Abstract

Purpose: Sustainability is an important priority for CEOs according to a recent Mckinsey (2021) survey. However, despite growing pressure from capital investors, employees and consumers, few organizations are satisfied with the sustainability objectives achieved beyond objectives related to economic savings. The sustainability challenge is even more difficult for organizations when dealing with designing their innovation portfolio strategies since the markets´ demands and competitors´ strategies may contradict organizations’ sustainability objectives and thus jeopardize their continuity. Some researchers argue that a commitment to sustainability in organizations is not so much a matter of managerial practice but rather is rooted in organizational values (Globocnik et al., 2020). Therefore, this research aims to explore what types of organizational values more effectively promote sustainability-oriented innovation in organizations. Using as a conceptual framework the competing values theory (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983), and adding one dimension, risk aversion, we empirically define some clusters of business typologies from which we derive patterns of value profiles. We show how these clusters’ patterns of values relate to the success of a firm’s sustainability-oriented innovation.

Methodology: To make sense of our literature review and ensure managerial relevance, we surveyed 128 senior managers from different industries and countries to understand how their perceived organizational values may impact their firms’ sustainability-oriented innovation success. As a result, we group the studied organizations into four clusters according to the informed organizational values, and we assess how the different clusters are more or less prone to succeed with a sustainability-oriented innovation strategy.

Findings: Our results show that not all organizational values contribute equally to the success of sustainability-oriented innovation in the market. As a theoretical contribution, we advance current knowledge about how organizational values may impact sustainability-oriented innovation success by providing a framework to measure and follow up on the evolution of necessary organizational values to embrace sustainability-oriented innovation within an organization. From a managerial perspective, we advance knowledge on how organizational values should evolve and change to efficiently deliver more sustainability-oriented innovation. In addition, we describe specific values that organizations should measure and track and otherwise establish as an important first step toward implementing sustainability-oriented innovation within them.

Originality: Our research provides original results by expanding current knowledge on organizational values to better understand which values more efficiently promote competitive sustainability-oriented innovation in organizations. We expand the four organizational cultural archetypes of organizational values to develop a more flexible and actionable framework of five dimensions by adding an important dimension to the model, risk aversion. Together, these dimensions generate new insights through a cluster analysis of organizational differences and inform priorities and courses of actions to undertake.

Research limitations and implications: This research is based on self-report surveys and is therefore exposed to the expected limitations of the survey research methodology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to a recent Mckinsey (2021) survey, sustainability is an important priority for CEOs that aims to strategically impact social and environmental issues (Saltzman et al., 2005). However, despite growing pressure from capital investors, employees and consumers, few organizations are satisfied with the sustainability objectives achieved beyond those objectives related to economic savings. To reach the desired sustainability objectives, firms need to work on the intersection of environmental, social and economic goals (Bansal, 2005).

The sustainability challenge is even more difficult for organizations when dealing with designing their innovation portfolio strategies since markets´ demands and competitors´ strategies may contradict organizations’ sustainability objectives, such as when the implementation of sustainability actions will call for price increases that may favor a competitor´s choice (Málovics et al., 2008). However, if firms proceed with a traditional approach to innovation, they may find that their innovative efforts alone fail to solve the challenges of sustainability, e.g., due to an excessive consumption of resources or waste management (Hansen & Grosse-Dunker, 2013; Bos-Brouwers, 2010), therefore making innovation unsustainable (Hart & Milstein, 2003). This makes it necessary for firms to establish some additional criteria for sustainability within the innovation process.

According to Roome (1994) and Martínez-Conesa et al. (2017), when firms aim to contribute to sustainability development, they must create both a sustainability-oriented practice and innovation. Sustainability-oriented innovation (SOI) is the capability of an organization to contribute to sustainable development while simultaneously delivering economic, social, and environmental benefits—the so-called triple bottom line (Hart & Milstein, 2003).

Therefore, the concept of SOI includes several types of innovation in addition to classical product innovations, such as processes, organizational innovation (Rennings, 2000) and business model innovations (Chesbrough, 2007; Hansen et al., 2009; Schaltegger et al., 2012). From this perspective, SOI involves making changes in organizational culture, products, processes or practices to create economic, social and environmental value (Adams et al., 2016).

Internal factors such as traditional or inflexible business models (Carayannis et al., 2015) and an unsuitable internal company culture (Saura et al., 2002a) are major barriers to the successful development of innovation. Some authors have researched the best corporate social responsibility strategy for favoring SOI (Sharma & Vredenburg, 1998; Torugsa et al., 2012; Bocquet et al., 2013). However, other authors argue that a commitment to SOI in organizations is not so much a matter of corporate strategy but is rather rooted in organizational culture (Globocnick et al., 2020; Florea et al., 2013). Stubbs and Cocklin (2008) argue that firms must develop internal structural and cultural capabilities to achieve firm-level sustainability.

