mariani, M. (2010). Coopetitive value creation in entrepreneurial contexts: the case of AlmaCube. In Coopetition. winning strategies for the 21st century (pp. 101–123). Edward Elgar.

Danermark, B., Ekström, M., & Karlsson, J.C. (2019). Explaining society: Critical realism in the social sciences. Routledge.

Eckhardt, J. T., Ciuchta, M. P., & Carpenter, M. (2018). Open innovation, information, and entrepreneurship within platform ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(3), 369–391.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Santos, F. M. (2002). Knowledge-based view: A new theory of strategy. Handbook of Strategy and Management, 1(1), 139–164.

Elia, S., Giuffrida, M., Mariani, M. M., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Resources and digital export: An RBV perspective on the role of digital technologies and capabilities in cross-border e-commerce. Journal of Business Research, 132, 158–169.

Franke, F., Franke, S., & Riedel, R. (2020). Retrofit concept for textile production. In IFIP International conference on advances in production management systems (pp. 74–82). Springer, Cham.

Gawer, A. (2021). Digital platforms’ boundaries: The interplay of firm scope, platform sides, and digital interfaces. Long Range Planning, 54(5), 102045.

Ghezzi, A., & Cavallo, A. (2020). Agile business model innovation in digital entrepreneurship: Lean startup approaches. Journal of Business Research, 110, 519–537.

Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 109–122.

Hoe, S. L. (2019). Digitalization in practice: The fifth discipline advantage. The Learning Organization, 27(1), 54–64.

Jacobides, M. G., Cennamo, C., & Gawer, A. (2018). Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strategic Management Journal, 39(8), 2255–2276.

Jiménez-Jiménez, D., & Sanz-Valle, R. (2011). Innovation, organizational learning, and performance. Journal of Business Research, 64(4), 408–417.

Kapoor, R., & Agarwal, S. (2017). Sustaining superior performance in business ecosystems: Evidence from application software developers in the iOS and Android smartphone ecosystems. Organization Science, 28(3), 531–551.

Kenney, M., & Zysman, J. (2020). The platform economy: Restructuring the space of capitalist accumulation. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 13(1), 55–76.

Kimmerle, J., Cress, U., & Held, C. (2010). The interplay between individual and collective knowledge: Technologies for organisational learning and knowledge building. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 8(1), 33–44.

King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton University Press.

Klofsten, M., Urbano, D., & Heaton, S. (2021). Managing intrapreneurial capabilities: An overview. Technovation, 99, 102177.

Koch, T., & Windsperger, J. (2017). Seeing through the network: Competitive advantage in the digital economy. Journal of Organization Design, 6(1), 1–30.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383–397.

Kuratko, D.F., Hornsby, J.S., & McKelvie, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial mindset in corporate entrepreneurship: Forms, impediments, and actions for research. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–23.

Kuusisto, M. (2017). Organizational effects of digitalization: A literature review. International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior, 20(3), 341–362.

Lenkenhoff, K., Wilkens, U., Zheng, M., Süße, T., Kuhlenkötter, B., & Ming, X. (2018). Key challenges of digital business ecosystem development and how to cope with them. Procedia Cirp, 73, 167–172.

Leonardi, P., & Treem, J. W. (2020). Behavioral visibility: A new paradigm for organization studies in the age of digitization, digitalization, and datafication. Organization Studies, 41(12), 1601–1625.

Leyden, D.P., & Menter, M. (2022). The impact of knowledge transfer on innovation: Exploring the cross-fertilization of basic and applied research. In Handbook of technology transfer (pp. 25–38). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Leyden, D. P., & Menter, M. (2018). The legacy and promise of Vannevar Bush: Rethinking the model of innovation and the role of public policy. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 27(3), 225–242.

Li, W., Liu, K., Belitski, M., Ghobadian, A., & O’Regan, N. (2016). e-Leadership through strategic alignment: An empirical study of small-and medium-sized enterprises in the digital age. Journal of Information Technology, 31(2), 185–206.

Linneberg, M. S., & Korsgaard, S. (2019). Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research Journal, 19(3), 259–270.

Locke, K., Feldman, M., & Golden-Biddle, K. (2022). Coding practices and iterativity: Beyond templates for analyzing qualitative data. Organizational Research Methods, 25(2), 262–284.