Organizational culture is defined as a complex set of values, beliefs, assumptions and symbols that defines how a firm conducts its business (Barney, 1986). The core of organizational culture is shared values, and it describes the ideation aspects of organizational values (Büschgens et al., 2013).

Organizational values enhance firm performance, especially in terms of long-term survival, because they contribute to a long-term vision, which is of utmost importance in establishing an SOI strategy, as they serve as a reference point for decision-making in formulating sustainability strategies (Florea et al., 2013).

The number of values that can be used to describe organizational cultures is theoretically infinite (Denison, 1996); however, managers require an underlying structure to determine which culture should be implemented to foster sustainability-oriented innovation. Competing values theory (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983) has been frequently used as a framework to model organizational culture. Competing values theory posits that culture can be described by three values related to juxtaposed dimensions: control/flexibility, internal/external and means/end dimensions. These dimensions are not mutually exclusive and can exhibit some tensions among them.

These three dimensions are further combined to define four quadrants representing system values, such as human relations, open systems, internal processes and rational goal system values. These system values have been interpreted and operationalized in different ways by several authors in the context of innovation management.

For example, Büschgens et al. (2013) describe in a meta-analysis study which types of cultures are most likely to exist in innovative organizations. Globocnik et al. (2020) investigate how certain cultural archetypes predispose some organizations to perform better in sustainability-related innovation and economic performance. Notably, these studies assume that organizations are clustered into independent, predefined and static culture types, such as clan, adhocracy, hierarchy and market cultures (Globocnik et al., 2020).

Despite the valuable contributions of these studies, by predefining the archetype of organizational cultures to investigate, the authors adopt a practical approach to simplify the complexity of the interactions of the system of values that are not necessarily independent since opposite locations in the quadrants do not denote empirical opposites (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983). Therefore, this static approach to organizational culture presents two limitations. First, organizational value profiles may shift over time to achieve certain ends (Sullivan et al., 2001) or to adapt to technological or environmental changes (Buenger et al., 1996). Second, the paradoxical conclusion of competing values theory is that all dimensions of a values system might be simultaneously important and even positively correlated (Buenger et al., 1996; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983). It is in light of the current organizational culture when managers decide which system values to prioritize and the relative attention that each manager must dedicate to them (Quinn & Mcgrath, 1982).

Third, the heterogeneity of firms might be rooted in goals and values (Chrisman et al., 2012) that serve as reference points for decisions as well as for behaviors (Gehman et al., 2013). Imposing independent and particular clusters of culture may limit understanding of uncovered values and firm performance.

Therefore, this research aims to first overcome previous limitations in the study of the relationship of organizational values and SOI by exploring which types of organizational values more effectively promote SOI. Second, we aim to empirically define some nonpredefined/unsupervised clusters of business typologies with derived patterns of values profiles to showcase how these patterns of cultural values relate to the success of a firm’s sustainability oriented innovation. Third, we aim to measure the market success of SOI as perceived in comparison to competitors, therefore advancing knowledge of the importance of SOI to organizations.

This research makes several theoretical and managerial contributions.

From a theoretical perspective, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to unveil the different unsupervised culture typologies related to SOI’s perceived competitive performance. This is the first study to combine competitive framework dimensions with the risk aversion dimension, which is very relevant to consider in the innovation domain.

From a managerial perspective, our results will help managers understand which values are missing and which values should be required in their organizational cultures to effectively deliver SOI. Therefore, this research will show managers where to prioritize their efforts to build an organizational culture that will drive successful and competitive SOI.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. First, we discuss the competing values framework and its relationship to innovation and sustainability. We then describe our research setting, our methodology for developing our cluster analysis and the resulting firm profiles. Finally, we discuss the study’s outcomes and managerial and theoretical implications and make propositions for future research.

2 Conceptual background

2.1 The competing values Framework for sustainability oriented Innovation

Quinn and Rohrbaugh’s (1983) competing value framework describes system values based on two main dimensions. Each dimension features two pairs of opposing values, flexibility versus control and internal versus external orientation. To these two dimensions is added a third dimension that refers to the preferred processes, called means in the model, and preferred outcomes, called ends. The authors provide a meaningful framework for the ideational aspects of organizational culture in a comprehensive manner, fulfilling the requirement to describe the basic underlying cultural environment of an organization. (Globocnik, 2020).

From the combination of the axes, we find 4 quadrants. The core tenet of the Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983) model is that an organization is effective when it satisfies multiple performance criteria based on the four sets of values.

The first system values refer to open system values (OS). This model emphasizes the need to maintain flexibility and external orientation. It is distinguished by a concern for consistency with a changing external environment. The type of culture with which it is identified is the culture of development, where workers have a preference for goals of growth and the acquisition of resources. Such goals are perfectly aligned with innovation, as invention and innovation can be seen as means to achieve these goals (Quinn & McGrath, 1985).

System values of human relations (HR) emphasize a need to maintain flexibility and an internal orientation. The system embodies the concerns of organizations regarding their employees. The HR value system is expressed by an organization’s concern for its employees and emphasizes positive working relationships (Buenger et al., 1996). The preferred goal of this system value, human resource development, is strongly compatible with the intention to be innovative (Boothby et al., 2010).

System values of rational goals (RG) emphasize the need to maintain control and are based on an external orientation. They correspond to a rational culture concerned with planning and setting goals, following rather formal means of control based on compliance with existing rules and procedures. A failure to accept emerging opportunities and not accepting some flexibility with the given rules can lead to less experimentation and creativity (Mainemelis, 2010).

Finally, a value system of internal processes (IP) emphasizes the need to maintain control and is based on an internal focus. It presents a hierarchical culture with stability being the priority goal. Authors such as Jaworski et al. (1993) positively relate this system to employee satisfaction, as it provides a low level of ambiguity and a sense of security. While stability may satisfy an employee’s desire for security, it can become detrimental to innovation (Büschgens, 2013). Organizational constraints, such as detailed procedures and rules, may decrease organizational creativity (Amabile, 1988; Amabile et al., 1996) and therefore innovation output.

From a theoretical perspective, some authors have established a relationship of these four system values with corporate sustainability (Linnenluecke & Grifths, 2010); however, few studies have empirically measured the impact of these system values on SOI.

SOI includes the integration of ecological and social aspects into products, processes and organizational structures (Klewitz & Hansen, 2014) to avoid or reduce the environmental load and achieve greater benefit in the community (Hellström, 2007; Rennings & Zwick, 2002; Rennings et al., 2006). To contribute to sustainability, innovation is an important means (Hansen et al., 2009; Schaltegger & Wagner, 2011). However, the nature of SOI is complex, so it cannot be assumed from the perspective of innovation in general (De Marchi, 2012). The term “orientation” emphasizes that sustainability is not an end point but rather a direction linked to directional risks, since the direction of the environmental and social impacts of sustainability innovations is highly uncertain, particularly in the long term (Hansen & Grosse-Dunker, 2013). Through SOI, companies can build more sustainable products, processes and practices that benefit a firm and society (Adams et al., 2012) with a forward-looking perspective (Charter et al., 2017) and usually go beyond incremental product and process innovations due to the systemic and radical character of sustainable innovations (Boons et al., 2013).

For their part, Adams et al. (2016) elaborated a framework to examine innovation activities for sustainability suggesting that SOI is an organizational problem because its implementation implies making premeditated changes in organizations; in their philosophies and values; as well as in their products, processes or business practices that involve achieving, creating and performing social and environmental value, in addition to economic returns.

Despite a proliferation of SOI conceptualizations and recommendations, few studies have actually measured the impact of organizational values on SOI performance. The few studies dealing with this research objective, despite offering valuable insights, provide controversial results in terms of the impact of predefined cultural archetypes on sustainability-related innovation. Globocnik et al. (2020) aimed to explain the differences in sustainability-related innovation performance among firms and their relationship with the economic value of innovation. The authors’ results show that clan cultures have a negative influence on sustainability-related innovation, diverging from the results of Reyes-Santiago et al. (2017), who did not find significant relationships between clan culture and the environmental innovation-related performance measure.

None of these studies assess SOI success in terms of perceived market performance, nor do they allow the characterization of a company’s culture to go beyond archetypes that, given the heterogeneity of industries and external factors such as market turbulence, regulations and concentration, may affect the configuration of organizational values.

In this study, we use the operationalization of the competing values system proposed by Buenger et al. (1996) to explore how these system values relate to SOI performance. For this purpose, we have included a fifth dimension to the model, risk aversion (RA) values, as it has been incorporated into previous studies of innovation management and culture (Tsur et al., 1990; Meroño-Cerdán et al., 2018) given the important influence RA has in delivering innovation in firms.

Under this conceptual framework, we aim to explore how these five systems of values are combined in different firms and which clusters of system value combinations provide greater effectiveness in delivering successful SOI in the marketplace.

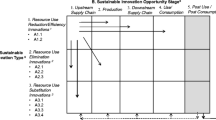

We describe the framework for our empirical research in Fig. 1.