Mariani, M., & Borghi, M. (2019). Industry 4.0: A bibliometric review of its managerial intellectual structure and potential evolution in the service industries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 149, 119752.

Mariani, M. M., & Nambisan, S. (2021). Innovation analytics and digital innovation experimentation: The rise of research-driven online review platforms. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 172, 121009.

Mariani, M. M., & Wamba, S. F. (2020). Exploring how consumer goods companies innovate in the digital age: The role of big data analytics companies. Journal of Business Research, 121, 338–352.

Matt, C., Hess, T., & Benlian, A. (2015). Digital transformation strategies. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 57(5), 339–343.

Mendes, T., Braga, V., Silva, C., & Ratten, V. (2023). Taking a closer look at the regionally clustered firms: How can ambidexterity explain the link between management, entrepreneurship, and innovation in a post-industrialized world? The Journal of Technology Transfer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-022-09991-5

Moore, J. F. (1993). Predators and prey: A new ecology of competition. Harvard Business Review, 71(3), 75–86.

Moore, J. F. (1996). The death of competition: Leadership and strategy in the age of business ecosystems. Harper Paperbacks.

Nambisan, S., & Baron, R. A. (2013). Entrepreneurship in innovation ecosystems: Entrepreneurs’ self-regulatory processes and their implications for new venture success. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 37(5), 1071–1097.

Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029–1055.

Nambisan, S., & Baron, R. A. (2021). On the costs of digital entrepreneurship: Role conflict, stress, and venture performance in digital platform-based ecosystems. Journal of Business Research., 125, 520–532.

Nonaka, I., & Toyama, R. (2003). The knowledge-creating theory revisited: Knowledge creation as a synthesizing process. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1, 2–10.

Penrose, E. T. (2009). The theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford University Press.

Petrovic, V., Pesic, M., Joksimovic, D., & Milosavljevic, A. (2019). Digitalisation in the textile industry – 4.0 industrial revolution in clothing production. In International joint conference on environmental and light industry technologies. November, Budapest.

Pettigrew, A. M. (1995). Longitudinal field research on change. In G. P. Huber & A. H. Van de Ven (Eds.), Longitudinal field research methods (pp. 91–125). Sage Publications.

Senyo, P. K., Liu, K., & Effah, J. (2019). Digital business ecosystem: Literature review and a framework for future research. International Journal of Information Management, 47, 52–64.

Seyedghorban, Z., Samson, D., & Tahernejad, H. (2020). Digitalization opportunities for the procurement function: Pathways to maturity. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(11), 1685–1693.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226.

Steininger, D. M. (2019). Linking information systems and entrepreneurship: A review and agenda for IT-associated and digital entrepreneurship research. Information Systems Journal, 29(2), 363–407.

Stojčić, N. (2021). Collaborative innovation in emerging innovation systems: Evidence from central and eastern Europe. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(2), 531–562.

Urbig, D., Reif, K., Lengsfeld, S., & Procher, V. D. (2021). Promoting or preventing entrepreneurship? Employers’ perceptions of and reactions to employees’ entrepreneurial side jobs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 172, 121032.

Wamba, S. F., Gunasekaran, A., Akter, S., Ren, S. J., Dubey, R., & Childe, S. J. (2017). Big data analytics and firm performance: Effects of dynamic capabilities. Journal of Business Research, 70, 356–365.

Wensli Group. (2015). Wensli Group. Retrieved 28 April, 2022, from http://en.worldsilk.com.cn/content/8114.html

Wensli Group. (2021). IPO prospectus, Retrieved 28 April, 2022, from https://q.stock.sohu.com/newpdf/202146098423.pdf

Wright, M., & Stigliani, I. (2013). Entrepreneurship and growth. International Small Business Journal, 31(1), 3–22.

Yildiz, H. E., Murtic, A., Klofsten, M., Zander, U., & Richtner, A. (2021). Individual and contextual determinants of innovation performance: A micro-foundations perspective. Technovation, 99, 102130.

Yin, R. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage.

Za, S., Spagnoletti, P., & North-Samardzic, A. (2014). Organisational learning as an emerging process: The generative role of digital tools in informal learning practices. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(6), 1023–1035.