3 Method and sample

To measure which organizational values better define SOI, we consider as a basis the competing values framework of Quinn and Rohrbaugh’s (1983) model. Therefore, we consider the four system value dimensions of human relations (HR), rational goals (RG), open systems (OS), and internal processes (IP) while adapting the measures of these dimensions from the operationalization and empirical research by Buenger et al. (1996). We select the items found to be significant in their study, and we add an additional fifth dimension extracted from the literature on innovation, the construct of risk aversion (RA), which has been shown to be an important part of company culture as an antecedent of successful innovation in firms (Tsur et al., 1990; Meroño-Cerdán et al., 2018).

We measure SOI success as the perceived competitive performance of SOI efforts in the market: below competitors, similar to competitors, and above competitors.

In Table 1, we describe in detail the items included in each of the five dimensions and their sources.

We collect information through a survey targeted at international managers (Buenger et al., 1996; Globocnik et al., 2020) who have been involved in at least one innovation project in the last three years. Given the specificities of our target, we use a convenience sample for this purpose by extending the survey through the use of professional association databases and snowball sampling.

The questionnaire was in English and was launched from October 2021 to November 2021. A total of 195 questionnaires were received, but as with previous researchers, we used an exclusion criterion relating to involvement in innovative business projects (Saura et al., 2022b), resulting in 128 valid surveys in accordance with the required sample profile. In Table 2, we describe the sample in detail according to each participant’s level of seniority (number of years), firm sector (industrial, manufacturer, service, and others), headquarters continent (the Americas, Asia and Africa, Eastern Europe, Western Europe and Oceania) and company size (revenues and number of employees).

In terms of the instrument for analysis and to uncover the different underlying dimensions of the value systems, we performed an exploratory factor analysis, that of principal component analysis (PCA). Next, we performed a cluster analysis to extract companies with similar value profile patterns to understand how the dimensions of the system values relate to SOI’s perceived success.

3.1 Survey Design

The questionnaire was distributed in three different sections. In the first section, we developed a 24-item instrument from which the five dimensions were derived. The five dimensions were measured through Likert (1–5) scales and were adapted from the previous literature. All the items and sources are described in Table 1. The second section of the survey was related to understanding the perceived success of sustainability-oriented innovation in firms. We use a three-item scale to understand whether the managers perceived the SOI success of their firm to be below, similar, or above that of the competition (Kristiansen & Ritala, 2018; Zheng et al., 2017). Finally, in the third section, we collect descriptive information related to firms, such as the country of origin, revenue levels, the number of employees, subsidiaries and headquarters, as these are variables that might influence the adoption of sustainability-oriented innovation (Abbas et al., 2020, Globocnik et al., 2020).

4 Results

Below, we describe the results obtained from the two methods used in our model: exploratory factor analysis and cluster analysis.

4.1 Exploratory factor analysis

First, we checked the quality and appropriateness of the dataset to conduct a principal component analysis (PCA), which was evaluated by assessing the degree of interrelatedness (Hair et al., 2006). We expect the factorial model to be adequate if the elements on the diagonal of the anti-image correlation matrix have a value close to 1.

Second, we conduct a Kaiser Meyer Olkin test (KMO = 0.884) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (sig = 0.000). Both indicate that the data matrix has sufficient correlations to justify the application of a PCA. Therefore, we expect the analysis to yield distinct and reliable factors (Field, 2009). Since the matrix determinant is also 0, performing an exploratory factor analysis is an appropriate technique.

Based on orthogonal factor rotation, the PCA generated a five-factor model accounting for 69.17% of the total variance. From orthogonal rotation (varimax), the factor solution resulted in noncorrelating factors (Hair et al., 2006).

The number of factors is determined based on the Kaiser criterion, which considers only factors with an eigenvalue of greater than 1 to be significant. We considered variables belonging to a specific factor when their factor loadings were valued at > 0.50; thus, we eliminated four items. Five factors were obtained with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients above the overall threshold value of 0.60 for exploratory factor analysis (Hair et al., 2006). Each indicator was placed in the factor in which its loadings were higher. However, to ensure consistency with the literature and given that their loads meet the established condition (> 0.4), two indicators (provide each individual with an opportunity to grow and develop high morale) were placed under the “human relations” dimension where they belong from a theoretical perspective. The results of the items and factors are shown in Table 3.

4.2 Cluster analysis: identification of management groups

We use a cluster analysis to group companies that share similar organizational values. This approach is ideal for classifying observations into similar groups and developing a taxonomy (Hair et al., 1998; Ketchen & Shook, 1996).

Lehman (1979) suggested that the number of groups should be between n/30 and n/60, where n represents the sample size. Therefore, the number of clusters in our data must be between 2 and 4 (128/60 and 128/30). We conduct a hierarchical cluster analysis to define the appropriate number of clusters because from this analysis, we obtain a unique set of nested categories or a sequential pairing of variables. For the clustering, we use the Ward method, one of the most used methods in this type of social science research. We obtain a hierarchical dendrogram, a visual representation of the steps of the hierarchical cluster analysis, and an agglomeration schedule table showing the combined clusters. We measure the interval according to the squared Euclidean distinction. We consider the values 10 and 15 for the combination of rescaled distance clusters. Thus, we conclude that 4 clusters represent the best solution for our study (n1 = 35 n2 = 26 n3 = 54 n4 = 13).

To analyze whether the differences between the clusters are significant, we first check the Shapiro‒Wilk statistic (gl < 50). Since Levene’s statistic is significant as well (> 0.05), we confirm that homogeneity of variances exists and proceed to an analysis of variance (ANOVA), finding a high level of significance (0.000).

Finally, we conclude with a post hoc analysis of the Tukey statistic that confirms the presence of differences between the clusters in all factors.

In Table 4, we show the standardized values of the clusters based on the dimensions, which represent the number of standard deviations each factor is away from its mean (the mean for the entire sample is equal to 0).

We observe that Cluster 1 is characterized by being below the average in practically all of the factors, except for rational goal system values (RG), which are slightly above the average. Cluster 2 is distinguished by reaching the highest value in Factor 1 human relations system values (HR) and Factor 4 open system values (OS). Cluster 3 is distinguished by significantly exceeding the mean in Factor 3 risk aversion (RA) and 5 rational goal system values (RG). Finally, Cluster 4 is differentiated by Factor 2 internal processes (IP), representing the cluster that shows the greatest difference with respect to the mean.

The F values confirm the existence of significant differences among the clusters in all factors (p value < 0.001). We measured the sizes of the effects of the factors through eta squared, and all of them were between good and acceptable.

We visually show the four cluster profiles in Fig. 2. From these figures, we can compare the differences between the 4 clusters given the five factors identified as well as the comparison to the overall average.

Table 5 shows a description of each cluster. In terms of the characterization of the clusters, we observe that Cluster 1 shows a large number of firms (45%) perceiving their SOI performance as below competitors. In contrast, the majority of firms (55%) that declare an SOI performance level above competition are located in Cluster 3, followed by those in Cluster 2 (25%). American firms are skewed toward Cluster 1 (44%), while Cluster 3 includes the majority of Western European firms (42%) and industrial firms. Cluster 3 also includes firms that adopt a more holistic approach to sustainability, while firms included in Cluster 1 declare a more limited approach to sustainability.

5 Discussion

This research aimed to explore first what types of organizational values more effectively promote SOI perceived market success in organizations. Second, we aimed to empirically define some clusters of business typologies with derived patterns of value profiles to showcase how these patterns of cultural values relate to the success of a firm’s SOI.

Building on the competing values organizational framework and adding a fifth dimension of risk aversion, we find five factors to derive 4 typologies of clusters that differ in their organizational values and SOI perceived market success.

Firms in Cluster 1 can be described as adopting a “Rational values-driven Culture.” The companies that are part of this cluster (n1 = 35) are defined as organizations that are not very open to the environment (OS), that have a risk tolerance (RA) level below the average, and that stand out for making rational decisions, obtaining high value from rational goals (RG) above the average. They are traditional companies capable of changing their operating routines only when necessary to compete in the market, since they feel capable of effectively responding to crises or emergencies when they arise and adapt quickly to changes in the market or the environment or to new demands. They also exhibit limited flexibility in adopting new processes, which explains why they make changes only when necessary.

These companies are characterized by perceiving a low degree of success of their SOI projects when compared to their competitors. This perception may be because a significant percentage of these companies belong to the service sector, where innovations are more easily copied and thus considered noninnovative activities (Morrar, 2014). Although this approach has been surpassed, there is still an organizational culture that links innovation to manufacturing sectors (Gallouj & Savona, 2009). From the firm descriptions, a majority of the companies included in this cluster are based in North America, South America and Australia, and they can be classified as large companies.

It is interesting to point out a significant percentage of companies in this cluster whose managers describe their organizational approach to sustainability as “in compliance with regulations” and with limited action on sustainability beyond such compliance. It is important to note that this indicator for a company’s sustainability measurement is at the lowest level according to the proposed Likert scale. This may explain the lesser success of sustainability-oriented innovation projects, as they will not represent a competitive advantage since they only match compliance in the industry that every company in the industry will exhibit as well.

Firms in Cluster 2 can be described as adopting a “Developmental Values-driven Culture.” It is a cluster made up of companies that significantly outperform the average of the rest of the cluster in the human relations system values (HR) and open systems (OS) dimensions. Risk tolerance (RA) is similar to the average. We observe that companies that are part of this cluster seek to learn from their workers, develop supportive work relationships, generate team spirit with high morale, provide each individual with the opportunity to grow and opt not only for achieving financial performance but also social impact. In addition, this concern for the organizational values of HR aligns with a commitment to the OS dimension. The managers of companies that are part of this cluster care about incorporating the latest technologies as soon as possible; encourage workers to find innovative ways of doing things; emphasize cutting-edge technology; and value workers’ contributions in developing new ideas, inventions or methods.

Therefore, openness and human relations seem to drive the SOI of this cluster significantly above their competitors.

Firms in Cluster 3 can be described as having a “Balanced Organizational Culture.” Regarding the five dimensions studied, the companies belonging to this cluster obtain scores slightly above the average in all values dimensions, thus being the “most balanced cluster.” This cluster is made up of companies that perceive themselves as performing the same as or better than the competition in terms of the success of their sustainability innovation. This result might be because the majority of companies in this cluster belong to the industrial and manufacturing sector, rendering them able to generate R&D patents as opposed to other service industries. It is important to highlight that the majority of companies that declare high levels of concern for and a more holistic approach to sustainability belong to this cluster and are located in Europe. By company size, they are moderately sized with up to 50 mm $ in revenue and fewer than 100 employees, a company size that might be favorable for overcoming the inertia that larger organizations typically encounter, allowing them to be flexible and competitive in the markets in which they operate. The respondents declared their companies to be ahead in sustainability compliance and cost reduction relative to their competitors. They report that environmental and social factors contribute to market success and embed these factors within their core business strategies.

Firms in Cluster 4 can be described as adopting a “Hierarchical Organizational Culture.” According to the results obtained, managers of these companies define their companies a very oriented toward internal processes (IP) to maintain a high level of productivity, to do work efficiently, to achieve planning even beforehand, to exercise strong control over people and to organize work activities in a predictable way. This cluster is made up of companies that do not exhibit a strong characterization in their descriptions. Most of the firms that perceive their SOI performance as below that of competitors are in this cluster, perhaps due to the strong internal focus signaled by the IP values dimension.

6 Conclusion

Our research shows the importance of organizational values to SOI market success, therefore suggesting the importance of the organizational culture to enjoying superior performance when dealing with SOI objectives.

This research makes several theoretical and managerial contributions.

From a theoretical perspective, we contribute to the theory responding to calls to advance current knowledge and organizational learning about SOI (Adams et al., 2012; Siebenhüner & Arnold, 2007; Klewitz & Hansen, 2014).

We shed light on how organizational values may impact sustainability-oriented innovation success. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to unveil the different unsupervised culture typologies that are related to SOI’s perceived competitive performance.

By doing so, we expand current knowledge on organizational values to better understand which values more efficiently promote sustainability-oriented innovation success in organizations. Moreover, under the innovation context of this study, we propose adding a fifth dimension independent from the other four, risk aversion, which is important in the context of organizational culture and innovation.

As a result, we propose a more flexible and actionable framework based on the competing values framework to overcome the rigidity of current organizational cultural archetypes, as organizational value systems might not be classified solely into one of the four system values. For example, in an organization, efficiency might be the dominant value pursued, but the organization might also seek to achieve a high level of flexibility (Buenger et al., 1996).

From a managerial perspective, our results can help inform managers understand what values are missing and what values should be required in their organizational cultures to effectively generate SOI that will deliver a competitive advantage in the marketplace.

To do so, first, we describe specific values that organizations should measure and track as an important first step to implementing SOI within them, and we provide an empirical framework to measure and follow up on the evolution of these values. Second, our results show that not all organizational values contribute equally to SOI as a competitive advantage, therefore suggesting a need for managers to evaluate the profiles of their firms and take action to developing missing values.

Last, this research shows how managers can prioritize their efforts to build an organizational culture that will drive successful and competitive SOI. Overall, our results suggest the importance of a proactive sustainability-oriented culture as a precursor of sustainability innovation success, as compliance seems to not deliver the competitive advantage that organizations seem to expect from innovation.

7 Limitations and future research lines

This research is not exempt from limitations driven by the use of surveys and convenience sampling. Future research should adopt a confirmatory research design by researching a sample with quotas predefined by size and industry type to further advance our exploratory results. Future research should investigate how a sustainability-oriented culture is defined and its influence on sustainability-oriented innovation success, as our exploratory results suggest an interesting relationship between them.

References

Abbas, J., Zhang, Q., Hussain, I., Akram, S., Afaq, A., & Shad, M. A. (2020). Sustainable innovation in small medium enterprises: the impact of knowledge management on organizational innovation through a mediation analysis by using SEM approach. Sustainability, 12(6), 2407.

Adams, R., Bessant, J., Jeanrenaud, S., Overy, P., & Denyer, D. (2012). Innovating for sustainability: a systematic review of the body of knowledge. Network for Business Sustainability.

Adams, R., Jeanrenaud, S., Bessant, J., Denyer, D., & Overy, P. (2016). Sustainability-oriented innovation: A systematic review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(2), 180–205.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of management journal, 39(5), 1154–1184.

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in organizational behavior, 10(1), 123–167.

Bansal, P. (2005). Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainability development. Strategic management journal, 26(3), 197–218.

Barney, J. B. (1986). Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy. Management science, 32(10), 1231–1241.

Bocquet, R., Le Bas, C., Mothe, C., & Poussing, N. (2013). Are firms with different CSR profiles equally innovative? Empirical analysis with survey data. European Management Journal, 31(6), 642–654.

Boons, F., Montalvo, C., Quist, J., & Wagner, M. (2013). Sustainable innovation, business models and economic performance: an overview. Journal of cleaner production, 45, 1–8.

Boothby, D., Dufour, A., & Tang, J. (2010). Technology adoption, training and productivity performance. Research Policy, 39(5), 650–661.

Bos-Brouwers, H. E. J. (2010). Corporate sustainability and innovation in SMEs: Evidence of themes and activities in practice. Business strategy and the environment, 19(7), 417–435.

Buenger, V., Daft, R. L., Conlon, E. J., & Austin, J. (1996). Competing values in organizations: Contextual influences and structural consequences. Organization Science, 7(5), 557–576.

Büschgens, T., Bausch, A., & Balkin, D. B. (2013). Organizational culture and innovation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of product innovation management, 30(4), 763–781.

Carayannis, E. G., Sindakis, S., & Walter, C. (2015). Business model innovation as lever of organizational sustainability. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(1), 85–104.

Charter, M., Gray, C., Clark, T., & Woolman, T. (2017). The role of business in realising sustainable consumption and production. System Innovation for Sustainability 1 (pp. 56–79). Routledge.

Chesbrough, H. (2007). Business model innovation: it’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy & leadership, 35(6), 12–17.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Pearson, A. W., & Barnett, T. (2012). Family involvement, family influence, and family–centered non–economic goals in small firms. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 36(2), 267–293.

De Marchi, V. (2012). Environmental innovation and R&D cooperation: Empirical evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Research policy, 41(3), 614–623.

Denison, D. R. (1996). What is the difference between organizational culture and organizational climate? A native’s point of view on a decade of paradigm wars. Academy of management review, 21(3), 619–654.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS: Introducing Statistical Method (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Florea, L., Cheung, Y. H., & Herndon, N. C. (2013). For all good reasons: Role of values in organizational sustainability. Journal of business ethics, 114(3), 393–408.

Gallouj, F., & Savona, M. (2009). Innovation in Services: A Review of the Debate and a Research Agenda. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 19(2), 149–172.

Gehman, J., Trevino, L. K., & Garud, R. (2013). Values work: A process study of the emergence and performance of organizational values practices. Academy of management Journal, 56(1), 84–112.

Globocnik, D., Faullant, R., & Parastuty, Z. (2020). Bridging strategic planning and business model management–A formal control framework to manage business model portfolios and dynamics. European Management Journal, 38(2), 231–243.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Badin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Ronald, L. T. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Hansen, E. G., & Grosse-Dunker, F. (2013). Sustainability-Oriented Innovation. In S. O. Idowu, N. Capaldi, L. Zu, & A. Das Gupta (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility (1( vol., pp. 2407–2417). Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag.

Hansen, E. G., Grosse-Dunker, F., & Reichwald, R. (2009). Sustainability innovation cube—a framework to evaluate sustainability-oriented innovations. International Journal of Innovation Management, 13(04), 683–713.

Hart, S. L., & Milstein, M. B. (2003). Creating sustainable value. Academy of Management Perspectives, 17(2), 56–67.

Hellström, T. (2007). Dimensions of environmentally sustainable innovation: the structure of eco-innovation concepts. Sustainable development, 15(3), 148–159.

Jaworski, B. J., Stathakopoulos, V., & Krishnan, H. S. (1993). Control combinations in marketing: conceptual framework and empirical evidence. Journal of marketing, 57(1), 57–69.

Ketchen, D. J., & Shook, C. L. (1996). The application of cluster analysis in strategic management research: An analysis and critique. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 441–459.

Klewitz, J., & Hansen, E. G. (2014). Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: a systematic review. Journal of cleaner production, 65, 57–75.

Kristiansen, J. N., & Ritala, P. (2018). “Measuring radical innovation project success: typical metrics don’t work”. Journal of Business Strategy, 39 No(4), 34–41.

Lehman, D. R. (1979). Market research and analysis. Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Linnenluecke, M. K., & Griffiths, A. (2010). Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. Journal of world business, 45(4), 357–366.

Mainemelis, C. (2010). Stealing fire: Creative deviance in the evolution of new ideas. Academy of management review, 35(4), 558–578.

Málovics, G., Csigéné, N. N., & Kraus, S. (2008). The role of corporate social responsibility in strong sustainability. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(3), 907–918.

Martínez-Conesa, I., Soto-Acosta, P., & Palacios-Manzano, M. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and its effect on innovation and firm performance: An empirical research in SMEs. Journal of Cleaner Production, 142, 2374–2383.

McKinsey (2021). How companies capture the value of sustainability: Survey findings. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/ourinsights/how-companies-capture-the-value-of-sustainability-survey-findings.

Meroño-Cerdán, A. L., López-Nicolás, C., & Molina-Castillo, F. J. (2018). Risk aversion, innovation and performance in family firms. Economics of Innovation and new technology, 27(2), 189–203.

Morrar, R. (2014). Innovation in services: A literature review.Technology Innovation Management Review, 4(4).

Quinn, R. E., & McGrath, M. R. (1982). Moving beyond the single-solution perspective: The competing values approach as a diagnostic tool. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 18(4), 463–472.

Quinn, R. E., & McGrath, M. R. (1985). The transformation of organizational cultures: A competing values perspective.

Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management science, 29(3), 363–377.

Rennings, K., & Zwick, T. (2002). Employment impact of cleaner production on the firm level: Empirical evidence from a survey in five European countries. International Journal of Innovation Management, 6(03), 319–342.

Rennings, K., Ziegler, A., Ankele, K., & Hoffmann, E. (2006). The influence of different characteristics of the EU environmental management and auditing scheme on technical environmental innovations and economic performance. Ecological Economics, 57(1), 45–59.

Rennings, K. (2000). Redefining innovation—eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics. Ecological economics, 32(2), 319–332.

Reyes-Santiago, M. D. R., & Díaz-Pichardo, R. (2017). “Eco-innovation and organizational culture in the hotel industry.“ International Journal of Hospitality Management 65 (2017): 71–80.

Roome, N. (1994). Business strategy, R&D management and environmental imperatives. R&D Management, 24(1), 065–082.

Saltzman, O., Ionescue-Somers, A., & Steger, U. (2005). The business case for corporate sustainability: literature review and research option. European Management Journal, 23, 2–36.

Saura, J. R., Palacios-Marqués, D., & Ribeiro-Soriano, D. (2022a). Exploring the boundaries of open innovation: Evidence from social media mining.Technovation,102447.

Saura, J. R., Ribeiro-Soriano, D., & Palacios-Marqués, D. (2022b). Adopting digital reservation systems to enable circular economy in entrepreneurship. Management Decision. (ahead-of-print).

Schaltegger, S., & Wagner, M. (2011). Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Business strategy and the environment, 20(4), 222–237.

Schaltegger, S., Lüdeke-Freund, F., & Hansen, E. G. (2012). Business cases for sustainability: the role of business model innovation for corporate sustainability. International journal of innovation and sustainable development, 6(2), 95–119.

Sharma, S., & Vredenburg, H. (1998). Proactive corporate environmental strategy and the development of competitively valuable organizational capabilities. Strategic management journal, 19(8), 729–753.

Siebenhüner, B., & Arnold, M. (2007). Organizational learning to manage sustainable development. Business strategy and the environment, 16(5), 339–353.

Stubbs, W., & Cocklin, C. (2008). Conceptualizing a “sustainability business model”. Organization & environment, 21(2), 103–127.

Sullivan, W., Sullivan, R., & Buffton, B. (2001). Aligning individual and organisational values to support change. Journal of Change Management, 2(3), 247–254.

Torugsa, N. A., O’Donohue, W., & Hecker, R. (2012). Capabilities, proactive CSR and financial performance in SMEs: Empirical evidence from an Australian manufacturing industry sector. Journal of business ethics, 109(4), 483–500.

Tsur, Y., Sternberg, M., & Hochman, E. (1990). Dynamic modelling of innovation process adoption with risk aversion and learning. Oxford Economic Papers, 42(2), 336–355.

Zheng, Q., Guo, W., An, W., Wang, L., & Liang, R. (2017). Factors facilitating user projects success in co-innovation communities. Kybernetes, 47(4), 656–671.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This research has been co-funded by the Erasmus + program of the European Union. IMPACT Project Number : 621672-EPP-1-2020-1-DE-EPPKA2-KA

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rubio-Andrés, M., Abril, C. Sustainability oriented innovation and organizational values: a cluster analysis. J Technol Transf 49, 1–18 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-022-09979-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-022-09979-1